THE TRANSFORMATION of Highland dress into Scottish dress began with a determination to assert a distinct Scottish identity within the Union. James MacPherson’s poem cycle Ossian, a mighty epic of Gaelic heroes first published in 1762, exercised an enormous influence little appreciated today. It was MacPherson, rather than Sir Walter Scott, who first turned Highland clansmen into romantic warriors. In the process he also provided a culturally insecure Scotland with a highly distinctive creation myth and a romantic literary heritage firmly rooted not in the douce, respectable Lowlands of John Knox, David Hume and Adam Smith, or even in Scott’s beloved wild borderland, but in the infinitely wilder Highlands.

Both MacPherson and Scott would be vigorously condemned by the great historian Thomas Babington Macauley, who wrote of how ‘the vulgar imagination was so completely occupied by plaids, targets and claymores that by most Englishmen, Scotchmen and Highlanders were regarded as synonymous words.’ In more recent times, other writers such as John Prebble have joined with Macauley in denouncing the ‘sweet smell of romantic anaesthesia’ associated with the Highland revival. However, easy though it is to criticise the Victorian mania for tartans and everything that went with them, it is also true that it was the Scots themselves who most eagerly embraced this synonymity of tartans with ‘Scottishness’.

Respectability came first with a royal visit to Edinburgh by King George IV in 1822. The King himself was persuaded to wear a kilt, and Highland dress suddenly became fashionable.

As ever it was the Highland regiments that led the charge. During the Napoleonic Wars the need to expand their size meant there were insufficient Highland recruits to fill the ranks of all the kilted battalions. Englishmen and Irishmen would have to make up the balance and in order to accommodate them the decision was made in 1809 to take away the kilt from six of the regiments, including the Highland Light Infantry. The move was deeply unpopular, but as soon as the wars ended and the extra battalions were disbanded, those regiments set about regaining their Highland heritage.

Ostensibly a portrait of John Gordon of Glenbuchat of the ’45, this is a typical Victorian imagining, characterised by the intricate detailing popularised by the Sobieski Stuart brothers (see page 48).

More romanticism, this time in the form of a print by William Pyne depicting a Highland shepherd, c. 1800.

Kenneth Macleay’s triple portrait of Sergeant James Sutherland, Adam Sutherland and Neil Mackay, provides a very clear picture of the major elements of Victorian Scottish dress.

Another romantic view of Highland warriors, heavily influenced by pre-Raphaelism, and depicting the carrying of the corpse of Viscount Dundee from the field of Killiecrankie.

Grenadiers of the 42nd and 92nd Highlanders by Charles Hamilton Smith in the uniforms worn at Waterloo; note the red overstripe on the Black Watch grenadier’s kilt.

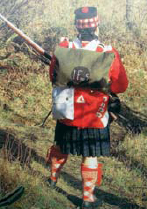

Rear view of a soldier from much the same period, in a modern reconstruction. Note the featherless or ‘hummel’ bonnet and the early box pleating of the kilt.

In 1820 the 91st obtained official sanction for the ‘Argyllshire’ title, and in 1823 the 72nd did one better, gaining both the title ‘Duke of Albany’s Own Highlanders’ and a suitably striking new uniform to match, combining Highland feathered bonnets with red trews or rather tartan trousers. Next, in April 1834 the 71st were also permitted to replace their plain trousers with Mackenzie tartan trews, and the officers were allowed the Highland scarf or shoulder plaid. The 74th were next, grudgingly designated as Highlanders once again in November 1845 and adopting a virtually identical uniform with so-called Lamont tartan trews.

In due course others followed suit, but then in 1881 something quite extraordinary happened. The government had for some time been working towards a complete re-organisation of the Army with a return to the two-battalion system. This time instead of raising additional battalions the existing ones were to be paired into completely new regiments. Thus the 42nd joined with the 73rd to become the First and Second battalions of the Black Watch; the 71st and the 74th became the Highland Light Infantry; the 72nd and 78th joined together as the Seaforths, the 75th and the 92nd merged as the Gordons, and the 91st and 93rd were transformed into the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. Thus amalgamated the new regiments obviously needed a new uniform, and with the exception of the Highland Light Infantry, all of them opted for the kilt. The HLI would have been glad to do the same, but their depot by now was in Lanarkshire and that meant that like the ‘Lowland’ regiments they were to wear tartan trews instead.

A good study by Victorian artist Harry Payne of a private soldier of the Highland Light Infantry.

The year 1881 therefore marks the point at which what had once been Highland dress officially became Scottish dress, for the Royal Scots, the Royal Scots Fusiliers, the King’s Own Scottish Borderers and the Cameronians all adopted tartan trews and Highland-style doublets, and soon acquired blue bonnets and pipe bands as well. So too did the volunteer and later the Territorial regiments associated with them, some of whom were even more enthusiastic about adopting distinctively Scottish uniforms. Two of the Glasgow-based HLI battalions even managed to turn out in kilts, as did one of the Royal Scots battalions from Edinburgh.

The Highland dress so eagerly adopted by these regiments (and indeed by everyone else proudly displaying their Scottish heritage) had evolved somewhat over the previous century and a half, and now it was going to do so again, at the same time becoming more formalised.

A Victorian gentleman with a fine set of whiskers and rakishly cocked Glengarry.

Although replaced by the kilt, the plaid itself survived as the feile (small), or ‘fly’, plaid. This was just a small piece of tartan material hanging down from the left shoulder to create the illusion of a belted plaid; during the Napoleonic Wars, officers whose duties required them to wear trousers rather than the kilt adapted it into a so-called Highland scarf. This was passed under the right arm, diagonally over the body and crossed over the left shoulder so that both sides dashingly hung down front and back. This is still worn today and is particularly favoured by pipers.

The 74th Highlanders lost their kilts in 1808 but nearly forty years later adopted what might be termed a modernised version of Highland dress.

Detail from Gibb’s magnificent Thin Red Line; it depicts the 93rd Highlanders at Balaklava and still forms a major iconic image of the Scottish soldier.

If the kilt and plaid thus preserved much of their original appearance the same could not be said of the bonnet. At first this was a simple round flat cap. Normally it was knitted and felted, although the one recovered from Quintfall Hill had been pieced together from cloth and in 1746 Lord John Drummond was described wearing a blue velvet one. Otherwise the only variation in style is reputed to have been a preference by Highlanders for smaller bonnets than those worn in the Lowlands. What is clear, however, is that although the first Highland regiments wore such bonnets in the 1740s, within a decade they began a dramatic process of change.

By the late 1750s the bonnet was being cocked up to reveal a decorative red band. This is sometimes said to have been a tightening tape but there is no evidence of this and in any case it was soon superseded by a rather broader chequered band. This is sometimes speculated to be a reference to the ‘fess chequy’ of the old Stuart coat of arms, but its true origin was more prosaic. At this point in time the bonnet was also being blocked up into a relatively high drum shape to present a more imposing and military appearance, and the chequered band was simply a decorative feature pleasingly mirroring the red-and-white checked hose worn below the knee. From its place of manufacture this became known as the Kilmarnock Bonnet.

This sergeant and drummer of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders appear in a remarkable series of very skilfully hand-tinted photographs of British soldiers in 1900.

Then came the feathers. In North America, when the bonnet was still low and flat, Highland soldiers had taken to sprucing it up by adding a tuft of black bearskin above the cockade worn on the left side. As the bonnet grew taller the bearskin tuft was replaced first by a single black ostrich feather and then by a spray of two or three feathers which had the dual advantage of rendering the bonnet far more imposing on parade, while still being light and easy to wear. The problem was that on their own they were too vulnerable to bad weather and bad usage.

At first the solution was to increase the number of feathers until eventually they overwhelmed it to become the dominant feature of what was now a headdress. Consequently, by the 1850s the original bonnet was replaced by an even taller version made of dark blue cloth stretched over a wire frame, still retaining the diced band around the bottom. The crown was rounded rather than flat at the top and once the ostrich feathers were attached to the outside the result was a much shaggier appearance – often mistaken for bearskin.

The feathers themselves were of two types: the relatively small ‘flats’ which formed the body, and the larger curved ‘fox-tails’ which hung down over the right ear. The Black Watch bonnets sported four of these, while the Seaforths, Camerons and Gordons had five, and the Argylls no fewer than six.

This group of officers belonging to the various Highland regiments dates to the 1860s but shows many features of Scottish dress still worn today.

Seventeenth-century Scots bonnets from Speyside (top; this may have been worn by a woman), from Arnish Moor near Stornoway (middle), and Quintfall Hill (bottom).

These were worn by all ranks until the First World War, but outside the Army feathered bonnets were and still are only associated with the larger pipe-bands. Everyone else managed perfectly well with more modest affairs. The ‘hummel’ or humble bonnet – a Kilmarnock stripped of its feathers – gave way to a much neater version, capable of being folded flat and still popular today as the Glengarry. The old flat bonnets remained popular as well and evolved into two styles: the smaller, softer of the two (conforming more closely to the popular image of what a Highland bonnet should look like) became the Balmoral, so named after Queen Victoria’s residence; the other, broader and flatter, inherited the name Kilmarnock bonnet and soon after the 1881 amalgamations became the headdress of the Lowland regiments. Both the Balmoral and the Kilmarnock are still traditionally knitted and felted and sport a diced band, but during the First World War were replaced on active service by versions pieced together from plain khaki material. The latter still survives as the ordinary headdress for Scottish soldiers, but by way of distinction is termed a Tam-o-Shanter (TOS).

Highland jackets at first closely followed contemporary fashion except in being cropped shorter to better display the kilt. That soon changed. The Victorian fascination with all things Highland demanded the development of a distinct style of jacket, or rather what was termed a doublet. While possessed of a suitably antique appearance this was both highly distinctive and yet practical. Below the waist there are a total of eight tabs, with two large ones (known for some reason as ‘Inverness Flaps’) on each side and a gap at the front to accommodate the sporran. The corresponding gap at the rear is filled by the remaining four, overlapping flaps. With the addition of gauntlet cuffs this style of doublet has survived unaltered for over 150 years as a dress jacket in the Army and a favourite with pipe bands.

A fine study of a Highland officer wearing a Glengarry bonnet.

Nevertheless it was regarded as too elaborate for everyday use. Fortunately in the 1870s the Army came to the rescue once again with the frock jacket. This was just a lightweight version of the tunic then worn by all soldiers, but instead of being square at the front it was cut away in a gentle curve to better display the kilt and accommodate the sporran. Again featuring gauntlet cuffs, this style is still very popular today in tweed or in a colour calculated to set off the chosen tartan of the kilt.

Thus by the end of the Victorian period Highland or Scottish dress had very largely assumed the form in which it appears today, and so too had tartans.

In this variation of the Gordon tartan once worn by drummers, red stripes fill between the paired black lines on the blue squares.