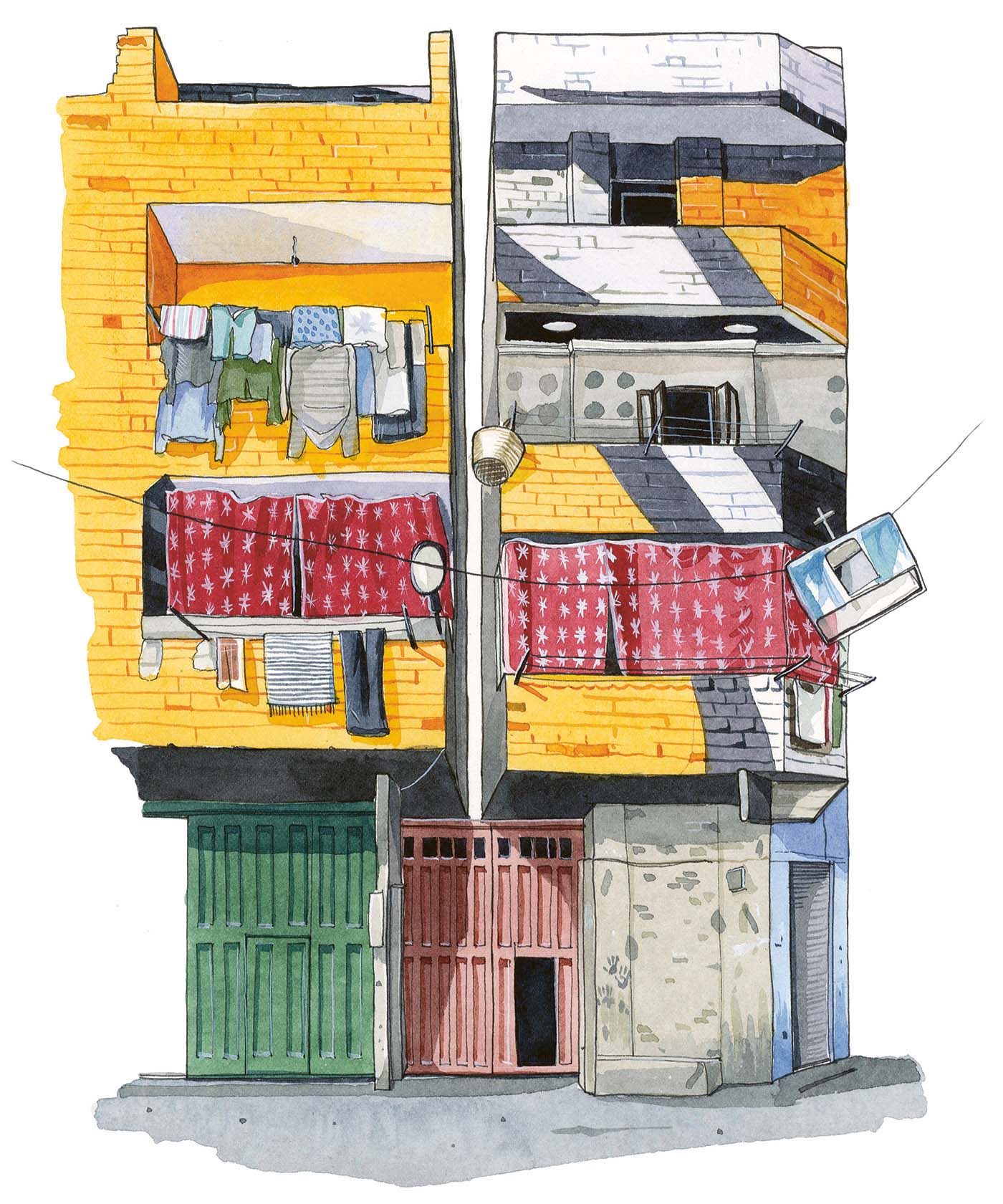

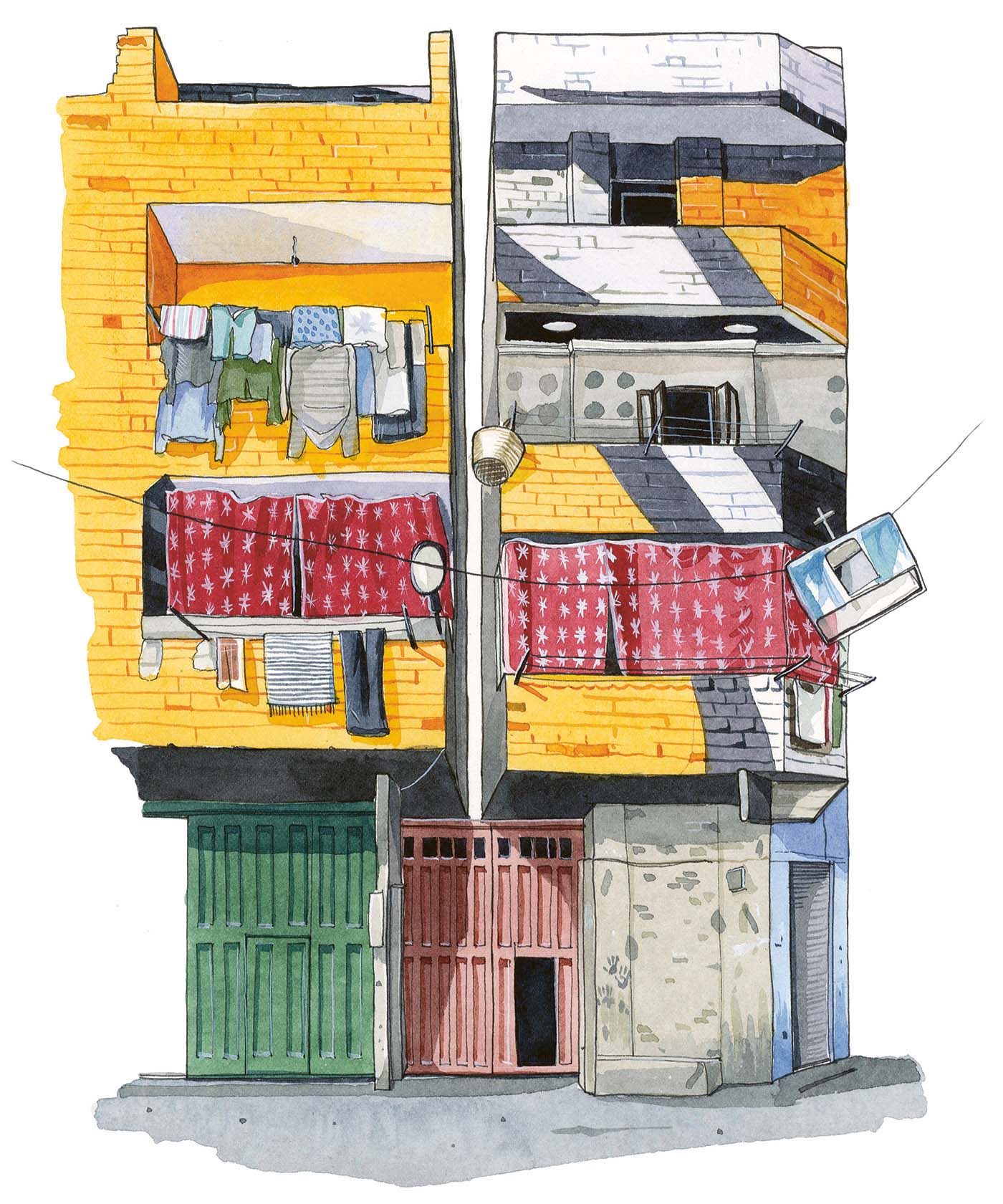

Perception detail by eL Seed. Zabbaleen village, Cairo.

Flying into Cairo I was struck by the sprawling expanse of the place. Peering out of my plane window I could see mile upon mile of sandy coloured high-rise buildings, carved up with curving and sweeping highways, all lined with giant billboards. Homes were stacked one upon another, reaching into the sky. There was a population of more than 20 million people in Greater Cairo alone, and it was densely packed.

I was travelling with my journalist friend, Jess, on this trip and we were staying with one of her Cairene friends, Laila, who lived in a stylish compound in the northeast of the city. Driving along in our cab, it felt good to be back in an Arabic country. I enjoyed the noise, the smells, the sounds, the traffic, the chaotic atmosphere and the familiar strangeness of it all.

On 25 January 2011, an uprising began in Egypt. It was the culmination of growing tension between the politically active youth movement and the established rulers. Millions of protesters took to the streets across the country to demand the overthrow of the Egyptian president, Hosni Mubarak, who had been in power since 1981. During the eighteen days of protests more than 800 people were killed and over 6,000 were injured. On 11 February 2011, Mubarak resigned as president. Whilst the protesters may have won this battle, the war was far from over. The power vacuum that followed, along with the collective grief of the people, did not bring about the Egypt that so many dreamed of. Too complex were the systems that needed overhauling following nearly thirty years of Mubarak’s rule.

The uprising was named a ‘Facebook revolution’, thanks to the use of social media as a form of mobilizing the youth. (There were similarly organized uprisings in Iran, Tunisia, Ukraine and Romania.) The power of young people working together to have their voices heard put a spotlight on the ways in which they communicate and resulted in street art within Cairo being seen as a political act. Even photographing street art in Cairo could land you in trouble – I had heard stories of photographers and journalists being asked to report to the authorities for doing exactly that. The city’s tough stance on graffiti brought to mind the Banksy piece in London from April 2011, not long after the Egyptian uprising, that said ‘If graffiti changed anything it would be illegal’.

The power of the younger population was not dismissed here. Art as a force to mobilize large groups of people was not underestimated. I wandered the streets and found very little sprayed upon the walls. Laila told me that anything painted on any of the buildings was usually buffed over very quickly. I passed one such wall that I knew was a prime location for pieces, but it was freshly painted and completely blank.

Perception detail by eL Seed. Zabbaleen village, Cairo.

Mohamed Mahmoud Street, near Tahrir Square, was the location of several of the more violent battles between protesters and the security forces and one of the few places that contained street art as a memorial to the clashes. I shot my reference of the work that was there as stealthily as possible, carrying my camera at my hip rather than my face, casually holding a conversation with Jess and Laila as I did so. The murals covered a long wall of what used to be the American University in Cairo (the Campus had moved), and across the street on the walls of the GrEEK Campus, previously part of the university but now home to tech and start-up businesses. Most of the murals were residual works from the 2011 to 2013 period. Hot sunshine had bleached the vivid blood reds of the paint to soft pinks, and the paste-ups were peeling and flaking. It felt allegorical of the uprising that had burnt so fiercely with many people dying on the streets, to where it was now, an undercurrent of glowing embers of disappointment and resignation; peace on the streets but not quite business as usual.

I walked the streets, dodging between five lanes of traffic as if I was in an advanced level of the Eighties computer game, Frogger. It was only after walking the streets for a long time that I started to tune in to the Martyr stencils. Scattered across the city, there were small stencil images of the faces of different people who had died or been injured during the revolution, often paired with Arabic phrases that Laila translated for me. ‘I am the evidence. I am the eye that was hit by fate and bled to death’ was one such phrase sprayed in red on the wall of a dilapidated print shop below an icon of a man with blood exploding from his eye socket. These Martyr stencils may have been subtle and small but they were fast enough to produce that they could be sprayed in large numbers, and the stencil format allowed multiple people to bomb the city in a single night – an example of the message being more important than the messenger. Cairenes were going about their business beneath them, occasionally catching a glimpse of a stencilled face reminding them that the fires of the past could not be completely extinguished or forgotten.

Having collected what I could from the centre of Cairo, I set off on a mission to find the multi-building mural called ‘Perception’, by the artist eL Seed, which he had completed in 2016. The piece was spread over almost fifty buildings within the Coptic community of Zabbaleen people in Mokattam Village below the Mokattam Mountain. Zabbaleen means ‘garbage people’ and they were given this name because of the important role they played in sorting through Cairo’s rubbish.

Laila helped me to hire a local artist couple to drive me to find and collect reference material of the piece. They arrived at the designated meeting point in a beaten-up white car. I climbed into the back seat and was greeted by a small kitten that they had rescued and who now lived in the car. The kitten, Dot, promptly curled up in my lap and fell asleep. We set off driving, with only the vaguest idea of where we were going. We had thought that a mural painted across fifty buildings would be an easy spot from the Mokattam Mountain, and an hour of driving later pulled up to a place where the mountains overlooked the high-rise buildings below. Looking out over the density of the city, I realized that the task of finding a vantage point of the mural might be harder than anticipated. We walked for a while along a dirt path that wrapped around the edge of the mountains, and I searched the surfaces of all of the buildings for any signs of the primary colours left by the hand of eL Seed. On the horizon I could just make out the Great Pyramids, blurry and indistinct thanks to the smoggy Cairo air. After some time hunting with no success, like a real-life Where’s Wally? book, we went back to the car and carried on the search elsewhere. We followed clue after clue for hours; my guides asked everyone they knew. One such clue came in the form of: ‘Find the church; the cafe above the church is where you can view it from. Ask for the cafe owner and he will let you in.’ There was no mention of which church, so we went to the one that my friends knew about – we found a cafe and it was locked. I could hear in their voices as they spoke to each other in Arabic that they were starting to panic. Whenever I asked if everything was OK, they turned and smiled and answered happily in English that everything was fine and we’d just try the next place. Eventually we reached a point late in the day when we all stopped where we were, all clues were exhausted, the sun getting lower in the sky. They looked at me and admitted that we were all out of leads. We headed back to the car that was parked by Tahrir Square. Back in the Cairo traffic, heading in the direction of the mountains again, their phone rang. It was an artist friend with another tip-off for the location to view the eL Seed piece from. Hope filled the car again and we drove back out of the city. This was our last chance. If this lead didn’t take us there, there would not be enough light to shoot the reference I needed to do the paintings, and I was flying back to London early the next day.

We drove up to the cave monasteries set into the side of the mountains, the roads narrowing the higher up we got, lined with towering piles of rubbish as we passed by the tiny openings to the maze that was the Zabbaleen village. We jumped out of the car and headed straight to the cafe. The young woman serving at the cafe window downstairs told us that upstairs was closed – but we hadn’t come this far to only come this far. We walked up a spiral staircase on the outside of the building and reached the locked door to the upstairs area. We knocked and waited. An old man answered, listened to our story and let us in. I followed behind him as we walked through the room and into another smaller room where all of the blinds were closed. At the very end of this room he opened a blind and the window. I stepped out from behind him, my heart beating hard. The view hit me: there it was, more breath-taking and incredible than I had even imagined. Lit up by the golden light of the low sun, narrated by the sounds of children calling pigeons back home to roost in the towers scattered across the rooftops, I folded in half and cried at the perfection of it. After so much heartbreak and sorrow following the story of the revolution, this expression of hope was the sweetest of tonics.

Mohamed Mahmoud Street, Cairo. Featuring work by Ammar Abo Bakr.

Martyr stencil, Cairo.

GrEEK Campus, Cairo. Featuring work by Alaa Awad and Abood.

Perception by eL Seed. Zabbaleen village, Cairo.