3 The Growth of the Popular Press

The development of the press in England, in particular the growth of the popular press, is of major importance in any account of our general cultural expansion. The vital period of development is significant in itself, from the establishment of a middle-class reading public in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, through the widening of this public to the virtually universal readership of our own time. And the newspaper, as a continuing element in this period of growth, is an obviously significant element for analysis, both because of this continuity, and because of its status as the most widely distributed printed product.

Some of the facts of the development are very difficult to establish – a few indeed are impossible, due to records lost or not kept. But there are quite enough facts to establish a general pattern, and the histories of newspapers reproduce these faithfully enough. When it comes to analysis, however, there are two general defects. There is still a quite widespread failure to coordinate the history of the press with the economic and social history within which it must necessarily be interpreted. Even more, there is a surprising tendency to accept certain formulas about the development, which seem less to arise from the facts of press development than to be brought to them. The general cultural expansion has been interpreted in a particular way, and the history of the press has been fitted, often against the facts, to this general interpretation.

The most common of these formulas is that before the coming of Tit-Bits and Answers in the 1880s, and of Northcliffe’s halfpenny Daily Mail in 1896, there was no cheap popular press in England. The basis of the new press, it is said, was the Education Act of 1870, by means of which the ordinary people of England learned to read. At this point, the formula has alternative endings. Either, as a result of this process, a popular press, the keystone of a lively democracy, could be established. Or, with the entry of the masses on to the cultural scene, the press became, in large part, trivial and degraded, where before, serving an educated minority, it had been responsible and serious.

Now these alternative endings hardly matter, and the debate between them is really irrelevant, for the fact is that to anyone who knows the history of the press, or the history of education, such an account is nonsense. It can be traced, interestingly enough, to Northcliffe, who said to Max Pemberton in 1883:

The Board Schools are turning out hundreds of thousands of boys and girls annually who are anxious to read. They do not care for the ordinary newspaper. They have no interest in society, but they will read anything which is simple and is sufficiently interesting. The man who has produced this Tit-Bits has got hold of a bigger thing than he imagines. He is only at the beginning of a development which is going to change the whole face of journalism. I shall try to get in with him.

This is the frank thinking of a speculator (and was noted as such by Gissing in New Grub Street). As an indication of attitude it is important. But it became something more. R.C.K. Ensor, in the Oxford History England 1870–1914, referred to 1870 as a watershed, and spoke of a ‘dignified phase of English journalism’, which

reigned unchallenged till 1886 and indeed beyond. Yet the seed of its destruction was already germinating. In 1880, ten years after Forster’s Education Act… Newnes became aware that the new schooling was creating a new class of potential readers – people who had been taught to decipher print without learning much else. He started Tit-Bits.

After this, the formula was firm in most educated minds, and has found its casual way into print an uncountable number of times. We find even the 1947 Royal Commission on the press saying:

The 1890s saw the introduction of newspapers sold at a halfpenny and addressed, not to the highly-educated and politically-minded minority, but to the millions whom the Education Act of 1870 had equipped with the ability to read.

But if, as commonly, we start an inquiry with an assumption like this, offered as fact when it is not fact, it is unlikely that we shall go on to ask the really relevant contemporary questions, or reach the point at which our present urgencies can be illuminated by the actual lessons of history.

The facts, it is hoped, will become clear in the account that follows. But it seems worth setting down first, in summary, the cardinal points of the history, and the questions they indicate. The newspaper was the creation of the commercial middle class, mainly in the eighteenth century. It served this class with news relevant to the conduct of business, and as such established itself as a financially independent institution. At the same time, in periodicals and magazines, the wider interests of the middle class as a whole were being served: the formation of opinion, the training of manners, the dissemination of ideas. From the middle of the eighteenth century, these functions, in part, were additionally taken up by the newspapers. In relation to the formation of opinion, successive governments tried to control and bribe the newspapers, but eventually failed because of their essentially sound commercial basis. When one of these newspapers, The Times in the early nineteenth century, claimed its full independence, it found that it was there for the taking, and with the new mechanical (steam) press as its agent, a powerful position and wide middle-class distribution, could be achieved. The daily press, led by The Times, became a political estate, on this solid middle-class basis.

Before this had been achieved, however, other points of growth were evident. Between the 1770s and the 1830s, but particularly in the last twenty years of this period, repeated attempts were made, against severe government repression, to establish a press with a different social basis, among the newly organising working class. These attempts, in their direct form, were beaten down, but a press with a popular public was in fact established, in another way. This was through the institution of the Sunday paper, which, particularly from the 1820s, took on a wholly different character and function from the daily press. Politically, these papers were radical, but their main emphasis was not political, but a miscellany of material basically similar in type to the older forms of popular literature: ballads, chapbooks, almanacs, stories of murders and executions. From 1840 on, the most widely selling English newspaper was not The Times, but one or other of these cheap (penny) Sunday papers.

In 1855, with the removal of the last of the taxes on newspapers, the daily press was transformed. A cheap (penny) metropolitan daily press, led by the Telegraph, quickly took over leadership from papers of the older type, led by The Times, and gained rapidly in an expanding lower-middle class. At the same time, a provincial daily press was firmly established. With improvements in printing, with falling prices for newsprint and with railway distribution, circulations grew rapidly, and were around 700,000 in 1880. Still, however, the Sunday press was in the lead, and by 1890 had reached 1,725,000, with a leading paper selling nearly a million. In the 1870s and 1880s, meanwhile, a new kind of evening paper, taking much of its journalistic method from the Sunday press, was successfully launched.

In the 1890s, after a period of renewed expansion in popular periodicals, the spread of the daily paper through the rapidly growing lower-middle class, especially in the large towns, was notably forwarded by a cheaper daily paper, the halfpenny Daily Mail – a conscious imitation of The Times for a different public. The basis of the change was economic, in the substitution, for the old kind of commercial class support, of a new revenue, based on the new ‘mass’ advertising. By 1900, the daily public had climbed (in a still quite gradual curve) to 1,500,000, and by 1910 to 2,000,000. The Sunday press was still well in the lead, with its older and somewhat different public.

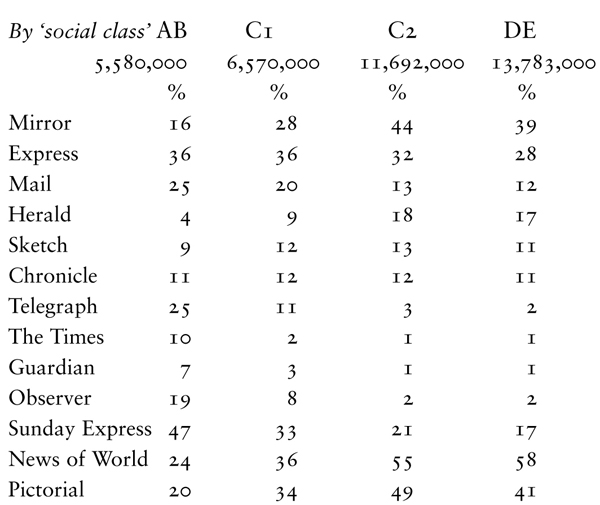

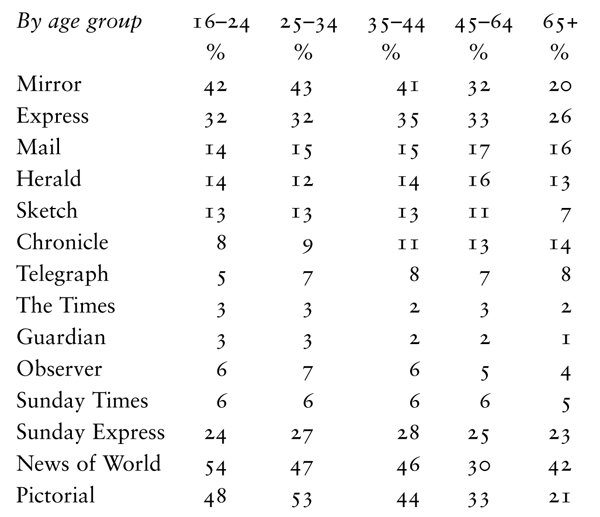

In 1920, after the demand for news in the war, the daily public was above 5,000,000, and the Sunday public above 13,000,000. It was now, in the period between the wars, that expansion of the daily press to the working class really began, although by 1937 the daily public was still smaller than the Sunday public had been in 1920. It was now, also, that the transformation of content of the daily papers radically occurred, in the course of a race for circulation and thus for the ‘mass’-advertising revenue without which the papers would be running at a great loss. The Mail was overtaken by a new type of paper, the Express, which carried the mixture of political paper and magazine miscellany much further than hitherto – a mixture clearly visible in changing appearance. The full expansion, to something like the full reading public, took place in the daily press during the Second War, reaching over 15,000,000 in 1947. The Sunday press, meanwhile, had increased to over 29,000,000. The really steep curves, and the real establishment of a popular press, occur in the Sunday press between 1910 and 1947, in the daily press between 1920 and 1947. It was an establishment, moreover, first on the lines, for the press as a whole, of the traditional content and methods of the Sunday papers since the 1820s, and, second, in terms of the new economic basis of newspapers – running at a loss and making up with the revenue from ‘mass’ advertising. In this same period, however, a new type of Sunday paper (Observer, Sunday Times), consciously imitating the methods of the older daily press, won a growing public, while the surviving older-style papers also markedly gained.

During the last decade of the major expansion, a new type of paper, the Daily Mirror, took over leadership from the Express, and is now clearly ahead. This is an even further application of the technique of combining a news sheet with a miscellany, and involved a further change of appearance. In method and content, the Mirror draws partly on the traditional Sunday newspaper, partly on the techniques of the new advertising which was now the daily paper’s commercial basis. In the 1950s, the general expansion was slowed, with the whole reading public effectively covered, and what then happened (and is still, in the 1960s, continuing to happen) was a kind of polarisation, with success going, on the one hand to the most extreme form of paper-miscellany, on the other hand to the most clearly surviving newspapers of the older style. Papers representing earlier stages of the mixture between newspaper and miscellany are losing readers.8

Now the questions one asks from these cardinal points (which need to be amplified from the fuller account that follows) are these. First, what is the real social basis of the popular press as now established? It grew, in content and style, from an old popular literature, with three vital transforming factors: first, the vast improvement in productive and distributive methods caused by industrialisation; second, the social chaos and the widening franchise, again caused by industrialisation and the struggle for democracy; third, the institution, as a basis for financing newspapers, of a kind of advertising made necessary by a new kind of economic organisation, and a differently organised public. Literacy was not a transforming factor, in itself, even supposing that the 1870 Act was the basis of popular literacy, which it was not. There were enough literate adults in Britain in 1850 to buy more than the total copies of the Daily Mirror now sold each day. Literacy was only a factor in terms of the other changes. In seeking improvement in the popular press, therefore, while it is wise to work for a higher literacy, we shall only arrive at the centre of the matter by asking questions about the social organisation of an industrial society, about its economic organisation, and about the ways in which its services, such as newspapers, are paid for.

Second, what is the communication-basis of the popular press? The eighteenth-century Advertiser, and the nineteenth-century Times, had, as their basis, the image of a particular kind of reader, in an identifiable class to which the owners and journalists themselves belonged. The twentieth-century popular press has, as its image, a particular formula, which, beginning perhaps in the 1840s, has been rapidly developed since the institution of the new advertising in the 1890s. This formula is that of the ‘mass’, or ‘masses’, a particular kind of impersonal grouping, corresponding to aspects of the social and industrial organisation of our kind of capitalist and industrialised society. The essential novelty of the twentieth-century popular press is its discovery and successful exploitation of this formula, and the important question to ask about it, while it is wise to attend to the detailed devices of the formula, is a question about the relation of the ‘masses’ formula to the actual nature of our society, to the expansion of our culture and to the struggle for social democracy.

These questions are at once the means of understanding our press in some depth, and the means of understanding the nature and conditions of our expanding culture, to which it is so important an index. To ask them, and to look for answers in the field which they open, is the real consequence of our actual press history. While we hold to existing formulas we shall ask wrong questions, or be left to the sterile debate between those who say that at any rate the press is free and those who say that at any price it is trivial and degraded. We need, to get beyond this deadlock, and the history of the press is the means.

I turn now to the actual history, in seven periods: 1665–1760, the early middle-class press; 1760–1836, the struggle for press freedom, and the new popular press; 1836–55, the popular press expanding; 1855–96, the second phase of expansion; 1896–1920, the third phase; 1920–47, the expansion completed; the 1950s, and the new tendencies within an achieved expansion.

(i) 1665–1760

The story of the foundation of the English press is, in its first stages, the story of the growth of a middle-class reading public. The first half of the eighteenth century is a critical period in the expansion of English culture, and the newspaper and periodical are among its most important products, together with the popular novel and the domestic drama. The expansion is significant, in that it took place over a wide range and at many different levels. The development of the press fully reflects the range and the levels, and sets a pattern in this kind of expansion which is vitally important in all its subsequent history.

The cultural needs of a new and powerful class can never merely be set aside, but the ways in which they are met may be determined by various legal, technical and political factors. The factors which most clearly affected the press, in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, were, first, the state of communications, in particular the postal services, and, second, the passage from State-licensed printing to conditions of commercial printing for the market. State control over printing was, in its turn, an obvious political control over the powerful new means of disseminating news and opinions.

There had been many efforts, in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, to use printing for this obvious social purpose, but all had been hampered by direct political censorship. In one form or another, the Corantos, Diurnalls, Passages and Intelligencers did their best to break through, yet all these were still, essentially, books or pamphlets. The establishment of the weekly public post in 1637 made possible a new technique, that of the news-letter, which was circulated by subscription to booksellers, and which, being handwritten by scriveners in the booksellers’ employ, escaped the restrictions on printing. This advance in freedom was, however, obviously technically regressive, and when the same freedom found a progressive technique the news-letters were left far behind. This was not to happen, however, until nearly the end of the century.9

The important technical advance, the development of a news paper instead of a book or pamphlet, in fact took place under official direction. This was in 1665, when an official Oxford Gazette was ‘published by Authority’, in the new single-sheet form. This later became the London Gazette, now only an official publication, but then a true newspaper. In the same period, however, State control of printing was being put on a new basis. The Licensing Act of 1662, to prevent ‘abuses in printing, seditious, treasonable and unlicensed books and pamphlets’, limited the number of master printers to twenty; and in 1663 a Surveyor of the Press (L’Estrange) was appointed, with a virtual monopoly in printed news. Thus, while the right technical form was being found, the conditions for its exploitation were firmly refused.

Yet the balance of political power was now evidently changing, and as 1688 is a significant political date, so 1695 is significant in the history of the press. For in that year Parliament declined to renew the 1662 Licensing Act, and the stage for expansion was now fully set. In addition to the new freedom, there was also an improved postal service, with country mails on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, and a daily post to Kent. The expansion was not slow in coming, for in the years between 1695 and 1730 a public press of three kinds became firmly established: daily newspapers, provincial weekly newspapers, and periodicals. Between them, these new organs covered the whole range of the cultural expansion.

The first daily newspaper, the Courant, appeared in 1702, and was followed by the Post (1719), the Journal (1720) and the Advertiser (1730). Many thrice-weekly morning and evening papers began publication in the same period, on the days of the country mails. At the same time, provincial weekly papers were being established: two in 1695–1700; eight in 1701–10; nine in 1711–20; five in 1721–30. In periodicals, Defoe’s Weekly Review began in 1704, and Steele’s Tatler in 1709. Almost immediately, however, a new form of State control was attempted, with the imposition of a Stamp Duty (½d. or 1d. according to size) and an Advertisement Tax (1s. on each insertion), not to raise revenue, but as the most ‘effectual way of suppressing libels’. The new form of control is characteristic of the new conditions: the replacement of State licensing by a market tax.

The pressures of the expansion in fact fairly easily absorbed these impositions. The daily press, in particular, was serving so obvious a need of the new class that hardly anything could have stopped it. A glance at its contents makes this clear, for the commercial interest could hardly have been better served. The news at first is mainly foreign, including news of markets and shipping. Of home news, a principal item is ‘the Prices of Stocks, Course of Exchange, and Names and Descriptions of Persons becoming Bankrupt’. Lists of exports and imports are given, and after these come a few miscellaneous items of such other news as marriages, deaths and inquests. Finally comes the material which was in fact to sustain the eighteenth-century newspaper: the body of small commercial advertisements. With the growth of trade, this last item became for a time the principal feature, and the Advertiser, 1730, conveniently marks this emphasis. It began as a strictly commercial sheet, and then broadened itself, when advertisements were short, to include ‘the best and freshest accounts of all Occurrences Foreign and Domestick’. It became the leading mid-eighteenth-century newspaper, and the priority it gave to advertisements, in putting them rather than news on its front page, initiated a format of obvious subsequent importance.

At the same time, however, the broader interests of the rising class were being served, at many levels, by the periodical press. The daily newspapers ordinarily abstained from political comment, not because comment was thought unnecessary but because this could obviously be more conveniently done in periodical publications. Defoe’s Weekly Review is the first of these political periodicals, and it had many successors and imitators. There was also, however, the need for social commentary, on manners and polite literature and the theatre. This was met by the Tatler, which again was widely imitated. After the first phase of establishment of these classes of periodical, a wide expansion took place between 1730 and 1760. The word ‘magazine’ conveniently marks the expansion, beginning with the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1730 and going on, in rising scale, to the London Magazine, the Universal Magazine, the Town and Country Magazine, the Oxford Magazine, the Magazine of Magazines and the Grand Magazine of Magazines. These publications illustrate very clearly the broadening cultural ambitions of the class of readers they served. Their contents vary in quality and intention: from original work that can properly be classed as literature, through polite journalism, to an obvious ‘digest’ function. It is what one has learned to recognise as characteristic of such a stage of expansion in a culture: a range of publications serving everyone from those who want a first-hand acquaintance with facts, literature and opinion, to those who want these in summary and convenient form as a means of rapid cultural acquisition. In the whole field it is an impressive record of work, though it must not be idealised. There is much good writing, but also much self-conscious ‘pre-digested’ instruction in taste and behaviour, and some exploitation of such accompanying interests as gossip and scandal about prominent persons. There is not only Steele’s Tatler, but Mrs de la Rivière Manley’s Female Tatler (Mrs Manley was the author of Secret Memoirs and Manners of Several Persons of Quality, of both Sexes); not only Johnson’s essays in the Universal Chronicle, but also the Grand Magazine of Magazines, or Universal Register, ‘comprising all that is curious, useful or entertaining in the magazines, reviews, chronicles… at home or abroad’. The fact is that when a culture expands it does so at all its levels of interest and seriousness, and often with some of these levels exploited rather than served.

Meanwhile, the daily newspaper was changing, alike in contents, organisation and ambition. Increasingly, features that had been left to the periodical press were being absorbed into the daily papers: comment, general news, and ‘magazine interest’ such as theatrical notices, light literature and reviews. This expansion took place on the basis of a solid and growing commercial function. Since the 1740s, advertising had grown in volume, and a successful newspaper was an increasingly profitable business enterprise. One mark of this development is the beginning of a new type of ownership. Ordinarily, the first papers had been the property of printers, who had welcomed their regular printing as a way of keeping presses fully occupied. From a sideline, papers were becoming in some instances a main activity – a development which as a whole is not complete until the early nineteenth century. In this situation, the floating of joint stock companies to run newspapers, the printers being hired agents rather than proprietors, was a natural commercial development of the times. The first such company was formed in 1748, to run the London Gazetteer, and the change was later to be of considerable importance.

Circulations continued to rise. A total annual sale of 2,250,000 in 1711 had become 7,000,000 in 1753. Readership was much larger than sales, for more papers were taken in by coffee-houses and similar institutions than by private individuals. The raising of the Stamp Duty in 1757 did no more to check the expansion than had the original imposition. The time was coming, in fact, when with increased prosperity the papers would aspire to a higher political status. Their political importance was already sufficiently recognised to make them the objects of persistent government bribery: Walpole, for example, paid out more than £50,000 to newspapers and pamphleteers in the last ten years of his administration. But the time was coming when the freedom of the press, as a political institution in its own right, would be seriously claimed. The key issue in this was the freedom to report Parliamentary proceedings, and here the periodicals had been in the van. Cave began to report Parliamentary debates in 1736, in the Gentleman’s Magazine. When in 1738 this was declared a breach of privilege, Cave continued to publish reports, as of the ‘Senate of Lilliput’, and in 1752 resumed direct reports, with only the first and last letters of speakers’ names. The battle was not yet won, but the claim had been staked. For the next three quarters of a century, the freedom and political status of the press were to be dominating issues in its development. For the newspaper had broken out into the open market, and had prospered: it now sought, with all those whose history had been similar, to take a greater share in the government of the country.

(ii) 1760–1836

The first number of Wilkes’s North Briton, in 1762, is a convenient introduction to the coming battle for independence. Wilkes wrote:

The liberty of the Press is the birthright of a Briton, and is justly esteemed the firmest bulwark of the liberties of this country.

By the end of the decade, the liberty had been taken, in the remarkable series of Letters of Junius in a daily newspaper of the old commercial kind, The Public Advertiser. Then, in 1771, at Wilkes’s instigation, several papers began printing full Parliamentary reports, and privilege, though not formally set aside, was successfully defied. This victory, however, was to some extent offset by Lord Mansfield’s judicial interpretation of the law of libel, in a case arising from a Junius letter. This had the effect of making the Crown, rather than a jury, decide whether a given publication was libellous, and there were several prosecutions and sentences on printers in these terms, until the Libel Act of 1792 restored the decision of substance to juries.

Yet while individual printers suffered, the press as a whole was buoyant in these years. Two very important newspapers, the Morning Chronicle and the Morning Post, were founded in 1769 and 1772 respectively. With these, the London daily press had reached the beginnings of its political establishment. The Times followed, in 1785. Although the Stamp Duty had been again raised, in 1776, circulation continued to grow. The 7,000,000 total annual sale of 1753 had become 12,230,000 in 1776, and by 1811 was to reach 24,422,000. In 1784 there were eight London morning papers, in 1790 fourteen. Distribution had been improved, first by the coming of the Mail Coach, in 1784, and then, in 1785, by the separation of newspaper distribution from the ordinary mails. The first regular evening paper appeared, as a result of these improvements, in 1788: the Star, which gained a circulation of 2,000. The Courier followed, in 1789, and reached a circulation of 7,000. The leading morning newspapers at this time had circulations varying between two and three thousand, and a profit could be shown on this. When the Morning Post temporarily declined, in the 1790s, circulation fell to 350 before closure was threatened. Meanwhile, in 1779, the first Sunday paper, the Sunday Monitor, had appeared, and was followed by many short-lived imitators and by others destined for success, The Observer (1791), Bell’s Weekly Messenger (1796) and The Weekly Dispatch (1801). In every direction, the press was expanding, but at just this time taxes on it were sharply increased. In 1789 Stamp Duty was raised to 2d., and the Advertisement Tax to 3s. In 1797, Stamp Duty went up to 3½d. In 1789 the practice of hiring out papers was forbidden, though not stopped. These measures produced a temporary decline in circulation, though demand continued to grow. In the excited political atmosphere following the French Revolution, the influence of the press was deeply feared by the government. The Tory Anti-Jacobin Review puts the issue, and its context, most clearly, in 1801:

We have long considered the establishment of newspapers in this country as a misfortune to be regretted; but, since their influence has become predominant by the universality of their circulation, we regard it as a calamity most deeply to be deplored.

The matter was not left at deploring alone. The subsidy system had been continued, and surviving accounts show substantial expenditure in 1782–3, 1788 and 1789–93. The latter years show nine papers in receipt of subsidies, from £600 p.a. to the Morning Herald and the World, through £300 to The Times to £100 to the Public Ledger. Production costs for the Oracle in 1794 show an annual expenditure of about £6,864, and for The Times in 1797 £8,112. Thus the subsidies quoted formed a notable but not necessarily decisive element in a paper’s finances: the subsidy would clearly be welcome, but at the same time the Oracle could make a profit given a daily circulation of 1,700, and The Times in fact did make a profit on a circulation around 2,000. These figures exclude overheads on the debit side, and advertisement revenue to credit, but clearly, taken overall, the commercial position of the successful papers allowed independence if it was desired. At the same time, there were other means of government influence. Direct payments were made to journalists, at least £1,637 in the year ending June 1793. Later, and rising to a peak in the 1820s, the government tended to confine its advertisements to amenable newspapers. When the situation is seen as a whole, it seems that while influence could obviously be bought, it was bought because of the strength and effect of the press, and that this strength and effect – small circulations being multiplied by multiple readership, and made financially possible by the advertisement revenue which had throughout been the key to development – would make possible the achievement of real independence whenever a determined bid was made. There were, however, new counter-measures to come. In 1815, Stamp Duty was raised to 4d., and the Advertisement Tax to 3s. 6d. As a direct result of these new impositions, an important new factor was introduced into press development. Cobbett, by dropping news and concentrating on opinion, sold his Political Register unstamped, and at 2d. weekly achieved the extraordinary sale of 44,000 (nearly half a million in actual readership). Wooler began his Black Dwarf in 1817, and achieved a sale of 12,000. Here, in these critical years, a popular press of a new kind was emerging, wholly independent in spirit, and reaching new classes of readers. The marked rise in the political temperature was creating a fully independent political press, and behind Cobbett and Wooler in this new spirit, if not in opinion, were the outspoken new quarterlies (The Edinburgh Review, 1802, and the rival Quarterly Review, 1809, each sold 14,000 in 1818), the Radical weeklies (News, 1805, and Examiner, 1819), and the growing independent spirit of The Times (Barnes was made editor in 1817). The spirit of independence came from all these sources, but Cobbett and Wooler were extending it to a new public. The government was not long in counter-attack: the Circular Letter of 1816, and then two of the Six Acts of 1819, were directly aimed at suppressing press opinion (‘blasphemous and seditious libels’), and the power of the new popular press was, if not crushed, at least gravely weakened. Lord Ellenborough explained the government’s attitude clearly:

It was not against the respectable Press that this Bill (Newspaper Stamp Duties Act, 1819) was directed, but against a pauper press.

Ever since this period, there has been an important factual split between the ‘pauper press’, expressing new kinds of political and social opinion, and the ‘respectable press’, advancing to financial independence and editorial independence within the terms of ‘respectable opinion’. It is easy to write the history of the press in terms of the latter alone, but the history of the independent radical press is fundamentally important. Against open repression, Cobbett, Wooler, Carlile, Hetherington and many others fought hard and well, and the Chartist press was an important temporary success. But the economic basis of such papers was and has remained profoundly difficult. As the line is followed down through Blatchford and Lansbury to the Daily Worker and Tribune of our own day, it is a story of continual financial pressure met by persistent voluntary or ill-paid effort, not only by journalists but by collectors and sellers serving a cause rather than a commercial enterprise. The resources of the ‘respectable press’, in advertising revenue and organised distribution, have hardly ever been available to this kind of paper, yet the new ventures have kept coming, in direct relation to phases of political change. Without this dissenting press, the history not only of journalism but of politics and opinion would be very different.

The fact is that the economic organisation of the press in Britain has been predominantly in terms of the commercial middle class which the newspapers first served. When papers organised in this way reached out to a wider public, they brought in the new readers on a market basis and not by means of participation or genuine community relationships. As the new public appeared, in the time of Cobbett, the beginning of this long history was evident. The community as a whole was not providing its newspapers, but having them provided for it by particular interests. The radical press diverged, on a political basis, while the ‘respectable’ press went on to commercial independence, not only from the government, but eventually from the society.

The years between 1820 and 1850, in which the independent radical press made its first sustained effort, saw The Times move to a new position. Opposing the government on Peterloo, taking the popular side in the Queen Caroline controversy, it steadily emerged as the principal organ of ‘respectable’ Reform, with a coherent and growing middle-class public. Its sales had reached 7,000 by 1820, and in the Caroline controversy rose temporarily to more than 15,000. With its more radical rivals openly suppressed, it moved ahead on the basis of its solid commercial organisation, with growing advertising support from the class which it politically represented. That The Times took the lead, rather than some other paper of the same general kind, is due to the combination of this economic basis for independence with the decisive desire for it, in the adoption of a Reform policy in the critical years between 1815 and 1832. There is another, technical, reason. From its foundation, The Times had been closely connected with improvements in printing (it was in fact founded to advertise the new ‘Logographic’ press). Now, in this decisive period, it was always technically ahead. The first steam printing machine in the world printed The Times in 1814 (after experiments since 1807). From 250 sheets, the hourly rate was raised to 1,100 and then 1,800 (900 on both sides), and further improvements, in The Times office, raised this by 1827 to 4,000 on both sides. Expansion of circulation had been limited, previously, by just this printing-rate factor. Thus, its commercial status, its policy of middle-class reform and its technical superiority gave The Times its decisive lead. The factors are interrelated, for alike in its commercial, political and technical elements, The Times was the perfect organ of the middle-class reading public which had created the newspaper press, and was now carrying it with it to a share in the government of the country.

Certain other aspects of press development in this period must be briefly noted. The most important is the growth of the Sunday papers, whose beginnings have been noted. By 1810, these had circulations well above those of the daily papers, with a leading circulation of 10,000, which was not to be reached by The Times until the 1820s. Most of the leading papers were for Reform, and had an important political influence. At the same time, however, led by the Dispatch, they were beginning to give a good deal of space to detailed accounts of murders, rapes, seductions and similar material, and also to sport (racing, wrestling and prize-fighting). From 1815 on this tendency is clearly marked, and a typical front page of the 1820s, from Bell’s Life in London, describes its contents as ‘combining, with the News of the Week, a rich Repository of Fashion, Wit and Humour, and the interesting Incidents of Real Life’, which in practice means a column of foreign news, a column report of a lively election meeting, half a column of general domestic news, an account of some ‘amusing cases’ of corpulency and a miscellany including reports of two murders, a prison-break attempt and a robbery. The style of reporting is direct, and there are only small headlines. Since the increase in Stamp Duty, all papers had used small and close print, and avoided any waste of space. All are consequently very difficult to read compared even with eighteenth-century papers. It should be noted, incidentally, that repeated attempts were made to declare Sunday newspapers illegal, but in spite of great strength of feeling in the matter, all the attempts failed. While allowing for the terms of polemic in this context, it seems probable that the Sunday papers reached poorer people than did the ‘respectable’ daily press.

The other main development in this period was in magazines. The successful quarterlies were joined by such monthlies as Blackwood’s (1817) and the London Magazine (1820), and by a new type of weekly, widely regarded as ‘scandalous’, in John Bull (1820), which quickly achieved a 10,0000 circulation. There were successful new literary weeklies, and then, in the early 1830s, the extraordinarily successful cheap magazines, Chambers’, Penny and Saturday, all founded in 1832, which achieved circulations varying between 50,000 and 200,000 – a decisive expansion into a new reading class. However, though intended for the working class, these magazines seem largely to have been bought by middle-class and lower-middle-class people, who were still starved of print. It was said in 1830 that a middle-class household with an income of £200–300 p.a. could not afford a taxed daily paper at 7d. per issue, and it was evidently to such people that the penny magazines mainly appealed. The expansion of daily newspapers into this public had to await the next important legislation affecting the press, which initiated a new period.

(iii) 1836–55

In 1836, Stamp Duty was reduced from 4d. to 1d., and in 1833 the Advertisement Tax had been reduced from 3s. 6d. to 1s. 6d. per insertion. These changes led to a considerable expansion, both in the daily press, dominated now by The Times, and, more remarkably, in the Sunday press.

Though at exceptional times in the twenties the circulation of The Times had risen to above 15,000, its average circulation in 1830 was about 10,000. This rose a little in 1831, but by 1835 was distinctly lower than it had been in 1830. The political importance of the paper was already established, but its next phase of expansion did not begin until after the 1836 reduction, and then most notably in the 1840s. From 11,000 in 1837 it climbed to 30,000 in 1847, and continued to climb until it had reached nearly 60,000 in 1855. The surprising thing, at first sight, about these figures, is that the rise in circulation was not even greater, for The Times now had no real competitor – the other dailies were all still below 10,000. The key is price, for at 4d. or 5d. a paper of one’s own was limited to a still narrow income range. The Daily News (1846) reached a circulation of 22,000 at 2½d., but was insufficiently capitalised and fell back.

Meanwhile, however, masked from normal interest by the rise of The Times, the expansion that one looks for was taking place in the Sunday press. Already by 1837 two Sunday papers, the Dispatch and Chronicle, were selling about 50,000 an issue, and in the 1840s there is a remarkable general rise, in a fiercely competitive sphere. The two typical papers are Lloyd’s Weekly (1842) and the News of the World (1843). By 1855, both had circulations in the region of 100,000. The estimated total Sunday circulation in 1850 was 275,000, as against 60,000 for total daily circulation. Here, it is clear, is the first phase of expansion of the modern commercial press.

The contents of Sunday papers in the 1820s have been noted, and the new papers of the 1840s were their true successors, alike in their predominantly Radical tone and in their selection of news. At first, however, to avoid even the 1d. stamp, Lloyd’s Weekly published no actual news, but serial stories and fictitious news, with ample illustrations. By 1843, however, it had conformed to the older style, and a distinctive ‘Sunday paper look’ had been established. A few examples can be given. From 27 February 1842, there is Bell’s Penny Dispatch, subtitled Sporting and Police Gazette, and Newspaper of Romance. The main headline is ‘Daring Conspiracy and Attempted Violation’, and this is illustrated by a large woodcut and backed by a detailed story. This was an ordinary format, though it should be noted that the first number of the News of the World gives its (unconnected) ‘Extraordinary Charge of Drugging and Violation’ a very small headline and no illustration.

The provenance of this class of journalism is in fact not far to seek. There is a long history of chapbooks and ballads carrying this kind of material, especially in relation to murders, executions and elopements. These had been exceptionally popular in the eighteenth century, and the woodcut illustration, with title headline, had been typical of their format. These continued into the nineteenth century, and the circulation of comparable fiction similarly expanded, but the time came when the newspaper, with its advertisement revenues, its political news and opinion, and its superior techniques, was clearly the most effective means of buying and selling the same material. Just as the eighteenth-century newspaper had absorbed a proportion of ‘magazine interest’, so these nineteenth-century papers absorbed the chapbook, ballad and almanac interest, and at a much cheaper price. This is the recurring tendency in the history of journalism: the absorption of material formerly communicated in widely varying ways into one cheaply produced and easily distributed general-purpose sheet. The economics of the newspaper business had, from the beginning, set this course, and it is clear how appropriate these factors of concentration and cheapness were, in a continually expanding culture. A wide range of interests was being brought into a literate form, and the pioneer of each expansion was the cheapest and most extensive print.

(iv) 1855–96

In 1855 the last penny of the Stamp Tax was removed, and in 1853 the Advertisement Tax had also finally disappeared. These changes came at a time when the press was already expanding, and also when new techniques in news collection and in distribution were beginning to be widely exploited. The combined effect of these factors was a new and remarkable phase of general expansion. Before we turn to examine this, however, we should try to make some estimate, in social terms, of how far the expansion had already gone, and of other social factors, such as literacy, which were obviously to affect it.

A distinction must be clearly drawn between the daily and the Sunday press, if we are to understand this process of expansion with any accuracy. The impression one gains, from the beginning of Sunday newspapers, is that a class different from readers of the daily press was being catered for. From the very day of their publication, they were never part of the ‘respectable press’, and, in the first decades of the nineteenth century, their readers were commonly identified as the ‘lower classes’. Yet a typical Sunday paper of the 1820s sold at 7d., on a par with the daily papers, and at this price few even among middle-class people would normally have bought them. The key here, as in the earlier history of the daily press, is buying by institutions. New coffee-houses were started, at which nearly a hundred papers and magazines were available, and a typical price for reading at one of these, through the extended hours made possible by gaslight, was 1d. Papers were also collectively bought, and even read aloud, in workshops, but the public house and the barber’s shop were, increasingly, the main reading places. In both these places, Sunday morning was the most popular time, and this undoubtedly is the explanation of the lead in expansion that was taken by the Sunday press in the first half of the nineteenth century; a lead, it should be noted, that has been maintained to our own day. Even as the price of papers came down, and more people could buy private copies, the Sunday papers retained their advantage, since they appeared on the only day on which the majority of people had any real leisure. The figures already quoted for 1850 – 275,000 total Sunday circulation, 60,000 total daily – show clearly enough the two publics, and the disparity in readership was probably even greater than this, since it seems likely that a higher proportion of Sunday papers were collectively bought and read at this time. When it is further remembered that distribution was to a large degree still concentrated in London, it would seem that by mid-century a Sunday press that can be genuinely called popular was firmly established in the capital, and that the history of the expansion as a whole must be rewritten in these terms. The daily press expanded, through the rest of the century, largely into an expanding middle class. The history of the popular press, in the nineteenth century, is the history of the expanding Sunday press, aimed at a largely different public.

Between 1816 and 1836, the period of the 4d. Stamp Tax, there was a 33% rise in newspaper sales. Between 1836 and 1856 the rise was 70%. In the quarter-century following 1856 the rise was at least 600%, and the major expansion had begun. As a direct result of the 1855 tax abolition, two new elements appeared: a cheap metropolitan daily press, and a widespread provincial daily press. While these rose and flourished, the Sunday papers and the more expensive daily papers also reached out to large new circulations.

Conditions for expansion were exceptionally favourable at this period, quite apart from the effect of the tax abolitions. There was still regular improvement in printing techniques: the hourly rate of 4,000 in 1827 had been raised to 20,000 in 1857. The price of paper was falling again: a ream which had cost 21s. in 1794 cost 55s. in 1845, but by 1855 was down to 40s. Paper duty was abolished in 1860, and there was considerable subsequent improvement in manufacturing techniques: the price of this main raw material continued to fall. General improvement in commerce led to a rising demand for advertising space, although most newspapers were slow to increase their rates and take full advantage of this. In the collection of news, the electric telegraph had been available since 1837, and had been regularly used since 1847, though its full exploitation was not to come until the 1870s. Distribution by railway was becoming widely available, and by 1871 sale-or-return distribution to railway bookstalls had become established. All these factors operated within the general mood of the whole economy, which was confident and expansive.

The repeal of the Stamp Tax became law on 20 June 1855, and on the same day the newspaper appeared which for forty years was to lead the expansion of the daily press: the Daily Telegraph. Within three months it was selling at 1d., and by 186o it had a circulation of 141,000. The Morning Star, at 1d., appeared in 1856, and the Standard reduced to 1d. in 1858. With the News and Standard as principal competitors, the Telegraph had reached nearly 200,000 in 1870, 250,000 in 1880 and 300,000 in 1890. From the 1870s, new machines were printing at 168,000 an hour.

The Daily Telegraph, which set the pace in this rise of the cheap daily press, was conceived as serving ‘an entirely new public who never saw the weeklies and monthlies’: it was ‘the paper of the man on the knifeboard of the omnibus’. In style it had certain obvious differences from the early Victorian Times, but it was not, of course, even in the daily press, the first newspaper to adopt a light style of journalism. The pioneers in this had been the Morning Post and the World, back in the 1780s, and we must remember that the Victorian Times was itself much heavier in manner than at any earlier stage in its career. Labouchère observed of the Telegraph that

when persons entirely unconnected with literature themselves are the owners of newspapers, they naturally sacrifice all decorum to the desire to make the journal a remunerative speculation.

The owners of the Telegraph were the printing family of Levy, but Labouchère’s implication that the separation of literature and journalism was new is impossible to accept. The separation between writers and journalists is clear, in spite of occasional overlaps, before the end of the eighteenth century, and printer-ownership had always been common. What is certain is that Levy had a new kind of paper in mind: ‘what we want is a human note’, he instructed new entrants to the Telegraph, and politics must not be assumed to be the sole interest of its readers. Matthew Arnold, observing the result, called it the ‘new journalism’.

In terms of contents, it is not really new. But undoubtedly, in this period, an attention to crime, sexual violence and human oddities made its way from the Sunday into these daily papers, and also into older papers like the Morning Post. As early as 1788, the Morning Post had written:

Newspapers have long enough estranged themselves in a manner totally from the elegancies of literature, and dealt only in malice, or at least in the prattle of the day. On this head, however, newspapers are not much more to blame than their patrons, the public.

The Victorian Morning Post had become respectable, but under Borthwick (1852–1908) it certainly published very full reports of crimes. The ‘new journalism’ is complex, because the expansion was producing something new: distinct levels of seriousness within the daily press. The period from 1855 is in one sense the development of a new and better journalism, with a much greater emphasis on news than in the faction-ridden first half of the century. In a period which saw the consolidation of sentiment from the middle class upwards – a unity of sentiment quite strong enough to contain constitutional party conflicts – most newspapers were able to drop their frantic pamphleteering, and to serve this public with news and a regulated diversity of opinion. On the other hand, this change in political atmosphere had to a large extent removed politics from the primary place which it had in the cheap press of the first half of the century, and allowed the new emphasis on a more general news miscellany. The Times and a few of the older papers served the established classes with a new and more objective journalism; the Telegraph and the new papers served a new lower and rising middle class, with a new journalism in which liveliness was applied, not only to politics, but to other kinds of news. The ordinary reaction of readers of The Times was the same as the later reaction to the halfpenny Daily Mail: ‘lively, but crude and vulgar’. It must again be emphasised that no lion of the new journalism would have had anything to teach eighteenth-century journalists in the matter of crudeness and vulgarity, but, given the rate of the expansion, the emphasis was now very evident. ‘Extraordinary Discovery of a Man-Woman at Birmingham’, announced the Telegraph in 1856; ‘Furious Assault on a Female’, in 1857; and so on and so on. Burnham (a descendant of the Levy family, who remained associated with the Telegraph) writes in his history of the paper:

Reviewing the files, the honest biographer cannot dispute that the Daily Telegraph thrived on crime.

Such items as a three-column description of the hanging of a woman remind us that a popular old item in cheap literature was now establishing itself in the daily press.

There is also, at this time, an evident change in the style of reporting, due to the now regular use of the telegram. The older style was, at its best, that of books; at its worst, what the language textbooks still call ‘journalese’ (which has survived longest, significantly, in local newspapers, which use telegrams so very much less). The desire for compression, to save money on the wire, led to shorter sentences and a greater emphasis of keywords. There is often a gain in simplicity and lack of padding; often a loss in the simplification of complicated issues, and in the distorting tendency of the emphatic keyword. The balance in these issues has ever since been crucial in newspaper style.

In one other way, the Daily Telegraph was a pioneer. It shared with The Times and others the organisation of public appeals, but it was a leader in organising public functions (such as bringing 30,000 children to Hyde Park for the 1887 Jubilee), and in self-advertising stunts, such as the campaign to keep the elephant Jumbo, in 1882. On the other hand it was still, typographically, conservative: that is to say, it adhered to the dense ‘daily paper’ look, which had been established in the expensive days of stamped paper and which had already been abandoned by the Sunday press. The clearer layout and rather larger headlines of the American press of the period (itself roughly comparable to the mid-twentieth-century news pages of The Times) were frequently condemned and certainly neglected. To be classed with the Sunday papers was really what the cheap daily press feared.

Meanwhile, from 1855, a flourishing daily provincial press was being established. Seventeen new papers of this kind were established in 1855 alone, and the development of news agencies increasingly freed them from dependence on the London press. The most successful reached circulations of up to 40,000. Though this is small for the period, the spread of so many of these papers represents a considerable further expansion of the newspaper public. Because of their provincial position, they escaped the competition for different levels of the public which was appearing in the London daily press. Seeking to serve all the readers in their area, they followed a general rather than any angled policy. It is no accident that several of them have developed into some of the best newspapers of our own time.

The forces making for cheap newspapers gathered strength as the press moved into the 1870s and 1880s. An unsuccessful halfpenny newspaper (the London Halfpenny Newspaper) had appeared in 1861, but there were successful halfpenny papers in the provinces from 1855. In London, the evening Echo came out at a halfpenny in 1868, and it was in evening papers, in the seventies and eighties, that this new stage of the cheap press began. With the rise of interest in sport, particularly football, the evening paper had a new function, and the new London evenings of the eighties (Evening News, 1881; Star, 1888) were eventually to found themselves on this as a main interest. The Evening News was at first unsuccessful, as a political paper financed by the Conservatives, but was made successful by Northcliffe in the nineties. By then there was a successful model, the Star, which in method is a landmark. Techniques such as the interview, the crossheading and American-style headlines had been introduced by Stead’s Pall Mall Gazette (founded 1865; edited by Stead from 1883), and these and other features of the new journalism were taken further by O’Connor’s Star. O’Connor promised:

We shall have daily but one article of any length, and it will usually be confined within half a column. The other items of the day will be dealt with in notes terse, pointed and plain-spoken. We believe that the reader of the daily journal longs for other reading than mere politics, and we shall present him with plenty of entirely impolitical literature – sometimes humorous, sometimes pathetic; anecdotal, statistical, the craze of fashions and the arts of housekeeping – now and then, a short dramatic and picturesque tale. In our reporting columns we shall do away with the hackneyed style of obsolete journalism; and the men and women that figure in the forum or the pulpit or the law court shall be presented as they are – living, breathing, in blushes or in tears – and not merely by the dead words they utter.

The description is apt, but O’Connor’s policy is a landmark, not a revolution. The tendencies that have been noted in the cheap morning papers were now being extended in the new product, the cheap evening paper. The essential novelty of the Star is that the new distribution of interest which the second half of the nineteenth century had brought about was now typographically confirmed. From now on, the new journalism began to look like what it was.

The first issue of the Star sold 142,600 copies; the Daily Telegraph was still at around 300,000. But the really big circulations were still in the Sunday press. In 1855 the total circulation of the Sunday papers had risen to about 450,000, with the leading paper at 107,000. By the end of this period, total circulation was about 1,725,000, and the leading paper, Lloyd’s Weekly News, was at 900,000 in 1890, and 1,000,000 in 1896. As previously emphasised, the growth of a large circulation press was, from the 1820s, led by the Sunday press, and the existence of circulations like these, before Northcliffe, is a radical factor in assessing the nature of the ‘Northcliffe Revolution’. The contents of these successful Sunday papers are what one would expect from their tradition. The Jack-the-Ripper murders, for example, did much to push Lloyd’s Weekly News towards the heights. Also, the Sunday papers gave the news of the whole week, and were thus welcome to a public which still, after the expansion noted, did not buy a daily paper.

(v) 1896–1920

When the expansion of the period 1855–96 is reviewed more closely, it becomes evident that the most rapid advance came in the period 1855–70, and that there was then a slowing down. Circulation of daily papers trebled between 1855 and 1860, and doubled again between 1860 and 1870. Between 1870 and 1880 the expansion is just under 30%; between 1880 and 1890 about 12%. On the other hand, the main expansion of circulation in the provincial daily press came between 1870 and 1890 and the evening press was growing markedly from 1880 on.

There are some explanatory factors within the press industry itself, in particular the growing importance of a new kind of advertising. The commercial prosperity of the old newspapers had depended on a large number of small advertisements, of the kind we now call ‘classified’. In other media, notably billposting, the style of advertising had been changing since the 1830s, but the attitude of the press remained cautious. In particular, editors were extremely resistant to any break-up in the regular column layout of their pages, and hence to any increase in display type. Advertisers tried in many ways to get round this, but with little success, and the pressure on newspapers to adapt themselves to techniques drawn from the poster (which were eventually really to change the face of journalism) began to be successful only in the 1880s. The change had come first in the illustrated magazines with a crop of purity nudes and similar figures advertising pills, soaps and the other pioneers of new advertising methods. Eventually, with Northcliffe in the lead, the newspapers dropped their column rule, and allowed large type and illustrations. It was noted in 1897 that ‘The Times itself’ was permitting

advertisements in type which three years ago would have been considered fit only for the street hoardings

while the front page of the Daily Mail already held rows of drawings, from the new department stores, of rather bashful women in combinations. Courtesy, Service and Integrity acquired the dignify of large-type abstractions.

Behind these changes were important changes in the economy. The great bulk of products of the early stages of the factory system had been sold without extensive advertising, which had grown up mainly in relation to novelties and fringe products. Such advertising as there was, of basic articles, was mainly by shopkeepers: the classified advertisements which the newspapers had always carried. In this comparatively simple phase, large-scale advertising and the brand-naming of goods were necessary only at the margin, or in genuinely new things. In the second half of the century the range widened (branding is especially notable in the new patent foods) but it was not until the 1890s that the emphasis deeply changed. The Great Depression which in general dominated the period from 1873 to the middle 1890s (though broken by occasional recoveries and local strengths) marks the turning point between two moods, two kinds of industrial organisation and two basically different approaches to distribution. After the Depression, and its big falls in prices, there was a more general and growing fear of productive capacity, a marked tendency to reorganise industrial ownership into larger units and combines, and a growing desire to organise and where possible control the market. Advertising then took on a new importance, and was applied to an increasing range of products, as part of the system of market control which, at full development, included tariffs and preference areas, cartel quotas, trade campaigns, price fixing by manufacturers and economic imperialism.10 There was a concerted expansion of export advertising, and at home the biggest advertising campaign yet seen accompanied the merger of several tobacco firms into the Imperial Tobacco Company, to resist American competition. In 1901, a ‘fabulous sum’ was offered for the entire eight pages of the Star, and when this was refused four pages were taken, to print

the most costly, colossal and convincing advertisement in an evening newspaper the wide world o’er.

The system of selling space changed, from the old eighteenth-century shops which ‘took in’ newspaper announcements, through systems of agents and brokers, to the establishment of full-scale independent advertising agencies, and, in the newspapers, full-time advertising managers who advanced very rapidly from junior to senior status. Pressure was brought on the newspapers, by advertising agents, to publish their sales figures. Northcliffe, after initial hesitations about advertising (he wanted to run Answers without it), was the first to realise its possibilities as a new basis for newspaper finance. He published his own sales figures, challenged his rivals to do the same, and in effect created the modern structure of the press as an industry and an expression of market relationships with the ‘mass reading public’.

The production costs of newspapers were in any case increasing, if a large circulation was to be won. By tying the policy of newspapers to large circulation, Northcliffe found the formula and the revenue from the new advertising situation. He was then able to make quite rapid technical advances in journalism itself. He started the halfpenny Daily Mail in 1896 with new and expensive machinery (new rotary presses had raised the hourly printing rate to 200,0000, and the Linotype typesetter, which came into use in the 1890s, had achieved a rate ten times as fast as that of a hand compositor), and also with new arrangements for rapid sale (by 1900 he had set up separate printing of the same paper in Manchester). The improvements meant a considerable cut in the price of a single copy, if a large circulation could be achieved, and the new scale of advertising revenue was a capital factor in the necessary investment. The true ‘Northcliffe Revolution’ is less an innovation in actual journalism than a radical change in the economic basis of newspapers, tied to the new kind of advertising.

Northcliffe had begun, like Pearson who was to found the Daily Express in 1900, in the periodical business. There had been two phases of growth in this field since the penny magazines of the 1830s: first, the rise of illustrated magazines, from the 1840s, reaching circulations of 200,000 and above; second, the development of consciously light weeklies, in the sixties and seventies (Vanity Fair (1868), World (1874)). In 1881, a new phase started, with Newnes’s penny Tit-Bits, and its subsequent imitators Pearson’s Weekly and Northcliffe’s Answers. Essentially these represent an emphasis of the ‘miscellany’ trend in the daily papers since 1855, and in the Sunday papers from the 1820s, but now separated altogether from news in the ordinary sense. The ‘bittiness’ of these weeklies has often been adversely noticed, and the reaction of this method on the reporting of serious news is certainly deplorable. But the right emphasis, finally, is on the similarity of their function to that of earlier periodicals, at particular stages of cultural expansion: the mid-eighteenth-century magazines, the penny magazines of the thirties. There is a marked ‘popular educator’ emphasis, particularly in Northcliffe, and the lowering in quality, despite this, is a significant symptom of general cultural history: in particular of the increased distance of their promoters from real education and literature. The existence of marked cultural ‘levels’, of real cultural class-distinctions, is much more evident in the 1880s than in either of the earlier periods. Moreover, many of the people who were serving real popular education in late Victorian England would, at an earlier stage, have been serving it through the press. Pearson, Newnes and Northcliffe were speculators, in the strict sense. The circulation of their periodicals was deliberately built up by advertising stunts: some an exploitation of the uneven development of services (such as the free insurance with readership which Newnes started, and which was to be a major selling point in the popular press until the 1930s); others in the form of gambling (sovereign treasure hunts, £1 a week for life for winning a guessing competition, and so on). At least two of the latter were soon declared illegal, but by then the trick had been done: not only in getting readers, but in getting money for further investment in this kind of press. For example, Northcliffe’s Answers sold 12,000 of its first issue, and at the end of a year sold 48,000. Then came the £1-a-week-for-life competition, later judged illegal, and with it sales climbed in the second year to 352,000. Again it is not so much the journalistic novelty, in the strict sense, that marks the advance but the appearance of a new kind of sales and advertising policy. The tenfold increase in Northcliffe’s profits enabled him to expand: first to other periodicals, Comic Cuts, Forgetmenot and Home Chat, then to buying the Evening News and finally, on the success of these new enterprises, to the Daily Mail.

In 1896 the leading daily paper, the Telegraph, was selling around 300,000 copies: after its initial rapid expansion it had reached a relatively static period. Northcliffe, with his halfpenny paper based on a different economic conception, took the expansion into its next stage. At first the Mail’s average sale was about 200,000, and in 1898 over 400,000. By 1900 it had reached 989,000, and a new period had decisively come. It must be emphasised at this point that, by comparison with the Sunday papers, the Mail was relatively traditional in method: there were advertisements on its front page, and the main news-page was similar to the new evening papers in layout, with single-column headlines, crossheads and a general lightening of the page. It looked, and was meant to look, not unlike the existing morning papers; its changes were matters of degree. Its success, and its dominance of the press in its immediate period, are remarkably similar, in analytic terms, to the rise of The Times earlier in the century. For, first, it was based on a clear conception of the economic basis of a newspaper – a large volume of advertising interacting with circulation; second, it was technically in the lead, both in production and in distribution methods; third, it pursued a popular political policy – the Imperial sentiment in the Mail corresponding to the Reform sentiment in The Times. Just as The Times reached its first peak with the Reform Bill controversy, the Mail reached its first peak with the South African War. The Times’s public had been the commercial middle class; the Mail’s, primarily, was the lower-middle class of small businessmen, clerks and artisans. The effect of the success of the Mail was to double the daily newspaper buying public in, the period 1896–1906, and then, with its competitors, to double it again by the outbreak of war in 1914. The expansion is striking, but it must be remembered that even after the further increase during the war years, which for obvious reasons brought a considerably increased demand, daily newspaper buyers were still, in 1920, only 5,430,000 as compared with over 15,000,000 in 1947. Large-scale expansion of the daily newspaper into the working-class public did not take place until the years between the wars, and the war of 1939–45. The Sunday press was considerably ahead, throughout. Indeed, in this period 1896–1920, which appears to be dominated by the rise of the Daily Mail, the biggest expansion is again in the Sunday papers. By 1920, these sold 13,000,000 – nearly two and a half times the total daily newspaper public, and a figure not to be reached by the daily press until the war years of 1939–45. The history of the popular daily, evening and weekly press is, throughout, an expansion of these types of paper into a public already served by the Sunday press. Yet in nearly all discussions of the history of the press this fact is ignored, in favour of the idea of a new public which had read nothing until the 1870 Education Act had taken effect.

The real novelty of this period, it must again be emphasised, is a change in the economics of newspaper publishing. The effect of the Daily Mail, embodying the new conception, on the existing papers, conceived in older ways, is very striking. The Times, of course, had already been outdistanced by the Telegraph, and this, in social terms, seems to record the increasing emphasis on the division of the middle class into upper and lower sections, with the Telegraph serving the numerically larger latter. From 1870 the circulation of The Times had been declining; by 1908 it was down to less than it had been in 1855, and it was bought by Northcliffe, after a struggle with Pearson. The Telegraph, itself outdistanced by the Mail, lost readers slowly – it was down to 180,000 by 1920. Of the other popular penny papers, the Standard declined heavily, and ceased publication in 1917, while the News also declined until it lowered its price to ½d. These facts are significant in showing that the Mail did not serve only a new daily public, but a substantial part of the older public.

Following Northcliffe, Pearson started a daily paper of the new type (Morning Herald, later Daily Express) in 1900. The other member of the trio of penny-weekly publishers, Newnes, had tried and failed with a penny paper, the Daily Courier, in 1896. In terms of journalistic method, the Express was more novel than the Mail: it had news on its front page from the beginning (following the fashion of the successful cheap evening papers), and was the first to introduce streamer headlines. Then Northcliffe introduced another new paper, the Daily Mirror (1903), which failed in its original design as a paper for women, but succeeded when it was reduced to a halfpenny and turned into the first picture-newspaper. From 1911 on, the Mirror had an even larger circulation than the Mail – it reached its million (the first daily paper to do so) in 1911–12.

Thus the change in the economics of newspaper publishing led to changes in methods of ownership, of far-reaching importance. Occasionally, in earlier periods, the same printer or proprietor had owned two or three small-circulation papers but the rule, throughout, had been the ownership of a single paper, by a printer, a printing family or a joint-stock company. Now, around the new kind of speculative owner, whole groups of papers and periodicals were being collected or begun. Capital was built up with a first successful enterprise in the penny-weekly field, then invested in new periodicals, which in their turn were the basis for starting new papers or acquiring old ones. Thus Answers was capitalised to start the Daily Mail and then the Daily Mail was capitalised, the first time a daily newspaper had gone to the investing public. By the end of 1908 Northcliffe had not only his group of periodicals, but the Daily Mail and Daily Mirror as new enterprises, and The Times, two Sunday papers (Observer and Dispatch) and an evening paper (News) acquired. Pearson, at the same time, had his group of periodicals, and then the Daily Express, new, and the Standard and Evening Standard (including the St James’s Gazette) acquired. Other similar organisers were waiting in the wings, and among new papers founded in this general way were the Sunday Pictorial (Rothermere, 1915), Sunday Graphic (then Illustrated Sunday Herald; Hulton, 1915 – Hulton already owned the Sporting Chronicle, Sunday Chronicle, Daily Dispatch and Daily Sketch); Sunday Express (Beaverbrook, 1918). Thus, in the general expansion, and conditioned by the new kind of ‘mass’ advertising, the real ‘Northcliffe Revolution’ in the press occurred, taking the newspaper from its status as an independent private enterprise to its membership of a new kind of capitalist combine. The real basis of the twentieth-century popular press was thus effectively laid.

(vi) 1920–47

Between 1896 and 1920 there had been an expansion of readership and a concentration of ownership. After 1920, the expansion of readership continued, the concentration of ownership appeared in new areas of the press while relaxing a little in others, and, for the first time in the whole history of the press, a decline began in the actual number of newspapers. These positive and negative aspects of expansion are the basic factors within the period to be examined.

Expansion of readership took place in two phases: 1920–37, and 1937–47. In the first phase, the main expansion is in the national daily press, and this was promoted, as is well known, by extraordinary non-journalistic measures, of the kind begun by the Daily Telegraph and rapidly developed by Newnes, Pearson and Northcliffe: the organisation of functions and campaigns, the offering of insurance, and (now particularly developed by Southwood for the Daily Herald) the offering of many kinds of goods with readership. Since all the popular papers vied with each other in these characteristic forms of commercial advertising, the effect was a general expansion in readership rather than the emergence of a single leading newspaper, as had been normal in earlier periods of growth. From a daily total of 5,430,000 in 1920, the national morning papers had reached 8,567,567 in 1930, and 9,903,427 in 1937. In 1920 there had been two papers with a million-plus circulation; in 1930 there were five; in 1937, two above two million and three above a million. The Mail had continued to lead until 1932, but was then passed by the Express and Herald. By the mid-thirties, the expansion had reached into all social classes, though not evenly. There is at this time heavy buying in the income groups above £500 a year, and quite heavy buying in the group between £250 and £500, but in the group between £125 and £250 buying is distinctly less heavy, and in the group below £125 comparatively light. The comparison with Sunday papers is still significant: in 1930 a Sunday total of 14,600,000 against a daily total of 8,567,567; in 1937, 15,700,000 against 9,903,427. It will be noted, however, that the rate of Sunday expansion between 1920 and 1937 is much slower than that of daily expansion: a 20% as against an 80% increase in total sales. Meanwhile in the provincial press, there is no expansion at all, but even a slight decline.

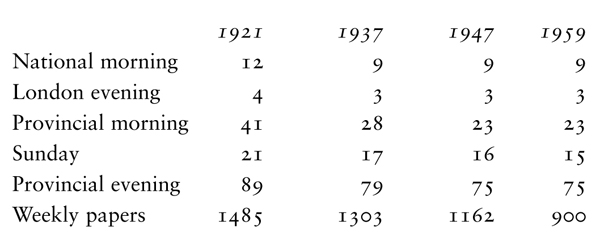

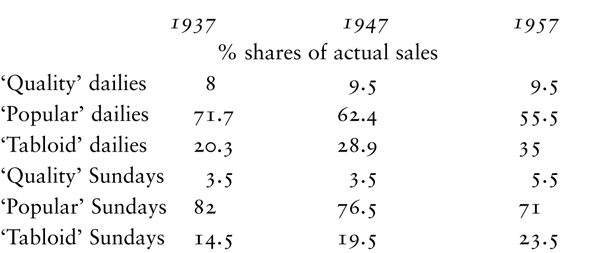

The period had begun with considerable difficulties for the press. Newsprint, which had been £10 a ton in 1914, was at £43 in 1920, and £22 in 1922; by 1935 it was to drop again to £10. In the early years of high costs, several newspapers ceased publication, and the mounting cost of the competition for circulation reinforced this tendency. Between 1921 and 1937, the number of national morning papers declined from 12 to 9, and national Sundays from 14 to 10. Provincial morning papers declined from 41 to 28 in the same period, and provincial evening papers from 89 to 79. Associated with this decline in the provincial field, though not its primary cause, was the extension of combine control into large areas of the provincial press. Chain ownership of provincial morning papers increased from 12.2% in 1921 to 46.35% in 1937, and of provincial evening papers from 7.86 to 43.01%. There was also an increase in combine ownership of the Sunday press, 28.64 to 47.11%, but in the daily national press control by the leading combines became less during this period, falling from 50 to 22%.