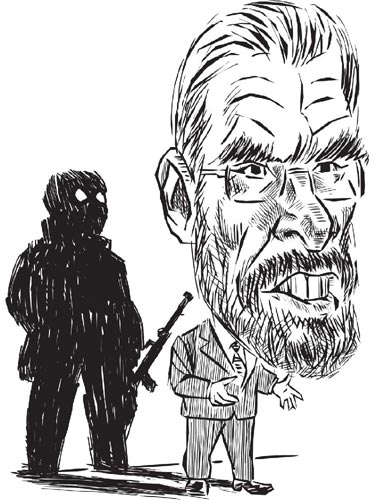

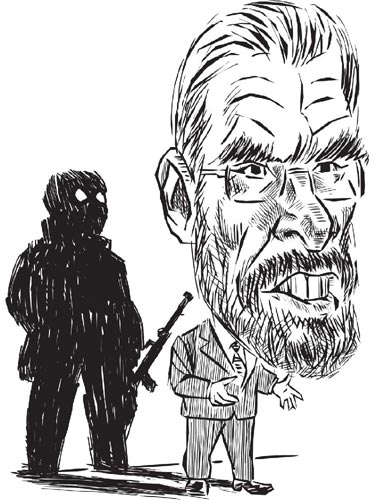

25 Gerry Adams

Everyone knows Gerry Adams was not just ‘in’ the IRA but in it at a pretty senior level. Innumerable times it has been written that for many years he was Commander of the Belfast Brigade of the Provisional IRA. He denies it, but has not sued anyone for what, if it is untrue, must surely strike him as a grave slur on his character. Books have been written linking him to some of the ugliest operations of the IRA – for example, the ‘disappearance’ of Jean McConville in 1972. Jean McConville was a young widow who came to the aid of a young British soldier dying in the street. For this she was abducted by the IRA, taken to a secluded place, shot once in the head and buried on the spot. It would be many years before her body was found, accidentally, by a man who came across a scrap of clothing while out playing with his child.

Gerry Adams told Jean McConville’s family that he had nothing to do with these events, that he was in prison at the time. This was untrue. Everyone knew that he was the senior commander in Belfast when this murder was carried out.

The great fiction of the ‘republican movement’ has been the idea of a separation between its political wing, Sinn Féin, and the ‘freedom fighters’ in the IRA. Everyone knows this was a necessary fiction to avoid imprisonment. When the conflict was brought to an end by the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, many republicans came forward to admit to their former freedom-fighting activities. Martin McGuinness, for example, admitted that he had been a senior figure in the IRA and took responsibility for the pain and grief he had inflicted on so many. He refused to go into details but still it was felt that he had gone some way towards atoning for any wrongs he had committed.

But not Gerry. Clinging to the fiction, Adams insisted that he had never been in the IRA. In fact, he told Gay Byrne on The Late Late Show that he had never so much as thrown a stone during a riot. He was a politician, not a freedom fighter. Mind you, he did not condemn freedom fighting – there had, after all, been a war on. It’s just that he hadn’t been a fighter himself.

In the immediate wake of the Good Friday settlement, this didn’t seem to matter. Adams had been a key figure in the delicate process by which peace was achieved. Indeed, as a senior republican who was prepared to risk his own safety by talking the republican movement around, he might well be deemed the most critical figure in that process. For a short time he was something of a hero. Commentators who had previously attacked Gerry Adams and all his works and pomp now acknowledged his statesmanlike qualities. Very few people in the Republic any longer believed that there had been any ‘war’, but were glad that, however it was to be described, it was now over. The voters of the Republic had even agreed to dismantle their own constitutional aspiration to the eventual unity of their country by agreeing to amend Articles 2 and 3 of the Irish Constitution, Bunreacht na hÉireann, just to stop the Provos slaughtering people. More and more nationalists in the Republic were coming around to the view that the whole thing had been an unnecessary exercise in egotism and viciousness by a generation of Northern thugs who sought to appropriate the national flag and the history it signified so as to legitimize what was really no more than a squalid turf war pursued by ruthless criminals. After years of extending tacit support to the ‘armed struggle’, many people had become persuaded that, although the Brits and the unionists had much to answer for, the IRA’s response had been utterly disproportionate and deeply immoral. After thirty years of conflict and more than 3,000 deaths, the Provos had achieved nothing more than had been on the table at the beginning. Now they were prepared to exchange all the alleged principles on which they had fought their ‘war’ for a few seats in an assembly that could have been agreed nearly three decades previously if they had been prepared to be reasonable. They had fought for ‘freedom’ and settled for power.

Nevertheless, in the early days of the new-found peace, people were prepared to indulge Gerry Adams in his fictive endeavours. People understood that it was sometimes necessary to be less than totally truthful in the interests of peace and harmony. Because everyone had been so anxious to ensure that the peace was maintained, it was considered that a certain latitude should be accorded to Gerry’s pretences. If he had just kept his mouth shut, people might have been able to live with it.

But in his every public utterance as a politician, Gerry adopted a high moral tone about corruption, criminality and wrongdoing. He seemed not to understand the contradictions of his banging on about the alleged criminality of others when he refused to admit to his own past. He berated bankers, freeloading politicians and paedophile priests, demanding that heads be delivered on plates and keys be cast off the edges of cliffs. He did not blink once at the irony of it all. Adopting the ideological palette of a left-liberal politician, he pontificated about equality and women’s rights. He seemed to have forgotten all about Jean McConville and her truncated life as a woman and mother. He attacked the continuing campaigns of irredentist republicans as though he had never fired a shot in anger in his life. Even when he was implicated in a controversy in which his own brother was accused of abusing his daughter, who came out to say that she had told Gerry all about it many years before, Gerry did not break his stride in demanding the resignations of bishops who had failed to blow the whistle on pervert priests.

All this has had a gruesome effect on the stomach of modern Ireland. People could not help finding it strange that a man who had, to their certain knowledge, been up to his oxters in the blood of innocents, should now presume to be regarded as the conscience of the Irish nation. It made people want to throw up. It sent their moral compasses crazy. But still they had to listen to it, because Gerry was now a fully constitutional politician whose past was nobody’s business but his own.