CHAPTER 11

RECLAIMING THE INNER CITY

Two landlords in Reno, Nevada, became inspired

to remodel rundown small spaces in their hometown

and ended up making a big splash.

URBAN INFILL is on the rise. The practice of reusing rundown buildings in urban cores, urban infill is the salvaging of complete structures. Institutionalizing urban infill and creating financial incentives that reward reuse over demolition help reduce architectural waste and revitalizes, rather than gentrifying, blighted urban areas.

In Reno, Nevada, HabeRae Properties is the brainchild of Kelly Rae and Pam Haberman, two landlords who became fascinated with the idea of living better with fewer resources when they built a rural getaway home for themselves outside city limits. “The impetus for building small and sustainable came to us when we bought a remote lot,” Rae says. “The builder who built our little cabin — we were living in New Mexico at the time, near Mammoth — said, ‘You have to go off the grid.’ I said, ‘What is that?’ This was in 1994.” Their builder, Don Berenati of Sweetwater Building, was experienced in off-the-grid, sustainable living, and he explained how the couple’s home could generate its own resources. “He said, ‘You can power it with solar panels; it works!” Rae relates. “And there’s a spring we can tap into with a line that goes to the cistern. So I said, ‘OK, I have to see that.’”

Intrigued by the idea of a completely self-sustained home, Haberman and Rae moved forward with plans to create the cabin. “We went back and forth with the fax — it was before Internet — and before I know it, we have plans for a cabin that’s off the grid. A year later, there’s the plan, and two years later, the house was built with an eight-panel solar system. We were amazed! All of our energy comes from these eight panels, and our water comes from this spring,” Rae explains.

The cabin includes reclaimed materials, such as a salvaged wood floor from a warehouse in Oakland, California. “It was from a shipping warehouse from World War II,” Rae recalls. “It was called ‘the floor that won the war.’” At the same time, the pair was renovating homes in downtown Reno. As they became increasingly impressed by their sustainable cabin, they became increasingly interested in integrating some of those techniques into the homes they renovated. “We thought, ‘If we can make housing better with better insulation and better materials for our own home, why can’t we do this for other people and really do things with value?’ It’s value-engineered. I don’t like the word ‘cheap,’ but it’s economically efficient. There’s a big difference,” she says.

The cabin also employed a number of space-saving techniques. Haberman and Rae wanted a smaller space, and they were impressed with the efficiency Berenati worked into their little cabin. “The spaces fill more than one purpose,” Haberman says. “We have window seats, and underneath are bookshelves. We can cram a lot into a small space, and then you can eliminate the need for a big house. We started doing the same thing with our properties, and we found our tenants were thinking along the same lines we were. They liked the small spaces.”

The two began researching sustainable building, and they learned that for every acre of new land developed, four acres of open space are lost. They decided to change their business direction and focus exclusively on urban infill that features reclaimed building materials. “We saw what was happening here in Reno,” Haberman says. “Reno is a pretty place, and we started seeing all these cookie-cutter developments. It was frustrating because that’s not the city we grew up with. We started looking in the urban core and seeing there was lots we could use without going outside of city limits and cutting into the hillsides and paving everything over.” Their results are wildly popular, efficient urban nests perfect for the city’s large population of young college students and urban professionals. Though they have won numerous awards for historic preservation and community development, the duo says it is most important to them that the projects demonstrate how smart and invigorating reuse can be. But they also say that they are often in the position to fight city hall over rights to reuse and rebuild, rather than being encouraged to renovate rather than demolish.

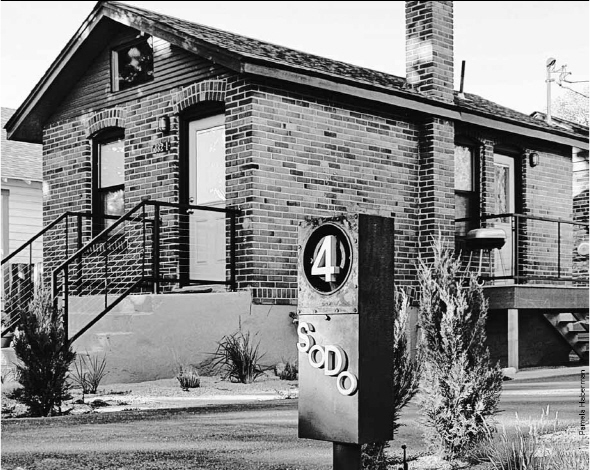

Inspired by their growing knowledge of sustainable building techniques, and disappointed watching their hometown fall victim to urban sprawl, Kelly Rae and Pam Haberman started purchasing rundown urban infill properties and converting them into hip urban homes. SoDo 4 is made up of four 100-year-old, 275-square-foot brick buildings that formerly served as sleeping quarters for railroad engineers.

Building Success

Building Success

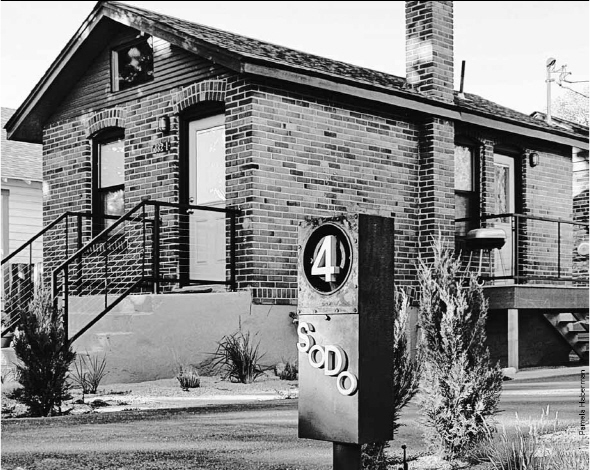

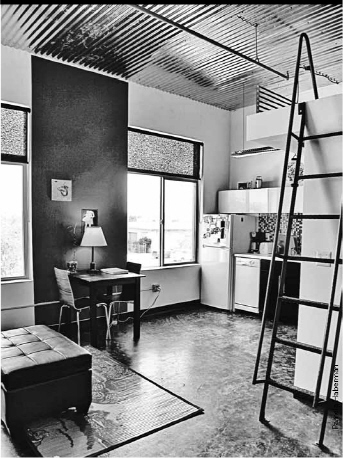

In 2007, Haberman and Rae found four tiny brick cottages, 100-year-old former sleeping quarters for brakemen and engineers on the old V&T Railroad, badly in need of renovation. HabeRae bought the properties, gutted layers of bad interior remodeling materials such as grungy carpet and outdated linoleum and exposed the original century-old Douglas fir floors. They tore through layers of drywall and wallpaper to uncover the original brick walls, which were left exposed in several areas. Reclaimed corrugated metal became an industrial chic ceiling. The two found an old electrical box and outfitted it as a moniker for the SoDo (short for south of downtown) homes. “It’s an old electrical box we found in Unionville, Nevada, a ghost town. We put a stand on it and glued the SoDo 4 logo on it,” Haberman says. “It’s rusted out, but it’s really cool. Instead of having something custom made, we used that — it’s a piece of junk essentially.” Haberman credits her partner for having the vision when it comes to reclaimed materials, for seeing the value in rundown stuff and rundown buildings: “Kelly Rae gets the credit. She’s the alley cat. She gets on her bike and is pedaling up and down the street. Even I will look at it and say, ‘Are you kidding me?’ She’ll see what it can be. It boggles my mind, but she’s done it so many times.”

In the SoDo 4 homes, Haberman and Rae peeled away layers of carpeting and drywall to reveal original wood floors and brick walls. By using salvaged materials, such as corrugated metal ceilings, Haberman and Rae are able to save money; they pass along the savings to their tenants.

Using inexpensive salvaged building materials allows HabeRae to offer a better home for less money. “If I can spend 25 cents on old metal for the ceiling, I don’t spend the money I would have spent on a newly made ceiling. I don’t send what’s there to a landfill. I don’t have to re-ceiling,” Rae explains. “Then I can pass that savings on to my residents. Instead of 800, rent can be 700.” HabeRae calls their small inexpensively maintained recycled homes economically efficient. “When we can do something efficient, we can pass on those savings to our residents, to our clients,” Rae says. Being a small, local company with low overhead and reasonable salaries doesn’t hurt, either. “We all have to make money, by why do you have to make $1 million on the project?” Rae says of her business philosophy. “Why not make $20,000 instead, as long as you have a roof over your head and a good meal on your plate? You don’t have to be a millionaire, just make a decent living and places people can afford.”

For their “2 More on Watt” project, HabeRae purchased two century-old farmhouses just one mile from downtown Reno. They pulled early 1900s newspapers out of the walls, and found photographs of the Italian immigrants who once owned the land.

HabeRae says finding old stuff is easy, and that, though their residents appreciate the savings, they also just like the way old things make a home look and feel. “That old corrugated metal, there’s a plethora of it,” Rae says. “There’s always some guy on Craigslist that had it in a barn. We use it on ceilings and walls. We don’t touch it. It’s rusted and gnarly and knotty, and when people walk into a house and see it on the walls or the ceiling, they’re like, ‘Oh God, that’s cool.’”

Using salvaged materials means no two HabeRae homes are identical. Reclaimed materials bring their own history and story to each project. Rae loves how using old buildings and old materials gives her projects a sense of history: “Buildings have history, and I believe they talk to us. They have the wonderful stories of all the people who lived there, and when a new owner comes in, they start their own story.” She references one of their renovation projects, where they uncovered parts of the region’s history: “Take the old farmhouse on Watt Street. We pulled newspapers from 1902 out of those walls — they were used as insulation. They were newspapers from Italy. All of that area used to be farmland, and Italian immigrants made their home in Reno to farm. That’s a story to be told, and from this point forward, the people in this building make their own history.”

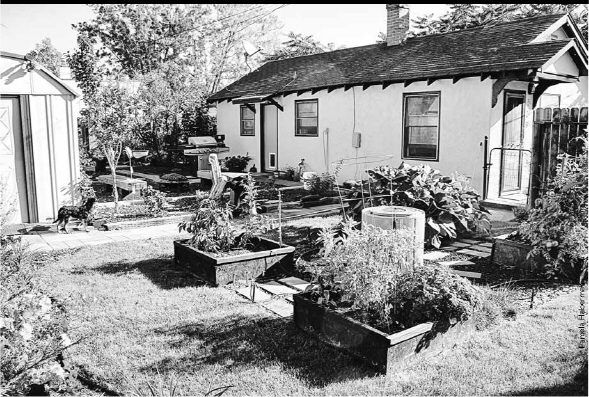

HabeRae adds other touches to make their developments homes, not just houses. They incorporate garden spaces where tenants can grow their own food. “We provide the place, a drip system, everything,” Rae explains. “It’s set up before they move in.” The homes also emphasize access to mass transit and car-free living. “All of our projects are within five minutes by bicycle to downtown Reno or to the university. They’re all on a bus line,” Rae says. “You don’t need a car.” Haberman says their practices attract great residents, many of them young people who are attracted to their properties’ small size and historic feel: “We get much better tenants because they see that we care. They want to live somewhere where the landlord cares.”

Haberman and Rae put a lot of thought into the end user when designing their remodels. They want to create homes that are great to live in and affordable, but also well-designed. “I think what sets us apart in our city is that we know what counts to people,” Haberman maintains. “It has a custom or designer feel to it without it costing a lot of money. We do a lot of unique, hip things. In one place, we took stucco off the walls and exposed the original brick. We reclaimed the flooring — there was carpet, linoleum, adhesive — we took off layer after layer of that stuff to get to the original Douglas fir floors.” She says designing small spaces well also shows people what’s possible in a reduced amount of space: “We have everything self-contained in a very small space. We include everything a person could need — a stacked washer and dryer, a dishwasher — everything a person needs as a tenant. And it’s all in this compact, tight space. Everyone is just clamoring for simplicity, and they don’t always know how to go about getting it. We’re setting the example, and people realize you can live like that. You can live a smaller, less complicated life.”

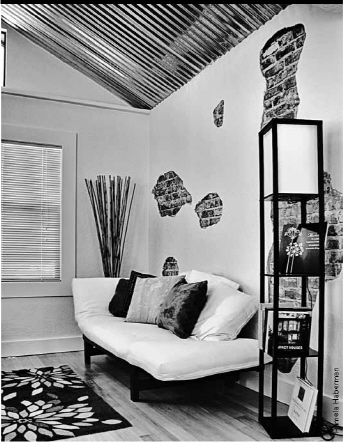

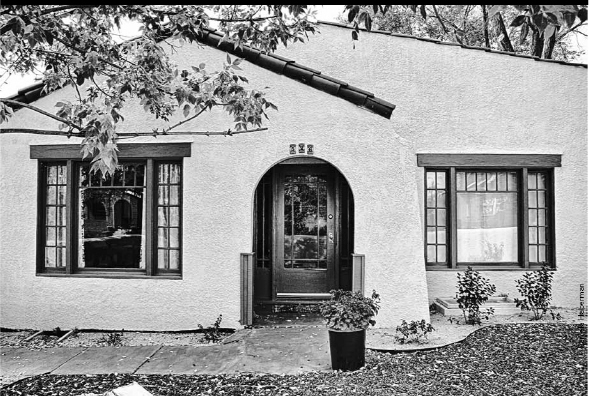

A classic example of urban infill, HabeRae’s “2 on Watt” project was built on an abandoned lot in an old part of Reno. The cottage style was designed to fit in with the homes’ historic surroundings.

Hometown Care

Hometown Care

HabeRae states that their homes make a positive impact on their community by bringing new life to formerly blighted areas, and by providing affordable homes residents are proud of: “We’re always working in the dead areas of town,” Haberman says. “I don’t know why, we’re just attracted to them. The places everyone says you should stay out of, we’re the first ones there.” She loves how their projects become the spark that helps bring life back to dead areas of town. “The next time people come, it’s a whole new area in what was just a blighted area of town. You clean it up, give it some attention, and it attracts people back.”

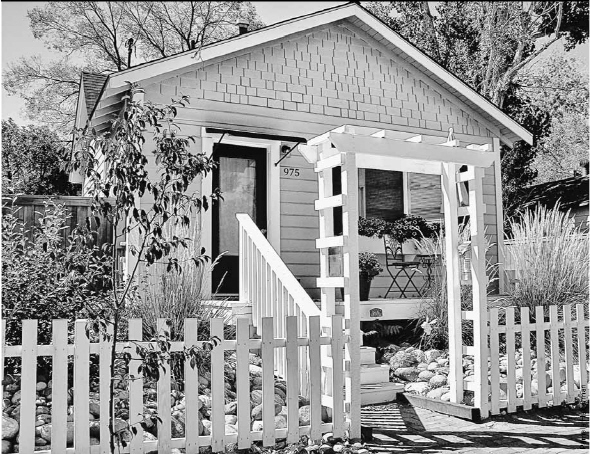

The 2 on Cheney project includes a 1930s Spanish-style bungalow on a front lot and a cottage on a back lot. Both were restored using much of their original materials.

The duo also loves seeing how their efforts encourage community among the homeowners who move in. “When we first finished SoDo 4, the gal that moved into one of them had a huge housewarming party. There were 40 people there, in a 275-square-foot house! They spilled onto the deck,” Rae recalls. She says revitalized neighborhoods where residents feel safe changes the dynamic of an area: “It encourages community. People aren’t so inclined to press the button, go into the garage and press another button when they’re proud of where they live. They want to tell people about it. They want to share their joy.”

HabeRae includes amenities such as built-in garden beds that make living the simple life easy in their homes.

HabeRae also believes their developments support the philosophy of wise urban planning and mixed-use development. They view the renovation of older buildings as vital to communities not just because of the benefits to homeowners, but also because it economically benefits the entire community. Mixing lower- and higher-cost real estate in a community allows for healthy business development, Rae says: “Every community has to have a mix of new and old. The landowners of the older places probably owe less on their mortgage, so the landowners that own those places can charge less in rent from a prospective business. Let’s say they can charge 50 cents in rent. Developers who build these new buildings have to charge $1.50, but the small business owner can’t afford $1.50. You have to give those small business owners a chance to build a company at reduced-rate rent. When they become Microsoft, they can go pay the big rent.”

Kelly Rae and Pam Haberman think the key to their business’s success is that, by reusing old spaces and providing smaller, easier-to-maintain housing, they appeal to people’s desires for a simpler life. Rae says her renters and homebuyers “want to live a simple life that uses less energy.”

“They’re putting a lot into their jobs and their education trying to make it in this society,” Rae says. “They don’t want to be bothered with a large house, a large payment, a large anything.” As they move forward with their projects, Haberman and Rae rely on their own feelings and instincts — when they think something is cool, others seem to as well. “Pam and I recognized this trend within us,” Rae says. “We just said, ‘We’re tired of this. We want to move into somewhere small.’ That’s how we want to live. We don’t want to have to worry about a big place, a big this, a big that. And if we like it, we think other people will like it. We’ve been pretty lucky that way so far.”

Haberman says having a smaller home that costs less in terms of money and maintenance has benefits that extend beyond homeowners’ wallets. She sees living in a smaller home as the first step toward living a life that values relationships over things: “I think everybody’s just tired of the pace of their lives, of the amount of hours they have to work and of being tied to a big house. They have to spend a lot of money just putting stuff in it. It takes a lot of time to maintain it. It makes you a slave to your house, and your actual life goes away. Your kids are being cared for by someone else because you have to work so much to pay for your house.”

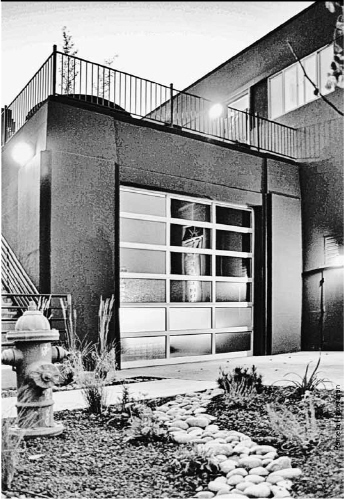

HabeRae rescued an abandoned 1950s firehouse in a dangerous part of the city. Now a 5,000-square-foot mixed-use building, the space offers a bagel shop, a salon and nine residential lofts.

The firehouse lofts include original concrete floors, custom glass mosaic tile work, sleeping lofts, high-efficiency heating and cooling systems and washers and dryers. A rooftop deck offers outdoor spaces with organic garden beds and drought-tolerant urban landscaping.

All the firehouse lofts include massive windows; residence 9’s roll-up wall of glass used to be the fire truck door.

Fighting the Good Fight

Fighting the Good Fight

Replicating the HabeRae model makes sense for landowners and renovators.

Landowners who consider reuse can save on building supplies, and salvaging architectural materials makes for a lower-cost overhaul. However, though reusing old buildings seems to benefit the community and the environment, HabeRae says they often find themselves fighting city hall rather than working with them.

Haberman laments a fight with city hall that she and Rae lost: “There was an old gospel mission in downtown Reno — a beautiful old building with Spanish tile floor, stucco arches. It was an old Spanish mission.” The duo had recently finished another renovation project, and she says, “We were hot to trot to do another old building.” They heard the mission was scheduled for demolition, so they tried to intervene. They called the real estate manager. “It took three or four phone calls, but finally someone gets back to us. We wanted to go look at it and they said, ‘Well, you have to wear a hardhat. It’s about ready to fall down,’ blah, blah. We went and looked, and in our minds, it was in great condition. It was a beautiful old historic building, and at the thought of tearing it down, we were like, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me!’” The owners of the property also owned several area casinos, and they planned to tear down the mission to build a parking lot. “We met with the city council and said, ‘Before you tear it down, let us take a shot at it,’” Haberman says. Though the city council said they would consider the offer, they ended up allowing the owner to demolish the old building. “Now, instead of this beautiful old building, we have a parking lot that’s almost always empty. They’re all about tearing down the old and making it new, but that’s so boring,” Haber-man states. “It’s like taking all the senior citizens out and shooting them! You would never do that. Their experience enriches everybody’s life. It’s the same with old buildings.”

Despite disappointments, HabeRae uses their projects as a tool to propel their city forward, and say others could do the same. “It starts with local government,” Rae explains. “We’ve really had to educate our community and the development section of the city of Reno.” She laments that often reuse seems to come with additional hurdles rather than aid: “It’s too bad there is no incentive to save old buildings. In fact, it’s the opposite. If you want to save an old building or get historical status, it’s going to cost you. You have to have a passion for it. You have to have intestinal fortitude. You can get discouraged, and, oh boy, you just want to go to a beach.” But Haberman and Rae have proven to the City of Reno that their developments work, and they’ve broken through many barriers with their innovative projects. “You have to show them examples. You can’t say, ‘Hey, I know everything, believe what I say,’” Rae says. “You have to show them a better way. You have to be the leader for change.”

And though changing minds in city hall is satisfying, changing homes and lives is HabeRae’s goal. “Life energy is precious, and we don’t want to spend our life energy on big houses and big yards,” Rae says. “We want to live a simple life. I think that’s important and brings a more social, communal country and community. I think that’s definitely lacking, and I hope we can change it.”