Lewis N. Mander

Lew Mander grew up in New Zealand and completed his B.Sc. and M.Sc. (Hons) degrees at the University of Auckland (1957–1961), from where he moved to Australia perform his Ph.D. on steroid synthesis and alkaloid structure determination at the University of Sydney under the supervision of C. W. Shoppee, E. Ritchie, and W. C. Taylor. After two years of postdoctoral studies with R. E. Ireland on the total synthesis of diterpenes, initially at the University of Michigan and then at the California Institute of Technology, he returned to Australia in 1966 as a lecturer in the Department of Organic Chemistry at the University of Adelaide. In 1975 he was appointed to a senior fellowship in the Research School of Chemistry (RSC) at the Australian National University, Canberra, and in 1980, to his current position as Professor of Chemistry. During the periods 1981–1 986 and 1992–1995, he served as Dean of the RSC.

He has been a Nuffield Fellow at Cambridge University (1972) (with A. R. Battersby), a Fulbright Senior Scholar at the California Institute of Technology (1977) and at Harvard University (1986) (with D. A. Evans on both occasions), and an Eminent Scientist of RIKEN (1995–1996, Saitama, Japan).

In 1983 he was elected Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science and in 1990 was elected Fellow of the Royal Society. Furthermore, he is an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand and a Distinguished Alumnus Professor of the University of Auckland. Among his numerous awards are the H. G. Smith and Birch Medals of the Royal Australian Chemical Institute, the David Craig Medal of the Australian Academy of Science, and the Flintoff Medal and CIBA Award in synthetic organic chemistry of the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Scientific Sketch

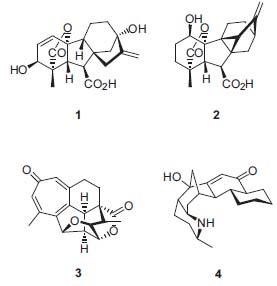

Mander’s research interests are concerned primarily with methodology and strategies for the total synthesis of complex natural products that have interesting biological properties, such as gibberellic acid (1), the antheridiogen (2), harringtonolide (3), and the galbulimima alkaloid (4). Arising out of these endeavors has been the development of a range of useful methodologies, including Birch reductions, diazoke-tone-based chemistry, refinements to the Wittig reaction, unusual aldol and Michael reactions, and the use of cyanoformates for the kinetically controlled C-acylation of enolate anions.

Another major interest embraces the gibberellin family of plant bioregulators (Chem. Rev. 1992, 92, 573). He is concerned with the isolation (Phytochemistry 2002, 59, 679; 2000, 55, 887; 1996, 43, 23), synthesis (Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 723), structure determination, and biosynthesis of natural plant growth regulators with special reference to the gibberellins (GAs). GAs affect every aspect of plant growth and development, but their most typical (and spectacular) property is the induction of stem growth. The phenomenon of bolting in rosette plants (e.g., spinach and radish) is caused naturally by endogenous GAs (J. Jpn. Hortic. Sci. 1999, 68, 527), while the hybrid vigor obtained in maize has been shown to be due to the production of higher than normal levels of GAs. Flowering is stimulated by GAs (Physiol. Plant. 2001, 112, 429; 2000, 109, 97), which can also delay senescence, promote the germination of seeds, and eliminate the need for vernalization (winter chilling) in the growth of bulbs and tubers. GAs are associated with the breaking of winter dormancy and stimulate the formation of hydro-lases and amylases.

One of his studies on the biology of GAs, pursued in collaboration with groups in CSIRO Plant Industry and the University of Calgary, has led to the discovery of semi-synthetic derivatives that selectively promote flowering but little or no growth (Phytochemistry 1998, 49, 1509); somewhat surprisingly, some analogues actually inhibit growth. There is a major demand for growth retardants in agriculture, and because these modified GAs can be expected to be environmentally benign, they have considerable commercial potential (Japanese Journal of Crop Science 1999, 68, 362; Acta Horticulturae 1995, 394, 199). A new project is directed towards the identification of GA molecular receptors.

Chicken Dijonnais

Starting materials (serves 4):

500 g skinned chicken thighs

20 mL olive oil

20 mL brandy (optional)

100 mL white wine

2 cloves garlic

10 mL smooth Dijon mustard

freshly ground pepper

200 mL chicken stock

few sprigs of fresh thyme or tarragon

Pat chicken pieces dry with kitchen paper and brown in frypan with the oil.

Flambé with brandy.

Add wine, peeled and crushed garlic, mustard, pepper, stock, and thyme (tarragon).

Mix well, cover, and simmer over very low heat for 40 minutes.

Remove thyme, separate liquid, and keep chicken pieces warm.

Reduce liquid to desired consistency and pour over chicken.

Serve with a Chardonnay, Australian, of course.

«For me, cooking is too much like a busman’s holiday. Fortunately, I am married to a superb cook (also an organic chemist). The above recipe is selected from her repertoire and is one of my favorites.»

Lew Mander