It all began in Palestine, in a small village outside of the city of Nablus, where I was volunteering for the skateboarding charity SkatePal in 2016. For the weeks I was living there, I used all my time outside of teaching the children how to skateboard, to travel around and experience as much of this unique place as possible. The buildings and structures of the occupation held particular interest for me: the concrete blocks surrounding bus stops, put in place to deter car-ramming attacks on Israeli settlers; watchtowers along all the major roads containing heavily armed soldiers of the Israel Defence Forces; tall wire fences surrounded Israeli settlement areas and, perhaps most famous of all, was the wall.

The separation wall was an imposing feature that cleaved the land in two. It stood nearly 8 metres (2.25 ft) high at points, constructed of solid concrete, and cast long shadows on to the land. Preventing free movement between the West Bank and Israel, the construction of the wall began after the Second Intifada of 2000, as a security measure following the subsequent wave of violence. It used the demarcation line known as the Green Line, drawn up in 1949 between Israel and its neighbours, as a guide. The Green Line was never intended to be an international boundary, which made the route the wall followed a complicated and controversial one. A 2009 report by the United Nations noted that the route the wall took annexed a total of 9.5 per cent of Palestinian land to the Israeli side. Separating farmers from their land, towns from their wells, and splitting communities, it has been condemned by the United Nations.

It was no surprise that, at points along the wall throughout Palestine, artists had been using it as a canvas to express themselves, to repurpose and subvert it, to retake ownership of the environment. I visited the wall at several points – Tulkarm in the north; the enclave of Qalqilya where the wall wraps almost completely around the city leaving just a narrow entry point; and Bethlehem, located to the south of Jerusalem.

Of all the locations, it was Bethlehem where the drips of graffiti had turned into a tsunami. Street artists from around the world had travelled to the wall to paint – artists whose work I would see in other cities on my journey following the story of painted cities: How and Nosm, Lushsux and, most famously of all, Banksy.

From my many conversations with Palestinians living in the West Bank, the predominant message was one of wanting to be heard by the world beyond the wall. There was a strong feeling of isolation, of being forgotten and ignored. Powerless. The internationally renowned artists choosing to shine a spotlight on the wall and the politics of the area, bringing the eyes of the world upon this place, had the ability to address this. The juxtaposition of world-famous works butting up next to the work of local artists, in addition to the messages left by visiting tourists, is striking – part ‘this is my story’ and part ‘we hear you’.

When I visited, it was estimated that street art tourism brought in more tourists than religious tourism to the city of Bethlehem. It was a tangible way in which the writing on the wall had given practical help to a community that had suffered under the image of it being too dangerous a place to visit. Multiple ‘Official Banksy’ shops were sprinkled around, created by entrepreneurial locals. As we walked the streets, a young Palestinian boy was chasing and yelling at another boy, waving a broom in the air above his head as he did so. It turned out that the one being chased had burst all of the balloons outside of his ‘Official Banksy’ shop. As we stepped inside, the young boy with the broom came back in to his tiny space, greeted us with a smile and gave us some biscuits. There was an original Banksy piece sprayed on the wall and protected with a sheet of Perspex, the shop erected around it selling snacks and drinks but also postcards and magnets featuring the more famous street art pieces of the city. I talked to him for a while, a little in Arabic and a little in English, bought a magnet and some postcards and left him to replacing the balloons.

Around the corner I found another Banksy-themed shop that sold spray cans in Palestinian red, green and black colours so that tourists could add their own messages to the wall. This had the effect of covering some of the more intricate street art pieces with scrawled names and supportive slogans. The volume of tags held a visual significance that was more powerful than aesthetics. Offering solidarity to people who felt forgotten, it was a reminder that they were not. I walked past the Walled Off Hotel under construction, another Banksy project that would reignite international interest in the area.

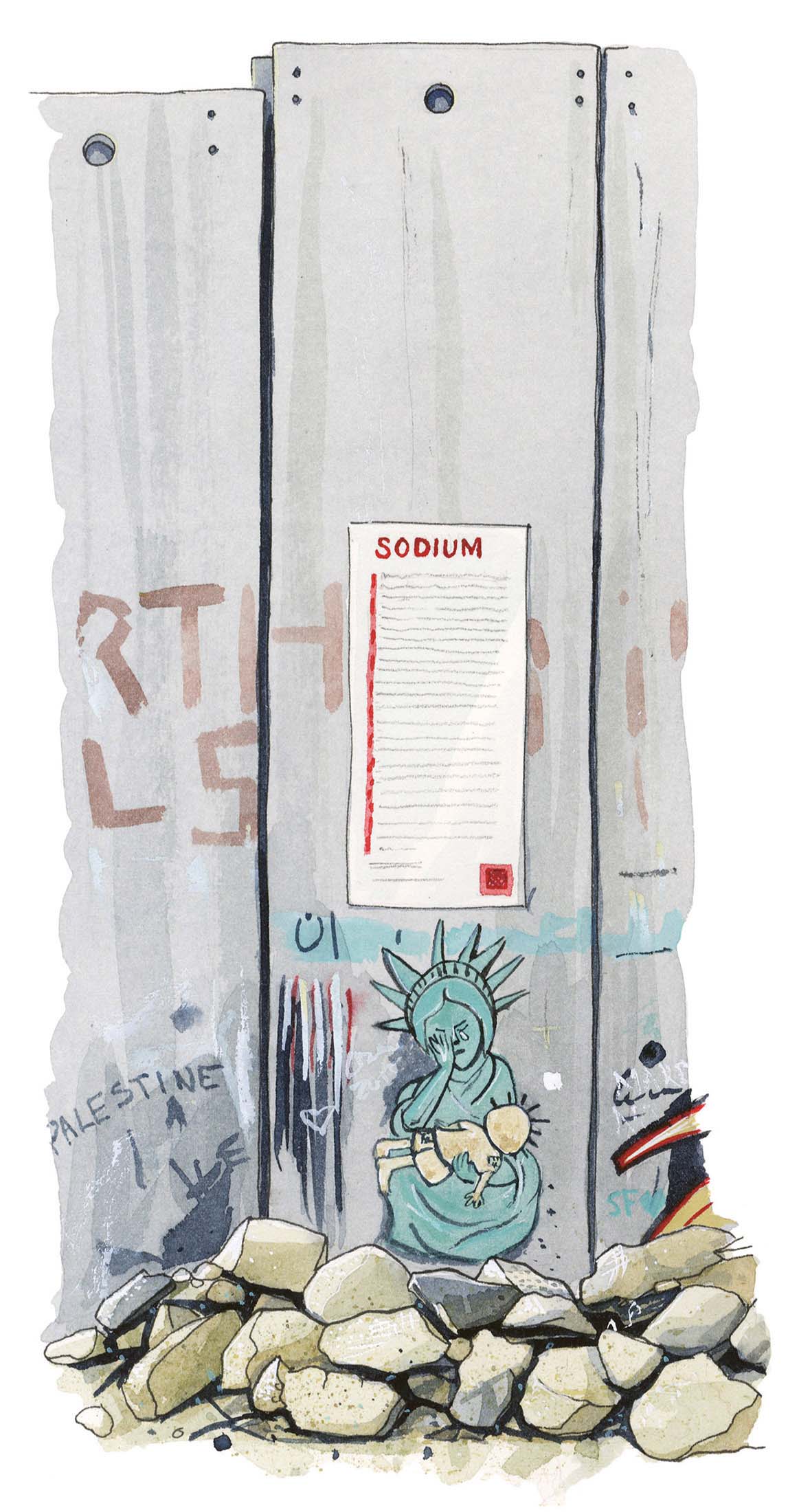

The wall was not just for visitors, it was also used as a way of letting local voices be heard. Along one stretch, white posters had been put up containing a series of written personal accounts from Palestinians living under its shadow – stories of tear gas and heartbreak. Another area had been painted white and was used as the backdrop for the projection of football games that the community could gather around, the huge surfaces of the wall converted into a giant TV screen. One of the most famous characters depicted on the wall at different points was the product of the Palestinian cartoonist Naji Salim Hussain al-Ali. The cartoonist created the image of a boy he named Handala, which became an icon of Palestinian defiance. Naji al-Ali was killed in 1987, but the spiky-haired character is still being painted in public.

Within Bethlehem, the painted walls were not limited to the towering separation wall. Aida Camp, the Bethlehem refugee camp created in 1950 to house refugees from Jerusalem and Hebron, covered a small area and was severely overcrowded. I had already visited a large refugee camp in Nablus called Camp No. 1, and been shown around the tight, dark alleyways of towering concrete buildings. The footprint of the refugee camps was not permitted to expand since their creation in 1950 so, to accommodate the growing population as new generations were born, the only place for the buildings to expand was vertically. At some points, the passageways were so tight that it was easy to touch both buildings on either side at once. Bullet holes peppered the walls, and I felt claustrophobic thinking of the regular raids by the Israeli military. I imagined the panic of being tear-gassed in a labyrinthine place.

I had also been staying in a hostel located in the centre of another refugee camp in Jericho, where the streets were wider and brighter and the place more closely resembled a small village. A number of shops were scattered around and there was an excellent falafel truck near the entrance to the camp where we ate each night.

The physical characteristics of Aida Camp were somewhere in-between these two versions. The Bethlehem refugee camp contained two schools, and the route to these schools was decorated with bright murals featuring colourful cartoon characters. They carried messages that reminded residents to resist, to be fierce, whilst simultaneously splashing colour in what would be a bleak concrete-and-dust environment. I walked by a wall with ‘We Will Return’ painted on it, below which were the names of the towns and cities that the refugees fled from in 1950. The attachment to the past whilst keeping hope for the future was one of the trickiest aspects of the political situation in this part of the world, and it was this dichotomy that was a regular theme on the walls. There wasn’t a clear answer to the problems people here faced, but for those who felt powerless, the ability to express themselves was a powerful outlet.

Banksy shop signs, Bethlehem.

How n Nosm, separation wall and tower, Bethlehem.

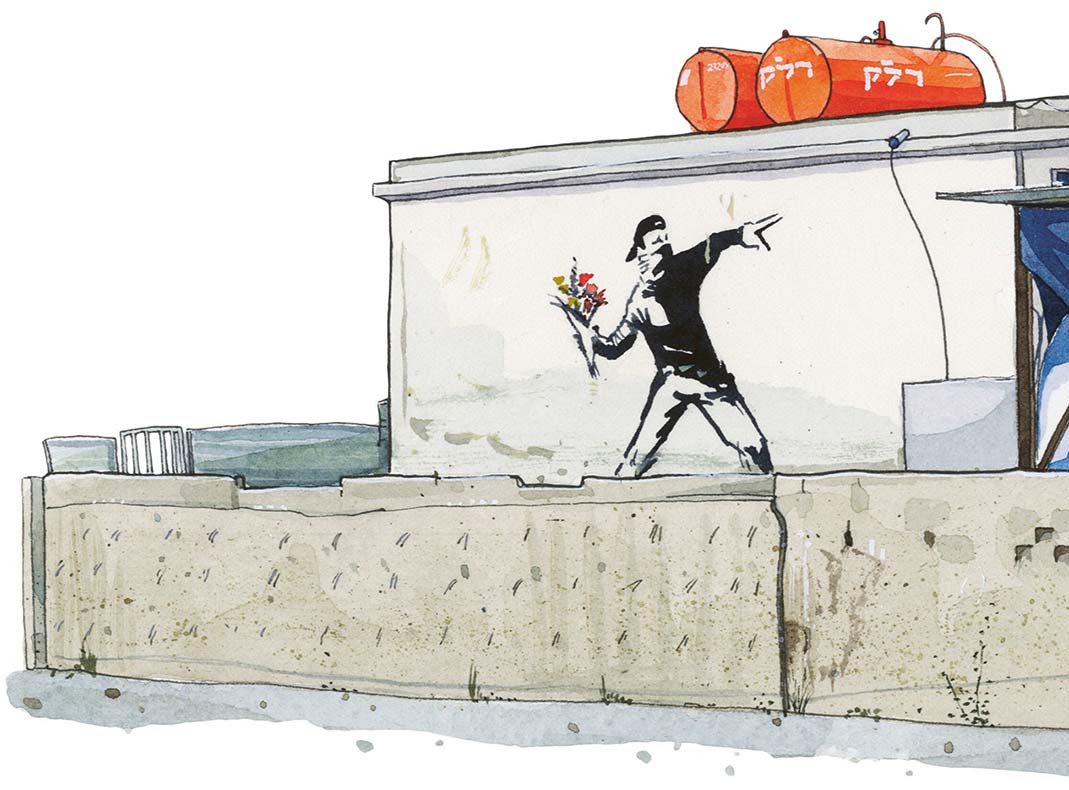

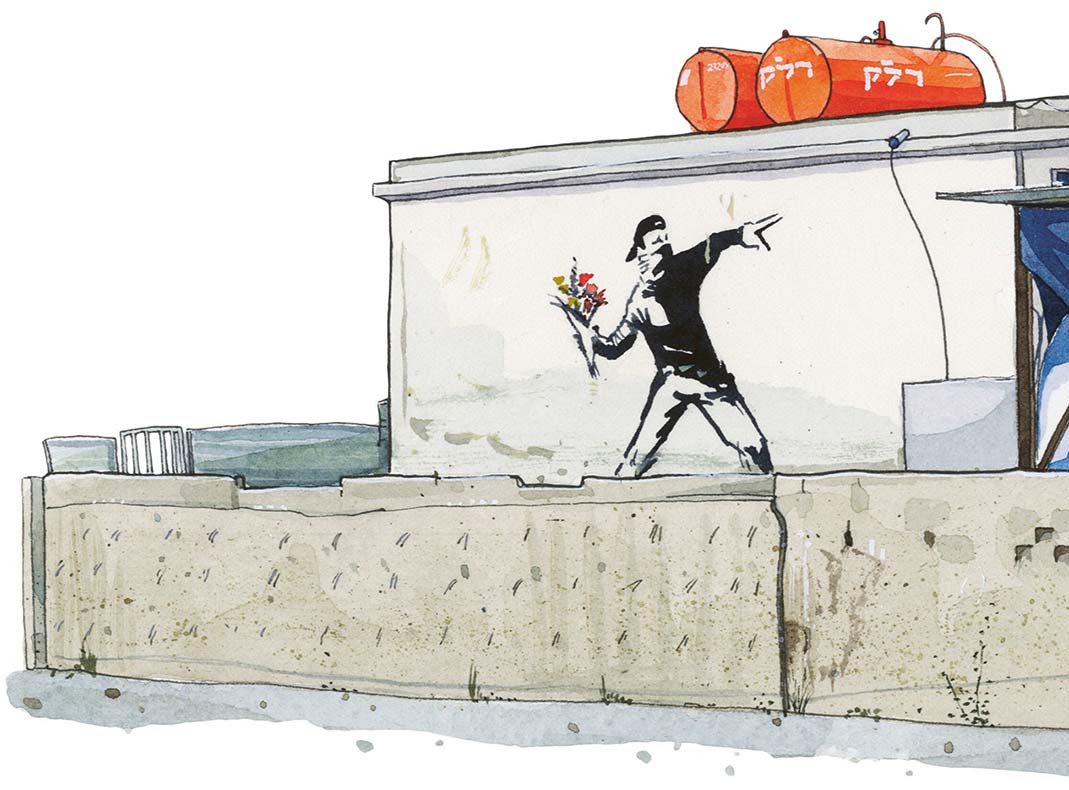

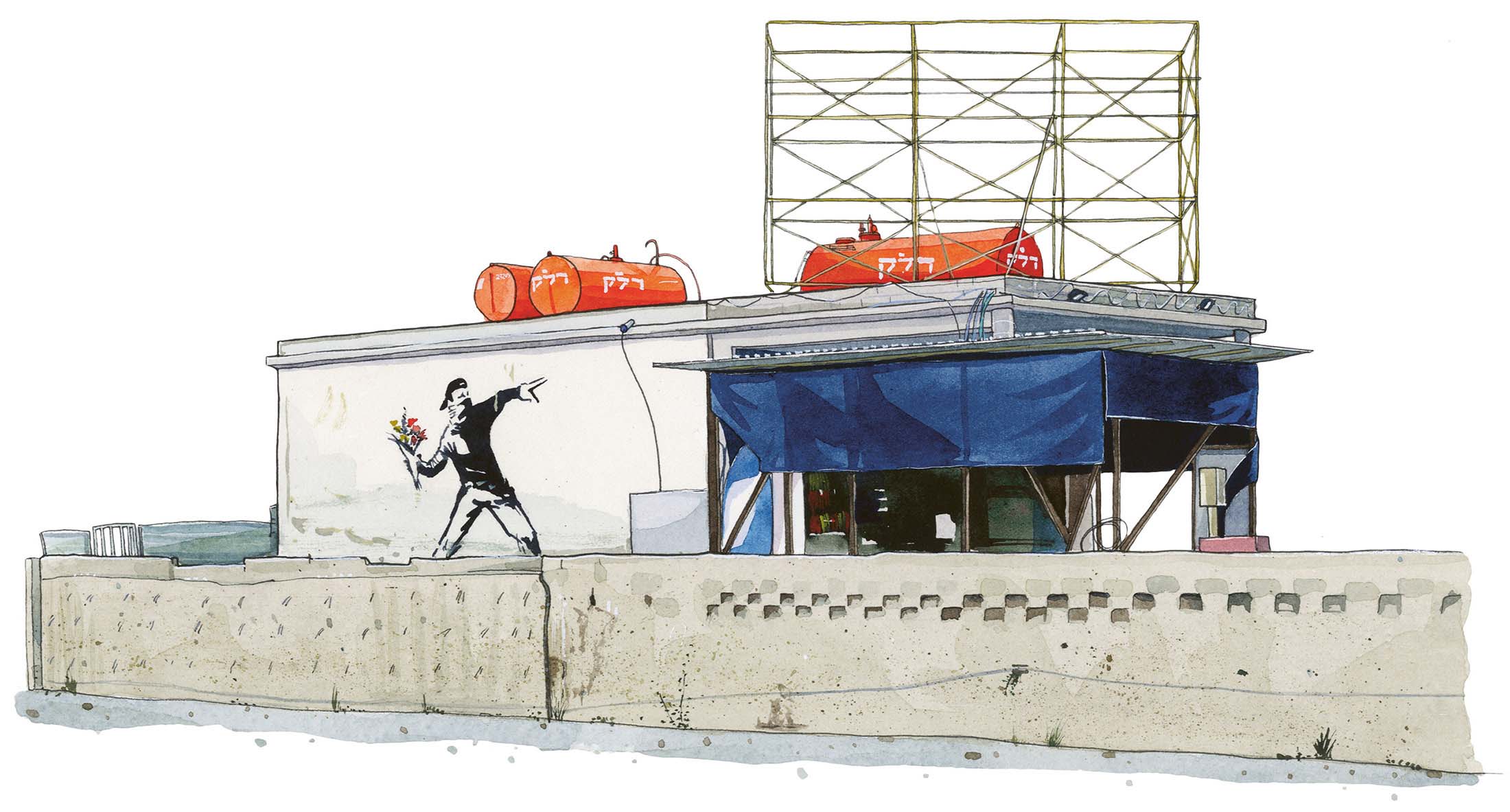

Rage, Flower Thrower, Banksy, Bethlehem.

Liberty and Handala, separation wall, Bethlehem.

Here, Only Tiger Can Survive. Aida Camp, Bethlehem.