Dame Emily Skatepark, Bristol. Featuring Feek and BUZZ.

‘Why Bristol?’ was the question running through my mind as my train hurtled through the English countryside from London. What made this city of fewer than 500,000 people a hotspot of urban art? It was founded on its harbour, shipping and the slave trade, but its modern economy is comprised of the creative industries, electronics, aerospace, and its two universities. Home to the early works of Banksy, arguably one of the most famous contemporary urban artists in the world, Bristol is also the location of Upfest, an annual street art festival, the largest of its kind in Europe. But what was the catalyst for its unique and often political street art scene? What did Bristol have that other places did not?

I skated the streets of the city looking for clues. It was densely populated and topographically hilly, with diverse architecture that had been constructed through the centuries: a medieval castle, fancy Georgian terraces built from the profits of slavery, Brutalism and extensive rebuilding in the later twentieth century due to the heavy bombing during the Second World War.

What immediately seemed odd as I pushed around the city, was how the street art was not primarily located in the industrial areas or alleyways like so many other cities around the world. Much of it was on the sides of regular houses or on the back-to-back coverings of shops on the high street. The street art was not hidden away but there for everyone to see as they went about their daily lives.

I had arrived in town just after the Upfest Festival had finished, evidence of the 2017 event painted all over the walls of North Street and the surrounding residential areas. A brand-new Buff Monster piece, ‘Something Melty This Way Comes’, covered both edges of the Salvation Army community shop on East Street with bright coloured paint. However, I was in time for Dean Lane Hardcore Fun Day, or Deaner Day as it is known locally. This is an annual skateboarding event with music, food and graffiti at the rough and wild skatepark in Dame Emily Park. Held in its current form since 1999, with similar events at the park that could be traced back to the 1980s, it is one of several long-standing community traditions that marked Bristol out from other places. Started by Dylan Lewis and a hardcore group of skaters as an alternative to mainstream skateboarding, holding on to their punk and hardcore music roots, the event was left alone by the police and so the group kept up the tradition. I made myself useful, buffing the surfaces of the ramps in the Dean Lane skatepark ready for fresh graffiti to be sprayed ahead of the Saturday extravaganza. It felt good to be involved in the work for a change, rather than just being an observer. I had forgotten how great it was to feel a part of building something with a group of people. This feeling of creating with others was much more satisfying than just consuming with them.

And what made the city special was the story of the people. Bristol still maintained a thriving underground music and art culture – communities that did not wait for things to happen to them, but rather made things happen, year after year. People who were prepared to put the work into events that celebrated the values that were important to them, not for fame or fortune or worldwide recognition, but to work for the sake of creating something. Music, skateboarding, graffiti and beer.

The fact that I knew so little about Bristol as a city before I arrived highlighted to me that it was its own little microcosm, and this gave people a greater freedom to create what they wanted without much interference from outside. It was also a city that held on tightly to the practical realities of sustaining community. The power of people working together also gave them greater power than people working as individuals – groups of like-minded people are harder to control.

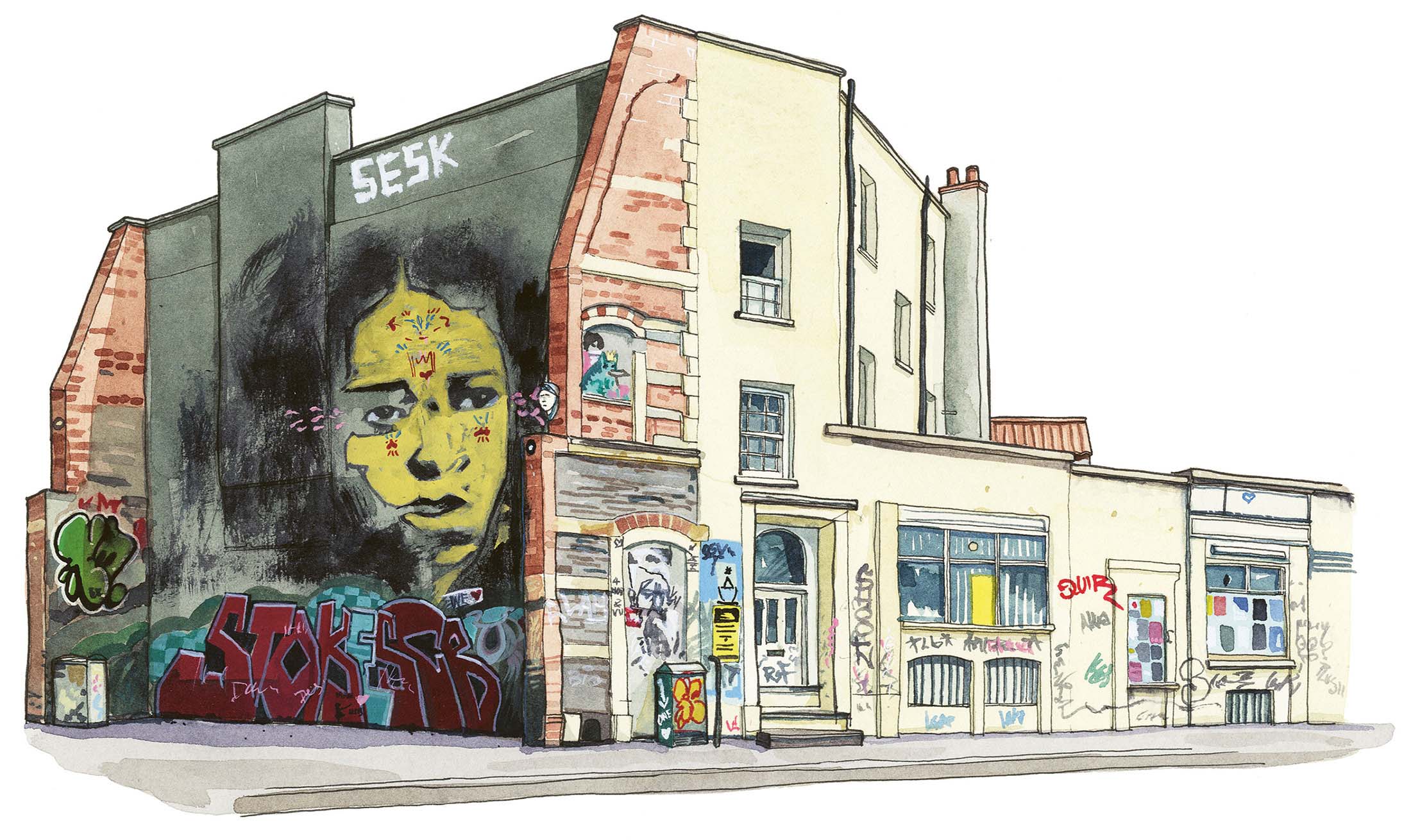

I had heard that the beating heart of the politically active community of Bristol could be found in the Stokes Croft area. Greeted by the huge yellow stencilled face by Columbian artist Stinkfish, painted in 2012, I walked the brightly painted streets. Here, ideas were expressed on the walls without the space to breathe like in other parts of town. The graffiti and street art was layered and mixed together, confusing and loud, like a community meeting where everyone talked over each other because everyone’s voice was equally valid. At first glance it was chaotic, but also beautifully democratic and important. Whilst in the area I dropped into Stokes Croft China, a shop run by the People’s Republic of Stokes Croft (PRSC), where I talked at length to Chris Chalkley, the Chairman of the PRSC, about how important graffiti and art was to political activity in the city. The vision statement of the PRSC had a strong emphasis on expressing ideas as a step towards making them a reality; using public art as a way of raising awareness of the things that mattered both within the community and looking out to the world as a whole. Their aim was to constantly and relentlessly question the status quo as a means of improving society. Founded in 2006 when graffiti was being painted stealthily at night and then buffed grey by the council very shortly afterwards, the PRSC worked hard to make public art accepted as a democratic creative expression that should be allowed to thrive. The painting of the Welcome To Stokes Croft mural resulted in the painters being arrested and taken to court. As a result of this incident, there was a U-turn in the response from the authorities to illegal painting on the walls of Stokes Croft. Following this change, the streets slowly filled up with colour.

Dame Emily Skatepark, Bristol. Featuring Feek and BUZZ.

Girl with the Pierced Eardrum. Banksy, Bristol.

Of course, I couldn’t go on a street art hunt around Bristol without acknowledging Banksy. The first-known large-scale mural by the artist being the ‘Mild Mild West’ piece in Stokes Croft in 1999, it is believed that Banksy was a product of Bristol’s thriving underground arts and culture scene of the 1990s. Banksy is now recognized as – rather ironically given their anonymity – one of the most famous street artists in the world. Their work is a notable catalyst in the shift of how street art has been perceived by the art world over the last decade. I went to find the piece ‘The Girl with the Pierced Eardrum’ (a parody of ‘The Girl with the Pearl Earring’ by the painter Vermeer), which was located behind Dockside Studios, a local recording studio, surrounded by industrial buildings. It wasn’t the kind of place you just stumble upon whilst taking a leisurely walk around town. As I stood nearby, a number of people came to photograph the piece – many of whom were smartly dressed, travelling in pairs, often middle-aged. A testament to Banksy’s ability to appeal to a demographic beyond their peers. In fact, it could be for this reason that ‘The Girl with the Pierced Eardrum’ was splashed with black paint just twenty-four hours after completion.

Regardless of its popular appeal, Banksy’s work is humorous, satirical, political and often has anti-establishment themes that connect with people. Visual epigrams expressed through stencilled paint on walls.

Friends who lived in the city joked to me that they wanted to build a wall to stop more people with average ideas coming in and spoiling their lovely multicultural and vibrant home, watering it down with their unquestioning minds. This idea of keeping it all in brought me back to thoughts of why I had little knowledge of Bristol’s unique microcosm before I arrived. So many inspiring things thrived there that never left the city boundaries. People elsewhere didn’t know what they were missing out on. Banksy’s work took a small part of this out into the world and it resonated with people. It left the city and took a part of the heart of it out into the world, showing the power of ideas expressed on walls to change not only the art world but to shine a light upon the people and communities creating street art. It had elevated the status of street art to something that should be taken seriously, not just a frivolous thing, not just selfish vandalism or ‘me, me, me’, but rather a reflection of the people and societies making it.

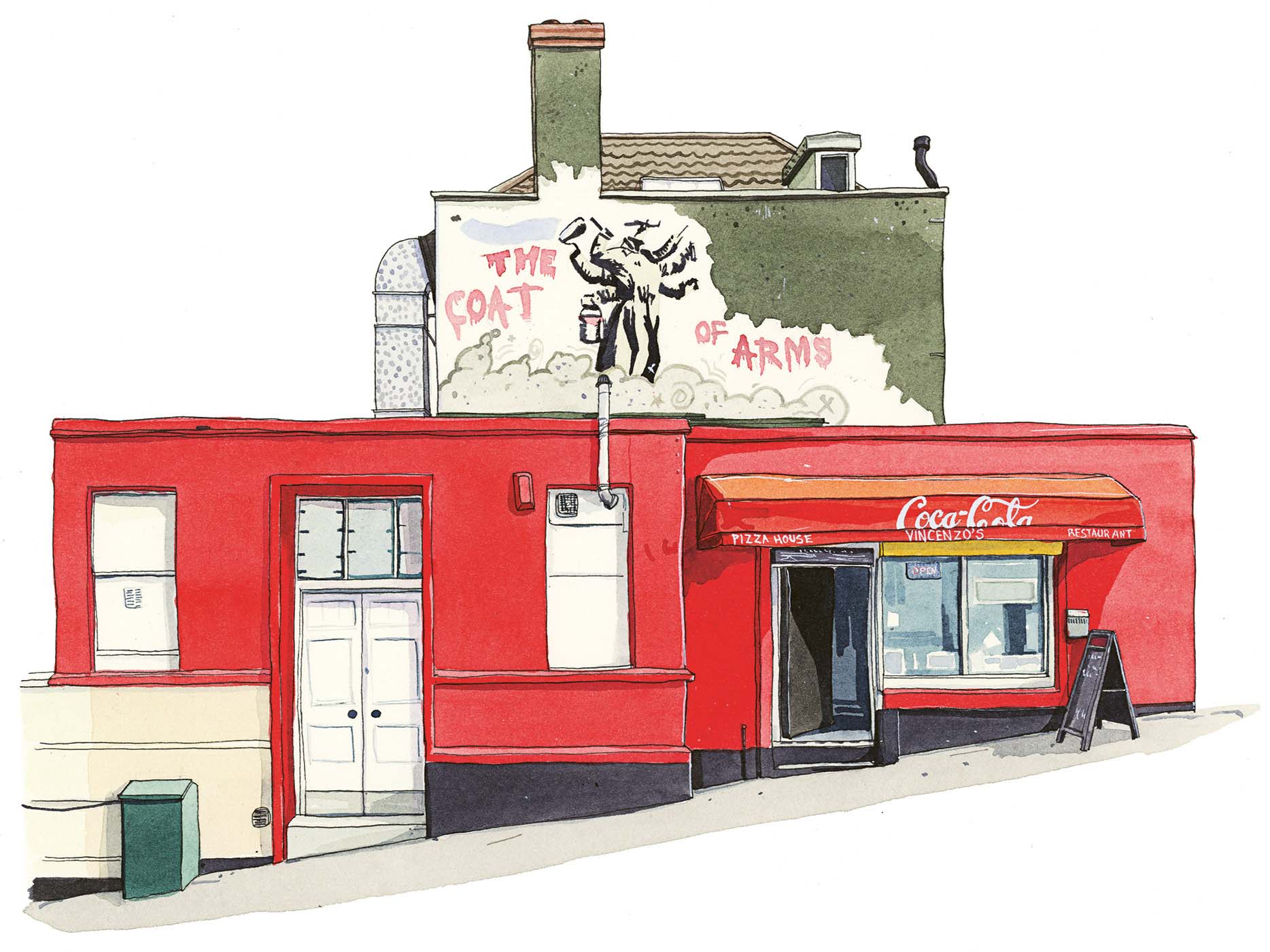

Coat of Arms. Nick Walker, Bristol.

‘Face’ by Stinkfish. Stokes Croft, Bristol.

Buff Monster, Church Road, Bristol.