8 Sheep Canyon

SCENERY:

DIFFICULTY:

TRAIL CONDITION:

SOLITUDE:

CHILDREN:

DISTANCE: 2–10 miles round trip

HIKING TIME: 4–7 hours

OUTSTANDING FEATURES: Variety of waterfalls, massive and unusually shaped boulders, oases, and lush riparian environment

A daylong out-and-back hike from the third crossing parking area, or 2 round-trip miles if your four-wheel drive can make it to Sheep Canyon Primitive Camp. Whichever you choose, Sheep Canyon is a rugged trek holding picturesque settings at every turn. Abundant water cascades from massive boulder formations and shady caverns.

OPTIONS: Flat, sandy spots in the canyon’s wide areas make good campsites that don’t break the park’s rules about camping too close to water sources. Or make use of Sheep Canyon Primitive Camp, and then access the trailhead in the early-morning hours, when wildlife is most active.

Directions: From Borrego Springs, drive east on Palm Canyon Drive and turn left on DiGiorgio Road. Drive 5 miles till the pavement ends; then continue on the dirt road for an additional 5.6 miles to the large turnout on the left, just before the third crossing. If you cannot or choose not to drive all the way to this point, park at the first or second crossing, adding appropriate mileage to the hike (see the Coyote Canyon Introduction). In a four-wheel drive, it’s possible to begin the hike 4 miles from the third crossing at the Sheep Canyon Primitive Camp—cutting this hike by 8 miles round trip.

| GPS Coordinates | 8 SHEEP CANYON | |

| UTM Zone (WGS84) | 11S | |

| Easting | 548157 | |

| Northing | 3691995 | |

| Latitude–Longitude | N 33º 21’ 57.9924” | |

| W 116º 28’ 56.4475” |

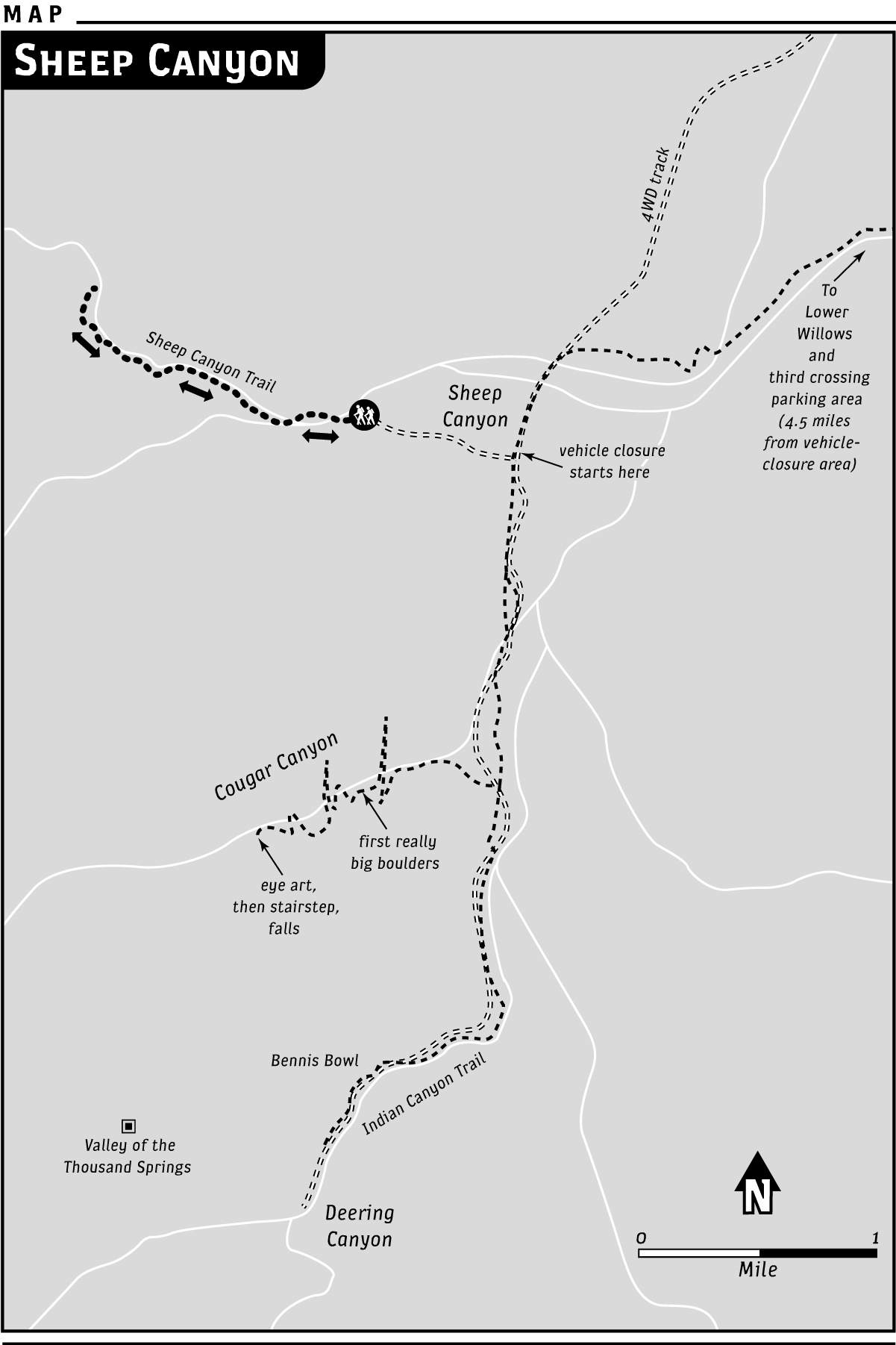

From the parking area just before the third crossing (see the Coyote Canyon Introduction), turn left and cross the stream, pass by the entrance to Lower Willows, and continue up the steep, rocky hill heading west. The rocky uphill section continues for about 0.66 miles before the road begins a gradual descent. On foot or by four-wheel drive, continue west on the Jeep road. It’s about 1.5 miles till you pass the spur road on the right leading to the Santa Catarina Spring historical marker. The road bends a little to the right. Continue along this dirt Jeep route, as directed by the “Sheep Canyon” marker sign. At just more than 2 miles, the road forks; follow the left split west toward a sign marked “Sheep Canyon Camp.” At approximately 3.8 miles from the third crossing, the route dips, crossing a wide, sandy wash. Turn right at the turnoff to Sheep Canyon Primitive Camp at 4 miles. There’s plenty of space to park here, or you can drive a short distance to the end of the official camping site, where you’ll see the hiking trail. We’ll call this the official trailhead.

From the parking area just before the third crossing (see the Coyote Canyon Introduction), turn left and cross the stream, pass by the entrance to Lower Willows, and continue up the steep, rocky hill heading west. The rocky uphill section continues for about 0.66 miles before the road begins a gradual descent. On foot or by four-wheel drive, continue west on the Jeep road. It’s about 1.5 miles till you pass the spur road on the right leading to the Santa Catarina Spring historical marker. The road bends a little to the right. Continue along this dirt Jeep route, as directed by the “Sheep Canyon” marker sign. At just more than 2 miles, the road forks; follow the left split west toward a sign marked “Sheep Canyon Camp.” At approximately 3.8 miles from the third crossing, the route dips, crossing a wide, sandy wash. Turn right at the turnoff to Sheep Canyon Primitive Camp at 4 miles. There’s plenty of space to park here, or you can drive a short distance to the end of the official camping site, where you’ll see the hiking trail. We’ll call this the official trailhead.

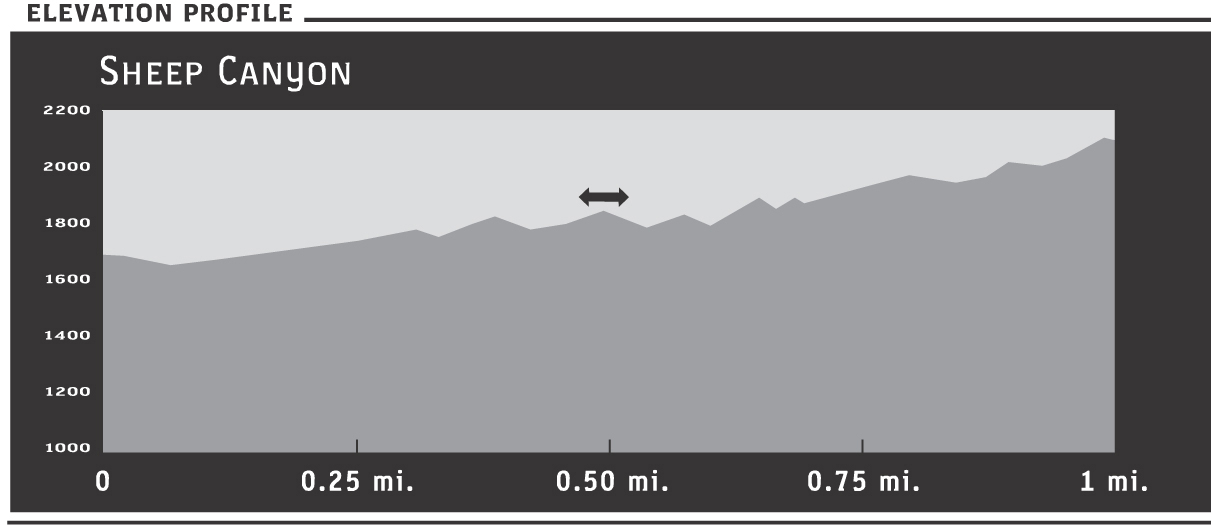

Head past the metal horse tie into the canyon via a narrow path to the right, which takes you to sand dunes running between stream fingers. The trail moves toward the right (north) side of the canyon, crossing the stream or keeping it just to the right (depending on the water’s flow). Generally, if you stay toward the right, you’ll be fine. The stream bends to the right, and you’ll note a canyon fork coming in on the right—which is where you want to go. The south fork of Sheep Canyon is straight ahead, but going there is not recommended—it’s easy to get caught in inescapable “bowls” formed by massive rocks.

Turn right and generally follow the stream, crossing so the water is on your left now. You’ll need to climb over embedded boulders that pave the path (fairly easy, with some handholds). Sycamores and willows encroach, with gentle breezes adding to the sound of trickling water.

At 0.2 miles, an idyllic waterfall comes into view, tumbling around a huge rectangular boulder that’s an anchoring point for a gnarled cottonwood, several sycamores, and palms. Pass on the right, climbing over boulders and using trees for handholds. Or squeeze by on the left, without as much vegetation to hang on to.

Look for the signs of ant-lion larvae in small sandbars gathered atop and alongside the boulders. The tiny, cone-shaped pits are the voracious ant lion’s way of trapping the smaller insects on which they feed. As adults, the larvae form cocoons from which they later emerge as lacy-winged flying insects.

You’ll pass beneath oak trees, reveling in their dense shade as well as that of sycamores and palms. The rock canyon wall rises on your left, with the fleshy, succulent chalk live-forever clinging like pale-green bows. Cross the stream as many times as you need to, noticing baby cottonwoods by the hundreds. Climb encroaching boulders as necessary, careful where and how you step—snakes could be resting in the fallen leaves. Also be aware that what looks like solid ground may not always be: piled rocks covered in leaf litter can hold hollows. One misstep recently sent my foot—whoosh—down an unseen hole. In an instant, my leg had disappeared into a cavern formed by piled boulders.

At about 0.33 miles, a large waterfall cascades over steplike rocks. From here, you’ll need to cross and recross the stream as it meanders down the canyon. Just follow the lay of the gorge, which reaches a 25- to 30-foot waterfall at 0.4 miles. The water flows from some large angled boulders, arranged to form a wet cavern below. Pass this boulder-crowded area by climbing a little on the right side of the canyon, angling back toward the steam, then crisscrossing back and forth over the sparkling water—perhaps with tree frogs hopping.

About 0.5 miles from the trailhead, boulders again encroach, making it necessary to go right, then arc back toward the stream. Here, the mother of all boulders, shaped like the great stern of a ship, comes into view. A huge, gnarled sycamore blocks passage on the right, so to go any farther, you’ll have to climb up around the boulder on the left. This is difficult, but worth it. Just a few yards past the ship boulder is a large, cool cavern, its ceiling formed by another massive boulder. Enjoy the shade and the echoes of water tumbling in, around, and through piled rock. Sunlight reaching through crevices causes a dancing reflection on the stone ceiling in this cool, dripping space.

From the large cavern, the canyon comes to a fairly quick end. Heading to the left, you can scramble carefully up the rocks to a saddle for a perched view down the canyon if you choose. In warmer weather, leaving behind the watery caverns and shady oaks in favor of a sweaty rock climb won’t often appeal. Retrace your steps back down the valley, careful as always to avoid a fall—and to enjoy the delightful sights and songs of nature.