In the current ‘great conservation debate’, it seems there is increasingly less common ground to stand on. Should we be mourning the ‘End of the Wild’, following Stephen Meyer? Or should we celebrate the ‘New Wild’, as Fred Pearce urges? Are we living through an age of ‘biological annihilation’ or is nature ‘thriving in an age of extinction’?1 Should we follow the call to now fully and responsibly accept human stewardship of an Anthropocene earth? Or is this typical of human hubris and should we be sceptical of any attempt to place humanity at the steering wheel of spaceship earth? Should we be radically mixing societies and biodiversity into new and potentially exciting ‘socionatural’ arrangements or should we radically separate people and much of the rest of biodiversity in order to enable more sustainable futures? Or are all these considerations unrealistic and ought we instead simply to focus on improving mainstream conservation ‘business as usual’? These important questions, and others, are raised by the current debate. We add one more: are there ways to defuse their all-or-nothing, black-and-white connotations and find other ways to frame the Anthropocene conservation debate altogether?

Clearly, the arbiter in this discussion cannot be science. Or, at least, not science alone.2 As we saw in the previous chapter, how to interpret the role of science in conservation and act on its findings is precisely one of the major issues at stake. Science, no matter how much some neoprotectionists and other conservationists would like to believe otherwise, is always already political; its outcomes and their relevance and potential are always subject to broader political, economic, social, cultural, historical, environmental and other contexts. The same goes for nature, as Christian Marazzi explains:

Nature, as Einstein noted, is not the univocal text theorized by the scientists belonging to the Newtonian tradition, who thought that the observation of Nature and the deduction of its internal laws was sufficient to find the scientific legality of the physical world. The experience of theoretical inquiry has actually shown that Nature is, rather, an equivocal text that can be read according to alternative modalities.3

Yet, to say that nature is an ‘equivocal text’ should not be interpreted as a statement of radical postmodern relativism, as Harvey Locke might claim.4 He and other neoprotectionists have a point that several social scientific ‘turns’ into postmodern deconstructionism, new materialism and hybridism have become quite outlandish if not foolish.5 But this does not invalidate the simple fact that different people hold different ideas about reality, science and nature. What is therefore badly needed in the debate, we concluded in the previous chapter, is a logical, coherent and convincing frame or set of principles to help assess the issues at stake, to place them within broader contexts and to enable forms of political action moving forward. The aim of this and the next chapter is to work towards such a frame by delving deeper into the main issues raised in chapter two.

In this way, we want to turn the usual order of things around: instead of presenting a theoretical frame through which to approach the Anthropocene conservation debate, we want to highlight several conceptual, theoretical and logical contradictions within the current debate as the basis for formulating a set of principles through which to assess the debate and move it forward. To do so, it is important to make our starting point and basic assumptions explicit. As previously stated, our analysis is grounded in a ‘political ecology critical of contemporary capitalism’. In the next section, we briefly clarify what we mean by this and how this relates to our conception of theory. From there, we move deeper into the debate, exploring in more detail the two main issues we have identified as both characterizing and dividing different positions within it: the nature–culture dichotomy, in the current chapter; and the relation between conservation and capitalism in the next. Together, these explorations lead up to our evaluation of the debate as the basis for our own alternative proposal of convivial conservation.

A POLITICAL ECOLOGY CRITICAL OF CONTEMPORARY CAPITALISM

Our contention is that a political ecology centred on a critique of contemporary capitalism can shift the Anthropocene conservation debate onto a more stable, coherent, and realistic basis.6 This, to be sure, is not a ‘closed’ theoretical frame where all issues are settled. Just as ‘science’ is political, so is theory, which means that it must always be open.7 This is also not to assert that science or theory must be driven by one’s politics; these should be driven primarily by sound empirical research based on credible methodology.8 But, as these processes are themselves always infused by politics, and occur within larger political contexts, they can only be made sense of by (inherently political) theories of how the world works and can be understood.9 Crucial, therefore, is to make one’s guiding theoretical assumptions explicit, something that is often lacking within the current Anthropocene conservation debate, and perhaps one of the reasons why it is so antagonistic rather than agonistic.10

Our guiding theoretical assumptions are arguably two of the most basic assumptions informing political ecology, namely that ecology is political and that the most foundational and powerful contextual feature to take into account when making sense of ecological issues, including conservation, is (the capitalist) political economy. Yet, the point that these assumptions are broadly shared within the field of political ecology is not the only reason why we believe they provide a good foundation for our discussion. Two further reasons are worth emphasizing, and they also provide a glimpse of how we understand theory and science more generally. First, these two assumptions are not just political: the dominance of contemporary capitalism and the statement ‘ecology = politics’ are also straightforward empirical facts and hence need to be taken seriously in any scientific endeavour focused on conservation.

Second, these assumptions, and their fluid meanings, have been intensely discussed for a long time in political ecology, and there is no agreement on their interpretation. This is crucial, as it means that we can learn from and build on the many theoretical disagreements, contestations and explorations that have animated political ecology over the last decades. Thus, while we state that the assumptions themselves are facts, their interpretation and meaning are not, which is necessary to open up theoretical and political space to move forward and to deal with the assumptions. Specifically, this open and creative approach to theory pursues what McKenzie Wark calls ‘alternative realism’. In her Theory for the Anthropocene, Wark makes the case to move beyond both ‘capitalist realism’ (there is no alternative to capitalism) and ‘capitalist romance’ (the ‘mirror image’ of capitalist realism, which advocates a future similar to a supposedly balanced pre-capitalist past). Instead, alternative realism ‘opens towards plural narratives about how history can work out otherwise’. It is a ‘realism formed by past experience, but not confined to it’. This requires a theorizing that is rooted in material historical experience and in imaginative prospects.11 It must, in short, be revolutionary.12

As we saw, some neoprotectionists make a similar argument when it comes to why they believe their radical proposals should be taken seriously. New conservationists, likewise, are also fully aware of the radical implications of some of their arguments. This awareness on both sides, however, has not hindered their willingness to step into the debate in order to try and effect change in conservation practice. It might have even spurred them on more. This is, we believe, important testimony to the ‘lived realities’ of the debate, and the people behind it. They realize, as do many others, that we live in a time of radical choices and that choices currently being made have far-reaching ramifications. This is why it is crucial to delve deeper into the key issues at stake in the Anthropocene conservation debate.

RADICAL CHOICES AND RAMIFICATIONS

While still in its early stages, the potentially massive ramifications, as well as the foundational nature of the Anthropocene conservation debate, have already been recognized widely. As we intimated in the introduction, these included a range of actors trying to understand the parameters, origins and effects of the debate. This has led to a range of different responses. Some seem rather taken aback by the heated debate, even calling it ‘vitriolic’. Conservation scientists Heather Tallis and Jane Lubchenco, supported by 238 signatories, spearheaded a comment in Nature calling ‘for an end to the infighting’ that, they claim, ‘is stalling progress in protecting the planet’.13 Others welcome the heated debate. Political ecologists Brett Matulis and Jessica Moyer, commenting on this Nature piece, contend that calls for consensus are futile given that there are in fact fundamental incompatibilities between the positions advanced by the two camps in the debate. They also highlight just how narrow a range of participants in the global conservation movement this debate includes and how many other perspectives on appropriate forms of conservation would be excluded even if the two extremes could be somehow unified. They call instead for an ‘agonistic’ conservation politics in which debate is not suppressed but, on the contrary, opened further to include a wider range of perspectives.14

Other commentators have tried to engage more directly with issues in the debate itself. Geographer Paul Robbins, for example, lauded the new conservationist attempts to stop blaming people, especially those who are marginalized, for bad conservation results, which, in his words:

Portends a real shift not just in doing conservation, but in rethinking the basis for all of what would best be termed the ‘Edenic sciences’, including conservation biology as well as the fields of invasion biology and restoration ecology. Channelling their research into the explanation, analysis, and encouragement of diversity where people live and work, the authors herald a fundamental shift in hypotheses and methods in these sciences, as we move forward into the Anthropocene.15

But at the same time as they applaud new conservation for moving beyond old nature–culture dichotomies, Robbins and others worry about the optimism with which Kareiva et al. and many major conservation organizations put their faith in partnering with capitalist corporations. Robbins warns that ‘corporations can be bad news’ and chides Kareiva and colleagues for being naïve in too easily embracing capitalist models of development and corporate funding. Lisa Hayward and Barbara Martinez, similarly, caution that without appropriate risk management and strategies for measuring success ‘“Conservation in the Anthropocene” will diminish conservation’s reputation and its capacity to spur positive change, and, at worst, may justify the distortions of those who seek to profit at the expense of both people and nature’.16

The latter positions resonate strongly with our own. Hence, we will spend some time discussing this issue in more depth later. First, however, we need to do more justice to the nuances in the debate, while also providing more evidence for what we believe are ultimately the two main, interrelated axes of contention: the nature–culture dichotomy and the relationship between conservation and capitalism. We start with the issue at the heart of it all: the nature of ‘nature’ itself.

THE NATURE OF NATURE

First and foremost among the issues of contention within the great conservation debate has always been the meaning of the term ‘nature’. It would, perhaps, not be an exaggeration to say that this is the key foundational issue around which the whole discussion pivots. One of the central components of common critiques of mainstream conservation is that it has, historically, rested on a conceptual distinction between opposing realms of nature and culture that conservation practice has, in a sense, sought to render material through the creation of protected areas from which human inhabitants were often forcibly removed.17 This dichotomy, and the particular understanding of (nonhuman) nature to which it gives rise, has been problematized as a culturally specific construction largely limited to ‘Western societies’ in the modern era. Such a strict separation between opposing conceptual realms, it is argued, does not reflect the different ways in which other peoples throughout the world understand relationships between humans and other living beings.18 So why, precisely, is this dichotomy such a big issue, and how do different actors in the debate deal with it?

To start with the last part of this question, mainstream conservationists have generally been ambivalent about the concept of nature. On the one hand, many claim that a nature–culture separation is an impediment to conservation: it enforces a sense of distance and alienation from nonhumans, and conservationists therefore often call for greater ‘connection with nature’ through direct experience in outdoor landscapes.19 In their rhetoric and actual practice, on the other hand, conservationists commonly continue to reinforce separations between people and the very nature we are all supposed to be part of. This is most visible in the continued enforcement of conventional protected areas, but also in newer market-based mechanisms such as ecotourism, payments for environmental services, and species banking in which conservation and development are supposed to become one and the same.20

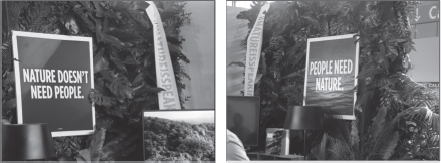

More contradictory still, even as they advocate greater connection with nature, conservationists often simultaneously reinforce a sense of separation from nature. This, then, provides a first glimpse of what is so problematic about the nature–culture dichotomy: humans are supposed to be part of nature, but are at the same time often seen as separate from it. Conservation International’s ‘Nature Is Speaking’ campaign epitomizes this problematic ambivalence (see figure 2). This campaign features a series of short films in which high-profile celebrities like Harrison Ford and Julia Roberts assume the voices of natural forces (such as water and Mother Nature) and decry humans’ rampant assault upon them. One of these short films, narrated by Robert Redford as a redwood tree, insists that the solution to this destruction is for humans to recognize that they are ‘part of nature, rather than just using nature’.21 Yet the campaign’s own motto (‘Nature Doesn’t Need People, People Need Nature’) emphasizes this same separation between people and nature that is seen as the problem, a separation further reinforced by many of these short films in which narrators explicitly speak, as elements of nature, to their distinction from a generic humanity. Julia Roberts, as Mother Earth, for instance, proclaims, ‘I am nature. I am prepared to evolve. Are you?’22

Figure 2. CI signs at the World Parks Congress, Sydney, November 2014.

Photos by Bram Büscher.

Anthropocene conservationists, as we have seen in the previous chapter, embrace the mounting critique of the nature–culture dichotomy. Kareiva and colleagues assert, ‘One need not be a postmodernist to understand that the concept of Nature, as opposed to the physical and chemical workings of natural systems, has always been a human construction, shaped and designed for human ends.’ On this basis they advocate greater integration of human and nonhuman processes within a variety of different strategies, including integrated-conservation-and-development programmes, biosphere reserves, biological corridors, assisted migration routes, and even the creation of ‘novel ecosystems’. Central to all these is a ‘new vision of a planet in which nature – forests, wetlands, diverse species, and other ancient ecosystems – exists amid a wide variety of modern, human landscapes’.23

Since at least the 1990s, neoprotectionists have strongly contested this view. They argue that nature is not a social construction but a real entity that stands to some extent independent, ‘self-willed’ and ‘autonomous’ with respect to human perception and action. From this perspective, those who critically reflect on the concept of nature are themselves often criticized for endorsing an extreme position that denies the existence of physical reality altogether.24 Yet, as with mainstream conservation, this perspective is ambivalent. Some neoprotectionists, like David Johns and Roderick Nash, accept the assertion that humans are part of nature:

How can human behavior be anything but part of Nature? We are the products of evolution; we breathe air, eat, and are otherwise dependent upon the Earth. Unless one invokes the supernatural then, by definition, everything we do is natural, and that doesn’t get us very far.25

Of course humans remain ‘natural.’ But somewhere along the evolutionary way from spears to spaceships, humanity dropped off the biotic team and, as author and naturalist Henry Beston recognized, became a ‘cosmic outlaw.’ The point is that we are no longer thinking and acting like a part of nature. Or, if we are a part, it is a cancerous one, growing so rapidly as to endanger the larger environmental organism.26

At the same time, such statements conflict with a common desire amongst neoprotectionists to preserve nature as a ‘self-willed’ force independent of human intervention and cordoned off within depopulated protected areas. Assertions of the ‘need to share the world with nature’, ‘the will to create a new humanity that respects nature’s freedom and desires’, or that ‘it is wrong for humanity to displace and dominate nature’, again imply a separation between humans and the nature we are supposedly part of.27 This, clearly, is problematic. But another central concern of the global conservation movement illustrates this contradiction – and hence of the role of the dichotomy in the broader Anthropocene conservation debate – even more sharply: the desire not just to protect nature, but to preserve wilderness.

THE REALITIES OF WILDERNESS

For many conservationists, the nature they defend is often directly equated with wilderness.28 Wilderness was paradigmatically defined by the 1964 US National Wilderness Preservation Act as ‘an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.’ As noted in chapter one, the aim to preserve wilderness within protected areas has always only been one model of conservation that has coexisted with other competing approaches from the outset. Yet the North American wilderness park has long stood as the main model for the global expansion of protected areas in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In this way, and further reinforced after the paradigmatic definition by the US Wilderness Act, the very act of preserving wilderness has ensured and even deepened the centrality of the nature–culture binary in global conservation.29

Following Paul Wapner, there are two main reasons why a focus on ‘wilderness’ deepens the dichotomy, one material and one discursive.30 Materially, it is well documented that many areas that are considered wildernesses to be preserved within protected areas were made so by forcibly evicting the former inhabitants of these areas. It is therefore only through violent acts of displacement that they were given the appearance of unpopulated pristineness. What is painfully contradictory here is that the same indigenous people who in many places long managed landscapes that became attractive to conservation were subsequently removed (or even exterminated) in order to preserve what then became ‘wilderness’.31 Rod Neumann astutely labelled this material dynamic ‘imposing wilderness’.32

At the same time, the contradictory material production of wilderness needed also to be discursively produced, in order to be (seen as) legitimate and ‘real’. In Igoe’s perceptive words, this ‘process of erasure had to erase itself’.33 Only by writing people out of landscapes could protected areas also discursively take on the semblance of ‘untrammeled’ wilderness. Needless to say, these contradictory dynamics, which were also often racist, colonialist and imperialist, have been heavily criticized. The foundational text here is William Cronon’s essay ‘The Trouble with Wilderness’, where he stated that wilderness ‘far from being the one place on earth that stands apart from humanity, is quite profoundly a human creation’.34 Cronon and others challenged the very idea that wilderness can or ever has existed, which de facto renders it ‘an impossible geography’.35

This critique of the ontology of the wilderness conventionally prized by conservation is one of the main issues that new conservationists have embraced in support of their position. As Kareiva et al. assert,

The wilderness ideal presupposes that there are parts of the world untouched by humankind … The truth is humans have been impacting their natural environment for centuries. The wilderness so beloved by conservationists – places ‘untrammeled by man’ - never existed, at least not in the last thousand years, and arguably even longer.

On this basis they contend that:

Conservation cannot promise a return to pristine, prehuman landscapes. Humankind has already profoundly transformed the planet and will continue to do so … conservationists will have to jettison their idealized notions of nature, parks, and wilderness – ideas that have never been supported by good conservation science – and forge a more optimistic, human-friendly vision.36

Marris, similarly, describes a ‘post-wild’ world in which we ‘must temper our romantic notion of untrammeled wilderness and find room next to it for the more nuanced notion of a global, half-wild rambunctious garden’. This, she suggests, is

a much more optimistic and a much more fruitful way of looking at things … If you only care about pristine wilderness … you’re fighting a defensive action that you can never ultimately win, and every year there’s less of it than there was the year before … But if you’re focused on the other values of nature and goals of nature, then you can go around creating more nature, and our kids can have a world with more nature on it than there is now.37

This, clearly, is one of the contentions most disputed by neoprotectionists. Wilson insists that ‘areas of wilderness … are real entities’.38 In a section entitled ‘wilderness is real’, Locke even argues that ‘to those of us who have experienced such primeval places, claims of the non-existence of wilderness are absurd and offensive’.39

A number of interrelated arguments are mobilized to support these assertions. First, neoprotectionists dispute research concluding that indigenous inhabitants have long tended many ‘wilderness’ areas. Instead, they contend that in reality there were far fewer such inhabitants than researchers claim and that these inhabitants altered the landscape far less than is suggested. Foreman points out that ‘the combined population of Canada and the United States today is over 330 million’ while ‘the pre-Columbian population was little more than 1 percent of that’. Moreover, ‘There were large regions rarely visited by humans – much less hosting permanent settlements – because of the inhospitality of the environment, the small total population of people at the time, uneven distribution, limited technology, lack of horses, and constant warfare and raiding’ and hence human ‘impact until very recently was scattered and light’. As a result, environmental campaigner and Earth First! co-founder Dave Foreman asserts, ‘The issue is not whether natives touched the land, but to what degree and where. Even if certain settled and cropped places were not self-willed land due to native burning, agriculture, and other uses, it does not follow that this was the case everywhere’.40 He favourably quotes geographer Thomas Vale who argues that:

The general point … is that the pre-European landscape of the United States was not monolithically humanized … Rather, it was a patchwork, at varying scales, of pristine and humanized conditions. A natural American wilderness – an environment fundamentally molded by nature – did exist.41

Second, neoprotectionists contest claims concerning the number of people displaced to create wilderness protected areas and the extent to which this occurred. Environmental historian Emily Wakild asserts that ‘history in many cases shows that people were not kicked out; national parks were designed with them in mind’.42 Environmental sociologist Eileen Crist adds that ‘recent research has revealed that systematic data about the impact protected areas have had on local communities worldwide (and under what conditions that impact has been beneficial or detrimental) is “seriously lacking.” What’s more, the overwhelming majority of the world’s rural and urban poor do not live near wilderness areas’.43

Third, in a different yet related vein, neoprotectionists hold that an area need not be entirely ‘pristine’ to be considered wilderness. Wilson points out that ‘Nowhere in the U.S. Wilderness Act do words like “pristine” appear’. Foreman agrees: ‘Places do not have to be pristine to be designated as wilderness; the Wilderness Act never required pristine conditions’. Wuerthner goes further than this insisting that ‘no serious supporters of parks believe these places are “pristine” in the sense of being totally untouched or unaffected by humans’. And in responding directly to Kareiva et al., Kierán Suckling, the Executive Director of the Center for Biological Diversity retorts:

Do Kareiva et al. expect readers to believe that conservation groups are unaware that American Indians and native Alaskans lived in huge swaths of what are now designated wilderness areas? Or that they mysteriously failed to see the cows, sheep, bridges, fences, fire towers, fire suppression and/or mining claims within the majority of the proposed wilderness areas they have so painstakingly walked, mapped, camped in, photographed, and advocated for? It is not environmentalists who are naïve about wilderness; it is Kareiva et al. who are naïve about environmentalists. Environmental groups have little interest in the ‘wilderness ideal’ because it has no legal, political or biological relevance when it comes to creating or managing wilderness areas. They simply want to bring the greatest protections possible to the lands which have been the least degraded.44

Some even contend that places inhabited by low numbers of indigenous peoples can in fact still be considered wilderness. Wilson insists that ‘wildernesses have often contained sparse populations of people, especially those indigenous for centuries or millennia, without losing their essential character’.45 Environmentalists Harvey Locke and Philip Dearden assert that ‘low intensity indigenous occupation of an area through low impact subsistence activity is consistent with the wilderness concept’. The author and environmentalist Paul Kingsnorth elaborates:

The Amazon is not important because it is untouched; it’s important because it is wild, in the sense that it is self-willed. Humans live in and from it, but it is not created or controlled by them. It teems with a great, shifting, complex diversity of both human and nonhuman life, and no species dominates the mix.46

Neoprotectionists, in short, have tried hard to re-operationalize and reconceptualize the concept of wilderness in order to respond to, and even accommodate, some of its material and discursive histories. In this they keep coming back to one main point, captured poignantly by Wolke: ‘Absolute pristine nature may be history, but there remains plenty of wildness on this beleaguered planet.’47 This perspective allows for the reintroduction of the wilderness as a relative rather than absolute concept. Thus, Locke and Dearden,

acknowledge that there are few areas on Earth that at some time have not sustained human impacts. We know that every drop of rain that falls anywhere on this planet bears the imprint of industrial society. But we also know that there are great variations in the degree of humanity’s impacts on the rest of nature. The difference in human impact on nature from the practice of intensive cultivation in a humanized landscape compared to the impacts of deposition of minute traces of industrial chemicals in a wild, uncultivated and unpopulated area is not just a difference in degree, it is a difference in kind. The term wilderness captures this difference.48

Bringing these different lineages in the concept’s development together, we again see the same problematic and ambiguous binary: wilderness should be able to contain and has always contained people, but, at the same time, should ideally not contain people. What, arguably, makes this discussion sharper than, or simply different from, the ‘nature’ discussion above is that it is harder to erase or deny the dichotomy. At the very least, it shows important nuances in the debate to which we could not yet do justice in chapter one, namely that we have seen that neoprotectionists are not as rigid on this point as it might sometimes appear. In fact, we need to go one step further still.

FROM WILDERNESS TO WILDNESS, VIA ‘REWILDING’?

In response to these debates concerning the nature of nature and realities of wilderness, many advocate a conceptual shift from ‘wilderness’ to ‘wildness’.49 Legal anthropologist Irus Braverman even sees this shift as one of the central dynamics of contemporary conservation more generally. The shift from wilderness to wildness, has, in fact, been endorsed by neoprotectionists, Anthropocenists and critical social scientists alike, albeit in quite different forms. Briefly outlining these will help to further clarify the importance of and nuances in the role of the nature–culture dichotomy within the debate.

Already before they suffered a full-frontal attack for their dismissal of the concept of wilderness, new conservationists had started emphasizing how their proposal retains elements of ‘wildness’ within a human-dominated landscape. Marris, for instance, envisions ‘a global, half-wild rambunctious garden’, while Kareiva et al. advocate a ‘tangle of species and wildness amidst lands used for food production, mineral extraction, and urban life’.50 This, obviously, comes quite close to how critical social scientists have advanced their own vision of ‘feral’ landscapes incorporating elements of ‘wildness’.51 As Cronon stated some time ago, ‘If wildness can stop being (just) out there and start being (also) in here, if it can start being as humane as it is natural, then perhaps we can get on with the unending task of struggling to live rightly in the world – not just in the garden, not just in the wilderness, but in the home that encompasses them both.’52 Jamie Lorimer more recently elaborated:

There is a common assumption that the end of Nature equates to an end to wildness, a domestication of the planet. This is the case only if we accept the mapping of wildlife to wilderness, to places defined by human absence. Instead, wildlife lives among us. It includes the intimate microbial constituents that make up our gut flora and the feral plants and animals that inhabit urban ecologies. Risky, endearing, charismatic, and unknown, wildlife persists in our post-Natural world.53

Yet some in the neoprotectionist camp insist that this is a slippery slope in that all wildness should not be considered equal. Seeking to recapture a notion of wilderness in the face of such slippage, Michael Derby and colleagues contend ‘that the “wilderness” we encounter in cities is qualitatively different from what is encountered in predominantly undomesticated areas. Despite the procession of birds that might flock overhead, the coyotes that roam urban alleyways, or the families of raccoons that rummage through garbage bins, cities are not wilderness on its own terms.’ As a result, these authors assert:

The wilderness that we know of the backcountry is predominantly wild beyond our wanting and doing, it is self-arising and unpredictable; we have not tamed it or turned it into a delightful display of aesthetics. It is messy and complex beyond our control and beyond easy understanding. It forces us to be humble and attentive in ways that seem more rare within an urban setting. As educators, we need to acknowledge such radical differences in the knowing and being that take place across locales, from the urban park to the arctic tundra and everything in-between.54

Wildness, for both neoprotectionists and new conservationists, is thus understood as a spectrum, with fully human-dominated landscapes on the one end and (almost) fully nature-dominated landscapes on the other. A key objective is to ‘rewild’ areas to a state of wildness approximating to an acceptable degree a pre-human – or at least pre-modern – landscape. For new conservationists, this is merely one strategy among many intended to create a variety of landscapes combining humans and nonhumans in myriad combinations.55 For neoprotectionists, however, rewilding towards a pre-human baseline becomes the core strategy of the new back-to-the-barriers programme. The very concept, indeed, was developed by neoprotectionists. As Lorimer and colleagues describe, ‘The term rewilding first emerged from a collaboration between the conservation biologist Michael Soulé and the environmental activist David Foreman in the late 1980s that led to the creation of The Wildlands Project.’56 The idea was expanded by Dave Foreman as a novel paradigm for conservation throughout North America, via his Rewilding Institute, a project he, Soulé and others subsequently promoted in the flagship scientific journal Nature.57 A similar proposal to rewild Europe has been advanced, coordinated by the group Wild Europe.58 Rewilding plans have been discussed and/or developed for various other areas as well.

Although many variations of the concept exist, the basic idea of rewilding is to cordon off spaces that have been previously subject to human alteration so that ‘natural’ processes can take over and evolve of their own accord.59 Rewilded spaces can range from small isolated plots like the well-known Oostvaardersplassen in the Netherlands, to the ambitious vision of rewilding whole continents, like North America, by creating vast ranges inhabited by introduced species bearing resemblance to animals that were endemic to the continent before humans’ arrival. As this proposal makes clear, a common but not universal ground for different rewilding projects is ‘a desire to shift the reference baseline for conservation towards the ecological conditions that existed at the end of the Pleistocene’.60

As George Monbiot describes, as opposed to conventional conservation, which ‘seeks to manage nature as if tending a garden’, rewilding aims ‘to permit ecological processes to resume’. It is about ‘resisting the urge to control nature, and allowing it to find its own way’. Monbiot claims, ‘the ecosystems that result are best described not as wilderness but as self-willed: governed not by human management but by their own processes’.61 Rewilded spaces, however, do not solve the contradiction of the human–culture dichotomy; they are ‘man-made to be wild, created from nothing to look as if [they] had never changed’. To achieve this, they must therefore be intensely managed to appear as if unmanaged, left to their own devices. In the process, consequently, the rewilding ‘concept tends to reinforce the line between humans and nature’.62

What is ironic – and very interesting in relation to this book’s discussion – is that rewilding is a strategy promoted by both the new conservationists and some of their neoprotectionist critics as ‘a model for conservation in the Anthropocene’.63 Marris includes rewilding as a central element of her rambunctious garden, while Soulé was among the group to first propose the plan to rewild North America (even if he and compatriots, as we have seen, dispute the Anthropocene idea per se). A common rewilding strategy, then, is approached from two opposite viewpoints: a recuperation of a semblance of wilderness, on the one hand; a ‘post-wild’ plan to consciously make and manage nature, on the other. In this and other ways, the distance between new conservation and neoprotectionist positions seems to diminish substantially. But they remain far from convergent, and neither camp resolves or deals satisfactorily with the nature–culture dichotomy.

DISSECTING THE DICHOTOMY

So where do we stand on the question of the nature–culture dichotomy? What is clear from the preceding discussion is that new conservationists have put their finger on this sore spot in the history, theory and practice of conservation in a way that many critical social scientists using similar or related arguments have rarely been able to do. Anthropocenists have even been able to push many hardcore neoprotectionists to not only think about the issue in a profound way but also to acknowledge, to varying degrees, its importance and to respond to the challenges posed. Yet, how new conservationists have further developed this point deserves closer scrutiny and will lead us necessarily to the other main issue in the debate: the relationship between conservation and capitalism.

Central for new conservationists is the fact that conservation is not any longer something that is done behind symbolic and material fences or through the separation of ‘humans’ from ‘nature’. Instead, they stress that conservation must be done throughout all human activity, and especially economic activity. That is, the conservation of nature should become valued throughout the economy in such a way that contradictory dichotomies between humans and nature are no longer necessary to ‘protect’ nature ‘from’ people. For this to occur, the material economy must be reconfigured so as to create value for ecology and economy alike. It is in this way that they connect a critique of the nature–culture dichotomy to the promotion of capitalist conservation.

This position, however, is logically and historically untenable. We argue that the strides made towards moving beyond the dichotomies new conservationists decry are deeply hindered by their endorsement of capitalist conservation. There are several important reasons for this. First and most fundamentally, it is under capitalism itself that this stark distinction between human and nonhuman natures has been reinvented and reinforced.64 The key dynamic through which this happened is what Marx called the ‘metabolic rift’. This concept describes ‘the process whereby the agronomic methods of agro-industrialisation abandon agriculture’s natural biological base, reducing the possibility of recycling nutrients in and through the soil and water’.65 Simultaneously, it signals how social life in urban areas has been progressively separated from the productive capacity of rural spaces during the development of capitalism from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries onwards.66 All this meant not only that capitalist agriculture had to sustain productivity on a ‘deteriorating ecological base’67 but that the development of capitalism increasingly succeeded in fundamentally changing how many humans relate to and think about (the rest of) nature.68

This latter point is worth dwelling on a bit more, as it goes to the roots of why so many philosophers as well as social and natural scientists have argued, and continue to argue, that the nature–culture dichotomy is deeply problematic. World systems sociologist Jason Moore even argues that this ‘dualism drips with blood and dirt, from its sixteenth century origins to capitalism in its twilight’.69 The reason for making such a strong statement is that the specific nature–culture dichotomy inaugurated by the onset and development of capitalism allowed for new forms of rational, technocratic, mechanistic and profit-driven manipulation of nature – including humans and, especially, women. This manipulation could only be morally, ethically or socially permissible – even thinkable – if humans saw themselves as different – or rather, became alienated – from ‘the rest of nature’.70 Carolyn Merchant’s exposition of what she calls ‘the death of nature’ is still seen as the classic statement of what this perspective leads to. Through this term, she wanted to draw attention to the reduction of nature to an inanimate, technocratically manipulable object:

The removal of animistic, organic assumptions about the cosmos constituted the death of nature – the most far-reaching effect of the scientific revolution. Because nature was now viewed as a system of dead, inert particles moved by external, rather than inherent forces, the mechanical framework itself could legitimate the manipulation of nature. Moreover, as a conceptual framework, the mechanical order had associated with it a framework of values based on power, fully compatible with the directions taken by commercial capitalism.71

This portrayal of nature would be totally unacceptable to most neoprotectionists, who are generally keen to emphasize the deep spiritual, ethical or otherwise ‘inherent’ values and ‘forces’ of a ‘self-willed’ nature.72 Indeed, this is precisely why wilderness is so important to them, namely as a counter to the mechanical, rational, technocratic (and often literal) ‘death of nature’ in so many places ‘developed’ by a globalizing capitalist economy.73 The history of conservation, more generally, is analogous to this argument, in that it served as a counter to the rapid destruction (and subjugation) of nonhuman nature brought about by emergent forms of uneven capitalist development. The irony here – and this brings us to a second fundamental point – is that the very effects of the nature–culture dichotomy leading to the death of nature were increasingly countered by a deepening of this same dichotomy, in materially and discursively separating people from nature, through conservation generally and, especially, through the development of protected areas.

CONSERVATION, CAPITALISM AND THE NATURE-CULTURE DICHOTOMY

In other words – and this is a crucial argument in the book – conservation and capitalism have intrinsically co-produced each other, and hence the nature–culture dichotomy is foundational to both. This point can, again, quite easily be illustrated by looking at historical evidence, in particular the earliest foundations of modern conservation that were laid in a swiftly industrializing Great Britain in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. As has been highlighted many times by different authors, it was during this time that the infamous enclosure movement not only established elite tracts of ‘wild’ lands mostly used for preservation and hunting but at the same time forced people out of rural subsistence and so aided in the formation of the labour reserves that industrial capitalism needed.74

Political Economist Michael Perelman, in particular, shows how the English Game Laws that prohibited rural dwellers and peasants from hunting and collecting wood from 1671 onwards ‘became part of the larger movement to cut off large masses of the rural people from their traditional means of production’. This combined dynamic of rural dispossession and emerging elite appreciation for ‘wild’ lands increasingly led, later in the eighteenth century, to what Perelman refers to as a ‘new vision of nature’. According to him, ‘polite society no longer admired highly artificial landscapes. Nature was to be managed in such a way that it would look natural.’75 In other words, early bourgeois ideas about conservation were directly linked to processes of capitalist accumulation and the separation of people from land and ‘biodiversity’.76 This separation, as Environmental historian Dorceta Taylor shows, was further reinforced through the development of country estates, green ‘urban enclaves’ and urban parks in England and, later, the north-eastern US, allowing elite industrialists to distinguish themselves, and help spur ‘early conservation efforts’.77

These dynamics intensified unevenly along with capitalism itself and spread, through subjugation and colonization, among other processes, to different parts of the world. According to Igoe, the spread of this dichotomous, western form of (what was to become ‘mainstream’) conservation moved principally from England to the United States and through colonization to other parts of the world but had several other forms and origins as well, including from France, Germany and elsewhere.78 This process of the intensification and concomitant spread of conservation and capitalism, clearly, is enormously complex and multidimensional, and cannot here be treated in the depth it deserves.79 Yet the historical fact remains that conservation, and in particular the creation of nature reserves and fortress protected areas, played a crucial role in what Marx called ‘primitive accumulation’: the original capitalist process of wresting people from the land through acts of often violent enclosure, forcing them to move across the metabolic rift from country to town in search of urban wage employment.

In her insightful article connecting conservation and primitive accumulation, political ecologist Alice Kelly argues that ‘protected area creation, like primitive accumulation, is a violent, ongoing process that alters social relations and practices which can be defined by the enclosure of land or other property, the dispossession of the holders of this property and the creation of the conditions for capitalist production that allow a select few to accumulate wealth’.80 Importantly, she shows that the people displaced by protected area creation are not necessarily moved in order to create a workforce for capital; they often become simply ‘surplus populations’.81 Instead, capital accumulation through protected area creation can also be ‘direct’ through the commodification of nature wrought by (eco) tourism and other market mechanisms.82

These forms of conservation commodification, in turn, come with their own ways of reinforcing the nature–culture dichotomy: in trying to connect people to nature, ironically, they often have the opposite effect of further separating them.83 Mechanisms like payment for environmental services, biodiversity offsets, and wetlands banking, for instance, all entail efforts to deliver revenue to resource-dependent populations to support conservation as an offset for the impacts of intensified development elsewhere.84 As Melissa Leach and Ian Scoones point out in relation to carbon offset schemes, ‘almost by default, and often against the wishes of project designers, “fortress” forms of conservation forestry in reserves, or uniform plantations, under clear state or private control, become the only way that carbon value can be appropriated through these mechanisms’.85

Moreover, the transfer of funds in these mechanisms is almost always from North to South, grounded in the rationale that offsets are most efficient when directed to where opportunity costs are lowest.86 In the process, these neoliberal conservation mechanisms reinforce a separation between those living in industrialized societies and the ‘natural’ spaces these people are invited to visit or conserve elsewhere. Ecotourism, probably the most common form of support for community-based conservation, is then promoted as a means to overcome this division by transporting participants ‘back to nature’ where their payments can incentivize local conservation efforts.87 As a result of such practices, the nature–society division is effectively globalized as a component of uneven development.

CONCLUSION

Much more could be said about these historical dynamics and indeed the importance of extensive historical analysis for understanding contemporary conservation more generally. But the key point that this chapter aimed to make is that the nature–culture dichotomy has long been and continues to be deeply implicated in the continuing co-production of capitalism and conservation. This often occurs, as we have shown, even under approaches that self-consciously seek to collapse the dichotomy by integrating economic and ecological aims in particular spaces. Hence, even if newer market-based conservation mechanisms, such as payments for ecosystems services or natural capital accounting, intentionally seek to overcome the separation between nature and people imposed by the fortress conservation model, they commonly risk reinforcing this same divide through the boundary-making promotion of capitalist logics.88 Consequently, even when actors deliberately try to move away from the nature–culture dichotomy, as the new conservationists do, they still risk reproducing it in practice if they rely on capitalist mechanisms to achieve conservation.89

Phrased differently, while new conservation aims to do away with certain nature–culture dichotomies, particularly that between the ‘wild’ and the ‘domesticated’, they do not discuss or even acknowledge other, subtler yet fundamental dichotomies that they establish or strengthen through their support for capitalist conservation. While new conservation’s commitment to moving beyond the nature–culture dichotomy goes deeper than mainstream conservation, it is still not very deep.90 After all, mainstream conservation, while adhering mostly to ‘established’ western boundaries around nature for conservation, also commonly acknowledges that this alone is not enough and that a more all-encompassing ‘sustainable’ or ‘green’ socio-ecological system needs to be built as well.

In essence, then, new conservation may seem to be a radical alternative to mainstream conservation, but in practice it is decidedly less so. The focus of the new conservation on (overcoming) dichotomies differs from mainstream conservation in degree, not in kind. Both mainstream and new conservation commonly place their faith in capitalist conservation to save nature, which, as we have shown in this section, paradoxically reinforces the very dichotomy that new conservation wants to overcome. This, however, is only one aspect of the troubles with capitalism and its relation to conservation.