5

FOR ALL THE TIME I have spent researching the recovery and identification of missing persons—first in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and now in the United States—I still struggle with one particular act: contacting surviving families to ask them about their lives and about their missing loved ones. However I might justify it with grander aims of understanding the experiences of those most intimately connected to the processes of caring for war dead, the request is an intrusion. It comes from a stranger, who asks to tread upon a realm of memory and emotion that is quite private and, for many, still raw, no matter how many years have passed since the news of loss or disappearance. Sometimes, the request is met with wariness, sometimes with polite but tacit refusal. More often than not, I have benefited from the generosity of families who, without knowing exactly what anthropology is or ethnographic research entails, have answered yes.

Their stories inform my exploration of “homecomings,” when identified remains are finally returned to their surviving kin. In these homecomings, we see yet another side of exceptional care, a more localized, private version than the pageantry on the tarmac in Đà Nẵng or the celebration of First Lieutenant Michael J. Blassie’s identification presented in the Memorial Room at the Tomb of the Unknowns. Not that the nation is absent or these homecomings don’t involve military rituals of remembrance. They do. But homecomings expose the layers of grief sedimented in the lives of those left to contend with uncertain loss for decades on end; they also evoke forms of commemoration that have as much to do with a local “home,” defined by family and community, as with the patria to which the remains have been returned. Finally, through these stories of homecoming, we see how even the tiniest fraction of a body, located, identified, and returned through the myriad labors of accounting, can do the magical, powerful work, in Laqueur’s words, of settling safely the missing in action or killed in action / body not recovered into memory and into a proper place of posthumous belonging.1

Dwayne Spinler was one of the MIA family members who shared his experiences and memories with me. Son of an air force pilot shot down in 1967, Dwayne was just five years old when his father, Captain Darrell John Spinler (the same Capt. Spinler of REFNO 0738 in Chapter 2), left for the war. His last memory of his dad is riding in the car with him to the airport. Dwayne cried the whole way there and the whole way back because he was scared that his father wouldn’t come home.

“And he didn’t.”

Dwayne and his wife, Dawn, were among the families who came to JPAC in 2011 to take custody of identified remains and escort them home. I accompanied them as they toured the facility and watched as they stepped into the family visitation room to behold all that now remained of Dwayne’s father—three scant teeth, bluish in color, a rusted pocket knife, and a pair of nail clippers. I also looked on when, earlier in the visit, he spoke with Marin Pilloud, the anthropologist who had helped recover his father’s remains. This too was an intrusion of sorts, or so it felt to me as part of the small group of JPAC staff who stood nearby as their conversation unfolded. Its intensity had filled the hall outside the forensic anthropology examination room.

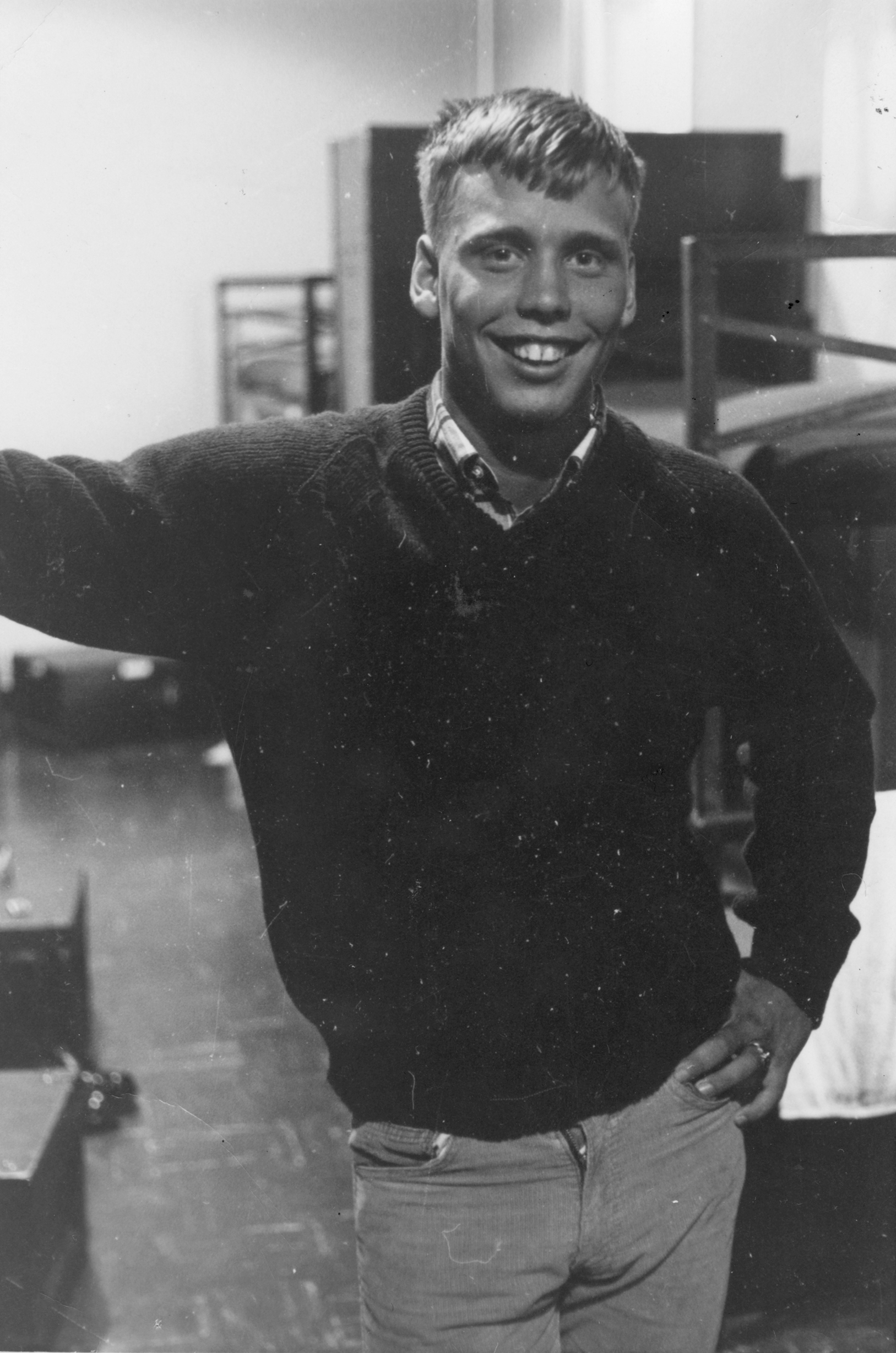

Dwayne is a tall, sturdy-looking man. As I would learn later, he takes after his father, who at six feet four was strikingly handsome, with broad shoulders and chiseled jaw. Dwayne explained that in flight training school, his father was “almost too tall to qualify, because there was a concern that he wouldn’t fit in the cockpit.” Perhaps that frame, the son’s physical stature, was what made the next few moments so arresting. As Marin was wrapping up, having given the tour and talked briefly about the recovery mission she and veteran archaeologist Greg Fox had directed at his father’s crash site, Dwayne asked if he could hug Marin. He leaned down—he was much taller than she—and as they embraced, he began to cry, at first softly and then his whole frame shook with muffled sobs. Marin’s eyes filled with tears as he whispered to her “thank you” over and over. As she explained to me later, she was twelve weeks pregnant with her own son at the time and felt Dwayne’s loss all the more keenly for it. The rest of us stood transfixed and silent, as if even a shift in weight would pierce the bubble of solace that had enveloped them.

Captain Darrell John Spinler with his wife, Darlene.

When he stepped away, Dwayne once more thanked her for finding his father.

As I would with several of the cases I researched at the laboratory, I followed Capt. Spinler’s story of homecoming from afar. Newspaper coverage helped sketch a portrait of his momentous return:

Now tiny Browns Valley, population 600, expects to double its size for a day this month, when Darrell Spinler’s remains return home for a full military funeral.

Spinler’s parents have since passed away, and no close relatives remain in Browns Valley. But the town, a farming community in Traverse County on the border with South Dakota, is bracing to accept a long lost hero back home.

“We’ve just been trying to do what we can. If we get 600 visitors, it could make a real mess in town. We’re just trying to coordinate traffic control and making sure everybody’s got a place to go,” said Jeff Cadwell, the city administrator.2

Dwayne himself went on to publish an essay online recounting his family’s experience. In “Bringing Dad Home,” he chronicled the various events—from the first phone call he received to his father’s burial in Browns Valley—interspersing his reflections with photographs of the journey, its way-stops, and the people who gathered to welcome his father home. A modest work on the surface, it encapsulates the experience of MIA accounting from a family member’s perspective. Among other things, Dwayne Spinler concludes, “family is not limited by genetics or marriage. You can find family anywhere.”3 Marin was part of that expanding, if ephemeral, web of familial ties. “When I first learned who she was,” he wrote, “I remember wanting to reach out and touch her arm, this person I did not know, so intimately linked to my father.”4

While the notion of kinship forged through the return of remains arose repeatedly in the course of my fieldwork with MIA families, Dwayne’s essay—alongside the poignant encounter between him and the anthropologist who “found” his father—crystallized the unique memory work that advances in forensic science have enabled. But to understand fully that work requires an intrusion into the most personal of recollections—those associated with someone loved and lost. Would Dwayne be willing to speak with me about his father’s life, his loss, the years of ambiguity, and finally that homecoming to Browns Valley, Minnesota? Would he be willing to allow an outsider access to those memories?

And so, six years after watching Dwayne come to the lab to receive his father’s remains, I sent him a letter: “Dear Mr. Spinler, I hope you won’t mind me reaching out to you.”

EARLIER I ARGUED THAT MIA HOMECOMINGS, though the celebrated endpoints in the longer journey of recovery and identification, necessarily have their beginnings. So too they have their middles, the time in between, a time of survival and endurance. I am speaking here not of the missing in action, but rather the parents, spouses, and children left behind. For those families who await news of their loved one, ambiguity and uncertainty disturb memories and color imaginings with shades of confusion, hope, grief, anger, and fear. Dwayne Spinler’s outpouring of sorrow, I soon came to learn, grew out of that “time in between” as much as it did from the unexpected return of his father’s remains. This was one of the lessons I learned when we finally spoke—one that the narrative of exceptional care often sidesteps—namely, the profound imprint that prolonged and ambiguous absence leaves on those who wait and wonder about the “what ifs” of their loved one’s fate and their own life’s course. A couple of weeks after I sent it, Dwayne answered my letter, and not long afterward, he told me about his life after his father’s death and before the return of his remains.

As is the case for many of the MIA children I’ve spoken with, when he lost his father, Dwayne lost a piece of his innocence. But he was also burdened with a responsibility of care few young children ever come to know. On the day of the “initial” funeral service in 1967, when relatives gathered to mourn Captain Darrell John Spinler’s loss, a close family friend, one of his father’s mentors from the air force, instructed Dwayne to take up that burden:

When I was a kid I remember him very clearly telling me this. I think it was at the initial funeral, ‘cause they didn’t find any of my dad’s remains at that time. This was up in Minnesota. I actually have some newspaper clippings of a picture of my dad’s father, my grandfather, my mom, me, and my brother, as they were giving my mother either the flag or purple heart or something like that. And I remember Colonel Tudor telling me “Ok, you got to be the man of the house, you got to take care of your mom,” and, you know, my dad died when I was like six and a half years old. And I’m sure his intentions were good, but, you know, for me, as a kid—it’s no mistake I got into the mental health field as a profession—that he didn’t know how seriously I took that. And for me, I didn’t tell anybody, I had nobody really to talk to, and I kind of assumed, ok, because my mom really struggled with my dad’s death for many years. Which eventually turned into depression, then she was on medication. Her first suicide attempt was when I was eight.5

At the time, Dwayne didn’t know the full story. The adults in his world decided it would be better to shield him, to tell him that she had slipped in the bathroom and hit her head against the sink. But even then, he recalled, “it still didn’t feel like they were telling me the truth.” Years later, hospitalized once again for attempting to take her life, his mother acknowledged what had happened on that first occasion. If her admission shed light on a confusing, troubling episode from his childhood, it also underscored what Dwayne had long witnessed firsthand—his mother’s daily battle to survive her husband’s loss. Her emotional fragility introduced another layer of precarity into his life. “As a young kid, I had the sense that, well, Dad’s gone, he got killed in the war, and I’d seen Mom struggling with her sorrow and grieving and it turned into depression, and I think, well, I got to take care of Mom, because if something happens to Mom, what’s going to happen to me?” In her bereavement she sought comfort in private rituals of remembrance, ones that Dwayne took care not to trespass. “There would be times,” he explained, “where she’d pull out this suitcase that would be in storage which would have a lot of the letters that my mom and dad would send back and forth when he was in Vietnam. I never read a single one for a reason. It’s like it’s not my business. That was between my dad and my mom. And you know that would contribute to her feeling sorrowful and sad.”

Then early one morning, when Dwayne was in graduate school, he got a call from his father’s mentor, Colonel Tudor.

I thought, who the hell is calling me at 8 o’clock on a Monday? And I just had this gut feeling, and it’s like, well, it’s probably not good news. And it was Colonel Tudor on the phone. And he said, “Dwayne, this is Colonel Tudor, and I don’t know how to tell you this other than to just tell you, but your mom has committed suicide the previous night.” She had been drinking alcohol, and took an overdose of medications, and on top of that she was in her car in the condo garage with a hose attached to the exhaust pipe, so asphyxiation. And my half-sister, who’s like eleven years younger than I, she was asleep in the condo, down in her basement bedroom, and fortunately my mom turned the ignition off on the car. Otherwise the fumes probably would have killed my half-sister too. So my half-sister found her and called the police.

Grief has a way of churning up guilt, warranted or self-imposed, forcing it to the surface of even the stillest waters. When Dwayne spoke to me about his mother’s struggles with depression, he did so alternately as a son and a professional counselor, recounting his own frustrated attempts to support her through the tools of mental health care he himself was in the process of learning at the time. “What was hard for me was for a lot of the years my mom was alive, she’d call me up, I’d be in school, college, undergraduate or graduate school, she’d be sad, depressed, sometimes intoxicated, and I’d talk her down. My mom wasn’t a bad person, she just had a bad illness, and she never got over my dad’s death.” Without him, without even the solace of his returned remains, Dwayne’s mother suffered, and there was little Dwayne could do to lessen that suffering, try as he might, including through one final, touching gesture to comfort his mother by honoring his father.

About a week before the call I got from Colonel Tudor saying that she had committed suicide, I had had a conversation with my mom, to let her know that I was about to be a father and that my girlfriend, we were going to get married, and we already knew the sex of the baby. It was going to be a boy. And I told my mom that we were going to name him after my father. And it was met with about fifteen seconds of just silence on the other end of the phone. And I’m just thinking, “Oh crap, this is going to upset her or something.”

My mom never got to meet my son. She died before he was born. A week after was when she committed suicide. And so I struggled with feelings of guilt. You know, here I am studying this profession, and I’ve talked her down numerous times on the phone, and it’s like I’m a graduate student, I’m not an expert in this field, I’m trying to become an expert. But it felt like I had failed my job.

Eventually I came to the realization that I didn’t cause my mom’s suicide. I didn’t do it to her. She didn’t do it to me.… She did it to herself, and it hurt. It was a really sad situation.

As his mother’s unabated, and ultimately debilitating, grief brought an end to her life, it also predominated Dwayne’s “in between,” stretching across his childhood and adolescence and inflecting his relationships in marriage and fatherhood, well after her death in 1985. And then he got a call out of the blue in February 2011, forty-four years after the news of his father’s air crash. Captain Darrell John Spinler—the three teeth Marin and the JPAC team excavated on the bank of the Xe Kong River in Laos—had been accounted for, and Dwayne would serve as the special escort to shepherd those tiny fragments back to Browns Valley to be buried alongside his father’s parents, grandparents, and grief-stricken wife.

One of the striking features of his essay, “Bringing Dad Home,” is Dwayne’s attentiveness to those around him and the spontaneous acts of remembrance his father’s remains spurred. Though he insists that “you can find family anywhere,” a particular kind of familial bond—that born of military service—stands out among the myriad encounters he chronicles along the journey from Hawaii to Browns Valley. On one of the flights, he spotted a man with a Vietnam Veterans baseball cap, and, after the pilot announced that Dwayne and his wife were escorting his father’s remains home (to the applause of fellow passengers), Dwayne got out of his seat and approached the veteran. He wanted to thank him for his service. “I knelt down on one knee and we shared a firm handshake while exchanging mutual heartfelt tears together.” In his work, Dwayne has counseled numerous veterans. “I have always recognized the unique pain seen in the eyes of a veteran.” He and the older man “shared a moment” and then he returned to his seat. A few minutes later, the man reached up to his overhead bag, removed his Vietnam Veterans cap, and walked down the aisle toward Dwayne and his wife. Tearing up again, the man asked, “Would you place this in the casket for me on behalf of all our Vietnam brothers?” Dwayne told him he would be honored to do so.6 The gift of a seemingly mundane article—a baseball cap—from a total stranger—a man Dwayne had never met before and would likely never see again—would come to rest in that most sacred of spaces: the coffin. It would lie nested next to the full Class A uniform, meticulously ironed and fixed with medals earned in war, and atop the traditional wool blanket, itself pinned securely around three teeth. Having been plucked from the banks of a river halfway around the globe, those tiny remnants of a human life, along with the cap, the uniform, an MIA bracelet worn in remembrance, and the bundle of letters that Dwayne never read, the ones exchanged by his mother and father while the war raged on, would all be lowered into the hollowed-out plot of a cemetery in a small town on the border between Minnesota and South Dakota.

Family and friends assembled at Captain Darrell Spinler’s graveside, including Dwayne (center, dark suit), his brother David (to his right), wife Dawn (to his left), and son Darrell John (behind him).

IF DWAYNE SPINLER TAUGHT me about the knotted grief that can grow in the spaces and years between loss and homecoming for MIA families, Jeff Savelkoul helped me understand what MIA absence might mean for a veteran. Their experiences likewise affirmed the powerful event of a homecoming, when the living and the dead become entwined in a project of national belonging that nevertheless unfolds according to local traditions of remembrance and recalling specific histories of loss. They also helped me appreciate how such remains could invite new configurations of family, when kith and kin and strangers alike convene to remember not just a distant war, but a life lost and, decades later, returned to a particular community of mourners.

A survivor of the CH-46 helicopter crash that killed radio operator Lance Corporal Merlin Raye Allen, Jeff Savelkoul came back to the United States in 1967 a physically scarred man with a battered, broken, and burned body—to say nothing of a psyche that in the aftermath of the fiery crash on the mountain slope also had to absorb the fact of his best friend’s death. That fact eventually brought him to the driveway, the top of the gravel lane, of the Allen family property in Bayfield, Wisconsin. He felt he had to visit them but feared their reaction, especially to his physical appearance; a significant portion of his ears had been burned off when the rear fuel tank was struck and flames had shot through helicopter. “If I looked this bad, what would they think their son endured? I made four trips from Minneapolis to Bayfield—a four-hour trip. I’d get there and turn around at the end of the Allens’ driveway and go back home. I just couldn’t face them. Finally, after sixteen years and four tries, I got up the courage and walked up to the house. It turned out to be one of the greatest things I’ve ever done in my life.”7

Merl’s mother, Eleanor, opened the door. She was taken aback, but not for the reasons Savelkoul had feared. Rather, his story defied everything she and her husband knew of the helicopter crash that killed their son. They had been told by the military that no one had survived. And yet there at their doorstep stood this stranger, claiming not only to have known their son, but to have served with him in Vietnam and to have survived the very same crash. To hear Jeff and Merl’s sister, Marilyn, tell it, Skip Allen, Merl’s father, didn’t believe a word of it. He was immediately suspicious of Jeff’s claims. Not until Marilyn arrived—her husband Ralph was on the Bayfield police force, and the Allens called him to tell Marilyn to rush home—did the truth begin to sink in. Marilyn knew of Jeff from her brother’s letters home and had even exchanged letters with Jeff herself. He was who he said he was, a member of Team Striker, and Merl’s best friend during the months of war they lived through and waged in 1967.

From that day forward, Jeff became a part of the Allen family, growing close to Merl’s parents and five siblings, especially his brothers, Casey and Sean Allen. They’d go hunting and fishing together, and over time, Jeff shared details about Vietnam and about the helicopter crash. For Sean, who was twenty-two years old when they met, Jeff allowed him the “chance to know my brother as an adult.” Among his family, he explained, “We didn’t talk about Merle too much.” (Merl’s childhood nickname was “Merle,” pronounced Merlie, but as he grew older, he preferred Merl.) “I was the youngest of six kids—three boys and three girls—I was the baby of the family. I remember my mom crying a lot, but I never really knew why. It was later on, years later, that I understood. But it was hard not knowing the details of Merle’s death. It helped to know what happened.”8 For Eleanor too, Jeff’s arrival provided some modicum of relief. Years later, just before her death, she summoned Jeff to her side and told him what a difference his coming to the door that day meant in her life. And she left him with a final request: “Jeff, you go find the other mothers and tell them—you tell them the truth, that’s what they want to know.”9 However painful the prospect, it was a charge Savelkoul embraced. “I was afraid to share that story again, so two of the members of Team Hawk [another team from the marine corps’ Third Reconnaissance Battalion, Alpha Company] dropped what they were doing, left their jobs, and went with me. We went around [the country] and visited the family members and the headstones, and monuments, of my teammates on Team Striker. Just as Eleanor had requested.”10 By that time, the Allen family had already erected their own stone-and-concrete memorial marker for Merl out at York Island in Lake Superior; both Eleanor and her husband, Alden “Skip” Allen, would be laid to rest beside it, but before their son returned home.

2004 proved a monumental year for Jeff, though in our conversations, first over diner fare and later over the phone, he only mentioned one part of the story. That was the year when Jeff got the promising news of a breakthrough in the military’s efforts to locate the site of the helicopter crash. A joint investigation team had recovered a few articles that appeared to be associated with the loss incident, among them a full deck of fifty-two playing cards—all aces of spades—still wrapped in plastic, and Jeff’s own rosary. The cards, Jeff explained, had an important story behind them, one directly tied to Merl and the brutality, both psychological and physical, of jungle warfare:

Merl was always scheming up something, and constantly writing letters. Recon’s trademark was the ace of spades. It had a significant PSYOP [psychological operations] value. The NVA [North Vietnamese Army] were very superstitious and terrified of them and we left them in “very significant” places in the bush.11 We were handmaking our own cards there in country and getting the company clerk to copy them for us. Merl got this idea and wrote to Bicycle Playing Card Co. He explained our situation and the next thing we know Bicycle sent Merl 52 decks of 52 aces of spades each. Merl was our hero. The rest of us carried a few to the bush, but Merl carried a whole deck.12

Merl Allen.

While the cards evoked Merl’s memory, for Jeff the rosary had an especially powerful, proliferating symbolism. Through its recovery—from the very site and soil of the mountain slope—he felt his connection to the lives left behind: “Along with it came a little bit of dirt and, I feel, the souls of my lost teammates.” Conjoining the places of war (and death) with the places of home (and birth), he took six of the rosary beads, “one for each of the lost, some dirt from each of their markers and some dirt from the Khe Sanh airstrip [part of the marine corps combat base where he first met Merl],” and left them, along with an account of the crash, at the foot of Merl’s memorial on York Island. At last, he wrote, “the team is back home together, at least in spirit.”13

What he didn’t tell me was that in August of that very same year—2004, thirty-seven years after the crash—Jeff Savelkoul was awarded a bronze star for his efforts to save fellow members of Team Striker. The delay in the medal’s conferral resulted from both the catastrophic event and the conditions of the war itself, which was in the middle of one of its most lethal years—at least in terms of American casualties.14 In the military, medal recipients can only be nominated by persons higher in the chain of command, and in this case, they had all died; or so it was believed, until decades later, when it was discovered that an officer had been transferred into the battalion three days before the crash. He was still alive and thus still able to put in for the award. The official citation notes, “Realizing that other members of his patrol and the crew were still trapped inside the helicopter, Lance Corporal Savelkoul tried to assist other members but was not successful.” Even this singled-out merit he deflected back onto Merl and the others who died in the crash. “It’s nice to be recognized, but more importantly, it recognizes the guys who didn’t come home.… This is for them,” he insisted.15

In February 2013, when the Marine Corps Casualty Office contacted Marilyn and her siblings with the news of Merl’s recovery and identification, it was decided among them that Jeff, for years already considered a member of the family, would travel to Hawaii to serve as the special escort, accompanied by an active duty marine corps escort. By that time, the Department of Defense had ceased its program to fund family members’ travel to the island to take custody of remains and escort them home, as Dwayne Spinler had. So the duty—in Jeff’s words, the honor—fell to him. On the phone from Honolulu to a reporter in Wisconsin, he explained how he had dreamed every night for forty-six years of Merl’s return. “Some days it’s not real—but it is now. I just closed his coffin, I’m getting ready to board the aircraft. He’s coming home.”16 Once en route, Jeff shared a letter with the pilots of the flights from Honolulu to Los Angeles and Los Angeles to Minneapolis / St. Paul in which he described Merl’s service and the helicopter crash and explained that he was escorting home the remains of his “teammate, best friend, and hero, from the jungles of Vietnam, 46 years later.” “I thought you’d like to know.”17 During the five-hour layover in Los Angeles, the Delta Air Lines ground crew supervisor “didn’t think an American hero should just sit on the tarmac” and so arranged for a space in an adjacent warehouse where Jeff could wait with Merl. “We drove all the way around LAX. I rode with Merl and couldn’t hold back the tears. As we passed, every truck, every plane (!) stopped. Every ground crew stood at attention, hands on hearts. When we finally got Merl settled, the ground crew all pitched in and bought us a pizza.”18

As Jeff’s descriptions underscore, homecomings such as Lance Corporal Merlin Allen’s are both highly public and intensely private affairs. Out of respect, though I was aware of his identification, I waited until one year had passed before contacting the Allen family about my research and my role in the recovery mission. What follows is an account gleaned from various perspectives—from members of the Allen family and Jeff Savelkoul, veterans at the Duwayne Soulier Memorial VFW post in Red Cliff, attendees of the memorial service, media coverage, and from Amanda Wilmot, the professional photographer whose keen eye captured the homecoming’s route, events, and above all, the people assembled in the work of remembrance that began at the Minneapolis / St. Paul airport on June 28, 2013, and ended on York Island, Lake Superior, the next day, June 29—one day shy of the forty-sixth anniversary of the helicopter crash. Her photographs, which the family shared with me, shed light on this public / private dynamic of LCpl Allen’s homecoming, often providing a visual corrective for scenes I could only imagine based on conversations with those who had gathered to bring Merl home. Though she would explain to me later that “most of the photographs that day were taken blindly because there were constantly tears in my eyes,” she understood the gravity of the task as “documenting a part history,” indeed a history that was “continuing to unfold.”

When the plane touched down at the Minneapolis / St. Paul airport in the early morning of June 28, people were ready. Members of the Allen family, Jeff Savelkoul, and Mariano “Junior” Guy, the one other Team Striker survivor of the CH-46 crash, the funeral director from Bratley Funeral Home in Washburn, Wisconsin, and the six members of the marine corps honor guard detail, in their crisp uniforms and white gloves, were waiting on the tarmac. The Minnesota Patriot Guard Riders had already assembled at their nearby staging site and been debriefed by 5:45 a.m. “Bring your 3 × 5 flag and pole, water, and everything you need to be self-sufficient”—that is, prepared to show their “respect and honor, and finally say ‘Welcome Home’ to this Vietnam War hero.”19 Once the honor guard had lifted the flag-draped coffin from the aircraft cargo container and placed it in the black hearse, Merl’s siblings drew close to touch it, one by one, reunited with their brother (his single tooth) at long last. Shortly thereafter, the convoy departed, met by the Patriot Guard Riders just outside the airport, to begin the two-hundred-mile journey to northern Wisconsin. After crossing the St. Croix River, the Minnesota riders passed the baton of escort to the Wisconsin chapter. They too were at the ready, eighteen bikes in total, joined by Wisconsin State Patrol, county sheriffs, and local police from towns along the way. Formed in 2005 in response to the Westboro Baptist Church and its shameful, bigoted protests staged at military funerals, the Patriot Guard Riders’ mission is two-fold.20 As invited guests of the family, they are to “show our sincere respect for our fallen heroes, their families, and their communities” and “shield the mourning family and their friends from interruptions created by any protester or group of protesters,” doing so through “strictly legal and non-violent means.”21 For especially charged scenes, the thunderous revving of their engines works to drown out the protesters’ hate-filled chants. In this instance, however, the Allens needed no shielding. On the contrary, from the Twin Cities, where well-wishers gathered on overpasses to glimpse the procession of cars and motorcycles, to Washburn, where local residents lined the streets, children included, saluting and waving flags, Merlin Allen was restored to his family and his home state with respectful, solemn fanfare.

His first place of temporary rest was the Bratley Funeral Home in Washburn, where friends and family gathered for a visitation from 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. Patriot Guard Riders in their black leather and jean-jacket vests, armbands, and ball caps stood vigil on the sidewalk outside the building. Their row of three-by-five flags mirrored the sea of red, white, and blue across the street, where scores of handheld flags had been stuck in the boulevard grass and others fluttered in the breeze atop the several dozen flag poles—one for each fallen soldier from Washburn, from WWII onward—in the American Legion memorial flag park across the street. Inside in the funeral home, LCpl Allen’s remains sat on a small table covered in white cloth. The family had traded out the military’s standard wooden urn in favor of a polished box wrought by Casey Allen’s own hands; he picked cherry, a hardwood that Merl had used in most of his own woodworking projects. A display of flowers, artifacts, and photographs surrounded it, including a tripod bearing a framed collection of the medals LCpl Allen had earned in Vietnam, as well as a mounted copy of Executive Order #106 by Wisconsin’s governor Scott Walker. On the occasion of Allen being “laid to rest forty-six years after sacrificing his life on behalf of his nation, far from American soil”—a faint echo of Merl’s own prescient words back in 1967 when he lodged his protest of the proposed national lakeshore park—Walker decreed that “the flag of the United States and the flag of the State of Wisconsin shall be flown at half-staff at all buildings, grounds, and military installations of the State of Wisconsin equipped with such flags beginning at sunrise on Saturday, June 29, 2013, and ending at sunset on that date.”22 While the executive order signaled the official recognition of Merl’s return, the visitation marked the start of a series of localized—both communal and familial—rituals that drew him closer and closer into the intimate sites of his hometown and his youth before war.

The following day, people from Bayfield, Red Cliff, Washburn, and neighboring townships and cities of the North Woods assembled in the gymnasium of the Bayfield High School for a memorial service. Veterans from the region, their branch and membership telegraphed by legion hats, pins, and patches, had arrived to pay their respects. Children and adults filled the folding chairs and packed into the bleachers, many of them wearing yellow ribbons—an emblem of military absence and plea for swift return—pinned to their shirts. To a slideshow projecting images of Merl and scenes from their youth, siblings Cindy, Marilyn, and Casey each recalled their brother, to laughter and tears. So too did “Junior” Guy, who had assumed the role of special escort upon Merl’s arrival in Washburn. Standing before the podium’s microphone, flanked by fellow Team Striker member Jeff Savelkoul, Junior recounted the fateful day and his anguish at losing Merl and the others. He wept openly before the family and the crowd.

“Grief is a state of mind; bereavement a condition,” historian Jay Winter writes. “Both are mediated by mourning.”23 In tracing mourning’s pathway from initial discovery to eventual commemoration undertaken by communities during and after World War I, he notes how “kinship bonds widened”—what we might see as foreshadowing Dwayne Spinler’s “you can find family anywhere” or Jeff Savelkoul’s bond with the Allen siblings and his charge from Merl’s mother. In the case of the Spinler and Allen families, rituals of mourning so delayed seemed to widen these bonds of kinship, however fleeting or enduring, even further. The return of a long-absent fallen service member invited a sense of communion that others were eager to share in; as the flag-festooned streets of Washburn, Bayfield, Red Cliff, and Russell Township announced, the news of homecoming tapped into notions of national belonging and obligation. Dwayne Spinler homes in on this aspect of mourning’s generative effect in his essay: “We met many people who knew my father as a child, in high school, or college. We were grateful for the stories they shared of their time with him. We also met people from the area who had never met him but knew of him. Others had never heard of him until recently. Many came to pay their respects while some just knew they needed to be with us but did not really know why.”24

Members of the Minnesota Patriot Guard Riders await LCpl Allen’s arrival.

Sean Allen reunited with his brother.

Before the memorial service at the Bayfield High School.

On the dock at Little Sand Bay (front row), Mariano “Junior” Guy, Marilyn Neff, Sean Allen, and Jeff Savelkoul.

Carrying Merl home, Mariano “Junior” Guy and Jeff Savelkoul.

The memorial stone on York Island where Merl Allen is buried, alongside his parents, Eleanor and Alden Allen.

Impromptu tributes on York Island.

Cindy Hawkins sprinkling sand on her brother’s final resting place.

To be sure, such a response to identified and returned MIAs is by no means exclusive to the Vietnam War. I once attended a funeral at Arlington National Cemetery for a service member who had been missing in action (unaccounted for) from World War II. Though on a smaller scale than the memorial service held in the Bayfield High School, men, women, and children had gathered at the graveside in Arlington to witness the interment. The three-volley rifle salute, taps, the folded flag handed over to next of kin—there didn’t seem a dry eye among the group of mourners in those moments of ritualized military burial. Only later did I learn that not a single person among the assembled had a firsthand memory of the deceased. None had known him in the sense of ever shaking his hand, sitting around the same kitchen table, or hearing his voice. And yet his marked return had drawn people, total strangers and distant relatives, into the orb of protracted mourning. Here we can see the capacity of missing war dead to foster and stretch bonds of kinship, so much so that acts of mourning the decades-absent fallen come home can leapfrog generations and stir sympathies both phantasmal in origin and immediate in force.

But the unique memory work enabled by the return of MIA remains—“fullest possible accounting” come to fruition—isn’t just about widening bonds of kinship. It’s also about the capacity for those remains, even a single tooth recovered and repatriated, to foster both personalized narratives and localized (rather than strictly national) rituals, and this is where the particular history of the Vietnam War comes into play more explicitly. In his book Remembering War the American Way, historian G. Kurt Piehler argues that the “federal government, by neglecting rituals and memorials, contributed to the alienation of those who fought in this struggle.”25 That alienation extended to the memory of MIAs and their surviving kin as well. Eventually, alienation yielded to the pressures of national memory politics, when demands of “Bring ‘em home or send us back” and “Until the last man comes home” gave way to a sophisticated scientific enterprise of MIA accounting.

If the ensuing ethos of exceptional care sought to rehabilitate the nation’s record in war—among other ways, through the bodies of its unaccounted for—then their return offered local communities a chance to redress that alienation—proof positive of the POW / MIAs slogan, “You are not forgotten.” Four and five decades on, homecoming from a war whose stained history had stained its combatants by association in the immediate postwar years, shifted the focus away from the nation and back onto a single life—a youthful life, a family left behind, and a hometown that could now simultaneously celebrate and mourn his return. Such celebrations, however cut by sorrow, centered on stories. As Jeff Savelkoul explained just before he escorted his best friend home from Hawaii, “The world needs to be told his story. Because then people don’t die in vain and then get forgotten.”26 And so the newspaper coverage of the memorial service for Merlin Allen told his story, and told the story of that storytelling:

Before Allen, whose nickname was Merl, enlisted in the Marines he was a kid with an infectious smile who liked girls, cars and hanging out with his friends. His room was messy. He snuck Mad magazines into the house. He liked to sleep late, somehow managing to listen for the school bus before leaping out of bed, dressing and catching the bus to school, said his younger sister Cindy Hawkins.

Sometimes when he drove his younger siblings to church he talked them out of the money they were supposed to put in the collection plate and instead of going to Mass, he and his brothers and sisters bought chocolate milk and doughnuts, stopping to pick up a church bulletin to take home as “proof”.…

During the funeral, a montage of photos was shown to the crowd—pictures of Allen as a baby, posing for school pictures, swimming, smiling with his siblings, wearing his high school letter sweater, proudly showing off his Marine dress blues uniform. The pictures showed Allen growing older, growing up, then stopping at the age of 20.

People in the crowd sniffled and fought back tears as the final photo showed his name on the Vietnam memorial wall.27

The details of the war itself come in bits and pieces in these articles, with allusions to the helicopter crash, the injuries sustained by Jeff, Junior’s (the other survivor’s) valiant efforts to assist the evacuation.28 But depictions of war as war—the violence Merl and Junior and Jeff were trained to track and unleash, symbolized by that pack of fifty-two aces of spades, hardships Merl faced during his twenty months of service, even his frustration at sacrificing for his country when that country was taking away his family’s land and his home—are strikingly absent. “True war stories,” Viet Thanh Nguyen writes, riffing on Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, “acknowledge war’s true identity, which is that while war is hell, war is normal, too. War is both inhuman and human, as are its participants.”29 And yet, by the logic of Nguyen’s more expansive ethical memory, a public accounting that encompasses the inhuman alongside the human is a lot to ask of families for whom the “time in between” has already inflicted such pain, and who have just been reunited with their missing loved one after so many years of uncertainty.

Moreover, to read depictions of Merl’s “infectious smile” or the portrait of a teenager with a “messy room” and a penchant for chocolate milk and doughnuts as merely a willful erasure of war’s destruction or an intentionally partial memory misses an important facet of these stories. They are an inherently local act of reclamation, a different kind of exceptional care. That is to say, they move beyond the lofty, but often flattening, category of the “fallen hero,” and instead return him, Merl, to the grounding details and relationships of his life before the war, in addition to his service in it. In doing so, stories help return him to his family as the proper guardians of that memory. It was the public telling of such stories, stories invited by the Allens and told by friends, relatives, former classmates, neighbors, local veterans, news media, and even strangers, that helped the Allen family traverse that final leg of their brother’s journey home.

Before he could finally come to rest at home, first there would be a military send-off. Following the memorial service, the long stretch of vehicles, again escorted by the Patriot Guard Riders, wound its way up Highway 13 from Bayfield to Red Cliff. Past the Duwayne Soulier Memorial VFW post on the left, past Buffalo Bay on the right, named after the Chippewa elder who secured the Red Cliff Band territory on the Bayfield Peninsula a century and a half before, and past the Legendary Waters Casino and its marina, they eventually turned onto Old County Highway K and headed north to the campground at Little Sand Bay. Somewhere along Highway K, the column encountered a homespun billboard nailed to a hickory tree: “Now Entering ALLEN Country” it announced in red and blue lettering. Beneath it, on a separate white board, was a blown-up, grainy photograph of Merl in his utility uniform, framed on three sides by the marine corps seal. For those who knew the particular history of the Allen family’s fight to hold on to their property back in the 1960s and 70s, the sign defiantly confronted the dispossessions of land, home, and child / brother, all sacrificed to the nation’s domestic and foreign agendas. If only for this day, Merlin Allen’s homecoming returned that stretch of sandy beach and the island he so cherished to his surviving family, especially his five siblings.

Part of Russell Township, Little Sand Bay is a public campground right on the edge of Lake Superior. I camped there for a few days during one of my visits to Bayfield and Red Cliff. Each morning I would wake up and head to the beach to walk along the narrow strip of dry sand. I’d find a spot, a piece of driftwood, where I’d leave my towel, and then I’d swim out a few yards. I didn’t stay long in the water. Even in the height of summer the Great Lakes can be pretty chilly. I’d return to the main dock to dry off and warm up in the sun, its bright rays by then glinting off the water’s surface. In some small way, I wanted to gain a sense for the place of Merl’s homecoming—not just the flag-lined streets and the tourist-filled shops of Bayfield, but the more enduring spaces of his youth. “I, Merl Allen, will my beach at Sand Bay to the future senior class for their swingers next summer.” The lake and its beaches were one of them; they were also the site of his official military funeral service, where the marine corps honor guard performed its ritual of gifting a folded flag to the fallen’s next of kin. In fact, there would be two flags gifted, twice over, in a display of the widening bonds of kinship that the return of MIA remains had prompted.

The ceremony took place on the dock, where a clutch of black folding chairs had already been set up in neat rows. In front of them stood the same small table draped in white cloth and now flanked by two bright bouquets of red-white-and-blue-themed flowers. Following the honor guard and escort, Jeff and Junior passed between columns of saluting veterans from the region, including the Red Cliff VFW post members, Randy and Butch among them. Junior carried Merl. He placed him on the table, where two folded flags already rested. The family filed onto the dock and took their seats on the chairs, Junior, Marilyn, Sean, and Jeff in the first row, Cindy, Casey, and Sheila, along with spouses and children, behind them. It was a stunningly beautiful summer day, where the vibrant colors of a military funeral—the marine corps dress blues, the honor guard flags, the polished brass, and the gleaming wood of shouldered rifles—were all set off by the lake, sky, and shoreline. The rituals that followed centered on the flags, the material conduit between the military and the family as guardians of the dead. One by one, the honor guard detail unfolded the cloth from its tight triangle and unfurled it above Merl’s urn, holding it aloft for the duration of the three-volley rifle salute. Among the hundreds of photographs that Amanda Wilmot snapped that day, there is one that captures the essence of the unique memory work enabled by Merl’s homecoming: there on the dock, sitting together before the urn, before the single fragment of his recovered remains, the two siblings—the eldest and the youngest, Marilyn and Sean—and the two survivors, Jeff and Junior, hold each other’s hands as they behold this final public tribute to Merl. They are the closest of kin in this instant. Once the honor guard detail had refolded the flags, they presented them one by one to Marilyn. She passed the first to Sean and held on to the next. And then they stood together, turned to Jeff and Junior, and gifted each with a flag.

Dwayne Spinler writes about this very moment in his essay, “Bringing Dad Home.” For him, though the words spoken upon the presentation of the flag were haunting—“On behalf of the President of the United States, the Department of the Air Force, and a grateful nation, we offer this flag for the faithful and dedicated service of your father, Captain Darrell John Spinler”—they represented the first time in the whole process that he felt a “profound sense of peace.” So too, Marilyn described her gradually shifting emotions. When she first learned Merl’s remains had been recovered, she was elated. “But then reality set in. I felt pain, the same pain I felt when Merle was killed. As the days got closer to Merle coming home, the pain lessened. I felt peace in my heart the day we buried Merle on our beloved York Island.”30

IN HIS QUIRKY TREATISE ON SPACE, place, and memory, Species of Spaces, Georges Perec writes, “I would like there to exist places that are stable, unmoving, intangible, untouched and almost untouchable, unchanging, deep-rooted; places that might be points of reference, of departure, of origin: My birthplace, the cradle of my family, the house where I may have been born, the tree I may have seen grow.” But, he tells us, “such places don’t exist,” because just as time wears away at them, our memories also betray us. “Space melts like sand running through one’s fingers. Time bears it away.” For Perec, the writer, there is only one recourse—to write and thus to “leave somewhere a furrow, a trace, a mark or a few signs” of these fragile places.31 But he overlooks other possibilities for keeping sites alive in our memories, as points of not only reference and departure, but also spaces of communion and commemoration. The Allen family crafted their own possibility the day they brought Merl home to York Island.

Once the military rites had been rendered at Little Sand Bay, the family and a select group from among the attendees boarded the Outer Island, a World War II navy vessel (a landing craft, tank) that had helped ferry troops, armor, and supplies to the beaches of Europe in 1944.32 It was an ideal boat for the occasion, both for its historical significance and logistical reasons. It’s about two and a half miles from the Little Sand Bay dock to the southern tip of York Island, where shallow waters and a sandy shoal prohibit other larger vessels from landing. The former amphibious assault craft could drop its ramp directly onto the island beach, allowing its passengers, from little children to more senior attendees, to disembark easily.

As special escort, Junior was entrusted with carrying Merl, the wooden box around which all activity now focused, to the burial site. The group made its way from the boat onto the island, threading through light brush to arrive at a small clearing several yards in from the water’s edge. This place, too, I had visited, two years after the funeral, again to get a sense for where Lance Corporal Merlin Raye Allen finally rested. It is a serene place, bordered by a mix of northland woods—birch, fir, aspen, and pine—and with a carpet of island grass and wild flowers as ground cover. At its center stands the memorial to Merl. In the late summer of 1970, Casey and his father had hauled material over from the mainland, picking a calm day to tow a concrete mixer on their floating swimming dock behind their fourteen-foot Starcraft. Once there, they used beach aggregate to make the concrete and gathered stones from the island. “All the concrete had to be hauled up the steep hill in buckets,” Casey explained, an act of commemoration that would be echoed some forty years later in the bucket chain that moved the soil up to the ridge at the excavation of Merl’s crash site.33 A few weeks later, their uncle Tom, Eleanor’s brother, the son of a stonemason himself, layered the rocks and set the bronze plaque in the center:

IN MEMORY OF

MERLIN RAYE ALLEN

WISCONSIN

L CPL 3 RECON BN 3 MAR DIV

VIETNAM PH

OCT 22 1946 JUN 30 1967

In the intervening years, other markers have been added to the clearing. You can see the more informal “furrows” and “traces”—to borrow from Perec—left behind to punctuate private and collective journeys of commemoration. A tree trunk near the center of the space bears witness specifically to military memory, where various pins and patches are affixed to the bark, the majority of them marine corps emblems. When I visited there, a weathered ace of spades was tacked to the tree. But there are also permanent markers that attest to the intertwined military / family memorial significance of this spot on the island: in 2009, a stone placed by the Alpha Recon Association to honor its brothers “missing and fallen”; in 2007, on the fortieth anniversary of the helicopter crash, a monument to the five members of Team Striker killed, including Dennis Perry, who perished from his wounds two days later, as well as the pilot, Captain John House, with the inscription “Never Returned—Never Forgotten”; and most intimate of all, at the foot of Merl’s memorial, the headstones of his parents, Eleanor Allen, who died in 1999, and Alden Allen, who died in 2001. At that same base, on June 29, 2013, Sean and Casey prepared to bury their older brother beside their parents.

At first, the island wasn’t quite as willing a recipient as planned. The deep, narrow plot had filled with water overnight; though the sky was nearly cloudless that morning, it had rained heavily in the preceding days, leaving the ground saturated. Casey and Sean together had to press their weight onto the urn vault to submerge it. At last the vault settled into place, and the attendees, one by one, took a small handful of sand to sprinkle over the water-filled hole, bathing Merl in the grains of that beach he had so loved. He was finally at rest. From the mountainside in central Vietnam to the examination table in Hawaii to the clearing on York Island, Merlin Raye Allen had traveled a long way to come home from war.

WHEN I ASKED THE ALLEN SIBLINGS—who, importantly, include Jeff Savelkoul—about whether it mattered to them that so little of their brother’s physical remains was recovered and repatriated, they uniformly told me no. As Casey explained, “I was thrilled if one bone chip came home; I knew it was my brother, I finally knew his fate, and he was coming home.”34

Their responses echoed Dwayne Spinler’s. He too understood and accepted why more remains could not be found beyond the three teeth that Marin and the recovery team unearthed from the banks of the Xe Kong River; he trusted the validity of the science that correlated the loss incident with the excavation site and later identified the teeth; and, having escorted him back to Browns Valley, he considered his father home. Dwayne begins his essay, “Bringing Dad Home,” recognizing the good—the exceptional—fortune of that homecoming made possible by a nation bent on returning its fallen to surviving kin: “I am not sure how you are supposed to feel when you find out that the remains of your father, who died in 1967 at age 29 during the Vietnam War, have been found 44 years later. I only know what I felt—shock … confusion … joy … sadness … all of the above. But mostly I was struck with the feeling that my family was extremely fortunate.”35