Introduction

THE NAME ANZA-BORREGO combines an important historical figure and the desert wilderness that still exists today. Anza refers to Juan Bautista de Anza, whose expeditions opened the first roadway into California. Borrego is the Spanish word for “lamb”—fitting because the region is home to wild Peninsular bighorn sheep. In essence, the life and journeys of de Anza provide a metaphor for the idea of progress and the settling of lands. The Peninsular bighorn sheep, now endangered, represent the wild. Thus, the joining of these two words demonstrates the delicate balance between civilization and wilderness, which is well presented in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. While the park is open to visitors, some areas are subject to a few months’ annual closure to protect the sheep’s water sources, so the struggle continues to preserve the land while allowing human enjoyment. Continued reevaluation sometimes results in change. As recently as 2005, a large portion of park acreage was permanently closed to vehicle traffic to protect natural habitat. Foot travel is still allowed and, with respect and care by visitors, will continue.

As hikers, we appreciate our parklands as a valuable resource, and we strive to honor the delicate balance between ourselves and nature.

How to Use This Guidebook

THE OVERVIEW MAP AND OVERVIEW-MAP KEY

Use the overview map to assess the location of each hike’s primary trailhead. Each hike’s number appears on the overview map, on the map key facing the overview map, and in the table of contents.

TRAIL MAPS

Each hike contains a detailed map that shows the trailhead, the route, significant features, facilities, and topographic landmarks such as creeks, overlooks, and peaks. The author gathered map data by carrying a Garmin Etrex GPS unit while hiking. This data was downloaded into DeLorme’s TopoUSA digital mapping program and then processed by expert cartographers to produce the highly accurate maps found in this book.

ELEVATION PROFILES

Corresponding directly to the trail map, each hike contains a detailed elevation profile. The elevation profile provides a quick look at the trail from the side, enabling you to visualize how the trail rises and falls. Note the number of feet between each tick mark on the vertical axis (the height scale). To avoid making flat hikes look steep and steep hikes appear flat, appropriate height scales are used throughout the book to provide an accurate image of the hike’s climbing difficulty. Elevation profiles for loop hikes show total distance; those for out-and-back hikes show only one-way distance.

GPS TRAILHEAD COORDINATES

To collect accurate map data, the author hiked each trail with a handheld Garmin Etrex GPS unit. Data collected was then downloaded and plotted onto a digital U.S. Geological Survey–based topographic map. In addition to rendering a highly specific trail outline, this book also includes the GPS coordinates for each trailhead in two formats: latitude–longitude and UTM (Universal Transverse Mercator). Latitude–longitude coordinates employ a grid system that indicates your location by crossroading a line that runs north to south with a line that runs east to west. Lines of latitude are parallel and run east to west. The 0º line of latitude is the equator. Lines of longitude are not parallel, run north to south, and converge at the North and South poles. The 0º line of longitude passes through Greenwich, England.

Topographic maps show latitude and longitude as well as UTM grid lines. Known as UTM coordinates, the numbers index a specific point, also using a grid method. The survey information, or datum, used to arrive at the coordinates in this book is WGS84 (versus NAD27 or WGS83). For readers who own a GPS unit, whether handheld or onboard a vehicle, the latitude–longitude or UTM coordinates provided on the first page of each hike may be entered into the GPS unit. Just make sure your GPS unit is set to navigate using WGS84 datum. Now you can navigate directly to the trailhead.

Trailheads in parking areas can be reached by car, but some hikes still require a short walk to reach the trailhead from the parking area. In those cases, a handheld unit is necessary to continue the GPS navigation process. That said, readers can easily access all trailheads in this book by using the directions given, the overview map, and the trail map, which shows at least one significant road leading into the area. But for those who enjoy using the latest GPS technology to navigate, the necessary data has been provided. A brief explanation of the UTM coordinates for Rainbow Canyon Loop follows.

The UTM zone number 11 refers to one of the 60 vertical zones of the UTM projection, each of which is 6 degrees wide. S refers to horizontal zones, each of which is 8 degrees wide except for Zone X (12 degrees wide). The easting number 550780 indicates in meters how far east or west a point is from the central meridian of the zone. Increasing easting coordinates on a topographic map or on your GPS screen indicate that you are moving east; decreasing easting coordinates indicate that you are moving west. The northing number 3652244 references in meters how far you are from the equator. Increasing northing coordinates indicate you are traveling north; decreasing northing coordinates indicate you are traveling south. To learn more about how to enhance your outdoor experiences with GPS technology, refer to GPS Outdoors: A Practical Guide for Outdoor Enthusiasts (Menasha Ridge Press).

THE HIKE PROFILE

In addition to maps, each hike contains a concise but informative narrative of the hike from beginning to end. Within the text you’ll find common hiking terms such as “rock ducks” or “cairns”—the small stacks of rocks left by other hikers to help mark the route. This descriptive text is enhanced with at-a-glance ratings and information, GPS-based trailhead coordinates, and accurate driving directions that lead you from a major road to the parking area most convenient to the trailhead.

At the top of the section for each hike is a box that allows the hiker quick access to pertinent information: quality of scenery, condition of trail, appropriateness for children, difficulty of hike, quality of solitude expected, hike distance, approximate time of hike, and outstanding highlights of the trip. The first five categories are rated using a five-star system. On the next page is an example.

The two stars indicate the scenery is somewhat picturesque. The three stars following indicate it is a moderately easy hike (five stars for difficulty would be strenuous). The four stars mean that the trail condition is very good (one star would mean the trail is likely to be muddy, rocky, overgrown, or otherwise compromised). The five stars for solitude mean you can expect to encounter only a few people on the trail (with one star you may well be elbowing your way up the trail). And the final three stars indicate that the hike is doable for able-bodied children (a one-star rating would denote that only the most gung-ho and physically fit children should go).

Distances given are absolute, but hiking times are estimated for an average hiking speed of 2 to 3 miles per hour, with time built in for pauses at overlooks and brief rests. Naturally, if you backpack in and stay overnight, you will need to adjust those times accordingly.

1 Wilson Trail

SCENERY:

DIFFICULTY:

TRAIL CONDITION:

SOLITUDE:

CHILDREN:

DISTANCE: 8.7 miles round trip

HIKING TIME: 4–5 hours

OUTSTANDING FEATURES: Predominantly flat with some hills and dales, wildflowers in spring, horned lizards, rock formations, view of the desert valley and the Salton Sea

Following each box is a brief italicized description of the hike. A more detailed account follows in which elements such as trail junctions, stream crossings, and trailside features are noted, along with their distance from the trailhead. Flip through the book, read the descriptions, choose a hike that appeals to you, and prepare for it accordingly.

Weather

Each of the four seasons occurs in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, with snow sometimes falling when it’s cold enough in the higher elevations, and spring showers bringing beautiful flowers. Of course, heat is what people typically associate with the desert—and it does get hot. Don’t hike in the summer months, when temperatures routinely exceed 100ºF. Also, be aware that flash floods, electrical storms, and dangerous winds are possible year-round. Know the expected weather before you go, and watch for changes. Even on moderate days in fall or spring, you’ll need to wear layered clothing as a safeguard. The temperature inside a canyon or within the walls of a gorge can dip much lower than that on an open trail in full sun.

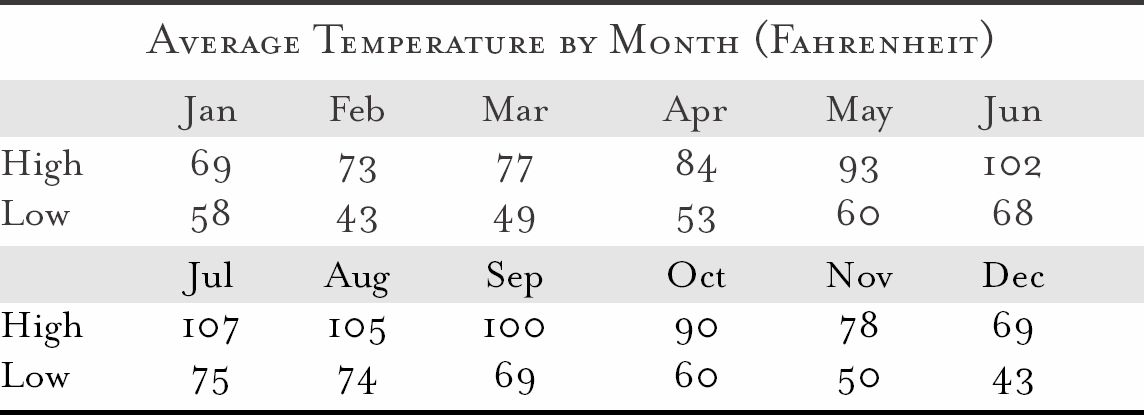

The average-temperature chart below refers to temperatures in Borrego Springs. As noted above, temperatures within different areas of the park itself can vary considerably, dipping well below or above those reflected in the chart. (According to locals, you can predict the high temperature for the day by taking the morning low and adding 30 degrees.)

In general, the desert recreational season begins in October, when the highs begin tapering down to double digits, and the lows are at or above 60. These temperatures make backpacking enjoyable in the fall. By winter, you’ll want to rethink tent camping, although with the right equipment, temperatures dipping into the low 40s at night are still manageable. By March, average nighttime temperatures begin to climb a little, and the days are also fairly mild, making this one of the most popular months for camping. April and May are still fairly mild but variable. And no matter what month you go, as mentioned above, be aware of impending storms and prepare for weather variations. Those who have spent time in the sometimes-unforgiving wilderness know that it’s better to overprepare than be caught off guard. Each year brings news of people who become lost or get caught unprepared in a storm. Injuries, heat stroke, and deaths do occur. Be prepared, avoid taking risks, and you won’t be another statistic.

Water

How much is enough? Well, one simple physiological fact should convince you to err on the side of excess when deciding how much water to pack: A hiker working hard in 90-degree heat needs about 10 quarts of fluid per day. That’s 2.5 gallons—12 large water bottles or 16 small ones. In other words, pack along one or two bottles even for short hikes.

Most of the water sources described in this book cannot be considered reliable. Only a few specific desert areas boast water flow all year-round, so don’t count on the presence of water. Simply put, not bringing an adequate water supply with you into the desert is foolhardy.

Even where water is perennial as noted herein, choosing to drink it comes with risks. Some hikers and backpackers are prepared to purify water found along the route. But even this method, while less dangerous than drinking it untreated, can be dangerous. Purifiers with ceramic filters are the safest. Many hikers pack along the slightly distasteful tetraglycine-hydroperiodide tablets to debug water (sold under names such as Potable Aqua and Coughlan’s).

Probably the most common waterborne “bug” that hikers face is giardia, which may not hit until one to four weeks after ingestion. It will have you living in the bathroom, passing noxious rotten-egg gas, vomiting, and shivering with chills. Other parasites to worry about include E. coli and cryptosporidium, both of which are harder to kill than giardia.

For most people, the pleasures of hiking make carrying water a relatively minor price to pay to remain healthy. If you’re tempted to drink found water, you should do so only if you understand the risks involved. Better yet, hydrate prior to your hike, carry (and drink) eight ounces of water for every mile you plan to hike, and hydrate after the hike.

Clothing

There is a wide variety of clothing from which to choose. Be prepared for anything. If all you have are cotton clothes when a sudden rainstorm comes along, you’ll be miserable, especially in cooler weather. It’s a good idea to carry along a light wool sweater or some type of synthetic apparel (polypropylene, Capilene, Thermax, or the like) and wear a wide-brimmed sun-protection hat. A hat with a flap that can be fastened up or let down to cover your neck keeps you protected as the sun travels across the sky.

Although rain gear is available and a good idea for those hiking in wet weather, I don’t recommend hiking in desert storms. The elements can be disorienting, flash floods can occur, and strong winds can rip even the hardiest of hikers off their feet.

Footwear is another concern. Desert trails can be slippery, rocky, and studded with nasty thorns. Waterproofed or not, hiking boots should be your footwear of choice. Ankle-high styles offer more protection against spiky vegetation and also provide more support. Sport sandals are popular, but they leave much of your foot exposed and therefore aren’t appropriate for desert hiking. An injured foot far from the trailhead can make for a miserable limp back to the car. Ditto for wet feet, so consult the individual hike write-ups, and consider waterproof boots.

The Essentials

One of the first rules of hiking is to be prepared for anything. The simplest way to be prepared is to carry the essentials. In addition to carrying the items listed on the next page, you need to know how to use them, especially the navigation items. Always consider worst-case scenarios such as getting lost, hiking back in the dark, broken gear (say, a broken hip strap on your pack or a water filter getting plugged), twisting an ankle, or a brutal thunderstorm. The items listed below don’t cost a lot of money, don’t take up much room in a pack, and don’t weigh much—but they might just save your life.

WATER: durable bottles and water treatment such as iodine or a filter

MAP: preferably a topo map and a trail map with a route description. I also recommend Diana and Lowell Lindsay’s Anza-Borrego Desert Region map for anyone trekking into the area.

COMPASS

MIRROR: this will help attract attention from airplanes in emergencies

BANDANA: another attention-getter (tie to the top of a creosote tree)

FIRST-AID KIT: a good-quality kit including first-aid instructions

KNIFE: a multitool device with pliers is best

LIGHT: flashlight or headlamp with extra bulbs and batteries

FIRE: windproof matches or lighter and fire starter

EXTRA FOOD: you should always have some left when you’ve finished hiking

EXTRA CLOTHES: rain protection, warm layers, gloves, warm hat

SUN PROTECTION: sunglasses, lip balm, sunblock, sun hat

OTHER ITEMS I OFTEN CARRY INTO THE DESERT:

A lightweight thermal blanket (a foil one is ideal)

A roll of duct tape

Rope (professional-grade rappelling rope is best)

First-aid Kit

A typical first-aid kit may contain more items than you might think necessary. The ones on the following page are just the basics. Prepackaged kits in waterproof bags (Atwater Carey and Adventure Medical make a variety of kits) are available. Though there are quite a few items listed here, they pack into a small space:

Ace bandages or Spenco joint wraps

Antibiotic ointment (Neosporin or the generic equivalent)

Aspirin or acetaminophen

Band-Aids

Benadryl or its generic equivalent, diphenhydramine (in case of allergic reactions)

Butterfly-closure bandages

Epinephrine in a prefilled syringe (for severe allergic reactions)

Gauze (one roll)

Gauze compress pads (a half-dozen 4- by 4-inch pads)

Hydrogen peroxide or iodine

Insect repellent

Matches or pocket lighter

Moleskin or Spenco Second Skin

Sunscreen

Whistle (it’s more effective than your voice in signaling rescuers because it doesn’t sound natural and is loud)

Hiking with Children

No one is too young for a hike, but take special care in the desert, with its cacti, other thorny plants, and severe weather. Most of the hikes in this book simply aren’t suitable for children. Fit children older than age 10 may be able to handle flat, short trails, but the lack of shade, remote location, and unforgiving climate make hiking with toddlers and infants inappropriate. Use common sense to judge a child’s capacity to hike a particular trail. A list of hikes that are suitable for children. Do read the individual write-ups even for those hikes, though. Then consider your own child’s abilities when making a decision.

General Safety

The desert can be a barren, dangerous place, but to those who take the time to prepare and explore this vast wilderness, the area reveals its natural treasure. Potentially dangerous situations can occur, but preparation and sound judgment result in safe forays into the remote desert. Here are a few tips to make your trip safer and easier.

ALWAYS CARRY FOOD AND WATER, whether you are planning an overnight trip or not. Food will give you energy, help keep you warm, and sustain you in an emergency situation until help arrives. You never know if you will have a stream nearby when you become thirsty. Bring potable water, or boil/filter water before drinking it from a stream.

WEAR STURDY SHOES, along with a hat and plenty of sunscreen.

NEVER HIKE ALONE—take a buddy with you out on the trails.

TELL SOMEONE WHERE YOU’RE GOING and when you’ll be back (be as specific as possible), and ask him or her to get help if you don’t return in a reasonable amount of time.

STAY ON THE TRAILS AND ROUTES DESCRIBED HEREIN. Most hikers get lost when they leave the path. Even on the most clearly marked trails, there is usually a point where you have to stop and consider which direction to head. If you become disoriented, don’t panic. As soon as you think you may be off track, stop, assess your current direction, and then retrace your steps back to the point where you went awry. Using a map, a compass, and this book, and keeping in mind what you have passed thus far, reorient yourself and trust your judgment on which way to continue. If you become absolutely unsure of how to proceed, return to your vehicle the way you came in. Should you become completely lost and have no idea of how to return to the trailhead, remaining in place along the trail and waiting for help is most often the best choice for adults and always the best option for children. If you have prepared well, brought supplies, and taken that all-important step of telling someone where you’ll be and for how long, staying in place won’t result in disaster.

BE ESPECIALLY CAREFUL WHEN CROSSING STREAMS. Whether you are fording a stream or crossing on a log or rocks, watch every step.

MAKE SURE YOUR CAR, TRUCK, OR SUV is in good shape before you go to the park, and check road conditions before you set out. If your vehicle breaks down, stay with it—it’s easier to find a vehicle than a person.

WHEN CLIMBING OVER BOULDERS, be careful where you put your hands. Be aware of the possibility of snakes. When you are climbing down big boulders, make sure you’re not sliding into an area you can’t climb back out of (bring rope, and never hike alone). Also, when moving over boulders, be aware that some may be loose, so tread carefully. And what looks like solid ground might just be clumped mud, meaning your foot will slip through to nothing underneath.

BE CAREFUL AT OVERLOOKS. While these areas may provide spectacular views, they are potentially hazardous. Stay back from the edge of outcrops and be absolutely sure of your footing; a misstep can mean a nasty and possibly fatal fall.

STANDING DEAD TREES AND STORM-DAMAGED LIVING TREES pose a real hazard to hikers and tent campers. These trees may have loose or broken limbs that could fall at any time. When choosing a spot to rest or a backcountry campsite, look up. When hiking through woody areas, be careful not to hook your pack or clothing on a stray limb. Getting “hooked” can throw you off balance and cause injury.

- KNOW THE SYMPTOMS OF HEAT-RELATED EMERGENCIES, and prevent dehydration (drink water even before you are thirsty). There are three heat emergencies you should be aware of and know how to handle:

- Heat cramps—painful cramps in the leg and abdomen, along with excessive sweating and feeling faint. Caused by the body’s loss of too much salt, heat cramps must be handled by getting to a cool place and sipping water or an electrolyte solution.

- Heat exhaustion—dizziness, headache, irregular pulse, disorientation, and nausea are all symptoms of heat exhaustion, which occurs as blood vessels dilate and attempt to move heat from the inner body to the skin. Get to a cool place and drink cool water. Get a buddy to fan you, which can help cool you off more quickly.

- Heatstroke—dilated pupils; dry, hot, flushed skin; a rapid pulse; high fever; and abnormal breathing are all symptoms of heatstroke, a life-threatening condition that can cause convulsions, unconsciousness, or even death. If you think a hiking partner is experiencing heatstroke, get him or her to a cool place and find help. (Note: Cell phones very rarely work in the park—you might find reception in spots near the main roads, but even then it’s not reliable.)

KNOW THE SYMPTOMS OF HYPOTHERMIA, or subnormal body temperature. Shivering and forgetfulness are the two most common indicators of this insidious killer. Hypothermia can occur at any elevation, even in summer, especially when the hiker is wearing lightweight cotton clothing. If symptoms arise, give the victim shelter, hot liquids, and dry clothes or a dry sleeping bag.

TAKE ALONG YOUR BRAIN. A cool, calculating mind is the single most important piece of equipment you’ll need on the trail. Think before you act. Watch your step. Plan ahead. Avoiding accidents before they happen is the best recipe for a rewarding and relaxing hike.

ASK QUESTIONS. Park rangers are there to help. It’s a lot easier to get advice beforehand and avoid mishaps away from civilization, where finding help may be difficult. Use your head out there and treat the place as if it were your own backyard. After all, it is your state park.

Animal and Plant Hazards

TICKS

Ticks are commonly found in brush and woody areas. Therefore, you are less likely to encounter them in desert areas than in other regions. Some hikes, though, do go through wooded areas, so be aware that ticks are present. Ticks, which are arthropods and not insects, need a host to feast on in order to reproduce. The ticks that light onto you while hiking will be very small, sometimes so tiny that you won’t be able to spot them. Primarily of two varieties, deer ticks and dog ticks, they need a few hours of actual attachment before they can transmit any disease they may harbor. Ticks may settle in shoes, socks, or hats and may take several hours to actually latch on. The best strategy is to visually check every so often while hiking; do a thorough check before you get in the car; and then, when you take a posthike shower, do an even more thorough check of your entire body. Ticks that haven’t attached are easily removed but not easily killed. If you pick off a tick while on the trail, just toss it aside. If you find one on your body at home, remove it and then send it down the toilet. For ticks that have embedded, removal with tweezers is best.

SNAKES

Four types of rattlesnakes inhabit Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. Always be on the lookout for snakes; if you see one, give it plenty of room and leave it alone. When snakes have the opportunity, they escape from sight before you are upon them. Because snakes sense vibrations, a hiking stick pounded along the ground as you walk gives them fair warning of your presence and allows them to slither off. This tactic is probably why I have never seen a rattler in the park—a fact that amazes almost everyone I tell. Countless others have shared their stories of encounters with rattlers in the desert, so I know they’re plentiful. But the only snake I’ve seen is the coachwhip, a non-venomous snake that nonetheless can give a nasty bite if provoked.

When hiking in rocky areas, be careful where you step or put your hands. Fallen leaves also provide a hiding place, so be careful as you walk through them. As with any wild animals, snakes are drawn to available water, so you may be more likely to encounter them near streams.

MOUNTAIN LIONS

In some areas of the park, you will see signs indicating that mountain lions (also known as cougars) are present. In my desert treks, I’ve seen lots of tracks, so I am always alert for the predators. Encounters with mountain lions are rare, but whenever you venture into an animal’s habitat, the possibility exists. If you do see a mountain lion, leave it alone. More than likely, it will want to get out of sight. Here are a few helpful guidelines for mountain lion encounters:

Keep your children close to you, or hold your child. Observed in captivity, mountain lions seem especially drawn to small children.

Do not run from a mountain lion. Running may stimulate the animal’s instinct to chase.

Do not approach a mountain lion. Instead, give him room to get away.

Try to make yourself look larger by raising your arms and/or opening your jacket if you’re wearing one.

Do not crouch or kneel down. These movements could make you look smaller and more like the lion’s prey.

Try to convince the lion you are dangerous—not its prey. Without bending or crouching down, gather nearby stones or branches and toss them at the animal. Slowly wave your arms above your head and speak in a firm voice.

If all fails and you are attacked, fight back. Hikers have successfully fought off an attacking lion with rocks and sticks. Try to remain facing the animal, and fend off attempts to bite at your head or neck—a lion’s typical aim.

POISON OAK

Although uncommon, poison oak does exist in the desert. The only hike included in this book where I’ve encountered this nasty plant is in Oriflamme Canyon. But conditions do change. Where water is present, you may find poison oak—recognized by its three-leaflet configuration—on either a vine or shrub. Urushiol, the oil in the sap of this plant, is responsible for the rash. Usually within 12 to 14 hours of exposure (but sometimes much later), raised lines and/or blisters will appear, accompanied by a terrible itch. Refrain from scratching, because bacteria under fingernails can cause infection and you will spread the rash to other parts of your body. Wash and dry the rash thoroughly, applying a calamine lotion or other product to help dry the rash. If itching or blistering is severe, seek medical attention. Remember that oil-contaminated clothes, pets, or hiking gear can easily cause an irritating rash on you or someone else, so be sure to wash not only any exposed parts of your body but also any exposed clothes, gear, or pets.

Tips for Enjoying Anza-Borrego Desert State Park

I’ve chosen to include some of the best and most popular areas in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, giving you an overview, then narrowing those regions to my favorite hikes. Within each write-up, you’ll find descriptions of area plants and perhaps a quirky detail or two about how they grow or how Native Americans used them. You’ll read information about specific birds and other animals, as well as a little bit of history if such information applies. I’ve also included some geological specifics and landmarks such as nearby mountains, historical sites, or the source of water you’ll find on the trail.

To get specific information before you go, visit www.parks.ca.gov or www.anzaborrego.statepark.org, or call the park at (760) 767-5311. Dropping by the Visitor Center, with its well-stocked bookstore, and getting guidance from rangers will also be time well spent, because knowledge and preparation can keep you safe—and being safe allows you to have fun. Here are a few more tips for enjoying your time in the desert.

• TAKE YOUR TIME ALONG THE TRAILS. Anza-Borrego Desert State Park is filled with wonders both big and small. Don’t rush past a bright-pink flower to get to that overlook. Stop and examine the beautiful swirled striations in a nearby rock, or notice the patterns etched into the sand by tiny footsteps. Let the sound of a rushing stream trickle joy into your mood, and don’t be so focused on getting to the hike’s end that you miss its middle. Short hikes allow you to stop and linger more than long ones—something about staring at the front end of a 10-mile trek naturally pushes you to speed up. That said, take close notice of the elevation maps that accompany each hike. If you see many ups and downs over large altitude changes, you’ll obviously need more time. Inevitably, you’ll finish some of the hikes long before or after the suggested times. Nevertheless, leave yourself plenty of time for those moments when you simply feel like stopping and taking it all in. Some of my most memorable conversations have been during impromptu stops with a friend along the trail.

• WE CAN’T ALWAYS SCHEDULE OUR FREE TIME when we want, but try to hike during the week and avoid the traditional holidays if possible. Trails that are packed in the spring, when wildflowers are at their height, are often clear during the colder months. Though the flowers aren’t as plentiful, you’ll almost always find some in bloom. If you are hiking on a busy day, go early in the morning; it’ll enhance your chances of seeing wildlife.

Backcountry Advice

Please practice low-impact camping. Adhere to the adages “pack it in, pack it out,” and “take only pictures, leave only footprints.” Practice “leave no trace” camping ethics while in the park.

Solid human waste must be buried in a hole at least 3 inches deep and at least 200 feet away from trails and water sources; a trowel is basic backpacking equipment.

These suggestions are intended to enhance your experience within the confines of this state park. Regulations can change over time; contact the park to confirm the status of any regulations before you enter the backcountry.

Trail Etiquette

Whether you’re on a city, county, state, or national park trail, always remember that great care and resources (from nature as well as from your tax dollars) have gone into creating these trails. Treat the trail, wildlife, and fellow hikers with respect.

• HIKE ON OPEN TRAILS ONLY. Respect trail and road closures (ask if not sure), avoid possibly trespassing on private land, obtain permits and authorization as required, and leave gates as you found them or as marked.

• LEAVE ONLY FOOTPRINTS. Pack out what you pack in. No one likes to see the trash someone else has left behind.

• NEVER SPOOK ANIMALS. An unannounced approach, a sudden movement, or a loud noise startles most animals. A surprised animal can be dangerous to you, to others, and to the animal itself.

• PLAN AHEAD. Know your equipment, your ability, and the area in which you are hiking—and prepare accordingly. Be self-sufficient at all times; carry necessary supplies for changes in weather or other conditions.

• BE COURTEOUS TO OTHER HIKERS, bikers, equestrians, and all those you encounter on the trails.