First though, Drake had to attend to some private business. For a year or more he had been courting a lady called Mary Newman, and on 4 July 1569 they were married in a church in Plymouth. We know very little about Drake’s activities over the months that followed, so presumably he was making the most of his new-found domestic bliss in Plymouth. He also spent the time arranging a voyage of reprisal against the Spanish. Drake lacked Hawkins’ money and connections, but although he was a relatively young and unknown commander, he managed to gather together a small force. Still, it was barely large enough to count as a fully fledged squadron, let alone one capable of causing trouble in American waters. Therefore Drake’s expedition of 1569–70 could be little more than a reconnaissance in force.

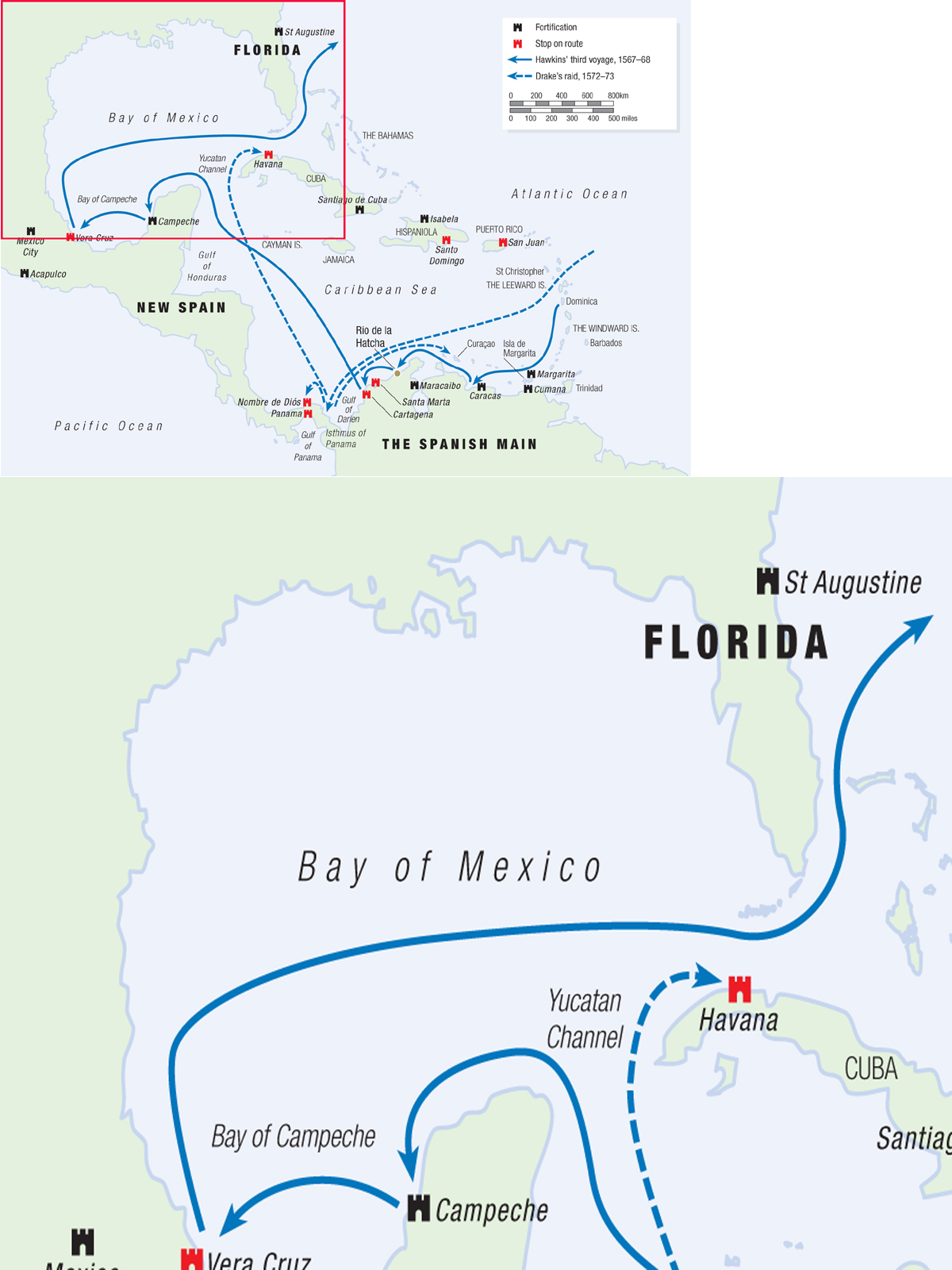

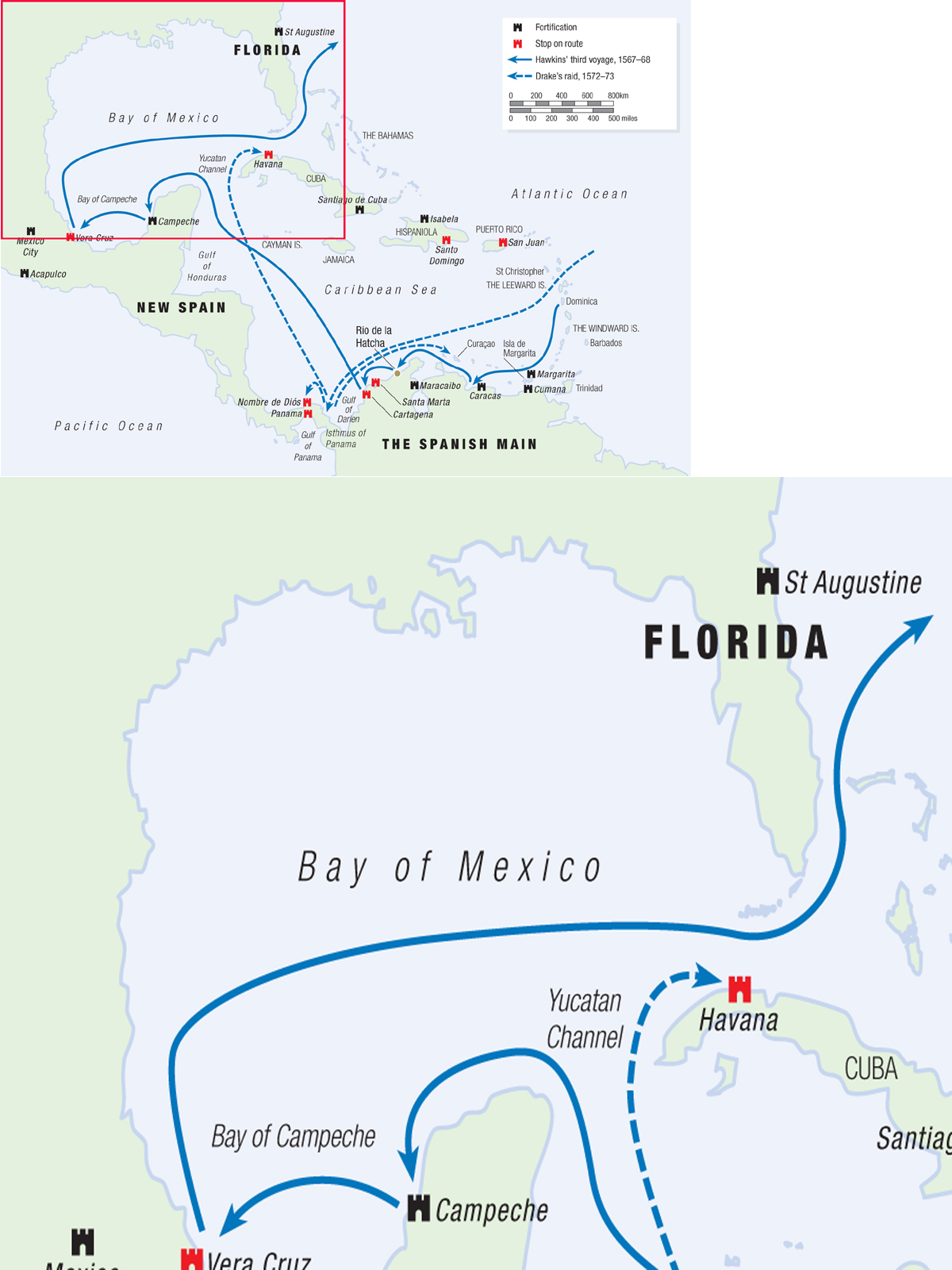

Early English raids in the Caribbean.

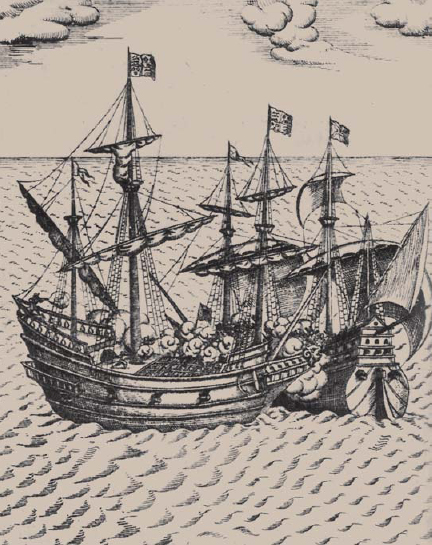

The English ships used by Drake and his contemporaries ranged from large royal warships to tiny pinnaces. Although slightly fanciful, this depiction of the 450-ton Golden Lion gives us a fair impression of what the larger of these vessels looked like.

His own flagship was the Dragon, a tiny 35-ton vessel, little bigger than a large modern sailing yacht. It was accompanied by the 25-ton vessel Swan of Plymouth, a vessel Drake bought from the proceeds of his earlier voyage with Lovell. The total crew of both ships couldn’t have been more than 50 men. Like most privateers they weren’t paid – instead they expected a share of any plunder, so like their commander they were eager for Spanish treasure. The small expedition set sail in November 1569, and presumably Drake made landfall in the West Indies early the following year. Unfortunately we know little about his activities on this first independent voyage. The Spanish reported several interlopers were operating in the Caribbean that year, most of whom were French. One of them was Drake.

Drake returned to Plymouth in the early summer of 1570. Queen Elizabeth subsequently granted Drake his letter of reprisal, giving him the legal right to attack Spanish ships and settlements. She presented one to Hawkins as well, but he was also given a royal appointment as a naval administrator, in charge of the Royal Dockyard at Deptford on the River Thames. His new job would keep him busy for several years, which meant he was unable to take advantage of his licence to wage a private war. This meant that of the two captains, it was Drake who would return to the Spanish Main, eager for revenge.

Drake immediately began organizing a new and larger expedition. This activity in itself suggests that his previous reconnaissance proved fruitful; without even a little plunder he would have been hard-pressed to raise another volunteer crew. This time the expedition would be even smaller, as Drake only used one ship – the little Swan. He probably sailed in November or December, as by mid February 1571 Drake appeared off the Isthmus of Panama. On 21 February he encountered a small Spanish warship near the mouth of the River Chagres. Drake and his men took it by surprise, boarding it before the Spanish had a chance to defend themselves. This would be the first of several prizes. As the Spanish described it: ‘upon the coast of Nombre de Dios [Drake] did rob diverse barques in the river of Chagres, and in the same river did rob diverse barques that were transporting of merchandise.’ Drake might only have had one small ship, but he knew how to cause trouble.

By that time he also had allies. French pirates (or ‘corsairs’ as they preferred to be called) were operating in the same area, and Drake fell in with a French Huguenot (French Protestant) captain, possibly the Jean Bontemps who was killed later that year during a botched attack on the Spanish island of Curaçao. The two interlopers must have operated together, as Drake’s small crew would have found it difficult to plunder so many ships without help. The Spanish themselves put the value of the plunder at 40,000 ducats, a sizeable fortune comprised of gold, silver and – according to the Spanish – ‘silks and taffeta’. Drake returned to Plymouth a rich man.

Drake began planning his next venture almost as soon as he returned. Once again he used his brother John Drake’s diminutive Swan of Plymouth, but this time he was flew his flag in the larger Pasco (or Pasha) of 70 tons, a vessel which was almost certainly supplied by John Hawkins, who was one of Drake’s financial backers. They two ships carried 73 men and boys between them. The expedition sailed in March 1572, and by July Drake was back in his old hunting ground of the Isthmus of Panama. This time, though, he had a very specific objective. He planned to attack Nombre de Dios, reportedly the treasure house of the New World.

During the later 16th century, the bulk of Spanish wealth from the New World came from the silver mines of Peru, the largest of which – Potosi – produced more silver each year than all the other mines put together in Europe or the Americas. Every year a fifth of the silver produced in these mines was earmarked for the Spanish treasury, and it was shipped northwards up the Pacific coast to Panama. From there it was transported across the Isthmus to Nombre de Dios, where it was stored, ready for collection by the annual Spanish treasure flota. Drake hoped to capture this huge cargo of silver before the Spanish ships arrived.

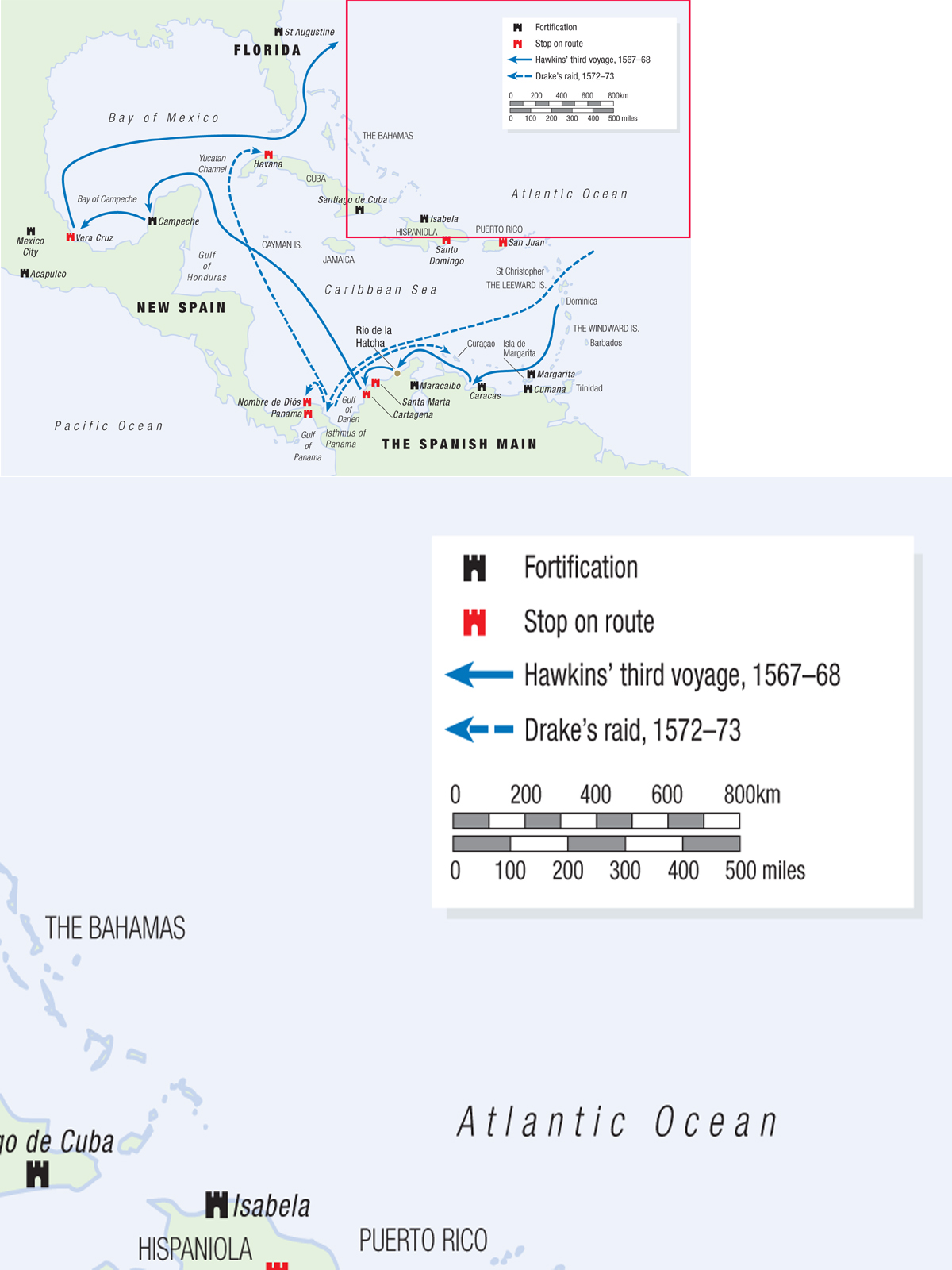

The treasure port of Nombre de Dios on the Caribbean coast of the Isthmus of Panama, as depicted in a crude Spanish chart of the harbour, drawn in 1541. Drake unsuccessfully attacked the small port in the summer of 1572.

First, however, he needed a base. He soon found what he was looking for – a half-hidden inlet about 130 miles south-east of Nombre de Dios, which he called Port Pheasant. Although its exact location was never revealed, it was probably the inlet near Darien, which was later called Puerto Escoces, as it became the site of a doomed Scottish colony in the last two years of the 17th century. Drake used his time in the anchorage to take on water and stores, to organize his men for the raid and to plan the attack. It was in Port Pheasant that Drake was joined by a small English ship, commanded by another interloper, Captain James Raunce. Raunce was the former master of the William and John, which took part in Hawkins’ last voyage but which avoided the debacle at San Juan de Ulúa. His vessel added another 50 men to Drake’s force.

Drake then sailed up the coast, and on the afternoon of 28 July he dropped anchor a few miles below the treasure port. Captain Raunce was left behind to guard the three ships, while Drake embarked 73 of his men in four small specially built pinnaces, and sailed them to within a mile or so of the town. He planned to launch a night attack on an unsuspecting port, and with the advantage of surprise on his side he had every chance of success. However, a Spanish vessel anchored close to the port spotted the English pinnaces, and a boat was launched to raise the alarm. Fortunately for Drake, one of his pinnaces blocked its path, and the Spanish longboat veered away. In fact, Drake’s dawn attack achieved complete surprise. The assault carried the English raiders into the centre of the town. Their big advantage was that the enemy had no idea just how few attackers there were. That was when it all started to go wrong.

Drake had some difficulty keeping his men together as they ran through the buildings in search of plunder. They encountered the town’s alcalde (mayor) in the main square, where the town militia were gathering. A short firefight ensued, but Drake’s men had the better of the exchange, and the defenders soon broke and ran. The English now controlled the town. At that moment a tropical downpour broke, soaking Drake’s men and wetting their powder and bowstrings. They took shelter as best they could, but the storm lasted more than half an hour, which gave the defenders a chance to rally. This time the Spanish realized they had numbers on their side.

Unknown to his men, Drake had been wounded in the fight, and he was losing blood. When the storm passed, he led his men to the main royal treasure warehouse, and ordered his brother John Drake to break down the door. It was then that Drake passed out through loss of blood, leaving his men virtually leaderless. John bound his leg, and the English commander was carried back to the boats, followed by the rest of his men. The treasure house remained untouched as the attackers concentrated on saving their leader. The opportunity had gone, the Spanish re-occupied the town centre and there was nothing for the attackers to do but row away to safety.

Although this coloured engraving depicts a French Huguenot raid on a Spanish port in the Caribbean, rather than one led by Drake, the scene shows how these raids were carried out – an amphibious landing, a quick assault, then the looting and destruction of the town.

Drake’s first major attack on the Spanish Main was a complete failure. Actually, Drake might have been luckier than he imagined. The Spanish treasure fleet had already cleared out the contents of the warehouse a few weeks earlier, and discovering it to be empty would have seriously weakened his credibility with his men. James Raunce decided to cut his losses and sail for home, leaving while Drake was still convalescing. Drake, though, was made of sterner stuff. He decided his men needed a quick success to boost their flagging morale, so he decided to sail south to Cartagena, his two small ships towing three pinnaces behind them.

The inner port was too well protected to assault, but Drake managed to slip into the outer roads undetected, and fell upon the nearest Spanish ship. It held nothing of value, nor did another larger 250-ton vessel. It turned out that the Spanish had warning of Drake’s approach, and all the valuable ships that could do so sought refuge behind the protective guns covering the inner harbour. Drake had been thwarted again, although the Spanish were also unable to prevent him from pillaging the two ships within sight of the town. He withdrew to the Islas San Bernardo, just off the coast. He really didn’t have enough crew to man all his ships, so he scuttled and burned the Swan, which left him with just the Pasco, the three pinnaces and about 60 men. It was hardly a major force, but Drake was determined to make his mark. He returned to Cartagena, but once again he found nothing of much value to plunder. He continued eastwards as far as Curaçao, but despite capturing a few prizes he never found a target of any real worth.

Meanwhile, Drake left his brother John in the islands with the third pinnace, with orders to gather supplies by trading with the local Indians, and to establish contact with the Cimaroons (runaway slaves) who inhabited the Darien coast. At Nombre de Dios the English had been joined by one of them, a former slave known as Diego. Drake soon realized that these desperate men hated the Spanish as much as he did. That made them potentially useful allies. Drake’s plan was to use this local contact to help him ambush the Spanish silver shipment before it reached Nombre de Dios, during its transit across the Isthmus of Panama. Unfortunately, John Drake was killed while attacking a passing Spanish ship, so when his brother Francis returned he not only had to deal with a double personal tragedy – a younger brother also succumbed to disease – but he discovered from the Cimaroons that his new plan had a flaw.

It was now December 1572. The next shipment was scheduled to take place in just a few weeks, and Drake had very little time to move his force to the Isthmus, put his men into place and set up an ambush before the Spanish treasure reached the safety of Nombre de Dios. It was a race against time. It took two weeks of marching before Drake and his small force reached their ambush site, a few miles from the village of Vente Cruces, and some 18 miles from Panama.

By mid February 1573, Drake had won his race. He had just 18 sailors with him, accompanied by around 20 Cimaroon allies. The Spanish would be using the Camino Real (Royal Road) that crossed the Isthmus from Panama to Nombre de Dios, and Drake hoped that by ambushing them close to the start they would be more likely to be off-guard. He split his men into two groups – one on each side of the road – and took the precaution of making them wear their shirts over their clothing, to help distinguish friend from foe.

Cimaroon lookouts alerted Drake when the Spanish approached, and soon the waiting Englishmen could hear the bells worn by the silver-carrying pack mules. Then, just moments before the silver train appear, a lone Spanish horseman rode into view, riding in the opposite direction (from Nombre de Dios). At that moment one of the English seamen, Robert Pike, rose from the bushes, wearing his discoloured white shirt. He had been drinking, and whether he chose the wrong moment to relieve himself or he was simply too befuddled to know what he was doing is unclear. In any event he was spotted, and the rider galloped off down the road to warn the approaching silver train. The treasure convoy was immediately turned around, and was protected by its strong escort as it withdrew back down the road towards Panama. Drake had little option but to make his escape, no doubt cursing Robert Pike as he went. Weeks of effort had been wasted by one drunken seaman.

In this late 16th-century chart showing the Isthmus of Panama, north is at the bottom, and the town of Porto Bello on the Mar del Norte lies on the Caribbean coast, a few miles west of Nombre de Dios.

The raiders passed through the village of Vente Cruces as they withdrew, driving out a small Spanish garrison before looting the place of provisions and a meagre haul of valuables. Drake then withdrew back to the coast and his ships, well aware that the countryside would soon be swarming with Spanish troops. They reached safety on 23 February, and Drake immediately began planning a second attempt. This time, though, he had more men at his command. On 23 March he was joined by a French Huguenot interloper called Guillaume Le Testu, and they decided to make a joint attempt at intercepting the silver shipment, which was due to leave Panama in a few weeks. One suspects that this time Robert Pike was left on board the ships.

During the last week of March, a force of 20 Frenchmen, 15 Englishmen and 20 Cimaroons landed on the coast a few miles from Nombre de Dios, and this time Drake set up his ambush on the outskirts of the port, so close that his scouts could hear the sound of carpenters repairing the waiting treasure galleons. This time there was no blunder. On 31 March the Spanish silver train appeared, and the plan worked perfectly. After a brief fight the 45-man escort were driven off, but a Cimaroon was killed in the exchange and Le Testu mortally wounded. While Drake and his men set about looting what they could from the pack mules, Le Testu’s men made arrangements to carry their dying commander to safety. In the end the plunder – reputedly valued at 200,000 ‘pieces-of-eight’ (pesos) – was too much to carry, and the Spanish in Nombre de Dios were expected to appear any minute. Drake took what little he could and buried the rest, hoping to come back for it later. With the Spanish now in full pursuit, the gravely wounded Le Testu had to be left behind too, and he was executed by the vengeful Spaniards.

The Spanish used the local population to extract silver for them from the mines in Mexico and Peru, as shown in this engraving by Theodore de Bry. The Spanish crown came to rely on this treasure to fund its wars in Europe.

Three days later Drake reached the site where he expected his pinnaces to be waiting for him. They weren’t there – a storm had delayed them. Ever resourceful, Drake built a raft, and it carried them down the Francisco River to safety, where the raiders finally came upon the pinnaces, working their way upriver to meet him. It would have been a joyful reunion if he had more plunder to show for his efforts. However, Drake had managed to seize enough gold to turn what had been a disastrous voyage into a marginally profitable one, even after splitting the plunder with the Huguenots. Drake hoped to return to pick up the buried silver, but a French straggler had been captured by the Spanish, then tortured until he revealed where the treasure had been buried. When Drake learned of this fresh disaster he decided to return home, and on 9 August the Pasco sailed into Plymouth, with just enough in its holds to warrant the 15-month-long raid.

The English share of the haul has been estimated at around 50,000 pesos, and even after dividing it amongst the crew and paying off investors, Drake still had a enough profit to clear his debts and to set himself up as a gentleman of modest standing. He also found himself something of a national celebrity. For the next two years Drake was busy elsewhere, campaigning in Ireland on behalf of the Queen, establishing a home with his new wife, and being presented at court. However, he also used this time to plan a new expedition, one even more ambitious than the last.

Although Drake spent two years doing other things, he also met influential courtiers, scientists and explorers, gathering what information he could about the South Sea, the region we now know as the Pacific Ocean. A plan evolved, whereby Drake would lead a small expedition into these largely uncharted waters and prey on Spanish shipping. At the same time he would gather whatever scientific and geographical information he could. In effect it would be a voyage of discovery, financed by plunder.

During the later 16th century, the Spanish regarded the Pacific as their own private ocean, and Spanish ships there were less well armed than those in the Caribbean. Spanish vessels transported silver northwards from Peru to Panama, and gold, spices and jewels from the Orient to Mexico. This last route, plied by the Manila galleons, was what interested Drake the most. They represented the ultimate piratical prize, a source of fabulous wealth for anyone bold enough to venture halfway round the world to fight for the treasure.

Queen Elizabeth shared Drake’s enthusiasm for the venture, and as plans took shape she became a secret shareholder in the expedition. For diplomatic reasons the English monarch was unable to be linked officially with the enterprise, but her sanction of it was widely known, and Drake’s financial backers included her leading advisors: the Earl of Leicester, Sir Francis Walsingham, Christopher Hatton and Sir William Wynter. In effect, the voyage would be an unofficial state-sponsored pirate cruise. Drake was even sent detailed instructions, ordering him to pass through the Strait of Magellan, explore the Pacific coast of America and make contact with locals willing to trade with English merchants.

Drake sailed from Plymouth in November 1577, but was forced back into port by a storm. He set sail again on 13 December, flying his flag in the 120-ton Pelican. She was accompanied by four other ships: the 80-ton Elizabeth commanded by John Wynter, the 30-ton Marigold commanded by John Thomas, the 15-ton pinnace Benedict and the 50-ton supply ship Swan.

From the start, the voyage was marked by dissension. Off the coast of Morocco the Benedict was abandoned for a Portuguese prize called the Christopher. Another captured Portuguese trading ship was renamed the Mary, in honour of Drake’s wife. He appointed Thomas Doughty to command her, but Drake soon suspected this new captain of plotting against him. He exchanged ships, placing Doughty in charge of the Pelican, presumably so that his activities could be watched more closely.

According to Drake, Doughty continued his seditious talk during the Atlantic crossing, and matters reached a head when the ships made landfall off the River Plate in mid March 1578. Drake transferred Doughty to the Swan, placing him under open arrest. From there the expedition sailed down the coast of South America, reaching Port St Julian near the entrance of the Magellan Strait on 18 June. It was there that Drake charged Doughty with inciting mutiny, and – bizarrely – of witchcraft. A trial was held, and as a result the unfortunate Doughty was sentenced to death, and then executed. The likelihood is that while Doughty was indeed a troublemaker, Drake decided he couldn’t afford any questioning of his authority during the voyage that lay ahead. His draconian act quelled any further dissent. While in Port St Julian Drake abandoned the Swan after distributing its stores, burned the Portuguese prizes and re-named the Pelican the Golden Hind. All was ready for the next dangerous phase of the expedition – the voyage into the storm-tossed seas of the Magellan Strait.

On 20 August the Golden Hind, Elizabeth and Marigold put to sea, and a week later they entered the treacherous waters of the Strait, which lay between the island of Tierra del Fuego and the South American mainland. This dangerous transit took the best part of two weeks. All seemed to be going well until they neared the Pacific Ocean. Then they were hit by a violent storm, a tempest more severe than anything any of these veteran English seamen had ever experienced. The Marigold foundered with all hands, while John Wynter in the Elizabeth and Francis Drake in the Golden Hind were separated by the storm, and the two captains would never see each other again until Drake’s return to Plymouth two years later. After waiting for Drake off the Peruvian coast, Wynter decided to complete the voyage on his own. He thought about heading westward across the Pacific to the East Indies, a region Drake had expressed an interest in exploring. Instead he decided to return home the way he had come, and he arrived back in Plymouth in June 1579.

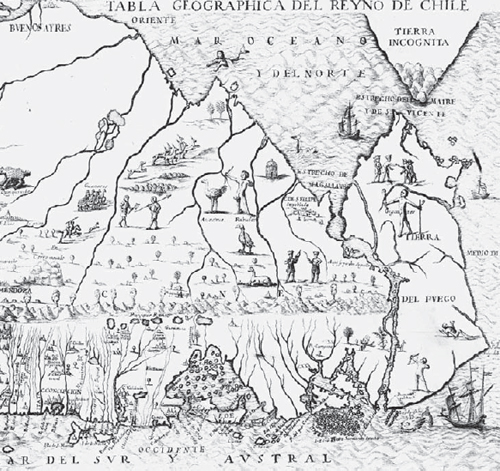

In this late 16th-century chart showing the southern tip of South America, east is at the top. The Magellan Strait, traversed by Drake in late 1577, is on the right, between the mainland and the island of Tierra del Fuego.

Drake was now left on his own. The storm had driven him far to the south, beyond the tip of Cape Horn and towards the icy perils of the Antarctic. When the tempest abated, he worked his way back to the north, hoping to encounter the Elizabeth somewhere off the South American coast. He continued northwards as far as the island of Mocha off the coast of Chile, which he reached on 25 November. This point marked the southern limit of Spanish settlement. He continued on to the small port of Valparaiso, where on 5 December he captured and ransacked a Spanish merchant ship, and pillaged the town. This yielded plunder worth 25,000 pesos, and marked the start of Drake’s piratical cruise.

At this point, Drake paused in a deserted anchorage to repair his battered ship and to take on water. He also built a small pinnace, which he towed astern. She would prove useful in the cutting-out raids that lay ahead. Drake then continued his cruise, and in early February 1579 he appeared off Arica, the port where silver from Potosi was loaded onto ships bound for Panama. There and in the neighbouring small ports he captured a handful of prizes yielding a small quantity of plunder, but nothing of any real value. It seems that the Spanish had warning of his coming, and landed a cargo of silver before he arrived. More importantly though, he captured and interrogated Spanish seamen, who told him that a treasure galleon was on its way to Panama, but was several days ahead of the Golden Hind. This was exactly the sort of rich prize Drake had been looking for. Drake decided to sail north and intercept her.

On the way he looked into Callao, the port serving Lima, the capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru. Once again he found little of any value, and he sped on to the north. However, what Drake did discover from Spanish fisherman was that the treasure galleon – the 120-ton Nuestra Señora del la Concepción – was only a few days ahead of him, and Drake’s ship was faster. Drake had also learned that for some reason the Spanish nicknamed the galleon the ‘Cacafuego’ (lit. ‘shit-fire’), and that she was relatively lightly armed. All he had to do was to catch her.

Late in the day of 1 March 1579 a lookout – Drake’s cousin John – sighted the galleon ahead of them. Rather than cram on sail, Drake had disguised his ship as a Spanish merchantman, and he streamed a kedge anchor astern to slow his ship down. This meant that while he gradually overhauled the Spanish galleon, the suspicions of her crew weren’t aroused. When Drake finally made his move the Spanish were too close to escape. As a result, the Spanish captain San Juan de Anton, was taken completely by surprise.

As he approached the Concepción, Drake hauled down his Spanish colours and hoisted the St George Cross. He called upon the Spaniards to surrender, and when they refused he ordered his men to open fire. The mizzen mast of the Spanish galleon was brought down by the first broadside and within minutes Drake had sent his pinnace across with a boarding party. The Spaniards had no real option but to surrender. What the Englishmen discovered was a wealth of plunder. The hold of the Concepción contained chests filled with silver pesos, some 26 tons of silver ingots and 80lb of gold bars. That was just the official cargo. The total haul was later valued at 400,000 pesos – or £260,000 in English gold – roughly the equivalent of $75 million today. While this represented a mere 3 per cent of the annual total of specie that flooded into the Spanish coffers, it was an unbelievable windfall to Drake and his men, the richest prize of their lives.

All Drake had to do now was to sail home with his plunder, Unfortunately, the Spanish were now well aware where he was, and would be looking for him. The voyage back down the South American coast would take the English through waters that would be patrolled by Spanish warships eager for revenge. Drake decided to avoid the danger by taking the long way home – heading westwards across the Pacific, through the East Indies into the Indian Ocean, then sailing round Africa into the Atlantic, before heading northwards towards home. Drake’s voyage would therefore be a complete circumnavigation of the globe.

Dramatic though this voyage was, the details of it lie beyond the scope of this book. In brief, he continued on to the north, keeping clear of the big Spanish ports of Panama and Acapulco. He sailed up the Pacific coast of North America as far as what is now Canada, possibly in the hope of discovering the western end of the fabled North-West Passage. All he found was ice. He retraced his route southwards to the level of what is now California. Drake spent several weeks there, in a region he dubbed ‘Nova Albion’, possibly in the region of what has become San Francisco Bay. It was from there on 23 July 1579 that he headed west across the Pacific. Two months later he made landfall at an island he called the Island of Thieves, before continuing on towards the Philippines. He skirted them and headed south towards the Spice Islands of the East Indies.

During his voyage of raid into the Pacific Ocean in 1577–80, Francis Drake in his little ship Golden Hind attacked and captured the poorly armed Spanish treasure galleon Nuestra Señora del la Concepción, which was laden with silver and other specie.

After a brief sojourn at Ternate, Drake sailed for England, with six tons of cloves in his hold. Three of these had to be jettisoned when the ship ran aground somewhere off Timor, and it took two months to repair the ship and then cautiously sail her through the maze of islands into the deep blue waters of the Indian Ocean. By late March 1580, the Golden Hind had left Java astern, and ten weeks later she rounded the Cape of Good Hope. On 26 September Drake finally entered Plymouth Sound, after a voyage lasting just over 33 months.

Drake’s first question when coming within hailing distance of a Devon fisherman was whether the Queen was in good health. Whatever her condition, she would have welcomed the news of Drake’s return. After all, the Sea Dog had brought her a substantial return on her secretive investment. Drake found himself feted as a hero, and one of the wealthiest men in Devon. He also found that the country was on the brink of war, a conflict he had done much to bring about.

In April 1581, the Queen honoured Drake by visiting his ship as it lay at anchor in Deptford on the River Thames. She celebrated the event by knighting him on the quarterdeck of the Golden Hind, which had been repainted and draped with bunting for the occasion. This event was a very visible sign that the political climate had changed. By formally acknowledging the man Queen Elizabeth called ‘my pirate’ she was sending a clear signal to the Spanish that English attitudes towards them were hardening. For years Drake and his compatriots had walked a diplomatic tightrope as England and Spain were embroiled in a ‘Cold War’. Now it seemed that the diplomatic gloves were about to come off. This meant that Sir Francis Drake’s private war with the Spanish was about to become part of a larger international struggle.