4

As Seth’s parents heard the psychologist say “autism spectrum disorder,” they were worried about what the future would hold for them and their son. “Fortunately,” the psychologist continued, “there are some very good programs that have been developed to treat the exact kinds of challenges Seth has.” She handed them a slip of paper with a phone number written on it and encouraged them to call that very afternoon, saying, “They will give you the tools you need to help Seth.” Seth enrolled in a preschool that was designed to help children with ASD that fall. He stayed in this program for 2 years, until he was eligible for kindergarten. His parents asked his teachers what type of program he should be enrolled in next, and were delighted but a little worried by their reply: “Children like Seth can usually function quite well in a regular classroom after this.” While Seth had made rapid progress in preschool and could now talk very well, he still had many difficulties, and his parents knew that his need for special services was far from over. Thus began their long search for therapies, programs, and classes that would help their bright, talkative, but socially challenged son negotiate his course through life.

SO NOW WHAT?

Obtaining a diagnosis may not be the most important outcome of your child’s assessment. Even more critical is what the diagnosis tells you about how to help your child develop the skills needed to be successful in school, with peers, and beyond. The rest of this book covers methods of addressing specific challenges associated with ASD while capitalizing on the strengths associated with high-functioning ASD. This chapter presents an overview of the different treatment options available in many communities and, when known, their relative benefits and risks. As discussed in Chapter 1, the range of outcomes seen in adolescents and adults with ASD is wide. All children make progress with treatment. Some people quickly improve a great deal and their disabilities become less apparent over time. They function well in a variety of different roles and settings typical for their age—college student, employee, roommate, friend, neighbor—with few apparent impairments. Others continue to face significant challenges, but nevertheless are able to live productive and happy lives with some support. In this chapter you’ll learn which currently available treatments seem to maximize the likelihood of the best outcome for your individual child. We hope that as more children are diagnosed and treated early, it will be easier for them to succeed well in adolescence and adulthood.

While treatments for ASD are becoming more available in many communities, you may have to do a good deal of the tracking down and setting up of your child’s therapies yourself. As you’ll realize while reading this chapter, there is a fairly long list of interventions that may help your child. Some of these approaches will benefit some children, but very few (if any) will help all children. Even tried-and-true treatments for common medical illnesses, like aspirin and antibiotics, are not effective for everyone and may even be harmful for some people. ASD and its treatments are no different. Only very rarely are the different treatments described in this chapter offered under one roof, by one agency, clinic, or therapist. This is the bad news that comes with the good news that your child is more mildly affected by ASD. Unlike programs for children with moderate-to-severe ASD, there are fewer comprehensive programs that address all the needs of the higher-functioning child. You will need to find a professional who can help you assess your child’s specific skills and deficits and draw up an individualized treatment plan. There is limited research to indicate which children are most likely to benefit from which therapy—choosing a therapy is based on the clinical recommendations of your evaluator, availability, and your preferences. And then it is necessary to monitor progress and determine whether the therapy is working or whether other options should be explored. You will become an expert in your child’s abilities and disabilities, making decisions about which of the treatments to try and educating teachers, service providers, and others about your child. You will become your child’s best advocate. In some ways, this is a less-than-ideal situation, because you are likely already experiencing a tremendous amount of stress while parenting your special child and supporting and raising a family. But there are no teachers, therapists, or agencies that can be available to your child 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, for the rest of his or her life. You are the consistent thread from one classroom to another, from one intervention to another, from one therapist to another, who manages all the details, remembers all the important facts, and knows what worked and what didn’t. You will be heavily involved in teaching your child how to learn new skills and respond in everyday situations when therapists or teachers are not present. You are a critical ingredient in your child’s life. The rest of this chapter, and this book, will give you the resources, skills, and support to succeed in this role while minimizing the tremendous burden it can represent.

“When Julie was diagnosed with ASD when she was 3, we knew very little about ASD and were unsure where to turn and what to do. Julie was so smart, even precocious, so at first we wondered if the diagnosis was wrong. But her constant repetition of dialogue from Disney videos and difficulties interacting with others fit autism to a tee. So we both took a deep breath and vowed we’d do everything we could to help Julie. It was confusing and daunting at first. The Internet was full of information about ‘miraculous’ and sometimes expensive treatments. It was paralyzing at first. How could we know which treatment would work best for Julie? Which treatments were worth investing our time and money in? Eventually, we found trusted people—both other parents and professionals—who helped guide us through these early months. We’ve decided to concentrate on what we can do to help our daughter make the best of who she is. And the future looks brighter than we could have guessed a year ago. ASD will likely always be a part of Julie’s life. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing. ASD is part of what makes Julie the unique and special person she is.”

TREATMENT OPTIONS IN THE PRESCHOOL YEARS

If you have a preschool child who was recently diagnosed with ASD, you have several treatment options. Some of these have received much media attention, and you may already be aware of them. What you probably don’t know is whether they are as appropriate for your high-functioning child. Research suggests that all children on the autism spectrum, regardless of functional level, benefit from intensive early intervention. In fact, children with ASD who have stronger cognitive and language skills are the most likely to make rapid progress in response to early intervention. Research has now shown that early intervention can actually stimulate brain regions that are responsible for social behavior, leading to rewiring, reorganization, and the formation of new neural connections important for appropriate social behavior and communication. Additionally, your child’s strong cognitive and language skills will help your child develop strategies that can compensate for skills that your child may find difficult to acquire. For example, he can use his strong memory skills to memorize rules and scripts that are useful for social interaction.

Some parents and professionals wonder whether children who are bright, verbal, and relatively more interested in social interaction should receive intensive early intervention. In most cases, such interventions are the best choice for achieving optimal outcomes. Depending on the services available in your own community, this may mean that you will decide to enroll your child in a home- or center-based preschool program specifically designed for children with special needs such as ASD. This investment in intensive early intervention will pay off later and provide the best chance for your child to function in less restrictive or specialized educational classrooms when older.

It is important to understand that your child has the right to inclusion in the least restrictive educational setting in which your child is able to make progress. You, as parents, will have your own opinions about what classroom is best, which may differ from those of the doctors working with your child. What you should know as you choose treatment programs for your child is that multiple intermediate options exist, in addition to the two extremes of a specialized self-contained program versus a regular classroom. For example, some parents enroll their child in a self-contained special education program, but then also have the child attend the neighborhood school for a regular preschool class or for social or extracurricular activities, perhaps with the assistance of an aide. Another option is to administer the early intervention treatments in a regular preschool classroom, rather than at home or in a special education setting. This is a good option if the regular education teacher is flexible and will allow other specialists to participate in the classroom or even use some of the intervention strategies herself. Many parents will feel comfortable starting off with a more intensive early intervention program, delivered at home or in a special classroom setting, when their child is young, to ensure that the child gains the skills necessary to be educated in a regular education classroom by the time kindergarten starts. More important than the setting is that your child receive high-quality intervention that is sensitive to your child’s unique learning style, strengths, and challenges, and that your child is making good progress and thriving well in the setting you have chosen.

Depending on where you live, some of the following interventions may be more popular or more available than others. Currently, these approaches are the most widely accepted and most effective preschool interventions. More information on each of them, as well as other treatment options, can be found in the Resources at the back of the book. Table 3 also compares their features.

Table 3. Treatments for ASD

Applied behavior analysis (ABA)

Ages: Preschool

How and where delivered: Usually but not always at home, by a trained professional team, 20–40 hours a week

Features: One-on-one teaching of basic social, communication, attention, and academic skills, using behavioral principles of positive consequences (rewards) for desirable behavior and negative consequences for undesirable behavior

Strengths and weaknesses: Costly if insurance doesn’t cover, but allows many children with 2 years of treatment to function well in regular school without special support

Early Start Denver Model (ESDM)

Ages: Infancy (12 months) through late preschool age

How and where delivered: At home and school

Features: Uses ABA strategies and also emphasizes play, positive social relationships, child-preferred activities, sharing emotions with others

Strengths and weaknesses: Studies demonstrate effectiveness in increasing language, IQ, and social skills

Treatment and Education of Autistic and related Communication handicapped Children (TEACCH)

Ages: Preschool to adulthood

How and where delivered: Mainly at school, with home supplementation possible, by teachers and parents

Features: Visual structure and organization of environment and learning materials using visual, mechanical, and memory strengths to teach language, imitation, social, and cognitive skills; one-on-one or in groups

Strengths and weaknesses: Outcome less well studied than ABA and ESDM

Social skills groups

Ages: Preschool through adulthood

How and where delivered: Therapist’s office, clinic, or school, led by therapist or teacher

Features: Development of conversational skills, body language, perspective taking, reading of others’ emotions, regulating emotions, social problem-solving skills such as dealing with being teased or left out

Strengths and weaknesses: Teaches skills and provides practice with peers; provides tools that translate to home training; can be used through adulthood

Educational support

Ages: Preschool through college

How and where delivered: School

Features: Accommodations to and modifications of environment and academic goals

Strengths and weaknesses: Negotiable with schools; adaptable to individual needs; mandated by federal laws

Pragmatic language–communication therapy

Ages: Preschool through adulthood

How and where delivered: Group setting or pairs of children, provided by speech–language pathologist

Features: Training in pragmatics of language: social communication, abstract or complex language concepts

Strengths and weaknesses: Beneficial when social skills group is unavailable or when child has more communication problems

Functional behavior analysis

Ages: Preschool through adulthood

How and where delivered: School, home, and other settings, by any adult in charge

Features: Examination of function of disruptive or problem behaviors; provision of more appropriate ways to communicate

Strengths and weaknesses: Reduces behavior problems and increases communication skills

Medication

Ages: All ages

How and where delivered: Prescribed by a medical doctor, such as a pediatrician, child psychiatrist, or neurologist; given usually daily by parents at home

Features: Alters levels of brain chemicals that are affecting child’s behavior

Strengths and weaknesses: May be helpful for attention or activity level problems, depression, anxiety, anger, but does not treat social or communication symptoms of ASD

Sensory integration therapy

Ages: Preschool, childhood

How and where delivered: Office of an occupational therapist, possibly with home exercises provided

Features: Decreases sensory sensitivities, develops coping skills and tolerance for new sensations

Strengths and weaknesses: Little research to determine effectiveness

Individual psychotherapy

Ages: Adolescence through adulthood

How and where delivered: Office of a psychotherapist, potentially with “trips” into community

Features: Explores moods and emotional states; develops self-awareness and self-acceptance; takes a cognitive-behavioral approach

Strengths and weaknesses: Best for individuals with good insight; may not generalize to group settings; needs to be as directive and concrete as possible

Autism Speaks (www.autismspeaks.org) provides a comprehensive list of various early intervention approaches, along with videotapes that demonstrate each one. This will help you decide which approach might be the best fit for your child. Although some of these treatments have more scientific evidence to back them up than others, there have been very few studies that have compared two different treatments to see which is the more effective. Furthermore, all studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of the available early intervention models have found that some children respond dramatically and quickly and others make slower progress. In other words, there is no “one-approach-fits-all” solution. Depending on your child’s unique strengths, unique challenges, and unique learning style, as well as the availability of treatments (and associated costs) in your community, you will need to decide for yourself what works best. Then, by monitoring whether your child is making progress and thriving in the classroom or treatment model you chose, you will be able to determine whether changes or tweaks to the program are needed. These changes and tweaks are inevitable because the needs of your child will change over time.

Although research has not clarified the optimal number of hours of treatment a child should receive, generally at least 25 hours of structured intervention each week are recommended during the preschool years. This can include a range of treatments, such as participation in a regular or special preschool program, speech–language therapy, and occupational therapy, in addition to early behavioral intervention. Parents’ use of intervention strategies at home counts as well. The point here is that typically developing children have many opportunities for learning throughout the day, and we want to ensure that children with ASD are also having many learning opportunities. How many hours and types of services should be delivered often is based on the child’s readiness, rate of progress, and response to treatment and the child’s need for rest and other family activities, as well as community standards and the range of local services available. Because of the intensity of the program, school systems may not have an autism-specific early intervention program in place. If you and your doctors believe early intensive behavioral intervention is the appropriate intervention, you may have to work with your local school district to develop the program for your child. Here are descriptions of a few of the most commonly used early intervention approaches:

Applied Behavior Analysis

In the 1960s, Dr. Ivar Lovaas as well as other psychologists began using a method called applied behavior analysis (ABA). Lovaas then went on to develop a model of early intervention that used a teaching method called discrete trial training, sometimes called the “Lovaas method.” The Lovaas/ABA method uses general principles of behavioral therapy to build the skills that children with ASD lack, such as language, play, self-help, social, academic, and attentional skills. In addition, this model incorporates strategies to minimize the unusual and repetitive behaviors of autism spectrum disorder.

In the Lovaas model, teaching is initially done one-on-one and is highly individualized, with specific treatment goals chosen based on the child’s abilities and challenges. Once basic communication, social, and attention skills are mastered, the child is gradually introduced into a group learning situation. A member of the treatment team at first accompanies the child to the classroom to facilitate transfer of skills between the two settings. The aide, or “shadow,” is eventually faded from the class, and the child is then fully integrated into the regular school program. This process may take 2 or more years to complete, and many children are able to attend a general classroom by kindergarten.

Spencer’s parents heard about a promising educational program based on ABA principles from an acquaintance whose son also had ASD. They were referred to a local psychologist trained in the use of ABA, who did some testing with Spencer to determine his individual needs. After concluding that Spencer would likely benefit from early intensive behavioral intervention, the psychologist recommended that a home program consisting of approximately a dozen goals be set up. Since Spencer was bright and already had some useful skills (talking in simple sentences, sitting in a chair, and attending), the initial goals were primarily academic: identifying colors, shapes, numbers, and letters; stating the functions of objects; answering questions (“What is your name?”; “How old are you?”); identifying environmental sounds; imitating two-step sequences; and drawing shapes. Communication and social goals were also incorporated, such as how to have a brief conversation and greet others. Therapists came into his home daily to work with him, and Spencer progressed rapidly. Within only a few months, he had mastered all of his initial goals. Spencer’s parents also noticed changes in his behavior: his eye contact was better, he talked in longer sentences, and he was more cooperative at home and in his church nursery school. As Spencer progressed, new goals were added to increase his pretend play skills, his ability to ask questions and make comments, and his ability to take turns and follow rules of simple games. Over the following year, Spencer continued to improve, so his intervention team decided that he was ready for some integration into a regular preschool to work on his skills with peers. He began attending 4 hours a week, with an aide helping him. Time in the preschool was gradually increased to 15 hours. By the time he was 5, his parents felt ready to enroll Spencer in a regular kindergarten class without any special assistance. He still had a few quirks, but he seemed as bright and ready for kindergarten as any other child in their neighborhood. They finally breathed a sigh of relief when Spencer’s kindergarten teacher told them what a delightful son they had. She commented that he was academically advanced and chuckled about his habit of asking all the adults what their license plate number was.

Research has demonstrated that many children, especially those who are high functioning, who begin treatment early and receive 2 years of ABA-based treatment are able to enter and function well in typical first-grade classrooms, without special support. In addition, Lovaas’s study found that the cognitive abilities of treated children (as measured by standardized tests) were far higher than those of untreated children with ASD. So it’s no surprise that ABA-based interventions are very popular in many areas. An obvious drawback, however, is the expense and effort of one-on-one treatment. Almost none of the children that Lovaas’s team studied who had received only 10 hours a week or less of ABA model treatment achieved the same success as the kids who had 40 hours a week of treatment. Information about early intervention providers using ABA methods in your region is available from the Autism Speaks website (www.autismspeaks.org/resource-guide/by-state). The national organization called FEAT (Families for Early Autism Treatment) also maintains a web page that lists ABA providers by state (www.feat.org).

Early Start Denver Model

Another option for early intervention is the Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) developed by Drs. Sally Rogers and Geraldine Dawson. ESDM can be used with children as young as 12 months of age. This approach incorporates the principles of ABA but also emphasizes the parent–child relationship as a foundation for learning. Teaching occurs in the context of play-based activities in which language, communication, social behaviors, and cognitive skills are taught. Like traditional ABA, ESDM has been validated in research studies and shown to lead to increases in cognitive, language, and social skills. ESDM can also be delivered by parents at home. In a study published in 2010, it was found that children who received the ESDM intervention for 15 hours per week for 2 years made significant gains in IQ, language, adaptive behavior, and social skills. The manual is available in many languages, including Spanish.

Strategies based on the ESDM model that parents can use to promote language, social interaction, and learning are described in the book An Early Start for Your Child with Autism, by Sally Rogers, Geraldine Dawson, and Laurie Vismara. You can use these strategies in combination with treatment provided by a therapist or even begin them while you are waiting to be enrolled in an intervention program. These are strategies that promote communication, social engagement, and learning that can be used during your regularly daily activities with your child, such as during meals, bathtime, and play activities.

TEACCH

Another treatment approach in use in some parts of the United States and around the world is the TEACCH model (this acronym stands for the Treatment and Education of Autistic and related Communication-handicapped CHildren program). This treatment program was developed in the 1960s by Dr. Eric Schopler, a psychologist at the University of North Carolina. A cornerstone of the TEACCH educational approach is visual structure and organization of the environment and learning materials. As discussed in Chapter 2, many children with ASD have difficulty with abstract, language-based tasks and instructional techniques but have relatively strong visual–spatial capacities. The TEACCH program capitalizes on the visual, mechanical, and rote memory strengths of many children with ASD, using them to develop more challenging skills, such as language, imitation, cognitive, and social skills.

TEACCH programs typically structure academic, social, communication, and imitation tasks for the child so that what is expected and how to complete it are visually apparent. Visual schedules, consisting of pictures and words that show daily events in order of occurrence, help the child anticipate what is to come or the work that needs to be done during a teaching session. The child can then, on her own, without teacher prompts, “predict the future.” Many children with ASD tend to tantrum or become upset when things in their environment change. They cling to the familiar, not necessarily because they enjoy what they are doing but because they know what they are doing and don’t know what comes next. Introduction of a picture schedule can significantly reduce anxiety, frustration, and tantrums, in addition to promoting more independent functioning. See the Resources for information on how to order materials to be used in making visual schedules. While outcomes of children participating in TEACCH interventions have not been examined as closely as outcomes for other treatments discussed so far in the chapter, parents and professionals often choose to combine elements of the TEACCH model (such as visual schedules) with elements of other intervention programs, integrating treatments to best meet the needs of an individual child.

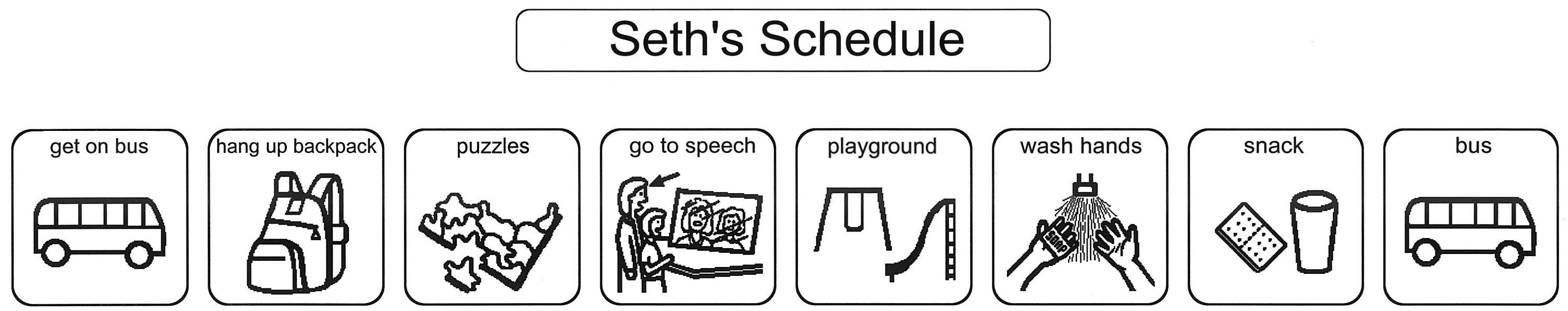

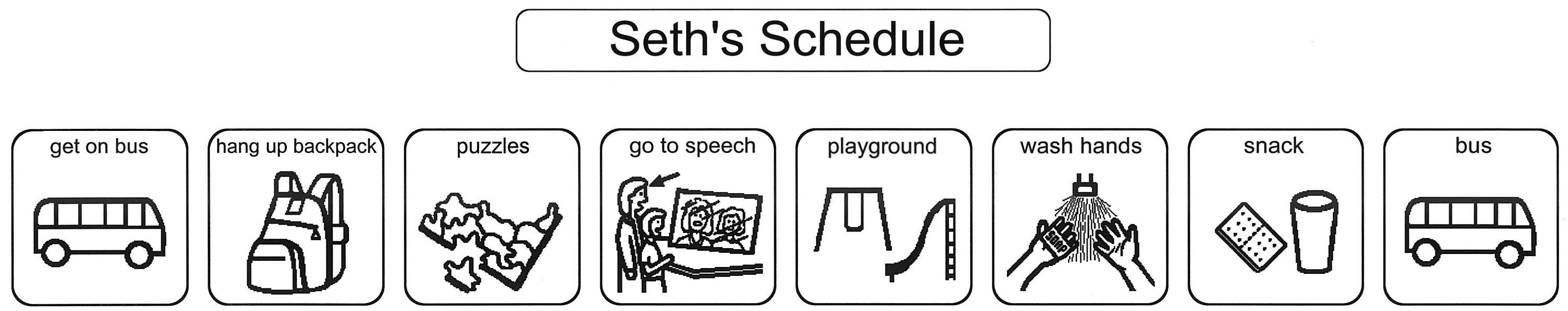

Seth’s preschool teachers implemented a schedule for him after seeing how anxious and upset he became when there were changes to his school day and how much he thrived on routines. When Seth memorized what was coming up (for example, lunch immediately follows a trip to the bathroom and washing hands), he was eager to move on to the next activity. However, even minor deviations in the routine, such as staying indoors on a rainy day, elicited shrieks of dismay from Seth, followed by many minutes of lying on the floor, kicking at anyone who approached. His teachers decided to begin using a schedule for Seth, which showed in pictures each of the major events of his day (see Figure 2). When something wasn’t going to take place as usual, they used the universal “no” sign (red circle with a slash through it) to indicate the change. They were amazed when Seth’s tantrums quickly stopped. He was even able to take it in stride when his speech therapy was canceled due to his therapist’s illness, as long as his teacher indicated the change on the schedule.

FIGURE 2. Visual schedules can be used to decrease anxiety and promote independent functioning. The picture communication symbols used in Seth’s schedule are ©1981/2014 by DynaVox Mayer-Johnson LLC. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. Used with permission.

These are a few of the most commonly used approaches to early intervention. Additional approaches are described on the Autism Speaks website (www.autismspeaks.org). The doctor who diagnosed your child will probably also have a list of community treatment referrals available, as may your community mental health center or the psychiatry departments of local hospitals. Federal law requires that every child who has delays in development be offered services, which are referred to as “Part C—Birth to Three Services” for children below 3 years of age and “Part B—Preschool Services.” Your pediatrician should provide you with a contact number so you can find and obtain these services, at no cost.

As you consider which option is best for your child, keep in mind that, at present, however, no studies have directly compared the different treatment approaches just described. Thus, which programs have the most benefit for which children is not certain. We recommend that you find the options available in your community, visit and observe the therapists or schools offering them, discuss them with your doctor, and weigh the costs and benefits to both your child and your family before making treatment decisions.

INTERVENTIONS FOR PRESCHOOL AND BEYOND

If the preschool program your child attends is intensive and comprehensive, then you may not have the time or the need for the following treatments until he is older. But what if you missed the preschool years and the interventions just discussed? What if your child was diagnosed after age 5? Or what if, like Seth’s parents, you’ve found a very effective preschool program and want to continue with some interventions upon entering grade school? All is not lost! A wide variety of helpful interventions are available for older children. As mentioned earlier, they may not always be easy to find or readily offered to your child, but they are out there.

Some of these interventions use the same principles as the preschool programs just reviewed, so your child may still benefit from the use of behavioral or visual techniques, at a level appropriate for her age and developmental level. The two most common needs of children with higher-functioning ASD are social skills training and educational assistance. There is a wide variety of different interventions for each, so we have devoted a separate chapter to each of these topics and will mention them only briefly here.

Treatment needs vary widely from child to child, but we have listed the following interventions roughly in order from the most to the least commonly needed.

Social Interventions

By now you certainly know that difficulties in the social realm are among the most prominent of the problems faced by your child. Naturally, therefore, they are an important domain for intervention. The many options for working on social behavior are discussed in more detail in Chapter 8. Social skills groups are one option that can be a particularly helpful resource. These groups focus explicitly on the social behaviors that other children seem to learn naturally. We can’t take for granted that children with ASD will absorb and imitate typical social behaviors just by being around others who perform them naturally (siblings, parents, peers). Social behavior is best taught in a social setting, and social skills groups provide that setting, along with the structure needed to teach these complex skills. Some common topics that such groups address include appropriate body language and eye contact, reading the emotions of others, and taking others’ perspectives. Conversational skills and other behaviors important to interactions, such as introducing oneself, joining a group, giving compliments, negotiating, sharing, and taking turns, are a typical focus of social skills groups. Additionally, they usually address social problem-solving skills, such as handling teasing and being told “no,” dealing with being left out, and regulating and expressing emotions in age-appropriate ways. A benefit of this approach is that your child has the chance to try out these skills in a safe situation, hopefully providing the opportunity to have social “fun” and increase the child’s motivation to improve these skills. Research has shown that social skills interventions are effective for improving children’s abilities to play, make friends, handle teasing, and manage a wide range of social situations. Often these interventions take place in a group setting and are offered at school and at local clinics. Speech–language therapists sometimes offer social skills training.

A related type of intervention relies on video modeling. Research has shown that this approach is effective for teaching social skills to children with ASD. The approaches use video recording to display a model of the targeted behavior or social skill. Typically, it involves recording a person modeling the target skills. The child views the video and then practices the targeted behavior. This approach takes advantage of the strong visual skills of many children with ASD. Video modeling can be used while working one-on-one with a child or in a group setting as part of social skills training.

Your area may not have a social skills group exclusively for children with ASD, but there may well be one for children with attentional or other behavior problems. The child or adolescent with ASD often benefits from the opportunity to meet other kids with ASD who share similar interests, personality styles, temperaments, and challenges. But as long as the group addresses many of the issues listed above and you feel that there is a good fit between the therapeutic goals of the group and your child’s needs, it is not necessary that all or even most of the participants have ASD. You should also check with your school district, since social skills groups may be offered through schools.

There are also several things you can do around your home or community to improve your child’s social behavior and provide opportunities to practice social skills:

•Write out “scripts” that help your child know what to do and say in certain social situations, such as answering the telephone or ordering food in a restaurant.

•Videotape your child having a conversation with someone and then watch it together, pointing out both things he or she did well and things that need improvement.

•Videotape others (perhaps siblings) to provide a model of age-appropriate conversation.

•Enroll your child in groups that revolve around his or her special interests so that he or she has an opportunity to meet like-minded others.

•Invite peers to the home to play and then carefully monitor the interactions and provide structure and support to help your child learn turn taking, sharing, compromising, and other skills.

•Set aside 15 minutes each day in which you converse with your child, uninterrupted by siblings, household chores, or the telephone, about a prearranged set of topics (school, plans for the weekend, jokes). You might furnish the topics to your child beforehand or have them written down to encourage sticking to the topics and discourage drifting to your child’s special interests. If needed, you might provide visual cues that encourage turn taking (perhaps an arrow that can be pointed toward the person whose turn it is to speak) and discourage verbosity (for example, a stop sign that can be held up to indicate that your child is going on too long).

These and many other techniques used in both clinic and home settings to improve social behavior are described in more detail in Chapter 8.

Educational Assistance

The second area of typical need is educational support. Despite average or better intelligence, many students with ASD have difficulty in school or don’t achieve at the level expected. They have difficulty organizing and regulating themselves in class and managing time, often resulting in failure to complete work during school and many extra hours of homework. They may have trouble planning ahead, setting appropriate goals and subgoals, estimating the time it takes to complete tasks, and remembering to bring home what is needed to complete homework assignments. These problems with self-regulation, goal selection, and attention may result in spells of daydreaming or absorption in inner thoughts. Inflexibility and rigid problem-solving strategies also affect school performance. Finally, children with ASD are often not motivated by the same kinds of rewards that other children are. They do not particularly care that their teachers or parents will be displeased if they leave work unfinished or get poor grades. They may have little intrinsic motivation to work on topics that aren’t related to things that interest them. They may care little if they get detentions or have to stay in from recess; for a child stressed by social interactions, these punishments might actually be rewarding! Therefore, it can be difficult to inspire the child with ASD to do schoolwork, even when her intellectual abilities are strong.

For these reasons, most children with ASD will need some classroom accommodations and modifications to succeed in school. There may also need to be some adjustment of academic goals, perhaps placing more or less emphasis on certain subjects, making work more or less challenging than that of classmates, or making schoolwork more directly functional. For example, you may want more emphasis placed on vocational and daily living skills than on a traditional academic curriculum. It may be necessary to start working on these skills earlier than would be typical for other children to promote your child’s ability to live independently and function in a work setting as an adult. Year-round schools or academic summer programs are often helpful, because change is difficult for most children with ASD and they can regress in behavior and academic skills over the long summer vacation.

In Chapter 7, we describe in detail the kinds of educational supports and services that appear most useful for students with ASD. Many of the accommodations we suggest capitalize on your child’s good visual skills and memory, using these strengths to make up for weaknesses in organization, planning, attention, and flexibility. The most essential part of educational programming is adapting the curriculum to your child’s individual problems and unique abilities (more on this topic in Chapter 5 as well). At this point we will say only that, in addition to finding social skills training for your child, you will probably want to contact your school district to discuss the most appropriate ways to deliver educational support to your child.

Pragmatic Language–Communication Therapy

Most individuals with milder ASD have relatively well-developed language abilities. They can speak fluently, in full sentences, with few or no grammatical errors. Yet they most likely exhibit some difficulty using language in a social context to exchange ideas and information with others. They usually have trouble with abstract or complex language concepts. When what we say isn’t exactly what we mean (such as when we are sarcastic, joking, or using metaphors or other figures of speech), the child with ASD may misunderstand. All these difficulties are collectively referred to as deficits in the “pragmatics” of language. There are rules that underlie conversation that the rest of us learn naturally and know implicitly. These include taking turns, providing enough information to be clear without being verbose, and contributing relevant information. We know how to choose appropriate topics, how to stay on a topic, and how to switch to a new subject. We know how to “read” other people and can adjust our communication to the needs of the person with whom we are speaking. If someone seems bored, we try to liven up our conversation or change topics. If someone seems confused, we try to figure out why and provide clarification. We speak differently to a child than to an authority figure or a peer. We understand how intonation or an accompanying facial expression can change the meaning of what we say. However, children with ASD may not know these rules and often have to be taught them explicitly.

Much of this can be addressed in a good social skills group. (After all, how do we separate communication from social skills? The two go hand-in-hand.) But if no such group is available in your area or if the group does not address such conversational skills, you may want to explore whether some form of speech–language therapy would be helpful for your child. Ask around to find a speech–language pathologist experienced in working with people with ASD. Find out whether the person offers “pragmatic language” training or therapy in conversational skills. Often such therapy is offered in a group setting or with at least two children present. These skills are not well remediated in isolation, with just a therapist and your child present. Most children with ASD perform well in such structured situations, where the demands are lower and the conversational partner is forgiving. These skills need to be practiced with other children, with the guidance of a knowledgeable therapist who can provide a supportive atmosphere and explicit feedback about the strengths and weaknesses of the child’s communication style.

Behavioral Interventions to Address Challenging Behaviors

Children and adolescents with ASD can demonstrate some unusual and problematic behaviors that require specific management. Your child may at times have temper outbursts, meltdowns, or tantrums that seem out of proportion to the incident (or are unpredictable, with no apparent trigger). Or maybe your child is impulsive and distractible, shouting out in class, grabbing things from other people, or having trouble sitting and focusing on work. Perhaps your child is very rigid about routines, the order in which things are done, or where favorite objects are placed. One young boy named Mark insisted that boxes of cereal be eaten in order by weight—that is, if the Cheerios box weighed more than the Rice Krispies box, it had to be completely consumed before the next box of cereal could be opened. Josh, a 15-year-old with ASD, knows a lot about presidents and likes to be “quizzed” about presidential facts—if, however, he gets an answer wrong, he insists that the person quizzing him start over with the first question and repeat every single one in order, until he gets to the question he got wrong. This is accompanied by a lot of shouting and crying, as Josh becomes very distressed when he is corrected. All of these issues can be dealt with by using behavioral methods, treatments that rely on principles of applied behavior analysis to teach more appropriate behavior. Behavioral strategies can be classified in two broad categories, those that modify behavior by changing what precedes the behavior and those that modify behavior by changing the consequences of the behavior.

Changing What Precedes the Behavior

The first approach can be thought of as a preventive approach. It is meant to stop behavior problems before they start, by changing things in the environment that are known to cause disruption, anxiety, or other stress to the child with ASD. Many of the strategies described in Chapter 7 regarding classroom accommodations fall into this category. We encourage educators to teach the child using visual methods and to provide as much structure and organization as possible. This capitalization on the strengths and minimization of the weaknesses known to be associated with ASD is just one example of the preventive approach to behavior management. Other examples include being sure that your child is well rested and not hungry, making sure that the side effects of medications are not causing behavior problems, and using visual schedules to increase predictability and consistency for your child. All these “interventions” are intended to decrease stress on your child and increase his feelings of control, and thus may be effective in reducing behavior problems.

Changing the Consequences of Behavior

The second strategy, providing specific consequences to mold appropriate behavior, derives from operant conditioning theory, made famous by Dr. B. F. Skinner. Most living things, from the simplest invertebrates to humans, from infants to adults, and from those with ASD to those without, can change their behavior based on these learning principles. Specifically, if a behavior is reinforced, that is, followed by something good, then it increases in frequency, while if it is punished, ignored, or followed by any other negative outcome, it decreases in frequency. We can use these principles to change the behavior of children with ASD (in fact, ABA therapy, described above, is based on these very principles). If there are things we want to teach, we reinforce them. If there are behaviors we want to go away, we provide negative consequences for them. Most people with ASD learn well when provided with explicit rules. Reward systems can be set up that make it worth the child’s while to follow the rules. Obviously, rewards that are effective incentives for children with ASD are likely to be those linked with the child’s particular area of intense interest, such as extra time looking up dragonflies on the Internet, a trip to the zoo exclusively to see the insect displays, and the like. But your child may appreciate other, more generic rewards, just like other kids, whether they are favorite dinners or special privileges such as staying up later than usual. Experiment, just like you would with your “typical” children. But before you come up with either rewards or punishments, be sure to explore preventive strategies, because some problem behaviors can be eliminated altogether through changes in the environment and other forms of structure. If this does not eliminate the problem or result in the desired behavior, an operant approach may be successful.

Jenna is a young girl with ASD who had resisted sleeping alone since infancy. She would cry and tantrum when put down in her own bed, but would easily fall asleep in her parents’ bed. They would then carry her back to her own bed. However, later in the night she would awaken, wander through the house, line up favorite items, help herself to food from the refrigerator, and eventually climb back into her parents’ bed to sleep for the rest of the night. When her parents woke one night to find Jenna sitting up in between them with a library book and a pair of scissors, they decided to seek help. They first went to their doctor to explore whether there might be some physical reason, like seizures, that could be contributing to Jenna’s night waking. After ruling this out, as well as making some changes in her diet (eliminating food and drinks with any caffeine and decreasing liquid intake in the evenings) that did not change her sleep, they were referred to a psychologist.

A behavioral program was set up that included clear rules for Jenna to follow and clear rewards for doing so. A bedtime routine was established that consisted of putting on pajamas, brushing teeth, using the toilet, reading two books, saying prayers, turning out the light, kisses and hugs, closing the door halfway, and then parents leaving the room. A photo of Jenna engaging in each of these steps was taken and placed in order on a piece of cardboard that was then taped next to her bed. The sentence JENNA, STAY IN YOUR BED was written on the bottom of the chart. Jenna, with her parents’ help, made a list of all the things she would like to earn for staying in bed, including favorite snacks (which were withheld at other times of the day), small trinkets and toys, special activities with Mom and Dad (making cookies, going on a walk around the neighborhood, playing a game), access to favorite videos, and so forth. Each was written on a piece of paper and then put in a box covered with question marks.

Jenna was given a progressive schedule for earning these rewards, which she accessed by pulling a slip of paper from the “mystery” box. For the first week, she could earn a reward just by cooperatively following the beginning parts of the bedtime routine schedule. In the second week, she could earn a reward by staying in bed without crying for 1 minute; she was then permitted to sleep in her parents’ bed as usual. This time was gradually lengthened, and Jenna could earn the reward only by staying in bed for longer and longer periods of time. Eventually she began to fall asleep while lying in her bed; then the required behavior for the reward became staying in bed throughout the night.

While it took many weeks for Jenna to reach the eventual goal, this procedure was successful in gradually shaping her sleep patterns so that they conformed with the behavior desired by her parents. Jenna greatly looked forward to her rewards and seemed to be highly motivated by the mystery involved in not knowing exactly what she would earn. Jenna’s parents gradually lengthened the interval between the behavior and the rewards (for example, she needed to sleep in her own bed each night for a week to earn one) until Jenna seemed to have forgotten all about the rewards and had firmly established the new behavior.

The plan to help Jenna sleep in her own bed has several important ingredients to highlight. Her parents first explored possible causes of the problem, such as seizures and caffeine intake, and made environmental changes. Then they established a behavioral plan that had clear, predictable rules that were provided to Jenna in a visual format. They made sure that the rewards were actually reinforcing to Jenna by having her choose them. The requirements for reinforcement were at first set very low, so that Jenna experienced immediate success. There was a gradual shaping of behavior and a gradual fading of rewards, so that Jenna had to work harder over time to earn reinforcement, and expectations were slowly made more age-appropriate.

If necessary, negative consequences can be added to such a behavioral plan. Jenna’s parents did not find it necessary to do this, but they could have added another component to the plan indicating what would happen if Jenna did not achieve the specified goal. For example, in addition to not earning the desired reward, she might have lost some small privilege if she got out of bed (5 minutes’ less television the next evening). We talk more about methods for dealing with challenging behavior in Chapter 6.

Methods like this can also be used to reduce obsessive or repetitive behavior. The key ingredients to all such plans include exploring contributing factors in the environment, setting up explicit rules and consequences, consistently adhering to them, and increasing demands in a stepwise fashion so that change is introduced gradually. Dr. Patricia Howlin, a British psychologist who has worked with people with ASD for many years, described using these principles to gradually decrease a young boy’s obsession with “Thomas the Tank Engine” trains. A picture calendar was made that showed when access to the trains was allowed. Less popular “Thomas” activities were substituted for more preferred ones (such as reading a “Thomas” book rather than watching a video). Engaging in alternate activities was strongly rewarded as reinforcement for “Thomas”-related activities was withdrawn.

Sometimes it is not enough to simply provide consequences for behavior and expect it to change. If the behavior serves a very important purpose, then it may persist no matter how many rewards or punishments are introduced. Let’s say, for example, that a child continually interrupts and yells out comments and repetitive questions during class. If the child needs more attention from her teacher and is obtaining it by yelling and interrupting, then the behavior will be very hard to change until an equally powerful alternative is given to the child to obtain the desired attention. If the child is given a hand gesture or written sign that she can use instead, and the teacher learns to consistently respond to the signal, then the interrupting behavior may go away without any need for a behavioral system of rewards. Likewise, if a child gets agitated and begins hitting himself during class, an examination of the function of the behavior may indicate that the child is trying to communicate that a task is too difficult. If an alternative way of expressing this frustration and desire to change activities is found (for example, giving the teacher a card with a picture of a stop sign on it), the self-hitting may stop abruptly. Problem behaviors can serve many functions; in addition to getting attention or escaping from an unpleasant task, they might indicate a need for help, a need to obtain a desired object, or boredom. Chapter 6 contains advice on puzzling through the possible messages your child is trying to convey with problematic behavior. Finding alternate ways to communicate these messages and ultimately to solve the problems behind them is at the heart of this type of behavioral intervention, called functional behavior analysis, also discussed further in Chapter 6. Psychologists and educators use a variety of assessment tools to discover the functions of behavior and then change them. If your child is having such problems, ask a behaviorally oriented therapist about such strategies.

Spotting and Heading Off Trouble

Another approach to managing difficult behavior is to learn the warning signs that indicate impending trouble and then distract the child, remove the child from the situation, or provide the child with other incompatible activities for the behavior. Some children show clear signs that they are becoming agitated, aggressive, or anxious. They do not explode out of the blue, but gradually escalate, first appearing worried or nervous, then muttering under their breath, then pacing and flapping their hands, and finally having a full-blown outburst complete with lashing out at others, destroying things, and being verbally abusive. A plan can be set up whereby the child is removed from the threatening situation and taken to a safe place. This might be a room in which he or she can pace, talk, or rant privately; a place with a couch to lie on while listening to soothing music; or a therapist or teacher who can guide the child through relaxation exercises (deep breathing, counting to 10, visualizing alternatives, and so on—see Chapter 8). It is important to engage in a proactive rather than a reactive way, lest a child be implicitly taught that acting out earns these potentially reinforcing activities.

Self-Monitoring and Reinforcing for Teens and Adults

Finally, some individuals with ASD, particularly adolescents and adults, can be taught to monitor their own behavior and reinforce themselves, thereby learning self-regulation and self-management techniques. Such systems are best set up by experienced clinicians. The essential ingredients are teaching the person to recognize the behavior that needs to be increased or decreased; training the person, often using videotapes, to reliably identify instances of occurrence or nonoccurrence of the behavior; and then regularly monitoring the behavior.

As an example, let’s return to the interrupting behavior discussed above. A videotape of the child in the classroom could be made. Then the teacher or parent would sit down with the child and the videotape and point out when interrupting was occurring and when appropriate hand raising and other behaviors were present instead. The child would then be trained to reliably recognize the interrupting behavior. Once she was able to correctly say, “Yes, I was interrupting there” or “No, that was not interrupting” about 80% of the time when watching the video, she would begin the self-monitoring phase. An index card would be taped to her desk; on it would be two columns, one labeled “Interrupting” and the other “Not interrupting.” A watch with a soft alarm would be provided that would go off every few minutes. Whenever the alarm sounded, the child would have to place a check mark in one column or the other. By so doing, she would become increasingly aware of the interrupting behavior.

This recognition and monitoring of the behavior, in and of itself, is sometimes enough to alter the problem. Often several of the approaches described in this section need to be used in tandem. Changes need to be made in the environment, rules and rewards need to be set, alternative behaviors must be taught, and then the child can learn to monitor the behavior herself.

Consulting a Behavioral Specialist

While the best behavioral management plans seem like little more than “common sense” to many parents, it is often wise to create and monitor such plans with the help of a behavioral specialist trained in such techniques. Small oversights can unintentionally throw off the whole system. Children may be resistant to the plan parents try to set up, so it can be helpful to have a third party negotiate the terms of the “contract.” Gradual fading of the reinforcement system can be difficult to manage, and assistance in determining the most appropriate pace at which to decrease the rewards is often helpful. Determining whether negative consequences should be added is best left to a professional. It is ideal if data are collected to indicate how successful the program is, when goals should be changed or added, and when new methods should be tried. With professional assistance, behavioral programs can be highly effective in changing some of the behaviors of people with ASD and alleviating much individual and family distress.

Medication

The use of medications to treat people with ASD has increased in recent years. Studies suggest that about half of all children with ASD in the United States have been prescribed a psychoactive medication, and that medication usage increases with age. Research studies have shown that levels of certain brain chemicals (neurotransmitters) are different in people with ASD, sometimes higher than they should be and sometimes lower. Although there are no medications that can reduce the primary symptoms of autism, such as difficulties in communication, appropriate use of medication can often increase the quality of life for both the child and the family. Medications can improve the child’s ability to benefit from other forms of treatment and relieve significant distress for the affected person and those around her. For example, appropriate medical management of inattention and hyperactivity can help a child focus better at school and thus enhance the positive effects of the educational help provided. Similarly, easing social anxiety or reducing negative feelings about the self through medication can permit someone with ASD to participate in and benefit from a social skills group.

A wide range of medications have been used for ASD over the years. However, as yet no medication that reliably alters the core social and communication deficits of ASD in clinically meaningful ways has been found. The drugs that are commonly used with the ASD population address other symptoms and comorbid conditions, such as attention and activity level problems, depression, anxiety, aggression, repetitive thoughts or behaviors, sleep difficulties, tics, and seizures. The most commonly prescribed medications for those with ASD are stimulants such as Ritalin, Dexedrine, and Adderall; newer “atypical neuroleptics,” such as Risperdal and Abilify; and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as Prozac, Zoloft, and Paxil. Note, however, that the evidence for the effectiveness of SSRIs for helping children with ASD is weak. These medications might help in individual cases, however.

The SSRIs are thought to work by increasing levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin in the brain, while stimulants and atypical neuroleptics act primarily on a different neurotransmitter, called dopamine, and block its function or decrease its level in the brain. Stimulants are the treatment of choice for attention and activity level problems and appear to work as well with children with ASD who have these disturbances as they do in children with attention deficit disorders alone. Risperdal and Abilify are medications first used for psychotic conditions, such as schizophrenia, but now found to be useful for the irritability, aggression, and explosive or unpredictable behavior sometimes seen in individuals with ASD. A study found that these types of medications are even more effective if they are combined with behavioral intervention to address behavioral challenges, such as tantrums and aggression.

How effective are these medications in treating ASD? To answer that question, we will digress a bit to explain the process by which we evaluate whether a therapy (any therapy—medical, behavioral, psychological) actually works. An obvious strategy would be to give people with ASD a medication and test them beforehand and afterward to see what the effect was. But more careful examination points out a few problems with this approach. Perhaps the symptoms would have gotten better on their own (for example, as the child got older) and the improvement had nothing to do with the drug. For this reason, therapy studies must use a control sample, which is a group of individuals very similar to those given the treatment—they must have the same diagnosis, the same level of functioning, be of similar ages, and so on—who differ only in not receiving the treatment.

It is well known among doctors that many patients improve after being given a medically neutral or inactive substance (a disguised sugar pill or harmless salt solution), called a placebo, if they believe that it has therapeutic powers. This improvement is known as the placebo effect and is thought to reflect the powers of hope and positive thinking as well as the more general effects of receiving attention from a doctor. So it is important that medications tried with your child have been shown to be more effective than a placebo. Previous studies have demonstrated that about one-third of people show clear improvement from a placebo. So we would want to know that a specific drug helps more than 30% of those who try it. Otherwise, why not spare the expense and potential side effects of the drug and just use the sugar pill? This can be tested in a research study in which the control group, rather than being untreated, is given a placebo instead.

The best studies include random assignment of individuals to the medication and placebo conditions and a lack of awareness on the parts of everyone involved in the study regarding which individuals are given which pill. Random assignment helps make sure that there are no consistent differences between the people getting placebo and those getting the medication that might account for differences in response. For example, if the first people to indicate interest in the study were assigned to the medication group, they might be more motivated to follow the requirements of the study or more hopeful of improvement, which could bias the results of the study. Conversely, if the first people to contact the researchers were those with the most severe symptoms and they were then assigned to the medication group, they might improve less because of their greater severity, again biasing the results. This is why assigning people to groups through a flip of a coin or other random procedure is so important. The second feature is that no one—not the parents, not the individual, and not even the doctor—knows who is getting the drug and who is receiving the placebo. This kind of investigation is called a double-blind study and again serves to minimize any biases that might be introduced (probably unintentionally) into the study.

Several double-blind, randomized studies have demonstrated that the atypical neuroleptics Risperdal and Abilify are indeed more helpful than placebo for people with ASD. They are the only two medications that have undergone enough testing to have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifically for use in ASD. The results of studies of antidepressant use in ASD have been mixed, with some studies finding beneficial effects and others not, so at the time the second edition of this book was published, the FDA had not approved use of medications like Prozac specifically for ASD. This does not mean that your child’s doctor might not wish to try a non-FDA-approved drug or that such a medication might not prove helpful for your child; it just means that more testing is needed before there would be widespread recommendation of this drug’s use for individuals with ASD. Double-blind, placebo-controlled studies have found that many medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) help children with ASD who have additional problems with inattention and hyperactivity. None of these medications target the core symptoms of ASD, such as social difficulties or communication challenges, however. Typically, they address other problems, such as severe aggression, dysregulated behavior, or mood problems. This research is still in its infancy, and not enough studies have been done to be able to tell which individual characteristics predict the best success. For example, does the medication work best with a particular-age individual or with people with certain specific problems? And most medications carry some chance of side effects, so it is important to weigh risks, inconveniences, and financial costs carefully against the improvement that might be seen. Currently, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized studies suggest that medications can ease certain symptoms and thereby improve quality of life, but cannot alter the basic features of ASD. They are best used in combination with behavioral interventions.

Sensory Integration Therapy

Some children with ASD are overly sensitive to and easily overwhelmed by everyday sensations, such as certain sounds, tastes, textures, or smells, or by being touched. Their distress when encountering these sensations can be very intense. Parents sometimes describe the phenomenon as “sensory overload.” One young woman said that when she was bombarded by unwanted sounds, smells, and sights, her body would “shut down.” She described feeling completely detached, almost as if her body belonged to someone else or was a piece of furniture. One boy with ASD was so sensitive to smells that his mother called doctors in advance of his appointments to remind them not to wear perfume or scented antiperspirant. During one visit, he told his doctor pointedly that she had bad breath and threatened to leave unless she gargled with mouthwash. Many children with ASD find loud noises intolerable and will cover their ears when exposed to them. Some even have difficulty with noises that are not loud and don’t bother others, such as the hum of an air conditioner or the sound of a baby crying. Other children have the opposite problem: they seem to crave certain sensations and will go out of their way (often inappropriately) to seek these sensations. For example, one young child diagnosed with ASD loved the texture of pantyhose. He could tell if a woman was wearing them from long distances and would do everything in his power to get near enough to feel them. A girl with autism loved to press her chin into the soft inner surface of people’s elbows. Dr. Temple Grandin, the famed animal scientist with autism, craved the feeling of deep pressure; as a child, she would lie under couch cushions to create this sensation and later went on to develop her patented “squeeze machine” for the same purpose.

Sensory integration (SI) is the name of the process by which incoming sensations are interpreted, connected, and organized, something that is necessary for a child to feel safe and comfortable and able to function effectively in the environment. When a child is not able to make sense of sensory experiences, his or her behavior and learning may be profoundly affected, according to a theory advanced by Dr. Jean Ayres. She suggests that the unusual behaviors just described are due to sensory integrative dysfunction. Dr. Ayres noted that not only children with ASD, but also those with learning disabilities, cerebral palsy, and genetic syndromes, may suffer from sensory integrative dysfunction.

The goal of SI therapy is to decrease existing sensitivities, provide coping skills for remaining sensitivities, and increase tolerance for new sensations. This is done by exposing the child to a variety of sensory experiences through play and movement. The child is helped to explore many different materials and sensations. The child is given some control over the experiences in therapy but is also guided through certain activities, such as swinging, light brushing, or deep pressure, that are thought to promote better organization and interpretation of sensory input. A child who is very cautious, for example, might be guided gently through jumping activities, whereas a child who is wild and uncontained might learn to crawl through a tunnel of small chairs to learn more about spatial boundaries. Children usually enjoy the therapy, because the treatment setting is filled with fun things to climb and move on, such as ramps, platforms, mats, trapezes, and tubes. Sensory integration therapy is usually delivered by an occupational therapist. It is important to find a professional who has training in the underlying theory, as well as the specific techniques, of this treatment model.

Despite frequent anecdotal accounts from both professionals and parents that SI therapy can improve behavior and functioning, there hasn’t been much research on the effectiveness of SI therapy. Although small randomized controlled trials have shown some positive effects of this type of therapy, more research is still needed. Nevertheless, many parents and children themselves report a calming effect with SI approaches. You may want to try them out, but as with all treatments reviewed here and especially those for which there is little research support, carefully assess the benefits you see. Do others, especially those unaware of the treatment, notice any changes in your child’s behavior? Are any benefits you notice above and beyond those your child might show following a good night of sleep or participation in some other preferred or calming activity (like watching a favorite video)? You may find it helpful to keep a chart of your child’s behavior, something as simple as two columns on a piece of paper for each day, one containing information about sleep, diet, therapy, and special circumstances and the other containing information about your child’s behavior that day. In this way, you can keep track of any major changes and then examine their association with events in your child’s life, including therapy. As always, financial cost introduces some limits. It is not possible to access every type of therapy for your child, nor desirable (from a time perspective) to do so. You will need to pick and choose among interventions and so be particularly careful in scrutinizing therapies whose effectiveness has yet to be established.

There are things other than SI therapy that may be useful in building your child’s ability to organize and integrate experiences and body sensations. Movement and dance classes stress similar skills outside a therapeutic environment, as do individual sports and other fitness activities, such as martial arts training. You may want to consider some of these options as well.

Individual Psychotherapy

Traditional psychotherapy may help a limited number of individuals with ASD. Generally, individual psychotherapy involves discussion of emotions and gaining insight into behavior patterns or interpersonal issues. Since most children, adolescents, and even adults with ASD have limited self-awareness, do not naturally make social comparisons, and often show little insight into the nature and reasons for their difficulties, this form of psychotherapy is often not very helpful for them. Additionally, the realm in which the majority of problems arise for those with ASD, social situations, are best dealt with in larger group formats, rather than in individual therapy sessions. One of the chief difficulties encountered in autism is the lack of automatic generalization, from one situation to another, from one interaction to another, from one setting to another, from one person to another. It is therefore unlikely that work done in a one-to-one setting with an understanding therapist will generalize to group social situations involving peers. Thus, group therapy (often in the form of social skills training) may be a better way to address the specific issues inherent in ASD.

Under some circumstances, however, individual psychotherapy may be warranted, especially for the highest-functioning adolescents and adults, who have gained some ability to understand their own and others’ emotional states and behaviors. Individual psychotherapy may, in these limited circumstances, be helpful in dealing with the anxiety, depression, and emotional dysregulation that often accompany ASD and the pain that may accompany the growing awareness of their differences from others. Counseling should still be highly structured and rather more directive and concrete than typical psychotherapy with individuals who don’t have ASD. There should be a clear focus on specific problems, developing more effective methods to cope with them, and planning strategies to maximize the person’s potential and help him attain important life skills such as job-related social behaviors. The therapy may be highly directive and may even involve “field trips” into the community to encourage development of specific independent functioning skills (riding the bus, interviewing for a job, ordering food in a restaurant, and the like). Studies have shown that cognitive-behavioral therapy, which focuses on understanding one’s thoughts and how they influence behavior, is effective for addressing anxiety symptoms in high-functioning adolescents and adults with ASD. We talk more about cognitive-behavioral therapy in Chapter 8, and additional information is included in the Resources.

Dietary Treatments

Some professionals have advocated the use of special diets, vitamin supplements, or both to manage some symptoms associated with ASD. In recent years, a theory has been formed that some cases of autism are caused by food allergies, specifically severe allergic reactions to gluten, a protein found in flour, and casein, a protein found in milk products, that irritate or damage the brain and lead to the unusual behaviors associated with ASD. So far this hypothesis is based on clinical observations and parent reports rather than well-controlled scientific studies. It is clear, however, that many children with ASD do have difficulties with their gastrointestinal systems, and this may result in problems such as reflux, constipation, and diarrhea. It is important to talk with your pediatrician, and if need be, a gastroenterologist if your child is having these symptoms. Feeding issues, such as picky eating, are also very common. Again, your pediatrician should be able to discuss strategies for helping with these issues.

As with understanding the potential risks and benefits associated with medications, future research investigations on dietary interventions are very much needed. Some parents report improvement of their child’s behavior when certain products are removed from their diet. When children are undergoing elimination diets (that is, diets that systematically remove one type of food at a time), it is not possible to have parents and children themselves be “blind” to what group they are in. However, it is perfectly possible to randomly assign children to diet or no-diet groups and to have the scientists evaluating the children be unaware of group assignment. This needs to be done before the effectiveness of these therapies can be known. It is always recommended that such diets be conducted in collaboration with a dietician or other medical professional who is knowledgeable about potential side effects or risks and can ensure that proper nutritional needs are met.

Another form of dietary treatment for ASD is vitamin supplements. Dr. Bernard Rimland, who was one of the first professionals to propose a biological cause for autism, was a supporter of so-called megavitamin therapy, which involves administering large doses (much larger than in a typical vitamin supplement) of vitamin B6 and magnesium. These two vitamins are usually given in combination, because the mineral magnesium is necessary for proper absorption of vitamin B6. Dimethylglycine, or DMG, is another “natural substance” found in many health food stores reported to help autistic symptoms. Many parents report improvement in a wide variety of behaviors, including eye contact, social initiation, language, mood, and aggression, when their children are taking these supplements. A few studies have been conducted, some using double-blind or placebo-controlled methods, but the evidence of effectiveness is mixed. Almost all the studies had some significant limitations, such as examining very small numbers of children, not randomly assigning subjects to groups, or not using standardized methods of assessing change. We always recommend that megavitamin therapy be conducted with the collaboration of an experienced physician, because side effects of the vitamin treatments are possible, and doctors are not yet sure that the very high doses typically used are not toxic in some way.

Family Support

A final realm of treatment is the family. Relieving family distress should by no means be considered secondary or unimportant, although this topic falls at the end of this chapter. Many of the preceding treatments, if they are effective and help your child, will by extension help you and your family in general. To the extent that significant difficulties remain for members of the family, however, additional support may be necessary. Most urban areas have support or self-help groups for parents and families of people with ASD. In some areas, there are even regular meetings that are specifically for families of higher-functioning children, so that the topics of focus are specifically relevant for those with milder or higher-functioning symptoms. If such meetings are not available in your area, don’t despair, because most support groups will still make a strong effort to have some of their meetings centered on higher-functioning individuals. You just may need to call ahead and get a schedule of topics to know when it will be most relevant for you to attend. Parents often find it useful to talk with other parents, who understand better than professionals what you are going through and who may have useful remedies for situations you find your family in, even if their children are functioning at different levels. These support groups do indeed make it clear that you are not alone. Feelings of isolation at the time of diagnosis are almost universal among parents. Joining a support group will diminish those feelings considerably, as well as provide much constructive and practical assistance. Whether or not you attend regular meetings of such support groups, do contact your state autism society, an invaluable resource for relevant community programs, books, conferences, and Internet sites.