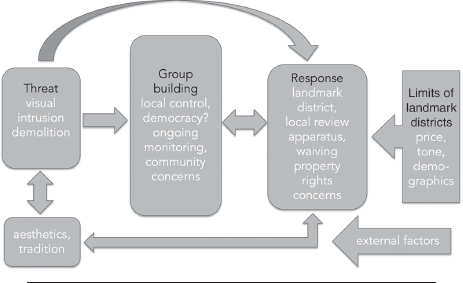

What is the relationship between historic preservation and neighborhood change? “It’s complicated” understates the case, but we have to begin there because, at some level, that is the most important contribution of this book. Historic district designation is treated by many planners and real estate economists and by many laypeople as if it had a singular and uniform effect, regardless of the history of the city or neighborhood in question. My data reveal not only that this is incorrect but also that it is a fundamental misunderstanding of historic designation. Historic designation is a dynamic and interactive process that must vary from place to place and moment to moment because it is rooted in the built environment as a social process (figure 6.1).

FIGURE 6.1 Conceptual model of landmark districting dynamics

This conclusion follows from both the diverse quantitative data I presented on Baltimore and the qualitative accounts of preservation activists in Brooklyn. In Baltimore, historic districts are demographically different from never-designated parts of the city, but how they are different is not consistent across neighborhoods, nor across time periods. They appear to change over time, and designation seems to do something. In some instances, I observed the relationship as fortification; that is, using historic designation to consecrate the relatively higher status of longtime, high-status neighborhoods. This exclusionary practice was exercised in some areas to secure racially restrictive covenants like Roland Park. In Original Northwood, though, something like fortification occurred in conjunction with the neighborhood’s transition from majority White to majority Black while improving its educated, upper-middle class profile. In other neighborhoods, such as formerly working-class White Canton, we see something like gentrification following upon historic designation. Finally, in Baltimore, we see a historic tax credit geographically distributed in ways that defy expectation but that may ultimately reflect the institutional capacity in neighborhoods.

The difficulty of doing preservation in a legacy city inflects much of what we understand about Baltimore. All of the efforts to fortify or revitalize are going on in the context of intense vacancy and abandonment reaching back decades. This shrunken and still shrinking city effect is confounded by the contemporary commitment to systematic demolition. However, Project CORE is a program hobbled by legal procedures that shows no signs yet of significantly threatening Baltimore’s historic texture. In fact, CORE’s primary legacy may prove to be the direction of rehabilitation funds into neighborhoods in ways that reverse some physical decline. Baltimore preservationists are philosophical about CORE’s impact, but the program’s very design points to the enduring power of the development paradigm, even in a city that has been shrinking for almost seventy years.

This book could not provide a portrayal of what preservation looks like from the perspective of the residents of diverse neighborhoods in Baltimore. With my research substantially complete, I managed to secure a meeting with a neighborhood activist in Easterwood, Baltimore.1 “Doc” Cheatham gave me a whole morning, walking the streets of the neighborhood, explaining its history and its present, and discussing historic designation and Project CORE, among other things. It quickly became clear that, even for someone with strong connections to the city, day-to-day issues of homelessness, abandonment, physical upkeep, and street crime overwhelmed the policy concerns and funding sources I came to inquire about. Late in this process I also secured a meeting with an officer of the Union Square Association (see chapter 4).2 The leadership of this organization is now predominantly white and professional, but they still wrestle with issues of abandonment and revitalization. These on-the-ground perspectives—experiences and motivations that drive the actions that manifest as historic district designation or applications for rehabilitation funding through Project CORE—are what we need to know more about to come closer to a complete picture of preservation in Baltimore.

In Brooklyn, I began from a place that must undermine the conventional assumption by being a kind of posterchild for gentrification in recent decades—a city of such intense development pressure that gentrification always seems to come first, always seems to be the dynamic to which community action, regulation, and policy respond. Landmark district designation becomes, in this context, one of the few options communities find to exert some control over the market-driven process of neighborhood change. It also becomes a mechanism for community building because it requires engagement and cooperation among neighbors. Even where this seems consistent, the social processes from which it emerges and its effectiveness vary from neighborhood to neighborhood, differing with phases of gentrification, architectural style and development history, demographics, and the identity and social capital of those who commit themselves to the process.

To understand central Brooklyn better still, we need more information about the results of efforts to mitigate gentrification through landmark district designation. Will it constrain property prices in Bed-Stuy or increase them? Who is moving into central Brooklyn, and is the historic built environment a motivating factor? Finer-grained data on these pushes and pulls—more first person accounts that capture experience and motivation—would help. Charting trajectories is also important; the Bedford-Union Armory is one among many unfinished stories examined here. The impact in central Brooklyn neighborhoods on real estate prices and demographic transitions during the economic downturn in 2020 following the coronavirus crisis also remains to be seen.

We can agree that the relationship between historic preservation and neighborhood change in Baltimore is about maintaining status and facilitating revitalization, whereas in Brooklyn it is a matter of mitigating gentrification and claiming some degree of community control. Baltimore and central Brooklyn are not precisely the ends of a spectrum of urban trajectories, but they do represent radically different urban contexts, kinds of cities, that reveal broader differences in how preservation efforts can manifest and their policy potential. Placing them on some kind of a spectrum enables contrast, and we need to rejoice in this contrast rather than declaring it anomalous. We also need to recognize the idiosyncrasies and interdependencies of these accounts. The relationships between preservation and neighborhood change may be as I describe, but mine is not a complete explanation, nor does it identify an independent mechanism.

The depth of the contrast between Baltimore and Brooklyn could be about the insufficiencies of my method, the incompleteness of my account. But it is more likely that my characterization of top-down processes in one city and bottom-up processes in the other is roughly accurate, despite my preference for telling a more encouraging story about legacy city Baltimore. The governance of a legacy city in a long era of federal urban policy withdrawal is often about trying anything and everything, and in Baltimore’s defense, I have not observed any top-down policy that seemed to further disempower its residents.

In the broadest sense, my research points to the radical specificity and contingency of urban dynamics in the United States. The careful examination of historic district designation processes in Baltimore and Brooklyn reinforces this by revealing that local preservation policies may share principles but that designation processes vary according to the history and composition of neighborhoods and cities. Neighborhoods are particular, and the trajectories along which they change (or remain the same) are substantially specific to them. This should not discourage us as urban scholars but reinvigorate our attention to local dynamics, particularly in conversation with any national scale or interurban comparative work. It is another call for the necessity of bridging the micro and macro by digging deeper into the micro.

If we can move beyond the conventional assumption that historic preservation causes gentrification, we can consider all of the diverse things it does do—the purposes it does serve in contemporary U.S. cities beyond those for which it was intended. Preservation may serve indirectly as a mechanism for revitalization in the presence of historic tax credits. It is difficult to characterize their distribution in Baltimore, and I found no connection between tax credit–linked investment and neighborhood change. However, indications are that these credits facilitate investment in (some) historic neighborhoods. I have de-emphasized the importance of the federal rehabilitation tax credit because it rarely applies to owner-occupied residences, but I will remind you that Ryberg-Webster and Kinahan identify it as the second largest source of federal subsidy for most cities, behind only the Community Development Block Grant.3 Like the CDBG, the federal rehabilitation tax credit reflects the withdrawal of the federal government from an affirmative urban policy and reveals what Hackworth calls “the logic of local autonomy.”4 There is good evidence to connect local preservation policy, historic tax credits, and investment, but the outcome of this investment is less clear.

More important for my purposes and more novel is the observation that historic district designation serves as the basis for important community organizing efforts. Although we cannot see that in my Baltimore data, it is conspicuous in Prospect Heights, Crown Heights North, and Bed-Stuy, each in different ways. Designation as community action is generally important for building neighborhood social capital, as in PHNDC’s efforts to shape the Atlantic Yards project, but different and more important in neighborhoods that have been historically marginalized and still face greater challenges associated with that marginalization. CHNA’s role is different from PHNDC’s because of the demographics and history of the neighborhood and because of the founders of the organization. Brown-Puryear and Young refer to efforts to respond collectively to predatory lending that targeted elders in Crown Heights North,5 whereas Ethel Tyus talked to me about working with commercial landowners to stabilize neighborhood services for longtime residents. They are working to preserve the benefits of neighborhood revitalization for people who have lived through decades of disinvestment.

The Brooklyn accounts show the limits to the kind of control that organized communities can exercise over their neighborhood through designation, even if they have built intensive connections and pursued a kind of preservation of community. Foremost among these limits is the inability to concretely intervene in the real estate market (which, of course, confirms our sense that the conventional account is missing something). They can instruct their neighbors in the kind of allowable and appropriate alterations to the architectural styles associated with the neighborhood, but they cannot keep their neighbors from selling to wealthy in-movers and moving away. Nor would they want to necessarily, although those who remain bemoan the changes that come with the changing demographics of the neighborhood. Landmark district designation is an imperfect mechanism for communities to use to intervene in the gentrification processes they see going on around them in part because it was not intended for that purpose.

The difficulties of organizing are also essential to acknowledge, prior even to recognizing the limits of designation. In Crown Heights South, the desire to intervene in the development process as their neighbors to the north do is frustrated, as is the ability to shape the process of redevelopment of the Bedford-Union Armory. The difficulty of organizing often comes down to the presence of individuals like Evelyn Tully Costa who has the personal and interpersonal wherewithal to effect community action. When those individuals confront reversals of their own, however, the cost to the organizing process can be profound.

A cautionary note, though, lest the reader perceive me as championing the community organizing potential of the designation process uncritically: Bankoff, of the Historic Districts Council, identified the risk of NIMBY implicit in some designation efforts. Chadotsang, too, in his time at LPC, saw designation undertaken to exclude. As David Harvey and Thomas Sugrue have both identified in writing about very different topics, community organization can often accomplish regressive ends.6 This again returns us to the necessity of attention to specific examples as opposed to presuming a positive and uniform effect emerging from the community organizing aspect of designation efforts.

Many questions about the relationship between historic preservation and neighborhood change remain unanswered. The most obvious are about what this relationship looks like in other cities and other neighborhoods. Having identified complication, I want to call for further efforts to complicate, and work like this is beginning to emerge.7 We need both broader and deeper understandings of the variation in preservation policy, the purposes to which preservation regulation is put, the diverse outcomes of designation efforts, popular conceptions of preservation, and the motivations for pursuing it.

Some questions pertaining to the cities that I have explored here also deserve additional attention. What will Project CORE ultimately produce? Will more Baltimore neighborhoods capitalize on the kinds of change that some have accomplished as others continue to shrink? Are there other neighborhoods in Brooklyn (and the rest of New York) that embody interesting stories about preservation as an exercise in community organizing and mitigation?

Throughout this research, I struggled with the intellectual problem of my “most different” comparison. My next step will be to find the middle of that spectrum, and I propose a city roughly halfway between New York and Baltimore in many ways. Philadelphia has an extensive historic built environment, similar to both Baltimore and Brooklyn in important respects. Philadelphia experienced radical shrinkage similar to that of Baltimore, losing more than a quarter of its population between 1950 and 2005. This has left large swaths of the city, mostly dense blocks of brick row houses near industrial sites in North Philadelphia, partly empty and plagued by abandonment similar to parts of Baltimore. But the population trend in Philadelphia has turned around, and the city has been growing for more than a decade and becoming more diverse. This is not the overheated real estate market of New York City, but the city council has understood that a tax abatement intended to encourage redevelopment downtown has served its purpose and is now being exploited by developers. Philadelphia is growing.

“I’m a sociologist, not a policy maker,” I say to my students, “that’s what I’m teaching you to become!” That said, I see lessons in this research for urbanists generally. We should embrace the potential of historic preservation to revitalize and mitigate and engage it directly. Historic preservation is one of the primary urban policy tools available to us that leaves substantial control over process in the hands of the neighborhood residents most immediately affected. That should lead us to encourage communities to take advantage of it, particularly those historically underserved by preservation efforts.

Preservation as a policy tool is most relevant in older U.S. cities. That is less of a constraint than the concern with how to align its impact with the interests of renters in neighborhoods dominated by rental housing. Preservation has often disproportionately favored the interests of the wealthy, but we should not concede yet that is an inevitable characteristic. There is an opportunity to use preservation rules to help regulate the quality of more affordable, market rate housing and to build community among renters and homeowners on the basis of the built environment they share in common.

I hope readers will take away many things from this research. Foremost among them is the clear sense that part of the complication of living in contemporary U.S. cities is that we inhabit an enduring built environment. Whether we intentionally preserve it or not, most of us live among and in buildings built long ago. Historic preservation efforts focus our attention on that enduring built environment and articulate one version of the role of that stuff in our lives. More important for me than the preservationist perspective is the way that the process, the struggle, reveals these ongoing relationships.