THE STORY OF THE KILT in the eighteenth century is at once well known, often vehemently disputed, and thoroughly misunderstood.

In March 1785 a letter, apparently written nearly twenty years before by a gentleman of unimpeachable veracity named Evan Baillie of Aberiachan, appeared in the pages of the Edinburgh Magazine, asserting:

About 50 years ago, one Thomas Rawlinson, an Englishman, conducted an iron work carried on in the countries of Glengarie and Lochaber; he had a throng of Highlanders employed in the service, and became very fond of the Highland dress, and wore it in the neatest form; which I can aver as I became personally acquainted with him above 40 years ago. He was a man of genius and quick parts, and thought it no great stretch of the invention to abridge the dress, and make it handy and convenient for his workmen: and accordingly directed the using of the lower part plaited of what it called the feile or kilt … and the upper part was set aside; and this piece of dress, so modelled as a diminutive of the former, was in the Gaelic termed felie-beg and in our Scots termed little kilt; and it was found so handy and convenient, that, in the shortest space, the use of it became frequent in all the Highland Countries, and in many of our northern Low Countries also.

Needless to say the suggestion that the kilt was invented by an Englishman inspired a great deal of controversy and downright indignation, both at the time and afterwards. However, while the story as it appeared in the Edinburgh Magazine is well known, John Sobieski Stuart wrote a slightly different version in his magisterial 1845 Costume of the Clans, which he stated was told to him by various old people in the Glengarry country.

An Englishman named Rawlinson was indeed the manager of an ironworks, sited to take advantage of the extensive birch woods near Bridge of Garry, which provided the fuel necessary to feed the furnace. The kilt was devised and sewn for him by a regimental tailor named Parkinson from the nearby garrison of Fort William and when Rawlinson strode forth wearing it, old Ian MacAlasdair Mhic Raonuill of Glengarry ‘caused a second to be made for himself’. There is no mention in this version of the kilt being made for Rawlinson’s workmen, who were in any case not foundrymen but woodcutters. More importantly it was at the time being worn by just a few albeit by the rising of 1745 it had become sufficiently popular to be included as the ‘Philabeg, or little Kilt’ in the Act of Proscription that followed.

This well-known image of one of the first Highland soldiers in the British Army appeared in the 1742 Cloathing Book.

This sketch after an unknown artist from Penicuik in 1745 might serve as a rear view of the preceding figure.

As it turned out, the crucial part of that Act was not the mere mention of philabegs but the way in which it exempted those in the service of the Crown from its provisions. Thus began the Highland regiments’ custody of the kilt and tartan. Tailors, outfitters and other pundits might express their opinions as to the appropriateness of garments or accoutrements for particular occasions, but ultimately it is those regiments which are the true guardians and arbiters of everything we now recognise as Highland dress – and that includes the kilt. Notwithstanding the impression given in both versions of the story as told above, the kilt is not simply the old belted plaid with the upper part cut away.

A typical Highland gentleman of the period shortly before the ’45, depicted by McIan wearing a ‘figured’ (embroidered) waistcoat, short coat and belted plaid.

We are told that when a Highlander donned his plaid he first laid it out flat on the ground or the floor. A belt was then passed underneath it at what would be his waist level when the bottom edge lay at the tops of his knees. The material was then gathered into pleats at right angles to the belt until both ends of it became visible. At this point the clansman lay down on the pleating, crossing and securing the belt and material over the front, before standing up and throwing the rest of it over his shoulder, or securing it by a button or a pin by the neck.

In contrast to the well-groomed reconstructions by McIan, this contemporary sketch of MacDonald of Keppoch by the Penicuik artist evidences a much wilder figure.

Similarly this portrait of an unidentified but strong-minded character provides once again a good impression of how the plaid tended to gape at the front.

With practice this can be done surprisingly quickly and easily. It takes little imagination to work out where the belt should go by reference to the tartan, while the pleating is folded along an easily determined sequence of vertical lines. There are, however, a number of drawbacks not always apparent from formal portraits. Belting the plaid this way is all very well on a floor or a flat piece of dry ground; when it is wet and windy it is easier and a good deal quicker to throw the whole lot over the shoulders and then roughly gather it in around the waist, especially if a heavy over-shirt is being worn underneath anyway.

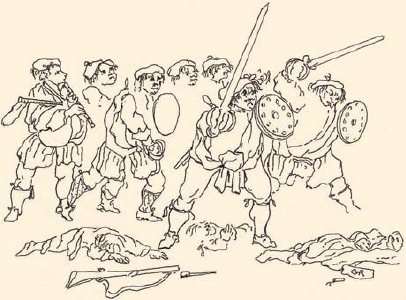

Highland clansmen in action in 1745 as sketched by the Penicuik artist. Note again the characteristic ‘gape’ at the front, of the plaid, barely covered by the sporran.

Labelled by McIan simply as a gentleman of Clan Cameron, this figure appears to be intended as Cameron of Locheil himself as he may have appeared in the ’45.

This sketch after the Penicuik artist is a useful reminder that Scottish dress could often be significantly less elegant than sometimes imagined.

Even if the plaid is put on properly there are two other problems to contend with. In the first place, because the greater part of it is still above the waist, there is a pronounced tendency for the kilted part to be dragged upwards, thus increasing the gap between the knee and the bottom hem. Secondly, although the material should ideally overlap at the front like the modern kilt, there is instead a tendency for the two sides to drift apart. Dignity was then preserved by the sporran and the way in which (as some portraits show) the pleats or kilting are carried all the way around, rather than leaving a flat ‘apron’ at the front. Nevertheless, contemporary illustrations almost invariably depict both a gap at the front and a far greater expanse of naked leg than might be expected in the civilised world.

The result of this is that however useful and comfortable a plaid might have been when worn by an individual, it was thoroughly unsuitable for regular soldiering. At home a man could discard his plaid, either to dry it out in front of a fire or simply lay it aside in warm weather, and then wander around in his shirt tails. Not so in the army. Even when the plaid was worn, achieving a smart and military appearance on parade was possible but required too much care and attention to ensure that each one was pleated, hung and pinned in a smart and soldier-like manner.

Hence the attractions of the kilt were obvious, for it preserved the basic elements of the regimental uniform – King George’s red coat above the waist and King George’s dark tartan below – but was far quicker to put on and far less cumbersome to wear. In the 1750s Highland orderly books were directing that when a new plaid was issued, the old one was to be cut down and sewn into a kilt, worn on all but the most formal occasions. By the end of the eighteenth century, kilts were no longer being cut from old plaids but made up from new material, which is why in the 1790s the pattern books of William Wilson of Bannockburn, the great tartan weavers, show that the Black Watch had two tartans: the ordinary kilt tartan which featured a red overstripe (of which more later) and the plaid tartan which was of the more familiar Black Watch sett.

This gentleman seems intended as a portrait of the Jacobite general, Lord George Murray. Ironically he wears Murray of Atholl tartan – the Black Watch sett with a red overstripe.

Plaiding was woven on a 27-inch width rather than the 54-inch width of broadcloth, and consequently had to be doubled for a plaid. Kilts required just a single width and this reached up from just above the knees not to the waist but to the bottom of the ribs – where it remained until the arrival of denim jeans in the 1960s abruptly dropped men’s waistlines to the top of their hips. This material was then pleated and the top third of each pleat sewn down. The early pleats were still simple folds but once fixed in place it took no great stretch of the imagination to improve their appearance by pressing them flat with a hot iron to create box pleats.

One of McIan’s prints, this time very closely based on a pre-1745 portrait of James Drummond, Duke of Perth. Being a gentleman, dignity is preserved by his trews.

The classical elegance of Perth’s drapery contrasts markedly with the practical reality of this individual identified by the Penicuik artist as MacGregor of Dalnasplutrach.

A very useful illustration by McIan of the box pleating used in making eighteenth-century kilts, this time in the Grant tartan.

In very simple terms, if laid out flat a kilt comprises three equal-sized portions: a central pleated area, which forms the back of the garment, and two flat aprons which fold one over the other to form the front. When putting on the kilt the right-hand apron is first passed across the body and secured at the left, and the left hand piece is then passed over the top of it and secured on the right.

In the early days it was fastened with long pins and by way of preserving regimental tradition the Black Watch were still securing their kilts with pins at the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. The constant use of pins obviously did the material no good and as early as the 1790s buttons were being substituted, ribbon laces were common, and now straps and buckles are used. Whatever the form of fastening, it is used only at the top of the kilt and never at the bottom, which is unsecured to allow free movement. It is common for a pin to be worn low on the right leg, but this is attached to the outer apron by way of a weight to prevent it flying up, and is not used to secure it as the buckles do at the waist.

In time this simplest of kilts evolved further as the original box pleating gave way in the 1820s to knife pleating – and for some regiments to modern box pleating which is really a variant upon it. This demanded a great deal more skill from the kilt maker for it involved a significant change in the way the kilt was made.

At a distance the pattern of the unaltered government or Black Watch tartan is difficult to distinguish and it appears simply as a black or very dark greenish blue colour. The overstripes added by some regiments do stand out, however, and in order to tidy things up at the rear it is necessary to arrange the pleating so that either the same pattern of checks is displayed front and back, or else a closely spaced arrangement of the vertical stripes.

Whichever is preferred, this requires both more material and a fixed number of pleats to achieve the required appearance: twenty-two for the Camerons for example; thirty-one each for the Black Watch, Gordons and Argylls; and thirty-four for the Seaforths. This in turn meant that instead of simply being fitted around the waist with as many or as few pleats might be required by the girth of the wearer, it had to be tailored to fit, with excess material cut away from the top of the pleat. Far from being a matter of casually throwing a piece of cloth around the waist, the kilt was now something that required a craftsman to make it properly.

The kilt was worn by some of the Highland Light Infantry. The pipers had always worn it, as did all ranks of the 6th (City of Glasgow) Battalion.

The same kilt viewed from the right to show the two buckles used to secure the apron at the waist.

A rear view of the pleating. The Highland Light Infantry regained the kilt after the Second World War, only to lose it again on amalgamation with the Royal Scots Fusiliers.

The same again from the left, showing the single strap passing through the outer apron to secure the inner flap.

Bayonet drill as demonstrated in a modern reconstruction: a Black Watch officer from c. 1760 has his bayonet ‘charged’ towards the enemy.

A Highland soldier demonstrating bayonet drill in Major George Grant’s New Highland Military Discipline of 1757.

With Highland dress being regarded as synonymous with Scottish dress, it was adopted by a number of expatriate Scottish volunteer units. The Liverpool Scottish opted for Forbes tartan.