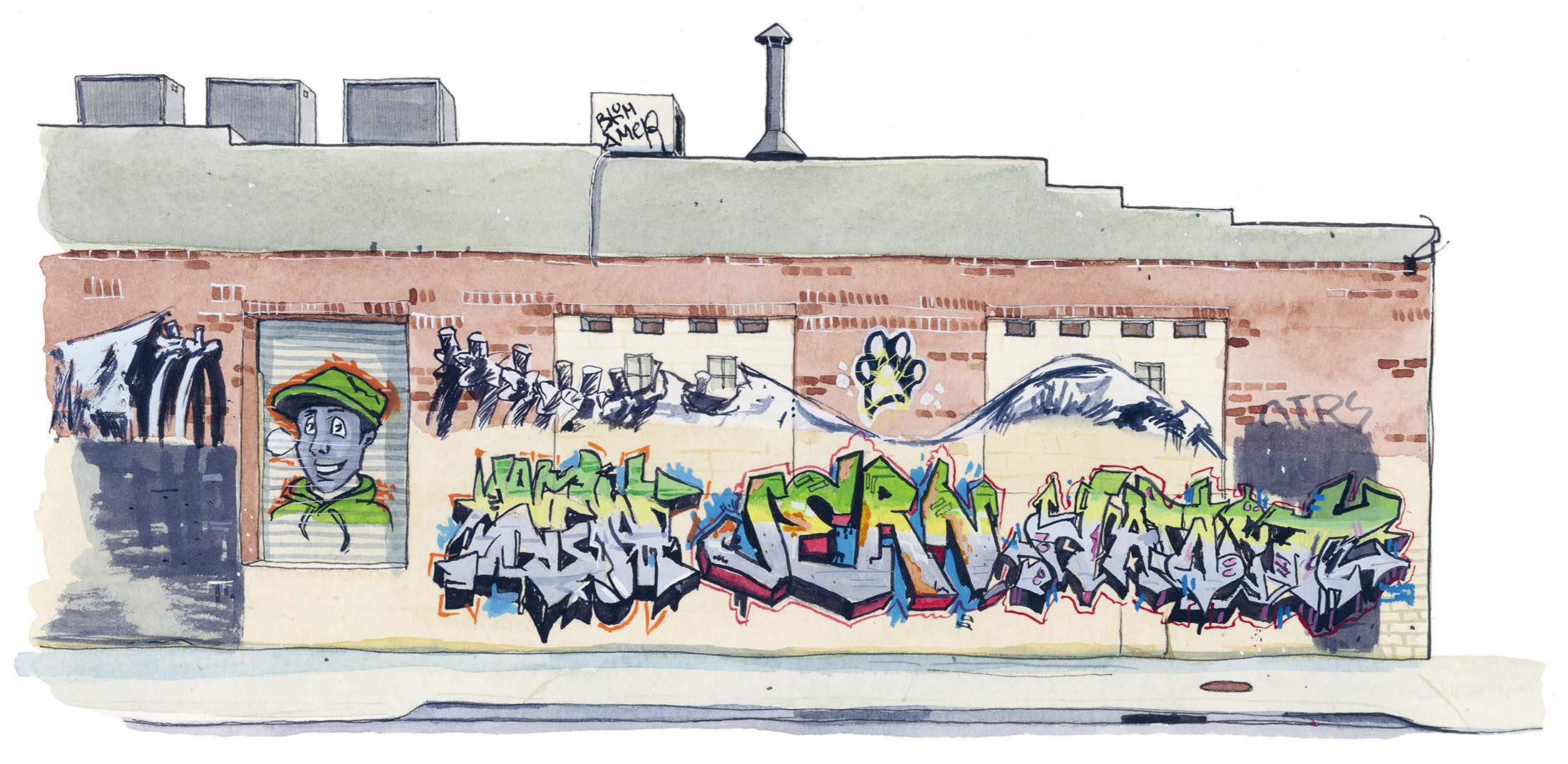

Venice Graffiti Walls, Venice, Los Angeles.

Los Angeles: a city filled with people who shared the dream of seeing their name in lights. Those who desired to be known and to stand out from the crowd were often moved by an urge so similar to what motivated many graffiti writers that the parallels were uncanny. Home to Hollywood and Sunset Boulevard and the Walk of Fame and to those who had made it, in their huge Beverly Hills mansions. Home also to the many more who were sacrificing everything in the hope of one day receiving the acclaim that they dreamed of.

Whilst New York is often given credit for the birthplace of graffiti and tagging (in the form that we know it today), it was Los Angeles where the different environmental factors played into innovating new ways of ‘getting up’. A sprawling city of freeways, the painting of graffiti on freeway signs, known as ‘heavens’, gained more attention and was a daring alternative to train bombing, the East Coast favourite for ‘getting up’. The car rather than subway culture played a large role in this difference. If the goal of successful graffiti was to get as many eyes to notice it as possible, this was a clever solution. Another element feeding into the Los Angeles style came from the Chicano gang graffiti of the Sixties and Seventies that had a carefully meticulous hand style. This played some part in writers of the Eighties and Nineties taking time over their writing, pulling in elements of calligraphy and handwriting, often elegant and comprised of a single line.

I cycled around the downtown arts district with my guide, a local graffiti writer called Carlos. Bikes were the best way to cover the large areas between the industrial buildings and to cross under the freeways whilst still allowing us to stop every hundred metres so that I could shoot reference photographs and hear stories. We passed several different people working on murals under a bridge, and Carlos stopped and chatted to them all. Cache K4P was one of them, part way through painting a new wall. I saw a slice of the community aspect of a world so often talked about in terms of being individualistic or even egocentric. We paused at the work of some of the more famous street artists and I was surprised to see the lower half covered in tags and throw-ups.

A rebellion was happening: a conflict between the street artists and graffiti writers in downtown Los Angeles. There was a rise in awareness of how turning industrial areas into open-air art galleries and tourist attractions had the effect of increased rent, and priced nearby long-term residents out of their communities. As a general trend, a lot of graffiti writers were local to the area where their work could be seen, whereas it was unusual for street artists to be located within the communities where their work was painted. I heard about neighbouring Boyle Heights, an affordable and largely Latino and Hispanic community that was earmarked for redevelopment. The backlash from anti-gentrification groups took the form of vandalism of the new businesses opening up. Controversial and desperate, but perhaps these same motivations were being seen written on the walls in the arts district. Local residents were pushing back the tide of development in any way they could; showing their displeasure at what felt like the slow invasion of their communities. My guide told me of a piece by the street artist ROA that had been tagged over, and ROA had returned to repaint it, then the repainted image had been heavily tagged over again. Other street art pieces had been tagged, but in an effort to clean up the tagging, more prominent graffiti writers then moved in and covered the tags with large skilled ‘pieces’. The respect that they carried within the community left their pieces mostly unspoiled. There was a complex conversation happening on the walls of the buildings in this area between the different communities of street artists and graffiti writers. The conversation was happening at different times, perhaps between people who would never actually meet, but the paint-covered brick and metal structures contained a palimpsest of dialogue.

Just a few days earlier, I had been sitting outside a coffee shop in Venice Beach talking to a stranger. He told me about how he moved to Venice Beach a decade ago to make a new life for himself, but the rising rents had driven him from one neighbourhood to the next, pushing him further and further away from where he worked chasing affordable rent, but he had reached the point where he was going to have to move to another city altogether. The perpetual relocating was making it harder for him to establish proper relationships with the people around him as he slowly got pushed from one place to the next.

Venice Graffiti Walls, Venice, Los Angeles.

Having seen the hollowing out of communities and areas in cities around the world due to gentrification, I had developed a new interest in the groups that were using whatever means at their disposal to hold their ground. Those that could see the trend and patterns of countless other neighbourhoods as rents increased to unaffordable levels, forcing small businesses to pack up, and residents to move to different areas.

Back in Venice Beach, right next to the world-famous Skatepark, were the Venice Art Walls. A free and legal place where anyone could paint, spray or paste, these walls had been in existence for more than fifty-five years. Originally built as the Venice Pavilion in 1961, much of the pavilion was torn down in 1999, but sections of it plus the chimneys were kept as living memorials to the graffiti and murals that had covered them for decades. The walls were now run by the Setting The Pace (STP) Foundation, a community arts organization set up in 1987 to utilize the power of art within the community for positive change – a recognition of the power of allowing people a place to express themselves, and how this could become a force for good in the world.

Looking for more ways in which graffiti had united people, I headed back to the Santa Fe area of downtown LA. The boxy shape and large size of the concrete cube architecture lent itself perfectly to huge back-to-back murals and collaborations. One of these buildings, a large plumbing warehouse in southeast downtown, would become one of the largest collaborations in the whole of Los Angeles. UTI, a graffiti crew that consisted of over 200 members and celebrated their thirtieth anniversary in 2016, pulled together to produce the work that wrapped around two sides of the huge warehouse. Thirty of the crew’s members worked tirelessly to produce the piece in time for their anniversary celebrations. Completely covered, the quality of work was exceptional, yet it was a combination of many different styles, harmoniously sewn together, allowing each individual to shine without their work becoming homogenized or replicating each other. The crew also invited Los Angeles-based street artists to contribute: El Mac, with his portrait work made from sprayed concentric circles, the intricate calligraphic work of Retna, and the graphic lines of Kofie. After seeing so much conflict playing out on the walls in the arts district, it was the perfect contrast to see how the art form could be used to unite people, to allow them to express themselves in their own unique way but be tied together to create something as a group. Like a choir singing a song, each contributor brought a different tone, making the song fuller and richer than a single voice could ever achieve.

‘Fish and Chips’, Venice, Los Angeles.

ROA, Downtown, Los Angeles.

UTI thirtieth birthday collaboration, Downtown, Los Angeles. Featuring El Mac, Retna and Kofie.

Back Alley, Downtown, Los Angeles.