1. George H. W. Bush, thirteen, in 1937 at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. As president, returning in 1989, he said, “I loved this school, this place.” GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

More often than not, presidents hire personnel whose qualities offset, not duplicate, their own vulnerabilities. For example, just as Lyndon Johnson, roughhewn and coarse, lured such soft-spoken loyalists as George Christian and Horace Busby; just as Richard Nixon, constitutionally unable to brook personal confrontation, required H. R. Haldeman as his Official Son of a Bitch; just as Gerald Ford, open and amiable, needed Robert Hartmann to ward off outsiders; just as Ronald Reagan, a delegator unschooled in Washington, needed street-smart Chief of Staff James A. Baker—so, I wrote in early 1989, would George Bush, gentle, civil, a conciliator by nature, require White House appointees who were tough and tough-minded, facile and assertive, fiercely loyal to the new president’s person and policies, and even brutal in their execution. In short, the forty-first president would need people who mirrored Nixon’s praise, circa 1972, of George Herbert Walker Bush: “He’ll do anything for the cause.”

There are exceptions to every rule, but Democrats themselves best expressed what Bush faced, becoming president. “He may get a fifteen-minute honeymoon after he takes his hand off the Bible,” said Representative Richard Durbin of Illinois. California representative Robert Matsui was less charitable, bragging, “This guy’s not going to have any honeymoon at all.” To confront academics, foundations, and Hill Democrats; fight the special interests vs. general; and go above a hostile media to reach and move America, Bush did not need nice guys. He was decent enough for an entire staff.

The 1988 campaign showed brilliantly that this patient, generous, and kindhearted man could paint political pitchfork-populist art when linked, arm in arm, with aides who loved their country, hated what extremists had done to it, and did not dislike rolling up their sleeves, extending elbows, and using what they deemed necessary means to reach their end. To help the Bush presidency enrich 1990s America so that America could enrich the world, he and they, I believed, must be no less combative now.

In early 1989 I was hired as a speechwriter to Bush 41. The FBI did its usual indefatigable job probing every crevice of a nominee’s life, knowing, for example, the name of my childhood dog, who was sadly unable to testify, having died when she was ten. My time at Gannett, at the Saturday Evening Post, and in the Reagan cabinet helped. As we have seen, a fall 1988 ad hoc media campaign group introduced me to people who joined the administration. Raymond Price again wrote on my behalf to Bush’s new communications director, David Demarest, a moderate New Jersey Republican and public affairs official in Reagan’s Labor Department.

Demarest knew, as historian Arthur Schlesinger’s son Robert wrote in White House Ghosts: Presidents and Their Speechwriters, a history of modern presidential speechwriting since its birth in the early 1920s, that “Bush and his top advisors did not attach the same value to speechmaking that Reagan had.” Demarest thought that Reagan’s writers had too high a profile, were too self-absorbed, and resembled radio’s 1940s serial The Bickersons. Instead, the communications director wanted team writers who played nice, were loyal, and checked ego at the door.

With luck, a varied staff might also serve Bush and the two occasionally harmonic but often warring wings of the GOP. The Main Street wing supplied most of the party’s votes: a Silent still-Majority trying to save, buy a home, and educate their children. It touted sane tax and spend, limited government, the Bible as moral compass, and America as freedom’s beacon. The Wall Street wing supplied most of the party’s money. It touted globalism, increasing secularism, free if not necessarily fair trade, outsourcing, and a conciliatory or me-too political ideology, depending on your definition. The wings seldom overlapped.

Eisenhower fused them in 1952 and 1956; having dispatched Hitler, he left political quibbling to mortals. Nixon embodied Main Street and groveled for Wall Street’s largesse. In 1976 and at first in 1980, Wall Street thought Reagan a troglodyte. A decade later, prosperity all around, he seemed almost as good as Milton Friedman. In 1988 Wall Street financiers forgave Poppy’s impression of Grant Wood’s American Gothic; Prescott Bush’s son didn’t—couldn’t—mean it. White House writers might reduce the gulf.

In particular, Demarest, with a fine sense of humor, wanted Bush to get audiences to laugh. David had a late-night comedic attitude. Alas, as this book notes (see the “Author’s Note” re: Aretha Franklin’s song “R-E-S-P-E-C-T”), Bush was not a late-night kind of guy. We compensated by using humor writer Doug Gamble, key to Bush’s 1988 acceptance speech, and adopting the president’s cultural milieu, which considered “hipness” another word for as transient as the wind. My humor ran toward black comedy, forged as a child by the 1960 election and the Boston Red Sox. A ballad goes, “Being Irish means laughing at life knowing that in the end life will break your heart.” What counted was Bush’s humor. We would learn by trial and error.

In the book President Kennedy, Richard Reeves writes that JFK “came to power at the end of an old era or the beginning of a new, which was important because his words and actions were recorded in new ways. The pulse of communications speeded up in his time.” So did Bush 41. At the beginning of his term, we had electric typewriters, fax machines, and primitive computers, which the technology challenged—e.g., me—did not know how to use. We had to learn quickly on the job. E-mail did not exist; neither did a social media that later tied “iPod” and “hashtag” and “iPad” and “tweet.” As these new technologies grew, they helped the Democrats win four of six presidential elections from 1992 to 2012. In 1989 I was absorbed by words like “save,” “search,” and “shift”—and above all, the Indian saw “you can only know someone by putting your feet in their moccasins.”

Our great adventure began January 20, 1989, George Bush giving the inaugural address that from his 1960s and ’70s wilderness, even as recently as the 1988 Democratic Convention, must have seemed as distant as the green light to Jay Gatsby at the end of Tom and Daisy Buchanan’s dock. Writer Peggy Noonan cast the site as “democracy’s front porch.” Bush’s “first act as president” was a prayer. He then began a theme—“a new breeze is blowing”—freedom. “We know what works,” he said. “Freedom works.” The new president paraphrased from Saint Augustine: “In crucial things, unity; in important things, diversity; in all things, generosity.”

Government could help, but only people could inspire. “[Together we could] make kinder the face of the Nation and gentler the face of the world.” To 41, the bully pulpit meant example. Example meant bipartisanship. Goodwill begat goodwill. At one point Bush turned from the lectern and extended his hand to Speaker of the House Jim Wright and Senate majority leader George Mitchell. “For this is the thing,” Bush said. “This is the age of the offered hand.” Too late he sensed that Democrats wanted his head, not hand. For the moment, drugs inflamed him most. “Take my word for it: This scourge will stop.” The speech ended with a fifth use of “breeze.” Noonan then left speechwriting to pen a Wall Street Journal column and write books, including What I Saw at the Revolution: A Political Life in the Reagan Era, the Gipper’s presidency in vivid prose.

Directly I officially began as speechwriter to the president. My office was room 120 on the first floor of the Eisenhower EOB, the former State, War, and Navy Building across West Executive Avenue from the West Wing door. It was large with a high ceiling and looked out on traffic on Seventeenth Street. The huge pillared and porticoed building looked like a skeleton from Victorian London. I liked it because it was historic and idiosyncratic and you could be in the Oval Office in less than five minutes. Since 1969 writers had been housed in the Old EOB—their corridor known as “Writers’ Row” or “Kings’ Row,” Theodore White wrote of the Nixon presidency, since Nixon had a first-floor EOB office hideaway. Under Bush, writers occupied offices to my right and left.

One was Dan McGroarty, a foreign policy specialist, having crafted speeches for Secretaries of Defense Caspar Weinberger and Frank Carlucci and worked at Voice of America. Another, Mark Davis, had written speeches for RNC head Frank Fahrenkopf. Mark Lange joined us from the Transportation Department, having worked for Secretaries Ann McLaughlin and Elizabeth Dole. Mary Kate Grant (later Cary) wrote magazine articles, then speeches, for Bush. Ed McNally had been a federal prosecutor in New York. Beth Hinchliffe was a lyric Boston magazine writer. I and several others served all four years of the Bush administration. Until 1992, when, paraphrasing Yeats, its center no longer held, most served at least two.

Bush’s speech team resembled each president’s since the 1960s, numbering five or six writers at a time, each assigned a research aide to cull local story, fact-check, and mediate with local people. Some writers served as alter ego, policy aide, or personal assistant. Some were a speechwriter before entering the White House, with a field of concentration: foreign policy, domestic policy, values and philosophy. Writing could be by committee and sound it. Most presidents agree: one writer, one speech works best. Bush worked with a single writer on a speech, assigned by Demarest from the West Wing, a floor above the president, and speech editor Chriss Winston, housed on Writers’ Row.

For a major speech—State of the Union, UN address, network missive—you might have twenty days to visit aides, policy experts, and the president by phone, later e-mail, or in person and then write a draft. You tried not to abuse your stay; the president’s plate was always full. Ultimately, for most speeches—fund-raiser here, Rose Garden greeting there—you knew your principal so well you could write without consulting him. My Gannett past helped me write on deadline. Especially in an election year, I might arrive at 6:30 a.m., get a phone call at 7, and hear, “The president needs a speech. No hurry. Get us a draft by 11”—11 a.m. I then remembered Reagan terming himself the king of the so-called B-movies: “A B-movie is one they didn’t necessarily want good. They wanted them Tuesday.”

A former aide to liberal Iowa representative Jim Leach, Winston primarily edited more than wrote. Receiving a writer’s draft, she performed varying degrees of surgery, then sent the product to pertinent policy and political aides—the “staffing” process—each of whom played Broadway critic. Some suggested helpful prose and programmatic thoughts. Others strove to be a pain in the patootie—and succeeded. All returned changes to Chriss’s office, where we tried to reconcile the oft irreconcilable—the “reconciliation” process. After that the speech reached “POTUS” (for president of the United States), who may or may not have been previously involved.

If Bush liked the speech, happy days were here again. It was printed in bold twenty-four-point type so that he could deliver it without glasses—hopefully, but not always, practiced. By contrast, since only POTUS’s vote counted, if he disliked the final draft, it entered, as Reagan said of Communism, your ash heap of history. Scrap your weekend, turn on the computer, and as a great writer, Red Smith, said, “open your veins, and watch the blood come out.” Mercifully, I had to start from scratch only once or twice—so the Red Cross was never called.

On January 21, 1989, Bush—surprisingly taller (six foot two) than Reagan, less angular and more handsome than on television, lithe, still an athlete—entered the Roosevelt Room to tell writers what he liked and disliked about speechwriting and giving. The first rule was to avoid the word I. Such modesty was thought to be unprecedented for a politician—the result of mother Dorothy’s lifelong circumspection. “Fine, George, but what about the team?” she would say as he detailed a boyhood home run. Like River City, ditching I caused capital T, which stood for trouble. Try writing a third-person speech.

Bush’s second rule was to be direct, voiding emotion. “If you give me a ten, I’m going to send it back and say, ‘Give me an eight,’” he said. “And you’ll be lucky if I deliver a six.” A voter once compared two candidates: “Think of them as a violin. When one talks, you hear every squeak of the box. When the other talks, you hear his soul.” To Bush, the squeak was safer.

Bush’s third rule stemmed from grasping what he was and wasn’t. “I am not Ronald Reagan,” he told us. “I couldn’t be if I wanted to.” The spoken word had been Reagan’s presidency. By design it was one aspect—like policy or personnel—of Bush’s. James Agee wrote, “Let us now praise famous men.” Bush’s famous man said, “You can observe a lot by watching.” As observed, Reagan liked to quote Jefferson. No matter an audience’s age, race, sex, or education, Bush quoted Yogi Berra. With certain people—Sinatra, Streisand—only the surname counts. Others flaunt first name or initial: Ellen, W. No name is like the Yog’s.

Born to Italian immigrants, Berra grew up on St. Louis’s “Dago Hill.” Once the squat, jug-eared teen and a friend saw a theater travelogue about India. The film included a yogi, likened to Berra by his pal. Like gold, the nickname stuck. Yogi learned a salute to the flag, catch in the throat, tear in the eye Americanism. Best friend and future broadcaster Joe Garagiola lived “a pickoff away.” One day Berra took ill. “You look terrible,” said Garagiola. “Why don’t you go home?” Yogi shrugged: “If a guy can’t get sick on a cold, miserable day like this, he ain’t healthy.”

Such logic endeared him to America, where by the early twenty-first century Yogi passed Shakespeare as the figure most quoted by U.S. public speakers. Yet Baseball Hall of Fame Class of ’72 was more than “Yogi thinking funny,” said Garagiola, “and speaking what he thinks.” Like Bush, Berra braved World War II as a teenager. Back home he became what the ex-Yale captain termed “baseball’s greatest catcher”—three-time Most Valuable Player, 358 homers, and the position’s most runs batted in—showing that “baseball is 90 percent mental,” said Berra. “The other half is physical.”

“If you can’t imitate him, don’t copy him,” Yogi said, as Bush said of Reagan. No one could copy baseball’s most lethal bad-ball hitter. Number 8 also rolled seven behind the plate. Once Berra fielded a bunt and tagged the hitter and runner coming toward the plate, saying, “I just tagged everybody, including the ump.” Yogi leads in all-time World Series games (75), hits (71), played (14), and won (10). If Berra were a movie, it would be The Quiet Man meets Mr. Lucky.

Yogi and wife Carmen were wed from 1949 till her death in 2014. The bowling alley Berra and ex-Yankee Phil Rizzuto opened rolled a financial 300; Yogi’s Yoo-hoo drink became a hit; Aflac ads remain a classic—Berra, in barber chair; barber and duck, agape. In 2008 Yogi helped close the original Yankee Stadium. About this time, he said, “Always go to other people’s funerals. Otherwise they won’t come to yours.” Mercifully, baseball’s extraordinary Ordinary Man’s funeral seemed more than a short pop fly away.

Ultimately, I found that Bush knew more Berraisms than I did. “Nobody goes to that restaurant anymore. It’s too crowded.” A woman cooed, “Yogi, you look cool in that suit.” Berra smiled: “Thanks. You don’t look so hot yourself.” In 2009 Bush intern–turned–counselor Julie Harry Heiden invited me to keynote the Fairfax County, Virginia, Bar Association. Speech like “It’s déjà vu all over again” dotted my address. Part-time college waiters left the kitchen to hear Berraisms they’d never heard. This is not uncommon. When it came to quotation, George Bush was far ahead of the curve.

For his first few months, finding my way around, I wrote about the environment, law enforcement, the growing savings and loan crisis, and the role of government. At American University Bush quoted Bernard Baruch to define his philosophy of pragmatism: “Government is not a substitute for people, but simply the instrument through which they act.” At Ford Aerospace in Palo Alto, Bush said, “The genius of America has forged the greatness of America.” In New York he defined justice at the United Negro College Fund dinner, recalling how at Yale Bush helped its drive while trying to captain the varsity and steady his grades. “I observed what Churchill said, ‘Personally, I am always ready to learn, though I do not always enjoy being taught.’”

For a long time, Bush could boast of prosperity without inflation and prosperity without war. One-line phrases reflected his, as it had been Reagan’s, forte. “A strong economy is the surest guarantee of lasting social justice.” Abroad, from his first full month Bush renewed acquaintances and alliances from his globe-hopping time as veep in Canada, China, and South Korea. In Japan for Emperor Hirohito’s state funeral, he met French president François Mitterrand, recalling Lafayette’s “What impresses me is that in America all of the citizens are brethren.” Bush swore in, among others, James Baker at State, Dick Cheney at Defense, William Bennett at Education, Elizabeth Dole at Transportation, and John Sununu as chief of staff. When possible, writers watched and listened, tried to measure Bush’s voice and cadence, and adjusted ourselves to him, and he perhaps to us.

That spring, presenting Volunteer Awards, Bush spurned “what I can do for myself” for “what I can do by myself for others.” The greatest gift, he said during Captive Nations Week, was freedom: “The totalitarian era is passing, its old ideas blown away like leaves from an ancient, lifeless tree.” In 1942 Gen. James A. Doolittle led a squadron of planes off a U.S. aircraft carrier to bomb Japan—“Thirty Seconds over Tokyo”—pivoting World War II morale. In June 1989 Bush gave the Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian award, to Doolittle for having “shown that ours would not be the land of the free if it were not also the home of the brave.” By contrast, that month he addressed members of the Memorial Advisory Board about the Korean War Memorial—a postcard summer day. As noted, Ted Williams was a close friend. Bush knew his nickname—Teddy Ballgame—yet called him Ballgame Teddy, having not read the speech to know it—or know how the words would sound.

“He [Bush] just didn’t buy into that,” Demarest told Robert Schlesinger of a belief that success demanded eloquence. “It wasn’t in his DNA.” He rarely practiced reading speeches out loud, the exception a major address: a UN, prime-time, or Oval Office message. Noonan sent me a note, saying, “Bush, as you know, is skeptical of sweeping rhetoric. He likes it low-key. But that means you guys can’t show what you’ve got and soar! And then you get knocked for not soaring!” Some higher-ups added insult by “de-Reaganizing” our staff—the Gipper’s, they felt, too big for their britches—revoking White House mess privileges and curbing West Wing access. We largely ignored or outmaneuvered such barbs. What hurt was the lack of more dialogue, even disagreement, among writers and between us and higher members of the White House staff through memoranda designed to make all of us, as Lincoln said, “think anew.”

Such memoranda were invaluable to the 1980 Connally campaign, fall 1988 Bush Fifteenth Street ad hoc effort, and virtually every presidential speech outreach since FDR’s. They spur contention, yes. They can be untidy. They can also adjust the political game plan when the original plan dissolves, as Bush’s did in late 1991 and early 1992. I traded memos with Sununu, policy expert Jim Pinkerton, and then– Dan Quayle chief of staff Bill Kristol, now the Weekly Standard publisher. Other writers doubtless conversed with policy sources of their own. Missing was the spirit of invitation whereby we were urged to contribute cerebrally and emotionally to the larger picture of reelecting George Bush.

Eddie Gomez, who played bass with pianist Billy Evans, termed the jazz musician’s aim “to make music that balanced passion and intellect.” That should be a speechwriter’s aim, exactly. Any administration needs to recall who elected it; address its constituents’ priorities; and galvanize its base. Bush had been taught to hide his good Episcopalian soul. Without doing damage or an extreme makeover, our office tried to show it.

Totalitarianism was passing, Bush had predicted in early 1989. The Polish government agreed to hold free elections, Mikhail Gorbachev refusing to intervene. As Reagan prophesied, the rest of Europe fell. Hungary began dismantling the fences along its Austrian border. The Soviet Union held its first multicandidate election. In late May Mark Davis wrote a fine speech on Germany that detailed America’s emerging Eastern European strategy: the Cold War would end “only when Europe is whole, and free.” Freedom was in the air, Bush said, again prescient. In early July he revisited Europe, a rousing speech by Ed McNally scoring at the Polish shipyard in Gdansk.

Bush then flew to Budapest, where several hundreds of thousands gathered in Kossuth Square, his text reading “liberty can light the globe.” It recalled Lajos Kossuth, a patriot who arrived in America in 1852 to salute “the principle of self-government” after Hungary’s Revolution of 1848 had temporarily been lost. In New York Harbor, an armada of ships sounded horns to hail his arrival. “Perhaps no visitor since Lafayette had been greeted so emotionally.”

My assistant, Stephanie Blessey, found a fact with which Bush’s text ended. More than five centuries earlier, Hungary’s János Hunyadi had stopped a would-be Turkish invasion. In his honor the pope ordered each Catholic church to ring a bell at the time of day the battle had ended. Since then Catholic and other Christian church bells all over the world have rung precisely at midday. “Together,” Bush was to conclude, “let us raise what Kossuth called ‘the morning star of liberty.’”

His audience might have, except that Budapest had been pelted all day by torrential rain—a fact of which we were unaware in Washington in that pre–cell phone, iPod, and even largely cable-TV age. We were in the speech office, listening by squawk box—an intercom link with the speech site—no picture, explanation, or above all, context. Hungarian president Bruno Straub gave a stolid fifteen-minute introduction. Bush then began to speak, saying, “I’m going to take this speech and I’m going to tear it up. You’ve been out here long enough.”

Hungarians roared as Bush ripped the speech cards—my cards—and held them above his head. Blessey’s head hit the table. I tried to mask surprise, wondering what we’d done to deserve such a public flogging. Next day, word filtered back about Bush’s ad-libbing, then waving the crowd home. Translated, the text would have lasted forty minutes in the rain; Bush was being kind. Later he sent me a Reuters photo that graced papers around the world: 41, in trench coat, smiling gleefully, holding half of each card in one hand and half in the other. “It’s raining in Budapest,” he wrote. “I’ll wing it.” Bush winged little about foreign policy, as his administration showed.

In his inaugural Bush had referenced the need to move beyond Vietnam: “That war cleaves us still.” In November 1989 he dedicated the Texas Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Dallas. In White House Ghosts, Schlesinger wrote that I “specialized in speeches that appealed to the conservative base of the GOP—rallying-type addresses that touched on values issues and conservative philosophy.” Actually, the speeches that meant most to me were those that touched Bush viscerally, because they showed an extraordinary human being. In Dallas Bush related a mother who had four children, each of whom had a dream. Two of her sons were killed in Vietnam. The daughter’s dream had been to shake an American president’s hand. Said Bush, voice breaking, “It is I who am honored to shake your hands.”

That week Communist guards allowed passage through the Berlin Wall, ending twenty-eight years of a divided city. At Bush’s 1942 prep school graduation, Secretary of War Henry Stimson had said the U.S. soldier should be “self-confident without boasting.” The president now struck that balance. Press secretary Marlin Fitzwater wanted him to make a statement to the press. “Listen, Marlin,” Bush said. “I’m not going to dance on the Berlin Wall. The last thing I want to do is brag about winning the Cold War, or bringing the wall down. It won’t help us in Eastern Europe to be bragging about this.” That day a reporter said, “Why don’t you show the emotion we feel?” Unsaid: You don’t insult potential colleagues. “I wanted the Soviets’ help,” Bush said. He never said “The Cold War is over” until Germany reunited on October 3, 1990.

In late November 1989 Bush added authenticity to humility as he traveled to the historic Mediterranean island of Malta for his first meeting as president with Gorbachev. My office, like many in the EOB, had a sofa, which I used awaiting the response of “staffing” to late-night speech drafts. After reconciling their changes, I sent Bush his draft. He then began his handiwork, writing “self-typed” notes. The president’s sole speech of the summit was to the five thousand sailors on USS Forrestal. My draft included allusions to current entertainment. “Please re-do,” typed Bush, who unlike most pols refused to say anything he felt even slightly phony. “I don’t understand some of the humor. I’d [also] prefer to leave out most of the references to my own Naval experience.” Bush’s view was hard to miss. In the margin next to that paragraph, he wrote, “Too [much] ego.”

My first draft to reach Bush ended with a prayer Franklin Roosevelt spoke, on D-day, over a nationwide radio network. Instead, Bush asked for his presidential frame of reference—and his December 1 remarks concluded so:

Let me close with a moment you’re too young to remember—but which wrote a glorious page in American history. It occurred on D-day as Dwight Eisenhower addressed the sailors, soldiers, and airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force.

“You are about to embark,” he told them, “upon a great crusade. . . . The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you.” Then Ike spoke this moving prayer: “Let us all beseech the blessing of Almighty God, upon this great and noble undertaking.”

Like the men of D-day, you, too, are the hope of “liberty-loving people everywhere.” As the Navy has been in wartime—and in peacetime—keeping our hearts alight—and our faith unyielding. Sacrificing time away from your homes so that other Americans can sleep safely in theirs.

Voice wavering, the president observed, “Thank you for writing still-new pages in the history of America and her Navy. God bless you and our ‘great and noble undertaking.’ And God bless the United States of America.”

Listening, I thought of my parents, who rejoiced when Ike was elected, and my grandparents, who cried when he died, and my hometown, which supported him, and Ike’s hometown, which molded him—and of how only FDR, I believe, eclipses him as a pillar of Henry Luce’s American Century. Later Bush marveled, “It’s amazing what occurred in a blink of history’s eye.” He meant 1989–91 but could have meant World War I or II or Korea or Vietnam—all wars Ike either served in or observed.

On December 19, three weeks later, Bush asked his speechwriters to the residence for drinks, where his breeding masked a pokerfaced heart. His grandkids were all over him. The family’s English springer spaniel, Millie, licked my hand. Bush showed us the Lincoln Bedroom, noting that there Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation. He observed a painting of Lincoln and his generals—The Peacemakers—on the wall, saying that he constantly drew strength from Lincoln’s example. I thought again that at heart Bush was a deeply religious man. We spoke for an hour, Bush several times drawn to the doorway to speak with aides—even so, a president at seeming ease with the world. At 7 p.m. we rose, Bush leaving to host a media Christmas party. Seated to his left, I was the only one close enough to hear him say, “I feel a thousand years old”—understandable, I thought, for any Republican president having to mingle with the press.

At about 2 a.m., unable to sleep, I turned on the television to see Marlin Fitzwater reveal America’s invasion of Panama to snare drug kingpin Manuel Noriega. Earlier that week Noriega had declared war on America, Panamanian soldiers killing unarmed U.S. marines. Bush ordered the invasion—Operation Just Cause—to restore democracy and jail Noriega on drug-related charges. Meeting, we had no idea that Bush had already approved the gravest decision of his presidency. As Robert Schlesinger wrote in his book, “Smith thought that Bush must be the coolest customer in the world. The whole time that he had been entertaining the speechwriters, he had known that the [24,000] troops were on their way in.” You would want him on your side playing blind-man’s bluff.

Bush: the sunshine of his smile. As 1989 ended, the president addressed the Catholic University of America annual dinner for the second time in three years. “Tonight I’m back again,” he told the audience. “Even though I know this isn’t what you have in mind when you preach about the Second Coming.” More than a thousand people had packed Washington’s Pension Building. “For those of you in the back of the room, I’ll try to speak up,” Bush said. “Cardinal Hickey warned me that the agnostics in this room are very bad.” Bush touted religious belief, service, devotion to higher learning, and fidelity to freedom, concluding, “God can live without man, but man cannot live without God.” The crowd popped a cork. Later that week Chriss Winston said that the president wanted to see me. I went to the small anteroom off the Oval Office where he crafted his “self-typed” letters. Bush thanked me for the Catholic University speech—“the kind of speech I like,” he said. “Anecdotes, humor, structure.” I paused. “It’s funny. You’re Episcopalian, I’m Presbyterian, and the audience was Catholic.” Bush laughed. “Well, we’re all on the same side,” he said.

Bush: stormy weather. Early that year I wrote an eyes-only—for mine—memo for the express purpose of blowing off steam. Its title: “Who Won the Election, Anyway?” Shortly after Bush’s inaugural, his defense secretary nominee, former Texas senator John Tower, began being pilloried for private impropriety—namely, that he liked to drink, not unlike other politicians, including his late fellow Texan and president Lyndon Johnson. Washington hypocrisy made only Tower a risk to national security. Instead of bashing Tower’s opposition, Bush praised the Senate for “looking at the allegations very carefully,” adding, “If somebody comes up with [new anti-Tower] facts, I hope I’m not narrow-minded enough that I wouldn’t take a look.” In my view, the perception that Bush wouldn’t fight led Democrats to believe that they could outface the GOP in the Budget Crisis of 1990, to which we will shortly turn.

Bush had been elected in 1988 on a conservative little guy vs. big guy plank. He felt it more real, I think, than sham. To him, Willie Horton was entirely legitimate—a metaphor for Democrats favoring criminal rights vs. victim rights. Disturbingly, some in our administration felt the issue bogus. Not quislings, exactly, they simply liked a me-too creed that hadn’t—couldn’t—elect a GOP president in our lifetime, before or since. Liking to win, Bush in 1988 showed with whom he stood. In 1989 he unveiled Reagan’s official portrait, saying, “For years our opponents were hoping to see President Reagan’s back against the wall here in the White House. But I don’t think that this is what they had in mind.” Bush also presented the National Academy of Engineering Awards, quoting Einstein: “Everything that is really great and inspiring is created by individuals who labor in freedom.” He promised brevity to the National Religious Broadcasters: “I know there’s a mention in the Bible about the Burning Bush, but I also know I’m not that hot a speaker.” Bush was stroking his 1988 base: creators, homeschoolers, small-business people, retirees.

In February 1990 the Sandinistas were voted out of power in free elections in Nicaragua. In Czechoslovakia workers risked imprisonment by passing faded copies of playwright-turned-politician Václav Havel’s manuscripts from one reader to another. In China students handed out handbills printed on mimeograph machines detailing the murder in Tiananmen Square. In October 1781 the British band at Yorktown had played “The World Turned Upside Down.” In less than two years, Bush had helped invert his world. In the Market Opinion Research poll, Poppy’s first four months registered 70 percent approval vs. Nixon’s 61, Reagan’s 67, and Ike’s 74. By mid-1990 his mid-60s monthly approval average swung between 52 and 76 percent. Gallup, ABC News / Washington Post, USA Today, and NBC News / Wall Street Journal showed like results. “Kinder, gentler” seemed to be wearing well.

On March 22, 1990, Bush showed a comic streak to shame Henny Youngman. At a news conference on the South Grounds of the White House, he confirmed a reported ban on broccoli aboard Air Force One, saying, with fists clenched and voice rising, “I do not like broccoli. And I haven’t liked it since I was a little kid, and my mother made me eat it. And I’m president of the United States, and I’m not going to eat any more broccoli!” This opened a national dialogue on Bush’s teenage eating habits—beef jerky, nachos, tacos, hamburgers, hot dogs, popcorn, ice cream, chili, pork rinds, refried beans, barbecued ribs, and cake—all gobbled like an excavator gulps dirt. Mrs. Bush remained a broccoli holdout, the president said—indeed, a “total totalitarian,” threatening to serve him a meal of broccoli soup and salad, a broccoli main course, and as the First Lady said, “finish with a little broccoli ice cream.”

That summer Bush taped a Fourth of July TV special from Ford’s Theatre, telling a story that President Lincoln loved. Two ladies were debating the merits of Honest Abe and Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy. The first said, “I think Jefferson will succeed because he is a praying man.” Second: “But so is Abraham.” First: “Yes, but the Lord will think Abraham is joking.” By turn, Bush launched Fitness Month on the South Lawn, quoting a fine golfer who often dieted but seldom exercised, Jackie Gleason: “a little traveling music.” He addressed the Red Cross, glad to serve as honorary chair, a reason “being that if my speech is a disaster, relief is close at hand.” He gloried that Barbara had already become the most popular First Lady, depending on your age, since Jacqueline Kennedy or Eleanor Roosevelt—“Everybody’s mother,” she said to explain her appeal. Increasingly, Bush feared he might have to repeal the pledge that helped make him president.

“Read my lips! No new taxes!” had been Bush’s campaign cry—and risk. In 1985 Congress passed the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act, mandating a zero federal budget deficit by 1991. Since his inaugural Bush had inherited a huge deficit, Congress had become even more wastrel, and budget deficit estimates for fiscal year 1991 had soared from $111 billion to $171 billion. That year began October 1, 1990. Unless Bush cut the deficit to at least $64 billion, Gramm-Rudman would slash every entry in the federal budget by a draconian 40 percent—defense, farming, education, the elderly. Bush was trapped. Growth had stalled, largely owing to Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan’s refusal to cut interest rates till the deficit shrank. Yet Poppy had vowed not to raise taxes. At the same time, Democrats refused to cut spending—moreover, could override Bush’s veto pen, and had. As 1950s television’s Chester A. Riley bayed, “What a revoltin’ development this is!”

In April 1990 Bush and Democratic leaders agreed to new revenue for the 1990 budget. “I mean to live by what I’ve said: no new taxes,” 41 said, publicly. His diary read differently: “If we handle it wrong, our troops will rebel on taxes.” Then ABC White House correspondent Brit Hume asked about taxes. “Well, I’d like it [the vow] to be more than a first-year pledge,” Bush said, tentatively. On June 25 he, Sununu, budget director Richard Darman, Treasury Secretary Brady, and Democratic dons met in closed session at Andrews Air Force Base—their aim, broader talks, with other members of each party. House Speaker Tom Foley, replacing Jim Wright, made Bush an offer: entitlement and budget reform, defense and domestic discretionary spending cuts—and new taxes—or risk Gramm-Rudman and continued deadlock. “The more he [Poppy] sat in on the meetings,” said Marlin Fitzwater, “the more he decided that regardless of the politics, regardless of the consequences, that he had to raise more money through taxation.”

Bush could have gone over Congress to the public, explaining his change of heart. Instead, he trusted the Democrat elite—we’ll cover you politically. “He did it out of good motives trying to get something done, as he said, to govern,” said Brit Hume. Finally, Bush said, “Okay, if I can say you agreed.” Foley and Senate leader Mitchell said fine; Democrats were almost always for new taxes anyway. Bush hoped a pact including new taxes would sire short- and long-term stability. Too late did he grasp the tax reversal’s effect on his credibility. In 1517 Martin Luther is said to have nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg, Germany, sparking the Reformation. In 1928 Calvin Coolidge announced on the White House bulletin board that he would not seek reelection: “I do not choose to run.” Darman wrote a two-sentence statement that Sununu edited, gave to Fitzwater, and had him put on the press office bulletin board—no cause or context about why overnight the White House was crying uncle.

For a time, breaking “No New Taxes” meant chaos. “The budget plan was successful in achieving a non-partisan [adverse] public reaction,” said GOP pollster Bob Teeter. “The President’s perceived handling of the budget crisis has caused much more disapproval than approval.” Later, it became a low-grade fever for much of 1991, dwarfed by Bush’s global élan. In 1992 the virus returned to help Ross Perot, making 41 seem just another pol. In 1990 I wrote as many as four fundamentally different drafts of the same budget speech in an afternoon. We were glad to have axed the pledge. We weren’t glad, but had been forced to do it. We would never do it again. (This pleased conservatives, not trusting Dems to cut spending.) We just wanted the damn thing done. For Bush’s writers, the broken pledge made the 1990 campaign more Kafkaesque than Reaganesque.

At a Detroit fund-raiser, Bush minimized progress toward an agreement. In Iowa the president said he had negotiated for eight months. “The American people didn’t send me here [sic] to play politics. They sent me here to govern. So I put it all on the table—and I took the heat.” In California he called his tax reversal “a serious response to a serious deficit”—and it might have been seen as such had he stayed on message, telling how the act decreed two dollars in spending cuts for each dollar in new taxes. (Ultimately, it didn’t happen.) Bush wrote me, “On tonight’s speech to political audience, better to not polarize until talks are over for better or worse.” He composed this text: “You know how much I want to get a real deficit package. I have composed etc. etc. but now is not the time for partisan rhetoric. Now is the time to get the job done etc. etc.” The etc. etc. would have been to inform people how a lower deficit could fuel prosperity—here, till America’s longest post–World War II recession began in 2007.

A budget agreement was announced September 30, 1990, raising the top federal individual income tax rate from 28 to 31 percent—a relatively minor, not major, hike. (Today’s top rate is 39.6 percent.) Some liberals opposed its spending cuts. As Bush feared, “the [conservative] troops rebelled,” having largely been ignored. On October 2 he gave a rare Oval Office speech on network television, saying, “This is the first time in my presidency that I’ve made an appeal like this to you.” Conditions had changed since 1988, Poppy said, a smaller deficit now a prerequisite for growth. Then House minority whip Newt Gingrich had changed as well. At Andrews he backed the deal. Now he pivoted, blasting it and taking most of the GOP House—for Bush, betrayal. “It was stunning to see how many fellow Republicans shot old George out of the saddle,” former Senate minority whip Alan Simpson told Bush writer–turned–U.S. News columnist Mary Kate Cary in 2014. “[It] brings tears to your eyes.” Gingrich Inc. wanted Democrats to further cut spending, deeming “No New Taxes” less political than theological. Only 32 of 168 Republicans backed the final package. It passed because 218 of 246 Democrats voted yes, liking what they saw.

That month I tried bipartisanship too, giving liberal New York Post columnist Phil Mushnick and his two young daughters a tour of the White House. Both girls sent thank-you notes, including Laura, age eight: “Dear Mr. Smith: Thank you for the wonderful tour. My sister enjoyed it, too. My father says you are a nice man for a Republican.” For months the cliché that the nice man in the Oval Office was more interested in foreign than domestic affairs had become consensus. The administration denied it, except that the cliché was true. Bush himself agreed in his diary on October 6: “There’s a story in one of the papers saying that I am more comfortable with foreign affairs, and that is absolutely true. Because I don’t like the deficiencies of the domestic, political scene. I hate the posturing on both sides.” Having broken the “taxes” pledge, Bush found their speeches no-win to give.

Other speeches were easier, even that summer’s Nixon Library dedication at Yorba Linda, California. On one hand, Nixon’s once protégé felt betrayed by the 1972 Watergate burglary of Democratic Party headquarters—then, far worse, a cover-up by Nixon officials to protect those party to the crime. On the other, Bush felt gratitude for Nixon’s past loyalty and shared his belief that “Americans elect a president for foreign policy,” enormously respecting the thirty-seventh president’s. Admiring Nixon yet appreciating Bush’s attitude, I requested and got the speech. In the Oval Office, we discussed it. “This is sensitive,” he said. “I owe Nixon an awful lot, but he lied to me. Try to be gracious, not obsequious.” Back at the computer, I squared a circle as I walked Bush’s line.

On July 19, 1990, more than seventy-five thousand people sat under a cerulean blue sky: union members, other blue-collar workers, small-business owners, housewives, retirees, farmers—all grandly unhip and unboutique. Nixon had grown up among them, as had I. Presidents Ford and Reagan spoke woodenly and wonderfully, respectively. Bush then rose to introduce Nixon, whereupon John Sununu, sitting in front of me, turned and jibed, deadpan, “Smith, he had better be good.”

Bush observed that next-day visitors would be the first to enter America’s tenth presidential library. “They will note that only FDR ran as many times as Richard Nixon—five—for national office, each winning four elections, and that [at that time] more people [had] voted for Richard Nixon as president than any other man in history. They will hear of Horatio Alger and Alger Hiss; of the book Six Crises and the seventh crisis, Watergate”—Bush’s was the only of the day’s four presidents to mention it. “They will think of Checkers, Millie’s role model. And, yes, Mr. President, they will hear again your answer to my ‘vision thing’—‘Let me make this perfectly clear.’”

Bush segued to Nixon’s family—“Think of his mother, a gentle Quaker”—and Nixon’s intellectual complexity—“Knowing how you feel about some intellectuals, Mr. President, I don’t mean to offend you.” He noted how Nixon “‘came from the heart of America’—not geographically, perhaps, but culturally”—then cited RN’s domestic policy from ending the draft via revenue sharing to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Above all, said Bush, a visitor would recall Nixon “dedicating his life to the greatest cause offered any president”—peace among nations. In Moscow “Richard Nixon signed the first agreement to limit strategic nuclear arms.” In the Middle East, “he planted the first fragile seeds of peace.” In Vietnam he pursued “a quest for peace with honor.”

“Even now, memories resound of President Nixon’s trip to China—the week that revolutionized the world,” said one sinophile of another. “No American president had ever stood on the soil of the People’s Republic of China. As President Nixon stepped from Air Force One and extended his hand to Zhou Enlai, his vision ended more than two decades of isolation.

“‘Being president,’ he often said, ‘is nothing compared with what you can do as president,’” Bush concluded. “Mr. President, you worked . . . to help achieve a generation of peace.” As democracy’s tide swept the globe, Nixon could take pride that history would say, “Here was a true architect of peace.”

That night ABC TV’s Nightline gathered several commentators to dissect the ceremony. Critiquing the speeches, New York Times columnist William Safire proclaimed Bush’s “the best. It touched every base.” Presumably Sununu was pleased.

Fourteen days later—Thursday, August 2—Iraq’s Saddam Hussein invaded next-door Kuwait and dubbed it his nation’s nineteenth province. In 1940, when Churchill became prime minister with the Nazis at Britain’s door, he wrote, “I felt as if . . . all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial.” Bush must have felt so now—and that a bully had kicked sand in freedom’s face. He reacted quickly, his instinct more sure than in the budget process. As if Providence were in Aspen, Colorado, to write a coda, Margaret Thatcher was with Bush at a conference there. “Now, George,” she said, famously, “this is no time to go wobbly.”

On August 8 Bush delivered an unwobbly speech, written by Mark Lange, in the Oval Office. “In the life of a nation, we’re called upon to define who we are and what we believe. Sometimes these choices are not easy,” Bush said. “But today as president, I ask for your support in a decision I’ve made to stand up for what’s right and condemn what’s wrong, all in the cause of peace.” At his behest elements of World War II’s famed Eighty-Second Airborne Division and key units of the U.S. Air Force were taking up defensive positions in Saudi Arabia. Iraq proposed a deal to keep half of Kuwait. Bush rejected it, forging a UN armada—Operation Desert Shield. Iraq must withdraw “completely, immediately, and without condition”; its “aggression must not stand.”

On Monday, August 20, Bush traveled to Baltimore to address the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) and review the lessons of the last eighteen days “that speak to America and to the world.” First, aggression must, and would, be checked—so we had sent U.S. forces to the Middle East reluctantly but decisively. Second, by itself America could do much. With friends and allies, America could do more—so Bush was forging the armada to oppose unprovoked aggression. The third lesson, said Bush, “as veterans won’t surprise you: the stead fast character of the American will. Look at the sands of Saudi Arabia and the waters offshore—where brave Americans are doing their duty—just as you did at Inchon, Remagen, and Hamburger Hill.”

1. George H. W. Bush, thirteen, in 1937 at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. As president, returning in 1989, he said, “I loved this school, this place.” GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

2. Bush (bottom), with unidentified seaman, moments after being rescued by the submarine USS Finback, September 2, 1944. Bush was shot down, and two crewmates killed, when the Japanese attacked their plane near Chichi Jima. GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

3. Babe Ruth (left), dying of throat cancer, presents a manuscript copy of the book The Babe Ruth Story to Bush, captain of Yale University’s varsity team, before a 1948 game at Yale Field. OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PHOTO

4. U.S. senator Prescott Bush and wife Dorothy supplemented each other’s strengths. He taught son George self-reliance. She taught him a becoming modesty. Each taught faith, tenacity, and honor. GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

5. In 1948 Bush left Connecticut to become an independent oil man in Texas. Here he is shown examining equipment on an oil rig with a worker. He entered politics only when financially self-sufficient. GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

6. Richard Nixon was Bush’s first mentor, campaigning for him for Congress and U.S. Senate. In 1971 Bush became the president’s UN ambassador—the first step in his impressive foreign policy education. GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

7. In 1971 Democrat, ex-Texas governor, and Bush rival John Connally became Nixon’s secretary of the treasury. Here Connally, to Bush’s right, makes a point aboard Air Force One. Nixon listens to rear. RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

8. In 1980 Ronald Reagan won the GOP presidential nomination, chose Bush as vice president, and became a beloved and historic president. As veep Bush earned the Gipper’s trust, crucial to his own presidential election victory in 1988. GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

9. After being sworn in as president, Bush delivered his January 20, 1989, inaugural address. The new president paraphrased from Saint Augustine: “In crucial things, unity; in important things, diversity; in all things, generosity.” GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

10. Amid rain in Budapest, Bush tore up author’s speech and briefly ad-libbed on July 11, 1989. Listening by intercom in DC, Curt Smith did not know the reason for his public flogging. Back home, Bush sent him this photo, signed, “It’s raining in Budapest, I’ll wing it, George Bush.” REUTERS

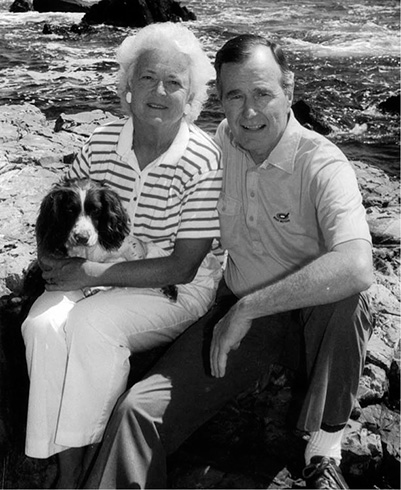

11. George and Barbara Bush with English springer spaniel Millie on August 8, 1989, at Walker’s Point, estate and home bought and built in the early twentieth century by Bush’s family in Kennebunkport, Maine. It became Bush’s Summer White House. GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

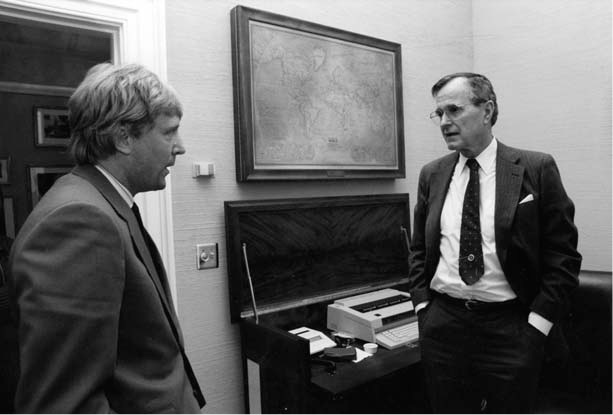

12. The author, on first floor of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building (née Old EOB). Next to the White House, it is noted for extremely high ceilings. Since 1969 the writers’ corridor in this former State, War, and Navy Building has been called Writers’ Row. COURTESY OF AUTHOR

13. On December 1, 1989, Bush held his first meeting as president with Soviet Union general secretary Mikhail Gorbachev on USS Forrestal off Malta. Bush also spoke to five thousand sailors, quoting Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s D-day address. GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

14. In late 1989 Smith was summoned to Bush’s office to discuss the response to his speech at the Catholic University of America dinner. It had concluded, “God can live without man, but man cannot live without God.”

OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PHOTO

15. On December 19, 1989, no one knew when the president hosted speechwriters in his residence that he had already sent forces to capture Panama’s drug duce Manuel Noriega. Only the author, to Bush’s left, heard him say, “I feel a thousand years old.” OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PHOTO

16. When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in August 1990, Margaret Thatcher told Bush, “Now, George, this is no time to go wobbly.” In March 1991 he gave her the Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian award. Smith (left) wrote Bush’s speech about “the greengrocer’s daughter.”

OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PHOTO

17. In November 1990 Mrs. Thatcher was ousted from power by a coup d’etat by her Conservative Party. That week the author got her response to a letter he had written with several other writers vowing support for the Iron Lady, who had shaped a nation to her will. COURTESY OF THE THATCHER FOUNDATION

18. At Thanksgiving 1990 President and Mrs. Bush flew to Saudi Arabia to meet with troops of the greatest allied armada since World War II. Their mission: to drive Saddam Hussein from Kuwait. Bush told them, “This aggression will not stand.” GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

19. On March 6, 1991, Operation Desert Storm complete, Bush addressed a joint session of Congress. The president stood, as Edmund Burke once said of a peer, at “the summit. . . . He may live long. He may do much. But he can never exceed what he does this day.” GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

20. The president boarding Marine One, the presidential helicopter. In March 1991 he left the White House for a weekend at the presidential getaway at Camp David. Aides held signs saying “91,” meaning Gallup’s historic high 91 percent approval rating. GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

21. In spring 1991 President Bush gathered speechwriters and other aides in the Oval Office to discuss what the administration should do next. The quest for a “domestic Desert Storm” proved elusive as legislative proposals and the economy stalled. OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PHOTO

22. On June 8, 1991, the commander in chief was saluted by the armed services which that year helped free a nation. The parade to hail the victorious Gulf War was held on Constitution Avenue in Washington and attracted a half a million spectators. GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

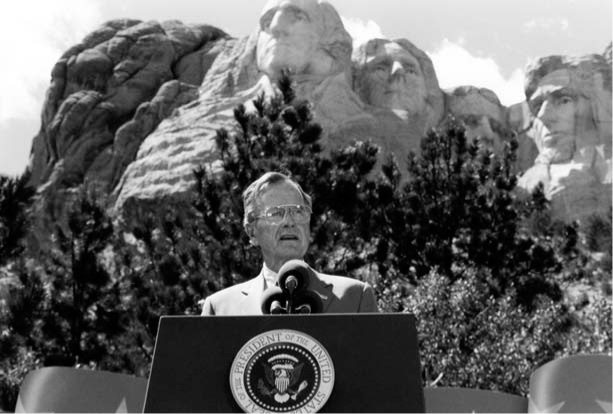

23. Bush hated politics’ incivility. What he liked was on display on July 4, 1991, at Mount Rushmore, showing how four nation builders—Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and TR—their likenesses completed half a century earlier, embodied America’s core. GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

24. The 1992 campaign hung over a November 1991 luncheon of Bush with presidential speechwriters. “We need a formulation for placing the blame on Congress for the economy without losing their support,” the president said. It was like squaring a circle. OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PHOTO

25. Friends of Bush died at Pearl Harbor in 1941. Half a century later, he gave perhaps his presidency’s most emotional speech there. “Every fifteen seconds a drop of oil still rises from the [sunken] Arizona and drifts to the surface,” he said, voice breaking. “It is as though God Himself were crying.” GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

26. Christmas at the White House was magical. In 1992, 120,000 visitors saw decorations that included thirty trees with icicles, tinsel, and white lights; needlepoint; toy trains; eleven-foot-tall toy nutcracker soldiers; and a gingerbread house turned Santa’s Village. OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PHOTO

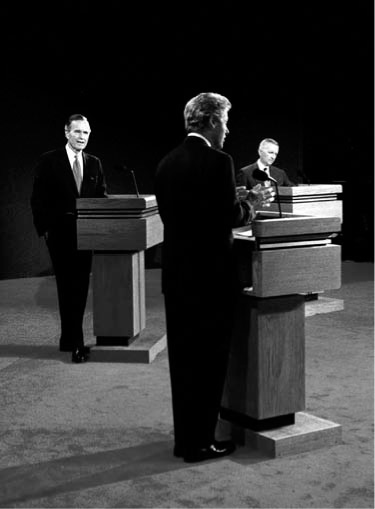

27. Improbably, Bush lost the 1992 election, getting only 37.5 percent of the vote. On October 19 he debated victorious Democratic nominee Bill Clinton (center) and third-party candidate H. Ross Perot. Perot lured 18.9 percent of the vote, most of it from Bush. GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

28. Five U.S. presidents—the current (Clinton), three past (Bush, Carter, and Ford), and one future (George W. Bush)—shared November 1997’s dedication of the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum at Texas A&M University at College Station, Texas. GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

29. On June 12, 2009, to honor two crewmates killed when the Japanese destroyed their Avenger plane in 1944, Bush did a tandem parachute jump in Kennebunkport with the U.S. Army Golden Knights to mark his eighty-fifth birthday. Amazingly, he encored at ninety in 2014. GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

30. The former First Couple at the Bush Presidential Library and Museum in 2002. In 2013 President Obama invited them back to the White House for the five thousandth daily Point of Light Award, an honor given by the famed volunteer program begun by Bush. GEORGE BUSH PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY FOUNDATION. Chandler Arden, photographer

31. In 2001 Bush learned that the author and his wife were about to adopt two very young children from Ukraine, a country that the president, helped by others here and abroad, had helped to liberate. Unsolicited, he wrote each child a letter that they received upon arriving in America. COURTESY OF PRESIDENT GEORGE H. W. BUSH

A fourth lesson concerned the future size of the U.S. armed forces: smaller because “the threat to our security is changing,” said Bush, with American defense capacity greater—“a lean, mean fighting machine.” When it comes to national defense, “finishing second means finishing last,” he argued, noting that more than half of all VFW members fought in World War II. “Half a century ago, the world had the chance to stop an aggressor, and missed it,” the president said. “I pledge to you: Unlike isolationists here and abroad, we will not make that mistake again.”

This was the first speech in which Bush likened Hussein to Hitler. It wasn’t easy. Bush’s writers, like the president, tried to include the comparison, prompting the National Security Council to erase it, at which point writers reinstated it. In this speech, I put it in, the NSC took it out, then Bush ad-libbed it—all in the name of exquisitely named reconciliation. Next month he spoke to Congress, setting four immediate goals: “Iraq must leave Kuwait . . . Kuwait’s legitimate government must be restored. The security and stability of the Persian Gulf must be assured. And American citizens abroad must be protected.” Bush also foresaw a new world order. More tangibly, Congress okayed the use of military force.

For 166 days Bush tried to peacefully remove Hussein from Kuwait. The president knew what he meant to say and said it. I often arrived at the White House, checked my mailbox, and found page after page of text “self-typed” by him the previous night. I retyped it; fixed grammar, spelling, and punctuation; used the president’s text as the first draft; and seldom deviated from its spine. Bush was involved at every level of Gulf War speech preparation. By contrast, his explanation of the budget process in the 1990 midterm campaign was considerably less thorough. “The budget agreement was as good as we could get,” he said. “It would have been better with a GOP Congress.” Looking back, it would have been best if Congress didn’t treat fiscal discipline like malaria or beriberi.

With the election over—essentially a wash in each house—the president turned wholly to foreign policy, i.e., the Persian Gulf. He flew in Air Force One with Mrs. Bush and General Norman Schwarzkopf, head of U.S. Central Command, escorted by F-15 Eagle fighter jets, to spend Thanksgiving Day with U.S. troops stationed in Saudi Arabia. As White House Ghosts relates, Bush found the day’s remarks, written movingly by McNally, too personal. “Dave,” he asked Demarest, “what are you trying to do to me?”—he was afraid he would break down. The communications head began to delete text. Bush joined him. Next day editing continued. Finally, Marines encircling Bush, Demarest saw the light: “The power of him [Bush] being with the troops really was the message.” Less was more.

Bush returned to an America less of war fever than the sheer intention to see war through—January 15, 1991, was the UN-set deadline for Hussein to withdraw his troops from Kuwait. “No one wanted war less than I, but we will see it through,” Bush wrote in his diary. On Sunday, January 13, he added, “It is my decision—my decision to send these kids into battle, my decision that may affect the lives of innocence [sic]. . . . It is my intention to step back and let the sanctions work. Or to move forward. . . . I know what I have to do. . . . This man is evil, and let him win and we rise again to fight tomorrow,” as after Munich, appeasement bred World War II.

“There is no way to describe the pressure,” said the man who, almost killed at twenty, knew war perhaps as well as any U.S. president. The bombing would begin at 7 p.m. on January 16. The president would address the nation two hours later. Dan McGroarty wrote two initial drafts. Bush—saying, “I want to write this speech myself”—did, referencing parts of McGroarty’s text. The president’s draft asked the question, “Why act now?”

He answered, “While the world waited, Saddam Hussein systematically raped, pillaged, and plundered a tiny nation, no threat to his own. . . . While the world waited, Saddam sought to add to the chemical weapons arsenal he now possesses, an infinitely more dangerous weapon of mass destruction—a nuclear weapon. And while the world waited, while the world talked peace and withdrawal, Saddam Hussein dug in and moved massive forces into Kuwait.”

Five months earlier Hussein had started this “cruel war against Kuwait,” Bush said. “Tonight, the battle has been joined.”

At 10:45 that night, Bush again wrote in his diary: “I am about to go to bed. I didn’t feel nervous about it at all. . . . I knew what I wanted to say, and I said it. And I hope it resonates.”

Victory would ensure it did.