Read on for a preview of Lives of the Poets

A stunning volume of epic breadth which connects the lives and works of over 300 English-language poets of the last 700 years.

Lives of the Poets traverses the landscapes of biography, form, cultural pressures and important historical moments to tell not just a history of English poetry, but the story of English as a language.

My main guides through the changing worlds of poetry in English are poets, particularly those who take an interest in their art and that of their fellow writers. Down the centuries poetry has been singularly blessed with articulate practitioners. They maintain a continuous conversation with one another, across languages and centuries. Poets live so long as their poems are heard, assimilated, handed on. The echo of Dante in Eliot or of Sappho in H. D. or Adrienne Rich is part of the larger continuity in which all of us who love the art have a right to participate as readers or writers. Among poet-critics of the twentieth century, Robert Graves, Randall Jarrell, C.H. Sisson, Donald Davie, Derek Walcott, Eavan Boland and John Ashbery were congenial companions, T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound exigent (if not always agreeable) masters. Earlier companions and masters include Sidney, Dryden, Dr. Johnson—who provided my title—Coleridge, Shelley, Poe…

Lives of the Poets traces the development of poetry in English from the fourteenth to the threshold of the twenty-first century, taking non-English poetry into account when its impact is registered. When the book was written it could not have gone any further in time without becoming prophetic, and prophesies are always erratic. It could have started earlier, however. Lives of the Poets was launched in Cambridge in 1999, where my elder son, reading Anglo Saxon at the time, asked me why I had omitted the Old English poets. Chastened, I later put together a series of critical anthologies entitled The Story of Poetry, rooted in this book, and added the Anglo Saxon poems into the first volume, with a substantial introduction. At the launch of that book my son, still at Cambridge, said, “I think you were right in the first place to leave out the Anglo Saxons.”

Would it make sense to start this history of English poetry as far back as 657, with Cædmon? The scholar and critic A.R. Waller thought so. “And from those days to our own,” he wrote a century ago, “in spite of periods of decadence, of apparent death, of great superficial change, the chief constituents of English literature—a reflective spirit, attachment to nature, a certain carelessness of ‘art’, love of home and country and an ever present consciousness that there are things worth more than death—these have, in the main, continued unaltered.” Changes may seem to us more than superficial, the thematic constants more complex than they appeared to Waller. Sixty years after him, his argument persisted. “Microcosm and macrocosm, ubi sunt, consolation, Trinitarianism—these are but some of the ideas and motifs,” wrote Stanley Greenfield, “that Old English literature shares with the works of later writers like Donne, Arnold, Tennyson, and Milton.” The English poets he calls to the witness stand undeniably deploy the “motifs” he lists, but those motifs, singly or in combination, are characteristic of any Germanic literature—indeed, of almost any literature we might care to name. Old English poetry was already remote in time and temperament from Chaucer and Gower, who are six centuries closer to it than we are. Its affinities with Langland and the work of the Gawain poet, and with the alliterative verse of Richard Rolle of Hampole and surviving shreds of popular verse are, apart from the alliterative tic, remote in tone and manner.

The spirit of the Old English may survive in the Border Ballads but the line cannot credibly be drawn much further forward. Gerard Manley Hopkins, Ezra Pound and W.H. Auden used the old resources in selective ways, looking for antidotes to the prosodic decorums of their periods. But to them Old English was a language as foreign as Welsh or Icelandic, a poetic rather than an immediately linguistic or lexical resource. Old England is another country, Old English a language as foreign as German or Dutch. If we started there we would need to start again a few centuries forward. We are all the Norman Conquest’s post-colonials. I leave out the Anglo Saxons once again.

* * *

The aspects of poets’ lives that matter in this context are those that gratuitously entertain us, for example the witch-crafted death of Robert Henryson, the libidinal vagaries of Robert Burns or the last medical consultations of Emily Dickinson; and those that clarify the development of their work and that of other writers. Inevitably, from the continuities between writers comes a sense of canon, though not a stable one. In each generation, some poets vanish, others re-emerge; only a few keep their heads continually above water even though, as in the case of Milton, fellow swimmers may do their damnedest to drown them for ever.

The colonial diaspora of English complicated and enriched things, bringing new energies and refreshing old. The early chapters of the book pursue a more or less linear chronology; later chapters make increasingly complex connections across times and continents. Injustice is done, and undone. The spurns that patient merit takes in its own age can be repaid tenfold in a later age, as in the cases of John Clare, Emily Dickinson, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Frank O’Hara and James K. Baxter. The poets themselves are the chief narrators and critics so that we get to know them well before we reach their home chapters. Modern theorists portray canons as repressive constructs, and they can be, they have been. Each age has its history of deliberate omissions. But so long as our sense of canon is open and unstable, seeking to include rather than omit, it is a generous principle that underscores our sense of poetry as an open continuum.

Of the four voices that speak in the first chapter, Derek Walcott and Les Murray remain defining presences. Seamus Heaney and Joseph Brodsky have died, and despite their legacy the sense of coherence imparted, at the end of last century, by this international poetic “superleague” (a journalistic term Blake Morrison coined for them, which helped rigidify a popular sense of where the Anglophone main stream ran) has weakened. “A time has come to speak unapologetically for a common language and to speak a common language of poetry. Almost.” My optimism fifteen years ago may still be prophetic, unless indeed the time that had seemed about to come has gone. The world of Anglophone poetry feels to me, as a publisher and editor with an international remit, more fragmented than it did in those bright days before the millennium turned, before 9/11 and the phosphorous and sodium dawns of the twenty-first century, with renewed nationalisms and bigotries, and a recrudescence of prescriptive aesthetics of various kinds keen to define, secure and exclude.

And the academy has continued to tighten its hold on every limb and organ of poetry: a majority of Anglophone published poets nowadays acquired their skills in writing schools and have in turn become teachers of poetry. The discourse (that very word, discourse, reeking of chalk dust) that surrounds poetry is often voiced in terms peculiar to the specialisms of the academy. Not that all critical and creative programs promote the same decorums: there is variety in the degree of emphasis each lays on aesthetic, political and commercial outcomes. And just occasionally in Britain a provocation elicits a unanimous response. On 1 June, 2014 spokesmen for the poetry constituencies were invited to be ruffled by the Guardian, and they obliged. The journalist Jeremy Paxman, clearly not feeling too fresh after chairing the judging panel for the Forward Poetry Prizes, having read 170 collections and 254 single poems, said: “I think poetry has really rather connived at its own irrelevance and that shouldn’t happen, because it’s the most delightful thing. […] It seems to me very often that poets now seem to be talking to other poets and that is not talking to people as a whole.”

Much of what he is reported as saying was intended to elicit the outrage that becomes news. Poets, he suggested, should be summoned before an inquisition of “ordinary readers” to explain themselves and justify their practice. Senior prize-winning professor poets from writing programmes rushed to the defenses. How frail those defenses have become. Professor Michael Symmons Roberts declared, “There is an awful lot of very powerful, lyrical, and readable poetry being written today,” and reassured Paxman that, “We are still a nation which feels it needs and reaches for poetry at key moments; what has been lost is the habit of buying and reading books of poetry,” that we turn to poetry, as we go to church, for consolation: funerals, weddings… and it survives on the radio. Contemporary poetry is not useful in these terms.

Professor Jeremy Noel-Tod cheerfully quoted Frank O’Hara, “If they don’t need poetry, bully for them. I like the movies too.” Still, there was a whiff of triumphalism: “Frank O’Hara was once patronised as a niche poet of the New York art scene. Fifty years later, he’s being recited by Don Draper on Mad Men and is one of the most influential voices around.” Not only radio: poetry makes it on to TV, too. Dr George Szirtes in the Guardian of 2 June went atavistic. “Poetry is as ancient as language itself, and the sense of the poetic precedes language. Animals could be charmed by music; mere drumming can heal the sick.” Language, which some believe is a crucial ingredient of poetry, hardly figures in his primeval argument. “The poetic even penetrates to football commentators who exclaim ‘Sheer poetry!’ at a particularly wonderful moment. They tend not to exclaim ‘Sheer prose!’ We feel poetry rather than understand it. We know it’s there because it gets under the skin of the conscious mind.” Not a felicitous metaphor, we might think. And this was as good as the argument got.

Poems can themselves reveal even more about poetry’s history than a poets’ prose. Nothing illuminates Chaucer’s so clearly as the poetry of Spenser, or Spenser’s as that of Milton and early Blake, or Milton’s as that of Wordsworth. Whitman lives, changed, in Pound and Lawrence, Herbert in Coleridge and Dickinson, Byron in Auden and Fenton. Each achieved poem is a gathered energy that transmits itself, undiminished, to attentive receivers. Its energy is generated by its occasion, which may be love or thanks, lament, rage, celebration, observation, or simply an engaging semantic accident or a rhythm; but it is also charged by poems that hover around it as echo, memory or example. Parody, homage, theft, adaptation: the generous energies are diminished only by ignorance. This is the singing school that mattered in the time before creative writing programs, its doors always ajar, its blackboards written and over-written, the books on desks and window ledges full of bright markers, marginalia, bus-tickets, gum-wrappers, love letters and pressed heather. It is the school that matters now, a free school requiring intelligence and imagination.

JOSEPH BRODSKY, DEREK WALCOTT, SEAMUS HEANEY, LES MURRAY

While the Irish football team played the Soviet Union in 1988, four English poets were confined in a radio studio in Dublin—it was the Writers’ Conference—to take part in a round-table discussion. English-language poets, that is, for none of them accepts the sobriquet “English” and one has vehemently rejected it. In the chair was an anglophone Mexican publisher, me.

First of the four was Russian. Joseph Brodsky, a Nobel Prize winner, was attempting that almost possible Conradian, Nabokovian transition from one language to another, writing his new poems directly in English. Jet-lagged and impatient to return to the soccer, he expressed strong opinions on politics, religion, poetry and sport. In his essays he has argued that, as imperial centers corrode and weaken, poetry survives most vigorously in remote provinces, far from their decaying capitals. One thinks of Rome. Now that the British and American claims to the English language have loosened, the art of English poetry continues to thrive. The bourse may still be in the publishing centers of London or New York, but the shares quoted there are in poetic corporations with headquarters in New South Wales, St. Lucia, County Wicklow...

There is a triumphalism in this line of argument: emancipation. The postcolonial is as much a fashion in literature as the Colonial is in home decoration. Brodsky might have conceded (he did not) that ethnicity, gender and sexual preference can themselves be provinces or peripheries in which, even at the heart of the old geographical centers of empire, poetry can grow. It is an art that thrives when language itself is interrogated, from the moment John Gower challenged himself, “Why not write in English?” to Wordsworth’s asking, “Why not write a language closer to speech?” to Adrienne Rich’s asking, “Why write in the forms that a tradition hostile to me and my kind prescribes?” History and politics can play a part: they propose questions. In poetry the answers come not as argument but as form.

Over a century and a half ago America began to establish its independence, kicking (as Edgar Allan Poe put it) the British grandmama downstairs. Early in this century Scotland began to reaffirm its space, and Ireland too, a space that is firstly political and then cultural. We can speak of sharing a common language only when we possess it, when it is our language rather than theirs. For the Jamaican poet and historian Edward Kamau Braithwaite the English of the educational system in which he was raised, the English of the poetic tradition, is theirs. For many black writers in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s, it was theirs. For working-class English writers such as Tony Harrison it was theirs. When writers interrogate language, they set themselves one of two tasks: to reinvent it, or to take it by storm and (as the novelist Gabriel García Márquez puts it) “expropriate it,” give it to the people, often for the first time. “I hate relegation of any sort,” says Les Murray. “I hate people being left out. Of course, that I suppose has been the main drama of my life—coming from the left-out people into the accepted people and being worried about the relegated who are still relegated. I don’t want there to be any pockets of relegation left.”

A time has almost come—the round-table discussion was early evidence of it—to speak unapologetically of a common language, at least for poetry. Instead of affirming separation and difference, we can begin to affirm continuity—not only geographical but historical, analogies and real connections between Eavan Boland and Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Allen Ginsberg and William Blake, John Ashbery and Thomas Lovell Beddoes, Thom Gunn and Ben Jonson, Elizabeth Bishop and Alexander Pope. The story that includes all poets can be told from the beginning.

The second poet in the studio that afternoon was Derek Walcott, born in Castries, St. Lucia, in 1930, of a West Indian mother and an English father.

I’m just a red nigger who love the sea,

I had a sound colonial education,

I have Dutch, nigger, and English in me,

and either I’m nobody, or I’m a nation.

His was a francophone and Roman Catholic island; he is from an English-speaking Methodist culture. “Solidarity” is not the issue for him that it has become for Brathwaite. He distinguishes between English, his mother tongue, and the form he used at home, his mother’s tongue. He might have courted approval had he chosen to affirm himself in terms of race, but he chose instead to identify himself with all the resources of his language. After all, English wasn’t his “second language.” “It was my language. I never felt it belonged to anybody else, I never felt that I was really borrowing it.” In a poem about the shrinking back of empire, he writes, “It’s good that everything’s gone except their language, which is everything.” “They” have left it and now it is his. Shakespeare, Herrick, Herbert and Larkin belong to him just as they would to an English person. There’s no point in denying the violence and dislocations of colonialism, but if, given what history has already done, a writer responds by rejecting the untainted together with the tainted resources...

The third poet at the table was Seamus Heaney. Born in the north of Ireland, he has complained of being “force-fed” with “the literary language, the civilized utterance from the classic canon of English poetry.” At school, poetry class “did not delight us by reflecting our experience; it did not re-echo our own speech in formal and surprising arrangements. Poetry lessons, in fact, were rather like catechism lessons.”

He has tempered his views since he wrote of the “exclusive civilities” of English. At the round table he declared that the colonial and post-colonial argument is “a theme; it’s a way of discoursing about other things, to talk about the language. It’s a way of talking about being Protestants and Catholics without using bigoted, sectarian terms, it’s a way of talking about heritage. But the fact of the matter is that linguistically one is very adept.” He remembers as a child with “the South Derry intonation at the back of my throat” being able to hear, as he read, even though he could not speak it, the alien and beguiling intonations of P. G. Wodehouse. Language can be a medium of servitude; but it can also—properly apprehended—become a measure of freedom. “A great writer within any culture changes everything. Because the thing is different afterwards and people comprehend themselves differently. If you take Ireland before James Joyce and Ireland fifty years afterwards, the reality of being part of the collective life is enhanced and changed.”

The fourth poet, the Australian Les Murray, is a witness to the abundance of the English language and to the freedoms it offers. Born in 1938 in Nabiac, rural New South Wales, he was an only child and grew up on his father’s dairy farm in Bunyah. His mother died when he was a boy. In solitude he developed a close affinity with the natural world. Australia is a predominantly urban society; Murray is thoroughly rural. In 1986 he returned to Bunyah to farm, to live with the poetry of gossip, what he calls “bush balladry,” and to work for “wholespeak.” He takes his bearings, emblematically, from Homer and Hesiod: the arts of war and of peace (Hesiod’s Works and Days embodies the principles of permanence, while the Odyssey with its endless wandering and a world subject to strange metamorphoses, and the Iliad with its sense of social impermanence and conflict, illuminate the principles of change).

A voice exists for every living creature, human or beast. It is one of the poet’s tasks to listen and transcribe: the voice (the diction, syntax and cadence) of the cow and pig, the mollusk, the echidna, the strangler fig, the lyre bird and goose, the tick, the possum, “The Fellow Human.” The past is included in the present, and the fuller its inclusion, the less likely relegation will be. Murray works toward an accessible poetry, telling stories, attempting secular and (he is a Roman Catholic) holy communion. An anti-modernist, he might respond to Ezra Pound’s commandment “Make it new”: “No, make it present.”

Four writers in English with different accents and dialects, detained in a small recording studio in Dublin, deprived of the big match, all more or less agreeing on the integrity of their art, its place in the world, and on the continuities that it performs. Released at last (the match, alas, was over), the poets returned to Dun Laoghaire for dinner. Their conversation was raucous: a competition of salty tales and limericks (“There was a young fellow called Dave / Who kept a dead whore in a cave”). Neighbouring tables tutted and simmered, and a literary critic from Belfast in her indignation reported the poets’ boisterous manners back to the Times Literary Supplement.

A time has come to speak unapologetically for a common language and to speak a common language of poetry. Almost.

“We all know where we are not at. We all know who our sublime superiors are,” says Derek Walcott. I had better declare a material interest in this common language of poetry and give a health warning.

When I was nineteen my father told me to pursue law or some useful vocation, anything I liked, he said liberally, even the Church or the army. What about publishing? Certainly not: speculation, gambling with uncertain futures or merely repackaging the past. When I became a publisher he advised me again: I was not to publish poetry. He echoed the Mr. Nixon of Ezra Pound’s “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley”: “And give up verse, my boy, / There’s nothing in it.”

I became a poetry publisher. Mr. Nixon was right—and wrong. The nothing can be very nearly the everything. But my father disowned me. We still exchanged letters, but he no longer took an interest in my future. I had none. I’d made myself a prodigal. I had also made myself free to adopt my own antecedents. I went in quest of them, and they were not easy to find. They survived—if at all—mostly in footnotes, obscure monographs and technical books.

The earliest were called scribes; they later became known as scriveners, printers, booksellers, and finally publishers. They worked in Southwark, then at St. Paul’s, in Paternoster Row, Bloomsbury, the Corn Exchange, St. Martin’s Lane, Vauxhall Bridge Road. Now we’re scattered, like poets, to the round earth’s imagined corners: Sydney, New York, Toronto, Jo’burg, Delhi, Wellington. Those who specialize are poor and have been poor for centuries. Why? So that poets—a few of them—can prosper. Publishers get written out of the story and poets live forever. Servants of the servants of the Muse, from the days of scriptoria to the world of desktop publishing, we are dogsbodies of the art: we edit, correct, scribe, typeset or key, print, bind, tout. Are we remembered?

How many of us can you name? William Caxton? Good. Maybe Wynkyn de Worde, just about. And after that—ever heard of Tottel, Taylor, Murray? You might recognize a name, but only because of Wyatt or Clare or Byron. On the whole, as far as readers are concerned publishers are the aboriginal Anon. Gossip about us is sparse and generally unpleasant. If we misjudge a writer or commit a small human or financial irregularity that touches his or her biography, then we come alive, villains of the piece, alongside unfaithful spouses and wicked stepparents.

We were the first readers of almost every poem that traveled beyond the charmed circle of a writer’s intimates. We said what would go in and in what order, we said change this, drop that (or we silently changed and dropped), we abridged and expanded. We assembled anthologies. We decided when a writer should go public, how long a book should live, how widely it should circulate. We commissioned, gambled, lost and sometimes won. Our childhoods, our money worries, our sexual arrangements, our one-night stands with a promising manuscript and our long nights by taper or sixty-watt bulb getting it right for poets, so that they might shine like stars in the perpetual nighttime of your attention, count for very little in the histories.

How a poem arrives at a reader has an effect on how it is conceived and written. The ballad sheet, the illuminated manuscript, the slim volume, the epic poem, the “representative anthology,” the electronic poem or performance piece—each makes different demands on the poet and has a distinct technology and market. Poets of the fourteenth century, dreaming of their work passing from hand to hand, have a different sense of their destiny from poets hammering away at word processors or rapping under strobes. Technology is a part of imagination. Parchment elicits one attitude from a writer, paper another. The very textures (not to mention prices) are part of the equation. The cost of eloquence. A quill, a biro and a keyboard download a poet in different ways, at different speeds. Without succumbing to “historical materialism,” we can register those differences. The gynecologist William Carlos Williams with quill on parchment would not have responded to the plums in the refrigerator as he did, or written all those little and big poems between patients, swiveling round from his consultancy desk to a typewriter impatient for his attention; and Shakespeare with a word processor might have left better texts and at least have run a spell check. Creative technologies evolve (not always for the better). So does language. So does publishing.

We publishers moved from open-plan scriptoria to stalls in provincial market towns to little bookshops and printers, to small shared offices, to private offices and back to open plan again. So many centuries! We began with Latin. The English we eventually scribed and later printed doesn’t immediately strike a modern reader as English. Only when translated into sound, spoken aloud, does it become comprehensible. If not, our job is to facilitate, to modernize.

And we have a life outside the office, beyond the marketplace. We sit up evenings by a hissing gas fire or under a dozen rugs and read hungrily. Among parchments or manuscripts, or unreeling a document on our screens, we are alchemists looking for gold. By messenger or post or down the line, or over an expensive lunch where we smile and pay, we’re receivers of work that’s often conceived in sunlight, in repose, in the country, in the jungle, in love’s raptures or the rich madness of betrayal, by women and men who live full lives. As for living, our authors will do that for us.

We make choices and reputations, and we are humble. Does a priest feel humble when he hears confession? Does a doctor show humility before a pregnant belly, a head cold or a boil? We have power, yet our authors make us invisible! We legitimize them, then bow to that legitimacy. Just occasionally we emerge from behind the arras, pierced like Polonius by a hundred bodkins shoved into us by poets, biographers and critics. Do we answer back? Can we at least tell a different story?

“Only a poet of experience,” Robert Graves says, “can hope to put himself in the shoes of his predecessors, or contemporaries, and judge their poems by recreating technical and emotional dilemmas which they faced while at work on them.” A publisher can, too. We turn many a falsehood into truth. Our mishearing or misreading has improved texts. Graves recommends copying out texts by hand, to discover where the weaknesses and strengths are located. “Analeptic mimesis” he calls it. It’s grand to have a Greek name for it. Second best is reading aloud: these are still the most efficient approaches to a poem.

I’m not a poet. What am I doing, what can I know, I who am worse—my father would have said—than a gambler? “You make books. But you know little. Just as the honey-bottler knows nothing about bees. Why should you be my Virgil, my guide, among the living and the dead?” Because I can read, I can speak, I have ears. I have memory. “But you’re entering protected territory. You’re no linguist, no prosodist, you’re not a historian or a philosopher. Specialists will have your guts for garters. What hope have you of escaping unscathed?”

No hope at all. But we’re all readers. Being a reader is a worthwhile liberty. I don’t doubt I’ll make errors—of emphasis, fact, commission, omission. But on the whole we’re the lucky ones. Specialists read from a specialism, finding a way through to what they know they’ll find. Say they’re philologists, literary historians or theorists. They have an agenda, poems slot into it. If we stumble across poems they’ve pinned like butterflies to an argument and try to unpin them so they can fly again, or die, they dismiss us as unlicensed. I prefer to be unlicensed, to read a poem, not a text. Poems, no matter how “difficult” the language when it first sneaks up on us, no matter how opaque the allusions or complex the imagery, no matter what privileges the author enjoyed or how remote his or her learning is from ours—poems because they’re there, because they’ve been published and survived, are democratic spaces. Poetry is language with a shape. It communicates by giving. It doesn’t conform to a critical code. It elicits answering energies from our imaginations—if we listen closely.

We should cultivate techniques of ignorance, C. H. Sisson says, in order to find out what’s there, not what we expected to find. Ignorance, if we acknowledge it, is a useful instrument of self-effacement, a way of eluding prejudice, reflex, habitual response. As soon as we’re properly ignorant we begin to develop a first rather than a second nature, to question even familiar things in ways that would not have occurred to us before, to hear sounds in poems that eluded our “trained” ears.

A particularly acid but astute biographer (Lytton Strachey) declared: “Ignorance is the first requisite of the historian—ignorance, which simplifies and clarifies, which selects and omits, with a placid perfection unattainable by the highest art.” The task is less to explain than to illuminate. We follow a rough chronology because it is convenient to do so, not because we are historicists; and beams of light from the twentieth century shine into the souks and chapels of the fourteenth; the seventeenth century is not extinguished in the twentieth but provides penetrating rays. As we approach a period or a poet in this story, we may feel anticipation as at reaching a familiar town—and surprise that it is not mapped quite as we expected.

Mercator in 1569 published his famous map projection, a vision of the world as the segmented peel of an orange. It took him a long time to get it right; it has been subject to adjustment ever since. How to reduce a lumpy sphere to a plane? Was he the first Cubist? At least his plane is a comprehensible, if not immediately recognizable, image of a sphere at a particular time. The task of drawing a world map of English poetry is like playing three-dimensional chess: you have the growing spaces that English occupies, and three quarters of a millennium during which the poetry has been written in a language gathering into standard forms and then, like Latin at the end of its great age, beginning to diversify into dialects that will become languages in turn. Any account of poetry in English will falsify.

I’m talking myself back to humility, not a virtue with which to embark on an adventure such as this. The best reader needs the seven deadly sins in double measure. Pride makes us equal with specialists and professional critics and impervious to their attacks. Lechery puts us in tune with the varied passions and loves that we encounter. We feel envy when a reader who has gone before preempts our response; this only spurs us on to fresh readings. Anger overwhelms us when injustices occur, and it should be disproportionate: when a poet dies in destitution or is lost for a generation or a century. We experience covetousness when we encounter poets we are prepared to love but their books are unavailable in the shops, so we covet our friends’ libraries or the great private collections. Gluttony means we will not be satisfied even by a full helping of Spenser or the whole mess of The Excursion; we feed and feed and still ask for more. Finally dear old sloth has us curled up on a sofa or swinging in a hammock with our books piled around, avoiding the day job and the lover’s complaint. These are necessary vices. The list is found in Langland, Chaucer, Spenser, Marlowe. They knew these vices from the inside, personified and warned against them; don’t imagine they were innocent. The lavish attention they gave to the vices reveals how much commerce they had with them.

Theorem number one: Wars and revolutions always come at the wrong time for poetry; the big possibilities of Gower, Chaucer and Langland, postponed by history and the rise of classical humanism; the lessons of Ben Jonson and the Metaphysicals, dispatched at the Commonwealth; then the appalling ascendancy of French and classical prejudices which eventually drove real talent to madness or the cul-de-sacs of satire and sententiousness; then the French Revolution with its seductions and betrayals wasting another generation of new things, turning it back, as it were, toward the prison houses of the eighteenth century. Theorem number two: The French have a lot to answer for, from Norman times onward; and the First World War, its bloody harvest of so much that was new and promised well, impoverishing modernism because it killed Hulme, Rosenberg, Brzeska and also Edward Thomas. There’s no straight line, it’s all zigzags, like history. Poems swim free of their age and live in ours; but if we understand them on their own terms rather than conform them to ours, they take on a fuller life, and so do we.

One could abandon writing

for the slow-burning signals

of the great, to be, instead

their ideal reader, ruminative,

voracious, making the love of masterpieces

superior to attempting

to repeat or outdo them,

and be the greatest reader in the world.

—Derek Walcott, “Volcano”

Poems swim free of their age, but it’s hard to think of a single poem that swims entirely free of its medium, not just language but language used in the particular ways that are poetry. Even the most parthenogenetic-seeming poem has a pedigree. The poet may not know precisely a line’s or a stanza’s parents; indeed, may not be interested in finding out. Yet as readers of poetry we can come to know more about a poem than the poet does and know it more fully. To know more does not imply that we read Freud into an innocent cucumber, or Marx into a poem about daffodils, but that we read with our ears and hear Chaucer transmuted through Spenser, Sidney through Herbert, Milton through Wordsworth, Skelton through Graves, Housman through Larkin, Sappho through H.D. or Adrienne Rich.

Reflecting on poets outstanding today: each has an individual culture. Ted Hughes dwells on Shakespeare, Thom Gunn on the sixteenth century, Donald Davie on the eighteenth. Poets are made of poems and other literary works from a past that especially engages them and of works by near antecedents and contemporaries that embed themselves in whole or in part in their imaginations. Some works stick as phrases, others as misremembered lines. There are also phrases and lines held deliberately hostage, jotted in a notebook for eventual exploitation. Reading T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, we can discriminate between fragmentary allusions that imagining memory provides and those that come from the hostage list. Other poems are less candid in revealing source and resource. Edward Thomas writes, “All the clouds like sheep / On the mountains of sleep”—an amazing image; its source is a poem by Walter de la Mare, and de la Mare’s source is Keats. Thomas’s genius is in choosing the image and adjusting it to his poem’s purposes, not in disguising its theft. There is no theft in poetry except straightforward plagiarism. Every poet has a hand in another poet’s pocket, lifting out small change and sometimes a folded bill. It’s borrowing, a borrowing that is paid back by a poem.

A poet is a kind of anthologist. Figuratively speaking, John Gower and Geoffrey Chaucer lined up the French poems and classical stories they were going to translate or transpose into English; they marked passages to expand or excise. From secondary sources (in memory, or on parchment) they culled images, passages, facts, to slot into their new context. Then began the process of making those resources reconfigure for their poem. Then they began to add something of their own. The scholarly sport of searching out sources and analogues is useful in determining not only what is original in conception, but what is original in mutation or metamorphosis, how the poet alters emphases, changes the color of the lover’s hair, adjusts motive, enhances evocations, to make a new poem live. Thomas Gray a few centuries later was making poems out of bits and pieces of classics, the Lego set from which he builds “Elegy in a Country Churchyard,” the most popular poem in English, read, for the most part, in blissful ignorance of its resources. “Blissful ignorance” is from Gray as well: “Where ignorance is bliss / ’Tis folly to be wise.” Phrases of verse that enter the common language are transmuted in the naïve poetry of speech. Individual speech itself is an anthology of phrases and tags—from hymns, songs, advertisements, poems, political orations, fairy tales and nursery rhymes—the panoply of formal language that form makes liminally memorable. As speakers, each of us is an inadvertent anthologist.

A poet is an inadvertent anthologist working at a different intensity. There is a tingling in the nerves. A poem starts to happen. Selection of language begins in the darkroom of the imagination, the critical intelligence locked out, coming into play only after a print is lifted out of the tray and hung on the wire to dry, the light switched on revealing what is there. The critical intelligence discards blurred, dark or overexposed prints at this stage. Those that survive become subject to adjustment and refinement, unless the poet is one of those who insist on the sacredness of the first take. Preprocessing has occurred: the Polaroid principle.

The greatest reader in the world has a primary task: to set a poem free. In order to do so the reader must hear it fully. If in a twentieth-century poem about social and psychological disruption a sudden line of eighteenth-century construction irrupts, the reader who is not alert to the irony in diction and cadence is not alert to the poem. A texture of tones and ironies, or a texture of voices such as we get in John Ashbery, or elegiac strategies in Philip Larkin, or Eastern forms in Elizabeth Daryush and Judith Wright, or prose transpositions in Marianne Moore and (differently) in Patricia Beer: anyone aspiring to be the greatest reader in the world needs to hear in a poem read aloud or on the page what it is made from. As a poet develops, the textures change. Developments and changes are the life of the poet, more than the factual biography. But the “higher gossip” of biography generally distracts readers from engaging the more fascinating story of poetic growth.

A poet grows, poetry grows. The growth of poetry is the story of poems, where they come from and how they change. It begins in the story of language. Where does the English poetic medium begin, what makes it cohere, what impels it forward, what obstacles block its path? The medium becomes an increasingly varied resource; the history of poetry within it is not linear, the rise and fall of great dynasties, the decisive changes of political history; in the eighteenth century it is possible for a Romantic sensibility to exist, for a poet to write medieval poetry, just as in the reign of Charles I poets might still write out of the Elizabethan sensibility, in Elizabethan forms. In the twentieth century the poetry of Pound and Eliot, of Masefield and Hardy and Kipling, of Graves, of the imperialist poets, of Charlotte Mew and Anna Wickham, all occupy the same decades, each anachronistic in terms of the others. William Carlos Williams begins in the shadow of Keats and Shelley and ends casting his own shadows; J. H. Prynne begins in the caustic styles of the Movement and the 1950s and develops his own divergent caustic strategies. There is a history of poetry and, within the work of each poet, a history of poems.

We have to start with language. And to start with language we must also start with politics. The struggle of English against Latin and French is the resistance; the struggle of English against Gaelic, Welsh, Irish and Cornish is a less heroic chapter. Imperial English generates new resistances. At every point there are poems, voice-prints from which we can infer a mouth, a face, a body and a world. A world that we can enter by listening as we move our lips through the series of shapes and sounds the letters on the page demand.

RICHARD ROLLE OF HAMPOLE, ROBERT MANNING OF BRUNNE, JOHN BARBOUR

Where do we first experience formal language? In lullaby, nursery rhyme, street rhymes, popular songs, anthems. In church, synagogue, mosque or temple, in hymn and scripture and sermon; in graveyards, on tombstones.

English poets at the start of the fourteenth century were sung to by their mothers or—orphaned by the plague—by foster mothers or relations. They were dragged to church, through churchyards full of individual and mass graves, many inscribed with scripture, others with Latin verses; inside they heard Latin intoned, and sang English, French and Latin. There were sermons in English, the priest pointed to bright paintings of religious events on the walls, or in the stained glass windows, or at statues and images—aids to make visible the truths of faith. Those images expressed a long tradition of symbolism and composition to feed the imagination. Incense clouded from the censers, spreading over upturned faces. The bright images hovered, as if removed, in another, an ideal and lavishly illuminated, sphere, above the reeking congregation.

In such polyglot churches, where shreds of paganism survived in elaborate ceremonial, the children who were to be poets learned that things could be said in quite different languages, and that the language they spoke at home or in the lanes always came last. They learned that there were parallel worlds, the stable Latin world of the paintings, windows, statues, and the world in which they lived, where plagues and huge winds and wars erased the deeds of men. Obviously the earth was a place of trial, hardship and preparation. They wrote out of this knowledge. Knowledge, not belief. Belief came later, when knowledge began to learn its limitation. Belief is an act of spiritual will, born of the possibility of disbelief, born with the spirit of the Reformation. That spirit was just beginning to stir.

Our starting point is fourteenth-century England, a “colonial” culture subject to Norman rules if not rule, with a Catholic spiritual government answerable to Rome. The people accept the ephemerality of this world and an absolute promise of redemption for those who practice the faith. They know that the language of learning is Latin, that the language of power and business Norman French, and that their English is a poor cousin. When the Normans took England they saw no merit in the tongue: an aberration to be erased, just as the English later tried to erase Irish and Welsh, Scots Gaelic and Cornish, or to impose English in the colonies. They succeeded rather better than the Normans did.

By the end of the fourteenth century, the time for English had come, with the poetry of Sir John Gower, Geoffrey Chaucer, William Langland, the Gawain poet and the balladeers with the dew still fresh upon it, with an oral tradition alive in market towns, provincial courts and manor houses. It took most of the century for this to happen, and by the end some high poetic peaks rose out of a previously almost entirely flat landscape.

The turbulent middle of the fourteenth century broke the prejudice in which English was held; it began to flex its muscles. Calamity was its patron. The Black Death first reached English shores before John Gower turned twenty, in the twenty-first year of Edward III’s reign. In August of 1348 it arrived from France at Weymouth. It devastated Bristol, and in the early part of 1349 overtook London and East Anglia. It was still at large in Scotland and Ireland in 1350. Consider what it was like, to learn each day of dead or dying friends, to see bodies carted through the streets or heaped in a tangled mess at corners. It was an especially disgusting illness that started with hard lumps and tumors, then scalding fever, gray patches on the skin like leprosy. Then the cough, blood welling from the lungs. A victim had three days: terror, agony, death.

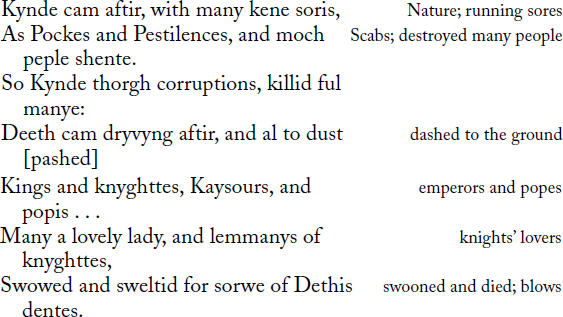

Langland describes it in a passage that the eighteenth-century critic Thomas Warton says John Milton may have stored away in his mind (in Paradise Lost, Book II, lines 475ff). Langland says:

All at once there were not enough peasants to work the soil, servants to tend the house, or priests to administer unction and conduct funeral services. No one was immune. Three archbishops of Canterbury and in Norwich eight hundred diocese priests, and half the monks in Westminster, all died in one year. Eight hundred priests. The Church was big; the Black Death was bigger. Women toiled in the fields, harvests were left to rust. Parliament was suspended, courts of law were not convened. It was a time of too much loss for sorrow, too much fear for civil strife. There were more dead than graves to put them in: they were piled in plague pits and covered with lime. If the plague made feast of the poor, it was at least democratic. The powerful were not immune: the king’s own daughter perished.

Another victim was a big-hearted anchorite who wrote verse, Richard Rolle of Hampole. “Full dear me think He has me bought with bloody hands and feet.” He was a man of soul. A poet-martyr. Perhaps he translated the Psalms. It is hard to establish authentic “texts” by an author unless a number of similar manuscripts survive. Most medieval writers formed schools, their works were copied, added to and altered. Much has been assigned to Richard Rolle that may not belong to him. Why was he such a bad poet, with only some occasional astonishing lines?

He was born about 1300 at Thornton-le-Dale near Pickering, North Yorkshire. The north of England was the center of English writing—furthest from Norman influence—but it began to lose out to the Midlands. Oxford was becoming focal, especially after the foundation of Balliol College around 1263. Rolle went to Oxford at a time when the friars still led exemplary lives. He learned Latin, disliked ordinary philosophical writers and loved scripture above all else. At nineteen he returned home, anxious about his soul, intending to become a hermit. He preached. The Dalton family set him up as a hermit on their estate. (Hermits were not unusual in the medieval world; they were licensed and controlled by bishops.) He never became a priest but may have been in minor orders. His authority was spiritual. After some years he moved to a new cell close to a hermit called Margaret Kirby; then to Hampole, near Doncaster. Cistercian nuns looked after him. On Michaelmas Day 1349 the Black Death took him. The nuns petitioned for him to be made a saint.

His verses—if they are his—express personal feeling simply. He began in the old alliterative tradition but progressed to rhyme. His followers imitated what was an easy style. What is his, what did he borrow or translate, and what belongs to his follower William Nassyngton? When we think we’re admiring Rolle we may be admiring Nassyngton’s imitation; but then there is not much to admire in Rolle or his followers. Already poets—even holy poets—are practicing techniques of false attribution: getting their work read by borrowing the authority of a revered name. Publishers began to practice this subterfuge two hundred years later, but it’s as well to remember that they learned that deception, and others, from religious poets.

Rolle especially loved the Psalms: “grete haboundance of gastly [ghostly, i.e., spiritual] comfort and joy in God comes in the hertes of thaim at says or synges devotly the psalmes in lovynge of Jesus Crist.” He wrote a Latin commentary; then another followed by English versions. It is hard to extrapolate a system of belief from his work, but his doctrine of love is not like other mystics’: he is alive to the world he only half inhabits. The good works a man does in this world praise God. Injustice offends caritas, and such acts particularly rile God.

His Latin works display, a friendly critic says, “more erudition than eloquence.” The surviving verse in English includes a paraphrase of the Book of Job, a Lord’s Prayer, seven penitential psalms, and the almost unreadable The Pricke of Conscience. It must have been readable once, for it has been widely preserved in manuscript. Warton copied it out and said: “I prophesy that I am its last transcriber.” In seven parts, it treats of man’s nature, of the world, death, purgatory, Judgment Day, hell’s torments and heaven’s joys. The verse is awkward to scan: a basic iambic tetrameter measure with six, seven and sometimes (depending on the voicing of the final e and how regular you want the iamb to be) ten syllables to the line, and from three to five stresses. It raises the crucial problem of all the old poems: there’s so much variation between manuscripts that it’s impossible to say what the poet intended.

Miracles occurred at Hampole when the nuns tried to have Rolle canonized. His fame revived just before the Peasants’ Revolt, when Lollard influence was increasing. (Lollard, from lollen, to loll or idle, was applied to street preachers.) His writings were exploited by reformers. Around 1378 his commentary on the Psalms was reissued with Lollardish interpolations. No one knows who revised it: some point the finger, implausibly, at John Wycliffe. Though not a poet, though his works are as confused in attribution as Rolle’s, though exploited, celebrated and reviled for centuries after his death, Wycliffe is one of the tutelary spirits presiding over our history. He made it possible not only for King David to sing in English—there were English versions of the psalter before Rolle—but for Moses and Jesus and God to use our vernacular, for the Bible as a whole to land on our shores in our own language. Suddenly English is good enough for Jesus. It has become legitimate.

The Black Death returned again and again. “Servitude was disappearing from the manor and new classes were arising to take charge of farming and trade.” Thus G. M. Trevelyan tells it, making it part of an abstract process, draining it of human anguish and spiritual vertigo. “Modern institutions were being grafted on to the mediaeval, in both village and town. But in the other great department of human affairs—the religious and ecclesiastical, which then covered half of human life and its relationships—institutional change was prevented by the rigid conservatism of the Church authorities, although here too thought and opinion were moving fast.” They were provoked by the intransigence of men who governed and profited by the Church. These visionless administrators alienated free spirits and the intellectually dissatisfied. The voice of Wycliffe begins to become audible. Church corruption is attacked by Chaucer, by Langland and (more gently) by Gower; but Wycliffe drives it home from the pulpit and in his writings, forcefully to the lay heart, and to the very heart of the Church. The Church is no more corrupt than other institutions, but its corruption is privileged, sanctioned and directed from abroad. The laity is more educated than in the times of Anselm and Thomas à Becket. The Church all the same prefers to ignore discontent and keep its monopolies and privileges intact.

Customs of fiefdom that constrained peasants on the land and preserved the feudal order of society no longer held. Too few men remained to do the work: survivors began to realize their worth, and then their power. They wanted more than they’d had: mobility, food—they even wanted wages. Peasants began to band together, recognizing power in community. The rich grew less secure in privilege. They sensed that they were dependents. Up to a third of the population perished in two years. When the plague returned in 1361, it was a plague of children. That year cattle suffered a new disease as well. The fever touched souls: many thought God spoke through that fire.

Reformers found a voice. Some spoke English. Before then, nobles and merchants had taught their children French from the cradle: “And provincial men will liken themselves to gentlemen, and strive with great zeal for to speak French, so as to be more told of”—a kind of social bona fides. But under Edward III change began, accelerating under Richard II. “This manner was much used before... and is since then somewhat changed. For John Cornwall, a master of grammer, changed the lore in grammerschool and construction of French into English... so that now, the year of our Lord a thousand three hundred four score and five, of the second kyng Richard after the Conquest nine, in all the grammerschools of England children leaveth French, and construeth and learneth in English, and haveth thereby advantage in one side, and disadvantage on another. Their advantage is that they learneth their grammer in less time than children were accustomed to do. Disadvantage is that no children of grammerschool conneth no more French than can their left heel, and that is harm for them if they should cross the sea and travel in strange lands.”

The plague was a catalyst. But transformation was not easy. One version of English could be more remote from another than French was. A northern and a southern man, meeting by chance or for business, would resort to French because their dialects were mutually incomprehensible, as much in diction as in accent. English, a bastard tongue, starts to move in the other direction from Latin. Latin broke up, but English began to coalesce. Dialects started to merge into an English language when scribes and later printers got to work and London usage became the idiom for written transactions. Those who made language public and portable, in the form of broadsheets and books, brought it, and eventually us, together. After a hundred years a young maid of Dundee and an old man of Devizes could hold a kind of conversation, not necessarily in limericks.

Much more than half our vernacular literature was northern before that time. Perhaps it still is, except the north has learned to parler more conventionally. English in its youth was hungry. The Normans imposed French but English was voracious even before they came, and in the courts of Cnut and Ethelred, when the Conquest was some way off, adjustments took place, influences from the Continent resolving the knots of a congested Old English idiom. We swallowed French (digestion altered us). The Conquest meant that English in its various forms had to gobble up faster. Written texts can be more conservative than speech: there is authority in formality. It is a risk to use the language of the day for important matters because it’s in flux and you never know which dialect, which bits of diction or patterns of syntax, will prevail.

Trevisa’s translation of the Polychronicon reflects how “it seemeth a great wonder how English, that is the birth-tongue of Englishmen, and their own language and tongue, is so diverse of sound in this land,” while Norman French, a foreign idiom, is the lingua franca of the islands. In Trevisa’s own translation, which makes sense when read aloud, Higden writes: “For men of the est with men of the west, as hyt were vnder the same party of heuene, acordeth more in sounyng of speche than men of the north with men of the south. Therefore hyt ys that Mercii, that buth men of myddel Engelond, as hyt were parteners if the endes, vnderstondeth betre the syde longages, Northeron and Southeron, than Northeron and Southeron vnderstondeth eyther other.” But it’s the “Southeron” language that prevails. The “Northeron,” Higden says, is scharp, slyttyng, and frotyng—harsh, piercing and grating. The birthplace of a prejudice.

Foreign affairs continued to be conducted during the plague as if there was no crisis at home. Skirmishes, battles and wars in France, Spain and Scotland, cruelty and piracy on every side. There was death by disease and on the field. England was certainly part of Europe. Sick at home, Englishmen went abroad to bring back wealth; they were preparing for their defeat. Edward III died in 1377 and was succeeded by Richard II, a boy who grew to a colorful, corrupt majority. Demands on poor and common people grew: demands for tax, service, subjection. The Peasants’ Revolt had urgent causes, though it was too early in history for the masses to rise successfully against a king. It was high time—Richard II knew it quite as well as Gower—for the court and the masters to learn to speak and sing in the language of their people.

Fortunately there was more to build on than Richard Rolle of Hampole. There was Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, the English ballads and dozens of vulgar translations of French works. There are poems the scholars will never find, ballads and lyrics, elegies, poems of moral precept, religious meditations, lives of saints... Were they lost because they weren’t worth keeping, or because they were so constantly used that they were thumbed to pieces? Parchment wasted with the hungry love of reading eyes, recitation, with handing back and forth between poets and scholars and minstrels. Were they lost when, at the Reformation, great libraries were burned, or emptied out and sold to the local gentry—as the wicked and wonderful biographer and gossip John Aubrey remembers with pain—to be twisted into plugs for wine casks, sliced into spills to start fires, or cut in convenient sheets as bog parchment?

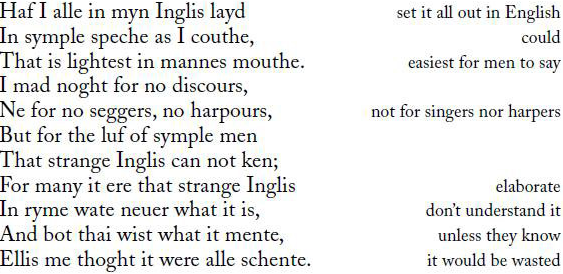

Reading English in the first half of the fourteenth century was a furtive activity, frowned on by authority. When Edward III came to the throne English was revalued; from being the underdog’s tongue it became the chosen instrument of Geoffrey Chaucer. Robert Manning of Brunne had used what would become Chaucer’s and Gower’s tetrameters almost fifty years before, with a mechanical awkwardness that Gower corrected. Handlyng Sinne was based on a French work by the English writer William of Wadington, the Manuel de Pechiez—a book Gower used too. Manning explained his purpose in his Chronicle of England, completed in 1338:

The lines are end-stopped, little breathless runs. One can respond to them but their value is local. Crude stuff, the language not up to much, but it starts clearing a space. The same is true of the Scot John Barbour’s vast limping history The Bruce, begun in 1372, where the lines do not pause but halt on a proud and assertive (if sometimes approximate) rhyme, often achieved with great violence to the word order. Yet he, too, prepared the way and Scots still have his book in their library of classics, though I suspect few actually read it, apart from schoolchildren who endure their “distinctive heritage” being rammed down their throats.