Crack is Wack, Keith Haring. Harlem, New York.

New York! I’d arrived with a plan for New York. One of the birthplaces of modern graffiti, I’d made it my mission to hunt down some of the oldest pieces that still existed in the city today. This was the place where writing your own name in public turned from a strange expression and act of rebellion by a small group of friends, into a worldwide epidemic that I had been crossing oceans in search of.

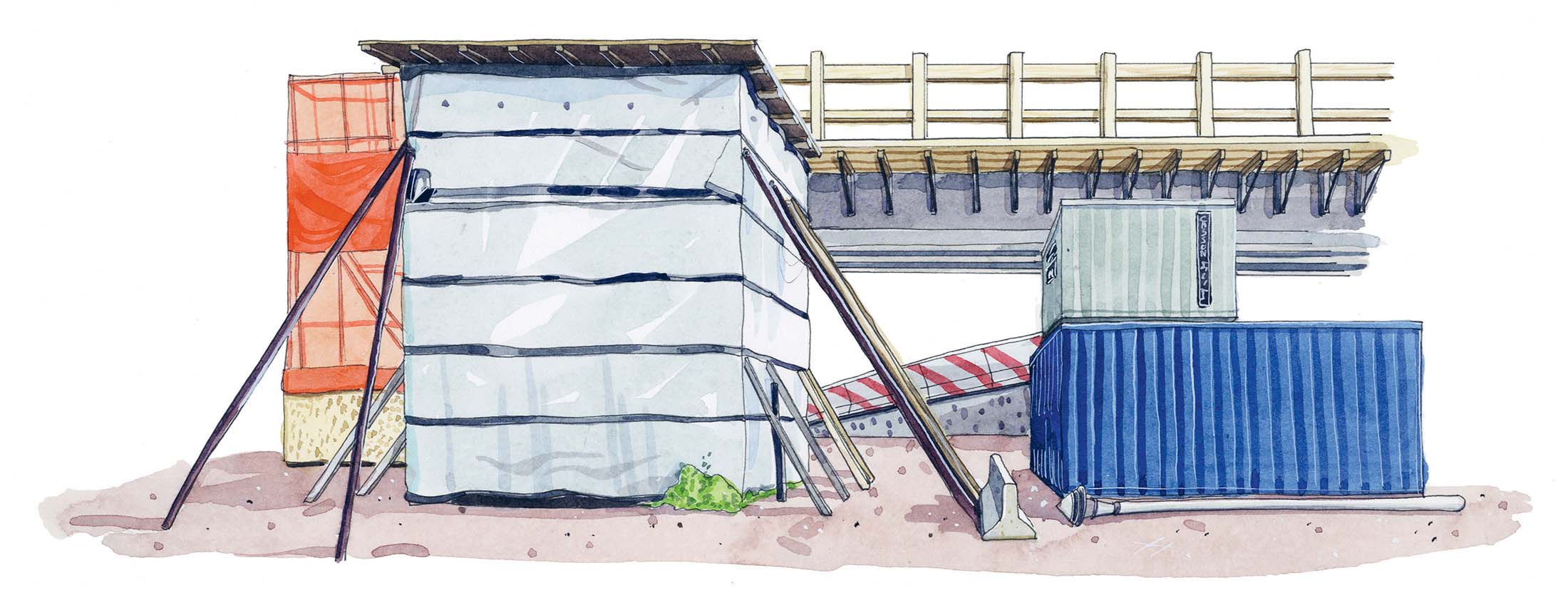

My plan ended up not quite working out the way I had hoped. I had a list of locations and spent a day turning up to spots all across Manhattan to find that the work no longer existed. The location of one piece was now just a buffed cream wall. Another had a large advertising video screen screwed in over the top of it. The city was changing so rapidly that only two of the works on my list still existed. One of these was Keith Haring’s ‘Crack is Wack’ piece. It was 32 degrees Celsius (89.6°F) in Manhattan on the day I took the subway over to Harlem to find the work. I skated along the bustling Harlem high street before pushing along the back streets for a while. I reached the handball court next to Harlem River Drive, the location from my research, to find. . . nothing. Well, yet more building work, fences, diggers and hi-vis-vested workmen. I hunted around the areas I could get to, then nipped behind the fences to have a better look. I cross-referenced old images of the piece, looking for clues in the landscape of the exact location, but the rebuilding of that part of the highway meant that nothing quite matched up.

After a while of fruitless searching there was one answer right under my nose. A large tarpaulin-covered structure may just be protecting the work from getting damaged by the construction. I found a gardener in the park beside the handball court and asked him. He confirmed it. Yes, the work was beneath the thick sheets of blue plastic.

Painted by Haring in 1986 without permission, the location next to such a busy highway and bold message would help propel Haring into becoming one of the most iconic street artists of the 1980s. He was arrested as soon as he finished painting the wall, yet the positive publicity that the mural received, at the time crack was a growing national problem, resonated with the media, and this publicity ultimately spared him from going to jail. The original painting was then vandalized a short time later, but this same positive publicity for the piece led to the Parks Department asking Haring to repaint it. The repainted version was not identical to the first but the message was still the same, and it is this version that was sitting under cover with the protection of the city three decades after his arrest. I had seen, time and time again, instances of people who pushed at the boundaries in search of artistic expression who would then be held up by the very hands that once pushed them down. Their work would be used to raise property prices and sold to art dealers.

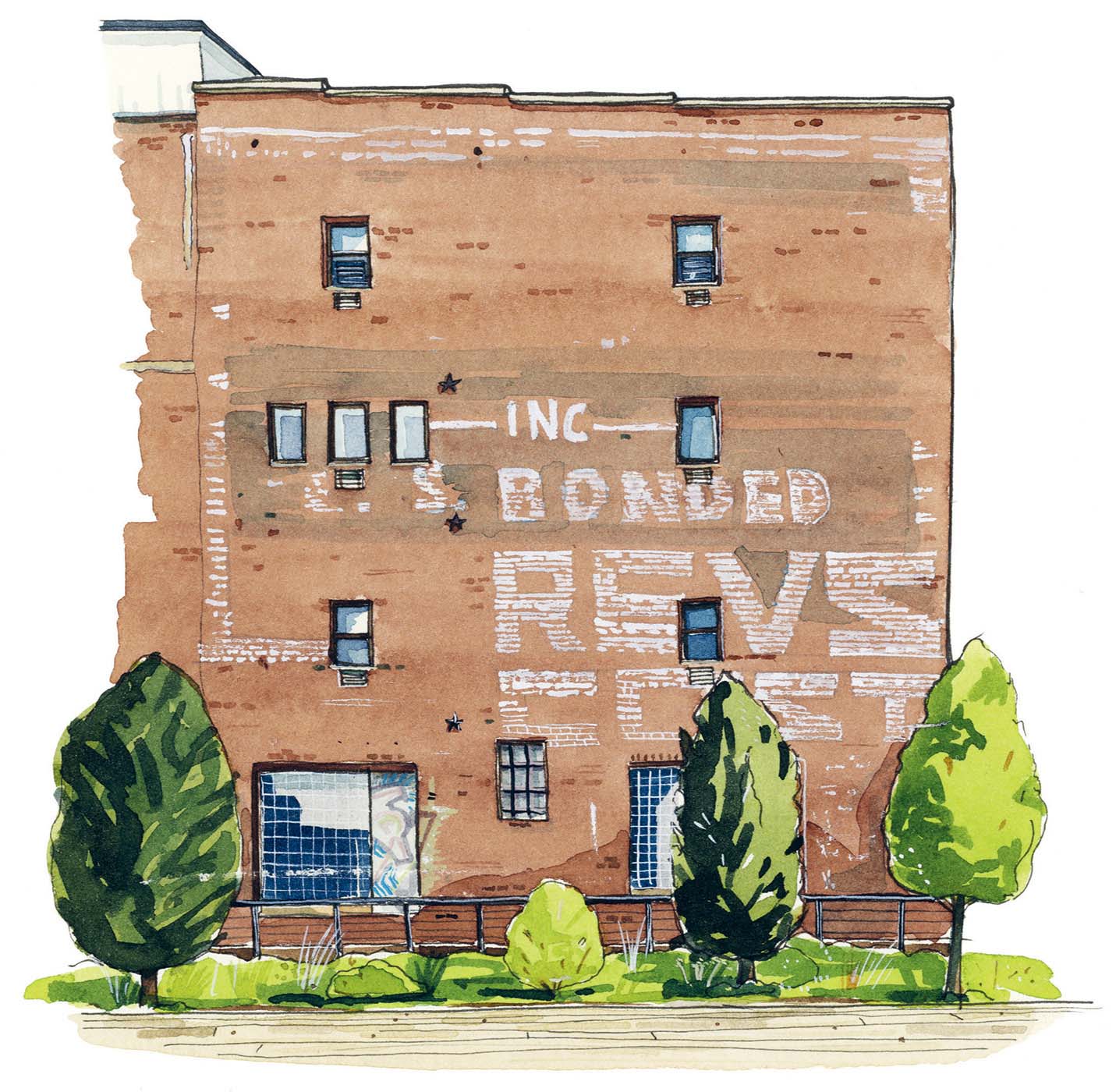

Back from my trip out to Harlem, I went on the hunt for one final historic piece of graffiti by the writers REVS and COST. Prolific and creative from the 1980s onwards, they too pushed the boundaries of what could be considered graffiti in the pursuit of ‘getting up’. ‘Getting up’ is the aim of making a name for yourself as a graffiti writer, either by spreading it through volume, scale or remarkable location. REVS and COST were some of the first to utilize paint rollers instead of spray cans so that their work could be completed at a much larger scale across Manhattan; the technique used by these artists was rejected by many at the time for not being ‘real’ graffiti, but would become adopted across the globe years later, a precursor of other methods for producing large-scale graffiti, such as the fire extinguisher work by the likes of Katsu.

Crack is Wack, Keith Haring. Harlem, New York.

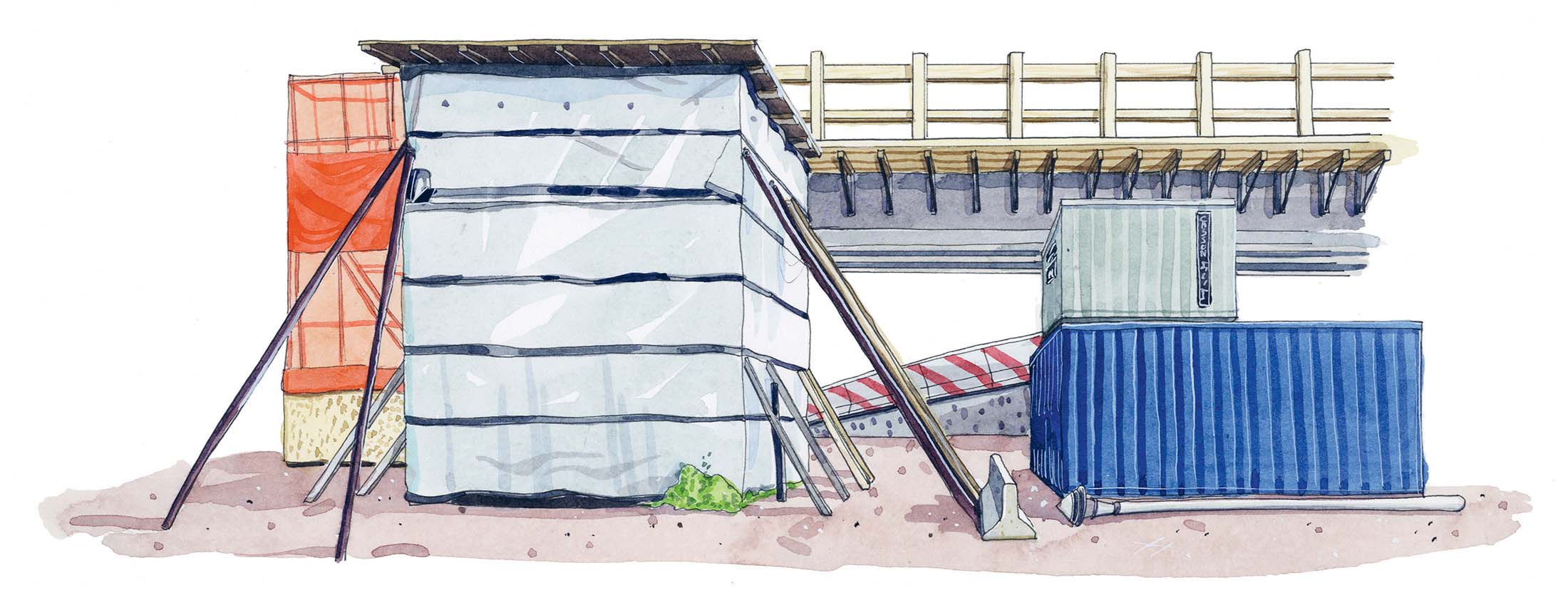

I walked the High Line looking for the piece I had heard about. After all of my disappointing searches, and the volume of high-rise building that butted right up to the above-street walkway, I was sceptical as to whether I would find what I was looking for. I stopped by a large group of tourists looking out and taking photographs of some murals on the walls opposite and hunted the brick buildings for the huge roller letters I was looking for. After a few minutes of hunting I turned around and glanced at the wall behind me – the wall that saw a thousand backs. There it was. The large paint letters were faded and flaked and unremarkable, unless you knew the story of where they were from.

In 2011, during the construction of the High Line, it was feared that the graffiti would be removed altogether. One day, workers painted over the letters with some kind of removing substance; the next day, the letters still remained but as a shadow of themselves. A ghost on the wall, faded to almost the same degree as the original painted advertising on the sides of the warehouse declaring the warehouse owners. The similarities in the text also reflected the similarities in the human urge to have one’s name known. To write it large for all to see, as if seeing it is tied into your existence.

A few days later, I travelled to an old industrial area of Brooklyn called Bushwick, one of the few parts that still contained warehouses. It was now famous for the street art and murals all over the walls that were repainted every year during a large community event with music, food and live painting. Thousands of people flocked to the area, cramming the streets. The Bushwick Collective was the group name for the work that was everywhere. I had seen many of the artists’ work in other cities around the world – artists moving from place to place, leaving their mark.

There are very few places in New York where street art is allowed, and so seeing such a large concentration all in one place made the area unique. It wasn’t long ago that there was no billboard advertising here – there weren’t enough passers-by to warrant it. Yet, as the popularity of street art rose, and the work of international muralists continued to fill the walls and draw people in, other signs of gentrification popped up – high-end coffee shops, cool bars, restaurants and advertising. There was a growing trend for large-scale, hand-painted adverts, made in such a way as to integrate them with the street art, borrowing from its visual language and incorporating the kudos of craftsmanship. My thoughts went back to the large warehouse in Manhattan with the name of the warehouse owner painted across the side. Was this just a modern version of that?

When walking around looking at the street art and murals, a graffiti writer friend pointed out that the content of the work on the walls was also heavily curated by the building owners to ensure that nothing controversial was painted. Artwashing is the term given to the gentrification acceleration technique by property owners or developers wanting to raise the value of their area by commissioning art projects and murals on their buildings, attracting a different demographic with more money to a previously overlooked neighbourhood. The rough brick walls then become shabby chic, industrial warehouses become loft apartments and landlords become rich. Whether intentional or not, the large collection of work in Bushwick has had some role in the rise in rent and business rates, driving long-term residents out from the neighbourhoods they grew up in. This idea of the gradually changing sociodemographic population of an area drew me to one particular piece of work in the centre of a construction site in the heart of Bushwick. Hanging on a large steel I-beam was the word ‘Home’, seemingly cut out of thick steel. I could not help but feel that, when the construction was over and the word no longer hung on the edge of the I-beam for all to see, this place would not be home to many who had once called it so.

REVS and COST, Highline, New York.

Handpainted billboard. Brooklyn, New York.

Near the Holland Tunnel, New Jersey. Featuring INDECLINE, buff monster, COST, Nychos, MSK.

‘Home’, Brooklyn, New York. Featuring Joeiurato x Logan Hicks and Killz Montana.