Phoenix Commotion Basics

Phoenix Commotion BasicsCHAPTER 7

A TALL ORDER

IN TEXAS

The Phoenix Commotion’s unique, artistic homes

keep waste out of the landfill and communities alive

in Huntsville, Texas.

IN 1998 IN HUNTSVILLE, TEXAS, Dan and Marsha Phillips founded the Phoenix Commotion, a home-building business dedicated to providing low-income housing for working folks — mainly single-parent, and low-income families and working artists. The company keeps costs low by building with salvaged materials collected from all over the world. Made from an unusual and diverse assortment of building materials — landfill-bound scrap wood and insulation, used wine corks, adobe, stone, bottle caps, shards of broken tiles and mirrors, papier mâché, old plates and CDs, to name a few — Phoenix Commotion homes don’t look like the standard suburban ranch house. These homes, part perfectly personalized living space, part living art project, look more like something dreamed up in a fairy tale than something you’d find in a subdivision. As Dan Phillips explains, a town the size of Huntsville throws away enough waste to build a small house every week. He’s trying to build those small houses.

Phoenix Commotion Basics

Phoenix Commotion Basics

Dan Phillips has had several careers throughout his life, and today he applies skills from all of them to his dream job. Spending ten years as a dance professor at Hunstville’s Sam Houston State University (SHSU) gave him skills in instruction and artistry. Long dedicated to the idea of creative reuse and making new from old, Dan and his wife, Marsha, opened an art and antique restoration business called the Phoenix Workshop in 1985. The store gave him the chance to see all the great “waste” materials coming out of the construction industry in his area. But it wasn’t until 1998, after 35 years of marriage, that they decided to make good on Dan’s lifelong dream of becoming a builder. They mortgaged their home and founded the Phoenix Commotion, Dan’s salvaged-home-building business. By 2003, the Phoenix Commotion had taken off to such a degree that Dan could no longer split his efforts between the Phoenix Workshop and the Phoenix Commotion, so Dan and Marsha closed the Workshop to focus full-time on the Phoenix Commotion.

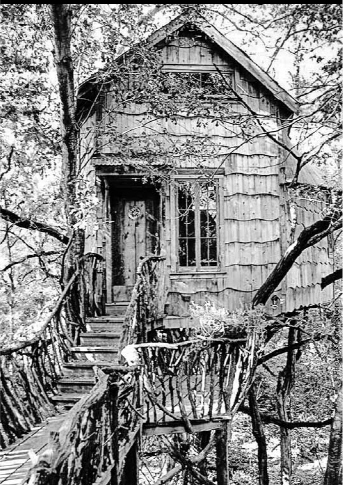

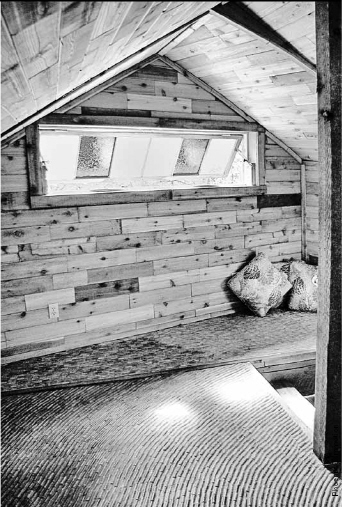

One of Phoenix Commotion's many unique designs, "The Treehouse" is made of reclaimed lumber.

Named for the mythical phoenix, which continually renews itself from its own ashes, the Phoenix Commotion makes its business out of using resources others consider worthless. Dan builds affordable homes with salvaged, slightly damaged and other unwanted building supplies he obtains for free from manufacturers and wholesalers. He is driven by a twofold commitment: to keep usable building materials out of the landfill and to provide homes for the working poor. The first, he says, was borne of a childhood with parents — a lumberyard-working father and homemaker mother — who had lived through the Great Depression. “We never threw anything away,” Dan recalls. As a child, he would go to landfills with his parents and search out usable materials. He built his first bicycle at age 14 from parts he found there. He says his fascination with saving old things from their landfill fate found a perfect match when he realized the great need for affordable housing in his area: “I had always suspected that one could build an entire house from what went into the landfill, and, sure enough, it’s true. Then, with the crushing need for affordable housing, [building homes] was a natural connection.”

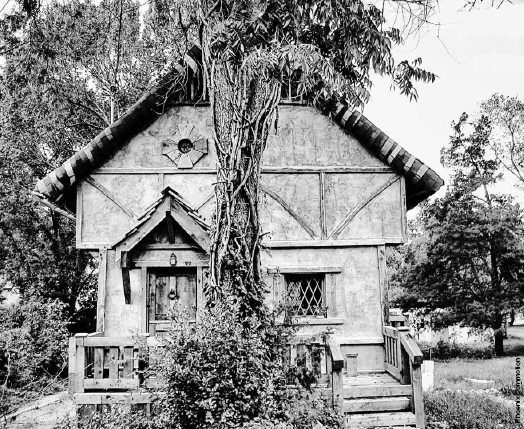

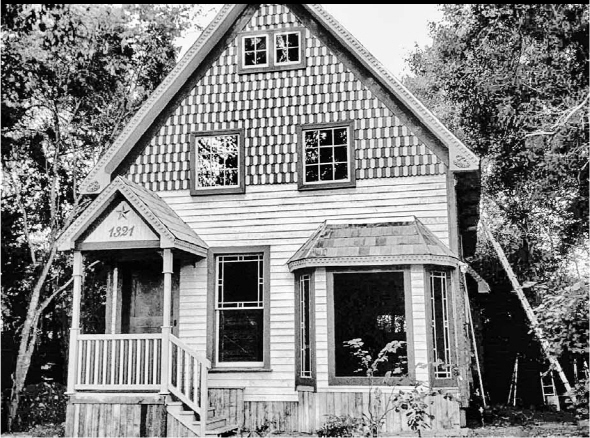

The “Storybook House” is one of dozens of Phoenix Commotion homes that are taking over whole sections of the city.

Along with keeping building supplies out of the landfill, using free materials helps Dan achieve affordability. So does his crew. Every Phoenix Commotion project is manned by a staff of untrained minimum-wage builders, community volunteers and the homes’ future owners, all under Dan’s expert tutelage. Of his crew, Dan says the building program is part job, part apprenticeship: “I only hire unskilled workers at minimum wage, but they get a fire-hose of information and training during their tenure on the crew. When they have enough skill to compete in the marketplace, I push them out the door when permanent jobs become available at a higher rate.” Each untrained, paid crew is occasionally supplemented with a slew of volunteers from the community and SHSU. The final crucial component of Dan’s workforce is the future homeowner — he requires every homeowner to participate in the building of her home.

Building a Phoenix Commotion Home

Building a Phoenix Commotion Home

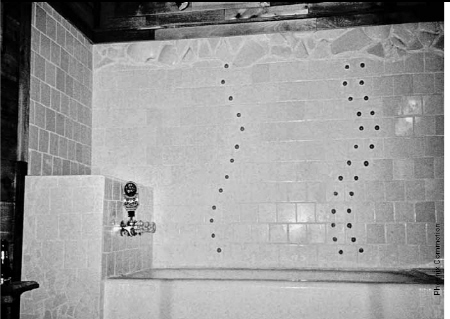

The first Phoenix Commotion house was a Victorian-style charmer constructed over 18 months beginning in 1998. The exterior walls contain no studs; rather, they are made of blocks of western red cedar that Dan and his crew stacked, glued and toe-nailed together. Victorian houses often have turrets — small ornamental towers on the front of the home. The Phoenix Commotion Victorian is no different, except that its turret is constructed of stacked, nailed and glued nine-inch chunks of western red cedar 2-by-4s. In an artistic unification of indoors and out, Dan constructed a high-backed master bathtub using the same method. Hickory nuts and egg shells filled with Bondo provide decorative accents on the outside of the house — a homespun alternative to marketed counterparts.

The two main tenets of a Phoenix Commotion home are reuse and efficiency. By gathering materials from all over the world, the company provides a valuable service to its building-supply donors: a guilt-free, non-landfill destination for post-market building materials. Word of the Phoenix Commotion has gotten out to everyone from local businesses to large national ones such as Weyerhaeuser and McCoy’s building supply companies. Rather than pay a hefty fee to send their leftover supplies to the landfill, companies ship materials to Dan’s warehouse, providing tons of valuable lumber and supplies for free. Because scavenging is banned at Texas landfills, the key is getting access to landfill-bound supplies before they’re sent there, Dan explains: “I go to wholesalers, and the scenario is this: The wholesaler will sell 75,000 square feet of tile, and then the person who bought it says, ‘I really only need 72,000 square feet.’ The wholesaler says, ‘OK, fine,’ and they end up with the extra 3,000 square feet, which isn’t enough to sell at a wholesale level and ends up at the back of a warehouse. Eventually they say, ‘Let’s get rid of this stuff. Let’s give it to Dan.’”

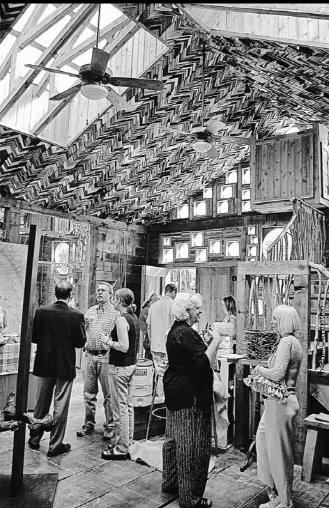

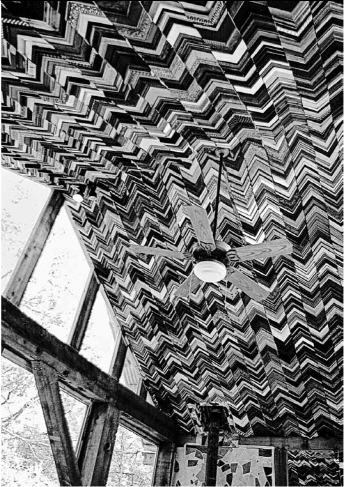

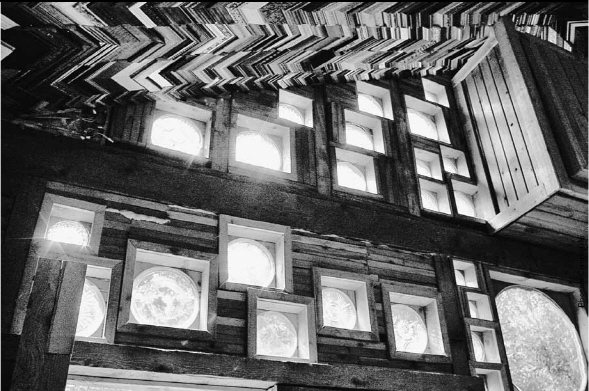

Inside the “Treehouse Studio,” frame corner samples from a photography framing store combine to create a zigzag-pattern ceiling.

Because wholesalers must pay a fee to ship materials to the landfill, sending it to the Phoenix Commotion saves them money. The donation is also tax-deductible, making it extremely financially attractive to wholesalers. After a few years of doing this work, Dan says that he rarely finds himself in short supply: “Over the years, the companies know what I’m doing, and they ship it to me. One afternoon, I’ll receive an 18-wheeler with $50,000 worth of stuff. Last fall, I got an 18-wheeler of redwood. Two months ago, I got three 18-wheeler-loads of framing lumber — 2-by-6s to 2-by-12s. They say, ‘It got a little gray on the end, let’s give it to the Dan.’” He estimates getting at least three phone calls weekly with offers of free supplies. “My advice to anyone who wants to take this on: First get a warehouse, then start sniffing around. It’ll come by the 18-wheeler.”

Without a program like the Phoenix Commotion, companies have literally no non-landfill options for efficient disposal of excess or slightly damaged materials. Wholesalers could theoretically sell them online or to private buyers, but the economic payoff doesn’t justify the man-hours required to sell small quantities; they simply won’t do it. With no infrastructure in place to reuse these materials, the wholesalers’ and manufacturers’ options are limited:

Dump it in the landfill, which is wasteful and expensive, or store it, which takes up too much valuable space. The Phoenix Commotion provides a better option.

Dan doesn’t discriminate when it comes to the types of donated materials he’ll take. He says he’s often not sure how he’ll use the offered materials, but he’s open to almost every opportunity: “My friend said, ‘I’ve got a bushel of eyeglass lenses, do you want them? What are you going to do with those?’ Well, I don’t know, but when you need hundreds of eyeglass lenses, you don’t just go out and buy them. The university gave me 15,000 DVDs. Someone offered me a 55-gallon drum of rubber bands once a week. What do you do with that? There’s no way to know. But when these things pop up, you say, ‘Oh, that’s fun, let’s try that. These things arrive, and it’s as varied as you can possibly imagine.”

One of Dan’s design tips is to go for repetition; once you have repetition, you can create a pattern, and once you have a pattern, you have a design.

Dan says the key to creative reuse is the ability to make patterns. Once you have a large quantity of any item, you can make a pattern. Patterns lead to design. He feels that, when put to the task, nearly anyone can do this: “If you have multiples of anything, you have the possibility of repetition. Repetition creates pattern and also unity. Put anyone in a room with a pile of similar objects and say, ‘I want a pattern by 3 p.m. or no dinner.’ Anyone would come up with a design. It is easy, fun and available to anybody. Most people just don’t have the nerve.”

Conceiving of how to use all these crazy materials is one of Dan’s gifts, according to former intern Jerrod Sterrett, who was nearly finished his builder’s degree from SHSC when he interned with Phoenix Commotion. He says the experience taught him aspects of building he didn’t learn in the classroom: “I learned more about art than I did about building houses. Dan is a genius in ways people don’t really even realize. If you gave most people a bunch of stuff and said, ‘Build a floor with it,’ they might be able to do it. But he can do things with stuff that gives it this very artistic feel, brings it all together and makes it look like it’s not a house made of stuff nobody wanted.”

And though he admits his homes are unique in part because of the artistry he and his crew put into them, Dan also credits much of his homes’ beauty to the quality of the reclaimed materials he receives: “A lot of these materials are things even the beautiful people can’t afford. They’re granite, travertine, vitrified china — wonderful, wonderful things!”

The round windows in the Treehouse’s front wall are made of old relish serving plates.

The fun of using unique materials aside, Phoenix Commotion homes also must go through the rigmarole inherent in any building project: efficiency, safety and building codes. Dan is serious when it comes to his homes’ efficiency. Low-cost maintenance is a crucial component of making these homes affordable for the Phoenix Commotion’s low-income demographic. High levels of insulation, efficient fixtures and appliances and built-in conservation methods make these reused homes run like brand new ones. Some materials weren’t meant to be salvaged. “I don’t hesitate to buy new,” Dan says. “Most of the time I don’t have to, but some things I buy new as a matter of policy. I buy new wire because you can’t depend on salvaged wire. I buy new pipes for the plumbing, new nails, new screws. Typically I buy new toilets because the salvaged ones I get are the 3-gallon flushers and we’re in the world of 1.6-gallon.”

A stickler for building codes, Dan states, “You have to build to code. You must pass muster and pass inspection.” He bristles at the idea that his homes, or any, should be immune to safety regulations. “Building codes are a good thing. People who throw rocks at inspectors are being naïve. It’s a lot like police officers; we want them around unless they stop us for a ticket. It’s the same with inspectors.” Meeting code doesn’t tie one’s hands when it comes to building materials and techniques, he explains, “Every building code has as a provision that alternative materials and strategies are allowed, provided you fulfill the intent of the code.”

Dan encourages his crew and the homeowners to create unique designs with the reclaimed materials they’ve collected.

Dan’s unique homes have garnered interest far outside Texas. “We Americans may have invented excess, but the problem of waste is worldwide,” Dan says. “I hear from people all over the world asking how to start something like this. I’ve been featured in magazines in Italy, in Tokyo. I think, Lordy mercy, this is a model whose time has come. I’m not starting anything new. People have been doing this for years — build with what you have.”

Financing the Home

Financing the Home

When building homes for very low-income people, financing is always a central issue. Dan Phillips has worked hard to figure out ways to get people into homes without the initial aid of a conventional mortgage. Using the same ingenuity he uses to secure building materials from a variety of sources, he has found a number of ways to finance his projects. One, a partnership with a local outreach program for women in transition, called Brigid’s Place, began offering seed money to women building their own homes. Dan has developed a similar program with Living Paradigm, a non-profit in Houston. Living Paradigm maintains the Phoenix Fund, a seed money program that gives future homeowners the money to buy supplies and get started on their home’s construction. Because the homes are built so inexpensively and with almost entirely free materials, their value as finished homes is much more than the amount of money they cost to build. Dan says that, by the time the home is built, the homeowner already owns about 80 percent of it outright. Then they seek a conventional mortgage for the remaining 20 percent. He accepts future homeowners with no credit or good credit, but not bad credit.

Dan has worked out alternatives to conventional financing, because, for homeowners with no credit, securing conventional financing is tricky. “If you walk in to meet with a banker and say, ‘I’ve got a great idea to build a house out of trash for people who haven’t shown any responsibility,’ they’re going to say, ‘Security, escort this man out,’” Dan explains. “Early out, I had to provide my own collateral,” he adds. He’s also obtained seed money for projects from private donors. “We’ve gone to private lenders. A lot of folks can come up with $20,000 and that’s all it takes to build a small house. I’ve had people step up and do that for someone.” He envisions communities coming together to create $50,000 rollover funds that pay to start projects, then get paid back by a small mortgage, then fund the completion of more new projects.

Of course, obtaining a plot of land is a key factor for any project. The price of land is one of the major expenses for a potential homeowner, and one of few that is not very negotiable. “Property is always an issue,” Dan admits. “You have to buy the property. Once in a while, someone has a lot, but not normally. Generally, you buy property at market rates where you live then what keeps the cost down in the world of Dan is a low-cost labor force and mostly free materials.”

The Phoenix Commotion Builders’ School

The Phoenix Commotion Builders’ School

Part of the way Phoenix Commotion homes stay cheap is through the extremely inexpensive labor performed by a mainly untrained staff. The Phoenix Commotion employs from two to seven workers who work under Dan’s skillful tutelage. Dan explains how Phoenix Commotion operates democratically: “Everyone does everything — from junk work to design responsibilities. No one is immune from doing the junky stuff, including myself.” The low labor costs enable him to target his desired demographic of low-income, often single-parent, families and working artists. And hiring untrained builders enables Dan to further benefit his community by providing on-the-job training for in-need Huntsville residents. Though he employs only a small number of employees at a time, the low pay ensures his apprentices are motivated to move on to higher-paying jobs after they’ve learned their craft. This means Dan leads a rotating crew of untrained workers who leave the program with a valuable skill set and who are instilled with the Phoenix Commotion message of creative reuse and unconventional building methods.

Wood log “disks” laid in concrete create a gorgeous countertop.

Homeowner and Phoenix Commotion administrative director Kristie Stevens remodeled her own home with Dan in 2008 — a house built previously for another single mother. She says Dan’s decade as a dance professor at SHSC is evident in his ease in teaching unfamiliar skills. “Learning how to use all the tools was really empowering,” Kristie says. “The way Dan teaches you to do something is by teaching you the most difficult thing first. When he taught me to cut tile on a tile saw, first he taught me to do a circle, which is kind of complicated. You have to make all these small cuts. Once you’ve done a circle, it’s really easy to do a straight line. He’ll teach you the hardest part first, so the rest is easy.”

Phoenix Commotion doesn’t have a tough time finding low-income trainees. Often, they seek Dan out; the program seems to attract them, he says: “They just wander up on the job site. Right now I have a great labor crew. I mean, my, oh, my, they’re bright, quick studies. I attract artists a lot.” He also doesn’t hesitate to reach out to those in need: “I’ll see someone who looks down on their luck and say, ‘Hey buddy, looks like you need a job. Do you have any issues with drugs, alcohol or the law? No? Then let me teach you.” His requirements are few, but vital: “You can’t have an attitude, you have to have a work ethic, and you’ve got to be interested in learning.”

Dan seeks to instill confidence in his trainees, both volunteers and homeowners, a goal he accomplishes with plain success, as is evident in talking to any of his current or past employees. “Anyone can build. It’s all simple,” says Phoenix Commotion employee and former volunteer Matt Gifford. He became a Phoenix Commotion intern after hearing about the program while attending the University of Kansas in Lawrence. He says he was fascinated, and headed down to Texas to learn more. Matt quickly adopted Dan’s can-do attitude. “People always come in and see a mosaic or something and say, ‘Hey, would you come to my house and do this?’ And we say, ‘No, but better yet, we’ll show you how,’” he says. “Anyone can glue mosaic. It doesn’t take a special skill set to glue stuff. It’s all so simple once you understand the basic concepts of a house and how it works. He suggests that, even if you hire a professional for certain more-intricate parts of a project, you can still do the majority of the building work yourself. “You can’t just jump in and do all the more complex stuff, like all the wiring, for example. For that stuff, it’s good to have a licensed person, but anything else — floor covering, ceiling covering, wall raising — if you have a back, you can make it work.”

.

Dan says people send him wine corks from all over the world, with notes inquiring, “Do you need me to drink more?”

Dan expresses his message of self-sufficiency succinctly: “I’m not throwing rocks at builders, but there’s not a whole lot to know. Gravity always pulls down. Water runs downhill. If you understand a few basic concepts, you can build a house.” For him, the training process is straightforward. “If I say, ‘Do this with the saw blade. Do it 35 times, and I’ll be back at 3:00.’ When I come back at 3:00, you’ve got that skill. It’s that simple.” Humility also has a role in Dan’s training process. He points out that he was not born with inherent abilities in building — and if he can do it, anyone can: “Nobody is born knowing how to build a house, but you can learn. Anybody can spit on his hands and figure it out.”

Though he doesn’t think building skills are hard to learn, Dan recognizes that building a home isn’t everyone’s idea of a walk in the park. Building a house is hard work. But that hard work has a huge payoff. “I’m not trying to oversimplify the process,” he says. “It’s complicated, messy, dirty, discouraging. But you can live through all that, and look what you get! You get a house.”

Phoenix Commotion homes are about as personalized as they come; the Budweiser House is modeled after the classic beer company’s designs.

Improving Lives: The Phoenix Commotion Homeowner

Improving Lives: The Phoenix Commotion Homeowner

Every future Phoenix Commotion homeowner is required to participate in the building of her own home. Dan insists upon this practice for several reasons: It intimately connects the homeowner with his dwelling; and it guarantees that the home is customized to its end user from the ground up. He also thinks that when someone works hard for something, it increases its perceived value. Though he believes everyone ought to have the right to work toward a high-quality home, he doesn’t think it should be handed to them: “I don’t believe people ought to be just given a house. I think they ought to earn it. That’s what human beings have done for hundreds of thousands of years.” Plus, by participating in building the home, the homeowner knows everything from how her insulation was installed to who delivered the 10,000 frame samples that make up the ceiling.

Kristie Stevens says that building a Phoenix Commotion home improved her life in fundamental ways: “I have two children, and I’m a single parent. It’s been a huge deal to have an affordable house payment. My kids have their own rooms and their own bathroom. I have a cute little porch.” She was able to design her home to suit her life: A busy working mother and student, she wanted something small and manageable, but she also wanted her children to have space they could call their own.

Getting involved from the ground up makes for a strong connection between home and resident. It allows homeowners to know their home on a more intimate level than if they move in after it’s already built. “You know every nook and cranny,” Matt Gifford explains. “Instead of being in this foreign space you inhabit, where you move into a place and only make it your own by putting your stuff on the wall, it’s really yours. And you really understand it and you really appreciate it. It’s a very intimate thing.

Dan encourages homeowners not only to build their homes, but to personalize them, to connect with them artistically and to use their creativity. Kristie made a giant mirror mosaic in her bathroom. She describes it with enthusiasm: “I did this big half-circle out of mirror, and then there are rays coming out of it. If you walk into my bathroom, above my sink, it looks like this big sunshine with eyes. It’s four or five feet across. It pretty much takes up the whole entire wall, but I still want to add some of the same tiles that are on my floor and work them into the sun. It’s one of my many projects. When you own your house, you’re never totally done. Especially when you know how to do all these different things!”

The bathtub in the Bud-weiser House is made with a mosaic of scrap tiles designed to look like a frothy mug of beer. The faucet is a reclaimed Bud tap.

Intimately designed by and for its unique residents, Phoenix Commotion hand-built homes harken to a time when our dwellings were intimately connected with and reflective of our lives. These distinctly personal homes are not designed for resale 20 years down the road. They are designed as lifelong dwellings. Knowing every construction detail comes in handy if homeowners want to add on to or renovate as family circumstances change. “That’s how housing used to work,” Matt says. “You’d get married and you’d build a one-or two-room cabin. Then if your wife gets pregnant, you have nine months to build a room for the baby. It reflects your life, and it’s a story of you instead of just being a suburban dwelling you get dropped into.”

Having hands-on knowledge of one’s own home comes in handy whether a renovation is in the works or not. Kristie is empowered by understanding her dwelling, plus she says she saves money on repairs: “If something goes wrong with my house, I try to figure it out or call a friend instead of calling a maintenance guy. It’s really great. Even if I can’t fix it myself, I will at least know what’s wrong. When you live in an apartment, they don’t let you touch these things. If you live in a house and don’t know what you’re doing, it can be dangerous. But I do know what I’m doing. If my faucet is loose, I tighten it up.”

Matt Gifford sees the Phoenix Commotion’s work with homeowners as part of a bigger change of mindset: Building and maintaining a home isn’t beyond their reach. He sees building one’s own home as a great first step toward living a self-sufficient lifestyle in a corporate world: “It’s not rocket science. That’s what we try to teach people. People don’t think about picking things up and playing with them like this. They don’t think it’s possible to do it themselves. They think you need a specialist, because of the way the market is constructed. To break down that divide between ‘us’ and ‘them’ culturally, we need to interact. We need community. Instead of our culture being so devoid of self-reliance, we should not be afraid to get our hands dirty, to have our input.”

Learning to Live Simply

The Phoenix Commotion isn’t building luxury homes. The functional, efficient spaces are designed for sustainability in size as much as in materials and efficiency. Downsizing is a growing housing trend nationwide, with the average American home size down in 2010 for the first time in 50 years, according to research by Trulia, a real estate search engine. Smaller homes are a growing trend in part because they are perceived as a route to a simpler life. Phoenix Commotion administrative manager and homeowner Kristie Stevens rented another of Dan’s small homes — called the Storybook House — before buying her own Phoenix Commotion home. She recalls, “Before I lived in the Storybook House, I lived in a 1,400-square-foot house that had two bedrooms and one bath, a huge living room and a huge dining room. And I spent the majority of my free time cleaning it. I had two kids and a white linoleum floor, which I despised. When I got ready to move into Storybook House, I had to shed a lot of furniture, some I had paid a lot of money for, some I had inherited. It was painful. It was psychologically difficult to get rid of all that stuff.” But Kristie says the payoff was having a more manageable home that allows her to spend more time with her family and less time cleaning.For her, the stuff she got rid of is much less valuable than the time and simplicity she received in return.

Enriching Community:

Enriching Community:

The Phoenix Commotion Neighborhood

After more than a decade, Phoenix Commotion has had a big impact on Huntsville, Texas. Entire neighborhoods are filled with Phoenix Commotion homes, and their unique style makes them attractive to buyers of all income levels if the original owners move out. Regular people all over Huntsville are eager to move into a Phoenix Commotion home. But Dan Phillips is sticking to his mission of creating homes for those in need. “Homeownership was never meant to be a profit center,” Kristie says. “Homeownership should be a right, not something for the elite.”

Kristie has seen through personal experience what many studies have shown throughout the years: Owning a home makes people more active members of their communities. “When you own a house, you have neighbors, and your kids play in the street. You pay taxes, and you care that the police are doing their business. It makes you much more invested,” she says. Before she built her own Phoenix Commotion home, she rented another of Dan’s houses, and says it was the first time she had experienced a secure home and neighborhood: “It was the first time I felt safe letting my kids just ride their bikes down the street. When you live in an apartment, you have to be careful. You don’t know the neighbors. Here, we were all neighbors, and we all knew each other. That neighborhood was transformed over the years.”

Living in an established Phoenix Commotion neighborhood showed Kristie a vision of how these homes could transform whole sections of the city. It inspired her not only to want to build a Phoenix Commotion home, but to want to build more Phoenix Commotion neighborhoods. She built her home in a rough area of town, hoping she could set the cornerstone for a neighborhood revitalization. “I knew before I moved in that there were some issues in this neighborhood, but I’ve talked to the city manager quite a few times because I am a home owner and I do care. In the two years I’ve lived here, it’s improved dramatically,” she says. She fancies taking over the town. “Just two blocks away, one of Dan’s former employees is building a house, and there’s another employee planning to move into this neighborhood. We’re kind of taking over in the same way it happened in that other neighborhood. We’re essentially revitalizing this part of the city by putting more homeowners in it.”

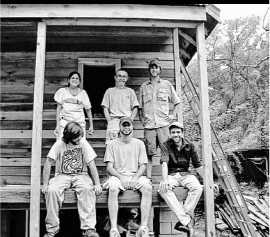

Dan Phillips (back center) and his crew of workers and volunteers.

Along with building safer, stronger communities, increasing the number of homeowners is great for a city’s economy. More homeowners means more paid taxes. Providing low-debt homes means community members have more money to reinvest into the local economy. “In Huntsville, there’s not a lot of affordable land. Only about 40 percent of people own their homes. It’s one of the poorest counties in the state, because not enough people own houses and pay taxes to support the infrastructure to have a sustainable community,” Kristie explains. Although sustainable houses are important to a sustainable community, that’s not enough, according to her: “A sustainable community is something close to the amenities you need. It’s safe. The creation of more sustainable communities isn’t just about the houses, it’s about the people.”

What Did He Do with All That Stuff?

Dan Phillips is a master of creative reuse. Here’s a small example of some of the things he’s done with unusual items:

• Picture-frame corners from frame stores samples: Colorful, zig-zag ceiling

• Crystal relish platters: Porthole-like windows

• Wine corks: Laid and grouted into floors and countertops

• Wine bottle bases: Stained-glass-like circular windows

• Broken tile and mirror shards: Laid and grouted into floors and countertops

• Thousands of bottle caps: Grouted tile flooring, wall mural

• Broken ceramic mugs: Wall mosaic

• License plates: Roof shingles

• Old cattle bones: Decorative accents, drawer handles, house address numbers, grouted countertop

• Bois d’arc slices and branches: Grouted coun-tertops, stair railings, banisters

• Bondo-filled egg shells: Decorative elements

• Beer bottle labels: Flooring collage

• CDs: Wall and ceiling mosaic

• Papier mâché, sealed: Flooring

• Reclaimed windows: Greenhouse walls

• Champagne corks: Flooring and drawer pulls

• Corrugated metal: Rooftops

• 2-by-4 trimmings: Walls, ceilings, roofs

• Crushed aluminum cans: Shed siding

• Beer keg tap: Faucet

Planting the Seed: Volunteers and Interns

Planting the Seed: Volunteers and Interns

Dan Phillips has trained hundreds of volunteers and interns in the 13 years since Phoenix Commotion’s inception. Part builder, part teacher, part social activist, Dan sees the value in spreading his message of reuse, even if it means his building projects require more complex coordination. “From our university in Huntsville, we get students who want service projects, community service hours or just want to volunteer. They come out in droves, which takes a lot of planning, but what you get in return is you have inoculated these people to demand something other than the mass-marketed materials and designs that produce cookie-cutter houses.”

In order to make the most of volunteers, Dan has to come up with projects that dozens of totally unskilled workers can learn and repeat for several hours. But his penchant for instruction and the simplicity of many of the tasks required to build a home make the volunteerism pay off for both student and project. “When 25 people arrive on your job site, you better have something for them to do. We often have these people for three to four hours, and there’s not time to train them to use a chop saw or nail gun,” he says. “But we can organize lumber, build a fence, put down mosaic — there are a number of things that can be done by people who just arrive.”

But Dan doesn’t take on hundreds of volunteers because he needs someone to build fences and lay mosaic. He knows the most important part of making grassroots change is getting more individuals involved. Every community member who becomes involved with Phoenix Commotion is another advocate for alternative building — or at least someone who has had the opportunity to see a different way of building and creating community. He says, “The idea gets spread, and who knows where that will lead. You get the idea out there. You talk to somebody, and they talk to two people.... it’s exponential. It becomes a little groundswell. I’m not saving the world here, but that’s the idea.”

Building homes for ourselves and others is a direct way to build community. Most of us can say from personal experience that we learn to appreciate and understand one another better after we’ve worked toward a common goal. Dan says that desire for community is what attracts people to his program: “When we build a house, the volunteers come out. Buried in the most primal parts of us is the instinct to help each other — barn raising, helping someone change a tire. If you can tune into that part of the human psyche, you’ve done something.”

Dan’s protegés take with them not just the desire to do good, but the desire to spread the ideas instilled in them through their work with the Phoenix Commotion. For Matt, the biggest impact of the program is “the ability for it to change minds and touch people.” He loves the process and the practical applications, but spreading the message is an important part of the overall goal: “You’re getting your artistic itchies out, and each house is unique, and that’s great. And you’re building for low-income families, and that’s great. But it’s more about all the people who come through on a daily basis and see these ideas.”

After Jerrod, currently a professional musician, completed his internship, the Phoenix Commotion way of thinking leaked into all the parts of his life. “The thing I took away was you don’t have to spend big gobs of money. Do it yourself. The more you can do it yourself, the more you know about it, and the less it costs you. That’s what I think about my band, and that’s what I think about houses.”

Jerrod attributes Dan’s success at spreading his message to his intense passion. “The main thing that makes him so good is that it’s what he wants to do. It’s his passion. About anybody who takes hold of what they want to do and does it for eight hours a day, I guess they could find a way to make a living out of it if they wanted to. He wanted to build art. He wanted to help people.”