CLANSMEN are normally depicted wearing the belted plaid, a large expanse of tartan material elaborately pleated around the waist with the surplus material thrown over the shoulder. Then above the waist is a jacket, cut short to accommodate the folds of the plaid and under it a linen shirt; if a more heroic appearance is required the coat can be dispensed with and the short sleeves rolled up to expose brawny arms wielding a broadsword. This familiar picture is, however, completely contradicted by the discovery of two fully clothed bodies, buried in peat bogs as far apart as Quintfall Hill in Caithness, and Arnish Moor near Stornoway in 1920 and 1964 respectively.

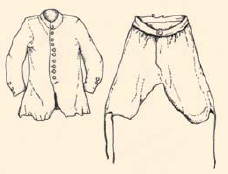

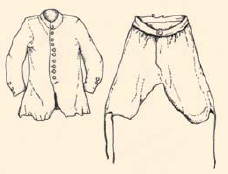

The first of these men was actually wearing two complete suits of clothing, one on top of the other. Each comprised an ordinary pair of breeches and a hip-length coat or jacket. He had a bonnet, not knitted but formed from pieces of cloth, and his stockings were likewise pieced up rather than knitted. There was no trace of a shirt although this is most likely due to the linen having completely rotted away. A plaid was also found with this body and coins found in the man’s pocket indicate he must have died at some time during the 1690s. But if the style of his clothing and the wearing of ordinary breeches rather than a belted plaid or trews runs counter to what we would expect a Highlander of that time to be wearing, the other body from Arnish Moor turns this expectation completely on its head.

Dating to just a few years later, he was a young man wearing two knee-length woollen shirts, one on top of the other, and a hip-length woollen coat lined with the remains of an older one. There was a blue bonnet upon his head, knitted this time, and a pair of much patched knee-length stockings upon his legs, but he had no breeches and there was no sign of a plaid. This might be puzzling if it were not for the fact that a man dressed in exactly the same fashion, with a jacket and long over-shirt but neither plaid nor breeches, can be seen standing in Inverness market place in one of the sketches illustrating Edward Burt’s Letters from the North of Scotland, from the 1730s.

In beginning the story of Scottish dress we therefore need to start with the shirt, for that was the main garment described by all the early writers.

From Quintfall Hill in Caithness came this complete suit of clothes from a man reckoned to have been murdered there in the 1690s.

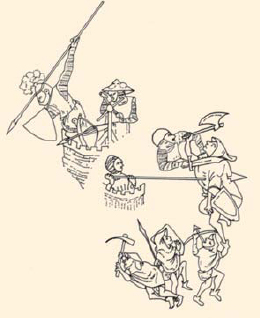

Magnus Berfaet’s Saga tells how when King Magnus of Norway returned from the Western Isles in 1093, he and many of his followers had adopted the costume in use there: they went about bare-legged wearing short tunics and ‘upper garments’. Magnus and his men therefore no doubt looked very like some of the Scots sketched on an early charter of Carlisle dating to 1316, just two years after the battle of Bannockburn, but what is interesting there is that while the Scots all wear long over-shirts, it is most unlikely that any of them were Highlanders – which reinforces the point that in those early days there was little if any distinction between Highland and Lowland Scots.

One of McIan’s splendid illustrations labelled as a chieftain of Clan Fergusson but actually based on a print depicting an Irishman wearing a saffron war shirt.

This Scots bowman slain by Sir Andrew Harcla has a hooded shirt and a common style of ‘kettle’ helmet, so called because it was used both for protection and cooking.

Moving forward two hundred years, however, sufficient differences were emerging for a Berwickshire laird named John Major (or Mair) to describe specifically Highland dress in 1521:

From the middle of the thigh to the foot they have no covering for the leg, clothing themselves with a mantle instead of an upper garment and a shirt dyed with saffron …. In time of war they cover their whole body with a shirt of mail of iron rings, and fight in that. The common people of the wild Scots rush into battle having their body clothed with a linen garment manifoldly sewed and painted or daubed with pitch, with a covering of deerskin.

One of the earliest known depictions of Scots is a sketch on the Carlisle Charter showing Sir Andrew Harcla beating off an attack by men wearing shirts and mantles.

Highland bowman of the sixteenth century by McIan.

Similarly, Jean de Beaugué, a French soldier who served in Scotland in the 1540s noted, ‘They wear no clothes except their dyed shirts and a sort of light woollen rug of several colours’, while Lindsay of Pitscottie in 1573 likewise stated that they (Highlanders) ‘be cloathed with ane mantle, with ane schirt saffroned after the Irish manner, going barelegged to the knee.’ Then Bishop Leslie, writing just five years later in 1578 said much the same, but in rather greater detail:

Their clothing was made for use (being chiefly suited for war) and not for ornament. All, both nobles and common people, wore mantles of one sort (except that the nobles preferred those of several colours). These were worn long and flowing, but capable of being neatly gathered up at pleasure into folds. I am inclined to believe that they were the same as those to which the ancients gave the name of Brachae. Wrapped up in these for their only covering they would sleep comfortably. They had also shaggy rugs, such as the Irish use at the present day [1578], some fitted for a journey, others to be placed on a bed. The rest of their garments consisted of a short woollen jacket, with sleeves open below for the convenience of throwing darts, and a covering for the thighs of the simplest kind, more for decency than for show or defence against cold. They made also of linen very large shirts, with numerous folds and wide sleeves, which flowed abroad loosely to their knees. These, the rich coloured with saffron and others smeared with some grease to preserve them longer clean amongst the toils and exercises of a camp, which they held it of the highest consequence to practice continually.

Another of McIan’s paintings of a northern Irish kern wearing a voluminous saffron war shirt.

The way Highland gentlemen proclaimed their superior status by the wearing of bright saffron yellow shirts, or rather over-shirts, did not always produce the happiest of results, as the unfortunate Angus Mackintosh of Mackintosh discovered to his cost in 1592. While he and some of his clansmen are preparing to attack Ruthven Castle in Badenoch, we are told, one of the Earl of Huntly’s men ‘creeps out under the shelter of some ruins, and levels with his piece at one of the Clan Chattan cloathed in a yellow war coat (which amongst them is the badge of the Chieftaines or heads of Clans) and … strikes him to the ground.’

One of Burt’s illustrations from the 1720s or 1730s, this time depicting fishermen being carried to their boats – to avoid spending all day at sea with wet feet.

Thus fell the Laird of Mackintosh and oddly enough so did the practice of wearing yellow war coats. Nevertheless the sudden disappearance of saffron shirts does not seem to have been a prudent response to the realisation that they made splendid targets, but rather the reflection of a shortage of dyestuffs and fine linen from Ireland as a result of the Elizabethan conquest. It certainly did not result in the disappearance of the over-shirt itself, for apart from the evidence of that murder victim from Arnish Moor and illustrations by Burt and others, the Reverend Mr Ferguson, minister of Mulmearn, recalled that in 1715:

Those Highlanders who joined the Pretender from the most remote parts of the Highlands, were not dressed in parti-coloured tartans, and had neither plaid nor philabeg, but that their whole dress consisted of what we call a Polonian or closish coat, descending below mid-leg, buttoned from the throat to the belly, and below that, secured for modesty’s sake with a lace towards the bottom. That it was of one colour and home made, and that they had no shirt, shoes, stockings nor breeches.

A ‘Wild Scotsman’ after Lucas de Heere, from the 1570s. The original shows a pinkish brown mantle worn over a yellow shirt with a fine chequered pattern, and blue-grey hose or breeches.

Another Highlander with a claymore, this time depicted by McIan wearing what is intended to be an early kilt – a garment unlikely to have existed in reality.

It was, in short, a pretty good description of the garment recovered from Arnish Moor. Be that as it may, there is a curious belief amongst some costume historians that with this sudden disappearance of the Irish-style saffron shirt, the mantle described as being worn with it was at once transformed from a nondescript cloak into what we now call the belted plaid. In a sense this is correct, but in a cultural rather than a practical context. Bishop Leslie had already described how the mantle was worn long and flowing, and was at the same time capable of being neatly gathered up into folds ‘at pleasure’.

The confusion arises because, as we shall see in the next chapter, the belted plaid eventually evolved into – or rather was replaced by – the kilt. Since the kilt is essentially a skirt-like garment now worn instead of trousers there has perhaps been a natural tendency to also view the plaid from the bottom up, and to see it first and foremost as a kilt or skirt worn between the waist and the knees with an upper part to cover the head and shoulders as well.

The claymore was carried on the back but not drawn from that position. Rather it was unbuckled and unsheathed before going into battle.

One of Koler’s Scots, wearing a broad blue bonnet and belted plaid. The weapon by his right side is probably intended to represent a dirk.

This Scottish musketeer depicted by Koler is evidently a Lowland Scot, being unbearded and wearing tartan breeches which are too baggy to represent Highland trews.

Yet the key lies in the fact that all of those early observers chose to refer to plaids as ‘mantles’ and upper garments – robes worn over ordinary clothing either for protection from the cold or as an ostentatious display of their status. In part this was accomplished by showing off the colour and intricacy of their tartans, but it can also be seen most clearly in the early portraits of Highland chieftains. Where peers of the realm might choose to be painted in their robes of scarlet and ermine, and churchmen and scholars in equally sumptuous gowns, Highland chieftains chose colourful tartan plaids in a dazzling display of swank calculated to outdo them all. In those paintings the plaid is often arranged impractically in great flowing folds which deliberately imitate the classical Roman toga but reflect little of its practical origins. And it was not just the Highlanders who did so, for as the tartan assumed a wider political and cultural importance in the aftermath of the Union of 1707, otherwise conventionally dressed Lowland noblemen made a point of draping tartan plaids over their shoulders ‘for the credit of Scotland’.

This was no mere ‘Highlandism’ as would be seen in the next century, for at this time the plaid was worn all over Scotland, from the far north down to the border fells. The fact is that the plaid began not as an alternative to trousers at all, but as the equivalent of a heavy overcoat, worn out of doors in bad weather or on a journey or an expedition.

This Highlander depicted by McIan wearing tight-fitting trews forms a useful contrast to Koler’s musketeer.

An officer and sergeant of the Black Watch in the 1740s, identified by a sash and halberd respectively.

Appreciation of this simple point also explains of course why there are so many accounts of Highland soldiers throwing off their plaids before marching into battle, at Kilsyth in 1645 for example, or at Killiecrankie. Or for that matter, at Prestonpans in 1745, where Bonnie Prince Charlie was heard to laugh after the battle that his Highlanders had lost their plaids. Yet, given that their everyday dress was a large woollen over-shirt and a short jacket, throwing away their plaids had nothing to do with stripping off their clothing. Instead they were simply doing exactly the same thing all soldiers are wont to do: dropping their packs, blanket rolls and greatcoats and any other encumbrances and impedimenta before going into action.

A splendid evocation by McIan of the voluminous nature of the belted plaid, illustrating perfectly why it was discarded at home, at work or on the battlefield.

Nevertheless, once they themselves started to do some proper soldiering the plaid soon proved to be a less-than-ideal garb, as we shall see in the next chapter.

Highland Visitors – a propaganda piece from 1745 depicting clansmen in plaids being overseen by an officer in trews.

McIan’s rendering of an officer of the Sutherland Fencibles, a home service unit raised in the 1750s.