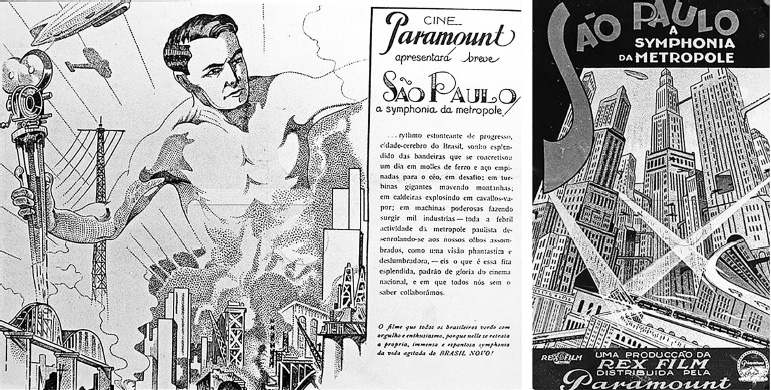

In 1929, a Paramount advertisement proudly announced São Paulo: Sinfonia da Metrópole in several local newspapers:

Paramount will shortly present the film São Paulo: The Symphony of the Metropolis … dazzling rhythm of progress, city brain of Brazil, splendid dream of the exploring expeditions that materialized one day in molds of iron and steel pitched into the air, in challenge; in giant turbines moving mountains; in boilers exploding in horsepower; in powerful machines making a thousand industries emerge—all the feverish activity of the Paulista metropolis unfolding before our astonished eyes, as a fantastic and fascinating vision. In short, this is a splendid movie, pillar of glory of the national cinema, in which we all cooperate, without knowing it.

The image accompanying this exalted discourse, shaped in a deliberate aesthetic of the sublime, left no room for doubt: a giant, who brandishes in his hand nothing less than a movie camera, makes room between steel viaducts, skyscrapers, and watch towers; above him, just an airplane and a zeppelin. The image summarizes all the desires present in this film portraying the city of São Paulo as a thriving metropolis in line with the latest technological innovations, the cinema among them. The film shows all the forces of progress, which, for a long time, would feed the self-image of São Paulo that experienced a spurt of growth and industrialization at that time. The directors and screenwriters of the film, Adalberto Kemeny and Rodolpho Rex Lustig, both Hungarian immigrants, introduced a new cinematic language in São Paulo, based on montage, unexpected camera movements, and the use of people in the streets as protagonists. They succeeded in overcoming the then current technical limitations, obtaining the necessary resources, finding film stock and equipment for filming and lighting to compete with the cinematic models of the day.1

In the newspaper O Estado de São Paulo the synopsis of the film was presented as follows:

Are you proud of being a “Paulista”? São Paulo: Sinfonia da Metrópole is the soul of the city that you built with your work, singing along the marvelous rhythm of the most formidable progress! The romance of the city! The daily toil of the great anonymous masses caught during precious moments by a camera lens, always cleverly hidden from the eyes of the general public. It is an almost fantastic vision that unfolds before our eyes like a dream, sometimes joyful, sometimes sad, but always enjoyable because it shows the city that we build for our pride and glory and as an example of the new Brazil.2

During the 1920s and 1930s, major Brazilian cities underwent an accelerated process of urbanization. The wealth brought by coffee export had a definitive impact on São Paulo, which was transformed by the construction of new neighborhoods and avenues, an expansion of its electricity system, and the development of an urban transportation network. In the 1920s, inhabitants of remote neighborhoods could for the first time reach the city center by means of tram and omnibus. Venues of recreation and conviviality multiplied, with cafés, restaurants, and cinemas as tokens of a new way of life and new patterns of consumption. These innovations had a permanent impact on the perception of the inhabitants, which was also affected by several newly constructed iconic landmarks such as the iron Santa Efigênia viaduct, which was imported from Belgium in its entirety, and the 1929 Martinelli building, the city’s first skyscraper. Originated as a village founded in 1554 by Jesuit priests and remaining a small fortified town up to the late nineteenth century, São Paulo developed into a metropolis with 550,000 inhabitants in 1920. In 1929, when the film was made, it counted just over one million. Moreover,in 1920, statistics recorded 1,875 new constructions that evolved to 3,922 in 1930. Construction was at the rate of one dwelling per hour. The press enthusiastically stated that “São Paulo was the fastest growing city in the world.”3 Technical innovations and the euphoria of the years after World War I contributed to the perception of a growing city. The word “modern” was amply used in newspaper chronicles and “advertisements and signs scattered throughout various media” spread the news “about subjects ranging from sports activities to medical advances. Everything should be modern to be well rated.”4

According to historian Nicolau Sevcenko,

The New World, represented by São Paulo, where the first white man mixed with an Indian, whose descendants in their turn crossed with black people, and where new generations now consort with the refugees from a troubled and convulsed Europe, is the new promised land where they will raise the solid towers of a new architecture of a future society, an inverted Babel, a Babel which unites.5

Since the last decades of the nineteenth century, the new metropolis that measured itself with Buenos Aires as well as Rio de Janeiro, was the destination of several immigration waves, including Italian, Spanish, German, and later Japanese, Syrian-Lebanese, and Eastern-European immigrants. A gulf of national optimism conquered the country that presented itself to European immigrants as an exotic land, chaotic but full of possibilities for achievement and enrichment. At the same time, artists and wealthy families in Brazil discovered Europe. During the first two decades of the twentieth century, Brazil received more than one million immigrants and an economy based on coffee monoculture turned São Paulo into an international center. The state of São Paulo attracted farm hands (Italians, Japanese), but the city itself was the focus of a great wave of immigrants who came to work in the factories and in newly emerging urban professions, among which those related to industrial image making such as photography, photo editing, and photo journalism. Photo clubs and ciné-clubs emerged. In this context, cinema became a language capable of communicating these changes and cinema theaters became important places to meet and socialize. In 1929, the city had about sixty film theaters.6 Although Hollywood had secured its share in the national cinemas, the audience was also interested in the European avant-garde.

São Paulo: Sinfonia da Metrópole was released on 6 September 1929 at the Paramount theater in São Paulo, where it was screened until 8 September. Then it toured to several other local theaters, such as the Cine São Bento, Marconi, Cambuci, Coliseu, Santa Helena, Paraíso, Espéria, São Pedro, Central, Olímpia, and Moderno. In the beginning of 1930, the film was shown in Curitiba, in the south of the country, and one year after its release it was screened in Manaus, in the far north state of Amazonas. On the opening night, the orchestra of the Paramount theater, then considered the best in town, performed a score composed for the film “in the fashion of the synchronizations of the large American orchestras,” as the newspaper A Folha de Manhã announced.7 Paramount made a series of agreements to show Brazilian films together with films in English, thus overcoming the initial resistance of the Brazilian public to movies spoken in English. In the early 1930s, the film, retitled São Paulo 24 horas, was re-released with a soundtrack comprising music by Gaó Gurgel and a sonography by Lamartine Fagundes. Apparently, some parts were shot again for this new version.

Although Kemeny and Lustig shared directional credits, it is generally assumed that Rodolpho Rex Lustig (1901–70) directed the film while Adalberto Kemeny (1901–69) acted as scriptwriter and cameraman. The intertitles were designed by João Quadros. Little is known about the directors. Born in Budapest, Adalberto Kemeny started his professional life as a laboratory technician in the Hungarian branch of Pathé in the late 1910s. He and his fellow countryman Lustig became professional partners, producing small advertising films. In 1920, they moved to Berlin, where they reportedly worked for UFA. In 1922, at the invitation of director Armando Pamplona of the Independência-Omnia-Film company, Kemeny came to Brazil for the centenary celebrations of the country’s independence. Four years later, Lustig joined him, and in 1928 they were in the position to buy Independência-Omnia, transforming it into Rex Filme.8 After 1929’s São Paulo City Symphony, Kemeny realized six more films and participated in other companies such as Rossi-Rex Film and even in the creation of the Vera Cruz Cinematographic Company, which would become the most important film studio of São Paulo in the early 1950s.

In an interview, Kemeny flatly denied he was inspired by Ruttman’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927).9 How much truth this statement holds cannot be verified. Although the phenomenon of the city symphony was a widespread one, it is striking that no similar films of any other large city in Latin America is known. As Eduardo Morettin has noted, in the first decades of the twentieth century, so-called “national documentaries” had developed in Brazil, which were dedicated to civic events and monumental spaces as well as carnival celebrations in the streets.10 In addition, since the beginning of the century, Brazilian cinema had documented remote places in the jungle and their indigenous populations such as the films made from 1912 onwards by the Photographic and Cinematographic Service of the Rondon Commission.11 Other documentaries had tried to describe everyday life in certain cities, including Walfredo Rodrigues’s 1926 film on the carnival of Pernambuco and Paraíba (O Carnaval paraibano e pernambucano) and the film Sob o céu nordestino on the landscapes and people of the state of Paraíba. Sponsored by the state government, Italian immigrant Igino Bonfiglioli produced the feature-length film Minas Antiga (1927–8) in Minas Gerais. In the Amazon region, feature films and documentaries focused on the production of rubber and the Amazon River. In the far-south state of Rio Grande do Sul, several documentaries dealt with German traditions cultivated among immigrants and their descendants. In the late 1920s, however, these regional cycles were replaced by films focusing on the axis connecting Rio de Janeiro with São Paulo. Given this perspective, the São Paulo city symphony had some predecessors, such as 50 Anos da Cidade de Cataguases (1927) and Sinfonia de Cataguases (1928) by leading filmmaker Humberto Mauro, and Carnaval pernambucano (1926) by Edson Chagas. In 1929, João Batista Groff made in Curitiba the films Cidade de Morretes and Cidade de Paranaguá while José Julianelli, an Italian who had settled in Santa Catarina, directed O progresso de Blumenau (1926).12

Moreover, as Rubens Machado Junior has demonstrated, the evocation of a metropolis in the manner of New York or Berlin was also present in fiction films set in São Paulo, such as Exemplo Regenerador (1919) and Fragmentos da Vida (1929), both directed by José Medina.13 Released a month before Kemeny and Lustig’s São Paulo city symphony, Fragmentos da Vida tells the story of a dying father who asks his son to be honest and hardworking—a plea he does not answer, living a licentious life in the big city and ending in a penitentiary. Likewise, Antônio Tibiriçá’s Vício e Beleza (1926) contrasts the life of a medical student and amateur swimmer and athlete with that of another young man living in bars and cabarets. Of moralizing content, the film warns against drug use and sexually transmitted diseases, emphasizing the dangers of the metropolis.

Even with all these antecedents, São Paulo: Sinfonia da Metrópole stands out for its originality, capturing the frenzy of the metropolis and its inhabitants and evoking the excitement of modern and industrial life. The film unfolds with a plot that sometimes returns on its steps, or repeats itself. In general, it seeks to describe urban life in the span of a single day. The film opens with the silence of dawn, some scenes showing the city still asleep. Then, the city awakens, indicated by a shifting tram and a passerby in the background. The pace gradually begins to increase, showing the distribution of newspapers, a greengrocer passing, and men heading for work.

The following scenes show workers punching the clock at the entry of “factories, foundries, and a thousand industries,” as an intertitle announces, as well as machines that start to work, the awakening in distant neighborhoods, and children going to school. From the moment the city is awake and the trade in the streets and business in the banks come to life, the camera embarks on daring movements by showing people from above. In addition, the film highlights the coffee trade (also known as “the green gold”), considered the driving force of the city’s wealth. When means of communication (telephone, telegraph) enter the scene, Kemeny and Lustig start using juxtapositions of images, through montage, split screens, and multiple-exposure shots, attempting to express the simultaneity of events. This strategy is repeated in several other moments, particularly in the scenes depicting movements of cars, evoking the multitude, speed, and simultaneity of motions and the cacophony of the city.

São Paulo: Sinfonia da Metrópole is surely a documentary with scenes shot on the streets dominating the narrative, but it re-designs its raw footage in a completely subjective way. It is marked by a “poetic mode,” taking its cue from the modernist avant-garde, often replacing classical continuity editing by an assembly of free associations of temporal rhythms and spatial juxtapositions.14 Moreover, the film is somewhat heterogeneous and also includes sequences of a different type of nature. First, there are the “staged” scenes (small anecdotes) that add a more personal touch to the film, but which disappear from the middle onwards. These scenes are, however, part of a narrative that suggests that they were recorded at random: a child reproaching another child for throwing fruit on the ground, two women chatting at the window, filmed from inside the house of one of them, et cetera. The second deviation from the main narrative consists of educational sequences, in which the poetic mode is exchanged for an expository tone. These sequences show the Butantam Institute, where snake and spider antitoxins are developed, and a rehabilitation program in the state prison. The third insert diverging from the main film, finally, is the reenactment of the Proclamation of the Independence of Brazil, an event that occurred on 7 September 1822 on the banks of the Ipiranga river by the Prince Regent, D. Pedro Alcântara e Bragança, who eventually became Emperor Pedro I. The filmmakers recreate the past in period costume, narrating this founding event of São Paulo’s pride, which should be related to the date the film was released, exactly one day before the celebrations of Independence Day in 1929.

After this staged leap into history, the film returns to contemporary life, showing us the “sweaty Cyclops building the city” (the construction workers), lotteries and gambling, charity through the giving of alms (a special effect shows a giant hand wandering through the city and distributing coins), and individual and collective sports, such as horse racing and fun in the swimming pools. Although a silent film, there is a part entirely dedicated to noise, to the urban sounds that mark the “vertiginous” growth of the metropolis. Lunch time is described as a musical syncope, as a moment of rest for the nerves and brains. The symphony does not turn into silence, but is marked by a slower rhythm before becoming erratic again with footage of printing presses, schools, and illustrious persons visiting the city. The outcome is as expected: night falls over the city. It gets dark in a tumultuous brawl, evoked by its shadows stretching out over the pavement. The city, however, does not go to sleep. By means of a scale model and an assembly of the most unlikely pictures, the final scene shows “São Paulo, formidable and Cyclopic metropolis” topped by aircrafts and zeppelins across the nocturnal sky. Kemeny and Lustig, clearly, did not hesitate to use devices ignored by most other films in this period such as travellings, lateral framing, diagonals and daring montages.15

In general, São Paulo: Sinfonia da Metrópole is a flow of images. Its dramatic effects are determined by the rhythmic curve provided by the orchestrated movements of dawn, of men in the streets, factories, and urban activities.16 The film frees itself from any commitment to theatrical representation whereas the very gestures of everyday life become the essence of this urban drama. In addition, the city is defined by continuous flows that indicate the proliferation of means of transport (people walking everywhere, horse and carriages, cars, trams, et cetera) while the urban scenery itself is often arranged in the straight lines of skyscrapers, architecture, streets, and tram tracks. Crowds and factories glorify the industry and the machine whereas the workers appear as the gears of the new metropolis in its unstoppable growth. The metropolis is also presented as a verbiage: the city appears as literate, and texts are not only present in the intertitles but are also physically present in urban space by means of newspapers, street signs, advertisements, and propaganda.17

Strikingly, São Paulo: Sinfonia da Metrópole avoids any representation of the rusty outskirts of the city—and when it moves to the city’s surroundings, it is only to show elegant suburbs. In addition, the film refuses to represent nature, which appears only in its domesticated form, like in the pleasant gardens where a romantic couple takes a stroll. São Paulo: Sinfonia da Metrópole presents the metropolis first and foremost as a site of accelerated growth, movements of people in the streets, facilities for sports, means of transport, and urban trade. In so doing, Kemeny and Lustig focus on phenomena as acceleration, fragmentation, intensity, which the medium of cinema was able to capture. This image of São Paulo as a bustling metropolis was also cherished by poet Blaise Cendrars, when he stayed there in 1926. “Here, no tradition, no prejudice ancient nor modern,” Cendrars wrote. “The only thing that counts is that furious appetite, this absolute confidence, and audacious optimism.”18 Furthermore, many of these topics materialized in cinematic narratives of São Paulo from the 1930s onwards, when the notion of a city that never stops, changing and rejuvenating forever, settled in the imagination of the inhabitants of São Paulo. When anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss lived in Brazil (between 1935 and 1939), he confirmed that São Paulo was a city of rapid cycles, perpetually young and therefore never completely sane. It was then that he called it “a wild city, as are all American cities.”19 Kemeny and Lustig represent this São Paulo, voraciously aspiring to become modern, powerful and cyclopean.