Possessing a multifaceted picture and a powerful magnetism, which attract both admirers and critics alike, Slim is not immutable to either criticism or praise. He takes advantage of his celebrity status to support causes like stopping global warming. When the Secretary General of the United Nations Ban Ki Moon invited Slim to form an advisory group on climate change, he eagerly jumped aboard.

It is unnecessary to list the amount of frivolous magazines that make satisfactory accounts of entrepreneurs and their wealth. As others have said, when one measures success in terms of money, it’s boring and tiresome.

Slim’s fortune is equal to six percent of Mexico’s GDP thus making him the richest man in Mexico and among the world’s wealthiest men. Although he has donated about a quarter of his fortune, he said it makes him uncomfortable to be thought of as Santa Claus.

“Problems are not solved by handing out donations. Charity doesn’t consist in giving, but rather in doing and resolving,” he said. “Poverty is not eliminated with donations, but with education and employment. We have to do things in life and prove to be efficient, compassionate and responsible with the management of our wealth. It does not interest me to construct a monument in my honor nor to be given awards for what I do. My concern is not being high or low on the Forbes list. My concern and my occupation is that my companies are efficient, that they develop, and have appropriate strategies that can compete with anyone.”

Throughout his life, Slim has been surrounded by friends. But then again, everyone wants to be friends with such a powerful man. Some of people want to make their friendship with Slim known. Writers, poets, painters, singers, businessmen or politicians; all of them want a chance to say they know Slim. Presidents of all latitudes seek him out. Statesmen of America and Europe solicit his presence. The world’s most important businessmen meet with him. The rectors of public and private universities ask him to give seminars “to enlighten” people, and forums invite him to present his vision of Mexico and its present and future reality. Several winners of the prestigious Nobel Prize have been entertained in his home. Characters from all corners of the world surround him.

Fortune has been kind to Slim in every way. In spite of it or because of it, the engineer continues to greet his employees and partners with the same taste and appreciation. He is interested in their lives and listens when time allows for it. He has very close friends from all walks of life.

The concept of friendship is an interesting one. In the early history of human civilization, people were called friends by way of their honorable treatment of pharaohs, kings and court officials. There weren’t “friendships” as we know them. People who intervened in a friendship could be punished with death. Perhaps the most symbolic tale of friendship is that of the patriarch of Judaism, Abraham with God. The conqueror Alexander the Great, who by twenty-five had traveled throughout Europe, Asia and half of Africa, built his empire alongside his seven major friends, whom he called “generals.” There is also the example of two great thinkers of the mid-nineteenth century, Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. Despite not seeing eye-to-eye in terms of philosophy and history the first time they met, after spending time in a German tavern, they became great friends and together they made history in the realm of political science.

Thus in the life of every successful man; friends are a cornerstone. For Slim, friends are a basic necessity.

His character, nature, vision and business acumen have not only impacted countless characters, but he has done so by way of selfless vocation. His multifaceted personality has dazzled men of power. The most powerful presidents (Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama) and political leaders such as Felipe González, the legendary Mikhail Gorbachev and Fidel Castro have all praised him, as have high-flying intellectuals and writers like Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes and Octavio Paz. Journalists are no exception (some of whom claim to speak only with presidents) like Julio Scherer Garcia, who became a partner in Proceso.com, subsidiary of Proceso magazine. His nature is charismatic. Since Slim was very young, he worked with old legends and symbols of wealth such as Carlos Trouyet and Manuel Espinosa Iglesias. He has rubbed shoulders with the Rockefellers and Bill Gates, and he is friends with an infinite number of political and noble personalities such as Prince Charles. Every year, he is on the list of the one hundred most influential men in the world.

His power to attract attention is fascinating. Both left- and right-wing personalities are drawn to him as though he were a charismatic leader or an imam.

He is not infallible however; malice finds him. Some critics tried to link him to the controversial former president Carlos Salinas de Gortari,, but Slim denied any such partnership. The sharpest journalists have set it straight: Salinas and Slim share a name (Carlos and Charlie) but that is all.

Columnists have called him a survivor because of the crisis of the eighties. In addition to King Middas, he has also been called a patron of intellectuals, a bargain shopper, an art hoarder, the best representative of capitalism, a monopolist, a figurehead, a beneficiary of Salinas, an ambitious speculator, the Conqueror and many other adjectives. But he has also been the strong suit of the government when it has been necessary to explain the crisis in major financial centers or to negotiate credit for the country.

A counterpart of business and money, Slim’s alter ego is immersed in culture, sports and philanthropy. Collector, philanthropist and patron, politicians of all stripes praise him. He is friends with priests and atheists, a lover of filmmakers; he is a scholar and has published articles like other economists. As a lover of the so-called “king of sports,” baseball, he is erudite and has published articles using the game as an example of how he sees parenting and the positioning of heirs. He also has a love for boxing and boxers, most of them world champions. Many Olympic athletes receive scholarships from his foundations to support their development. The same is true of academics and intellectuals, many of whom come from various countries attending the Centro de Estudios Carso (the Carso Study Center). Here, they can do specialized research, accessing the invaluable collection of over 80,000 documents and nineteenth-century books on the history of Mexico.

The advisory board of the study center is composed of Enrique Florescano, Teodoro González de León, Patricia Galeana, Miguel León Portilla, Carlos Martínez Assad, Enrique Krauze, Carlos Monsiváis, Fernando Solana Morales, Enrique González Pedrero, Ricardo García Sainz and Manuel Ramos Medina, among others.

For decades, Slim has had contact with many of the most important intellectuals in order to promote the study of the history of Mexico. Slim has a special affection for the historian José Ezequiel Iturriaga Sauca, whom he simply calls “Don Pepe.” Another character with whom Slim has great affection is the humanist Ernesto de la Peña. “A friendly person with a great soul,” Slim calls him.

In the eighties, when he began to project himself as the guru of business, Slim’s circle attracted the most diverse intellectuals and he forged an intimate friendship (which later became estranged) with the journalist and writer Fernando Benítez. He met Benítez at his brokerage firm Inverso Bursátil. The tycoon had received a coded gift from a friend and was intrigued to understand its contents. Benítez helped decipher it and so began their friendship.

It was Benítez who introduced him to Carlos Fuentes, Hector Aguilar Camín, Carlos Monsiváis, and Carlos Payán. All of whom were attracted to Slim, as was writer Guillermo Tovar y de Teresa, the historian Enrique Krauze and the Nobel Prize winner Octavio Paz.

Slim was one of Octavio Paz’s few friends. “They were very close friends; they truly cared for one another,” said painter Juan Soriano, suggesting that Slim was “perhaps the poet’s best friend.” In December 1997, when at the age of eighty-three, the poet was confined to a wheelchair because of illness, he spearheaded an austere ceremony with President Ernesto Zedillo to announce the creation of the Fundación Cultural Octavio Paz (the Octavio Paz Cultural Foundation). Slim was one of the first to financially support the institution and along with another group of large employers like Emilio Azcarraga Jean, Alfonso Romo, Manuel Arango, Antonio Ariza, Bernardo Quintana, Carlos González and Fernando Senderos Zalabagui, among others, gathered in the Alvarado House on the street named for Francisco Sosa de Coyoacán.

When someone asked the writer Carlos Fuentes why Slim seeks the company of intellectuals, the author of Where the Air is Clear said that Slim “does not search us out; we enrich each other. We are attracted by his freshness and spontaneity.”

Of his relationship with former Spanish president Felipe González, Slim said they never dealt with matters of business, “It’s not our thing.” Their friendship is more intellectual and spiritual. Slim recognizes him as a statesman: “Felipe is a universal type.” Whenever they meet, they talk about new society and the paradigms of the new civilization. “One of the things that interest us is the challenge of how to solve our country’s problems,” Slim said. “These are the issues Felipe and I talk about.”

Fernando Benítez told a story about his friend’s simplicity when the two drove the Mayan route of southeastern Mexico. They both had to improvise in Yaxchilán, where they found some tents and slept on the floor.

In 1996, Benítez wrote an article in the newspaper La Jornada entitled Slim. In it, he extols the virtues of the billionaire:

More than twelve years ago, I met Slim and since then we have been friends. A few months in, Carlos, with the greatest tact, gave a large sum of money to Guillermo Tovar y de Teresa, José Iturriaga and me. Slim knew that we were master researchers of our history, always poorly rewarded for our work so he helped us in our endeavor.

Carlos was a remarkable entrepreneur and art lover. We took an unforgettable trip to the ruins of Palenque, Yucatán, Yaxchilán and the palace painted by the Lacandon17 people. We spent beautiful moments together.

Carlos, along with other partners, bought the old golf club in Cuernavaca, which was about to be divided into many plots and was the only real green space in the city. He admired the way I cared for trees, especially the ahuehuetes18 that were at the point of extinction, and he dug a small lagoon to save them. He told me: “If we did the same in Chapultepec, then the wonderful trees would not die.”

At noon we ate at tables decorated by delicacies provided by his wife Sumy. At night we talked in the club lounge where General Calles played poker. It was on one of these nights that we read the magazine Forbes, which included Carlos. When I saw that he had two or three billion dollars, I yelled, “I never thought I’d be friends with such a rich man!”

Last Sunday, I was surprised to see that Carlos conceded to be interviewed by the magazine Proceso. The reporter, Carlos Acosta Córdova, is very astute and unforgiving. Carlos appeared on the cover with a title that read: “Salinas is Your Partner?”

“I have no political associates … I do not need any,” answered Slim. The city is full of rumors and uncertainties. Carlos Slim is rumored to have made his fortune in times of Salinas; rumored on Colosio, Ruiz Massieu, Muñoz Rocha, the Attorney Lozano Gracia and from the tragic moments in which we live. The rumor is very old and sometimes dangerous. In the cafés they are always talking about candidates and who would be the next president or nominee.

Hardly anyone knows that Carlos was born rich. His father had a prosperous business near the National Palace and he sometimes bought old colonial houses that were worth more for their land than for their architecture. Carlos studied to be an engineer and with his inheritance, he built a multi-story building in which he lived in an apartment with his wife and children. Extraordinary financier, he began buying several businesses and factories.

Some Mexicans criticize him without knowing the Teléfonos de Mexico system. The modernization of the company demanded the termination of many employees, but Carlos did not fire anyone. Instead, he exercised a mandate to teach them new systems that would bring them up to the new standards. He does not fear competition though there are two more long-distance companies in the world: ATT and MCI. They operate in large cities, but are not interested in the villages and towns in Mexico. Instead, Telmex phone has taken 22,000 villages in Mexico.

Carlos criticized Proceso for attacking him. The reporter said he had collected opinions from various sources, including Cuauhtémoc Cardenas. Carlos said that the reporter tried to insult him due to his ignorance or bad faith.

Though I am not very familiar with the economy, I will quote some of the concepts that Carlos said in his interview with Proceso:

“It is remarkable that six years after the privatization of Telmex, when the competition had begun, a mass of criticism started up against me, and mainly against Teléfonos de Mexico.”

Denying that it was a spontaneous idea, he said, “The Grupo Carso started in 1965; in 1976 we already had Galas, which in the previous twenty years was a major advertising company in the country. Since 1981, we acquired Cigarrera La Tabacalera Mexicana (CIGATAM), which is certainly very important: it produces Marlboro cigarettes, Delicados, Lights, Benson, Baronet, and Commander. Then, in 1984 we purchased from Manuel Espinosa Church one of their packages of bank assets, which included 100 percent of Seguros de México, worth US$55 million. It was odd that a stranger could make a purchase of US$55 million, no?

“We do not have political partners. The Grupo Carso did not have nor will ever have political partners. That is clear and always will be.

“My relationship with [Carlos Salinas de Gortari] was cordial—I saw him four times. [He was] very respectful as secretary and as president, but regarding favors, [he did not grant me] even one. An example: in the late sixties, early seventies, I bought some land in the foothills of Xitle. During the Salinas government, they expropriated it from me and to date, I have not finished paying it off. I was never given any favors and in the businesses that I do, I don’t need any favors.

“I think the employer should work in their businesses and be oblivious to plans and projects of political concern. I do not belong to any political party nor do I want to belong to one.

“My personal image or that of Grupo Carso does not concern me. In the case of Telmex, its image is important for the time being given our competition with large corporations. With each falsity that is claimed, they are looking to discredit Telmex so that the transnational companies can penetrate our country.

“Among the wealthy as well, what matters is not how much you have, but what you do with what you have.”

Carlos does not care about wealth, but how it should be spent. He dislikes talking about the doctors he enlists for poor patients or the 12,000 college students to whom he has given awards and scholarships (5,000 of them earn a minimum monthly salary and have a computer with Internet access). Among many other charities, Slim provides funding and financial aid to prisoners—prisoners who are incarcerated for being poor, not delinquent—and can’t pay their way out of prison. He also helps healthcare institutions, as well as centers for research and prenatal care. He promotes feeding programs for low-income mothers and supports the training of physicians. He also supports museums and book production. He continues such funding with about MS$120 million annually.

I will end with the last question the reporter asked Carlos Slim: “What underlies all this seeming generosity? Any slope in consciousness? Because you could easily not do any of this social work.”

To which Carlos answered, “No, nothing of that sort. I have total and absolute conviction, without a doubt. I am convinced that we must do it. I like it and want to do it. Also, I think when you leave this world you can’t bring any of your material possessions with you. So, in some way, I am like a temporary manager of my wealth because I won’t be able to bring it with me to the afterlife. You can have whims and commit mistakes, but in the end of it all, what for? Therefore, I believe we must do whatever is important during our lives because you can’t do it after.”

The concept of philanthropy is not a new one. The Roman Flavius Claudius Julianus, who invented the concept of charity, coined the term “philanthropy” with religious use by imitating the Christian zeal to paint paganism as a Roman religion. Now, this phenomenon is referred to by some as “philanthropi capitalism.” To be the richest company in the world, or the richest man, you are managing the “profitability” of said wealth and you must make millionaire contributions.

In countries like the United States and Spain, there is a long tradition of philanthropy. Boston College will soon have a Study Center on Wealth and Philanthropy, and Madrid has established the Spanish Association for the Development of Corporate Philanthropy.

In Mexico, some millionaires also invest in poverty. Given the growing social polarization between the mega rich and the poor, some have focused their activities on those who are less fortunate, including the creation of the Mexican Center for Philanthropy. Universidad Iberoamericana, which also receives funding from magnates, created the head of the department of philanthropy aimed at researchers and developers who want to devote their research to this subject. Other institutions like the Fondo para la Asistencia, Promoción y Desarrollo19 I.A.P. (FAPRODE) created the MIRA project with the aim of articulating a culture of philanthropy among broad sectors of Mexican society.

Since then, there have been those in power who have sought to benefit from philanthropy, as happened with Vamos México; created by the initiative of former president Vicente Fox’s wife. Marta Sahagún invited Slim to join as an honorary member along with other employers, including Roberto González Barrera, Fernando Senderos, Alfredo Harp Helú, Ricardo Salina Pliego, Emilio Azcárraga Jean, Roberto Hernández, Lorenzo Zambrano, Manuel Arango Arias and María Asunción Aramburuzabala.

Slim invests millions in philanthropic activities annually. He said he does not act out of vanity, neither does he hope to claim that his name remains on a plaque generation after generation, but rather that he constantly seeks concrete solutions for education, health and combating poverty.

His name stands out among the leading philanthropists in the world next to Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, George Soros and the descendants of Sam Walton.

As a benefactor of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, Slim has belonged as a UNAM Foundation Board member since its inception. Among other members are the rector José Narro Robles, Rafael Moreno Valle Suárez, Alfredo Harp Helú, Bernardo Quintana, María Teresa Gómez Mont, Luz Lajaous Vargas, Abedrop Dávila, Cesar Buenrostro Hernández, Julia Carabias Lillo, José Carral Escalante, Alfonso de Angoitia Noriega, Juan Francisco Ealy Ortiz Martínez, Juan Diego Gutiérrez Cortina, Jaime Lomelín Guillén, Guillermo Ortiz Martínez, Fernando Ortiz Monasterio de Garay, José Octavio Reyes Lagunés, Francisco Rojas, Olga Sánchez Cordero, Salvador Sánchez de la Peña, Federico Tejado Bárcena, Jacob Zabludovzky, José María Zubiría Maqueno, Alfredo Adam Adam, Raúl Robles Segura, Francisco Suárez Davila and Araceli Rodríguez Fernández.

When Francisco Barnés de Castro was rector, the highest seat of learning, he publicly acknowledged Slim and honored him with a medal for his support of the UNAM Foundation. He had previously awarded grants totaling MX$40 million. “I wish there were more Slims who would donate generous grants to financially support more students,” the rector explained.

The universities that make up the Corporación Universitaria para el Desarrollo de Internet20, A.C. (CUDI), headed by Slim’s Teléfonos de México and other telecommunications and technology firms such as Nortel Networks, Marconi Communications and Cabletron Systems have donated high-speed networks worth tens of millions of dollars to promote higher education in the country.

Slim also donated refurbished computers to Technology Museum of Federal Commission for Electricity for the benefit of students in public schools who come daily to take advantage of the computer lab.

With the support of his businesses, the Grupo Carso mogul gives thousands of scholarships to students. Through the Telmex Foundation, he awards thousands of computers each year to a large number of trainees. In addition, in order to prepare his Telmex employees, he created the Instituto Tecnológico de Teléfonos de México21 (Inttelmex).

After Slim bought Teléfonos de México, his wife Soumaya Domit, along with the labor union at the company, created the Fundación Telmex22, whose social activities have provided support to victims of natural disasters and assistance to disadvantaged students across the country. In the support of medicine, he created an organ bank in Mexico. His son Marco Antonio Slim Domit chairs the board of the National Transplant Council (CONATRA), which has a Web site and a phone line that provides information about transplants. The Board of this institution, at its inception, consisted of the young entrepreneurs Olegario Vázquez Aldir, Alejandro Soberon Kuri, Michael Aleman Magnani, Emilio Azcarraga Jean and Lili Domit.

Since his wife Soumaya undertook the task of social assistance, with support from the Telmex Foundation in the years 1996-2011, emphasis was placed on these achievements (only a few of many): 6,781 organ and tissue transplants, 629, 965 surgeries, and 242,486 student scholarships. They have donated 256,864 bicycles to students from rural zones with poor resources and more than 127,750 eyeglasses to people with vision problems. In addition, they have contributed to humanitarian aid and financial support in natural disaster zones. From 2007 to 2009, the Foundation made possible 2,391 new organ transplants, particularly kidney, cornea, liver, heart, skin and lung.

Since 2007, the support of the Carlos Slim Foundation and the Telmex Foundation has grown exponentially to the degree of around US$10 billion for altruistic purposes in health, education, sports, culture, environment, social finance, justice, support for social institutions, the NGO’s restoration of the Historic Center of Mexico City, and funds for possible natural disasters.

Soumaya and son Carlos Slim Domit are also members of the board of the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Salvador Zubirán Nutrition.

In its national fundraising, the Mexican Red Cross was a beneficiary of the Telmex Foundation. Support was given in the form of an advertising campaign in mass media and the donation of US$500,000 along with ambulances for extremely poor and unprotected zones.

Slim created the Fundación Carso23, A.C. (originally under the name Asociación Inbursa, A.C.), in June 1986. The group’s principal activities are to start, promote, sponsor, fund, or establish and maintain libraries, newspaper libraries, museums and exhibitions, conferences and congresses, support hospitals and orphanages, as well as help people in need. He has encouraged donation because since 1989, all donations are tax deductible. In order to increase his capacity to support the association, he has reinvested the surplus of financial resources in Mexican securities. Irrevocably, income from donations and the proceeds generated by their investments have been earmarked for social, cultural and charitable organizations.

Slim was instrumental in the creation of the Museo Soumaya in 1994. Since its founding, a number of cultural and social projects have benefited from the financial support of Carso, A.C. Among them are the Mexican Red Cross, the Mexican Association of Aid to Children with Cancer I.A.P., the Association of Friends of the Metropolitan Cathedral of Mexico, A.C., the Music Academy of the Mining Palace, the Mexican Health Foundation, the Mexican Center for Writers, A.C., and UNAM Foundation, S.C., and the Children’s Hospital of Mexico Federico Gómez.

In 1988, a year before her death, Soumaya Domit was awarded the Philanthropy Award for her social work with marginalized groups.

Through the justice program of the Telmex Foundation, intercessions were made for the release of unjustly imprisoned indigenous people, as happened with sixty Zapatista prisoners in Chiapas who were accused of various crimes. Each year, the foundation supports nearly ten thousand people who commit petty crimes or who are victims of the abuse of power.

This program is operated by the Telmex Foundation in collaboration with the Fundación Inbursa. The main purpose of this program is to support poor people who are accused of committing a criminal act and who are deprived their freedom in different prisons in the country. In order to be granted their freedom, they must pay the bond or guarantee to repair the damage, but they cannot access the funds because they do not have the necessary resources. Fundación Telmex works in conjunction with the Office for the Development of Indigenous Peoples of the Presidency of the Republic.

Slim also participates in the Chiapas Fund along with other business groups in the country to boost economic recovery and contribute to reconciliation of the state. “There is no better investment than fighting poverty,” Slim said.

From his very personal perspective, Slim said of the problem of marginalization:

There is no doubt that in addition to moral or ethical connotations of trying to eliminate poverty, there is also a fundamental economic sense that we should all consider. There is no better fight than the one we are fighting against poverty; it is the best investment one can make in society (or even neighboring societies). To eliminate ignorance is to strengthen markets, develop domestic demand, and improve living standards. This is what I pointed out in Europe, where the countries that are lagging behind are supported by those that are far more advanced. At the moment, Mexico can resolve this problem fairly quickly, and our growth will be fuelled. We must start with a mother’s nutrition during pregnancy, care of children at birth, infant feeding in the early years (a time when the brain grows four times its size), child health, and education. They are the fundamental elements. When speaking of this new civilization in which it is much easier to create wealth, it is paradoxical that there would be more poverty. No doubt one of the needs of any country is to bring its population into the economy, to modernity. Poverty is a social, political and economic burden. When I talk of addressing the domestic economy, I mean that which I just explained.

Slim acknowledges that the funds given are not sufficient to eradicate poverty. That is why he has made alliances with companies and groups from other countries to support poor people with microcredit. For example, the Slim Foundation and Grameen Trust (a not-for-profit NGO), an international affiliate of Grameen Bank, signed an agreement to provide credit lines to people in the poorest areas of Mexico who are excluded from the international banking system and the support provided to them is made with interest rates well below any bank.

This project began in late 2008, with a capital of US$45 million driven by Slim and Professor Muhammad Yunus, with the Grameen Bank. They jointly received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for their work against poverty around the world.

He has done the same by supporting the Clinton Foundation. Slim joined with Frank Giustra, a businessman from the mining industry in Vancouver, Canada, and each agreed to contribute US$100 million to the program named the Clinton Initiative for Sustainable Growth. To a large extent, Slim’s contribution to this project will target Latin America. Through his role as former president of the United States, Bill Clinton has launched several campaigns, including one for AIDS and another to fight childhood obesity.

His philanthropy goes beyond any border. Slim has devoted more than US$2.5 million to the actions of Impulsora del Desarrollo y el Empleo en América Latina24 (IDEAL). IDEAL’s foundation aims to address the poorest families in the region with particular emphasis on problems of malnutrition, maternal and child health research and the environment.

His philanthropic work has not gone without recognition. For example, in a ceremony headed by President of Mexico Felipe Calderón, the Panamanian First Lady Vivian Fernández thanked Slim for his philanthropic support of her country and all of Latin America. She described him as “a human being that is above material success.”

But not all that is said about him is praise. Slim has been criticized for the way in which he exercises his monopoly. For example, a dissenting voice on Slim’s work is Denise Dresser, a contributor to the magazine Proceso. In an article entitled “The Two Faces of Slim,” she wrote that while his philanthropy should be applauded, we should be suspicious of his motivation. She writes that we should question what inspires the tycoon to seek to “appear as a virtuous man at a relatively low cost.” Slim’s philanthropic efforts, Dresser asserts, are to “clear his name through a legacy that no one could question,” especially when his efforts led Bill Gates to donate US$31 billion of his personal fortune and create the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and led Warren Buffet to also donate US$27 billion.

Dresser maintains that Slim is a conditional philanthropis t. “Philanthropy for profit that runs counter to what he supposedly seeks to promote: altruistic donations and selfless contribution. To develop oneself based on philanthropic work would be the exact opposite of what has made Bill Gates who he is,” she wrote. “Gates donates shares of Microsoft to the foundation he created and relinquishes control of them so that his donations are not tied to the Gates Foundation, to the performance of his company, or to obtaining government contracts. He donated money to polish his reputation. There is nothing wrong with that because he never used it to advance himself or his business. His philanthropy has never been linked to the return for more money. And he never put together a philanthropic scaffold in which generosity depended on the government’s willingness to let him venture into other areas of economic activity. Slim aims to give, however, he stands to gain even more.”

In a completely different light, former President Bill Clinton lends the following as his perception of Slim’s philanthropic spirit as founder of Carso. “Slim is one of the world’s most important philanthropists even though most people have never heard of his humanitarian activities,” Clinton said. “He owns stock in more than two hundred companies that employ more than 200,000 people in Latin America and beyond. He has used his resources to help develop the communities where his businesses are located. In his own country, Mexico, he has personally supported more than 165,000 young people in attending university, paid for numerous surgeries, provided equipment for rural schools, and covered surety bonds for 50,000 people who were entitled to their freedom but could not afford it. He recently created the Carso Institute for Health and designed it to provide a new approach to health care in Mexico. He has US$4 billion of investments ready to be spent towards the promoting of education, health and other great challenges, and has recently announced an additional US$6 billion investment in several programs, including his Telmex Foundation.”

Juan Antonio Pérez Simón, collaborator and one of Slim’s closest friends, exalts the qualities of the philanthropist and patron. “It is always important to know what your limits are, because you can have a foundation and say yes to everything. I think that Slim has done very well. There are many foundations that do charitable acts, but they will always reach their limit,” he said. “But when it comes to charity, support should be endless. Carlos has been charitable in a very organized way and that is how he always does things. His biggest concern has always been social problems. He is a man of constant work and he is brilliant, but it is his consistency that is the formula for success. Another of his virtues is his honesty, which is not easy to find. He is an honest man, dedicated to a mythical business to which he devotes all his time. For him, honesty is consistency. It goes beyond what you perceive; it is transparency. Moreover, he is also a great scholar and researcher; he can learn or take a lesson from anywhere. Carlos will not issue an opinion of value if he does not have a deep knowledge of the subject. He must conduct interviews with fifty people or read two-hundred books before he will deliver judgment on the matter.”

When Salinas de Gortari took office as president in the midst of challenges that portrayed him as an “impostor,” his special guest, Fidel Castro, was dazzled by Slim.

Salinas was the second youngest president in the history of Mexico, only after General Lázaro Cárdenas, who came to the first legislature of the country at thirty-nine years old. Salinas came to power amidst allegations of election fraud of massive proportions.

Slim met Fidel Castro with other politicians, intellectuals and academics while enjoying his stay in Mexico City for a meeting with wealthy businessmen. The legendary commander was interested in the character of whom many spoke so highly. The meeting took place in the Lomas de Chapultepec at a dinner that lasted until dawn. The host Enrique Madero Bracho, president of the Mexican Business Council for International Affairs, invited a select group of businessmen. Slim Helú was there and attracted the attention of the Cuban Revolution leader. Between toasts, Madero Braco did not hold back emotion and praise and lavished his special guest. He said, “Commander, if you were in Mexico, you would be a great entrepreneur. You have the talent to be.”

To which Castro replied, “Well, boy, I am an entrepreneur, but of the State.”

Slim, who was already a celebrity, addressed the issue of external debt and captured the attention of the commander. Castro listened without blinking. Slim seduced him with his chatter. The tycoon discussed the need Mexico had to keep its credit abroad and support the modernization of the country. Castro interrupted his interlocutor by bluntly saying, “Do not repay the debt. It is unpayable and uncollectable.” The Cuban’s argument was that the country had an excess of interest, which they considered a tribute to the US Empire and so there was no justification to continue to pay the capital.

One of Slim’s comments was that Mexico, in order to resolve much of its debt, had ventured into a new strategy: to exchange debt for shares of Mexican companies. Through this system, it was buying cheap debt because the market was at half its value. As examples, he gave the cases of some Central American countries that had paid their debts to Mexico through swaps.

This pattern made sense to Castro, who seconded Slim’s notion and accepted that several governments were already following such a strategy.

Similarly, Slim has attracted leftist representatives like Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Pablo Gómez, Rolando Cordera Campos, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas and Porfirio Muñoz Ledo.

Other prominent intellectuals have also succumbed to the tycoon’s seduction. Many of them have been dazzled by the money shown at Slim’s parties, like with the wedding of his daughter Soumaya Slim Domit, at which the following were all in attendance: former Spanish President Felipe González, General Enrique Cervantes Aguirre, Miguel de la Madrid and his wife Paloma Cordero, Liébano Sáenz, Epigmenio Ibarra and his wife Verónica Velasco, David Ibarra Muñoz, Héctor Aguilar Camín and his wife Ángles Mastretta, Monsiváis, Iván Restrepo, Payán Velver, Rolando Cordera, Emilio Azcárraga Jean, Jesús Silva Herzog, Santiago Creel, Rafael Tovar y de Teresa, Ricardo Rocha, Germán Dehesa, Gerardo Estrada, Luis Yáñez and Adriana Salinas, Antonio del Valle Ruiz, Lorenzo Zambrano, Juan Antonio Pérez Simon, Fernando Lerdo de Tejada and his wife Marinela Servijte, Tania Libertad, Fernando Solana, Porfirio Muñoz Ledo, Juan Soriano, Manuel Felguérez, María Felix and Cecilia Occelli.

When Slim acquired Teléfonos de México, the senator Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas Solórzano contested the operation with Porfirio Muñoz Ledo, another leftist politician and one of the founders of the PRD. The PRD even presented a complaint to the Attorney General’s Office on this very fact. Cardenas said that never in his life had he dealt with Slim and therefore could not speak of personal grudges. But his differences with the tycoon were diluted when the PRD politician Andrés Manuel López Obrador invited Slim and businessman Emilio Azcárraga Jean to participate in economic projects for the nation’s capital.

The Federal District’s plans consisted of the creation of industrial parks, the restoration of the Historic Center Alameda-Reformation and the Basilica Cathedral, the expansion of the transport network, and the promotion of emerging environmental markets through a multi-million dollar investment.

The Italian architect Francesco Bandarín, technical manager of the International Campaign for the Conservation of Vienna, said that the Historic Center of Mexico City (classified as a Cultural Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1987) suffers a severe degradation and requires “a global conservation policy.”

The recovery of the Historic Centre was initiated by Slim and Pepe Iturriaga. Andrés Manuel López Obrador was interested in the Reform Promenade and invited Slim to invest, but the employer insisted that for him, the priority was the Historic Center as long as President Vicente Fox would support the project. With or without López Obrador, Slim was determined to rescue the Historic Center, which finally happened. He was appointed coordinator of the Executive Committee in which the Cardinal Norberto Rivera, journalist and historian Jacobo Zabludovsky and historian Guillermo Tovar y de Teresa all participated, and with whom Slim had spoken of the urgent need to carry out this project long before getting involved. López Obrador ended up recognizing that Slim’s presence on the committee was important because it would guarantee the participation of other entrepreneurs in the hotel industry as well as others who wanted to invest in parking lots or in housing projects. They would immediately become active in the revitalization of the Historic Center, and only then would people return to populate the area that for years had become depopulated. For López Obrador, no one was more influential than the Telmex tycoon in promoting the regeneration of the area.

On April 4, 2002, the Diario Oficial published news of the granting of fiscal and administrative facilities for those willing to invest in the recovery of the Historic Center in zone “B,” as President Fox announced during a working trip to Mexico City where he accompanied the prime minister, Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

The resolution for zone “A” was conducted in October 2001. As for zone “B,” its limits were the streets of La Merced, Abraham González, Reforma, Zaragoza, Ferrocarril de Cintura, Herreros, Ánfora, Labradores and Doctor Liceaga, to name a few.

According to data provided by the trust to rescue the Historic Centre, zone “A” consisted of avenues such as Lázaro Cárdenas, Izazaga, Juárez, Hidalgo, and also the streets of Perú, Chile, Paraguay, among others.

The great challenge would be the construction aspect. Before December 31, 2002, the first town made up of thirty-one blocks comprised of the Eje Central (Central Axis) and Donceles to Venustiano Carranza. It was to be built by February 5, requiring the investment of MX$500 million that would be broken down as follows: MX$100 million in public safety, MX$25 million in rearrangement of mobile vendors and MX$375 million in public works.

The purpose of this project would be to reorder the economic and social activities of the Historic Centre, which is comprised of 668 blocks, as well as restore and reconstruct buildings in keeping with historical, architectural, monumental and urban importance of the area. The decree issued by the Federal Government established the following incentives for properties that are within zones “A” and “B” of the Center:

• Investments in real estate may be deducted immediately and up to one hundred percent.

• Investments in property repairs and adaptations involving additions or improvements to fixed assets shall enjoy the same benefit as they increase in productivity, life, or allow the property to be used differently than what had originally been provided.

• Paperwork is given for immovable property when it is disposed of for rehabilitation or restoration, with respect to the fact that the transferor may be treated as an acquisition cost for updates of at least forty percent of the amount of the transfer.

• Fiscal stimulus is given in asset tax for taxpayers required to pay on the real estate that is owned and is being rehabilitated or restored.

Slim, from the beginning of the project, contemplated that the recovery of the Historic Center would encourage new family life and economic and social development in an area where there are sixty museums and over three thousand cultural events each year. They found that the palaces, buildings, shopping areas and neighborhoods all had immense valueand should be used for work and fun and to enjoy the rich history, and to walk safely and sleep peacefully.

Many street vendors were removed and a new security strategy was implemented. More than a hundred fifty high-definition cameras were installed and such efforts began to bear fruit. Thanks to technology and surveys that were conducted every month, stronger security was achieved.

The restored old mansions became homes for than five hundred families who became the newest tenants in the Historic Center. Traditional restaurants that closed with the seizure re-opened and began encouraging others to open their doors. Some corporations that had their headquarters in Santa Fe installed part of their business in the Latin American Tower. In Juárez, in front of the Fine Arts Museum (which was once the headquarters of Financial Approvals, now Banca Serfin), a department store opened, the largest in the Federal District, accompanied by restaurants and other businesses. This complex attracts the attention of more than a million and a half visitors who cross the Central Axis and Madero daily. Banamex-Citigroup also reopened in the refurbished Palacio de Iturbide.

Slim bought the old Mexican Stock Exchange building on Calle de Uruguay 68 where he worked as a stockbroker and where he was once not allowed to enter because he didn’t bring a tie. There, he set up an entertainment center.

One of the first records on the recovery of the Historic Center was the initiative of historian José Iturriaga, who was worried about the deterioration of the area. He proposed a work program to then-President Adolfo López Mateos to restore buildings of Hispanic heritage and restrict street vendors. Iturriaga proposed to improve the Zócalo, the streets of Moneda, Santísima, Guatemala, Rodríguez, Puebla, San Ildefonso and Belisario Domínguez, along with the squares Loreto, Santo Domingo and La Concepción. The project included loops without traffic and created overpasses, as well as creating a company with capital of US$1.5 million. Although he mustered the interest of several bankers, the plan did not prosper because of political pressure from The n-head of the Federal District Ernesto P. Uruchurtu and his threat of resignation to destabilize the presidency of López Mateos. To calm political spirit, in 1964 he decided to appoint José Iturriaga ambassador to the USSR. Upon his return, Agustín Legorreta, proposed the creation of a company, México Antiguo, S.A., which would buy buildings for the restoration and recovery project of the Historic Center.

After contributing to the restoration of the Historic Center, Slim’s attention moved to another neglected area of Mexico City. In the municipality of Nezahualcóyotl, on area of 600,000 square meters (646,000 square feet), he transformed the former landfill Xochiaca into the Telmex Center for Bicentennial Sports. The project proved to be an ecological rescue and a successful fight against marginalization and poverty.

At its founding, Nezahualcóyotl had less than half a million people, most from the country’s poorest states (Michoacán, Guanajuato, Oaxaca, Puebla, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Veracruz, Tlaxcala, Guerrero, Aguascalientes, Morelos, Querétaro, Chiapas and Zacatecas, including the same settlers of the State of Mexico).

Anthropologists and sociologists referred to Nezahualcóyotl as the Calcutta, India, of Mexico. The city stands in stark contrast to the opulent neighborhoods of Mexico City like Polanco, San Ángel and Las Lomas. These districts were seen as a haven when the country lived the idyllic Mexican Miracle and members of Mexican high society traveled to American shopping centers and malls in search of fayuca25. In South America, the wealthy Mexicans were offered special packages, credit cards, bilingual shopkeepers, and special credit lines to support their industry of pleasure and consumption.

Though this period was called “stabilizing development,” it was marked by uneven progress in which a small, middleclass segment of the population, highly protected by government policies, grew richer. However, their increased spending was not enough to redeem or meet deficiencies of the marginalized people. This trend paved the way for the first steps of Mexican unionism. In short, it was the model of development for a few Mexicans, but the inhabitants of Neza were excluded. Since then, Neza was a collage of poverty, a ghetto in an area of 62.4 square kilometers (twenty-four square miles) with borders marked by social strata rather than physical or political boundaries. The unsavory trademarks of this poverty-stricken district included alcoholism, drug addiction, death by malnutrition, unemployment, and violence.

Until two decades ago, schools in Neza saw seventy-five percent of primary school children drop out before completing six years of compulsory education. The illiteracy rate exceeded twenty percent and functional illiteracy reached thirty percent.

Sociologists summarized it as the decade of the defeated. According to surveys published by the journal Unidad y Línea of the Popular Education Services (SEPAC), the ideology of men in Nezahualcóyotl disaggregated as follows:

• Fatalism: “There will always be poor: they are poor because they are lazy and drunkards.”

• Impotence: “I am unable to do anything.”

• Masochism: “I must suffer on this earth to gain heaven.”

• Individualism: “I have to improve myself in order to be better, with work and perseverance one becomes rich.”

• Skepticism: “Nothing can change anyway. At best I will lose what little I have.”

• Reformism: “We have to change things gradually, without violence, without haste.”

• Consumerism: “It is most important to get things.”

• The technocrat “One must have titles and deeds to have anything at all.”

• The machismo: “I am the master of my house.”

The municipality of Nezahualcóyotl, considered one of the poorest in the country, was named in honor of the king of Texcoco. Ironically, the poet and emperor of the Aztecs was distinguished by grandeur. For example, when they celebrated the centennial of the founding of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, they built a grand castle at the foot of the hill of Chapultepec. Texcoco (where Neza now sits, but once part of its jurisdiction) had several shining moments, even in the nineteenth century after the founding of the State of Mexico. Texcoco was appointed residence of the Supreme Powers of the State in January 4, 1827. However, over time it entered into a process of decay. In 1963, when a municipal decree formally entitled Nezahualcóyotl to its own government, its growth was marked by lawlessness.

The first generation of Necenses (people of Neza) emerged under the stigma of being born to lose. Many lived in half-built, cardboard or wooden shacks among endless rows of water tanks where the haze of dust storms mingled with the smoke of burning garbage. In an incipient city with long, monotonous streets and neglected green areas where few trees languish under the heat, anguish, bitterness and hatred festered. Adding to the failure of schools were the required “contributions.” Official primary schools charged twenty dollars on average for the registration of each child even though this practice violated the right to education ensured by the constitution. The collection of these contributions funded a wide array of supplies and services: glass, seats, paint, janitorial services, delivery receipts, certificates, tests and extra-curricular activities such as dance classes. However, teachers did not give official receipts for their fees.

So dismal was the picture of this emerging area that the company Televisa planned to install a cable system free of charge for economically disadvantaged urban areas. Televisa would provide Nezahualcóyotl with thirty simultaneous channels of transmission to provide “information and guidance for proper handling of a more immediate reality, individual, family and community development, and to provide roots and love for the area they inhabit.” However, Televisa fell short on their plans and left everything in the pipeline.

Nevertheless, Nezahualcóyotl has grown by leaps and bounds. Urbanization continues to progress as well as the development of infrastructure.

Slim undertook the ecological rescue of an extremely important zone, an area in which there were a thousand tons of garbage and which generated serious pollution. The waste was compacted and covered with several layers of soil, eliminating vermin, falling particles and airborne bacteria as well as reducing the pollution of groundwater from the putrefaction of organic waste.

What was once the Board of Xochiaca is now a shopping mall, two universities, a technological research center and a hospital zone, collectively known as the Bicentennial Garden City. The Telmex Bicentennial Sports Center is also self-sustaining. Its four ecologically sound lagoons gather up to five million liters (over one million gallons) of water per year and provide five thousand permanent jobs.

The sports facilities are quite extensive and offer free facilities for recreation with twenty-five soccer fields, four tennis courts, four basketball courts, four volleyball courts, two football fields, and two baseball fields. The complex contains a stadium with a capacity for over three thousand, a playground, tennis aerobics, cycling, squash, a gym, landscaping, parking and a helipad.

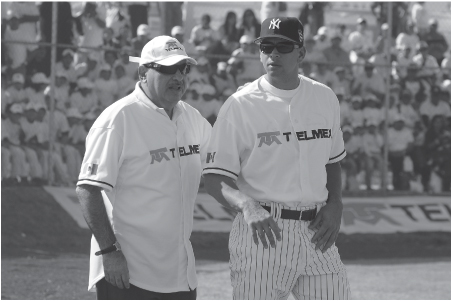

To inaugurate the sports facilities, Slim invited the star player Alex Rodriguez from the New York Yankees, named the best baseball player in the Major League in the 2007-2008 season.

One of Slim’s little-known interests is his fondness of sports. He is a friend of Edson Arantes do Nascimento (Pelé) and many baseball stars. Though baseball is his favorite sport, this does not stop his companies from supporting and advertising their professional soccer teams in the first division. Though on the board of the Condors, A.C., he has donated to American football teams. He enjoys playing American football himself.

However, baseball is Slim’s greatest passion. When the slugger Mark McGwire set a record for homeruns, the mogul wrote an article in Letras Libres, a magazine run by Slim’s friend and historian Enrique Krauze, where he displayed his knowledge by placing emphasis on the diamond statistics.

Baseball, whose Mexican supporters seem to have woken up after long periods of half-empty stands, is a spectacular sport that much depends on the abilities and technical skills of its practitioners—but also, the deployment of intelligence. Hence, the best games are those known as “pitching duels,” close games that are usually determined by good fielding or the solo homerun.

In baseball, like no other team sport, the numbers speak, memory is activated, and legends are forged. Unfortunately, it is impossible to reconstruct, in this sense, the statistics of the American Negro League (ANL) since the majors adhered absurdly to the “color barrier” (broken in 1947 by the second baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers, Jackie Robinson).

Those leagues—like those that Mexico could benefit from, importing outstanding figures in the time of businessman Jorge Pasquel—along with Cuba, boasted teams of legendary players. The memory brings to mind, and in no particular order, the names of Josh Gibson, Martin Dihigo, Roberto Ortiz, Ray Mamerto Dandrige, James Cool Papa Bell, Leon Day, Theolic Smith, Burnis Wright, Cristóbal Torriente, Silvio García, Ramón Bragaña, and Luis Olmo. What fan who knew of these star athletes could escape the seduction of their legend?

In the Dominican Republic, at the beginning of the Great American Depression, the dictator Trujillo took great players from the Negro Leagues, causing chaos in this country and instilling in the people a greater love and enrichment of a tradition whose fruits they enjoy today in the Major Leagues.

The numbers speak for themselves: think of the great exploits of pitchers like Nolan Ryan, who served for twenty-seven seasons. There was also the black pitcher Satchel Paige, who played in the big leagues for forty-two years. He won six games and lost only one in his first season, and Paige was almost a sexagenarian [by his final game]. Among the pitchers is a group that can be considered as the Big Five including Paige, Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson, Grover Alexander and Cy Young. After them, many characters have graced the mound, people of yesterday and of today, and their memory brings us happiness.

I quote in non-chronological order: Whitey Ford, Lefty Grove, Vic Raschi, Sandy Koufax, Sal Maglie, Warren Spahn, Nolan Ryan, Ed Walsh, Three Fingers Brown, Adie Joss, Steve Carlton, Gaylord Perry, Tom Seaver, Allie Reynolds, Bob Lemon, Bob Gibson, Bob Feller, Don Drysdale, Early Wynn, Sam McDowell, and the rescuers, some still active: John Franco, Dennis Eckersley, Randy Myers, Jeff Reardon, Rollie Fingers, Jeff Montgomery, Doug Jones, Rick Aguilera. These men come to the rescue when the ball is hot. Though they sit in on more than a thousand games, on average they play less than two tickets per occurrence, and are winners or losers in the game twenty-five percent of the time. The closers are pitchers with good control, very mild nerves, and good punchers. Among active starters, one can’t forget Roger Clemens (who has won the Cy Young Award five times for best pitcher) Greg Maddux to Dominican Pedro Martinez (a new important figure) Tom Glavine, Dave Cone and output, Orel Hershiser and Dwight Gooden.

On the pitch there are brands that seem insurmountable: the 7.355 entries drawn by Cy Young, the 511 victories achieved by this hero of the squadrons of Cleveland and Boston; the clean sweep by Ed Walsh (1.81); the percentage of wins and losses at Ford (690); the number of strikeouts by Ryan (5.714); the rate of strikeouts for Randy Johnson (once per nine innings); the number of wins for Jack Chesbro (41 obtained in 1904); the strikeouts per game Sandy Koufax achieved during his career as shortstop for the Dodgers (an average of 9.28, just below the 9.55 of Ryan and of course the 10.6 that keeps Randy Johnson on top, now playing with the Arizona Diamonds).

The numbers speak and myths flourish also among hitters. For me, the top five of the century have been Babe Ruth (who built Yankee Stadium while consolidating the magic of the sport), Ty Cobb, Roger Hornby, Ted Williams and Lou Gehrig, without forgetting Honus Wagner, Eddie Collins, Joe Jackson, Ed Delahanty, Tris Speaker, Billy Hamilton, Willie Keeler, Nap Lajoie, Al Simmons, Stan Musial, Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle, Jimmie Foxx, Mel Ott, Hank Greenberg, Ralph Kiner, Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays Frank Robinson, Harmon Killebrew, George Sisler, Harry Heilmann, Roberto Clemente, Rose Peel between assets and Tony Gwyn, Wade Boggs, Cal Ripken, Rickey Henderson, Ken Griffey Jr., Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, Barry Bonds, Larry Walker Frank Thomas, Albert Belle, Juan Gonzalez, Jose Canseco…

The numbers speak for themselves: Babe Ruth’s 714 homeruns were hit within fewer times at bat than those of Hank Aaron (755). The frequency of his big hits has never been surpassed.

McGwire, meanwhile, has five seasons with fifty or more homeruns. Only ten batsmen have ever overcome that barrier: Ruth (60 in 1927), Roger Maris (61 in 1961), Foxx (58 in 1932), Greenberg (58 in 1938), Mantle (54 in 1961), Wilson (56, 1930), Kiner (54 in 1949), Mays (52 in 1965), George Foster (52 in 1977) and Mize (51 in 1947). Among the assets they have McGwire (which reached 70 in 1998), Sosa (66 in 1998), Griffey Jr. (56 in 1997 and 1998), Cecil Fielder (51 in 1990), Greg Vaughn (50 in 1998), Albert Belle (50, 1995).

Playing with astonishing numbers, McGwire would have exceeded eight homers had he played twenty-two seasons. Griffey, with fewer shifts, exceed the rate set by Aaron. In 2001, McGwire will be the fourth-best homerun hitter in history behind only Aaron, Ruth and Mays. He will most likely be close behind Bonds, Canseco and Griffey Jr., though he will exceed five hundred homeruns. In 1927, Ruth hit a homerun on average every nine times at bat. In 1998, McGwire did it every 7.27 times.

The numbers speak in an infinite diamond: the memory, imagination, and the creation of legends. The renewed enthusiasm for baseball once again plays with intelligence.

Slim’s addiction to baseball is so great that he has a consortium with Ogden de México. With sixty-six percent US capital and the remaining thirty-four percent Mexican, he is one of the main operators in the management of stadiums and arenas in the United States. He managed the sports facilities where the Sacramento Kings and the Chicago Bulls played as well as other centers in Chicago, Baltimore and Philadelphia. Slim was presented with a project to build a professional baseball stadium on the land that he occupied for many years with his cousin Alfredo Harp Helú of Banamex, Red Devils team owner. However, Slim denied the rumors that a major league franchise would play in Mexico stating that he does not want to make his hobby into a business; he just likes to enjoy baseball.

Carlos Slim with New York Yankee Alex Rodriguez.