Mural by Berst, Gloucester Street, Christchurch.

Whilst visiting my family in Auckland, New Zealand, I took a plane down to Christchurch, a city dubbed the ‘street art capital’ of the Southern Hemisphere, in part thanks to its annual street art festival, SPECTRUM. Since the 2010–12 earthquakes that devastated much of the city, street art has been embraced and encouraged. Several people that I spoke to about the city said that it was young people who would keep the city alive, and who were most resilient to the years of aftershocks that had continued to shake the foundations of the whole Canterbury area. These millennials were priced out of the housing market across New Zealand, a whole generation of people forced to compromise and think creatively in order to establish any foundations for themselves.

It was just a short flight down to the South Island from Auckland. I was seated next to a man in his fifties who made regular visits to Christchurch on business. He had his own theory regarding when the earthquakes would hit the area, believing their timing related to spring tides – the period following each full moon and new moon when the tides are highest. He made every effort not to travel to the area during these dates, but this time found himself on a Christchurch-bound plane during a spring tide. He played with his cuffs nervously as we chatted about the mentality of the people who choose to continue living in a city where the ground writhed and groaned on a regular basis, or, where whole suburbs to the east of the city went from solid ground into flowing liquid thanks to liquefaction – a state where ground that was once stable was turned into a thick mobile soup.

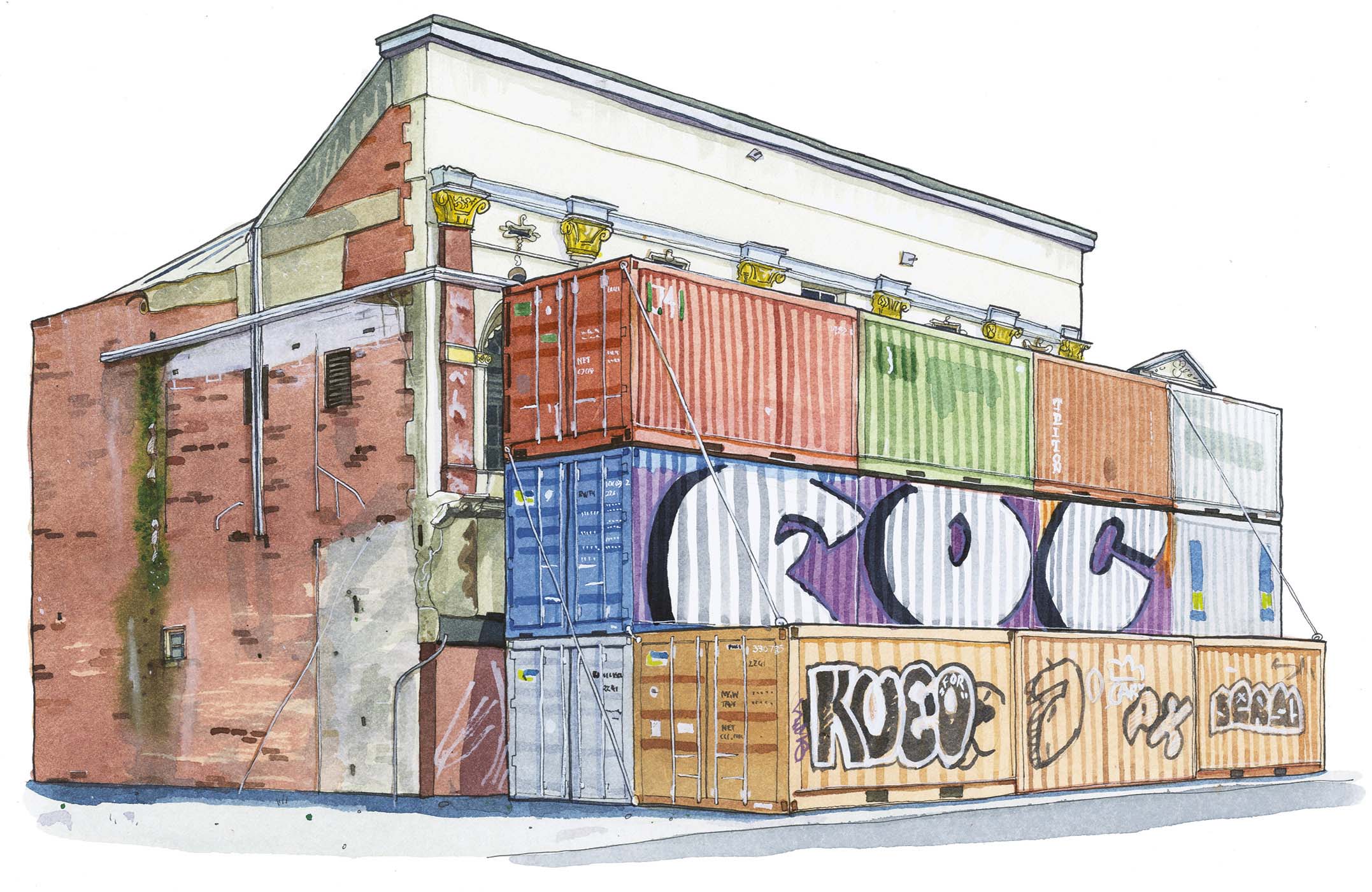

The conversation brought me back to a previous visit to the city, shortly after the 2011 earthquake, when I stayed at the house of friends in Sumner, a small suburb located at the base of Port Hills. The road outside the house was lined with shipping containers in a creative solution that would prevent further landslides and rock falls from crushing the small wooden houses. Back then, the rebuilding had yet to begin and many people were considering whether or not they wanted to stay. Between June 2010 and June 2012 the population had dropped by 2 per cent, and many more people wanted to leave but were trapped by lengthy insurance negotiations or stuck with homes deemed too dangerous to return to, even to collect possessions. On that visit, it had just been predicted that the city could expect another decade of aftershocks, enough to take its toll on anyone trying to plan how to rebuild their future.

If I felt distant from the concerns of global politics in Melbourne, this feeling was further increased in Christchurch. Global politics and terrorism were not even a blip on the radar – it was the ground beneath everyone’s feet that offered up the biggest personal threat. Nobody can win a battle against the earth, and so those who remained in the city out of choice instead of forced by circumstance seemed pretty chilled out.

Before the devastation, there was very little street art or graffiti in Christchurch, New Zealand’s oldest established city; the historic architecture, much of which was built in the late nineteenth century during the gold rush, was to be preserved and maintained – a living museum and snapshot into the narrative of such a newly colonized country. Tourists would come from around the world to gaze at the Christchurch Cathedral or the Gothic architecture of The Press Building. Spray paint and markers were unacceptable on the dark basalt blocks and the cream stone facings of the century-old structures. The 2017 version of the city had very little of this history still standing. So much care to preserve that identity, and it changed almost overnight.

Whereas in Cairo the purpose of much of the urban art was that of a reminder of the lives lost in the revolution, in Christchurch it performed the role of raising morale and providing a distraction from the giant building site the place had now become. Walking around downtown, the constant noise and agitation from the construction work felt oppressive and stressful. Seventy per cent of the buildings in the Central Business District had either been, or were scheduled to be, pulled down and replaced, which would leave a huge impact on the city. The footprints of demolished buildings were almost all turned into temporary car parks. A young city was springing up from the ashes of New Zealand’s oldest, and it carried with it a confusing identity. In any situation of great change or natural disaster there would be multiple responses from the community: those who saw it as an opportunity, those who wanted to take advantage, those who wanted to make the best of things, and those who wanted it to go back to the way it was. It was a fine balancing act for those in charge of rebuilding, attempting to keep the old aspects, whilst needing money from big business to fund construction. Regardless, if Christchurch wanted to survive in any form – and some people questioned whether it should, given the long-term prediction of at least another decade of earthquakes – it would need to maintain a population and stem the tide of people relocating to other places. It would have to attract a whole new set of tourists and the money they would bring into the area.

The introduction of urban art to the increasing number of derelict sidewalls of the city made perfect sense. Providing a colourful distraction to the grey rubble, they were messages of hope, and appealed to a younger generation who would accept the short-term compromises for a stake in the city, bringing with them tech companies and start-ups. ‘We Got the Sunshine’ by Olivia Laila and Holly Rocck fitted this role of brightening up the city perfectly. Other work, such as the mural on Gloucester Street by Berst, brought in elements of Maori mythology to further enrich the environment. From as early after the earthquakes as 2013, street art and murals were recognized as having the power to help transform the city. A group named Ministry of Awesome gave themselves the task of revitalizing it through the arts. The group said of their work in the post-quake city: ‘At a time when no one was looking, when people had ideas and room to play, we gathered together to activate our networks, break down barriers, cut through the red tape, and enable people to contribute to our city’. They teamed up with street art enthusiast George Shaw to explore the power that murals and urban art could have on the environment. In 2014, the work was added to with the first Rise Street Art Festival. Spectrum Street Art Festival made its way there in 2015 and 2016. By my visit in 2017, there were in excess of fifty murals around the city. The transient nature of urban art synchronized perfectly with the ever changing and evolving demolition and rebuilding that was happening. It also acted as a magnet for a new form of tourism and made Christchurch a destination again.

Mural by Berst, Gloucester Street, Christchurch.

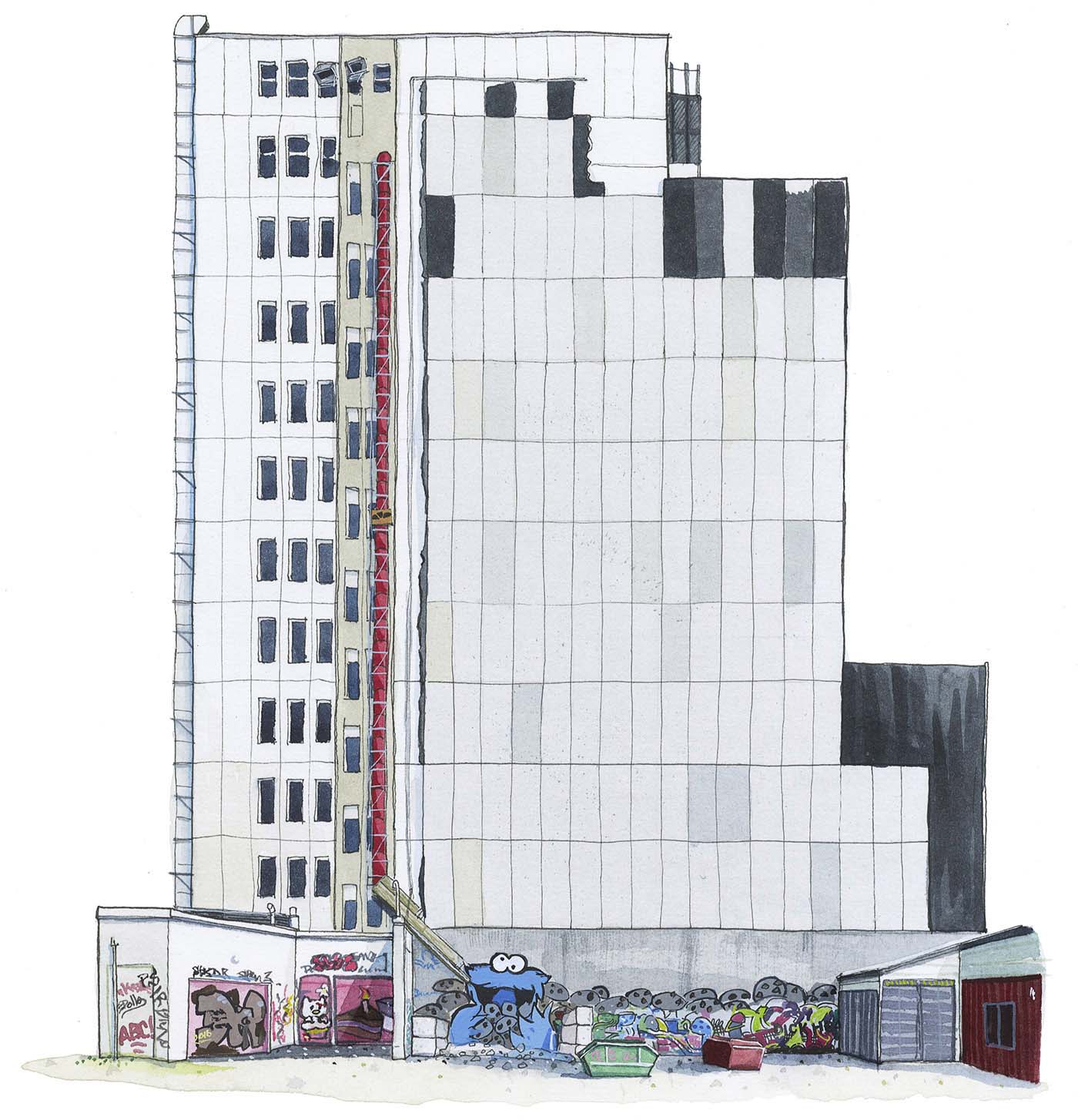

Cookie Monster, Christchurch.

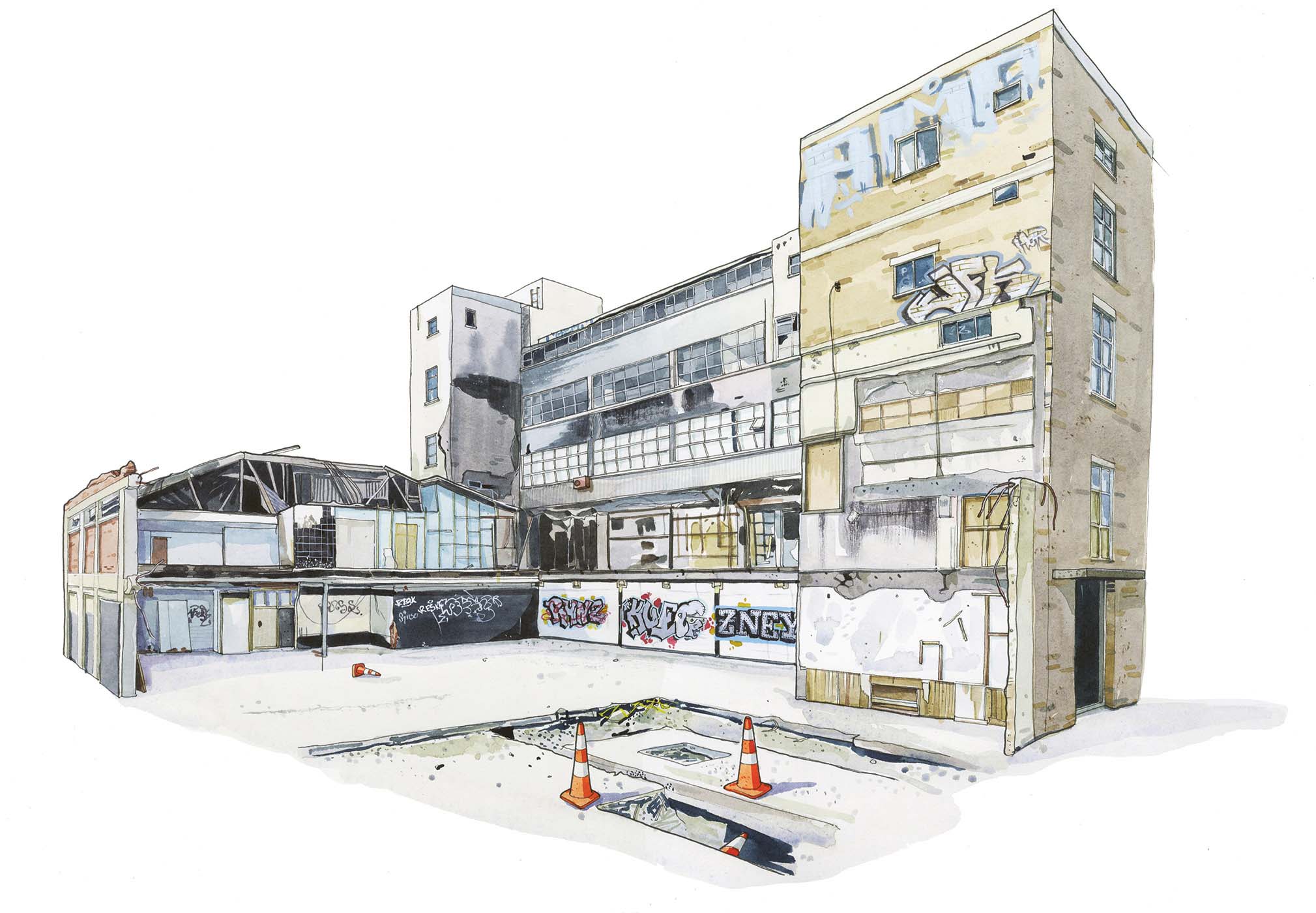

As I navigated the city, I noticed how everything being a building site blurred the boundaries of private property. Cones and wire fences were much easier to cross and explore behind than locked doors and inhabited spaces if you were perpetually curious. I climbed fences to get better views of murals, stood on top of shipping containers and crossed train tracks, nipped behind bollards to get a better look at the ornate stonework of buildings waiting to be torn down. As well as commissioned murals, there was a sprinkling of graffiti, much of which seemed to reside inside buildings only made visible when the insides became the outsides halfway through demolition, like the one on Tuam Street.

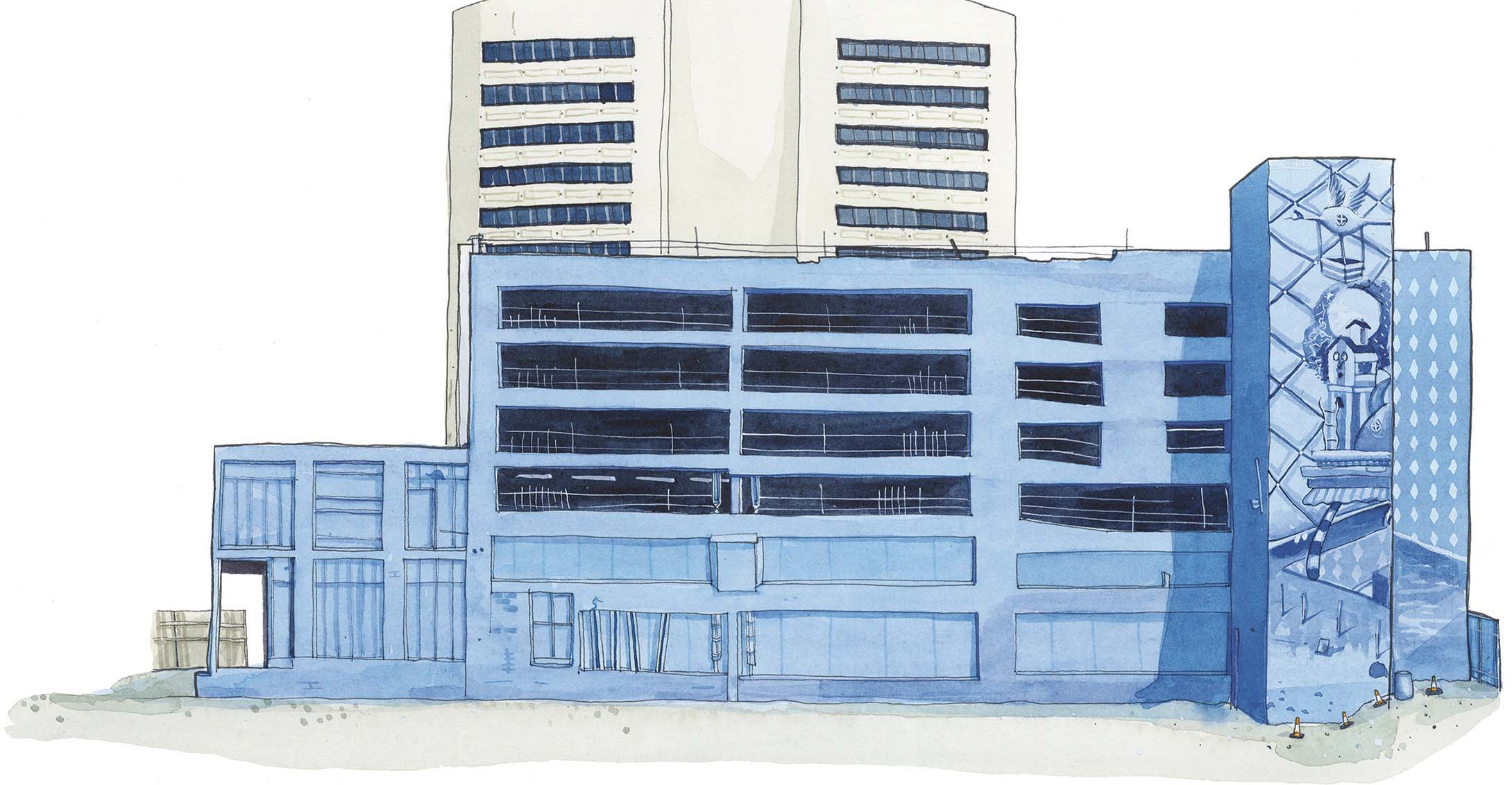

Unsurprisingly, graffiti as extreme sport was also visible on the few remaining high-rise buildings. After all, if the population is expected to thrive under the stress of imminent natural disaster, it makes sense that a percentage of those would also relish the adrenaline of scaling these abandoned buildings. I photographed reference of the Rydges hotel car park that featured a huge commissioned mural by the Christchurch artist Jacob Yikes. Directly behind it, the tag ‘TOGO’ could be seen in large painted letters on the top edge of the hotel building, painted from up on the roof whilst the building was empty. I thought about leaning over the edge of the roof far enough to paint the letters with rollers, in a city that regularly shakes and moves, and I gained a brand-new respect for the writers that dare to reach such spots.

Graffiti also found itself on the sides of shipping containers that were placed in front of unstable facades to prevent them tumbling onto pedestrians in the event of another aftershock. It was whilst I was standing on top of one of these shipping containers taking reference photographs of an elaborate wall, that a small earthquake hit. I was too busy scrambling around to notice, but others did and it became a source of conversation in places I visited later that day. Perhaps my own predilection for a little danger and excitement, for exploring places that were once inhabited, made me the perfect candidate for a life in this new Christchurch. I thought back to my neighbour on the flight in and smiled at the difference in our responses, understanding now why attracting a younger population was so important for the Christchurch that would rise up from the ashes and rubble.

Tuam Street deconstruction, Christchurch.

Shipping container walls, Christchurch. Featuring FOC, KUEO.

We Got the Sunshine by OliviaLaila and Holly Rocck, Christchurch. DEFTAG visible behind.

Rydges hotel and car park, Christchurch. Featuring mural by Jacob Yikes and heavens piece by TOGO.