THE SOUND OF SILENCE

They gave us the soundtrack to our lives; then, in a flash, they were gone

PURPLE RAIN “The greatest gift was to see him onstage,” The New Yorker’s David Remnick wrote of Prince. “Live, emerging from the dry-ice clouds, he was unforgettable, unstoppable, a weather system all his own.”

The King

Elvis Presley

1935 — 1977

.png)

ELVIS ON TV Elvis Presley’s manager, Col. Tom Parker, left, Presley and Ed Sullivan, before Presley’s second appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. The television host paid Presley an unprecedented $50,000 for his three performances on the popular Sunday variety program.

Fans of Elvis Presley were used to a buzz of activity around Graceland, the King’s palatial home in Memphis, Tenn. But on Aug. 16, 1977, the sight of an ambulance driving through the crowd at Graceland’s gates suggested something far more ominous.

Presley, 42, had been discovered midafternoon that day in his bathroom, facedown, by his girlfriend, 20-year-old Ginger Alden. He was already cold when paramedics arrived. There were no vital signs. Still, Presley’s doctor—George Nichopoulos—insisted that the performer be brought to Baptist Memorial Hospital, 15 minutes farther than nearby Methodist South Hospital. At 3:30 p.m., an hour after Alden found him, the singer was pronounced dead. The death certificate stated that Presley had suffered a heart attack, but toxicology reports released later refuted that finding, revealing high levels of pharmaceuticals in his system.

During Presley’s childhood, such drug abuse would have been unimaginable. Presley was born in 1935 in Tupelo, Miss., to blue-collar parents. His formative years were spent surrounded by black musicians in his neighborhood, where he fell in love with rhythm and blues. After Presley’s family moved to Memphis in 1948, promoter Oscar Davis introduced the young singer to his associate, Col. Tom Parker, a former carnival huckster. Parker orchestrated the singer’s exit from Sun, the small label that gave Presley his first break, and brought him to RCA Victor. “Heartbreak Hotel” became his first No. 1 single for RCA in 1956, a breakthrough year that also yielded Presley’s first album, Elvis Presley, and movie contract (with Paramount), for the film Love Me Tender. A dizzying string of hits followed—Elvis would record 17 No. 1 and 38 Top 10 songs in his career—as he grew into rock’s most charismatic onstage presence. Presley appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show three times in 1956 and ’57—by his third performance, Sullivan and the network censors, concerned about conservative criticism of Elvis’s gyrating hips, decided to film the singer exclusively from the waist up. Presley’s initial performance was seen by 60 million viewers, or 83 percent of the television audience that night. The Beatles and the British Invasion pushed Presley out of the limelight for a time, but he resuscitated his career in the late ’60s by taking his act to Las Vegas.

What the public didn’t know—but his intimates did—was that Presley’s performance was fueled almost from the beginning by a steady diet of pills. Priscilla Presley, who met her future husband in 1959 when she was 14, reported in her memoir, Elvis and Me, that Presley relied on prescription medications from the time she first met him: Placidyl to get to sleep, then Dexedrine to wake up and prepare for the grueling schedule Parker demanded of his star client. Over the years, Presley needed larger quantities of pharmaceuticals to function professionally and cope with debilitating bouts of anxiety and depression. In 1973, after his divorce from Priscilla was finalized, he was hospitalized twice for drug-related issues, and he started canceling tour dates. By the time of his death, he was a mess, bloated to the point of obesity at over 300 pounds and, in addition to his drug addiction, was suffering from diabetes, glaucoma and constipation.

Medical examiner Jerry Francisco concluded that initial autopsy results indicated heart failure as the cause of Presley’s death. But the pathologist who conducted the autopsy disagreed, arguing that it was the combination and quantity of drugs in Presley’s body that killed him.

In 1980, Nichopoulos was charged with overprescribing drugs to Presley, rock legend Jerry Lee Lewis and several other patients. The trial brought a series of disturbing facts to light: Nichopoulos prescribed Presley more than 10,000 pills in the final seven months of the singer’s life; he borrowed almost $300,000 from Presley to finance a home purchase; and the doctor, often on tour with Presley in the later years, carried three suitcases filled with medications wherever Presley traveled.

Nevertheless, Nichopoulos was acquitted, based on his lawyer’s argument that Presley suffered from a long list of maladies, including arthritis and liver problems, that Nichopoulos was treating, keeping Presley alive longer than anyone could have expected. Furthermore, defense witnesses testified that the drug most detrimental to Presley’s health at the end was codeine, which Presley had gotten from a dentist and not from Nichopoulos. Despite the acquittal, the Tennessee Board of Medical Examiners took away Nichopoulos’s medical license in 1995 after finding that he was still overprescribing medications to his patients in the 1980s and ’90s; he died in 2016.

On the day after Presley’s death, the singer’s fans attended a showing of his body at Graceland, where a modest funeral, attended by former costar Ann-Margaret, soul legend James Brown and actor George Hamilton, was held in the home’s spacious music room. The following day, another 80,000 lined the processional route to Forest Hill Cemetery, where the King was buried next to his beloved mother, Gladys. Many of Presley’s fans refused to accept that he was really gone, believing against all evidence that Presley faked his death to relieve the pressure of a career he wanted to escape. Over the course of the following decades, people regularly reported seeing him in one bizarre location or another—boarding a flight to Buenos Aires, in a sc\ene in 1990’s Home Alone and, on his 82nd birthday, outside the gates of Graceland—but in truth the famous phrase that punctuated the end of his concerts had been uttered for the final time: “Elvis has left the building.”

FINAL YEARS On Jan. 14, 1973, Presley performed in Honolulu for an NBC special to be telecast in April.

Some four and a half years later, Elvis was dead and tens of thousands of people surged through the gates of Graceland to get a final glimpse of the King.

Strawberry Fields Forever

John Lennon

1940 — 1980

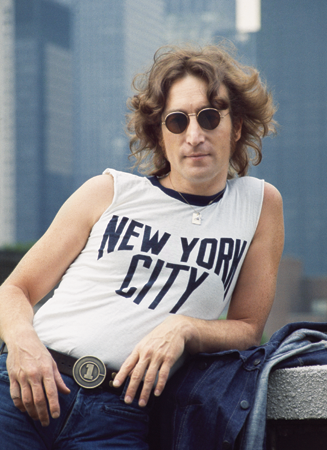

CITY FAVORITE “If I’d lived in Roman times, I’d have lived in Rome,” Lennon said after moving to New York City in 1971. “Today America is the Roman Empire, and New York is Rome itself.”

Mark David Chapman planned for weeks to kill John Lennon.

The troubled 25-year-old security guard had once revered the musician and as an adolescent had even wanted to become a Beatle. But over time, as his mind deteriorated and the demons took hold, worship transformed into obsession, then hatred. Chapman read The Catcher in the Rye, J.D. Salinger’s classic novel of teen angst, and began to identify with Holden Caulfield, the mixed-up hero who disdained phoniness. He hardened against his former idol: Lennon was a poseur, the sort Caulfield despised—a hypocrite who preached a life he did not lead. Chapman became convinced he had to bring Lennon down. He quit his job in Honolulu, signing out on the last day as John Lennon. He applied for a gun permit. He prayed to Satan for the strength to execute his scheme.

“Once the plan was in gear, I couldn’t stop,” Chapman later told journalist Jim Gaines. “Something in the back of my mind was going ‘Do it, do it, do it.’ ”

On Saturday, Dec. 6, 1980, Chapman flew to New York and checked in to a $16.50-a-night room at the YMCA close to the Dakota, the chateau-like co-op where the Lennon family lived. He loitered in front of the building, hoping to run into the singer, and on Monday the 8th, he finally did, when Lennon was heading to a recording session with his wife, Yoko Ono.

The encounter was almost routine. Chapman asked the singer to autograph Double Fantasy, the album he had just released with Ono. Lennon took his time, Chapman said later during a parole hearing. “He asked me if I wanted anything else . . . and that’s something I often reflect on, how decent he was to just a stranger.” Chapman, meanwhile, was delighted with the scrawl, gushing, “John Lennon signed my album. Nobody in Hawaii is going to believe me” to a Beatles fan he met on the sidewalk outside the Dakota.

Six hours later, when the Lennons returned, about 10:30 p.m., Yoko got out of the car first. As her husband followed, Chapman called out “Mr. Lennon!” then opened fire, hitting the musician four times in the back. Lennon staggered and collapsed in a pool of blood, and Yoko rushed to hold him. Amid the chaos, Chapman dropped the gun and sat quietly, thumbing through The Catcher in the Rye, which he had brought with him. When the police arrived minutes later, they handcuffed the shooter and moved Lennon, semiconscious and bleeding heavily, into a patrol car. By the time they reached Roosevelt Hospital, Lennon was already dead, but a team of seven doctors tried to resuscitate him anyway. When Dr. Stephan Lynn broke the news to Yoko, she was distraught and disbelieving, asking, “Are you saying he is sleeping?” Lynn later told Newsweek. Finally, at midnight, she returned home and called the three people she thought John would have wanted to know: Julian, his 17-year-old son from his first marriage; Mimi Smith, the aunt who raised him; and Paul McCartney.

As word of Lennon’s death spread, crowds gathered outside the Dakota, in Liverpool, in Stuttgart, Germany, in France and Japan. After two days of silence, Yoko released a statement describing the reaction of Sean, the couple’s 5-year-old son. “Now Daddy is part of God,” Sean told her. “I guess when you die you become much more bigger because you’re part of everything.”

Chapman was charged with second-degree murder and pleaded guilty. Now 62, he remains incarcerated in the Wende Correctional Facility in Alden, N.Y. He is eligible for parole every two years. On his ninth attempt, in 2016, the parole board told him, “We find that your release would be incompatible with the welfare of society.” He will be eligible again in 2018.

GRIEVOUS LOSS Producer David Geffen shielded a grief-stricken Ono as she left Roosevelt Hospital.

Photograph © Harry Benson 1980

Fans gathered in Central Park soon after his death to express their grief.

Mr. Soul

Marvin Gaye

1939 — 1984

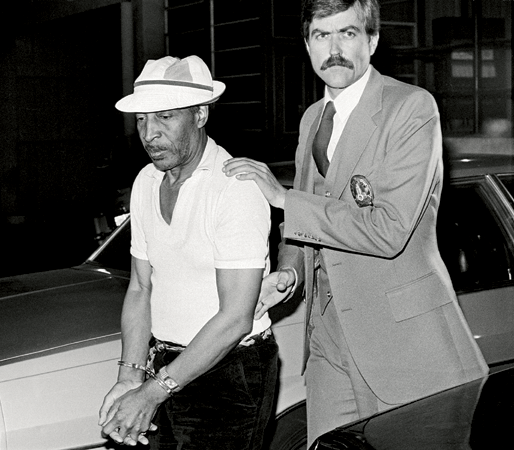

life and death Gaye (above) and his multi-octave voice produced 27 Top-20 hits. Soon after the shooting, a Los Angeles Police Department homicide detective led Marvin Sr. (below) into LAPD central headquarters at the Parker Center in Los Angeles.

It was the spring of 1984. Marvin Gaye, the soulful superstar behind “What’s Going On” and “Sexual Healing,” had moved back home with his parents in Los Angeles as his struggles with debt, drugs and depression became increasingly unmanageable. On the night of March 31, Gaye and his father, Marvin Sr., with whom he had a long-troubled relationship, began arguing as they often did over what Marvin perceived as Marvin Sr.’s mistreatment of his mother, Alberta. The fight continued through to the next morning and grew so violent—and physical—that Alberta had to intercede to separate the men. Marvin Sr. left the room, then returned with a Smith & Wesson .38 Special. He fired twice. The first shot entered the star’s chest, and as his son fell, Marvin Sr. fired a second blast at point-blank range. Less than 30 minutes later, Gaye was pronounced dead. It was April Fool’s Day, the eve of the singer’s 45th birthday.

No one who knew the family dynamics was entirely surprised. Since Marvin began performing at the age of 3, music had always been his escape from his alcoholic and abusive father. After Motown founder Berry Gordy discovered Gaye in 1962, he began churning out classic hits like “Can I Get a Witness” (1963), “Pride and Joy” (1963), “How Sweet It Is to Be Loved by You” (1964) and his first No. 1 hit for Motown, “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” (1968).

At the dawn of the ’70s, Gaye was a major star, but he was a troubled man. He chafed under the restrictions of the Motown machine and his unhappy marriage with Gordy’s sister Anna, whom he wed in 1963. Gaye persuaded Motown to give him creative control over his personal album Let’s Get It On (1971), but Gaye was tired of fighting, and his bouts of depression were becoming more frequent. In 1972 he moved to Los Angeles and began dating Janice Hunter, 18 years his junior. The couple wed in October 1977, but that marriage foundered, too, and ended in divorce in 1981.

Troubled relationships, a dependence on drugs, mental illness—some, including Hunter, believed that Gaye’s mood swings indicated that he was most likely bipolar—all combined to derail Gaye’s career. Even though his shift to CBS Records produced the critically acclaimed Midnight Love (1982), Gaye continued to spiral downward. Finally, with the Internal Revenue Service hounding him for back taxes, Gaye returned home.

In the end, there was no trial for Marvin Sr. After noting the injuries Gaye’s father suffered during the fight with his son, and considering the fact that Gaye’s autopsy revealed traces of cocaine and the dangerous stimulant PCP in his blood, the judge allowed Marvin Sr. to plead guilty to a lesser charge of voluntary manslaughter. He was given a six-year suspended sentence and five years’ probation. Alberta divorced him, and, broken and friendless, Marvin Sr. spent most of his remaining years until his death in 1998 in a nursing home.

“Marvin’s contradictions remain,” wrote biographer and friend David Ritz in 2008. “Discord and harmony echo through Marvin’s music like sweet incantations . . . He remains an astounding artist, an inspiring poet, a man whose fabulous talents and all-too-human flaws worked together for the sake of song.”

Reluctant Superstar

Kurt Cobain

1967 — 1994

FIGHTING FAME “It was so fast and explosive,” Cobain (in 1993) said of his success, in a generally upbeat interview in Rolling Stone just a few months before his death. “I didn’t know how to deal with it. If there was a Rock Star 101 course, I would have liked to take it.”

He was “the voice of a generation,” a designation he hated, who gave expression to his peers’ alienation, anger and inertia. He was the face of alternative rock. He was a musical genius. “I found it hard. It’s hard to find / Oh, well, whatever, never mind,” Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain sang with his usual blasé fatalism in “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” the hit that propelled him out of Seattle’s grunge scene and onto the world stage in 1991. “Here we are now,” he challenged the adult world. “Entertain us.”

From the time Cobain co-founded Nirvana in 1987, he moved people into a frenzy of love and anger. He was charismatic, charming and funny—until he would go in the corner and refuse to talk, which he did often. Three years after “Smells Like Teen Spirit” made him famous, Cobain was also, it seemed, beyond help. Clinically depressed since high school and a longtime heroin addict, he had overdosed multiple times. He saw countless doctors and therapists. His friends staged an intervention. He was in and out of rehab.

The last weeks of the singer’s life were particularly troubled. In early March 1994, he attempted suicide in Rome, then returned home to Seattle, where his relationship with his wife, the rocker Courtney Love, was deteriorating. A domestic dispute escalated, and when the police arrived, Love told them her husband had locked himself in a room with a .38-caliber revolver and was threatening to pull the trigger. At the end of the month, his manager and a group of friends and bandmates gathered in Cobain’s home with an intervention counselor. As part of the session, Love said she would leave him, and Nirvana said it would break up, unless the singer would check himself into rehab.

He did, flying to Los Angeles, where he spent two days in a 20-bed clinic before he told a staff member he was stepping out onto the patio for a smoke and then jumped over a brick wall undetected. For a week, Cobain could not be found. Love canceled his credit cards and hired a detective. His mother filed a missing person’s report. But neither would see Cobain alive again. On April 8, 1994, his body was discovered by an electrician, in a greenhouse above the garage of his Seattle home, the 20-gauge shotgun that the 27-year-old used to end his life across his chest. A high concentration of heroin and a small amount of diazepam were found in Cobain’s body. He had been dead for nearly three days.

The news was first reported on Seattle’s KXRX-FM after a co-worker of the electrician called the station. Even fans familiar with Cobain’s troubled life were disbelieving. When a public vigil was held on April 10, some 5,000 young people raged, grunge-rock style, at the injustice. They broke rank, leaping into a water fountain where the service was staged. As Nirvana’s “Serve the Servants” blared over the loudspeakers, fans were “plugging up the spigots, lifting their middle fingers to the skies, and howling with gleeful rage,” reported the music magazine Spin. Led by Love, they chanted a chorus of “F--- you, Kurt.” They burned their flannel shirts.

They were bereft, but said their goodbyes their way, just as Cobain did. “Thank you from the pit of my burning, nauseous stomach for your concern and your letters during the last years,” he wrote in his suicide note. “I don’t have the passion anymore, and so remember this . . . it’s better to burn out than to fade away.

“Peace, love, empathy.

“Kurt Cobain”

Fatal Flights

The “day the music died” and other infamous accidents

Glenn Miller

Glenn Miller and his orchestra

On Dec. 15, 1944, the swing-era bandleader was en route to France to organize a concert for troops in liberated Paris when his plane vanished from sight. Neither the aircraft nor its occupants were ever found, and the disappearance remains one of history’s great unsolved mysteries. Theories range from Royal Air Force friendly fire to Nazi subterfuge, but the most likely culprit was a faulty carburetor.

Buddy Holly

Buddy Holly's plane crashed into a cornfield in Clear Lake, Iowa.

Mechanical difficulties with a tour bus prompted rising rock star Holly, 22, to charter a plane from Mason City, Iowa, to Moorehead, Minn., on Feb. 3, 1959. Flying with Holly were the Big Bopper, 28, and 17-year-old Richie Valens. A few minutes after takeoff, the plane crashed, killing all on board. Singer songwriter Don McLean immortalized the accident as the “day the music died” in his 1971 hit song, “American Pie.”

Patsy Cline

On March 3, 1963, country singer Cline was in Kansas City, Kan., performing three benefit shows for the family of disc jockey “Cactus Jack” Call, who had died in an automobile crash on Jan. 25. Two days later, while returning home to Nashville, Tenn., Cline, 30, was killed when her small aircraft crashed into a forest outside Camden, Tenn., just 90 miles from Nashville. High winds and inclement weather were a factor.

Otis Redding Jr.

Otis Redding Jr.

Redding had just recorded what would become his biggest hit, “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay,” when he returned to touring with his band, the Bar-Kays. On Dec. 10, 1967, Redding’s plane took off from Cleveland for Madison, Wisc., in rain and fog, and four miles from its destination crashed into Lake Monona, killing Redding, the pilot, four members of the Bar-Kays ( Jimmy King, Phalon Jones, Ronnie Caldwell and Carl Cunningham) and their valet. Only trumpeter Ben Cauley survived; he died at the age of 67 in 2015.

Jim Croce

Jim Croce

Folk and rock singer Croce, 30, and five others were killed on Sept. 20, 1973, when their plane crashed into a tree while taking off from the Natchitoches Regional Airport in Louisiana, bound for Texas. Croce’s song “I Got a Name” was released soon after and went to No.10 on the singles charts.

Lynyrd Skynyrd

Steve Gaines (left) and Ronnie Van Zant of Lynyrd Skynyrd

After performing in Greenville, S.C., on Oct. 20, 1977, members of the southern rock band Lynyrd Skynyrd boarded a small plane for their next gig in Louisiana. When the plane started to have engine trouble, the pilot attempted an emergency landing, but crashed into a forest outside Gillsburg, Miss. Lead singer Ronnie Van Zant and lead guitarist Steve Gaines, backup singer Cassie Gaines (Steve’s older sister), assistant road manager Dean Kilpatrick, and pilots Walter McCreary and William Gray were killed on impact.

Ricky Nelson

It was the last day of 1985 when former teen rock idol Nelson, 45, was killed in a crash just two miles from a landing strip outside Dallas. Nelson, who came to fame in the 1950s and ’60s on his parents’ television show, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, was traveling with his companion, Helen Blair, four members of his band—Patrick Woodward, Rick Intveld, Andy Chapin, Bobby Neal—and manager Donald Clark Russell, all of whom died.

Stevie Ray Vaughn

In an eerie echo of the “day the music died,” blues guitarist Vaughn, 35, was killed in a helicopter crash on Aug. 27, 1990, after accepting a last-minute ride on a doomed aircraft. Vaughn had just finished two shows with Eric Clapton in Wisconsin, and grabbed the last seat on a helicopter instead of waiting for a later flight with his brother, Jimmie, to Chicago for the next stop on their tour. The pilot, his vision perhaps obscured by fog and low cloud cover, turned into a ski hill, and crashed 50 feet from the summit.

Aaliyah Dana Haughton

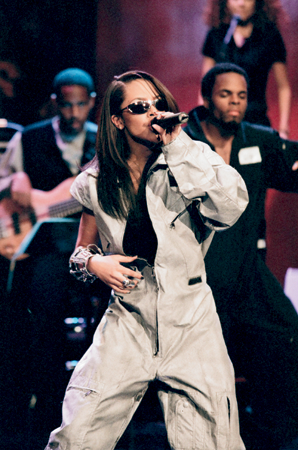

Aaliyah Dana Haughton

Aaliyah got a recording contract when she was just 12 and became an instant R&B star, but her success would be cut short. On Aug. 25, 2001, Aaliyah had just filmed a music video for her single “Rock the Boat,” when she and eight members of her entourage were killed in a plane crash shortly after taking off from the Bahamas. There were no survivors.

Tejano Trailblazer

Selena

1971 — 1995

GRIEF-STRICKEN The last two hits recorded by Selena (in 1995) were “Amor Prohibido” and “No Me Queda Mas,” the top-selling Latin singles of 1994 and 1995, respectively.

The scene was surreal. After shooting and killing Selena Quintanilla at a Days Inn in Corpus Christi, Tex., on March 31, 1995, Yolanda Saldívar, 32, the former head of the singer’s fan club, sat in a red pickup truck in the parking lot in a standoff with police. For almost 10 hours, Saldívar held a gun to her head, refusing to surrender, and as the day progressed, a crowd gathered across the street at a gas station to see what would happen. There were reporters, camera operators, onlookers and fans, some of them weeping, others playing Selena’s Tejano music on tape machines.

And then, at 9:30 p.m., Saldívar abruptly gave in and was rushed off in a patrol car. Abraham Quintanilla, the singer’s father, said Saldívar had been fired three weeks earlier from Selena, Etc., the family’s Corpus Christi boutique, because, he alleged, she had embezzled money; Selena had asked her to return financial documents. The two women agreed to meet at the Days Inn. “There have been discrepancies,” Quintanilla told reporters at the hospital where his daughter died, “and they resulted in her shooting Selena.”

It was a most improbable ending for the popular, telegenic singer, just two weeks shy of her 24th birthday. She had started singing with her father’s band at 3, and by her teenage years she was already a star, known as the Queen of Tejano, the blend of the oompah music of European settlers in Texas and Mexican ballads that she helped popularize. At the time of her death, Selena, who went by one name only, was often compared to Madonna but had a voice that was husky and sweet and a more wholesome image. She was also on the cusp of crossing over to a larger American audience and had placed five No. 1 singles on Billboard’s Hot Latin Tracks chart and scored a No. 1 debut album, Amor Prohibido, on Billboard’s Top Latin Albums chart. Wrote TIME: Selena “was the embodiment of young, smart, hip, Mexican-American youth, wearing midriff-baring bustiers and boasting of a tight-knit family and a down-to-earth personality—a Madonna without the controversy.”

In the hours after her death, a long procession of cars passed the lower-middle-class home where Selena had lived. Fans placed balloons and notes of condolence in a chain-link fence in front of her property. Bouquets of flowers piled up outside her boutique. In San Antonio, the capital of Tejano, fans organized two memorial services, one for each side of the city. As darkness fell, families, teens and grandparents waved candles, wept and swayed gently to Selena’s recordings. Thousands of callers jammed the lines at the state’s dozens of Tejano radio stations. For fans, it was “almost like the feeling when John Lennon died. She was the queen of Tejano,” Maria Aguirre, a receptionist at KQQK, a popular Tejano music station in Houston, told the New York Times.

In the years since the killing, Selena has retained her fan base and even attracted a new generation of followers. Saldívar remains in prison, where she is serving a life sentence. (She will be eligible for parole in 2025.) She has filed a string of unsuccessful appeals, arguing, among other things, that prosecutors coerced her confession and that she received ineffective legal counsel.

A fan wept beside a makeshift shrine to Selena outside her boutique in San Antonio.

The King of Pop

Michael Jackson

1958 — 2009

ELECTRIFYING Jackson teamed up with guitarist Slash of Guns N’ Roses for a 15-minute medley of Jackson’s greatest hits at the 1995 Video Music Awards in Los Angeles.

In the spring of 2009, anticipation for Michael Jackson’s “This Is It” comeback concert tour was running high. The 50-year-old King of Pop was rail thin, dogged by public scandals and financial woes, but he was still one of the most popular entertainers in the world, and his electric reputation and star power prevailed. The tour’s 50 dates sold out in a heartbeat, breaking several records. He stood to make as much as $1 billion. But the Gloved One never again performed before a live audience.

After a late-night rehearsal at the Staples Center in Los Angeles, on June 24, 2009, Jackson returned to his home, but, as always, had trouble getting to sleep. Just before 11 a.m. on June 25, he was discovered unresponsive by his doctor, Conrad Murray, a cardiologist hired by Jackson as his personal physician. His pulse was weak and his body still warm. Murray administered CPR, but was unable to revive his patient. More than 30 minutes passed before emergency personnel arrived.

Jackson was pronounced dead at 2:26 p.m. at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center. Doctors determined that he had suffered a fatal heart attack caused by an accidental drug overdose of tranquilizers and propofol, a medication generally used to relax patients before and during anesthesia. Combining it with alcohol and other medications is considered dangerous. The 5-foot-9 performer weighed just 136 pounds.

After the coroner’s autopsy, Jackson’s death was ruled a homicide. Murray, who admitted giving the singer a series of drugs on the day of his death between 1:30 p.m. and 10:40 a.m.—Valium (an anti-anxiety drug), Ativan (a tranquilizer), Versed (a sedative), Ativan again, Versed again and finally 25 mg of propofol—was charged and convicted of involuntary manslaughter. He would ultimately serve two years of a four-year sentence. As of 2016, he was living in Florida, stripped of his medical license, and trying to put his life “back on track,” he told CNN’s Don Lemon in an interview.

For Jackson, a child Motown phenomenon who grew into a moonwalking megastar, the beginning of the end was Jan. 27, 1984. That was the day he suffered third-degree burns on his scalp while filming a Pepsi commercial. According to the book 83 Minutes: The Doctor, the Damage, and the Shocking Death of Michael Jackson, the singer was in such pain that he took Percocet, Darvocet and, during his subsequent scalp treatments, large amounts of Demerol, all of which kick-started decades of dependence. In addition, he suffered from severe insomnia, and at the time of his heart attack, had gone about two months without REM—rapid eye movement—sleep, which is vital to keep the brain and body alive. Instead, he had taken nightly infusions of propofol, administered by Murray.

By the time he died, Jackson was exhibiting classic signs of propofol abuse. According to testimony from his chef, hairstylist and choreographers at the wrongful-death trial of concert promoter AEG Live, Jackson was unable to do standard dances or remember words to songs he’d sung for decades, suffered from paranoia and severe weight loss, talked to himself and was apparently hearing voices.

Jackson’s death set off a media and fan frenzy. Impromptu vigils broke out around the world, from Portland, Ore., where fans organized a one-gloved bike ride (“glittery costumes strongly encouraged”), to Hong Kong, where fans gathered with candles and sang his songs.

In Los Angeles, hundreds clogged the streets in the Westwood neighborhood around the UCLA hospital. Some danced and played Jackson’s music, as a helicopter flew away with his body, en route to the coroner. Radio stations everywhere cued up his songs. More than 1.6 million people applied for the 17,000 tickets available for his memorial service at the Staples Center, which was watched via live streaming by reportedly more than 1 billion worldwide.

“On the one hand, it’s shocking,” music journalist Alan Light, told the Washington Post. “On the other, everybody had the sense that there was not going to be a happy ending to this story. I don’t know what other final chapter there was going to be . . . It’s almost impossible to overstate the impact he had on popular music and popular culture. He was the ultimate crossover figure, bringing black music and rock and roll together.”

In the year following Jackson’s death, fans rushed to buy his music. More than 35 million albums were sold worldwide, and combined sales for three of them—Thriller, Number Ones and The Essential Michael Jackson—topped any new release that year. A documentary, This Is It, about Jackson’s preparation for the tour that never was, hit theaters four months after his death and drew critical praise despite complaints that it exploited the singer’s demise. It also drew lots of fans and was the most successful concert film and documentary of all time worldwide, grossing $261 million.

END OF A LEGEND In 1969, the Jackson Five (from left, Tito, Marlon, Jackie, Jermaine and Michael) released their debut album, Diana Ross Presents the Jackson 5.

Two days before his death, Jackson rehearsed for his upcoming concert tour.

Fans gathered outside the Apollo Theater in Harlem five days after his death for a tribute to the star.

The Thin White Duke

David Bowie

1947 — 2016

MAN OF MANY FACES Bowie’s personas included the glam rocker Ziggy Stardust (above) in the 1970s. The video for “Lazarus” (following photo) suggested to fans that the star was aware of his impending death.

In 2015, only a small circle of family and friends were aware that David Bowie was suffering from liver cancer. But the rock legend managed his schedule carefully to conserve his energy, working on a new album and contemplating new projects. So when the disease took his life on Jan. 10, 2016, just two days after his 69th birthday, many of the star’s friends and fellow musicians were as shocked as the public at large.

Looking back, the secrecy was hardly surprising. Even during his attention-grabbing gender-bending glam rock period in the 1970s, Bowie had had an uneasy relationship with fame, and as he grew older, he had largely withdrawn from the spotlight, eventually settling in New York City, where he felt he had the best chance to live in relative anonymity.

A restless intellectual, Bowie experimented with a shifting constellation of personas and musical styles, including glam rock, electronic music, funk/soul, jazz and sometimes a mash-up of all of them. His success, with hits like “Ziggy Stardust,” “Young Americans,” “Heroes,” “Rebel Rebel” and “Changes” spoke to Bowie’s position as one of rock’s most innovative artists.

He was diagnosed with cancer in mid-2014 while working on his final album, Blackstar, a recording that was released on his birthday and continues to be scrutinized by fans for signs that he knew of his impending death. The song “Lazarus,” which includes the lyrics, “Look up here / I’m in heaven / I’ve got scars that can’t be seen,” may be the most obvious premonition, and the song’s video opens with a blindfolded Bowie in a hospital bed.

The song was likely more prescient than confessional. The video’s director, Johan Renck, told the BBC that “Lazarus” was written before Bowie learned that his illness had become terminal. Still, the singer was aware of the cancer throughout the Blackstar’s production, and it’s hard to listen to it without hearing a certain elegiac tone. Tony Visconti, Bowie’s longtime producer, described Blackstar as Bowie’s “parting gift. I knew for a year that this was the way it would be. I wasn’t, however, prepared for it.”

In the days after his passing, tributes from fellow musicians poured in, and fans constructed makeshift memorials outside his previous homes in London and Berlin, as well as his last home, in New York City’s Soho district. Lady Gaga performed a medley of his hits at the 2016 Grammy Awards and Lorde—the young singer from New Zealand whom Bowie saw as the future of popular music—performed a moving rendition of Bowie’s “Life on Mars?” with members of his band at the Brit Awards in London six weeks after his death. Madonna may have offered the pithiest epitaph for an artist she deeply admired: “Talented. Unique. Genius. Game Changer.”

The Purple One

Prince

1958 — 2016

BRIGHT CANDLE “Life is just a party,” Prince (circa 1970) said, “and parties weren’t meant to last.”

It was just beginning to drizzle when Prince and his band took the stage for their halftime show at the 2007 Super Bowl in Miami. A capacity crowd of 75,000 watched live and another 140 million tuned in from home as Prince and his backup singers, in high heels as always, navigated the slippery stage. With the exposed electrical cords and sound equipment littering the stage, the producers worried the platform was a minefield, but Prince dismissed their concerns, asking, “Can you make it rain harder?” By the time the set reached its crescendo with Prince’s megahit “Purple Rain,” the real rain was pouring down in sheets, adding yet more drama as the band drove to its finish. The crowd responded with an extended standing ovation.

The performance was quintessential Prince. The singer had been thrilling audiences for decades, dropping into splits and bouncing back to his feet, sliding across the stage and leaping off risers in platform heels. Few performers in rock history were as willing as Prince to sacrifice their bodies. But over time, the acrobatics took a toll on the singer’s 5-foot-3 frame. His hip issues first surfaced in 2005; four years later, he was relying on painkillers to manage his symptoms, and when a hip replacement in 2010 failed to eliminate his pain, opioids seemed the only answer. By 2016, the private star was suffering from decades of wear and tear. His hips, his ankles, his back—they all hurt, and the pain was chronic.

In early April 2016, Prince canceled a scheduled concert in Atlanta, the first sign that something was wrong. When he walked onstage for the makeup event on April 14, he apologized for missing the earlier date, joking with a slight smile about being “under the weather,” but, in retrospect, the concert offered hints of his condition. Though his voice sounded strong, he sat at the piano for almost the entire 80-minute show—in his prime he might perform for nearly four hours—standing only occasionally to pound the keys and walk around the piano before settling back into his seat. When, on the flight home to Minnesota, Prince became “briefly unresponsive,” his private plane made an unscheduled landing in Illinois and he was treated in a local emergency room. “Just wait a few days before saying your prayers,” Prince assured alarmed fans shortly afterward at his Paisley Park estate in Chanhassen, Minn. While his spokespeople insisted he was dealing with the flu, Prince had his representatives reach out to California pain specialist Dr. Howard Kornfeld on April 20. Kornfeld agreed to meet the singer on April 22. That meeting never took place.

On April 21, Prince was found dead in an elevator at his home by Kornfeld’s son, Andrew, and two staff members. Emergency personnel estimated he had died six hours earlier. An autopsy determined that the performer accidentally overdosed on fentanyl, a synthetic pain medication similar to morphine but far more potent. An investigation remains open on whether Prince acquired the fentanyl legally.

Prince’s death was met with anguish. Fans flocked to Paisley Park and went on a buying spree of his music. Posthumously, Prince set a new Billboard record, with five albums appearing concurrently in the Top 10. Many prominent locations, including Target Field and the I-35 Bridge in Minneapolis, Niagara Falls in New York, Los Angeles City Hall and the Superdome in New Orleans (but not, as some believe, the White House), were lit in varying shades of violet in honor of the singer’s most iconic album, Purple Rain. The U.S. Senate recognized the singer as a “cultural icon.”

Prince’s remains were cremated following his autopsy and placed in a ceramic and glass 14- by 18-inch scale-model of Paisley Park. It is currrently on display at Paisley Park, which opened to the public in October 2016. With no will in force, his estate has generated a raft of litigation. In May 2017, a judge in Minnesota who had whittled down the list of 29 people laying claim to Prince’s estate, declared his six siblings—his sister Tyka Nelson and five half-siblings—to be the legal heirs to his fortune estimated to be worth $200 million. But issues remain, including appeals by the rejected would-be heirs, a lawsuit filed by the estate against Prince’s former advisers and the difficulty in finding an acceptable administrator for the estate.

LAST CALL There were no gymnastics during Prince’s final concert in Atlanta, but one observer described the spare, stripped-down show as “more like a church service than a concert.”

Fans scrawled their tributes to their idol on a T-shirt outside the Apollo Theater in Manhattan.

Rock’s Horrible Year

A trio of legends, all 27, perished in just 10 months

Jimi Hendrix

The Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones (left) and Jimi Hendrix in 1969. Jones drowned 14 months before Hendrix’s overdose.

By the fall of 1970, Jimi Hendrix, described by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as “arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of rock,” was exhausted, worn down by constant touring and insomnia. He was also facing a paternity suit, feuding in court with his record company, and juggling several girlfriends. Hendrix’s band, which played a freeform improvisational style called psychedelic rock, was also in crisis—bass player Billy Cox had announced he was leaving the group, jeopardizing Hendrix’s upcoming tour. He spent much of his last two days, Sept. 16 and 17, in an apartment in London’s Samarkand Hotel with his sometimes girlfriend, figure skater and painter Monika Dannemann. The pair had several arguments, the last taking place at a late-night party at the home of Hendrix's business associate Pete Kameron. After considerable drama—Dannemann was initially refused admission to the party—the couple returned to Dannemann’s apartment about 3 a.m. Over the years, Dannemann would alter her story multiple times. Initially, she claimed that she woke around 10 a.m. to find the singer sleeping normally, went out to buy cigarettes and discovered Hendrix unconscious but breathing when she returned about 11 a.m. She also said that she called an ambulance, was present during the EMTs’ futile attempts to revive him and rode with Hendrix in the ambulance to St. Mary Abbot’s Hospital, where he was pronounced dead. But the EMTs contradicted that account, claiming that when they arrived at the Samarkand, Dannemann’s door was open and her apartment empty, except for Hendrix’s lifeless body on the bed. Dannemann was nowhere to be found and the emergency workers said they took Hendrix to the hospital themselves. The autopsy concluded that Hendrix had choked on his own vomit as a result of a barbiturate overdose. Dannemann later said that she determined that Hendrix had taken nine of her Vesparax sleeping pills, some 18 times the recommended dosage. Had Hendrix committed suicide? Officials stated that there was not enough evidence to support that conclusion and Dannemann vehemently denied it, arguing that in his desperate desire for sleep, Hendrix had taken the lethal dose in error.

Janis Joplin

Janis Joplin

Rock fans were still reeling from Hendrix’s death when Janis Joplin overdosed on heroin 16 days later, on Oct. 4. Known for her hard-living lifestyle, the singer who made “Piece of My Heart” and “Me and Bobby McGee” was known to shoot heroin, toss down methamphetamines and imbibe vast quantities of her favorite drink, Southern Comfort. On Oct. 3, Joplin and her band held a late-night recording session, and then she went out to a local bar with organist Ken Pearson. The next day, when Joplin failed to show up at the studio, road manager John Cooke went to the Landmark Motor Hotel in Hollywood where she was staying, persuaded the manager to open the door and found the singer dead on the floor beside her bed. There were fresh needle marks in her left arm.

Joplin’s death was ruled an accidental heroin overdose possibly exacerbated by alcohol. Her friends believed she did not want to die and unknowingly injected herself with a potent form of heroin, since several of her dealer’s other clients also overdosed during the same week. Her obituary in the New York Times ended with the quote: “Maybe I won’t last as long as other singers, but I think you can destroy your now worrying about tomorrow.”

Jim Morrison

Jim Morrison

Heroin was also suspected in the death of the Doors’ lead singer, Jim Morrison, in Paris the following July, though the official ruling was that he died of a heart attack. Discovered in his bathtub by girlfriend Pamela Courson, Morrison was buried three days later in the Père Lachaise cemetery without a formal autopsy, since there was ostensibly no foul play involved. In the intervening years, conspiracy theories have flourished. Some believe that Morrison suffered his heart attack after snorting some of Courson’s heroin, thinking it was cocaine, Morrison’s drug of choice. According to that theory, Courson, whose story changed before she died in 1974, panicked, ran for help, and put Morrison in a bathtub of warm water, which sometimes works as an antidote for a heroin overdose. Former New York Times writer and club manager Sam Bernett advanced an alternate story, one in which he found a lifeless Morrison in a bathroom stall in a nearby nightclub, Rock ’n’ Roll Circus, and drug dealers transported the singer’s body back to Morrison’s apartment to avoid being implicated in his death.

In The End: Jim Morrison, Bernett wrote: “The flamboyant singer of the Doors, the beautiful California boy, had become an inert lump crumpled in the toilet of a nightclub.” Singer Marianne Faithfull, in a 2014 interview, said that her then-boyfriend, Jean de Breteuil, had supplied Morrison with heroin that night. As with Elvis Presley, some of Morrison’s fans prefer to believe that Morrison faked his death to escape his celebrity.