Of all the Elizabethan Sea Dogs, Drake was the perfect choice as commander of this great expedition. He was resourceful, aggressive, and he knew the Caribbean like no other Englishman of his generation. Better still, he had a deep-rooted dislike of the Spanish, a legacy of his experience at their hands at San Juan de Ulúa 17 years before. He could be relied upon to inflict as much damage on Spain’s overseas empire as he could. Besides, as this was a royally sanctioned quest for treasure, Drake’s avarice meant that he would make a thorough job of plundering the riches of the Spanish Main, on behalf of his Queen and his other backers. It can even be said that Drake’s experiences had groomed him for this command – the expedition would be the culmination of almost two decades of seafaring, privateering and warfare.

Francis Drake was born in Tavistock, a small market town on the western edge of Dartmoor, some 15 miles north of Plymouth. He was the eldest son of Edmund and Mary Drake, a young farming couple whose lands at Crowndale on the banks of the River Tavy were rented from the local landowner Lord Russell, the Earl of Bedford. Actually, Edmund’s elder brother John ran the farm; his younger brother merely assisted him. Clearly the Drakes had good social connections – Francis was named after his godfather Francis Russell, the teenage son of the local landowner.

The exact year of Francis’ birth is unclear, but it probably took place around 1539 or 1540. He was the eldest of 12 brothers, but what could have been an idyllic rural childhood was cut short in 1549 when Francis and the family fled the country. Edmund Drake was a staunch Protestant, and was caught up in the local religious unrest dubbed the ‘Prayerbook Rebellion’. The family escaped to Kent, where they established a new home in a houseboat (or hulk), moored in the River Medway. Edmund re-invented himself as a Protestant clergyman, preaching to local seafarers.

In his early teens Francis went to sea as a crewman of a trading vessel, plying between Kent and nearby European ports. He probably served as an apprentice to the owner, as it appears he inherited the vessel and the business when his mentor died. This meant that by the time he was 20 Drake was already an experienced seaman, and his own master.

Still, it seems the young man preferred blue water sailing to coastal trade, as he sold his vessel in Plymouth, and drew on his family connections to join the employ of his second cousin John Hawkins. By that time Hawkins had already made one successful trading voyage to the Caribbean, selling slaves he picked up on the West African coast to colonists in the Spanish New World. In 1564–65 Hawkins repeated the voyage, but the indications are that Drake didn’t accompany him. Instead he acted as Hawkins’ representative on a trading voyage to Spain and back. His big chance would come on Hawkins’ third Caribbean voyage. The only problem was that what Hawkins was doing was illegal, or more accurately it was illegal in the eyes of the Spanish.

John Hawkins (1532–95) was a kinsman of Drake, and one of the leading shipowners in Plymouth. Drake accompanied Hawkins on his trading voyage to the Spanish Main in 1567–69, and both men escaped the debacle at San Juan de Ulúa.

The Spaniards had a proprietary attitude to the New World in general and the Caribbean in particular. While other Europeans had occasionally ventured into these waters – the first English ‘interloper’ did so in 1527 – the region was generally seen as off-limits. In the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), drawn up in the wake of Columbus’ first voyage, Spain was granted control of all lands to the west of a line of longitude 38˚ West, which bisected the Atlantic Ocean, leaving Brazil to the Portuguese and the rest of the Americas to the Spanish.

Until 1558 English ventures ‘beyond the line’ were discouraged, for fear of sparking a diplomatic incident. The accession of Queen Elizabeth I that year marked a change of policy, and the Spanish Main was no longer barred to English adventurers.

John Hawkins was quick to take advantage of this development. However, he sailed across the line with peaceful intentions, coming to trade rather than to plunder. In 1562 he sailed from Plymouth in three small ships, and on the West African coast he visited local chieftains, where he exchanged trade goods for slaves. He then transported 300 of these unfortunates across the Atlantic, and arrived in the West Indies early the following year. Hawkins headed to Hispaniola, but he avoided the main settlement of Santo Domingo, and instead he anchored further down the coast, where he sold his slaves to local plantation owners. He returned to England a wealthy man.

Hawkins’ second voyage in 1564 was a much larger affair, as he had secured several important backers. These included Queen Elizabeth herself, who leased Hawkins the ageing royal warship Jesus of Lubeck as part of her stake. Once again Hawkins collected a cargo of slaves on the West African coast, but this time when he reached the West Indies he sailed southwards towards the Tierra Firme – the Caribbean coast of South America. The Spanish settlers of Margarita were unwilling to do business with him, for fear of reprisal from the Spanish authorities. Hawkins finally managed to sell his slaves in Rio de la Hatcha further up the coast, but only after he threatened to turn his guns on the town. This threat, though, was almost certainly a pre-arranged gesture, arranged between Hawkins and the town mayor as a means of saving face, and to avoid official retribution. In late 1565, Hawkins returned to Plymouth, his voyage having proved even more lucrative than the last. Drake must have envied his kinsman, and he was determined not to miss out on any new opportunity.

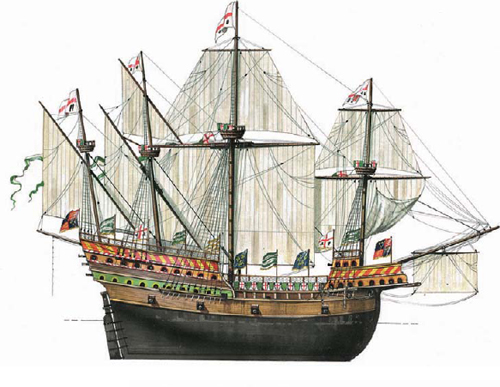

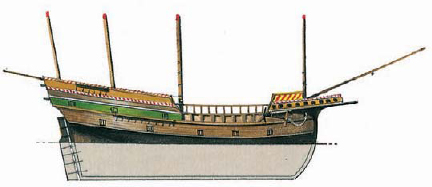

When Queen Elizabeth leased John Hawkins the ageing warship Jesus of Lubeck in 1564, the Plymouth adventurer set about modernizing her, lowering her superstructure and making her more seaworthy. Her new appearance is shown below – this was how she looked when she was captured by the Spanish at San Juan de Ulúa in 1568. Painting by Tony Bryan. (Originally in Osprey New Vanguard 149: Tudor Warships (2).)

First, however, Drake would sail under a different commander. The political repercussions of Hawkins’ last foray into the Spanish Main kept Hawkins himself in England, so when a new expedition left Plymouth on 9 November 1566, the three small ships were led by John Lovell, a captain in Hawkins’ employ. This time Drake went with them, venturing further from England than he ever had before. Off the Cape Verde Islands Lovell attacked and captured several Portuguese ships, which gave Drake his first experience of naval combat. This action was nothing other than piracy, but Lovell realized that the niceties of European law and diplomacy counted for little in African or American waters. The likelihood is that these attacks gave Lovell all the slaves he needed, saving him the need to spend several unhealthy weeks on the African coast.

After a fast transatlantic voyage, Lovell arrived off the small settlement of Borburata, on the coast of Tierra Firme (now Venezuela), where he encountered a similar squadron of French interlopers. Lovell moved along the coast to Rio de la Hatcha, where the local administrator refused to deal with him. Lovell lingered for a week, hoping for a change of heart that never came. He then sailed off, pausing only to deposit the least healthy of his slaves on the beach. He may well have sold the rest of his human cargo on Hispaniola, but by September 1567 Lovell and Drake were back in Plymouth.

There Drake discovered that Hawkins was making his final preparations for another trading voyage, and volunteered his services. This time Drake would be part of it, serving Hawkins as one of his junior officers. Hawkins’ squadron consisted of five ships, two of which were leased to him by the Queen. The venerable royal warship Jesus of Lubeck of 700 tons had been modified extensively, but she was still old, slow and barely seaworthy. The smaller 300-ton royal warship Minion was better suited to the voyage, but regardless Hawkins needed the Queen’s backing, and was in no position to reject her stake in the venture. The rest of his force consisted of the smaller ships William and John and Swallow, accompanied by the smaller Judith (a 50-ton bark). Finally these five ships were accompanied by the pinnace Angel, a tiny vessel of just 35 tons.

The expedition sailed from Plymouth on 2 October 1567, with Hawkins flying his flag from the Jesus of Lubeck. The voyage seemed doomed from the start. A storm forced Hawkins to take shelter in Tenerife, and the Spanish governor duly wrote to Madrid, warning them that Hawkins was undoubtedly bound for the Spanish Main. When Hawkins eventually arrived off the West African coast he found that the coastal tribes were unwilling to trade with him. He resorted to Lowell’s method of overpowering Portuguese slave ships, and taking their human cargo. Drake was rewarded with the command of one of these captured vessels – the Gratia Dei. Actually, it had only just been captured from the Portuguese by the French, but Hawkins and Drake cared little about rightful ownership.

An English seaman of the late 16th century, a detail from the frontispiece of The Mariners Mirrour by the Dutch pilot Lucas Jansz Waghenaer, and engraved by Theodore de Bry. His dress is typical of the well-dressed maritime officer of this period.

Queen Elizabeth I (1533– 1603, reigned from 1558) used Drake as a strategic weapon, in an attempt to encourage King Philip II of Spain to negotiate with her, rather than to embark on a costly war with England.

The expedition was still short of slaves, so Hawkins decided to involve himself in African politics. A coastal tribe was at war with an inland one, so the Englishman offered his services in return for a share of the prisoners. In January Hawkins led an attack on a fortified village on the River Tagarin, in what is now Liberia. English firepower proved decisive, and Hawkins duly secured another 250 slaves. The expedition then set sail for the Americas, making landfall off Dominica in late March 1568. His first port of call was the Isla Margarita off the Tierra Firme coast, but the governor refused to trade with him. He encountered the same response at Borburata, Curaçao and Rio de la Hatcha. In fact, at the last port the Spanish even fired on Hawkins’ ships, driving Hawkins back out to sea.

He eventually appeared off Santa Marta, where the residents proved a little more forthcoming. He went through the same ritual he performed off Rio de la Hatcha three years before, pretending to fire on the tiny settlement to induce its surrender. This display then gave the governor no option but to trade with the interlopers. Hawkins managed to sell 110 slaves there, and set off westwards in search of another marketplace. The gun batteries of Cartagena opened fire when he approached, but the English lingered just out of range for several days before heading away to the north. Drake undoubtedly used this time to study the defences of the port. Hawkins’ force now consisted of eight vessels – his original flotilla, the Gratia Dei and another Portuguese prize.

By mid August they were passing through the Yucatan Channel, the start of a voyage around Cuba and out into the Atlantic. However, they were overtaken by a violent storm – probably a hurricane – and the fleet was blown deep into the Gulf of Mexico. The William and John became separated from the rest, and returned to Plymouth. The remainder of the squadron stayed together, but the ageing Jesus of Lubeck almost foundered, as ‘on both sides of her stern the planks did open and shut with every sea’. If his flagship was going to make it back home Hawkins needed to put into a port to repair her. He settled on Vera Cruz on the coast of Mexico, an important treasure port and a thriving town.

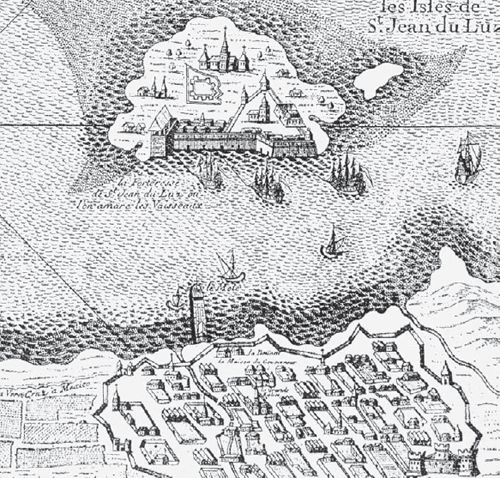

The town was defended by an island fort – San Juan de Ulúa – which Hawkins captured by bluff, by pretending his squadron was a Spanish one in need of repair. He then moored his ships under the guns of the fortress, and his men set to repairing their ships. Hawkins was in a hurry. Local officials told him that the annual treasure flota (fleet) was due to arrive at the end of the month, and he wanted to be far offshore when it appeared. Unfortunately for him, on 14 September – just two days later – the flota arrived, and Hawkins was trapped. The Spanish naval commander Admiral Luján, realized that a straightforward battle would be costly, so he and Hawkins arranged a truce. While his intentions were probably pure, his passenger Don Martinez Enriques, the new Viceroy of Mexico, had no intention of dealing with interlopers. While both sides watched each other warily, the Viceroy ordered the admiral to prepare a surprise attack.

The port of Vera Cruz in Mexico was an important Spanish treasure port during this period, and consequently the island of San Juan de Ulúa, which lay just off the harbour, was heavily fortified. It was here that Hawkins and Drake were driven by a hurricane in 1568.

At dawn on 23 September the Spanish launched their assault, overwhelming the small English garrison guarding the fortress. They then turned the guns on the English ships moored in front of them, while the Spanish galleons joined in the bombardment. The Jesus of Lubeck attracted most of the fire, and within an hour she was battered, dismasted and holed. Hawkins had little choice but to abandon her, and concentrated on saving his remaining ships and their crews. As the Minion manoeuvred to pick up the flagship’s crew, a Spanish fireship appeared, prompting Captain Hampton of the Minion to veer away as the last of the Jesus’ crew were clambering to safety. Hawkins jumped for it, but others weren’t so lucky, and were left behind to be captured by the Spaniards. In fact, only two English ships made it to safety – the battered Minion and the smaller Judith, which was now commanded by Francis Drake.

The two ships became separated in the dark, and by dawn the Minion was alone. Drake was already over the horizon, leaving his kinsman to fend for himself. Hawkins clearly thought Drake had deserted him, and when the Minion finally limped home in late January 1569 he said as much. Drake himself arrived in Plymouth less than a week earlier, and of more than 300 men of both ships who escaped the debacle at San Juan de Ulúa, only 25 survived long enough to see England again. Others who insisted on being put ashore rather than face starvation at sea were butchered by local Indians. Few of those left behind in Vera Cruz ever returned home either. Instead they ended their days as galley slaves, or were burned as heretics.

Neither Drake nor Hawkins ever forgave the Spaniards for their treachery. Hawkins wrote to the Queen seeking redress, as according to English law he could be issued with a ‘letter of reprisal’, which allowed him to confiscate Spanish goods to help recoup his losses. The fact that he was in Spanish waters illegally was never mentioned. However, it was Drake rather than Hawkins who would return to the Caribbean to seek revenge. Before San Juan de Ulúa, Drake had a strong dislike of the Spanish because their religious beliefs were at odds with his. What he viewed as the treachery of the Spanish Viceroy turned this dislike into a consuming hatred, and the desire to avenge his lost shipmates. Drake would soon prove that the Spanish had tangled with the wrong man.