A Rise in Deconstruction

A Rise in DeconstructionCHAPTER 8

MAKING

DECONSTRUCTION

THE STANDARD MODEL

Creating a national model of deconstructing

buildings and reusing their parts

offers environmental, social and community

benefits to our nation.

DECONSTRUCTION— disassembling structures and reusing the building materials — is an idea that has gained popularity over the past 20 years. Still, the number of homes demolished every year greatly outweighs the number of homes that are deconstructed. In conventional demolition, entire structures are bulldozed, resulting in a pile of mixed debris, all of which is sent to the landfill. Occasionally, demolition or salvage crews cherry-pick, removing the most accessible, valuable, easily reused materials from a home, but deconstructing and reusing entire homes is a rarity. Demolition is the standard method of removing structures from building sites.

While it’s not mainstream today, “deconstruction” is a relatively new term used to describe an old process — the selective dismantlement or removal of materials from buildings instead of demolition, according to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Bob Falk, president of the Building Materials Reuse Association, a Chicago-headquartered national non-profit dedicated to raising the awareness and popularity of deconstruction, says it’s nothing new: “Decades ago, taking apart buildings and reusing the parts was standard practice. We’re seeing a renewal of interest in an old way of doing things.”

A Rise in Deconstruction

A Rise in Deconstruction

Formed in Canada in 1994, the Building Materials Reuse Association (BMRA) became a US-based organization in 2004. The group’s mission is to educate people about the many benefits of deconstruction, and it hosts a biennial conference called DECON where those involved and interested in building materials reuse learn how to efficiently salvage and reuse building materials and how to spread deconstruction’s benefits. The BMRA isn’t alone. Groups fostering the reuse of materials and businesses that sell salvaged building materials have been springing up with increasing regularity all over the US. Habitat for Humanity launched its first ReStore just 20 years ago; they sell donated and salvaged building materials from deconstructed and remodeled homes. There are now more than 700 ReStore locations. The BMRA estimates that hundreds of other for-profit and not-for-profit businesses and organizations countrywide revolve around the use of reclaimed building materials.

Our nation experienced a change in mindset after the Industrial Revolution. Before the advent of mass production, we valued craftsmanship and high-quality materials because items were expected to last a lifetime. But cheaper materials and an increase in our speed of production shifted our values toward efficiency. It’s led us to develop practices that favor expediency over high quality. “We used to put a higher value on craftmanship and quality materials in contrast to today’s focus on profit-based efficiency,” Falk says. “Also, there has been a change over the past several decades, especially since World War II with the development of heavy machinery and worker safety laws.” Though worker safety is paramount, safety requirements have resulted in rules that keep workers in machines, rather than allowing them to use their hands and disassemble and recover usable parts. “It created a disincentive for salvage and reuse,” Falk explains. “The tendency has been toward tearing something down with a machine and throwing the materials away rather than taking it apart and reusing the materials.” The BMRA was formed to help reverse that trend.

Environmental, Community and Economic Benefits

Environmental, Community and Economic Benefits

The BMRA advocates the many benefits of building materials reuse. The first major benefit is environmental. Building materials reuse is a means of “conserving our natural resources by preserving quality materials,” Falk says. “Most of the lumber crunched up in home demolition is our old-growth forest, and that will never be available again.” By reducing waste and reusing quality materials, we take advantage of the resources of the past and reduce the need for new materials production.

Building matrials reuse also benefits communities in other ways. Building a thriving deconstruction industry would create jobs. Deconstruction and the process of transporting, cataloguing and selling used building materials require more human involvement, and therefore more jobs, than demolition. “Rather than one guy in a big excavator that’s crunching a building, and another in a truck that’s hauling it to some distant landfill, you can put the cost of that building removal, as well as the value of the salvaged materials back into the local community in the form of more jobs,” Falk states. The tasks involved in the emerging deconstruction industry require a wide range of skill and interest levels, providing jobs to members of all levels of the labor force. “One of the advantages of deconstruction is that it’s not rocket science,” he adds. “Taking apart a building and salvaging materials is less complicated than constructing a new building. You can offer people that have few job skills a means to learn some basic job-site safety, working with and around machinery, proper tool usage, and the like. So, the actual deconstruction process itself can help train people for jobs in the growing deconstruction industry or in the broader construction industry.” Builders of Hope offers a great model of an institutionalized system of deconstruction and community on-the-job training (see Chapter 9).

Along with jobs that deal with the hands-on process of deconstruction, reuse also supports ancillary businesses that process and sell reclaimed materials. “You can sell the materials you salvage, so there’s an opportunity for people to start small businesses, which teaches how to inventory and manage materials, and how to distribute and market them,” Falk says. Businesses already working in the industry range in size and scope, and there’s plenty of room for increases in these types of businesses. “This is not necessarily just a little corner store that sells a few hundred dollars’ worth of materials,” Falk explains. “Some ReStores, dealing with both donated and deconstructed materials, do $2 million worth of business a year. So we’re not just talking about low-end, unsustainable businesses. Interestingly, and in spite of the down economy, many reuse businesses in our membership have been reporting very positive sales. I think more and more shoppers are realizing that quality materials can be found at reused building materials stores and at lower prices than the big box stores.”

Salvaged building materials are valuable, and urban centers can directly benefit from keeping that flow of resources in the community. “It’s an economic benefit to the local community, rather than all of that value being exported to the landfill and being forever lost,” Falk says. In many cases, the urban centers with the most abandoned buildings and with the greatest need for deconstruction services are also those with the greatest need of low-skilled employment opportunities. “Many of our eastern Rust Belt cities, where there has been mass migration from the inner city and there is a lot of abandoned housing that needs to be removed, are the very same places that have an employment problem. With an emphasis on employing people, deconstruction can be an important element to help transform distressed neighborhoods into more sustainable communities,” Falk suggests.

What Deconstruction Builds

What Deconstruction Builds

When resources are kept within the community and become the catalyst for new industry, the entire city benefits. “When you have a business that’s employing people, it provides a larger tax base for the community. It employs people, ups their standard of living and provides materials for the community to rebuild infrastructure,” Falk says. He sees deconstruction working hand in hand with other community development projects to create communities that are more self-sufficient: “In the inner cities, we’re seeing this growth of urban agriculture and creative reuse of the abandoned land. Deconstruction dovetails with these other efforts to create opportunity in areas where there hasn’t been much hope.”

By reusing building materials within the community and hiring local community members to both dismantle and rebuild, communities can create a closed loop of reuse within communities. “It provides materials for construction, in the same way these urban farms provide food for their communities,” Falk explains. “It’s one element in developing a sense of community, rather than being totally dependent on outside sources for food and building materials. There’s a richness of materials in these buildings. Some people just see it as trash, but there’s a lot of intrinsic value. I think all of us feel better about using things that we produce or generate locally than about using something that comes from a far-away factory.” Communities also benefit by retaining elements of their shared past, and holding on to longstanding cultural elements. “There’s a way of preserving some of the community history by reincorporating these materials back into renovation in that community,” Falk adds.

Implementing deconstruction as an alternative to demolition has been a challenge in many cities. “Deconstruction is still foreign to a lot of people who regulate building removal, however that trend is changing,” Falk says. While more cities are becoming deconstruction friendly, the licensing requirements, training requirements, and building removal ordinances in most need to evolve to better accommodate deconstruction and building materials salvage as an alternative to demolition.

But Falk is optimistic. Awareness of deconstruction as a viable method of building removal is growing. “While not mainstream nationwide, more and more people are looking at deconstruction as a building removal option to demolition. Our association has gotten more attention and our membership is growing steadily,” Falk reports. As cities take on their problems with blighted inner-city areas, deconstruction is an idea that’s spreading fast. “We’re getting a lot of interest from municipal folks who deal with redevelopment efforts and workforce development. They are starting to understand the connection that deconstruction can make between building removal efforts, job training, small business development, and community redevelopment. Some cities are pretty progressive, such as Seattle or Portland. However, interest is growing on the East Coast as well. Middle America is catching up and there are centers of real interest. In Iowa, for example, we’re working with the state, and they’ve been very open-minded and forward-thinking. We’re making good progress, but like any effort at social change it takes some time to get the habitual ways of doing things to change,” he says.

Guy and Kay Baker estimate they spent $20 on the kitchen; hinges and doorknobs were the only things they paid for. Kay laid the wood-block countertops herself.

The Bakers love spending time outdoors, and designed their home for comfortable, year-round outdoor living.

Photos: Michael Shopenn

The Baker home is something of a museum of its region’s architectural history. Guy says the home includes something from every town in his county.

Guy had a cattle trough lined with fiberglass for a huge tub with a $90 price tag.

Photos: Michael Shopenn

Meghan and Aaron Powers built their Idaho straw bale home with the help of friends and family who camped out during construction.

A grain bin was converted into a combination office/ workshop and guest house.

The Powers employed a number of clever space-saving techniques in their 836-square-foot home, like the sunken dinner table beneath removable planks of the living room floor.

Photos: Betsy Morrison

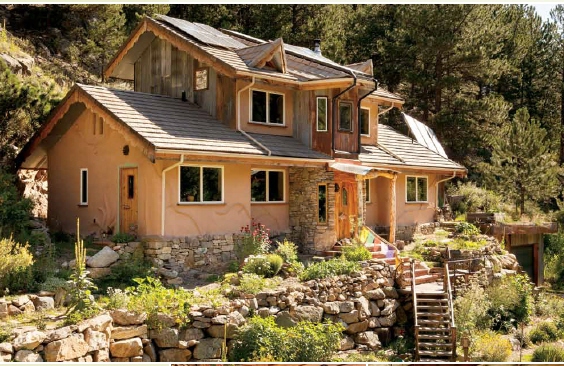

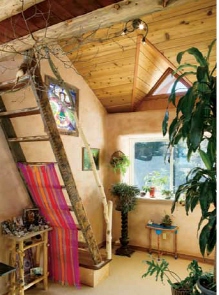

Rick and Naomi Maddux’ handbuilt, straw-bale home was a work of art they built with friends and neighbors over several years, and with no construction loan.

They wanted their home to be unique and imbued with character. One of their design requirements was to avoid hallways.

Photos: Paul Weinrauch, courtesy

Boulder County Home & Garden

magazine.

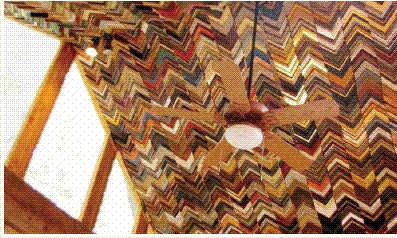

Inside the Phoenix Commotion Treehouse Studio, frame corner samples from a photography framing store combine to create a zigzag-pattern ceiling.

Photo: Courtesy Phoenix Commotion

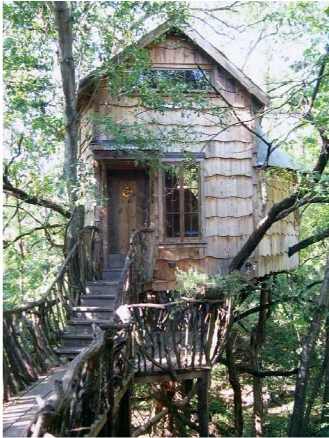

The Storybook House is one of dozens of Phoenix Commotion homes that are taking over whole sections of the city.

Wood log “disks” laid in concrete create a gorgeous countertop.

Photo: Courtesy Phoenix Commotion

HabeRae rescued an abandoned 1950s firehouse in a dangerous part of the city. Now a 5,000-square-foot mixed-use building, the space offers a bagel shop, a salon and nine residential lofts.

A classic example of urban infill, Haberae’s “2 on Watt” project was built on an abandoned lot in an old part of Reno. The cottage style was designed to fit in with the homes’ historic surroundings.

Photos: Pamela Haberman

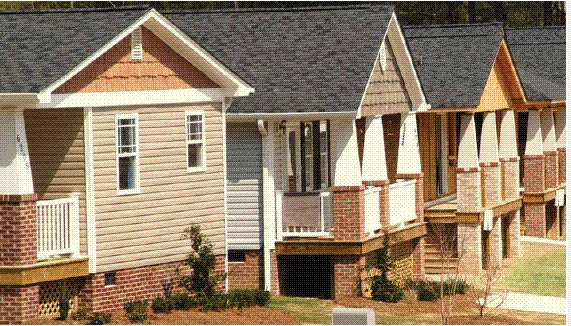

Builders of Hope rescues scheduled-for-demolition homes and either renovates them in place or moves them to whole new neighborhoods made up of buildings they have rehabilitated.

Design features such as front porches and positioning on cul-de-sacs increases the sense of safety and community in Builders of Hope neighborhoods.

Photos: Courtesy Builders of Hope