MOUTH OF THE LION

THE VLADIMIR RODRÍGUEZ LAHERA AND MIGUEL ROCHE STORIES probably would never have been known outside of a small CIA circle—and soon forgotten by nearly all—had Laddie not traveled to Mexico City a month before defecting.

Under diplomatic cover, he went there from Havana to meet clandestinely with a group of Salvadoran Communist Party leaders. Patiently he waited, expecting to hear the password “Mauricio” that would authenticate them as Cuban assets. But they never arrived. The work of field operatives is often like this: planning for meetings that fail to materialize, whiling away days at a time waiting for a phone call in shabby hotel rooms in faraway cities.1

He lingered in the Mexican capital from March 14 to 23, 1964. It was his first trip outside of Cuba, and he was delighted to make the best of it at the DGI’s expense. Meetings with Nicaraguan revolutionaries were arranged, other operational tasks carried out; otherwise, he mingled with colleagues at the DGI Center. It operated out of the consulate building, adjacent to the embassy, on the same square-block compound in the downtown Condesa neighborhood. Once he was in CIA hands a month later, that experience assumed critical new importance.

Laddie’s knowledge of the Center’s personnel and procedures made him a figure of enduring interest in investigations into John F. Kennedy’s assassination. This is why virtually all of his CIA files were declassified in the 1990s under the legislated authorities of the Assassination Records Review Board that was established to make publicly available all federal government records considered relevant to the assassination. Rodríguez Lahera was important because he and Lee Harvey Oswald dealt with some of the same Cuban intelligence officers at the DGI’s Mexico Center.

Kennedy’s assassin went to the Cuban consulate on three occasions while in the Mexican capital between September 27 and October 2, 1963, seeking a visa to travel to Cuba. Laddie was at the Center six months later, and was already familiar with its operations because of his work at DGI headquarters. He was a unique and reliable source of information about one of the most vexing matters still under scrutiny by the Warren Commission. Could Cuban intelligence have had a hand in the president’s assassination? Chief Justice Earl Warren and six other American notables were in the late stages of their investigation into Kennedy’s death when Laddie defected, preparing to issue their much-maligned report the following September. CIA considered Laddie such a sensitive source, however, that he was shielded from commission staff. He was not interviewed, nor was Swenson. Worse, the most valuable information he brought that was relevant to the investigation was not fully aired or analyzed at the time. Notably, Laddie was convinced that Fidel had lied when he publicly denied any knowledge of Oswald prior to the assassination on November 22, 1963.2

In two speeches over the next few days after Kennedy’s death, Castro insisted that he had known nothing about the assassin. By nightfall on the day the president died and Vice President Johnson had been sworn in to succeed him, Oswald’s Marxist convictions, defection to the Soviet Union, and pro-Cuban passions and activism were reverberating in the news media. Castro knew he needed to preempt the inevitable charges that Cuba had somehow been involved in a conspiracy. So, speaking of Oswald on the evening of November 23 from a Havana television studio, Fidel was unequivocal: “We never in our life heard of him.”

Knowing the stakes were dangerously high, Castro had gambled. Few people could credibly contradict him. Only a handful of Cuban officials had the knowledge to refute their leader, and who would dare? No one, of course, anticipated that Laddie would defect a few months later. As in similar instances over the years when the pressure was intense, Fidel calculated that through bluster, bombast, and well-crafted lies, endlessly retold, he would be believed. The government’s propaganda machine—and DGI active measures campaigns that echoed his position—were rolled out almost immediately. The lie was perhaps an understandable retreat from the heat of the moment, but it has only compounded the doubts: What else was Fidel hiding?

In early May 1964, Swenson reported up the line what Laddie knew about Fidel’s deception, condensing it into just a few words. Hal added no commentary and made no effort to highlight the information. Oddly, he did not consider it important, and there is no evidence in the declassified records that anyone else in CIA did either. No one informed Cuba specialists in the analytic directorate. As a result, my predecessors there did not include any details in the sensitive intelligence publications they drafted for Washington policy audiences. The two subsequent congressional investigations of the Kennedy assassination and independent researchers also overlooked the anomaly. Fidel’s deception was buried away in the Rodríguez Lahera archive, where it remained unexamined—until now.

LADDIE KNEW THE WORKINGS of the Mexico Center well. With at least ten case officers, it was the largest Cuban Center in the world. CIA believed that even the gardener worked as an intelligence asset. Laddie revealed that the DGI also staffed busy consulates in the Mexican gulf coast ports of Veracruz and Tampico, and in Mérida, the principal city on the Yucatán peninsula. The Cubans enjoyed “quite a lot of freedom of movement and action in Mexico in those days,” Helms’s deputy told the Church Committee.3

Laddie knew Manuel Vega Peréz, the corpulent Center chief, and his deputy, Rogelio Rodríguez López. They were among Piñeiro’s most ruthless and proficient operatives, handpicked by Fidel. Two independent sources told CIA handlers that in February 1964, the two masterminded an assassination attempt against Anastasio Somoza, then commander of his country’s National Guard. It was to be carried out by Nicaraguan illegals under Cuban direction. That attempt failed, or never coalesced—the declassified record is incomplete—but the DGI’s merciless hunt for the archenemy continued. Vega and Rodríguez López, and their accomplices, could claim no credit for the ex-dictator’s fiery annihilation years later, but their efforts were probably as seriously planned.4

Laddie identified other Mexico Center intelligence officers. In Havana, he had known Luisa Calderon, a vivacious and attractive young woman, before the DGI transferred her to the Mexico Center. A senior DGI official at headquarters believed “hers was a peculiar case,” and Laddie knew enough about her to agree.

She went into seclusion immediately after Kennedy’s assassination. When she returned permanently to Cuba a few weeks later, Laddie said that Calderon continued to be paid “a regular salary by the DGI even though she has not performed any services.” She was living in an expensive Havana neighborhood. He thought she may have had dealings with Oswald.5

Swenson reported that Laddie “had no personal knowledge” of Kennedy’s assassin, though he had learned from Vega about Oswald’s second and third visits to the Cuban consulate. They would have been memorable to all within earshot.

In 1978, Silvia Duran, the Mexican receptionist there told staff of the House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations—investigating the deaths of President Kennedy and Martin Luther King—that Oswald created angry, boisterous scenes when denied a visa. Eight Cubans—including Fidel—were also interviewed by committee representatives.6

Two of them remembered Oswald’s visit vividly. Vega’s replacement, the incoming Center chief, DGI officer Alfredo Mirabal, told the committee that each of Oswald’s confrontations lasted from fifteen to twenty minutes. Cuban consular officer Eusebio Azcue said he argued with Oswald, “violently or emotionally.” “We never had any individual so persistent.” When refused a visa during his last visit, Oswald slammed the door in a rage as he departed.7

He was a baffling case for the Cubans. Duran remembered how hard he tried to convince them he “was a friend” of the revolution. Supposedly he carried a book of Lenin’s writings under his arm when he appeared. He also carried a packet of letters, documents, press clippings, and membership cards. Oswald had never joined the American Communist Party but brought a forged identification claiming that he had done so. He showed the Cubans that he was a legitimate, card-carrying member of the New York–based Fair Play for Cuba Committee. It was known by the FBI to be funded and manipulated by the DGI, although Cuban officials have denied that.8

Oswald tried to create an unauthorized branch of the Fair Play group in New Orleans, but he, his Russian-born wife, Marina, and the fictitious A. J. Hidell were its only members. Hidell—it rhymed with Fidel—was also the alias Oswald used to purchase the rifle used to kill Kennedy. A DGI captain who was among the officials monitoring the House committee during its representatives’ visits to Havana volunteered that the “A” in the Hidell name was short for Alejandro, Fidel’s nom de guerre during his insurgency. The Cuban commented, “I think it was well chosen.” How the captain knew what the initial referred to has never been explained.9 Oswald had been enthralled with Fidel since his late 1950s service at the El Toro Marine Corps Air Station in southern California. It was there, just before Christmas 1958, that Nelson Delgado, a Brooklyn-born Puerto Rican, struck up a friendship with him. Delgado was one of the few people who ever thought of the acerbic, unpredictable Oswald as a real buddy. He told the Warren Commission: “We started talking . . . got to know each other quite well.” The glue between them was the attraction they felt for Castro and the guerrilla struggle he was then in the final week of waging against Batista. Delgado said they had “many discussions regarding Castro.” Oswald “actually started making plans . . . how to get to Cuba. . . . He started studying Spanish . . . and kept asking me how he could go about helping.”10

“I didn’t know what to tell him,” Delgado remembered, so “the best thing I know was to get in touch with the Cuban embassy . . . I told him to go see them.” Delgado believed Oswald reached Cuban government representatives in Los Angeles. “After a while he told me he was in contact with them. . . . He was telling me there was a Cuban consul . . . and he started receiving these letters.” Later Delgado remembered that Oswald had a civilian visitor at the marine base whom he suspected was a Cuban. “They spent about an hour and a half, two hours talking.” It appears that reports about these alleged contacts found their way into the DGI’s case files on Oswald.

Batista was ousted on January 1, 1959, so it was too late for Oswald to find his way to Cuba to fight as a foot soldier in Fidel’s insurgency. An alternate plan materialized. Delgado recalled that they mused about volunteering as guerrilla fighters in other Caribbean countries. They talked about “how we would like to go to Cuba and . . . lead an expedition to some other islands and free them too.” For Delgado, their bravado may have been mostly idle, romantic fantasizing; for Oswald, it reflected his authentic militance and desire to abandon the bourgeois America he despised. In October 1959, he defected to the Soviet Union.

His infatuation with Fidel and Cuba endured. Marina first noticed it during their courtship in Minsk, today the capital of independent Belarus. Oswald was incensed when the CIA’s brigade of Cuban exiles landed at the Bay of Pigs. He took Marina to see a Soviet film about Cuba, telling her he considered Fidel “a hero.” Authors Jean Davison and Gus Russo wrote that he sought out Cuban students in Minsk.11

Back in Texas and Louisiana after redefecting in 1962, Oswald’s interest in his hero grew. He hung a picture of Fidel on the wall of his apartment in New Orleans. He mused about naming the couple’s unborn first child Fidel. Absurdly, he tried to talk Marina into helping him hijack a plane to Cuba so, she recalled, he could fight for “Uncle Fidel.” He read copious amounts of print propaganda about his idol and was adept at repeating it. Translated speeches by Castro, photographs of him, booklets, and other published materials extolling the revolution were found among Oswald’s possessions after his arrest.12

At the consulate in Mexico City, he struggled to persuade the Cubans of these revolutionary bona fides and brandished a photo of himself from a New Orleans news story published a few weeks earlier. He had been arrested after a street altercation with Cuban exiles as he was passing out pro-Castro leaflets. Marina remembered that he was proud of the disturbance he had created and the night spent in jail as a result. She told the Warren Commission that he “was smiling” when he came home the next morning. “It was advertising,” she said. “He wanted to be arrested.” She believed he had staged the event just so he would have proof of his militance to show the Cubans. When he realized that embassy representatives were not impressed, however, Oswald denounced them. They were just “bureaucrats.” He, in contrast, “had been in jail for the Cuban Revolution.”

The fixation was especially strong during the summer months the Oswalds spent in New Orleans, just before his Mexico trip. “Fidel Castro was his hero,” Marina told the House committee. “[H]e was a great admirer . . . he was in some kind of revolutionary mood . . . he would be happy to work for Fidel Castro’s causes.” Oswald’s “devotion and ardor for Cuba knew no boundaries,” according to Kennedy assassination expert Vincent Bugliosi.13

In Mexico, Oswald told the Cubans that he had defected and lived in the Soviet Union for two and a half years. He had appeared on New Orleans radio and television programs professing Marxist beliefs and proclaiming that “Cuba is the most revolutionary country in the world today.” He had demonstrated in the streets of Dallas when he lived there, wearing a handmade placard that read “Hands Off Cuba! Viva Fidel!” He may have told the Cubans that he had learned about the U-2 spy plane he observed during military duty at an American air base in Japan.

All of that would have made him of interest to the DGI. In the universal language of intelligence, Oswald was, therefore, a classic walk-in, a voluntario, a defector when he showed up at the consulate. He wanted to be useful to the bearded man he idolized. He was eager to take up arms for Fidel. Marina was asked if Oswald often spoke about the Cuban revolution. “Yes, when Lee obtained a rifle, I guess that is somehow in my mind associated with some kind of revolution.”14

Oswald purchased the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle he used to kill Kennedy on March 12, 1963. He first fired it with homicidal intent on April 10, against retired army Major General Edwin Walker, an extreme right-wing, anti-Castro agitator who had demanded just days earlier that Kennedy “liquidate the scourge that had descended on Cuba.”15 The shot fired at the general, sitting in his Dallas home office after dark, missed his head by a fraction of an inch. So, Marina, who knew her husband better than anyone, was correct: Oswald’s purpose for buying the rifle was to adopt the persona of a worthy guerrilla fighter. By killing Walker, he would be aiding Fidel’s cause by eliminating a vitriolic enemy of the revolution. He would become one of Fidel’s warriors.

From the Soviet Union, Oswald had written his brother Robert that “in the event of war I would kill any American who put a uniform on in defense of the American government—any American.” Michael Paine, a young man who knew the assassin in Dallas, told the House committee that it was “Oswald’s belief that the only way injustices in this society could be corrected was through a violent revolution.” Paine later also said that “Lee wanted to be an active guerrilla in the effort to bring about a new world order. . . . There’s no doubt in my mind that he believed violence was the only effective tool.”16

Marina snapped photos of her husband in the backyard of a house they rented in Dallas before moving to New Orleans. He is posed as a militant, dressed in black, armed with the Mannlicher-Carcano. A holstered pistol rests on his hip; it is the one he used to kill Dallas policeman J. D. Tippit less than an hour after he murdered Kennedy. He clutches recent issues of the American Communist Party’s weekly The Worker and The Militant, a Trotskyite publication. He had subscribed to both more than a year before; they were his preferred means of keeping up with news from Cuba.

In the photo his face is calm and determined, with the hint of a satisfied smile. In her book on the Oswalds, Priscilla Johnson McMillan described his expression as one of “sublime contentment.” He appeared to be a young American equivalent of the thousands of his Latin American contemporaries then enrolled in Cuban guerrilla training schools, eager to take up arms for Fidel. A few days after Kennedy’s death, Marina told the Secret Service that Oswald had planned to send a copy of one of the photos to The Militant “to show he was ready for anything . . . even if it involved the possible use of arms.”17

Getting to Cuba was his priority. Oswald told Duran at the consulate in Mexico he wanted to “spend some time” on the island. On the bus trip to the Mexican capital, he had chatted with another passenger and remarked that he planned “to see Castro.” The Warren Commission concluded that he most likely “intended to remain in Cuba.” Marina thought so too; she testified that, when he left for Mexico City, “He does prefer to go and live in Cuba . . . I honestly did not expect to see him again.” To the disturbed twenty-three-year-old, revolutionary Cuba was the utopia he was dreaming of.18

LADDIE’S FAMILIARITY WITH THE MEXICO CENTER and what he had learned about Oswald’s visits at first came up only in passing with Swenson. Those details did not seem as important to Hal as the operational information he was accumulating about Cuban subversion in Latin America. It would not be long, however, before others began connecting the Mexico City dots. Within about a week of his arrival, Laddie came to the attention of Angleton’s Counter-intelligence Staff. Ray Rocca, then chief of its Research and Analysis Division—he described it as “a counterintelligence laboratory”—was briefed in on the case.19

Rocca and Angleton were backing up Helms, the Agency’s chief liaison with the Warren Commission. It was because of their regular dealings with the commission staff that they knew what Swenson at first did not: dissecting Oswald’s Mexico sojourn was still a priority. A commission counsel later stated those concerns succinctly. They were focused on whether Oswald was “prompted by, or a part of a conspiracy originating in Cuba, or with supporters of Cuba.” There was “some considerable disquiet,” he said, about that supremely troubling possibility. With Swenson’s early debriefing reports in hand, Angleton’s staff began to wonder if the newly arrived defector had fresh information that might implicate Castro.20

The hard-line Rocca would have loved nothing more. He was a stocky, gruff professional who joined the Agency at its inception in September 1947. Unlike his boss Angleton, “Rock,” as he liked to be called, was not inclined to froth up fantasy conspiracies or lapse into spasms of paranoia imagining KGB moles burrowed in at Langley. But he was loyal to Angleton, quitting the CIA career he loved in solidarity when his chief was compelled to resign in 1974.

On Friday, May 1, Rocca drafted a dozen questions for Swenson to use in a targeted debriefing of the defector. Most important, he wanted answers to these three:

Was Lee Harvey Oswald known to the Cuban intelligence services before 23 November 1963?

Were the Cuban services using Oswald in any agent capacity, or in any other manner before 23 November 1963?

Was any provocative material deliberately fabricated by the Cuban services or others and sent to the United States to confuse the investigation of the Oswald case?21

Responses, crafted by Swenson, were in hand within days. Laddie did not know if Oswald had been used by the DGI. With respect to the third question, Hal reported that “the only possible fabrication known by source was the specific denial (by Castro) . . . of any knowledge of Oswald.” There was no elaboration, and none was requested.22

But tensions within an elite circle in Langley soared over the response to Rocca’s first question. Swenson reported that Laddie knew Oswald had visited the consulate and that “before, during, and after the visits he was in contact” with the DGI. This ground-shaking allegation was never adequately clarified. Laddie believed there had been sustained Cuban engagement with Oswald.23

If the Warren Commission was informed of that information, it would have been propelled into terrifying new territory. The possibility of a Cuban conspiracy with Oswald would have received much greater attention. Even inconclusive but suggestive evidence—or, as CIA analysts expressed it in a sensitive report, the “imputation” of a Cuban hand in the assassination—would have exploded in Washington like Fourth of July fireworks on the Mall.24

It could not possibly stay secret for long. Congress and the American public would know soon enough, and war drums would begin sounding. Punitive military action against Castro might be inevitable. CIA had been reporting regularly about the trip-wire Soviet military force of several thousand that remained on the island. There was no doubt in Washington policy circles that armed conflict with Castro could easily explode into another superpower confrontation.25

No one had been more worried in late November 1963 than Cuba’s leaders. Laddie told Swenson how his old service went into a virtual lockdown the afternoon of November 22, after news of Oswald’s arrest was broadcast. Centers were ordered to package their classified information, separating out top-secret files, and to await further guidance. Travel by headquarters officers and diplomatic pouch deliveries were suspended. Personnel were instructed to stay in or close to their offices “so they could be reached immediately.” Piñeiro’s deputy held a meeting with National Liberation officers instructing them to prepare a system of coded communications with their agents overseas. A reliable spy in the Cuban government told the Agency that diplomatic missions abroad were ordered to be certain there “were no compromising documents on the premises.” Havana was worried that DGI Centers might be targeted by CIA for surreptitious entry.26

As was his custom when a crisis was gathering, Fidel took to the airwaves. He delivered three speeches in the days immediately following Kennedy’s assassination. (Transcripts of only two have survived outside of Cuba.) The first lasted two hours, delivered from a Havana television studio on Saturday night, November 23, a little more than a day after Kennedy was killed. By then Oswald had been charged with the murders of the president and Officer Tippit.

Fidel was cautious, often eloquent—and profoundly worried. The Monday-morning CIA Daily Summary—a sensitive publication devoted solely to Cuba— reported that the speech reflected Castro’s “apprehension that US policy toward him may now become even tougher.” The Central Intelligence Bulletin, a Top Secret global intelligence daily for senior policy readers provided more comprehensive coverage. Fidel had described the assassination as a “dangerous Machiavellian plot against Cuba. . . . We must be cautious and vigilant and alert.” He said Kennedy’s death could only benefit “ultra rightist and ultra reactionary sectors . . . now breaking loose in the United States.”27

Che Guevara expressed alarm in a speech on November 24. He warned that “the peace of the world will be threatened for years to come.” The most “unscrupulous, ferocious, and warlike” forces were being unleashed. Characteristically lapsing into his signature theme, he stressed that “revolutionary ferment in Latin America is reaching a new climax . . . the people are going to conquer power in whatever manner necessary.” Hoy, the Cuban Communist Party newspaper at that time, declared that a “dirty maneuver” was afoot, “aimed at making Cuba the perpetrator of the crime.” That summarized the fears of the leadership.28

The CIA Bulletin reported that “immediately after the news of President Kennedy’s death,” Castro ordered an island-wide “defensive military alert.” The analysts knew this from intercepted Cuban military and foreign diplomatic communications. By nightfall on November 22, Cuban army and navy units had been deployed to strategic positions around Havana and the north coast. According to one of the intercepts, Fidel was “frightened” that the United States might invade.29

When Castro’s first speech was broadcast, Oswald was still being interrogated in Dallas. What might he say that would make matters even worse for Cuba? What would the Mexican receptionist tell her government when she was interrogated? What else could emerge? The wiser choice for Fidel might have been to wait a while longer before speaking, but rambling orations were his lifelong addiction. And practical reasons compelled him to appear as well.

Until he spoke, Cuban officials and the state media had no idea what to say about the assassination. Kennedy had been the revolution’s most despised and feared enemy, regularly denounced and reviled. How should the dead president and his assassin be treated? A CIA analysis of the speech pointed up the dilemma: “how to react to a crime whose victim had consistently been a prime target of Havana’s vituperation.” Until Fidel’s appearance, the state-controlled media had refrained from commenting at all.30

The first reaction of some Cubans was to celebrate the president’s death. A JMWAVE source on the island reported spontaneous outbursts at workplaces and neighborhood defense committees. In Mexico City, DGI agent Luisa Calderon was heard rejoicing in a telephone conversation secretly recorded by the CIA’s station. When told the news by an unidentified female caller an hour after the assassination, she exclaimed “How great!” Then, mistakenly informed that “Kennedy’s brother and his wife were also injured,” Calderon laughed and again blurted “How great!” Kennedy, she said, was “a degenerate, unfortunate, an aggressor.” The caller told her the president had been shot three times in the face. Calderon thought that was “perfect.”31

Fidel was not aware of that conversation at the time, but he knew that he had to go public to establish clear policy and propaganda guidelines. The regime issued orders prohibiting “manifestations of pleasure.” On November 23, Fidel laid out entirely new parameters for a populace that had been taught to hate Kennedy. He spoke of the deceased president with uncharacteristic deference, referring to him repeatedly as “President Kennedy.” “We always cease our belligerency at death,” he declared, “we always bow with respect at death, even if it is an enemy.” That was not true: Fidel displayed no such forbearance after the deaths of other enemies, sometimes, as already mentioned, even those that occurred decades earlier.

In the ensuing nearly fifty years until this writing, Fidel never again spoke or wrote a disparaging word about Kennedy. Instead, he often praised the president, sometimes lavishly, sounding like the ebullient sword bearers of Camelot or another court biographer. He became obsessed with Kennedy’s memory, inviting a succession of family members to the island and graciously meeting with them. He hosted a particularly poignant dinner with John F. Kennedy Jr. in October 1997 in Havana. “We got together as friends,” Castro wrote.32

After the assassination, Fidel never openly connected either Kennedy brother with assassination plots against him. In fact, however, Cuban intelligence had tracked the three most serious ones from their initial stages. Castro knew he had been in the Kennedy administration’s crosshairs since before the Bay of Pigs and that he was the target in the fall of 1963 of the murder and coup conspiracy built around Rolando Cubela. Fidel was aware too that Attorney General Kennedy was the driving force behind the plot.

But once Kennedy was dead, Castro always put the blame for the conspiracies squarely on the CIA. His logic was impeccable—and transparent. Accusing the Kennedy brothers of involvement in conspiracies against him would antagonize Americans who idolized the fallen young president. And more critically, Fidel knew that doing so would arouse suspicions that he had been motivated to retaliate in kind.

There was a more urgent priority too when Castro spoke on November 23. He needed to disassociate himself completely from Oswald. If the grieving American public concluded that the assassin had somehow conspired with Cuba, Fidel knew the survival of his revolution would be at risk. So he was unequivocal about not having known anything about Kennedy’s assassin.33

The commander in chief spoke again about the assassination, at the University of Havana, on November 27. The CIA’s Cuba Daily Summary reported two days later that the speech “obviously was a carefully prepared refutation of charges of complicity between Castro’s regime and Oswald.” The analysts added that it “neither proves nor disproves that he had advance knowledge of the plot.”34

Adopting the position he and Cuban propagandists would push from that moment on, Castro declared categorically that Oswald was not the real culprit. Kennedy’s assassin was dead by then, murdered in Dallas police headquarters by small-time mobster Jack Ruby. According to Castro: “This demonstrates that the persons guilty of the death of Kennedy needed and urgently had to eliminate the accused at any cost.”35

Fidel repeated that he knew nothing of Oswald before the assassination. Referring specifically to the Mexico City consulate visits—visits that by then had been covered extensively by the media—he issued the second of his denials. Meaning himself and the government, he again employed the first-person plural pronoun “we,” as was his custom: “We did not know about it.”

And then he went farther out on that limb. “We have no other background for the accused . . . other than what has been published in the press.”

These and the earlier denial now constituted the official Cuban position. Government leaders and spokesmen would never waver from it. Laddie, however, knew better. He was in Havana when Castro delivered the two speeches and probably heard them live. His desire to expose Fidel’s lies to American intelligence may have been among his motives for defecting in the first place.36

He told Swenson that when news of the assassination reached the DGI, “it caused much comment concerning the fact that Oswald had been in the Cuban embassy.” He also heard Mexico Center chief Manuel Vega speak about Oswald’s visit. Vega had been reassigned from Mexico in October 1963, later returning for a second tour in mid-April the next year. After lunch one day soon after the assassination, Vega talked about it with Laddie and about ten of their colleagues at DGI headquarters.37

Laddie believed that Vega had seen Kennedy’s assassin at the consulate. And he thought that Rodríguez López, the deputy Center chief, had as well. “I feel sure,” Laddie told Swenson, that Vega would have requested permission from headquarters to issue a visa. It was standard procedure for DGI officers to screen visa applicants. When Laddie met with representatives of the House committee in 1978, he revealed additional details that had not come up in the debriefings with Swenson: The DGI routinely secretly photographed and recorded visa applicants in Mexico.38

Testifying before the House committee in 1978, Ray Rocca had the same impression. He thought Oswald’s arguments with the Cubans took place “in the very offices of the DGI, and that the DGI chief must have been in hearing range.”39

Alas, fourteen years later, unintentional confirmation came from an unlikely source. DGI officer Alfredo Mirabal, the incoming Center chief, admitted to the House committee that he had prepared a report on Oswald for his headquarters. Mirabal said Azcue, the consul who had confronted Oswald, gave him “information” about the visitor. No doubt Mirabal was given the documents, membership cards, and newspaper clippings Oswald had brought with him. Mirabal said that it was “for my report.” Apparently, he did not realize he was contradicting what his commander in chief had solemnly claimed years earlier.40

Clearly, then, DGI headquarters was informed about the strange young American who presented himself as an adoring friend of the revolution. Moreover, Mirabal’s report—probably drafted with Vega’s assistance—went directly to Piñeiro’s desk via a secure radio link. Laddie knew there was no headquarters desk officer responsible for Mexico, as he had been for El Salvador, so there were no intermediaries between the Center and Redbeard himself. Operations run out of Mexico, affecting as many as a dozen Latin American countries, were that important to Piñeiro and Fidel.41

Laddie told Swenson what many other defectors have also reported: Castro buried himself in the minutiae of intelligence operations. He and Interior Minister Ramiro Valdés personally selected most DGI officers dispatched to Latin America. Seemingly routine matters, Laddie said, would “normally . . . be taken up with Castro.” Oswald’s pleadings and outbursts at the consulate rose well above the ordinary. Mirabal’s report would surely have reached Fidel.42

LADDIE, IT TURNED OUT, was not the only unimpeachable American intelligence source who reported on Fidel’s knowledge of Oswald’s visit to the consulate. In late May 1964, a few weeks after Swenson debriefed Rodríguez Lahera, a deep-cover American spy working for the FBI met with Castro in Havana. Fidel told him that he had indeed been informed about Oswald’s visit.

“Our people in Mexico gave us the details in a full report of how he acted when he came to our embassy.” Oswald had not just berated the Cubans when they refused him a visa. He had not just stormed out slamming the consulate door behind him.

According to Fidel, he threatened Kennedy’s life.43

Castro never imagined he was confiding that spring day in one of the most remarkable American spies of the cold war. Jack Childs was, in fact, the junior partner with his brother Morris in espionage operations run for twenty-three years against the uppermost leadership of the Soviet Union and its communist allies. Beginning in the early 1950s, Morris, the more intellectual and sophisticated of the brothers, ingratiated himself with Khrushchev, his successors Leonid Brezhnev and Yuri Andropov, and other members of the Soviet Politburo. As protégés of those communist titans, the Childses developed trusting relationships with Fidel, Ho Chi Minh, and eastern European communist chiefs. With their wives as accomplices, the brothers’ family spy network was known as Operation SOLO.

Born in czarist Russia, Morris and Jack emigrated in 1911 as children with their family to Chicago where, in their twenties, they joined the American Communist Party. Morris rose quickly and was selected to study subversion and covert tradecraft at the Lenin School in Moscow. It was there he was recruited by Soviet intelligence. Then he served for years essentially as the “secretary of state” of the American party, respected and welcomed by leaders of ruling Communist parties. Morris traveled fifty-two times to Cuba, the Soviet Union, and its satellite nations, returning with valuable information he shared with his FBI handlers. He ran as the Communist Party’s candidate for the United States Senate from Illinois in 1938.

But it was the younger brother, Jack, who first became an American agent. He was cold-pitched by FBI officers on a New York City street in 1951. He smiled sardonically when approached, according to John Barron’s definitive study. “Where in the hell have you guys been all these years?” He was easily recruited. “I never really believed in any of that communist bullshit,” he told them. For his efforts, the Soviet leadership awarded Jack the Order of the Red Banner in 1975, one of its highest distinctions for dangerous duty. Not to be outdone, the United States posthumously honored him with the National Security medal in 1988.44

Jack was flamboyant, a risk taker, and it was probably because of their similar personalities that he and Fidel got along so well. He told his Bureau handlers: “I am basically a con man. If I had a choice between entering a house by walking through the front door or crawling through a back window, I’d go through the window because that’s more exciting.” Soviet leaders used Jack as a trusted intermediary with Castro. They contrived a dinner meeting in Moscow to introduce the men in May 1963 during Fidel’s first journey to the Soviet Union. It went so well that Jack was invited to meet with him again.

A year later, during another trip to Moscow, Jack planned his first journey to Cuba. Before leaving, he was briefed extensively by a Soviet party official. Don’t trust Raúl Roa, he was told. “When he became foreign minister we were almost sure he would go straight to the State Department.” The KGB was well informed: The CIA had indeed attempted to recruit Roa in October 1962, at the time of the missile crisis, but he rejected the overtures. Jack was advised to deal instead with two other Cuban officials, reliable pro-Soviet communists in Fidel’s inner circle. He was also given sage advice about dealing with Castro. By then, Kremlin leaders had learned the hard way.45

“Comrade Fidel is a very sensitive comrade. Our experience with him has been to talk to him most carefully . . . we have learned there are times not to speak to him, because he is a man of many moods. If his mood is good, he will listen, he will agree with you. But should it be bad, he would pout and shout.” Memories of Castro’s Armageddon letter were still vivid in the Kremlin. Jack later wrote that “they were depending on me to go there to talk sense to Castro.46

He left Moscow on May 18, 1964, on a direct Aeroflot flight to Havana. “When I first arrived, my request was to see Fidel first,” Jack recorded in a long letter to Gus Hall, the head of the American Communist Party. But as with even the most distinguished guests, he would be kept waiting. It was standard practice for Fidel; he manipulated visitors this way, keeping them on tenterhooks, not knowing if he would deign to meet with them at all. Often in the end, he arrived unannounced at midnight or later. “I didn’t dare leave the house for fear that I would miss Fidel,” Jack recorded.

Finally, “On the tenth night, several hours before my leaving, he came to see me. I was received very well, greeted very warmly.” Rene Vallejo, an American-trained doctor who was Fidel’s personal physician, interpreter, and aide, accompanied him. Jack wrote Hall: “My regards and greetings to Castro were very dramatic and effective. He liked them.” He gave Fidel an expensive fishing rod and equipment, gifts from Hall. They were getting along famously.47

Castro wanted to know how to establish better communications between Havana and the American party. He asked Jack what he and his communist associates knew about the Cuban exile community. “I told him we know very little . . . they are running around the streets gossiping and spreading false rumors.” Castro agreed, using his favorite term of derision: “they are nothing but a bunch of worms.”48

Then, seemingly out of the blue, Fidel asked Jack: “Do you think Oswald killed President Kennedy?”

Jack wrote: “Before I could answer, he said, ‘he could not have done it alone. I am sure of that. It was at least two or three men who did it, most likely three.’”

Castro explained that “soon after the president was assassinated,” he and a number of Cuban sharpshooters reenacted the scene. They used rifles similar to the Mannlicher-Carcano with telescopic sights and, according to Jack’s account, “shot at the target under the same conditions, same distance, same height.” Quoting Castro, Jack wrote that “after having aimed and set the sights and squeezed the trigger and the shot was fired, then the marksman must reset the telescopic sight again, reload the rifle again, by that time having lost many valuable seconds.” Fidel concluded that “it was impossible” for one man to have fired three times in such short succession.49

He had made similar points in his November 27 speech, boasting of his own expertise as a marksman who used telescopic sights. He organized the firing range exercise with obvious urgency within five days of Kennedy’s assassination and convinced himself that Oswald could not have rapidly fired three shots, two accurately, from the window of the Texas Book Depository. It was a self-fulfilling wish; he needed to rid himself of the Oswald albatross by whatever means. But the sharpshooter exercise bore no resemblance to what really happened the day of the shooting in Dallas.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover informed the Warren Commission that his firearms experts also conducted tests and “determined that three shots could be fired with the same kind of rifle and sight used by Oswald in the five to six seconds which were available.” That became the commission’s conclusion too and led to the controversial “single-bullet” judgment about the assassination. Later, author Gerald Posner interviewed an FBI firearms expert who confirmed that it “required no training at all to shoot a weapon with a telescopic sight.” Adjustments after each shot are not necessary. Fidel was wrong, or lying, but to this day he has not abandoned his position.50

He was not finished with his monologue with Jack. Castro went on to tell the American what Oswald shouted as he bolted from the Cuban consulate.

Presumably that had been included in the report cabled to Piñeiro by Mirabal and Vega. Fidel said that Oswald “[s]tormed into the embassy, demanded the visa and when it was refused to him headed out saying, ‘I’m going to kill Kennedy for this.’”51

Jack’s letter to Hall contains only that much information. John Barron’s book about Operation SOLO goes no further either. I have reviewed the Morris Childs and John Barron collections at the Hoover Archives at Stanford University but found no more details.

But recently I discovered a newly declassified FBI document at the National Archives. A Top Secret report from the FBI office in New York to Hoover on June 12, 1964, it included additional information provided by Jack. He said that Castro had been “in a very good mood” and was not under “the influence of liquor” when they met. Fidel had spoken “in broken English” and Hoover was told “there is no question as to the accuracy of what he said (because) the informant indicated that he had made notes at the time Castro was talking and he had scribbled down what he considered was important.”52 Seemingly unaware that Fidel had denied knowing anything about Oswald before the assassination, Jack reported that “Castro received the information about Oswald’s appearances at the Cuban embassy in Mexico in an oral report from ‘his people’ in the embassy, because he, Castro, was told about it immediately.” The FBI’s field report added that “Castro was neither engaging in dramatics nor oratory,” and reiterated that he “was speaking on the basis of facts given to him by his embassy personnel who dealt with Oswald, and apparently made a full, detailed report.”53

That Jack repeated the story accurately cannot reasonably be disputed. I. C. Smith, a retired senior FBI official involved in Operation SOLO, told me that Jack “was an extreme risk taker, but it did not detract from his reporting,” and that “no one in the FBI ever accused him of embellishing.” Although there has never been any doubt about the veracity of the Childs brothers’ reporting, Jack’s recollections of the meeting with Fidel have received scant attention in the nearly 50 years since. Yet they provide conclusive evidence that Fidel has been lying about Oswald since November 23, 1963.

On June 17, 1964, Hoover summarized Jack’s meeting with Castro in a Top Secret letter to the Warren Commission’s chief counsel. But he conveyed only the minimal essence of Jack’s story. The FBI director—who from the start of his investigation was wedded to the conclusion that Kennedy’s death did not result from a conspiracy—trivialized what Jack reported.

According to the letter, Fidel had merely repeated what he had said in public on November 27. But, in truth, that speech and what Jack heard were substantially different. Castro had said nothing publicly about Oswald’s threat or the firing range exercise. Hoover described Jack as “a confidential source who has provided reliable information,” not an American superspy who had been reporting valuable strategic insights for years. Jack’s report was made to sound like hearsay in Hoover’s telling, and he included none of the substantiating information the New York field office had provided him days earlier.

No wonder the commission paid no attention to his letter. Later two senior staffers said that they could not recall ever seeing it, and former CIA director McCone told a journalist in November 1976 that he had never seen it either. In essence, Hoover marginalized the best evidence that Castro was lying and hiding information of critical importance to the investigation. Had the FBI been more forthcoming, Fidel’s lies might have become apparent to assassination investigators and raised doubts about what else he was concealing.54

Author Jean Davison, whose 1983 book on Oswald was a major contribution to the Kennedy assassination literature, cited a corroborating source, a British journalist named Comer Clark. He claimed to have heard an account nearly identical to Jack’s from Castro in July 1967.

In this version, Fidel is quoted saying that when Oswald was at the consulate, he declared that “he wanted to work for us” and to “free Cuba from American imperialism.” And then, Fidel said, Oswald threatened to kill Kennedy. Some historians have discounted this reporter because he published his account in a sensationalist paper and wrote purple-tinged exposés for others. Davison concluded, nonetheless, that there are “several good reasons” for believing that the reports of the two sources were reliable. Not least was their near-perfect symmetry.55

Representatives of the House committee asked Fidel about the journalist’s account in April 1978 in Havana. That story was considerably easier to refute than the Operation SOLO report would have been, but the Childs brothers were still providing valuable information from inside the communist bloc and remained under the deepest cover. Hoover’s letter to the Warren Commission, not fully declassified until November 1993, could not be used. The congressional investigators had no choice but to rely solely on the shakier of the two reports.

Never at a loss for words, Fidel denied ever quoting Oswald or meeting with the British reporter. “I am absolutely certain that interview never took place. This is absurd. I didn’t say that. It’s a lie from head to toe.” There was no way to refute Fidel; by that time, the journalist had died.56

The meeting with House committee members and staff was conducted in Fidel’s offices in Havana, at his pleasure. The Americans were deferential. They did not follow up with tough questions or press him as they do in hearings in Washington with sitting-duck witnesses arrayed before them. Fidel sat with a claque of his DGI assassination experts who helped him with his responses. One of them appeared to be as well informed about Kennedy assassination trivia and lore as any American conspiracy buff. Since that meeting, no one has questioned Fidel again on the record about Oswald’s parting words at the consulate.

Azcue and Mirabal, the two Cubans who admitted dealing with Oswald, were also strident in their denials. Mirabal said the allegation was “totally absurd . . . incredible.” Referring to the United States, Azcue said, it is “ridiculous that we should attempt to walk into the mouth of the lion.” The faithful Mexican receptionist hewed to the official Cuban line too, claiming not to remember any threatening comments from Oswald.

But they should not be considered more credible than Jack Childs. Mirabal— known to his colleagues as “Eulogio”—was an experienced DGI officer. Laddie had plotted Cuban subversive operations in El Salvador with him when visiting the Mexico Center. Azcue was described in a CIA agent report in 1960 as “blindly antagonistic to the United States,” and his testimony was suspect for another reason. He insisted that the man he argued with at the consulate was not Oswald but a double, an imposter. And he expressed “absolute certainty” about it. Azcue was doing the regime’s bidding by propounding another of the canards its propagandists have repeated endlessly.57

J. EDGAR HOOVER HAD DONE his best to bring down the curtain on the assassination investigation. By June 1964 in his view, the Warren Commission’s production had to be brought to a close. Richard Helms, the “man who kept the secrets,” as his biographer Thomas Powers aptly described him, made sure the house lights were turned off.

It appears that within the CIA, Laddie’s belief that Fidel had lied about Oswald was deemed of no consequence. His reporting was filtered and minimized for the Warren Commission staff. The brazen, Kennedy-hating Luisa Calderon was also passed over lightly. The Warren Commission was told she was a DGI officer, but it was given no other information about her. She might have attracted more investigative interest had the commission been provided transcripts of her phone conversations. Some students of the assassination consider one, with an unidentified male caller about four hours after Kennedy died, as a smoking gun pointing straight at a Cuban conspiracy. The caller asked Calderon if she knew what had happened in Dallas.

“Yes, of course,” she replied. “I learned of it almost before Kennedy.”58

That could suggest she had foreknowledge of the assassination. House investigators later pursued the possibility vigorously, but to no end. Calderon was not made available to meet with the committee in Havana but denied any prior knowledge of Oswald in the written statement the Cuban government provided. Her strange remark, of course, can be interpreted in a variety of ways. Nonetheless, in its concluding report, the committee criticized CIA for withholding the transcripts from the Warren Commission.59

There was another exchange between Calderon during the same conversation that, surprisingly, has not drawn attention before. Speaking of Oswald, the unidentified person told Calderon:

“Oh yes, he knows Russian well, and also this fellow went with Fidel’s forces into the mountains, or wanted to go, something like that.”60

Calderon did not appear to be surprised, and the caller quickly changed the subject. The reference appeared, however, to recall Oswald’s Marine Corps service in southern California. It will be recalled that he allegedly met with Cuban diplomats—or, more likely, intelligence officers—in Los Angeles in 1959, when he first hoped to volunteer as a guerrilla fighter for Fidel. Calderon’s caller was probably also DGI and, by the time of the conversation, probably had reviewed Oswald’s records in Havana. But, this Calderon exchange also was not presented to the Warren Commission.

These and other omissions turned out to be the least of what Helms and CIA concealed. The commission was never told about the Kennedy-era assassination plots against Castro or the brutal secret war against Cuba waged out of JMWAVE. Worst of all, also kept under tight wraps was the ultra-secret plot with Rolando Cubela that coincided with Kennedy’s death.

How different the assassination investigation might have been if Helms had told the Warren Commission what he and Des and Bobby Kennedy knew better than anyone: that Castro had a compelling motive to conspire against John F. Kennedy’s life.

Lee Harvey Oswald had wanted since his Marine Corps days in the late 1950s to bear arms for Fidel and the Cuban revolution. Castro “was his hero . . . he would be happy to work for [his] causes,” recalled his wife Marina. Oswald posed as a militant in this photo Marina took in the backyard of their rented apartment in Dallas in 1963. He killed Dallas police officer J. D. Tippit with the pistol on his hip. The rifle is the one he used to assassinate President Kennedy.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives

The “Tourist” shortwave radio Oswald acquired in the Soviet Union was found in his rented room in Dallas after his arrest. He is believed to have regularly listened to incendiary Radio Havana broadcasts in English. Among others, he may well have heard coverage of Fidel’s tirade on October 30, 1963, condemning the CIA for plotting “subversion, espionage, and coups.”

Photo courtesy of the National Archives

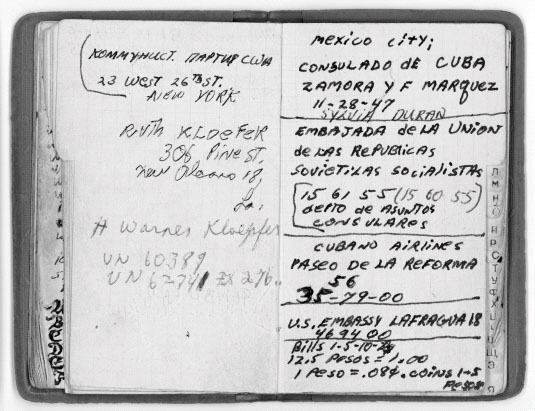

Oswald’s pocket-sized address book was also found among his belongings. These pages show that he kept the phone number of Silvia Duran, the receptionist at the Cuban consulate in Mexico City. If he called her number in the days just before the assassination, he may actually have spoken to Cuban intelligence officer Luisa Calderon, who has never been questioned about Oswald.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives

New Yorker Samuel Halpern joined CIA at its inception in 1947 after serving in Ceylon during his wartime OSS service. An indispensable aide to Bill Harvey, Richard Helms, and Des FitzGerald, he never hedged when testifying about the Cuba wars of the early 1960s. Asked under oath, “When you said get rid of [Castro], you meant kill him?” he answered, “Yes, sir.”

Photo courtesy of the Halpern Family

Harold “Hal” Swenson joined Bill Harvey's Task Force W in October 1962, about a year after this photo was taken. Later, as chief of Des FitzGerald’s counterintelligence staff he clashed with his boss. In 1976 he testified that he considered the Cubela plot “dangerous and stupid . . . a lot of nonsense.” There was good reason, he realized, “to doubt AMLASH’s reliability.”

Photo courtesy of Sally Swenson Cascio

Richard McGarrah Helms avoided the taint of the Bay of Pigs calamity of April 1961, but he was reluctantly inducted to manage the second and third phases of the covert campaigns against Cuba. He testified that “almost the entire energy” of the CIA clandestine service he headed from 1962 to 1965 was devoted to ousting Castro. “The Kennedy brothers” he said, “wanted to unseat Castro by whatever means.”

The Groza “Thunderstorm” miniature assassination pistol is double-barreled and silent when fired, small enough to be held in the palm of one hand. In September 1988 Fidel ordered his intelligence operatives to acquire one from the KGB to be used in the planned assassination of Florentino Aspillaga. Castro then personally managed that unsuccessful operation, directing most of its details.

Photo courtesy Maxim Popenker photo collection