A North Carolina program rescues landfill-destined

homes and gives them new life as foundations

of low-income neighborhoods.

IN NORTH CAROLINA, the Builders of Hope program rehabilitates rundown homes, creating eco-friendly dwellings for low-income families. In 2006, after inheriting a small amount of investment capital, Nancy Murray left a career as an advertising executive to found the non-profit. “I was at a point in my life where I had the opportunity to do a career change,” Murray says. “I always had the inspiration, even as a child, to make a difference in the world, but I didn’t know how. My father passed away and left me some money, and I thought, ‘Well, I could put it in the stock market’ — not knowing it would crash — ‘Or I could save up for retirement, or I could do something significant.’ My husband and I decided I should start a non-profit to help others. We were in the position to do that, and I felt very fortunate.”

Murray wasn’t exactly sure what type of non-profit to start but says, as she was considering the question, it seemed as if the universe was working to demonstrate to her the severe lack of low-income housing in Raleigh. She continually met people in need of high-quality housing near the city center where they worked. “I started it as a ministry,” she recalls. “People kept coming into my life, either through church or other groups, who had to travel a long way every day to get to work.” She started looking into the local housing market and considering how difficult it was for working, low-income people to make a good life for their families in the city, given the available housing options. “Really, for the last 30 years, if you’re a teacher, firefighter, secretary, worker at a non-profit — any careers that are really great careers but not on the higher end of the pay spectrum — you have the choice: It’s either substandard housing in the city; or you can live in the suburbs, get some property and one small vinyl house and commute.”

Once Murray started to realize how few housing options existed for low-income urban workers, she became interested in how much housing was going to waste in Raleigh. She started noticing new buildings being built around the city and began to pay attention to what was happening to the existing homes. “Things started coming together,” Murray explains. “All the rich neighborhoods were tearing down houses left and right with wood floors and granite counters. The land was worth more than the house, so the house would go to the landfill. Then I realized how many: 40 to 50 houses a month just in the one town where I started!”

Builders of Hope founder Nancy Murray realized the connection between the number of homes being torn down and the number of people in need of affordable urban houses, and she designed a non-profit that brought the two together.

Murray quickly envisioned an elegant solution that helped solve two problems at once: All the homes being sent to the landfill were the perfect fodder to create homes for all the people in need of decent places to live. And with that, Builders of Hope was born. Murray felt dedicated to three goals: first, to provide homes for working families; second, to keep all those high-quality, usable building materials out of the landfill; and finally, to make a difference in the greater community by providing jobs for unskilled workers. “I realized, first off, our planet cannot sustain this,” Murray says. “There are more people without housing than ever before, and we’re sending all these houses to the landfill. And I wanted to make a difference not only for the people who moved in, but also those who build them, so I decided to hire people from homeless shelters.”

A Non-profit Is Born

A Non-profit Is Born

In 2007, Murray founded Builders of Hope, a non-profit that purchases teardown homes, rehabilitates them and sells them as low-income housing. Committed to sustainability from the recycling of the home to the health of its materials, she creates durable, energy-efficient homes, working with national organizations and programs such as the US Green Building Council and LEED. “The Builders of Hope model has successfully been able to address the major issues: How do you take this inventory and make it beautiful and sustainable and eco-friendly,” Murray reports. “We work with LEED, so we’re energy-efficient. We strive for superior indoor air quality. Everything is about the end user — the tenant or the homebuyer.”

It has absolutely worked, confirms homeowner Josh Thompson, who moved into Builders of Hope’s State Street Village in Raleigh in May 2010. He describes living in a Builders of Hope home: “It’s a phenomenal experience. The overall quality of the home has made me feel confident that it’s going to endure.” He adds that the quality of materials in this home compared with other affordable places he has lived puts his Builders of Hope home in its own league: “There’s so much cheap construction out there, homes built of concrete slab or vinyl siding, but Builders of Hope uses superior-quality materials. It makes the experience awesome.”

Builders of Hope homes are special to homeowners for reasons outside their longevity and high-quality materials. They love their homes because they are custom-built to fit the end users’ specific needs. “The design of our house is not excessive,” Thompson says. “But they took the time to figure out my family and priorities in life, and they designed a house around that. They say, ‘Oh, you want kids? Let’s give you big bedrooms. You want to host events? Let’s give you lots of space.’” Thompson and his wife host weekly church get-togethers for 30 to 40 of their friends, and he says it’s quite comfortable in their 1,600-square-foot home, thanks to the Builders of Hope designers’ attention to detail and wise design.

Murray carefully considers the elements that go into her homes, examining them in terms of durability, efficiency and health. Making homes work for homeowners is her end goal, and that sometimes means choosing among many sustainable building options. She designs every home with the hope that one family will live in it for 20 or 30 years or more, meaning she often chooses quality over low cost, or durability over environmentalism.

Murray learned that we demolish 250,000 homes a year, and that we send nearly all of those building supplies to the landfill.

One example is the selection of exteriors. No fan of inexpensive vinyl siding, which she says only lasts for about 15 years, Murray uses only Hardiplank siding on her homes, an eco-friendly, durable option, but a more expensive one. The higher-quality materials pay off over time, Murray says. By choosing Hardiplank, she can be assured homeowners won’t have to worry about a dilapidated exterior in need of replacement in a few years. Murray cites another example: “All the houses need insulation. There is generally no insulation in homes built prior to 1965. We use blown-in foam insulation. It’s more expensive, but it gives you the opportunity to really seal the house. It’s superior-rated in terms of insulating quality.” That means they will be less expensive for homeowners to maintain over time, something Murray considers equally important as a low initial price.

Murray also insists on quality over quantity for her homes’ heating and ventilation systems, a crucial component of healthy indoor air quality: “You must get a high exchange rate on the HVAC [Heating, Ventilating, and Air Conditioning]. You pay more to update the HVAC with a higher indoor/ outdoor air exchange, but then if there’s any yucky stuff inside, you’re not sealing it all in.”

And though Murray is always willing to spend more if quality is at stake, she is also willing to forego efficiency-enhancing systems if it will sacrifice longevity or economy. “This is an example,” Murray explains. “You get big LEED points to be rated for solar, but solar is ridiculous for us. There’s the opportunity for it to get broken or smashed. In some neighborhoods, it’s a high likelihood.” Though her homeowners could save on electricity by using solar power, the expense of maintenance for complex technological equipment doesn’t work for her specific clientele. “Even if they don’t get damaged, in 15 years, most solar panels will have to be replaced. I have to ask myself, ‘In 15 years, can that homeowner spend that amount to replace it?’ Chances are no — it’s not a sustainable solution, so we have to come up with a better way.”

Updated with durable, efficient, modern amenities including new roofs, efficient windows and cutting-edge HVAC systems, Murray designs her rescued buildings for the families who will live there.

Though compromise and tough decision-making are always necessary in Murray’s world, homes must meet the highest green standards possible, and she continuously quests to perfect the product she provides: “Part of all sustainability is really challenging each other, and not accepting no for an answer. If we haven’t figured something out, it just means we haven’t figured out how to do it yet. We’re constantly challenging the people we work with to keep it green and affordable.”

Sustainability at Large

Sustainability at Large

Builders of Hope makes big headway on the sustainability front by starting with reclaimed housing stock. And, though she’s committed to the health of her future homeowners and their ability to maintain their homes over time, Murray’s interest in sustainability extends beyond her homes’ residents. She also hopes to benefit society at large by confronting the huge housing waste problem in the US: “We’re taking a house that’s been rendered functionally obsolete, and we’re completely rebuilding it, turning it back into tax-generating revenue stream and offering it up as affordable housing.”

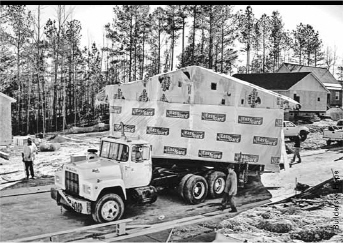

Builders of Hope rescues scheduled-for-demolition homes and either renovates them in place or moves them to whole new neighborhoods made up of salvaged buildings.

Murray believes increased home-ownership leads to proud families and healthy communities, and she knows healthy housing for low-income residents is very hard to find. “In every city and even rural towns, there is a huge shortage of affordable housing. Raleigh is 23,000 homes short, yet homes are sent to the landfill every day,” she reports. “There are 33 million homes across the country that were built before 1970. That’s 40 years or more of housing stock, and there’s no national program for rehabilitating it and making it green.”

If Murray is amazed at the amount of waste we’re sending to the landfill, it’s because she’s seen how much of it we can save and reuse, adding that “25 of our houses represent 1.5 million pounds of debris rescued from the landfill.” Murray says when we compare the amount of homes we toss in the garbage heap with the numbers of new homes we need, a fundamental paradox is revealed: “Of the 33 million pre-1970 homes, 250,000 are torn down every year, and those are just the ones tracked by the EPA. There aren’t enough holes in the ground to be able to withstand this. It’s a teardown epidemic. It’s not sustainable, and as a country we need to figure out a better way.”

Builders of Hope Homeowners

Builders of Hope Homeowners

Murray aims to provide quality homes for the demographic of families that don’t qualify for most social programs, but that can’t afford a home on the standard market. “All of our buyers hope to get conventional financing,” she says. “Our houses range from 60 to 120 percent of the median house value. Habitat for Humanity aims at about 35 to 55 percent of the median house range, and most of their clients are people who can’t get mortgages.” Murray targets low-income working families who have been pushed away from the urban centers where they work. “They’re often first-time homeowners who have grown up on public housing. They’re young families who can’t afford anything otherwise.”

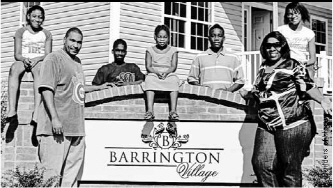

Dawana Stanley is president of the Barrington Village homeowners’ association. Every Builders of Hope neighborhood has community groups that help residents get to know one another by hosting parties and study groups and connecting with outside community groups.

Homeowner Josh Thompson says the location and design of his home has changed his family’s life: “We have friends in the neighborhood, and there are so many other children. The location has changed my quality of life.” Thompson appreciates that his home is located not only in a safe, friendly neighborhood but also in the urban center, where most of his activities are located. He feels that living in the city helps him teach his young children to be thankful: “My kids get to see diversity, because our home isn’t isolated away from poverty. They aren’t growing up in an environment that says, ‘This is what you automatically deserve.’ They get to see that they’ve been given a gift of a quality house, and not everybody has that.” A city-lover, Thompson didn’t want his kids growing up in the isolated suburbs, where every neighborhood the family could afford was filled with mass-marketed, cookie-cutter homes filled with cheap plywood and vinyl. Living in a Builders of Hope home teaches an appreciation for reuse, and for giving back. “Even at my son’s age of three, he understands that Christmas isn’t just about getting presents,” Thompson says. “He sees that the people across the street don’t have something, and he asks, ‘What we can do to get them some gifts?’ Builders of Hope lets me teach my kids that.”

Murray also appreciates the lessons she’s learned through her work with Builders of Hope. She says the program has shattered any remnants of naïveté from a sheltered upbringing: “My dad raised me to be white collar, with a big-business mentality. We’re an IBM family. Growing up on the other side of the fence, I never really understood the impact that housing has on people. I grew up thinking substandard housing is like that because the people who lived there didn’t take care of it. But it’s like that because the landlord doesn’t take care of it. People live where they have to. You might say they could live elsewhere, but they can’t. Every city has shortfalls of affordable housing by thousands of units.”

Murray is committed to putting families into high-quality homes they can afford, and she has included several fail-safes to encourage and support families so they are able to stay in their homes for many years. “We sell the houses at our cost. Let’s say a house was appraised for $150,000, but our cost to build was $135,000. We would sell the house for $150,000, but we would only require the homeowner to bring $135,000 to closing,” she explains. “We take the extra, and we hold onto the second mortgage, which is 100 percent forgivable. Every homeowner has closed with equity on the table.” The second mortgage, which covers the difference between the home’s construction costs and appraisal value, is forgiven over time as the homeowner stays in the house. After five years, a portion is forgiven. If the homeowner stays in the home for ten years, the entire second mortgage is forgiven, increasing the home’s equity.

Builders of Hope Neighborhoods

Builders of Hope Neighborhoods

Murray has two models of building Builders of Hope neighborhoods. The first is to buy scheduled-for-demolition homes in the inner city, rehabilitate them where they stand and make them the cornerstones of entire renovated neighborhoods. The second is to pick up several tear-down houses from different areas of the city and move them to create new urban neighborhoods made entirely of Builders of Hope homes. When homes stay in place, Builders of Hope often tries to buy five to ten homes on the same street and build a cohesive community.

Design features such as front porches and positioning on cul-de-sacs increases the sense of safety and community in Builders of Hope neighborhoods.

Murray wants to improve more than the individual homes her residents can afford in the city; she wants to improve the quality and safety of the communities they can live in, as well. Though she was aware of poor inner-city conditions, she says that until she started working in a field related to substandard housing, she hadn’t realized how poor inner-city living conditions could be: “To give you an example, in many of these places, you have to bring your own appliances, including stoves. In one unit, a window air conditioner was stolen and never replaced. There will be gaps under the door big enough that rodents can just walk right in. These are people who are working, not just those without jobs. We find people living in crawl spaces.”

Working in blighted neighborhoods and getting to know their residents has shown Murray that the structure of the current urban housing market is the root cause of much of the destitution. Inner-city low- to middle-income people can’t afford decent places to live, which leads to community-wide despair, lack of civic involvement and increased crime levels. “Right now, we’re revitalizing 40 apartments and 25 single-family homes on one street. On this street, there’s prostitution and a market where they are selling drugs,” Murray says. “There’s a guy who is about 70 years old who comes to one of our sites, and he calls me Mother Teresa. He said, ‘You are the first one ever in my entire life that has come into this neighborhood and built something for us. Every time someone comes and builds something new, it’s something we can’t afford.’”

Murray wants to provide high-quality housing for the people who already live in urban neighborhoods — not to price out current residents and bring in higher-income homeowners. “We’re about going into the neighborhood, hiring from the community and building for the actual people. These ghettos were formed with invisible walls and barriers. When all the people moved out and built the suburbs, no one said, ‘You can’t live here,’ but it was priced so they couldn’t afford to live there,” she says.

Murray designs her renovations with community-building in mind. She always includes front porches and communal spaces and develops neighborhood associations where homeowners get together to discuss safety and other issues. “They work hard to build community, and they do it well,” Thompson says. “They invest extra to give everyone the Internet and a neighborhood communication system, which helps facilitate community immediately. And they have cookouts where all the neighbors can meet each other.” Builders of Hope also helps residents connect with the wider community. “They worked hard to connect me with leaders in the community,” Thompson adds, a task that originates for Builders of Hope long before a homeowner moves in. He explains, “They are really involved in the community. Let’s say the community has an activity council. Builders of Hope goes out of their way to attend the meetings long before they build a community, so when they start the community, they can plug you into it through the contacts they’ve developed.” When he moved in, he met area leaders, teachers and pastors. The revitalized communities are, by design, connected neighborhoods where residents know each other and watch out for each other’s safety. “This tells you the comfort that people feel in my neighborhood,” Thompson says. “My son loves to dress up as an Indian. So here’s my son — he’s three — in the front yard, shining like a light, wearing nothing but a loincloth. It’s an example of how safe my kids — and I — feel.”

Murray is hoping to revitalize urban neighborhoods and to buy up as much inner-city property as she can: “Now that it’s cool to live downtown again, the land is cheap, and it’s getting scooped up.” Developers in most cities buy up cheap land, then build high-end housing there, forcing out longtime residents, and she wants to change the status quo: “These people have lived there their whole lives, then someone comes and makes it beautiful and they are booted out. I’m saying, ‘We’re going to make it beautiful, and guess what? You can stay.’”

Building Green

Builders of Hope lists its key green building ingredients on its website.1

KEY GREEN FEATURES

• Recycling existing homes and useable materials; an average of 65 percent of the structure is reused

• Develop infill locations when possible

• Sustainable building practices and material

• Passive solar orientation

• Spray foam insulation

• Exterior ventilation

• Fluorescent lighting

• Low-emissivity (low-E) windows

• Low-flow plumbing fixtures

• Energy Star appliances and water heater

• Low-VOC materials and sealants (VOCs are unhealthy chemicals that outgas at room temperature from building supplies and interior finishes)

• Upgraded air sealing, insulation and HVAC

• Large front porches to reduce heating and cooling bills

• Rain barrels and drought-tolerant landscaping

Building Inspiration

Building Inspiration

Though she knew building homes would have a positive effect on future homeowners, Murray says she didn’t fully realize the far-reaching effect that improved low-income housing has on entire communities. “There’s another guy who walks around, he is 70-something, he said, ‘I never thought I would be able to walk around this neighborhood and feel safe again. I haven’t felt safe for ten years!’ You think you are doing it for the people who will live there, but it’s the whole community that benefits.”

People who grew up in and moved out of city slums are often thrilled at the prospect of returning to their childhood homes revamped. The people attracted to Builders of Hope communities are frequently people who grew up there and were forced out by unsafe, substandard living conditions. “Folks want to live there again because they grew up there. They want to settle down there again,” Murray says. “I didn’t anticipate how the fact that you’re not tearing down, you’re rebuilding, is very inspirational to those who have lived there in the past.”

Murray also strives to encourage further community and economic development by partnering with companies that normally serve higher-income areas. “Builders of Hope says, ‘What can I do to bring in such and such a company that normally wouldn’t work in this part of town,’” Thompson explains. “They show them these communities, and the opportunities here. A number of suburban companies have been brought into the city.”

The program also connects people from different communities and benefits the people who donate homes. “Through a friend, we met the people who donated our house,” Thompson says. “We randomly went to a get-together at this person’s house, and the person who donated our house was there. From their perspective, they felt the benefits, too. They saw who they were able to help. They saw how their act of sustainability provided an all-wood-floor home for a family. All around, not just from my end, but from the people donating, it’s an awesome experience.”

Despite her wide-ranging efforts to help individuals within her community, Murray might find the most satisfaction in simply telling people currently living in extremely poor conditions that they can move into a healthy new home they can afford. “We worked on these substandard units — out of the 40 units, 20 were occupied and 20 weren’t. First, we rehabbed the empty ones, then we gave current residents the opportunity to stay for the same price,” she says. “Only now, they had a LEED-certified gorgeous home with things like bamboo flooring. You should see the expressions on their faces.” Having a pride-inspiring home completely changes homeowners’ lives, Murray says, adding, “They’ve decorated, their kids bring people over. When you give people a home that breeds dignity, they also get hope and inspiration. It’s amazing what an impact a beautiful home someone can be proud of has on their life.”

Builders’ Builders

Builders’ Builders

Nancy Murray knew that another problem for many low-income workers is a lack of training. For those who can’t afford or don’t want to attend colleges and trade schools, it can be difficult to get high-quality work experience. She also knew that hiring a partially low-pay work staff would help keep her homes affordable. She started the Hope Works program, through which she partners with social service providers such as local rescue missions, workforce development organizations, the Department of Corrections and the Veterans Administration. Program participants learn a high-quality, marketable skill set in construction and remodeling. Because Murray’s homes are built to high green standards, graduates are also well-versed in sustainable building and in renovating homes to meet various green certifications. After six months, participants graduate with a certification as a construction framer and a recommendation for hire from Builders of Hope. The social service providers that Builders of Hope works with to obtain students also help graduates find quality employment. Murray appreciates that, along with providing homes and safe neighborhoods, her program provides an avenue to high-quality employment, and helps reduce the number of people in need of government financial assistance.

Murray’s commitment to the end users of her homes is evident in her commitment to financial efficiency and high output. She says her program is designed to produce homes, not make tons of money or pay high salaries: “If you want to do a comparison, take a look at Habitat for Humanity. They’re in multiple cities, and collectively, they build a ton of houses. But the thing is, they work much like the government. They’re very fat. They have an operations budget of about $2.5 million, and they build about 12 to maybe 25 houses a year. On top of their operations budget, they get all their materials for free, and they get every house sponsored. Comparatively speaking, we have an operations budget of $2.9 million, and we’re building more than 200 units a year, with no sponsors.”

Builders of Hope is able to produce homes so efficiently by performing every task related to the building of the homes, from homeowner applications to design and construction. “We work directly with the homebuyer, and we are the builders. We’ve got our realtors’ license, and we’ve got the architect, land planner and legal counsel all on staff. We wear a lot of hats. We work smart,” Murray explains. Because every aspect of the building process is centralized, Builders of Hope also eliminates the extra costs that often add up as multiple subcontractors work on conventional home sites. “If a homebuyer comes in and wants to make a building decision, we’re the builder, so we can tell them right on the spot — ‘Yes, we can move this wall,’” Murray says. “Usually, you’d have to send the question to the general contractor, then it goes to the architect, and along the way, everyone adds on 20 percent.”

Working efficiently and wisely is only one of many ways Builders of Hope works to keep its homes affordable. The greatest single contributor to creating low-cost homes is starting with donated housing stock. Every Builders of Hope home starts with a donated home that would otherwise have been torn down. Murray says getting homes donated is no difficult feat: “All of our houses are donated. People would normally have to pay $10,000 to $12,000 to have an older home abated and torn down and the site cleared. But if they donate the house, they get a huge tax write-off for the value of the house. Once it’s moved onto a new foundation, that home is an asset with no debt.” Then Builders of Hope takes out a line of equity to rehabilitate the home, and repays the bank when they sell the home.

After proving Builders of Hope could operate with no outside assistance, Murray decided to see how the various programs designed to help non-profits could benefit her output and productivity. Several nationwide programs help provide building supplies to non-profits. “Home Depot has a program called Framing Hope, and we get free vanities and free toilets through that program,” Murray says. “There are other programs, like the [North Carolina] Housing Finance Agency. They pay $4,000 toward sustainability upgrades for a home — there are many statewide programs like that for non-profits.”

Murray’s success meant that government agencies started coming to her. “After Barrington Village, the mayor was so excited, he asked us to do a model of affordable housing for the City of Raleigh,” Murray says. The City had already put together an eight-acre patch of land for the project in the middle of Raleigh. The mayor offered Builders of Hope a zero-percent financed acquisition of the land, which allowed them to begin multiple projects at once. “It’s huge for us. It allows us to do multiple projects at once because we don’t have to buy the land upfront.” Working with city governments allows Builders of Hope to be more prolific, and sometimes to provide homes for less money than they could otherwise. Other counties and cities, including Durham, North Carolina, have offered land deals to Builders of Hope. “In Durham, they have community development block grant funds,” Murray says. “We buy land from their land bank, then the city council votes to pay us back for the land. The City pays for the acquisition, then we pay for the rehab, so it allows us to sell all the houses for $80,000 to $90,000.”

Murray is determined that Builders of Hope houses be extremely affordable. She says other groups often get subsidies and plan to build affordable housing, but unplanned building costs and higher-than-necessary company profits mean the homes end up costing more than most truly modest and low-income families can afford. “Take East Lake in Atlanta. Everyone held it up as the most amazing neighborhood ever. They built this apartment village, but for a two-bedroom, the cheapest rent is $850 a month. The median income there allows for about $500,” Murray says. By reusing homes and building supplies, working with government agencies and procuring a low-cost workforce, Murray creates higher quality homes for less. “I have set out not only to build single-family houses, but houses with their own yard, granite countertops and hardwood floors. And I’m only going to charge $85,000 to $155,000. We continue to strive to deliver more and decrease the cost per square footage.”

Funding Hope

Murray built Barrington Village with no outside financial assistance. She saw that other groups who receive government subsidies to build low-income housing weren’t using their resources efficiently, and she knew doing more with less was the most surefire way to demonstrate a better model. “The first neighborhood I did, we used no government funding. I wanted to prove I could build affordable housing without handouts and do it less expensively than those getting subsidies.”

Oh, Volunteers!

Cheryl Cotter is the service learning coordinator at Carey Academy in Carey, North Carolina, just outside the Raleigh-Durham metropolitan area. Carey Academy provides grades 6 through 12 education, and Cotter frequently sends large groups of students to volunteer with the Builders of Hope program.

Carey Academy students were among the first volunteer groups to work with Builders of Hope, when it was a fledgling program without a formalized volunteer program. As the non-profit’s success and size grew, so did its volunteer program, and the newly formalized volunteer program’s coordinator contacted Cotter to see if she’d like to set up a regular volunteer schedule for students. “I’m always looking for new opportunities that demonstrate the full circle of being an active citizen at any age,” Cotter says. “That’s why I really like Builders of Hope. Here is a woman who started with a dream and took it from there,” she says, referring to Murray’s can-do, make-it-happen attitude. Builders of Hope created a program called Super Saturdays, through which large groups of volunteers converge to help on large projects. Cotter sends 10th, 11th and 12th graders every year, and sends additional students in smaller batches throughout the year. She says all of her students rave about working with Builders of Hope: “They love the demolition. . .whacking a wall. They love taking something apart and then seeing down the road what became of that place. I have yet to hear any of our students dislike or have a bad experience with Builders of Hope.”

Though Carey Academy has no requirements for community service, the school has worked she says. “Just that they learned they could tear out nails or hammer in nails.. That is something they will keep with them when they have their own home or apartment. They are empowered. I think that’s why they always want to go back and do more.”

Cotter says a few particular students stand out when she thinks about her work with Builders of Hope. “I can think of one very quiet young man who was a sophomore — his inclination was not to get out and do service. He hadn’t done it before. When we got there, he was the one out there getting the muddiest, the dirtiest, hefting around more sod than I’ve ever seen!” she adds, laughing. “Another was a young man who’s diabetic. Sometimes I think he had limited himself, but he was hefting this pickaxe to dig a ditch for the water piping. He was just hauling that thing around and having a ball. He was grinning ear-to-ear the whole time.”

Carey students do a wide variety of tasks on Builders of Hope sites. “They do landscaping. They do painting. They’ve done light trim work and framing,” Cotter says. “They can’t use power tools. It’s mostly the smaller interior stuff, like nailing. Their favorite thing is deconstruction.” She teaches her students that every task on the job site is important. The program teaches students flexibility, and about the value of hard work. “When you volunteer, the first thing you learn is to be flexible,” she says. “When we’re there, we’re there to be of service, and to do whatever it is they have determined we need to do.” Regardless of the tasks assigned them, “they always want to go back. Always, always, always.” to develop a culture of volunteerism, and nearly every student participates in volunteer activities. “Here in Wake County, the public schools require volunteerism for graduation. We do not,” Cotter says. “Our school isn’t big. The high-school portion is about 425 students — about 100 per grade, 9 through 12. Of that, almost 300 are in a service club. They choose to be in those clubs. They don’t have to be.” Cotter says Builders of Hope’s location amidst three college towns is advantageous, because the colleges encourage a regional spirit of giving back, and her students dig right in: “It almost seems like osmosis sometimes. They see it, they hear it, they go do it once or twice, and then all of a sudden, it’s who they are and what they do.”

Cotter believes part of the reason students become particularly engaged with Builders of Hope, and perhaps a key to the program’s success, is its emphasis on appreciating its volunteers, and on showing volunteers the value of their efforts. “Their workers at the site have always been the best at taking time to tell the kids what a great job they’re doing,” she says. “They always give heartfelt thanks and explain to the kids how important it is that people volunteer. We hear all the time from them, ‘Wow, you’re doing that a lot faster than I thought you would!’ The kids feel they’ve really contributed and made a difference.”

Cotter loves the sense of empowerment her young students get working with Builders of Hope. The program provides a rare opportunity for hands-on learning for students who spend much of their time in the classroom. “They learn that they have a new skill that they didn’t know they had,”

Cotter also likes that volunteering gives the students lessons in being a good citizen. She frequently invites guest speakers to her class, and a leader at the North Carolina State Service Department comes to speak to the students every year. “He has always stressed to the kids, don’t wait until you have a job and are a taxpayer. You can make a difference now,” she recalls. “He says learn about the community, what its needs are and what interests you, and your community will be better for it.” She says the sense of empowerment they feel when wielding a hammer is doubled when they consider the difference they can make with their efforts: “You don’t have to be a taxpayer to have a voice. Everyone can have a voice, even at a young age.” She tries to show her students additional ways to impact their world. “We do letter-writing campaigns. It’s not just about service, but also about civic action— find out who your con-gresspeople are, see how the system works, and see how you want to have a voice.”

For Cotter, the best part of working with the Builders of Hope volunteer program, though, is when the students see the end results of their efforts and truly understand the value of what they’ve done for another family. “Their eyes are opened to the fact that all humans are the same, and when we all come together, we all can benefit from it. When they’re out there throwing sod around and getting muddy or inside painting or ripping it apart, they don’t totally see it. It’s not until the end when it’s finished and they meet the family — that’s when it really hits them,” she says.