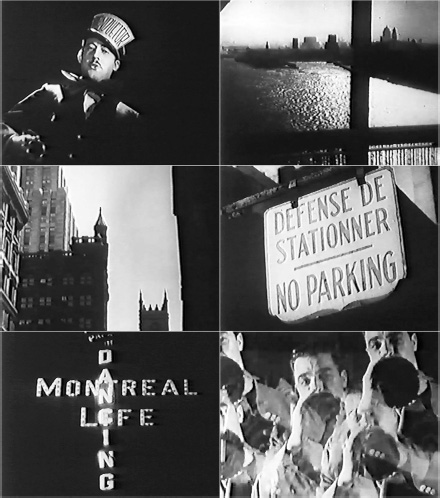

Figure 15.1 Rhapsody in Two Languages (Gordon Sparling, 1934)

Virtually unknown outside of Canada, and little-known within, Gordon Sparling’s Rhapsody in Two Languages (1934) nevertheless occupies a very unique position in the history of Canadian cinema, as does its creator. Sparling was active in filmmaking from the 1920s until the 1960s, but he is best known for his contributions to Canadian cinema in the 1930s. At a time when Canadian cinema was largely stagnant, its screens and production facilities colonized by outside interests, Sparling founded a series of short films that was dedicated to getting Canadian content produced by Canadian talent projected on Canadian screens.1 The series was called Canadian Cameos and Sparling made its support conditional to his joining the production team at Associated Screen News (ASN) in 1931.2 This Montreal-based film studio had been founded in 1920, but Sparling’s intervention greatly raised its profile, and ASN remained his home for the better part of the next 20 years, until 1954.3

Sparling was a pioneer, a filmmaker who recognized that Canadian feature filmmaking was a risky proposition and that short films provided a safer way of establishing “a foot in the door of theatrical production for Canada.”4 He was also a nationalist who had pressed the management at ASN to expand into the production of theatrical shorts in response to Fox Movietone’s expansion into Canada.5 ASN’s series of “featurettes” proved to be a huge success: Sparling eventually produced over 80 Canadian Cameos and they were screened widely in commercial theaters across Canada and beyond. As such, this series was of crucial importance to Canadian cinema. Film historian Peter Morris would later note that the Canadian Cameos series represented “Canada’s only continuing creative film effort in the Thirties, and, through international theatrical release, almost the full measure of Canada’s image on its own and the world’s screens.”6 Sparling’s commitment to theatrical shorts was not only pragmatic, however, it was also aesthetic. He was convinced that short films offered a unique opportunity “for experimentation in technique [and] ingenuity in presentation.”7 Without question, the film that did the most to fully realize this vision was Rhapsody in Two Languages.

In April 1934 ASN unveiled the latest release in its ground-breaking Canadian Cameos series, and the film that would establish Sparling’s reputation: Rhapsody in Two Languages, an ode to Montreal and modernity. The timing was appropriate, for Montreal had grown dramatically over the last 50 years: Its population alone had increased more than fivefold between 1881–1931, reaching nearly one million inhabitants, and the city had consolidated its power as Canada’s leading shipping, transportation, and financial hub.8 Depicting one hectic and animated day in the life of Montreal, Rhapsody was an 11-minute “talking picture” featuring an original score that presented the city as a bustling metropolis defined by its sharp contrasts. The “city of contrasts” trope had been a defining aspect of the city symphonies films right from the start, and it was crucial to many of the most famous of these films (e.g., Berlin, Symphony of a City, Man with a Movie Camera, and À propos de Nice), but it also figured prominently in two New York films that were released in 1931, right around the time that Sparling was leaving New York and relocating to Montreal. One was photographer Irving Browning’s City of Contrasts, an independently produced film that emerged from New York’s Film and Photo League set; but the other was a film that had been produced by Fox Movietone, ASN’s competitor. In its opening moments, Bonney Powell’s Manhattan Medley bills itself as “a camera conception of the city of inconceivable contrasts—a symphony of paradox,” and, sure enough, the images that follow play up New York’s stark contrasts: new vs. old, day vs. night, rich vs. poor, white vs. black, Occident vs. Orient, and so on. It’s a film that features many of the hallmarks of the city symphony—in terms of structure, content, and technique—but the film is unusual in that it features much more of a tourist’s vision of the city than one typically finds in these films.

Despite Sparling’s commitment to documentary representation, Rhapsody opens with an odd bit of fabulation, an arrival into the city by way of a fictitious train along an imaginary railway line on the recently opened Harbour Bridge. The audience is greeted by an actor (Corey Thomson, who doubles as the film’s narrator) playing an unconvincing, if enthusiastic conductor who sets the scene for the vision of Montreal to come:

Step right this way, ladies and gentlemen! Step aboard for a day in Montreal. Montreal, the metropolis of Canada, the city of contrasts. It’s modern! It’s old! It’s gay! It’s pensive! Feel the pulse of its million people! It’s French! It’s English! It’s Montreal!

This conceit might be perplexing, but the important thing, perhaps, is that Sparling’s film has set up a tourist’s arrival into the city, not the commuter’s arrival or the traveler’s arrival that we find in so many other city symphonies. What follows this prelude is a lively treatment of this city of contrasts from dawn to dawn, one that pays special attention to old vs. new, traditional vs. modern, young vs. old, religious vs. secular, and French vs. English, and that builds to a rhythmic and aesthetic crescendo during its lively nightclub sequences, which feature a flurry of optical effects, including multiple exposures and negative imagery.

Rhapsody can be broken down into five acts or movements, plus a prelude (the one just described), and a conclusion:

Prelude: opening credits + an arrival by train into Montreal.

Conclusion: “And it’s another day!”—it’s dawn again and the daily routine begins to repeat itself + end credits.

We can get a sense of what aspects of Montreal’s city life the film places its emphasis on by analyzing the shot composition and duration of each portion of the film. By far and away its most elaborate section, and the one that involves the greatest number of shots, the briskest editing, and the most extensive use of optical effects, is its nightlife segment. This distinguishes Rhapsody from other city symphonies that share an interest in the nocturnal city, such as Ruttmann’s Berlin and Manhattan Medley, but it also speaks to the identity Montreal had developed during the years of Prohibition in the United States as the “Paris of the North,” as well as a “wide-open” town and notorious “sin city.”9 The United States had repealed the 18th Amendment by the time Rhapsody was released in 1934, but it had still been very much in effect at the time that the film was conceived and principal shooting commenced, so although Montreal’s wild nightlife was no longer the draw for American tourists that it had been, Sparling evidently felt it was still vital to its identity.

Some film scholars would later claim that Sparling had created Rhapsody completely unaware of the city symphonies created by his European counterparts, but comparing the film with Ruttmann’s Berlin alone would suggest otherwise.10 Both films share the following sequences: an arrival by train into the city at dawn; streetcars and commuters; clocks announcing the time of day at key moments; cats, milkmen, and milk deliveries; tipsy revelers in formal wear; workers climbing steps; office workers furiously doing their work; factory scenes; tracking shots through nighttime streets; jazz bands; cocktail shakers; chorus lines; ballroom dancers; and exotic dancers. They also share a few more unusual sequences: multiple exposure sequences of city traffic, typists typing, and electrical advertisements. Some sequences in Rhapsody also bear a striking resemblance to ones found in Manhattan Medley, including a few that Berlin, Rhapsody, and Manhattan Medley all share in common (like the sequences involving stray cats, milkmen, and milk deliveries), while others are highly reminiscent of Man With a Movie Camera (especially the woman putting on her stockings in the morning routine section). One of the most telling aspects of the Rhapsody project, however, may be the promotional poster that Sparling himself created for the film. This poster was a photomontage composition that consisted mostly of images taken directly from his film,11 including an electrical sign reading “MONTREAL LIFE” that helped to tie the disparate images the modern city together, but that arranged them using the bold diagonals typical of modernist photomontages of the 1920s and 1930s. In this regard, as well, we see a powerful connection between Rhapsody and Berlin, for Ruttmann’s film had also been publicized with modernist photomontages—compositions that Ruttmann had assembled himself. One should not be too surprised by these resonances—Sparling had long been a dedicated cinephile, one who had regularly take trips to New York to binge on films in the 1920s. Even more significantly, Sparling’s formation as a filmmaker occurred when he apprenticed at Paramount’s Astoria Studios from 1929 to 1931.12 This facility was known for its European sophistication at the time, and it was the very same milieu out of which Robert Florey produced his Skyscraper Symphony (1929).13 In other words, there’s no reason to assume that Sparling was an innocent when it came to film art.

Sparling did not have the background in abstract painting and experimental cinema that Ruttmann had, but he did have a past as an amateur photographer, and aspects of Rhapsody—most notably its harbor sequences—not only call to mind similar scenes in Manhatta and Twenty- Four Dollar Island (as well as a brief sequence in Manhattan Medley), they were consistent with a line of modernist art practice in Montreal that began with the Machine Age Americanism of the short-lived art journal Le Nigog (1918–19) and extended through the paintings of its alumnus Adrien Hébert, who became known as the “poet” of the port of Montreal.14 This aesthetic was certainly not the most audacious example of modernism, but it remained a highly controversial one in Montreal in the 1930s as Quebec’s politics took a sharp turn to the right. That city symphonies such as Ruttmann’s Berlin got caught up in the culture wars of the Weimar period is well-known. But a film like Rhapsody was released into a similar cultural climate. We wouldn’t want to push this comparison too far, but both films were produced in places where debates over modernism vs. regionalism, city vs. country, and decadence vs. purity raged, places where a sharp conservative turn was associated with nationalism, corporatism, anti-communism, anti-Semitism, and a cult of the land.15 In fact, Rhapsody was released just one year after Maurice Duplessis became leader of Quebec’s newly revived Conservative Party, the beginning of a dramatic rise to power that would culminate in his becoming Premier of Quebec in 1936, and would lead to 20 years of deeply reactionary politics in Quebec, a period that came to be known as The Great Darkness.16 Montreal was already notorious for its “Regulations Governing Theaters, Play-houses, and Other Places of Amusement” ordinance of 1932, which prohibited double meanings, “bare-legged females,” profanity, and “bolshevist” and “communistic” material, but now the entire province was under the sway of a crackdown on metropolitanism.17 Given this climate, it is perhaps no wonder that ASN had greater difficulties getting Rhapsody screened in Montreal than it did in other parts of Canada, even though its “bare-legged females” were performing on stage just down the street, as Sparling liked to point out.

In any case, Rhapsody was an ambitious and sensational Canadian film that was reviewed rather extensively for a theatrical short, and that received considerable praise for its artfulness. The film also received enthusiastic testimonials from all across Canada and from as far afield as London, England. Quite single-handedly, Rhapsody was credited with having boosted the profile of the fledgling Canadian Cameos series, as well as ASN in general. And Rhapsody remained one of the highlights of ASN’s catalogue for the next twenty years. As late as 1953, Rhapsody was still getting star billing in ASN’s promotional materials, but by then the writing was on the wall for this pioneering studio. Within a few years ASN had folded—the victim of the advent of television and of a New Order in entertainment, according to Sparling—and the veteran filmmaker moved on to the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), where he finished his career.18

Strangely, at around the same time that Sparling’s career was ending, Rhapsody began to experience an unexpected afterlife. Instead of fading into obscurity, Sparling’s film was rediscovered and shown at a National Film Society of Canada screening in Ottawa in 1964 and a Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society screening in New York in 1965, and on both occasions it was compared to the work of Ruttmann and other modernist filmmakers and favorably received. This led to Rhapsody’s inclusion as part of a influential retrospective of Canadian cinema on the occasion of the nation’s centennial in 1967, one which established Sparling as a crucial link to the early history of Canadian cinema in the years to follow, and Rhapsody as an integral part of the emerging canon of Canadian cinema.19

While this attention brought Sparling and Rhapsody much-deserved acclaim, the spotlight on this particular film cast long shadows over many other key aspects of Sparling’s work, including the fact that Rhapsody was actually just one part of a series of four city symphonies that Sparling directed for ASN in the years 1934–6, and that these films form a subset of a larger group of films that he produced between 1931 and 1943, all of which shared an interest in modernization and industrialization, as well as in modernist cinematic techniques.20 The success of Rhapsody allowed Sparling to complete a series of city films, each of which took him and his crew further west: The Westminster of the West (1934) was a portrait of Ottawa that focused almost exclusively on the architecture and activities of Parliament Hill; City of Towers (1935) depicted Toronto as a city defined by its tallest structures; and Vancouver Vignette (1936) was an ode to the rapid growth of city it called a “modern, sophisticated metropolis.”21

Of these, the most interesting of the extant films22 is City of Towers. Here, Sparling borrows the same “city of contrasts” form he had used in Rhapsody in Two Languages, but maps out Toronto’s contrasts geographically instead of putting the emphasis on diurnal rhythms, so that some districts are presented to the viewer as sedate and thoughtful, while others are presented as being business-oriented and highly kinetic. The one thing that unites the city, the audience is told, are its many towers—thus, the film is broken down into six sections with self-explanatory titles like Towers of State, Towers of Learning, and Towers of Worship. Most of these sections are fairly conventionally touristic, with only the occasional sharp-angled or abstractly patterned shot thrown in to indicate a modernist sensibility. The major exception to this, however, is the film’s Towers of Commerce section, which focuses on the city’s bustling central business district, and whose narration becomes positively rhapsodic as the streets begin to throb with activity:

columns of stone, columns of steel, columns of brick, columns of hard, impersonal matter assuming a personality … imposing that personality upon 800,000 human beings … absorbing the heartbeats, the heartaches, the joys, and the sorrows … proclaiming the glory, shouting the ecstasy, bearing the grief, forming the backbone … thwarting nature’s terrors, bespeaking nature’s grandeur… . Truly, the City of Towers!

As the narration reaches a climax, so, too, does the film’s montage—a sequence that began with impressive extreme low- and high-angle shots, and panoramic views from atop some of Toronto’s tallest buildings, reaches a frenzy as we’re presented with street-level views of the busiest intersections in the entire Dominion. The editing here might not display the sophistication of the third act of Ruttmann’s Berlin, but it does share its fascination with crowds, traffic, and congestion, as well as its belief that cinema is the ideal medium for capturing this energy. Strikingly, the impression that City of Towers leaves its audience with is less of “Toronto the Good” than of “Toronto the Economic Juggernaut”—a vision that would prove prescient, as Toronto was already well on its way to displacing Montreal as “Canada’s Metropolis.”

Gordon Sparling stands as a pioneer of Canadian cinema in the years before the founding of the NFB and the impact of John Grierson, and Rhapsody, his modernist ode to 1930s Montreal stands as his most famous film. When we move beyond Rhapsody and take into account a somewhat larger survey of Sparling’s 1930s work for ASN, we get a better sense of his sensibility and the patterning that defined his work, but there’s more at stake here than just producing a more fully rounded account of a single significant, but now obscure filmmaker. For one thing, Sparling’s four city symphonies rank him as one of the most prolific filmmakers to have contributed to this phenomenon, and this output alone means that Canada’s cities are surprisingly well represented within this body of work. For another, we get a better sense of the times and of the culture Sparling was a part of, as well as a larger transformation that was occurring in the realms of visual arts and design. The life cycle of the classical city symphonies is very much a story of how avant-garde and modernist aesthetics were developed, disseminated, assimilated, adapted, and manipulated in the period between the wars. Through this process an aesthetic became a widely recognized style, so that compositions and techniques that had been at the very vanguard of film art just a few years earlier were now the stuff of commercial theatrical shorts like Powell’s Manhattan Medley or Sparling’s Canadian Cameos. They may have only been a series of urban “featurettes,” but these films provide us with a glimpse of how Canadian cities were positioning themselves as the Great Depression wore on, how social, economic, and cultural currents coursed through these films, and how a young, ambitious filmmaker seized upon this material in order to launch his career and kick-start a struggling film industry.