Drake’s expedition set sail from Plymouth on 14 September 1585. The departure was so hurried that supplies were left on the quayside, and the ships lacked a full supply of water. Stores had been loaded onto the nearest ships rather than the ones they had been earmarked for, and the mess would take time to sort out – yet Drake wasn’t prepared to do so in Plymouth. Once out to sea the die was cast, and there was no possibility of a last-minute postponement or cancellation from the Queen. Drake’s haste is typified by the contract of Captain John Martin, which was hurriedly signed by Drake that very morning amid a rushed bid to sort out all the legal paperwork. It seemed that Drake realized that his raid was a politically sensitive enterprise, and it would take very little to persuade the Queen and his advisors that the whole project was a diplomatic time-bomb.

The island of Hispaniola, from a Spanish chart dated 1568, the year Drake and Hawkins were attacked at San Juan de Ulúa. In this depiction of the island three ships are shown sailing towards Santo Domingo, on the island’s southern coast.

The expedition was the largest force Drake had ever commanded, and while he might have been nervous, this didn’t show when he gathered together his principal commanders and captains on board the Bonaventure late that afternoon, as the fleet lay off the Cornish coast. He gave these officers his final sailing instructions, something that should have been done on shore, before the expedition sailed. He also laid down the law, issuing rules for the good governance of the expedition. This time there would be no repeat of the disharmony of his Pacific voyage.

Christopher Carleill recorded his impression of Drake at the gathering: ‘For my own part I cannot say that ever I had to deal with a man of greater reason or more careful circumspection.’ It seemed that the fiery Drake was learning the value of diplomacy.

Drake’s main concern was his supplies. As we have seen, the rush to leave Plymouth meant that stores were unevenly distributed throughout the fleet, and some vessels were already borrowing casks of food and water from their consorts. Drake refused to put into an English port to sort out the issue, as he still feared a recall from the Queen. The ships were crowded – the formula of one man for every 1½ tons of ship displacement was high, even by the standards of the time. Drake knew that they needed more supplies. He proposed a landing in either Ireland or France, but the latter was preferable, as it involved no risk of running into a royal messenger.

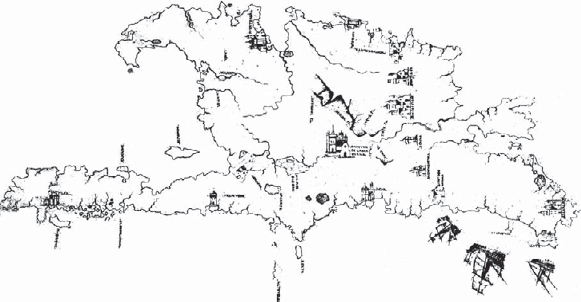

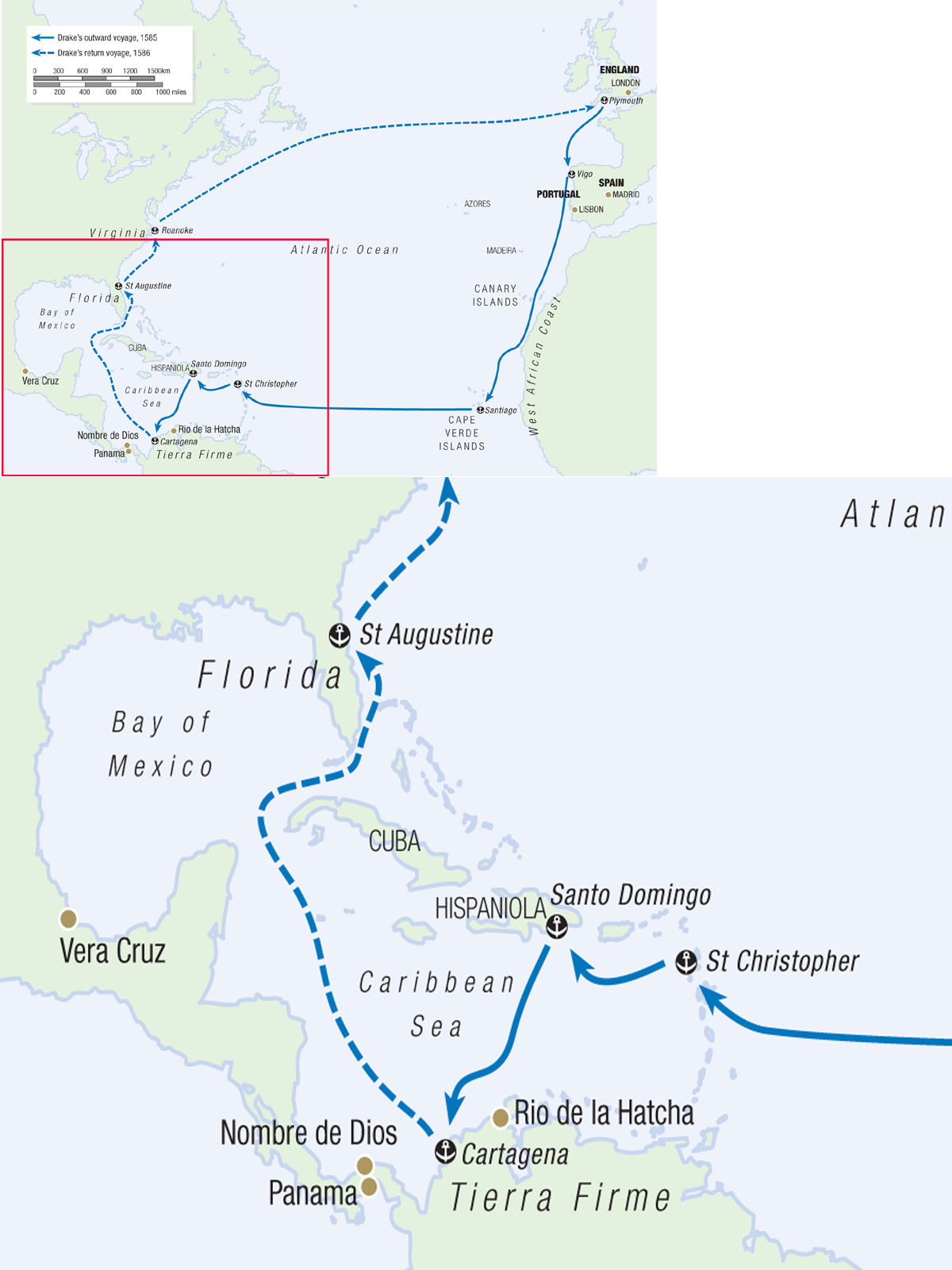

The route taken by Drake on his ‘Great Expedition’.

Drake’s supply problem was sorted out more through luck than anything else. On 22 September, a large Spanish fishing boat was spotted, and the Elizabeth Bonaventure and Tiger set off in pursuit. It was Carleill in the Tiger who overhauled her first, and found that the holds of the Biscayan ship were laden with fish. After these were distributed throughout the fleet, Drake had enough supplies to last until he reached the Spanish coast. Once there he could seize whatever provisions he needed.

Five days later the fleet reached Vigo Bay, in the north-west corner of Spain, and it dropped anchor in the mouth of the River Vigo. The arrival presented Governor Don Pedro Bermudez in nearby Bayona with a problem. One of the most feared enemies of Spain was anchored off the port, and it was poorly defended. Although England and Spain were theoretically at peace, Drake’s appearance suggested he didn’t have peaceful intentions. Without instructions from Madrid, though, Don Pedro was unwilling to open fire. Drake solved the dilemma by offering to negotiate. He sent a messenger ashore, who asked two questions. First, was Spain at war with England? Second, why had the Spanish impounded English ships?

While he waited for his answer, Drake inspected the defences of Vigo and Bayona, and landing parties were sent to nearby islands to take on water. While there they desecrated a Catholic chapel, but Don Pedro was eager not to make an issue of this act. Instead his response was diplomatic. He told Drake that the two countries were at peace, and announced that although English shipping had been seized on orders of the King, the vessels had now been released. The message was accompanied by boat-loads of supplies – bread, oil and wine – a gift from the people of Galicia. He was obviously trying to placate the Englishmen. Drake responded by moving further up the river, so his guns threatened Vigo itself. Actually, this move was forced on the fleet by the weather; a storm was brewing, and they needed to move from their exposed anchorage in the mouth of the river. Don Pedro responded by gathering his militia on the city waterfront – 1,000 men, including cavalry.

With a major diplomatic incident brewing, Drake offered to talk again. He sent two captains ashore as hostages, and in return the Spanish governor was rowed out to meet Drake. The English commander in turn was rowed out to meet him, and in one of the most curious negotiating scenes of all time they talked for two hours, and managed to diffuse the explosive situation. Drake agreed to leave Vigo alone, if he could provision and water his ships without Spanish interference. The English fleet remained off the port for the best part of two weeks, and English sailors brazenly walked through the streets, protected by the firepower of Drake’s ships. During this sojourn, Drake learned that he had missed his opportunity to intercept the returning Spanish treasure fleet. Part of it had returned safely to Seville before Drake had even set sail from England, while the rearguard was due to arrive any day. It seemed that the English were too late.

When Drake’s fleet finally sailed from Vigo on 11 October, Don Pedro Bermudez must have been a relieved man, but he still had to answer for his actions to the King. After all, Drake had dictated terms on Spanish soil, and extorted supplies virtually at gunpoint. Attacks on Spain’s colonies were one thing, but similar incidents in Spain itself were seen as a grave insult – an international humiliation. Worse, the Spanish had no idea where Drake would go next. King Philip ordered that the settlements in the New World be warned that Drake was at sea. The truth is, there was little he could do. While the defences of the Spanish Main were strong enough to resist small groups of interlopers, they were no match for Drake’s fleet. All of Spain’s key towns in the New World were now at risk, and there was no fleet on hand to protect them. It was little wonder that the Spanish viewed Drake as such a fearsome opponent. King Philip’s empire lay at the mercy of a man who had little pity for the Spanish.

Part of the reason Drake lingered so long in Vigo was the weather. A storm was raging, and there was little point putting to sea until it passed, and all the necessary provisions were loaded. Drake still hoped to intercept the rearguard of the Spanish treasure fleet. The English fleet sailed down the Portuguese coast, by which time the flota was just leaving the Azores, having taken on stores and provisions there. That put them 930 miles to the east of Drake. However, the Spanish made a fast passage, and Drake was still off Lisbon when they slipped past the southern tip of Portugal – Cape St Vincent – some 125 miles to the south. From there the flota reached the safety of the Guadalquivir River by the middle of the month. This meant that Drake missed this huge opportunity by less than a day.

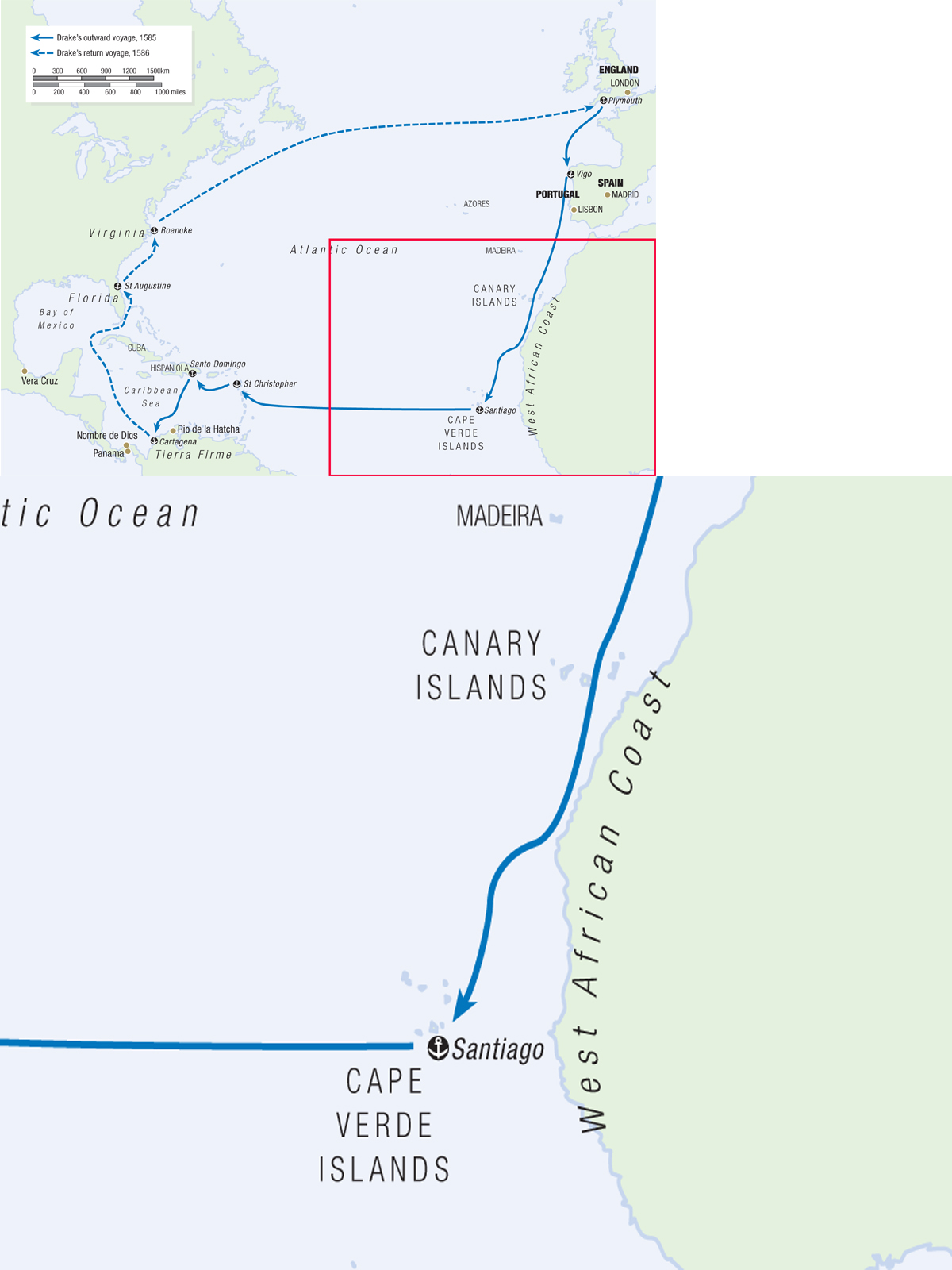

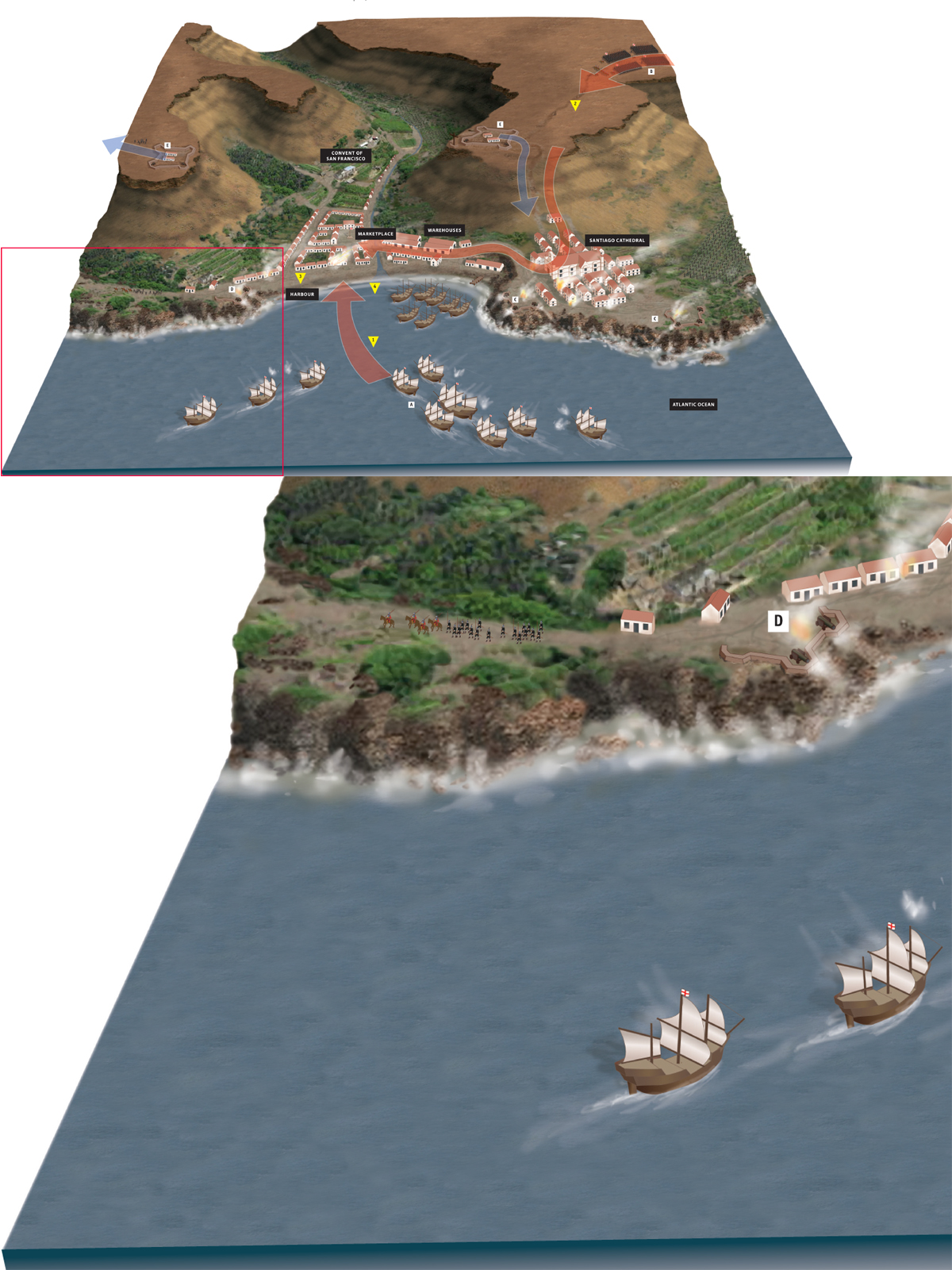

In this engraving by Theodore de Bry depicting Drake’s assault on the town of Santiago in the Cape Verde Islands, the Spanish townspeople are shown fleeing from the English troops advancing from the east, while Drake’s fleet lies just outside the harbour.

11 NOVEMBER 1585

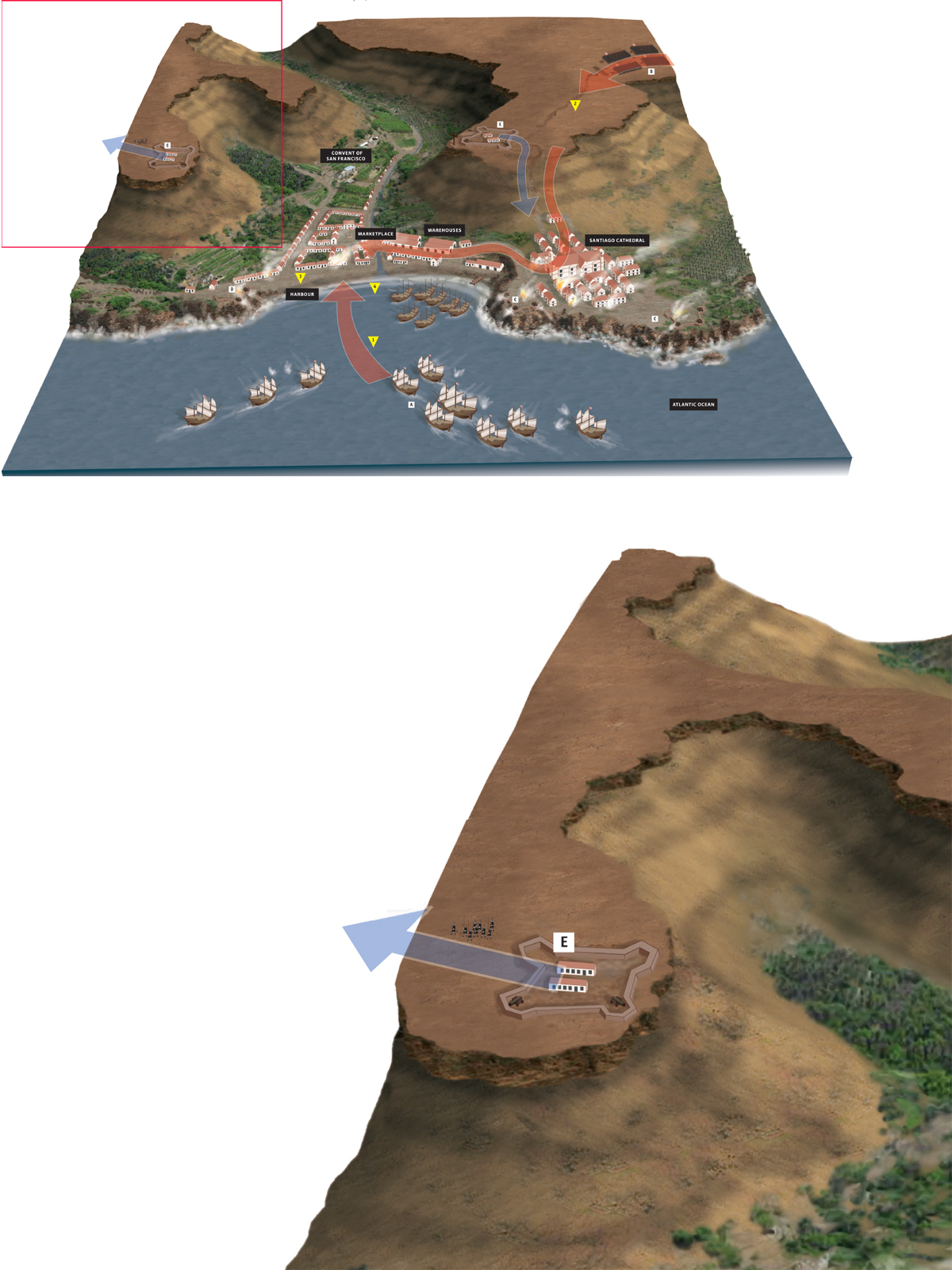

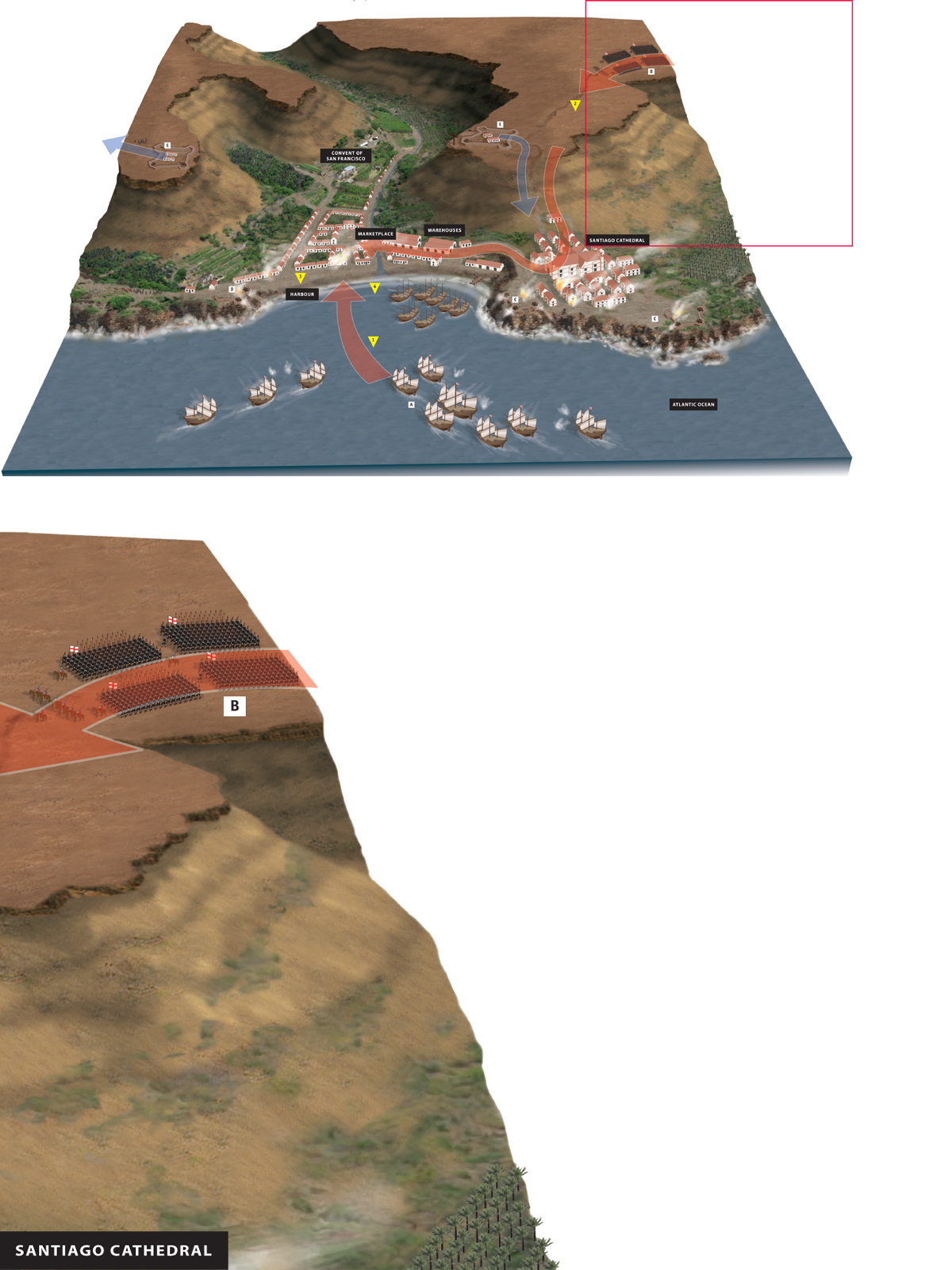

Sir Francis Drake launched his first assault on a Spanish town before he had even crossed the Atlantic. In November 1585, he appeared off the small port of Santiago, the capital of the Cape Verde Islands, which until five years before had been in Portuguese rather than Spanish hands. In this attack Drake demonstrated the tactics that would serve him well in the Caribbean – a naval ‘demonstration’ off the port, while an assault force moved into position to launch a surprise attack from land.

KEY

A English fleet (Drake)

B The English assault force (Carleill) – 1,000 men in 18 companies

C The town’s principal coastal batteries

D Secondary harbour battery

E Spanish earthworks (Fortalezza San Filipe)

|

EVENTS |

1 Around 06.00pm on 10 November, Drake brings part of his fleet as close to Santiago as he dares, and begins bombarding the town’s defences. This was designed to distract the defenders, while Carleill’s assault force landed on a beach 4 miles to the east. The Spanish return fire, but their firing was sporadic, and it soon peters out.

2 At about 4.00am, Carleill’s men appear on the hill to the east of the town. The handful of defenders manning the earthworks there flee through the town. The English troops seize the defences, then storm down the hill, past the cathedral and into the town.

3 Shortly afterwards, the remainder of the Spanish garrison flees along the shore to the west, accompanied by the townspeople, clutching what they could of their possessions. By 04.30am, Carleill is in control of the town, and he plants the English flag in the town’s marketplace.

4 Soon after dawn, Drake and his senior officers row ashore, and take possession of Santiago. The town is comprehensively looted.

The disappointment must have been great. By intercepting all or part of the returning treasure flota, Drake would have struck the Spanish a crippling blow. He would also have earned himself and his country a staggering fortune. Instead he headed southwards to the Canary Islands, where he hoped to take on more provisions before he began his transatlantic voyage.

By 3 November the fleet was lying off Las Palmas, where Drake planned to land and seize whatever provisions and plunder he could find. Unfortunately for the English, the sea was too rough to attempt a landing, and the Spanish gunners plied the approaching English ships with shot. One roundshot narrowly missed Drake and his two leading officers as they stood on the quarterdeck of the Elizabeth Bonaventure. Other hits were scored against the Galleon Leicester and the Aid. Quite sensibly Drake decided to withdraw. Instead he took on water from the undefended island of Gomera, and then continued his voyage, heading south towards the Cape Verde Islands.

These islands were a strange destination. Drake’s orders were explicit – to sail to the Caribbean, and to attack Spanish settlements there. There was no mention of the Cape Verde Islands, a relatively poor archipelago that until five years ago had been Portuguese, but was now controlled by Spain. Drake later argued that he intended to set off from there on his transatlantic voyage. After all, this was fairly common practice. However, a more direct course would have been to use the Canary Islands as a springboard for the Atlantic crossing. It has been argued that Drake needed provisions, as he had been thwarted in taking on stores at Las Palmas. It was also claimed to be a diversion, putting the Spanish off his trail before he descended on the Spanish Main.

A more likely reason is revenge. Three years before, William Hawkins – the father of John and William the Younger – had visited the Cape Verde Islands with seven ships, two of which belonged to Drake or his brothers. Although this was a peaceful trading voyage the Spanish garrison there had launched a surprise attack against the moored English ships, and the elder Hawkins lost several of his men before he could escape to safety. This episode was too much like the humiliation of San Juan de Ulúa for Drake to ignore. In his account of the voyage the Elizabethan chronicler Thomas Cates even claimed that Drake gave his reason for the punitive attack on Santiago in the Cape Verde Islands as being the ‘fresh remembrance of the great wrong they had done to old Mr. William Hawkins of Plymouth, in the voyage he made four or five years before, when they did both break their promise, and murthered many of his men’. Here was little more than a continuation of Drake’s private war.

The town of Santiago (Sào Tiago) lay on the south-west side of the island of the same name, the largest island in the Cape Verde archipelago. It is now called Cidade Velha (‘Old City’ in Portuguese), and at the time it served as a major base for Portuguese slaving operations on the West African coast, and was an exporter of both sugar and cloth. When Drake arrived in November 1585 it had a population of around 2,000 people, and its white-walled and red-roofed buildings were surrounded by lush groves of palm, fig and citrus trees. The town itself lay at the head of a narrow valley, flanked by barren and precipitous hills, and was protected by two batteries that covered the anchorage. These sat on a small headland in the centre of the town, while a third was sited on lower ground to the west, covering the landward approach to the town from the beach. While these defences sounded imposing, they had not been maintained, and offered little protection against Drake and his men.

On the evening of 11 November, Christopher Carleill landed his men in what was almost certainly their first amphibious landing. It would also be their first taste of a night march and night battle. More than 1,000 troops landed without any major mishap, and under cover of darkness Carleill led his men into position on the eastern side of the town, stumbling through the rock and brush as they went. This side of the town was unprotected – the defences were concentrated on its seaward side, covering the anchorage and the beach.

The Baptista Boazio map of 1588 makes Santiago look far more orderly than it really was. However, it shows the harbour was merely a small curved beach, with a small quayside on the western edge of the rocky promontory. It could hold nothing more than a few small fishing boats; anything larger had to anchor further out in the bay. The town sat astride the stream, while the small headland was dominated by a diminutive cathedral, with the stream on its western side. Boazio omitted the church, built in the late 15th century, but marked its location with a small chapel. He also got the hinterland wrong, as the town sat in a hollow surrounded by high, arid hills. In his version, Carleill is advancing towards the town across a level plain, presumably a simplified depiction of the plateau that all but surrounded the small port.

As Carleill moved into position Drake brought up his ships and began bombarding the shore batteries. They fired back, but their response was lacklustre, and soon Drake and his men could see the townspeople fleeing to safety, heading west, away from Carleill and his soldiers. In the end there was no resistance worth speaking of. After a few shots the batteries fell silent, and Carleill marched into an undefended, empty town. The only inhabitants who remained were a few elderly residents, and 26 fever-ridden patients in the slave hospital. By dawn the Cross of St George was flying over the town, and Drake landed to see what the locals had left behind them.

There was little to plunder. The English captured seven Portuguese slave ships lying at anchor off the town. One of them was added to the fleet, while the rest were stripped of anything of value. Drake’s men looted what they could. Old bronze Portuguese guns and equipment were taken from the batteries, silk and cloth were seized from the town’s warehouses, the houses were ransacked for food and the groves stripped of their fruit. Drake’s men even took the bronze bell from the town’s cathedral. Drake sent emissaries to track down some of the inhabitants, as he planned to hold the town and burn it unless the island’s governor paid him a ransom. Nobody came forward to negotiate.

The few locals he captured told him that the governor was in the nearby village of Santo Domingo (São Domingos), a few miles inland. Drake and Carleill led a force of 600 men in a dispiriting trek into the arid hills of Santiago island. The inhabitants of Santo Domingo fled when the English approached, so Drake and his men looted what little they could, then burned the village to the ground. The punitive expedition returned to the coast, shadowed as they went by Spanish cavalry. The only fatality was a teenage English straggler, who was captured and executed by the vengeful Spaniards.

The landing of Lieutenant-General Carleill’s men a few miles to the east of Santiago, from a detail of a one of a series of coloured engravings produced by Baptista Boazio in 1588, to celebrate Drake’s accomplishments during the expedition of 1585–86.

On 28 November, Drake made one last attempt to force the Spanish governor to pay a ransom. He sent Carleill on another expedition 9½ miles along the coast to the east, until he reached the small settlement of Porto Praia (now simply Praia, the capital of the island). Carleill’s arrival coincided with the appearance of Drake and the fleet off the town’s beach at dawn the following morning. Once again the 1,000 or so inhabitants fled to safety, leaving Drake in control of another empty town. Similarly, he ordered it to be razed to the ground, sparing only the town hospital, but there was no plunder worth having.

Drake’s severity was his way of sending the Spanish a message. He wanted to make a handsome profit from his raids, and he was simply telling the Spanish that if they refused to negotiate a ransom with him the English would have no hesitation in destroying any town they captured. Drake probably hoped that word of these events would reach the Spanish Main ahead of him, so that other Spanish townspeople might be more willing to part with their wealth in order to spare their homes. In fact, Drake’s standing orders were designed to protect Spanish property, in an attempt to encourage the payment of a ransom. If any plunder was found it would be kept safe, so it could be distributed equitably.

As Drake’s orders put it:

For as much as we are bound in conscience and required also in duty to yield an honest account of our doings and proceedings in this action ... persons of credit shall be assigned, unto whom such portions of goods of special price, as gold, silver, jewels, or any other thing of moment or value, shall be brought and delivered, the which shall remain in chests under the charge of four or five keys, and they shall be committed into the custody of such captains as are of best account in the fleet.

Back in Santiago, Drake had another problem to deal with. Captain Francis Knollys of the Galleon Leicester was a nobleman who saw Drake as a parvenu. As an in-law of the Earl of Leicester he imagined himself as beyond the reproach of Drake, and for months he had spread discord, questioning Drake’s actions and demanding a greater say in decision making. His diary shows how deeply he disliked both Drake and Carleill, and believed that the pair had deceived him by keeping plunder for themselves. In effect, he was accusing the two commanders of corruption, of robbing their fellow members of the expedition. The problem was brought out into the open on 20 November, when all captains were asked to swear loyalty to their sovereign, and to Drake as her appointed representative. Knollys refused to swear the oath, although he added that he would willingly declare his allegiance to the Queen. The following day – a Sunday – Drake’s chaplain Philip Nichols decried Knollys in his sermon, claiming that anyone unwilling to swear the oath was unworthy of the expedition.

That evening Knollys confronted the cleric at Drake’s dinner table, forcing the admiral to intervene. Drake railed at Knollys, accusing him of inciting sedition – even Drake balked at using the word ‘mutiny’. Knollys replied that it would be best if Drake let him sail off on his own. The following morning, Drake was rowed over to the Galleon Leicester, and called its crew together. He asked them if they preferred to leave the expedition with Knollys, or remain with Drake. All but 40 or so elected to stay. Drake then declared that Knollys and his small band of followers were exempt from further service, and would be given the small Francis to sail home in. First, though, Drake had to protect himself. He demanded a written letter from Knollys, stating that he was prepared to leave Drake’s expedition, and the service of the Queen, and return directly to England. Knollys agreed to two of the points, but refused to admit he was leaving the Queen’s service. That would leave him open to later charges of desertion.

This wasn’t good enough for Drake. He wanted rid of the aristocratic troublemaker, but he didn’t want Knollys undermining Drake’s position in the court. Instead he decided to keep Knollys with him on board the Elizabeth Bonaventure for the time being, where he could be watched. His men were distributed throughout the other ships of the fleet. Once again, Drake’s actions appear draconian, but he was sensitive to insubordination, especially after the Thomas Doughty incident during his Pacific expedition. The whole oath of loyalty was unnecessary, and if it was administered anywhere it should have been done in Plymouth, before the expedition ever set sail. Drake left Santiago within a day of the capture of Porto Praia, but before he did so he ordered the town of Santiago to be razed – a final message to the Spanish. On the last day of November, his ships then headed westward, out into the Atlantic Ocean.

As far as we know, the garrison of the Cape Verde Islands only managed to inflict one casualty on the English – the teenage straggler. However, in reality they managed to inflict heavy losses on the expedition during the weeks that followed. Somehow the English had become infected by a virulent strain of fever, possibly contracted from the patients of the slave hospital. From what description we have of the symptoms it seems that it might have been a form of typhus, which spread through the crowded, unsanitary conditions on board the ships of the fleet. The crew of the Elizabeth Bonaventure suffered particularly badly – within days the majority of her crew were laid low with the fever. In just a fortnight almost a hundred of them were dead, while 60 more deaths were recorded on board the Primrose. The death tolls represented a third of each ship’s total complement. A strict quarantine was enforced, but nevertheless more than 300 English seamen and soldiers died before the fleet made its landfall in the West Indies. The survivors were left weak and debilitated, and in no condition to take part in an assault on a defended city.

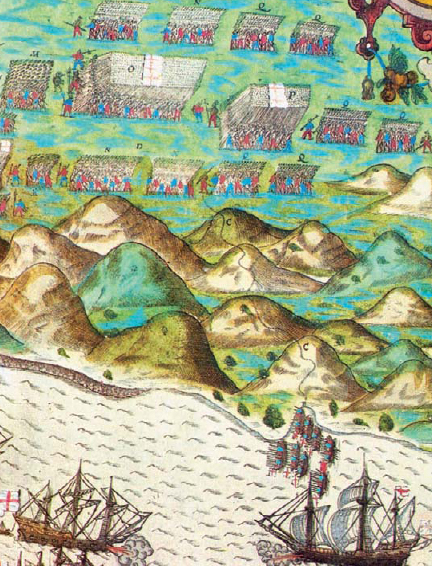

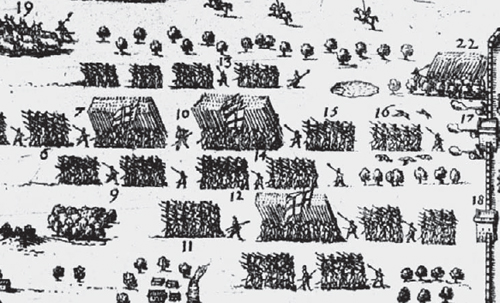

Theodore de Bry’s depiction of Drake’s assault on Santo Domingo is clearly based on the earlier Boazio engraving, but they differ in minor details. The later version, for instance, accompanied an account of the battle, and was therefore annotated with a key.

Around 15 December, Drake arrived off Dominica in the Leeward Islands, where he took on water. He then moved north to the uninhabited St Christopher (St Kitts), where he landed his sick and fumigated his ships. He also probably took the opportunity to careen the vessels, cleansing their hulls of weeds and barnacles. No doubt he also acquired whatever fruit and game his men could find on the island. While all this was going on Drake sent a small scouting squadron off to the west, to conduct a reconnaissance of the Spanish-held island of Hispaniola. Drake intended to make the island’s capital of Santo Domingo his next target.

Santo Domingo was once the capital of Spain’s New World Empire, and it was a small, bustling city, perched on the south-eastern shore of Hispaniola in what is now the Dominican Republic. It was also the oldest Spanish city in the Americas. Known as the ‘Flower of the West’, its attractions included a substantial cathedral, monasteries, imposing civic buildings and shady tree-lined squares. Unlike Santiago in the Cape Verde Islands, this was a real city, worthy of attack. It was also an ecclesiastical, legal and administrative centre, the bureaucratic heart of the Spanish New World. Striking there would send a signal that no Spanish city in the Americas was safe from English attack.

The principal fortification in Santo Domingo was the Fortaleza Ozama, a strongpoint overlooking the harbour, and dominated by the stone keep of the Torre de Homenaje (Tower of Homage) – marked here as ‘26’. Unfortunately for the Spanish, the landward defences of the city were much less formidable.

1 JANUARY 1586

At Santo Domingo, Drake perfected the tactics he developed in the Cape Verde Islands seven weeks earlier. He landed Major-General Carleill’s assault force under cover of darkness, then as dawn rose he appeared off the town with his fleet. He bombarded the town and launched a dummy amphibious landing, and just when the Spanish were convinced the assault would come from the sea, Carleill and his men burst out of the jungle, and stormed the city.

KEY

A English fleet (Drake)

B The English assault force (Carleill) – 1,000 men in 18 companies

C The Fortaleza Ozama

D Spanish militia (de Ovalle) deployed in defence of the beach

|

EVENTS |

1 At dawn (around 4.30am) on New Year’s Day Drake’s fleet arrives off Santo Domingo, and lies just inside gun range of the city’s shore batteries. The garrison already had word of Drake’s impending attack, and three blockships had already been scuttled between the sand spit and the shore, blocking the entrance to the city’s small harbour. The two sides bombard each other, but the Spanish lack reliable powder, and Drake isn’t willing to press the attack. After all, this is only a diversion.

2 The Spanish spend the morning improving their defences on the beach, protecting themselves against an amphibious attack. Many of the defenders begin sneaking back into the city, or run away into the jungle.

3 At noon Drake realizes that Carleill and his men are in place, and so he stages an attempted assault on the beach, to pin the defenders in place. His boats never actually come within small-arms range of the shore.

4 While this diversion was underway, Carleill and his English soldiers appear out of the jungle to the west of the city, and advance into the open, with drums beating and flags flying. The Spanish governor sends forwards skirmish troops to block their path, and stampedes a heard of cattle in the hope of disrupting the English. Both the skirmishers and the cattle soon disappear into the jungle to the north, driven off by fire from the English arquebusiers.

5 At approximately 12.30pm, Carleill storms the Lenba gate and enters the city. A simultaneous assault by his deputy Sergeant-Major Powell also succeeds in capturing another gate, closer to the beach. The English are now inside the city.

6 By 3.00pm the only Spanish force left in the area is the garrison of the Fortreza Ozama, which holds out until nightfall. At that point the defenders escape to safety across the river, under cover of darkness.

7 By nightfall Drake and the bulk of his men have landed from their ships, and while his men pillage the city, Drake establishes his headquarters inside Santo Domingo Cathedral.

Santo Domingo was fortified on its landward side by a city wall built in the early 1500s, its line punctuated by small turrets and gun positions. The Fortaleza Ozama – a strongly stone-built castle – overlooked the entrance to its small harbour, and although it was first built in 1503 its defences had been improved and updated over the intervening decades. The most significant of these later additions was a substantial gun battery on the southern face of the fort built in 1571, overlooking the seaward approaches to the town. A striking feature of the castle was the Torre de Homenaje (Tower of Homage), a stone keep dominating the mouth of the harbour. A small sandbar also protected the entrance to the harbour, forcing ships to pass close under the guns of the fort before they could reach the anchorage. A secondary gun battery covered the north-east approaches to the town.

The governor, Cristóbal de Ovalle, declared it to be amongst the strongest forts in Christendom, and it was certainly well provided with artillery batteries, covering its landward and seaward approaches. Unfortunately for the Spanish, these defences were less imposing than they appeared. Many of the guns were mounted on carriages whose woodwork was rotten, rendering them useless. The fort’s magazines were almost empty, and what little powder stored there was reputedly of such poor quality that the few guns capable of firing lacked the power to fire much further than the sandbar.

Another weakness was that the Audencia of Santo Domingo lacked a regular garrison. The only troops available to it were the city militia, a force of as many as 800 men, up to 100 of whom were mounted. Civic volunteers would flesh out their ranks in time of need. Cristóbal de Ovalle, who was also the president of the Audencia and the Captain-General of Hispaniola, claimed that he had 1,500 men available to him, a mixture of militiamen and townspeople. A Spanish chronicler later described these defenders as ‘a few residents with pikes and lances which they had inherited from their fathers or grandfathers, conquerors of the land, and a few harquebusiers, though without gunpowder, bullets or other ammunition’. They would be no match for Carleill and his English soldiers.

At Santo Domingo, Drake landed Carleill’s men on the Bajos de Haina (Haina Beach), and was guided through the treacherous reefs and sandbars lying off the Haina River mouth by a renegade pilot. Detail of the De Bry engraving.

After a week at St Christopher, Drake set sail again, leaving 20 freshly dug graves behind him, the last of his fever victims. He must have encountered his reconnaissance squadron as he sailed westwards, who told him that Santo Domingo looked too formidable to assault from the sea, but that they had found a good landing beach at the mouth of the River Haina, about 10 miles further to the west. That opportunity dictated Drake’s plan – after landing Carleill and his men on the Bajos de Haina (Haina Beach), Drake would distract the Spaniards by threatening an attack from seaward. Carleill would then storm the unsuspecting defenders from the west. Drake had another stroke of fortune. He captured a handful of prizes during his voyage from St Christopher, including a vessel sent from Spain warning de Ovalle that Drake might attack him. He therefore knew that the Spanish at Santo Domingo weren’t expecting him. He also captured a Spanish pilot, who warned him that the mouth of the Haina was protected by reefs and pounding surf, but he offered to help Carleill put his men ashore safely, no doubt encouraged by the threat of what Drake might do to him if he refused to co-operate.

Better still, Drake learned a little more about the city’s defences. Apparently the governor was more concerned at the prospect of a slave rebellion on the island, supported by the remnants of the local Carib Indians. Work had begun improving the crumbling western and northern defences of Santo Domingo, but a lack of funds and skilled labour meant that work had barely begun. Only a small section of the new defences had been completed around the western gate. The rest were barely high enough to prevent animals entering the city, let alone a determined band of armed men. The naval defences of the city consisted of one small patrol galley, and it was considered largely unseaworthy. Better still, the surf off the Bajos de Haina was considered so dangerous that they thought a landing there was impractical. Consequently the beach wasn’t guarded, nor was the path through the jungle that led from it towards the city.

In this detail of Theodore de Bry’s engraving of the English assault on Santo Domingo, Christopher Carleill’s soldiers are shown advancing on the town, with blocks of pikemen flanked and preceded by smaller bodies of arquebusiers.

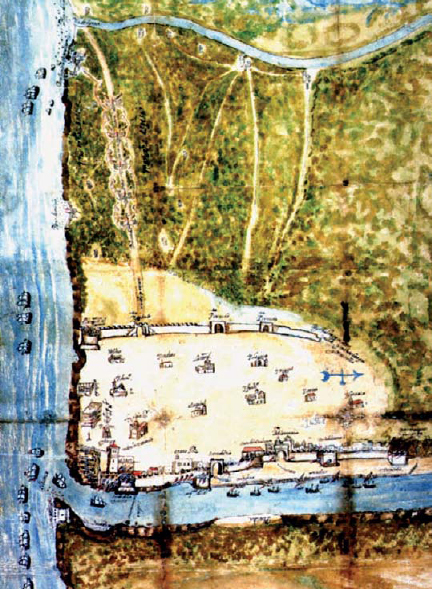

In this unusual coloured depiction of Santo Domingo and its environs, east is at the top of the map, where the landing place used by Drake at the mouth of the Haina River can be seen, with a track leading from it towards the town.

In this detail of a chart of Hispaniola drawn up in the early 17th century, the landward defences of Santo Domingo are no longer shown, while the Fortaleza Ozama (marked ‘A’ on the chart) protects the harbour from attack.

Just after midnight on 1 January 1586 Drake arrived off the Bajos de Haina, and Carleill and his soldiers were safely set ashore. Drake accompanied the pilot as he guided the pinnaces through the reefs and surf, before returning to his flagship. Then the fleet sailed the 10 miles along the coast to Santo Domingo, so that Drake could see the city’s defences for himself. By that stage a local fishing boat had already brought Cristóbal de Ovalle the news that a fleet was approaching, but by then it was too late. Troops were mustered, and three ships were sunk across the mouth of the harbour, to prevent any attempt to force the entrance. The small galley was stationed behind the sandbar, ready to fire on any English ship that tried to clear away the wreckage. Work began on building earthworks to defend the shore, and guns were wheeled into place to reinforce the seaward defences. It was all too little, and much too late. As labourers worked on the defences, many of the townspeople began slipping out of the city.

As dawn rose on New Year’s Day, Drake’s ships lay off the mouth of the harbour, just within artillery range. That was when Drake realized that the enemy’s powder wasn’t up to the task. One roundshot hit the Elizabeth Bonaventure, but most of the balls fell short. Drake ordered his ships in closer, and soon they began firing at the castle and the unfortunate militiamen in the rudimentary earthworks. With the Spanish distracted, Carleill and 800 soldiers approached the city, and by noon they were in position. As Drake made a show of attempting a landing by way of a diversion, Carleill and his men swept out of the jungle, appearing on the right flank of the Spanish militia with flags flying and drums beating. Cristóbal de Ovalle sent forward a skirmish line of cavalrymen and arquebusiers to protect his flank, but these were quickly driven back by English fire. Next he tried herding cattle towards the English formations, but the animals simply ran off into the jungle. Within half an hour, the landing party had reached the western walls of Santo Domingo, and the majority of the city’s militia were in flight.

The western defences were pierced by two gates: the Lenba (the main gate) and a secondary one, closer to the beach. By that stage there were scarcely 300 Spaniards left under arms, and most of them were woefully equipped with pikes and swords rather than firearms. Carleill ordered Sergeant-Major Powell to assault the secondary gate with a storming party, while the lieutenant-general led the rest of his men towards the Lenba. The defenders melted away, and neither column met with any serious opposition. The English were now inside the town. They began hunting the Spanish troops through the streets, heading towards the Fortaleza Ozama. While a small group of Spanish troops held out behind its walls, the remainder of the city was captured without any opposition. During the assault Carleill only suffered four casualties, and given the lack of serious resistance the Spanish losses were probably equally light.

Cristóbal de Ovalle had missed most of the battle, having fled the field soon after Carleill’s men appeared on his flank. He later claimed that his horse had fallen in the muddy streets, and he had returned to his home to change his clothes before returning to the fray. The truth is he fled the city so precipitately that he left his wife behind, who became Drake’s principal hostage. The fortress held out until nightfall, but under cover of darkness the remaining garrison slipped away by boat, and by dawn the English flag was flying over the Torre de Homenaje.

Drake ordered his men to repair the city’s defences, in case of a Spanish counter-attack. Meanwhile their shipmates went on a looting spree, taking what they could from private homes, rifling through the civic offices and stealing the ornaments from the churches. The churches were singled out for special treatment: statues and windows were smashed, religious tapestries ripped down and altars desecrated. If Philip II wanted a religious crusade, Drake and his men would give it to him. The cathedral was spared the worst of these excesses only because that was where Drake set up his headquarters.

The plunder was disappointing. While plenty of goods were captured, including food and wine, only 16,000 gold ducats were recovered from the Audencia’s treasury – the equivalent of 32,000 pesos. Fortunately, Drake knew that this time the Spanish would be more willing to negotiate a ransom, in return for the saving of their town and the lives of his prisoners. On 12 January the head of the city judiciary, Juan Malarejo, approached Drake as the representative of Governor de Ovalle and the Audencia. Drake began the negotiations with a ludicrously high demand of a million ducats. Malarejo pleaded civic poverty, and as talks continued Drake ordered civic buildings and churches to be put to the torch, one after the other. The aim was to apply extra pressure on the unfortunate Malarejo, who returned to consult with his fellow officials. During the days that followed his men began demolishing the city’s imposing stone buildings, even though they lacked the tools to make much of an impression.

The next Spanish negotiator was Garcia Fernandez de Torrequemada, the royal factor on Hispaniola. He proved even more stubborn than Malarejo, and after a week the best Drake could secure was a ransom of 25,000 ducats – or 50,000 pesos. It was far less than Drake had hoped, but he needed to continue his campaign of destruction. The deal was agreed, and Drake promised to spare what remained of the town and sail away from it if the ransom was paid promptly. In his report to the King, Torrequemada included his assessment of Drake:

Francis Drake knows no language but English, and I talked with him through interpreters in Latin or French or Italian. He had with him an Englishman who understood a little Spanish, and who sometimes acted as interpreter. Drake is a man of medium stature, fair-haired, heavy rather than slender and jovial yet careful. He commands and rules imperiously, and is feared and obeyed by his men. He punishes resolutely. He is sharp, restless, well-spoken, inclined to liberality and to ambition, vain, boastful, and not notably cruel. These are the qualities I saw in him during my negotiations.

The comment about resolute punishment was soon put to the test. During these negotiations, Drake sent a delegation to the Spanish camp with a message. The party included a black boy who had joined Drake’s force after the capture of the city. Although they approached the Spanish under a flag of truce, the boy was stabbed and killed by one of the Spaniards, possibly because he was recognized as a runaway slave. The dying boy was taken back to the city, and died in the cathedral, in front of Drake. The English commander was furious – it was said that nothing he did before or since ever matched his fury that day. He responded by having a gallows built within sight of the Spanish. He then had two prisoners brought out – Dominican monks – and they were hanged in full view of their horrified countrymen. A third prisoner was sent to the Spaniards, explaining why Drake had hanged the two clerics, and demanding they execute the murderer of the boy. Two more prisoners would be executed every day until the culprit was punished. The Spanish had little choice but to comply, and the murderer was duly executed within sight of the city.

Meanwhile, Drake solved the problem of Francis Knollys. The two men met on 10 January, and Drake offered Knollys a way out. If the captain swore the oath of loyalty, then Drake would pardon him, and name Knollys as his rear-admiral – second-in-command of the fleet after Vice-Admiral Martin Frobisher. Amazingly, Knollys refused the offer, and demanded to be sent home in the Bark Hawkins. Drake therefore rescinded the offer, and Knollys remained under house arrest until after the attack on Cartagena, by which time the expedition was returning home anyway. Fortunately, Drake’s success at Santo Domingo meant that Knollys no longer posed a threat to the admiral’s authority, and so he was able to ignore the peevishness of his subordinate.

The ransom was finally paid during the last days of January, and on 1 February the English sailed away from Santo Domingo, having occupied the city for exactly a month. A third of the city lay in ruins and almost all of its civic, military and religious buildings had been either damaged or destroyed. Upwards of 20 ships in the harbour were burned, and three vessels were commandeered by Drake to replace three small English ships that had to be abandoned as unseaworthy – the Hope, the Benjamin and the Scout (these were amongst the scuttled vessels). At least Cristóbal de Ovalle was reunited with his wife, although their home had been gutted. Garcia Fernandez de Torrequemada summed up the mood of the population in his report to the King: ‘This thing must have had divine sanction, as punishment for the people’s sins.’ Drake certainly thought he had God on his side, albeit a Protestant rather than a Catholic one. It would take decades for the city to recover from Drake’s onslaught.

In this depiction of the assault on Santo Domingo, a detail from the engraving by Baptista Boazio, the artist has shown several stages of the action – the landing (bottom left), the approach march by Carleill and Drake’s bombardment of the city’s seaward defences.

As Drake disappeared over the horizon, news of his attack spread from Santo Domingo to other cities on the Spanish Main, warning that the Englishman was likely to descend on them. The trouble was, in whatever city Drake chose as his next target, the English fleet would outrun the news, and arrive there first. Within a month news of the attack had reached the Spanish King, who had difficulty working out exactly what had been happening. He was being bombarded by conflicting accounts – Drake had been repulsed from the Canary Islands, he had burned half of Santiago island, his expedition was ravaged by disease, he had freed the slaves of Hispaniola, and he had sacked the ‘Jewel of the West’. Other less accurate rumours claimed he had sacked other cities, including Havana, Cartagena and Vera Cruz. Even Pope Sixtus V heard the rumours, and explained, ‘God only knows what he may succeed in doing.’ Drake had become the talk of Europe.

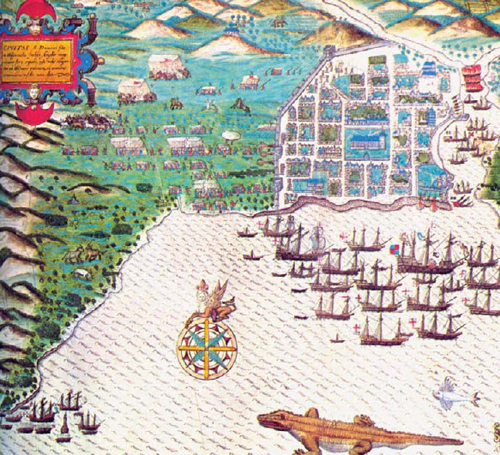

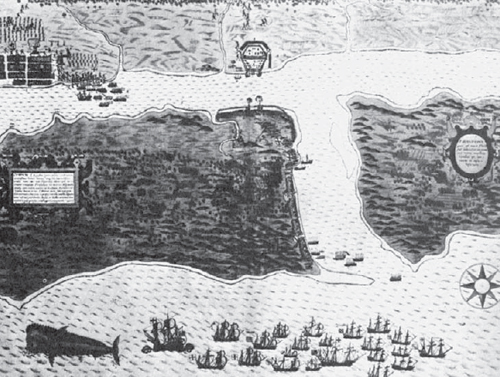

The small city of Cartagena on the Spanish Main, as depicted in a detail from an early 17th-century chart. After Drake attacked it in 1586, the original town (I) was rebuilt, and expanded onto the small island in the salt marsh (1).

In fact, Drake was heading south towards Cartagena des Indies, the largest city on the Spanish Main. His original intention was to attack all the ports along the Spanish Main in turn, but his losses through disease made a protracted campaign inadvisable. Many of his men were still recovering from their fever, and a lengthy stay in such unhealthy waters was considered too great a risk.

Cartagena was the key to the Spanish Main. It was a major treasure port where gold and emeralds were stored, ready for shipment to Spain in the Tierra Firme flota. While the city itself was smaller than Santo Domingo, it was better defended, and Drake predicted that since his last visit to the port a decade before its defences would have been strengthened. While he didn’t expect to extract a great deal of plunder, the capture and sack of Cartagena would be a major humiliation for the Spanish, and it would demonstrate that nowhere was safe from Drake and his men.

The trouble was, the inhabitants of Cartagena already knew he was coming. The first word of the English threat came from Seville – a galleon had been sent with a warning after Drake left Vigo. Then, while Drake was in Santo Domingo, a fast boat had sailed to Cartagena from Puerto Plata on the northern side of Hispaniola, bearing news that the city had been plundered, and warning them that Cartagena might be next. Governor Don Pedro Fernandez de Busto decided to take no chances. Anything of value was transported inland, while the city itself was evacuated of all non-essential residents or soldiers. Don Pedro Fernandez called for reinforcements from elsewhere in Venezuela, and the militia of Cartagena was mustered, equipped and drilled. Weapons were gathered and checked, fortifications were repaired and strengthened, and scouting craft were sent out to patrol the coast, and to provide warning of any approaching fleet. The governor was wise to be so cautious. Drake was on his way.

The English fleet made landfall on the Tierra Firme coast near Rio de la Hatcha, 240 miles to the west, then sailed along the coast towards Cartagena. This meant that Don Pedro had ample warning of Drake’s approach, and reinforcements were ordered to the city, ready to defend it against a sudden assault. Drake knew Cartagena fairly well, having raided its harbour a decade before. He knew that the coast was a treacherous one, as the prevailing north-easterly winds made it hard for a fleet to anchor off the city. Not only were anchors likely to drag, but in a storm the vessels would face the perils of a lee shore, and would therefore need to claw their way out to the safety of the open sea.

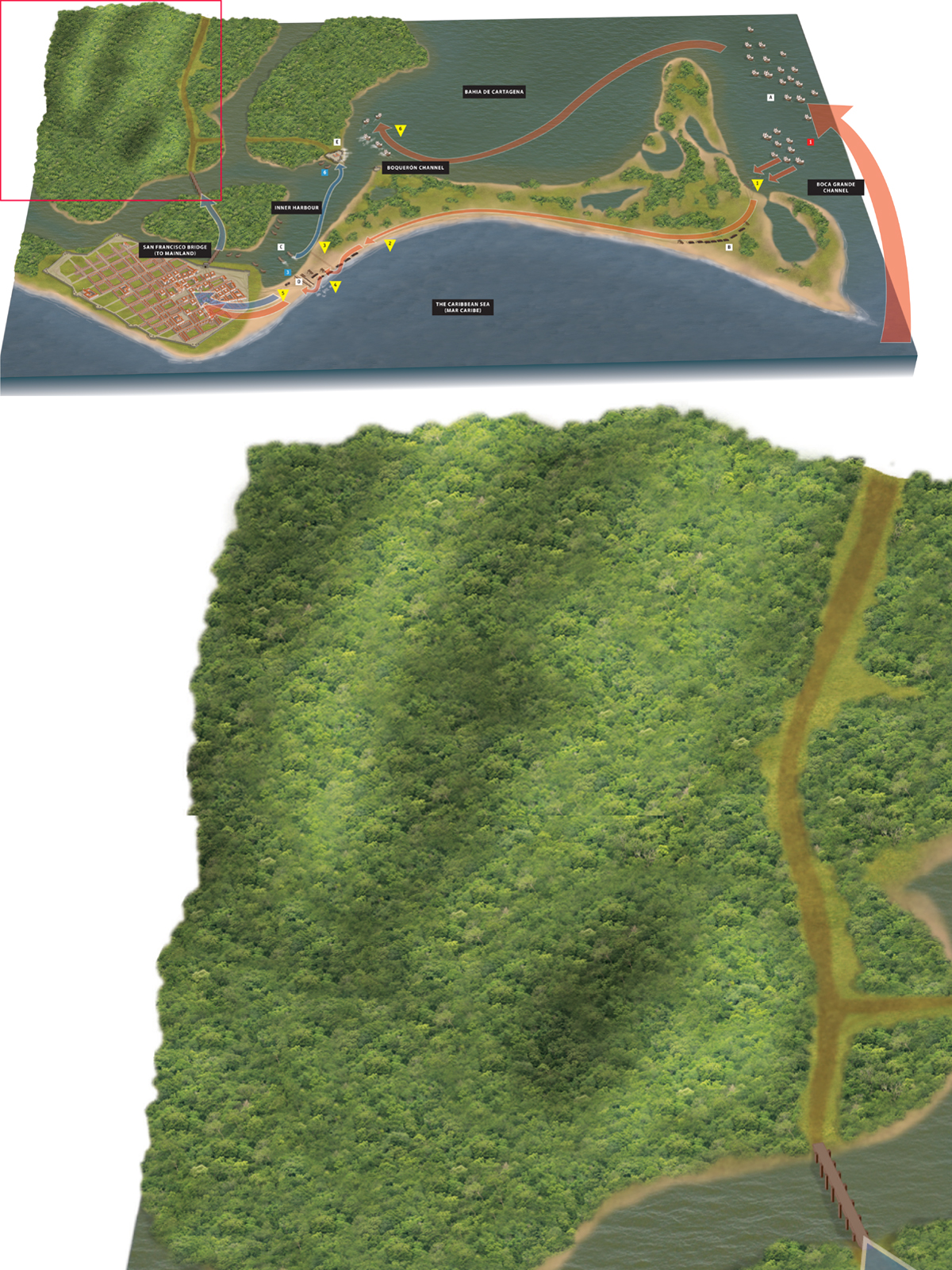

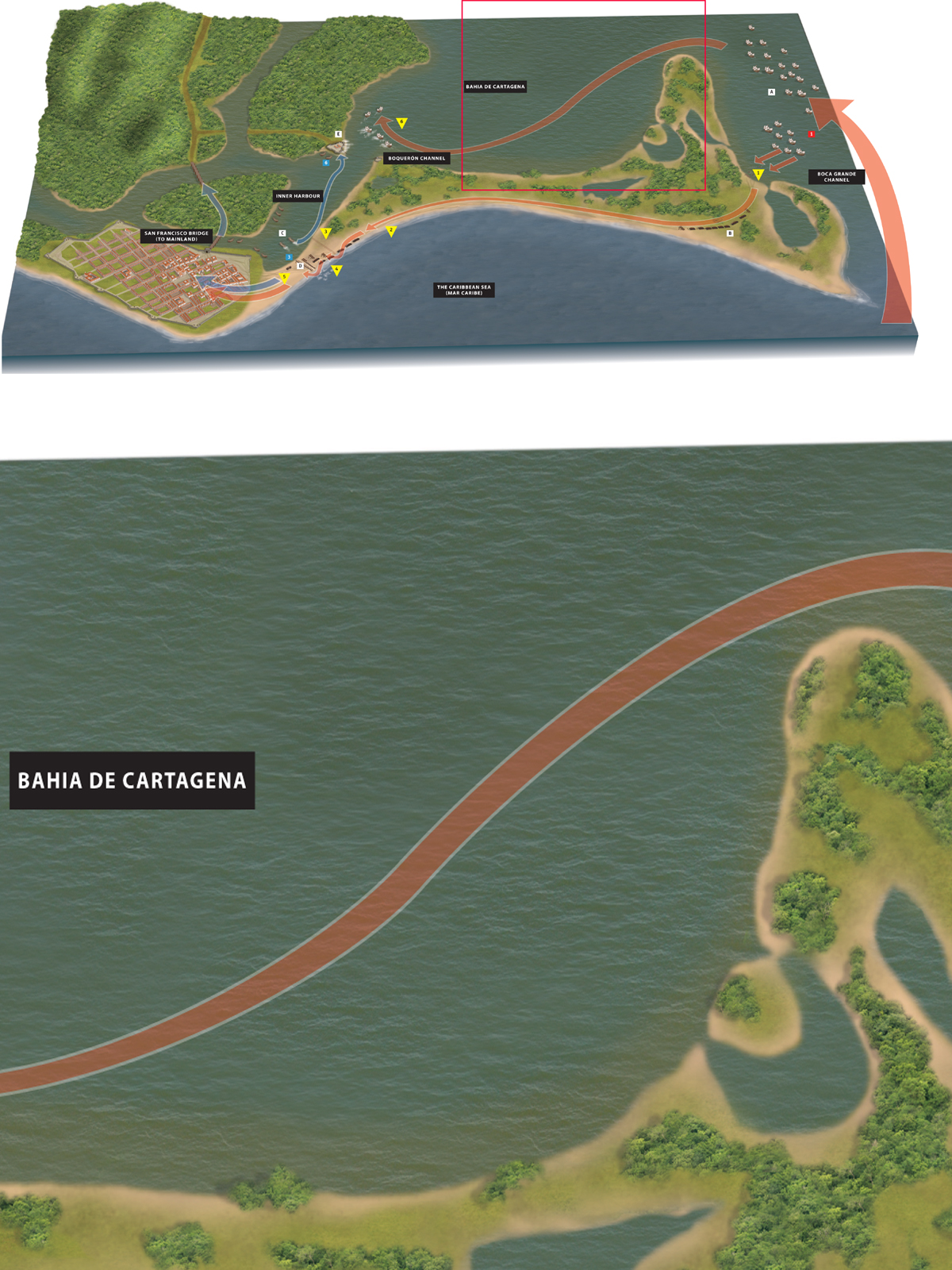

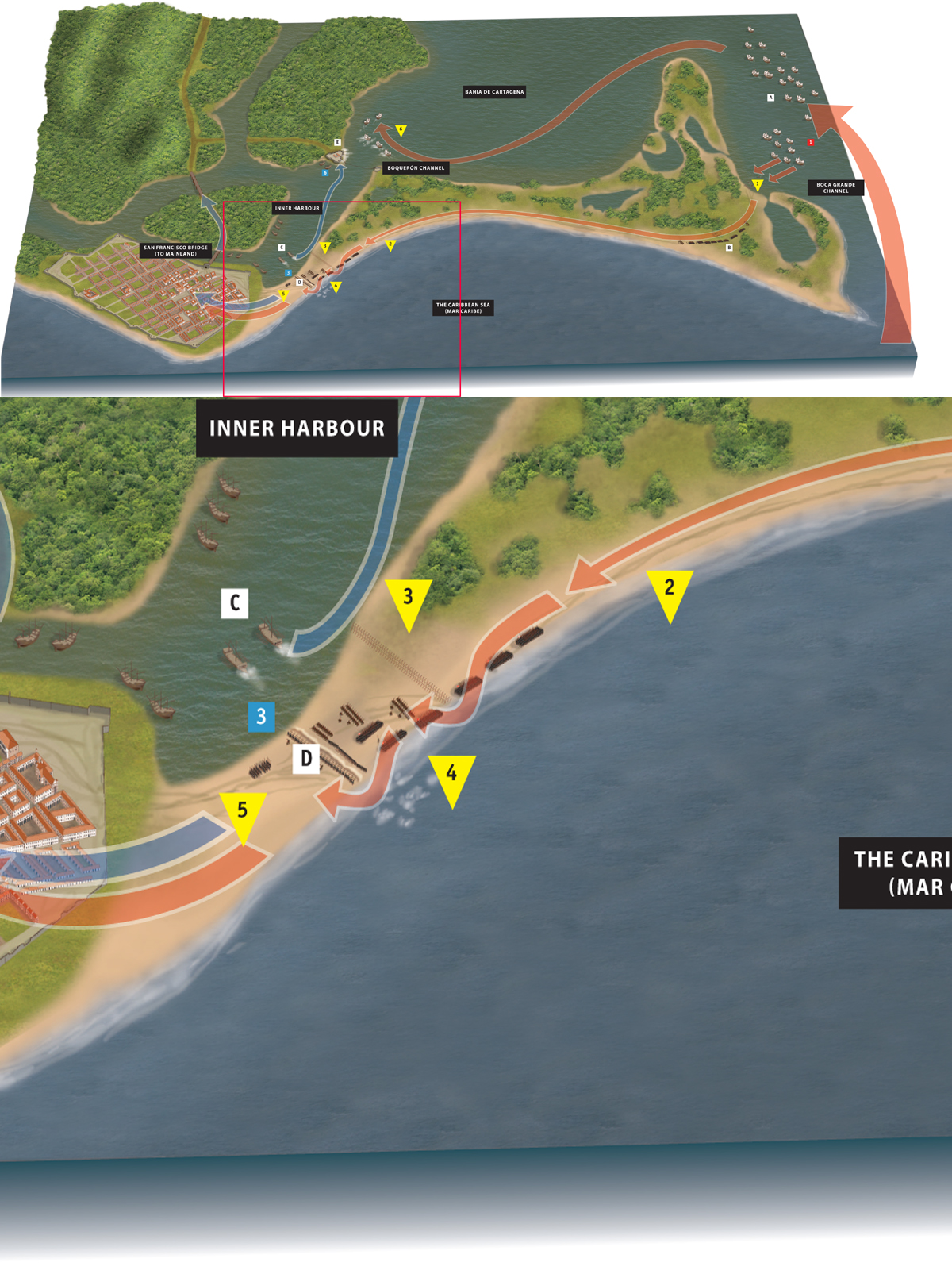

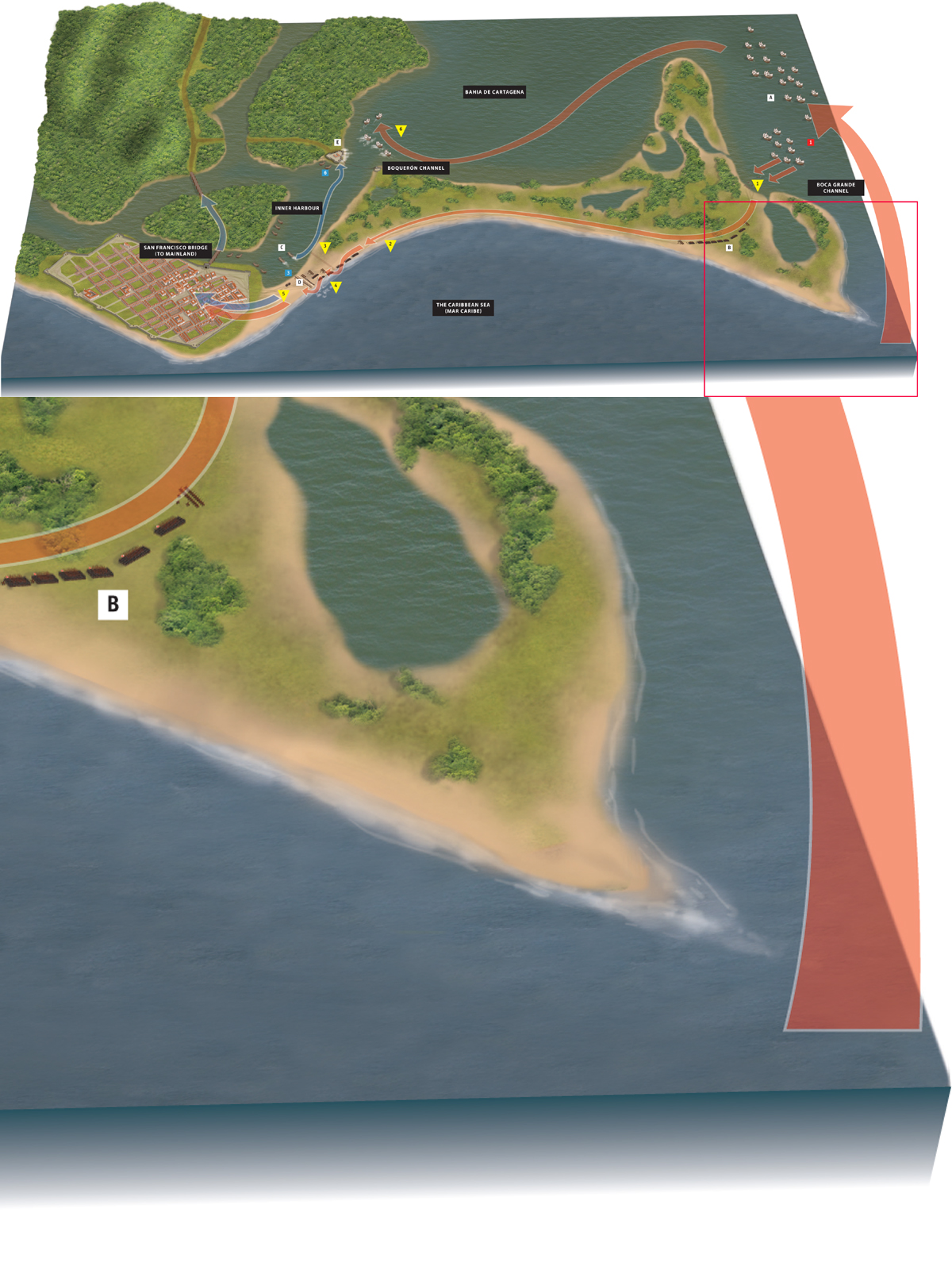

Drake knew he needed to force his way through into one of two narrow channels, to reach the safer waters of the Outer Harbour. These channels – Boca Grande to the north and Boca Chica to the south – lay at either end of an island, now called Tierrabomba. While neither channel was fortified last time Drake was there, he fully expected the Spanish to have done so by now. The Outer Harbour was a sheltered anchorage about 6 miles long and 2 miles wide. The city itself lay at its northern end, which meant that once they breached the defences of the Outer Harbour, Drake’s ships could anchor out of range of the Spanish guns, and he could plan the assault at leisure.

Cartagena lay on the coast, but it was well protected from attack on its seaward side, and the water there was too treacherous to permit a safe amphibious landing. The geography of the area was unusual. The city lay at the base of a narrow S-shaped spit of sand called La Caleta, which divided the Outer Harbour from the Caribbean, and which ended at the Boca Grande Channel. Another smaller island formed a bottleneck at the northern end of the Outer Harbour, and beyond this narrow channel – the Boquerón Channel – lay a small Inner Harbour, the main anchorage. The Inner Harbour was barely a mile long and half a mile wide, and the city itself formed its northern shore. Between Cartagena and the Venezuelan mainland, a seawater-filled moat had been dug, crossed by the fortified San Francisco bridge. To the east the land was swampy, and the wonderfully named Hanged Man’s Swamp separated the city from the jungle-clad hills of the mainland. A single path wound its way through the swamp towards the fortified bridge, making a landward assault extremely difficult.

Drake appeared off Cartagena during the afternoon of 9 February 1586. He sailed right past the city itself, watched by the Spanish militia deployed along the city walls, and on the beach beyond. Drake was delighted to discover that the Boca Grande passage was unfortified, so his ships passed through it in a long column, with the Elizabeth Bonaventure in the lead. The English ships dropped anchor at the northern end of the Outer Harbour, just beyond the range of the Spanish guns guarding the Boquerón Channel. This passage into the Inner Harbour was guarded by El Boquerón, a stone-built fort with eight guns on its eastern side, commanded by Captain Pedro Mexia Mirabel. A chain boom ran across the entrance, protected on the La Caleta side by earthworks, supported by two small but well-armed galleys, the Santiago and the Ocasión. That afternoon, Drake sent Frobisher forward to probe the defences using small boats and pinnaces, but the English were driven back by a heavy fire from El Boquerón. Drake would have to come up with another plan.

Drake still had the best part of 1,800 men available, almost half of whom were soldiers. The number of troops available to Don Pedro Fernandez de Busto is harder to ascertain. Some 300 men crewed the two galleys, under the direct command of Don Pedro Vique y Manrique, who also doubled as the governor’s military advisor. He was assisted by his two subordinates, Captain Juan de Castaneda in the Santiago and Captain Martin Gonzales in the Ocasión. (The crew figures didn’t include a similar number of galley slaves, who were chained to their oars.) The fort of El Boquerón was garrisoned by about 200 men, mainly militia gunners, supported by a handful of Spanish regulars who served as officers and instructors. Another force of up to 570 militia protected the city itself (100 of them being pikemen), supported by a troop of 54 mounted lancers under the command of Captain Francisco de Carvajal, and a unit of as many as 400 Indian allies, equipped with bows and poisoned arrows. Compared to the force available to Governor de Ovalle in Santo Domingo, this was a veritable army.

The big difference between the two sides was morale. Drake and his men were buoyed up by their easy victories at Santiago and Santo Domingo, and they expected to win. Even the experienced soldier Don Pedro Vique recounted that despite the governor’s speeches and the fact that they were defending their homes, neither man could instil much fighting spirit into the militia. Another disadvantage was they had no idea where Drake would launch his assault. This meant that troops had to defend El Boquerón and the Inner Harbour, the long spit of La Caleta and the city itself. By contrast, Drake and Carleill could mass their assault force for one decisive thrust towards the city.

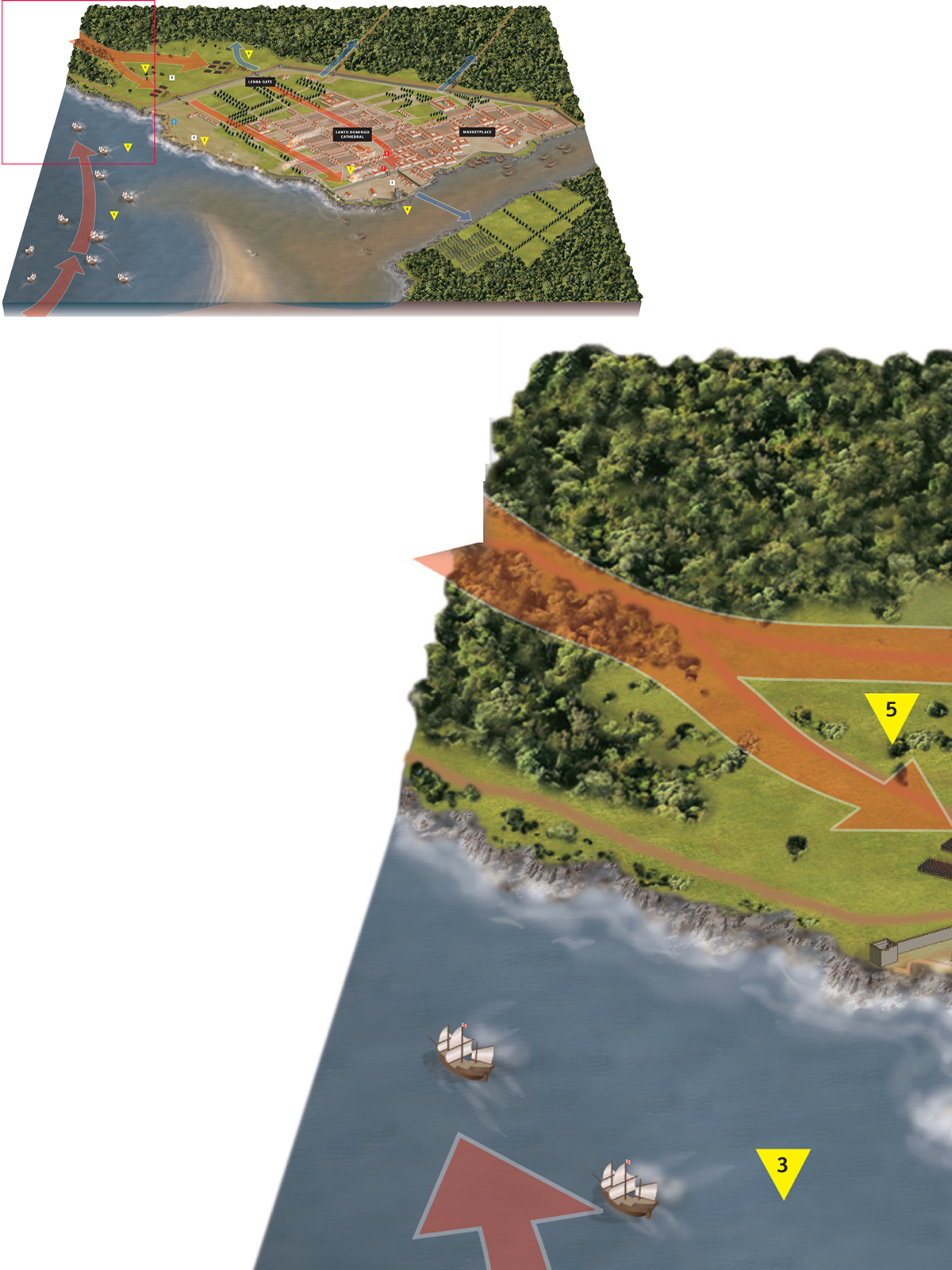

At Cartagena, the English stormed the city’s defences in a dawn attack. Despite being supported by fire from two galleys, the defenders were quickly routed, and the Englishmen poured into the city. Detail of a coloured engraving by Baptista Boazio.

The governor decided to concentrate the bulk of his forces on La Caleta, between the Inner Harbour and the sea. There he ordered a line of entrenchments to be built, to protect the city behind him. The approach to these entrenchments was up the sandy spit, and the final stretch before the Spanish lines would be swept by gunfire from the two galleys patrolling the waters of the Inner Harbour. That way the superior numbers of the English could be offset by Spanish firepower and fortifications. Behind the earthworks the city itself was virtually defenceless. Despite being in office since Drake’s last visit to Cartagena a decade before, Don Pedro Fernandez had failed to improve the city defences. Many of the guns were incapable of being fired, and the city walls were in a bad state of repair. Worse, on the southern side, facing La Caleta, the walls were virtually non-existent. If the English captured the earthworks, the city was bound to fall. Drake knew about these entrenchments, but he still thought that his best chance of capturing the city was by advancing up La Caleta. Carleill agreed, and together they concocted their plan.

Late in the evening of 9 February, the troops clambered into a cluster of waiting boats, and they were rowed across the Boca Grande Channel to a beach on the southern end of La Caleta. At that point the spit formed a dogleg, and Carleill landed his men near its joint, at a beach know as La Punta del Judío, now the Playa de Castellgrande. Amazingly, the Spanish had failed to post sentries, relying on mounted patrols and Indian scouts to warn the garrison of any attempt at landing. For some reason the patrols never appeared until it was too late. During the small hours of 10 February almost 1,000 English soldiers and sailors were landed safely, and formed themselves up into attack columns. Drake landed with them, then returned to his ships to organize a naval diversion. Carleill’s men made their way up the scrub-covered sand spit without being observed, pausing to avoid the poison-tipped stakes the Spanish had emplaced there to impede progress. As the tide was out they were able to bypass these defences by wading through the surf.

The alarm was raised at around 4.00am, when they were within half a mile of the entrenchments. There La Caleta narrowed to just 150 yards, and spanning it was an earthen wall and parapet, with a ditch in front of it. A battery of four heavy guns covered the approaches, and Carleill could see the two Spanish galleys moving into position to blast him from the flank. Then he spotted the weakness. The Spanish hadn’t had time to extend the line of entrenchments beyond the high tide mark on its western or seaward side. After all, they would have found it impossible to dig a trench there. As the tide was out this meant that there was a gap at the end of the Spanish line. The defenders had made a half-hearted attempt to plug it using wine casks filled with sand, but the defences there were unfinished.

Better still for the English, the slight slope of the sand spit meant that the beach was unprotected by the covering fire from the galleys. At least 300 Spanish militia and 200 Indian allies lined the defences, more than one man for each foot of earthen wall. That was when the galleys began to open fire, joined by the defenders of the earthwork. According to Carleill one defender yelled out ‘Come on, you heretic dogs’, suggesting that at the start of the battle at least, the defenders felt they could hold their assailants at bay. Carleill also noted that the galleys were firing too high, as their shot whistled over the heads of the English troops. That was the moment when he gave the order to charge, yelling ‘God and St George!’

Amazingly Drake’s landing near Cartagena under cover of darkness was uncontested – and went unreported by enemy scouts. Carleill’s assault force then formed into columns and marched up the beach towards their objective. Detail of a coloured engraving by Baptista Boazio.

His men stormed the seaward end of the defences, jabbing at the defenders with pikes and swords, firing arquebuses and pistols over the makeshift parapet and hauling the wine casks out of the way to create an opening. There was the briefest of fights along the barricade, and then the attackers flooded through the breach. Some of the English columns attacked the earthworks from the flank, rolling up the defences as they went. The rest charged forward over the open ground behind – now La Marina Park – pursuing the defenders, the bulk of whom were now fleeing into the city. Any remaining defenders were cut down where they stood.

Within minutes Carleill and his men were inside the city itself, pursuing the broken defenders through the darkened streets. Don Pedro Fernandez de Busto was inside the city when the English rushed in, and he beat a hasty exit over the San Francisco bridge, accompanied by the remains of his garrison. Only a few pockets of resistance remained. One Spanish captain, Alonso Bravo, stood his ground in the town marketplace in front of the half-built cathedral, but he was forced to surrender after being wounded several times. His men fled. Another knot of defenders tried to rally in front of the bridge, but they were hopelessly outnumbered. Besides, the English manhandled a captured gun forward, and after a few rounds the defenders retired. By dawn, Cartagena was firmly in English hands.

In this early 17th-century engraving, Cartagena is seen from the south, looking over the defences of the Boquerón Channel towards the Inner Harbour. In the far left distance is the spot where Drake’s men stormed the city’s defences in 1586.

Success on land still left the two galleys defending the Inner Harbour, and Captain Mirabel’s garrison of El Boquerón. Don Pedro Vique was on board the Santiago when the attack began. He immediately drew in to the beach and landed at the head of a troop of cavalry, carried on board as a mobile striking force. He was unable to prevent the rout, and he and his men were forced back to their boats. Meanwhile, after the collapse of the defences, Captain Castaneda of the Santiago tried to support the defenders of the San Francisco bridge by landing troops. Unfortunately, most of his men simply joined the rout, and he was forced to beach his galley under the guns of El Boquerón, and set her on fire. Captain Gonzalez of the Ocasión tried to cross the boom and escape into the Outer Harbour, but panic ensued, and after a fire broke out this second galley was also beached beneath El Boquerón. When Don Pedro Vique appeared there was nothing he could do, so he followed his men to safety on the mainland. It would be pleasing to think that those galley slaves who survived were left behind to be captured by the English. More likely they were escorted ashore, and led back into captivity.

The fort of El Boquerón remained defiant. The defences were well sited, and any attempt to approach the fort was met by a barrage of fire. Drake let it be – after all, he had already captured the handful of ships that remained in the Inner Harbour, and the fort was a hindrance rather than a threat. Captain Pedro Mexia Mirabel and his gallant defenders slipped away the following night, which meant that by dawn on 11 February Drake was the undisputed master of Cartagena des Indies, the greatest city on the Spanish Main.

He established his headquarters in the house of the wounded Alonso Bravo, and gathered his commanders to hear their reports. He would have been amazed by what he heard. Christopher Carleill had lost only 28 men, although at least 50 more had been wounded. Spanish losses were even less – a mere nine men – most of who were slain in defence of the makeshift defence on the beach. It has been argued that if the English had been professional soldiers then they would have been defeated. It was the English soldiers’ ability to improvise their plan of attack as they went along, and their sheer bravado fuelled by religious animosity and a greed for plunder, that carried them to victory. That, of course, and the leadership of Sir Francis Drake.

Then there came the important business of plunder and ransom. Despite Drake’s orders to avoid a looting spree the English soldiers ran amok, ransacking houses and churches until Drake and his officers were able to bring them to heel. Unfortunately for the men, the Spanish had taken all their portable valuables with them before Drake arrived. There was little left to loot. He did capture more than 60 guns, and he immediately ordered his carpenters and gunners to repair their carriages, and to emplace them where they could cover the landward approaches to the city. Drake planned to hold the city until he could negotiate a ransom. He began by demanding ransoms from his prisoners, including his wounded host Alonso Bravo. Drake demanded 5,000 ducats from him to ensure his release, and the sparing of his house and possessions. The two men came to an agreement, and eventually Drake allowed the militia captain to join his wife on the mainland, as she was suffering from fever. When she died Drake allowed her husband to bury her in the city’s Franciscan graveyard, and he even attended the funeral, his men firing a volley over the grave as a mark of respect. Drake eventually waived the ransom, and reduced that of the Franciscan priory to a token 600 ducats.

In February 1586, Sir Francis Drake arrived off Cartagena des Indies, a city known as the ‘Jewel of the Spanish Main’. During the early hours of 10 February Drake landed an assault force on a deserted beach on a sand spit, a few miles south of the city. The English soldiers were commanded by Lieutenant-General Christopher Carleill whose men reached the main Spanish defensive line an hour before dawn. These imposing defences spanned a narrow neck of land, but Carleill noticed that it was low tide, and the beach on the Caribbean side of the sand spit was weakly defended – a mere line of sand-filled barrels. He ordered part of his column to ‘demonstrate’ in front of the main defences, while he led the rest of his troops to the left, towards the shore. When Carleill gave the signal, his assault columns stormed the makeshift barricade. The English outnumbered the defenders, and soon weight of numbers made the difference. When some of the barrels were heaved aside, other soldiers poured through the breach, and within minutes the Spanish defenders were running away, heading into the city, with the English hot on their heels. The fighting only lasted a few ferocious minutes, but with its defences breached and its defenders routed, Cartagena lay at the mercy of Drake and his men.

Formal negotiations began on 15 February. Governor Don Pedro Fernandez was summoned to Drake’s quarters, accompanied by his leading negotiator Father Don Juan de Montalvo, his deputy governor Don Diego Daca, and Tristan de Oribe Salazar, one of the city’s leading merchants. As he had at Santo Domingo, Drake began by demanding a hugely inflated ransom of 400,000 pesos. The Spanish said they were willing to pay up to 25,000. With the negotiations in deadlock, Drake repeated his earlier tactic, and ordered parts of the city to be set on fire. Almost 250 houses were destroyed before the Spanish offered a compromise, and in the end a deal was reached. Drake was offered 107,000 pesos in return for sparing the rest of the city. On top of this, Drake and his men managed to extort all those smaller individual payments, of the kind he had demanded of Alonso Bravo. They amounted to anything up to 250,000 pesos, the majority of which had been gleaned from the Church. He accepted the governor’s offer, and for several days mule trains carrying silver and gold kept appearing in the town marketplace, guarded by Carleill and his soldiers.

During these negotiations Drake was both affable and courteous, although Don Pedro Fernandez found him boastful, and prone to launch into bitter tirades aimed at King Philip and Pope Sixtus V. He also bragged about where he might strike next, threatening to attack Panama or Havana, and defeat any Spanish fleet sent to stop him. Drake was certainly thinking about his next move, and clearly the old dream of capturing Nombre de Dios and Panama wasn’t far from his mind. He knew he could rely on the Cimaroons as allies, and with the force at his disposal he might have just succeeded. However, events were to overtake him, and would prevent any more major assaults.

By the start of March, the fever that had carried off Alonso Bravo’s wife had spread to the city, and during the weeks since its capture more than 100 of Drake’s men had died, including his friend George Bonner, captain of the Bark Bonner. Incidentally, he also lost another old comrade – Tom Moone, captain of the Francis. He had accompanied Drake on his first expedition to the Caribbean, and on his voyage into the Pacific. He and another captain were killed during a skirmish with a small Spanish ship, when it unknowingly sailed into the Outer Harbour. Drake buried his old shipmate in the grounds of Cartagena’s cathedral. As March drew to a close and the ransom negotiations were completed, Drake must have been eager to leave. By that stage more than half his men were sick, and the only hope for the remainder was to escape from the festering swamps and dripping humidity of the Venezuelan coast.

Another motivating factor was Cartagena itself. On 27 February, Drake called a Council of War to decide what to do with the city. It was suggested that Cartagena should be held by the English, and turned into a permanent English settlement in the heart of the Spanish New World. While this notion had its attractions, it would have required a monumental effort on the part of the English crown. A fleet would be needed to guarantee its security and supply, and the drain on the Queen’s resources would be immense. Besides, with fever spreading rapidly it was clear that Cartagena was hopelessly unhealthy. It was decided to abandon the city as soon as the ransom was collected.

By then it was clear that Drake lacked the manpower to launch another major assault against a Spanish city. That meant he had to abandon his notion of marching across the Isthmus of Panama to assault the city on its Pacific coast. His captains promised to follow him wherever he chose to lead them, but the majority clearly wanted to cut their losses and return home. After all, most of them had joined the expedition purely in the hope of earning a fortune in plunder. While Cartagena had been lucrative, the plunder from the expedition fell far short of what everyone had expected. Eventually, Drake decided to cut his expedition short and return to England. However, he hoped to launch one last assault on the way, ideally against the Cuban capital of Havana, which he discovered was still poorly fortified.

Before they left Cartagena, the English took whatever remaining goods they could, which could be sold for a profit somewhere on the voyage home. It was also claimed that he embarked around 500 slaves, but whether these were given their freedom by Drake is still unclear. As he had Cimaroons in his company, it would have been difficult to treat black slaves as a human commodity. The likelihood is that he planned to transport them to a place of safety. He also took whatever guns he could fit into his ships, leaving Cartagena defenceless. While the official plunder was set at 107,000 pesos, the private plunder brought the total to a more respectable total, possibly as much as 357,000 ‘pieces-of-eight’. If we add the value of the guns, church bells and other goods, the total increased to more than 500,000 pesos – a respectable haul indeed, and more than Drake’s windfall when he captured the Nuestra Señora del la Concepción in the Pacific. The only problem was that this time the loot had to be shared between many more people.

Drake finally sailed from the city on 10 April, after spending the best part of two months in Cartagena. Few of his men would have been sad to leave the fever-ridden place. The first attempt to leave was thwarted by a sinking ship. The New Year Gift, captured by Drake at Santo Domingo, had begun taking on water soon after she entered the open sea. Drake turned back to repair her, but eventually abandoned the vessel in the Boca Grande anchorage. The extra day was spent baking ship’s biscuits, and so it was 12 April before Drake finally disappeared over the horizon. He was only just in time. Two days later a Spanish fleet arrived, sent from Seville to trap Drake. They were too late – El Draque had got clean away.

Behind them the Spanish had to explain the debacle to their King. Don Pedro Fernandez de Busto made a brave start. As he put it: ‘I do not know how to begin to tell your Highness of my misfortune… I can only say that it must be God’s punishment for my sins, and for those of others.’ The worst of it was that the bulk of the official ransom had been paid using royal funds. It would take years for the city to repay the treasury, and to recover from the raid. Meanwhile, its defences had to be rebuilt, its buildings repaired and its citizens had to recover from the traumas of assault, disease and financial ruin. Drake would be remembered for decades to come.

10 FEBRUARY 1586

When Drake arrived off Cartagena des Indies, the city governor was expecting him, and deployed his meagre force to good effect. While his dispositions were good, he had to defend the town and the harbour, and guard against attacks from several directions. By contrast, Drake was able to concentrate his assault force, then unleash it at a key point in the Spanish defences. Once again Drake and his fleet did what they could to distract the defenders, while Robert Carleill and his men delivered the winning blow.

KEY

A English fleet (Drake)

B The English assault force (Carleill) – 1,000 men in 18 companies

C The galleys Santiago and Ocasión (Vique y Manrique) – 300 men

D The Spanish Main defensive line (de Busto) – 500 men, including 200 Indians E El Boquerón Fort (Mirabel) – 200 men

|

EVENTS |

1 Late on the evening of 9 February, Drake supervises the landing of Carleill and his men on La Punta del Judío, on the southern end of the sand spit of La Caleta. By 2.00am the landing is complete, and Drake returns to the Elizabeth Bonaventure.

2 Carleill and his men work their way northwards up La Caleta under cover of darkness. They avoid the poisoned stakes planted to bar their way by bypassing them, wading through the Caribbean surf. Amazingly, no Spanish patrols discover the English assault force.

3 Around 4.00am Carleill is in position, a few hundred yards from the entrenchments spanning the narrow northern neck of La Caleta. At that moment his presence is detected, and the Spanish begin firing on his men from their entrenchments. They are soon joined by the Spanish galleys Santiago and Ocasión in the Inner Harbour, and by a battery of heavy guns mounted in the centre of the Spanish earthworks.

4 Carleill spots the weakness in the Spanish defence – the earthworks only cover the solid ground of La Caleta, not the beach on the Caribbean side of the line. It is protected by a makeshift barrier of sand-filled barrels. He orders the bulk of his force to storm this barricade, and after a few minutes of fierce hand-to-hand fighting the English column breaks through.

5 The Spanish flee towards the city, pursued by the English soldiers. Within minutes Carleill and his men clamber over the crumbling city wall and enter Cartagena. His men chase the Spaniards through the streets, and although pockets of resistance form at the main square and the bridge leading from the city, these are soon overcome. Cartagena is now in English hands.

6 Meanwhile Drake’s fleet ‘demonstrates’ in front of the Boquerón Channel. The two galleys are unable to escape, and so their commanders beach them beneath El Boquerón fort, and set them on fire. The fort remains in Spanish hands until the following evening. Apart from this last bastion, the ‘Jewel of the Spanish Main’ falls to Drake.

Drake was still eager to attempt two more things before the expedition finally turned for home. First, he wanted to launch a last attack against a Spanish city, preferably Havana. Second, he planned to visit Walter Raleigh’s new colony in North America before he began his transatlantic crossing, to see whether it would serve as a useful base for future raids. The fleet headed north, and in late April it entered the Yucatan Channel, between the western tip of Cuba and the Yucatan Peninsula on the Central American coast. Drake may have thought about establishing a settlement on the Cuban coast, using some of his black slaves, freed or otherwise, and a group of freed European galley slaves. He even put into the Cuban mainland somewhere near Cape San Antonio, where he helped his men dig wells in search of fresh water, then helped them carry the filled casks back to the waiting boats. The trouble was, once he rounded the corner of Cuba he was met by a strong south-easterly wind, which made it almost impossible to work his way westwards along the Cuban coast towards Havana. After three weeks Drake gave up the attempt, and headed north, up through the Bahamas Channel.

Drake planned to head straight up the coast of Florida to the English colony on the coast of what is now North Carolina. He could disembark his slaves there. The fleet travelled within sight of land, and on 27 May 1586 a lookout spotted a watchtower on the shore, with a small inlet close by. It marked the location of St Augustine, the most northerly town in Spain’s New World Empire, and the oldest permanent colonial settlement in North America. Drake had already heard of the place from a Spanish pilot, but he had no idea where it was. Two decades earlier it had served as a base for Pedro Menéndez de Avilés when he attacked and destroyed the nearby French Huguenot settlement of St Caroline. The Spanish then massacred their French prisoners. It therefore gave Drake one final opportunity to raid and plunder, and a chance to avenge his fellow Protestants.

The small Spanish colony of St Augustine was attacked by Drake in May 1586. In this engraving by Baptista Boazio the English can be seen using small boats to approach and assault the fort and the defenceless settlement beyond it.

Drake sent a landing party to investigate, while Carleill and a few volunteers rowed a ship’s boat into the inlet. The watchtower in the sand dunes was deserted, and there was no sign of any Spaniards. It sat on a strip of sand, separated from the mainland by a band of water, which entered into the inlet. Then they heard the sound of music, a fife. Someone was playing ‘William of Nassau’, a Protestant song. The musician turned out to be Nicholas Bourgoignon, a French Huguenot who had been taken prisoner by the Spanish six years before, and who now worked as an indentured servant. He agreed to guide the English to the Spanish settlement, which lay on the far side of the water, and just round a bend.

Drake and his men occupied the area of the watchtower, and Carleill and his troops prepared themselves for the coming expedition. Everything seemed peaceful until after midnight, when a sentry fired his arquebus. This was followed by shouts and yells, and the sound of more firing. It was an Indian attack, launched by native allies of the Spanish garrison. Drake and his men held their ground, and the relatively open terrain of the sand dunes worked to their advantage, giving them a reasonable field of fire. Within 20 minutes or so the Indians were repulsed, although it seems the attack was never pressed with much vigour.

The following day, Drake, Carleill and around 200 men advanced up the inlet in pinnaces and small boats, and they soon came across a Spanish stockade fort, Fortaleza Juan, built using upright logs. It was deserted. Inside they found a gun platform with 14 bronze artillery pieces, complete with all their equipment; this powerful battery could have inflicted serious damage on the English boats if the fort had been manned. They also found a chest containing the garrison’s pay, about 2,000 gold ducats. What had happened was that Governor Pedro Menéndez Marquez was warned that Drake was off the coast, and he realized that with fewer than 80 militiamen he could offer little in the way of resistance. The garrison and the settlers withdrew inland, leaving Drake to plunder what he could. The chest was probably left behind as an oversight in the rush to quit the settlement. Drake took the guns, and burned the fort to the ground.

A little way beyond the fort the Englishmen came upon St Augustine itself, a forlorn-looking collection of wooden buildings and gardens, capable of housing no more than 300 people. The Spanish were still lingering just beyond the outskirts of the settlement when Drake’s men arrived, and they opened up a skirmishing fire. Anthony Powell, one of Carleill’s two deputies, jumped onto a stray horse and charged the enemy arquebusiers, sword in hand. He was shot from his saddle, then hacked to pieces as he lay wounded. When Carleill and his men arrived, the Spanish melted back into the scrub, leaving Drake in control of the settlement.

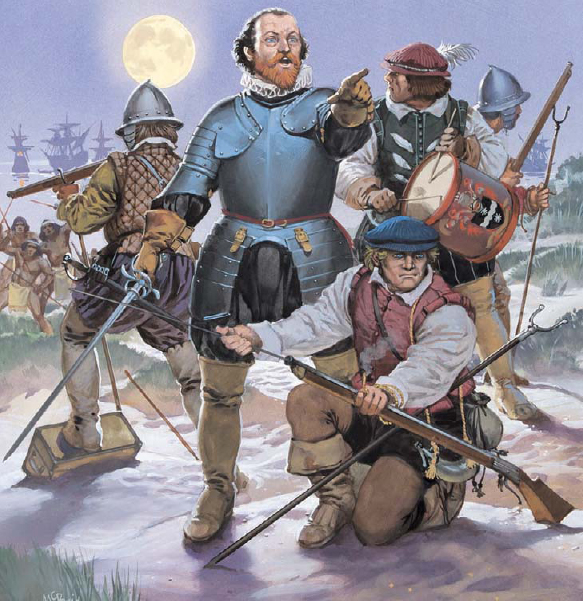

In this stirring painting by the late Angus McBride, Drake is shown rallying his men in the sand dunes outside St Augustine in Florida, when Indians allied to the Spanish launched a surprise night assault on the English camp on the night of 28 May 1586. (Originally in Osprey Elite 70: Elizabethan Sea Dogs.)

The English garrisoned it overnight, then the following morning they collected all tools and implements, anything that would be useful to the settlers, and torched the buildings. Even the orchards and gardens were hacked apart, leaving little of value for the Spanish to return to. Drake’s scouts also reported the presence of a nearby Indian village, presumably the home of the warriors who attacked him on the beach. He decided to ignore it, and after a last cast around for plunder, the English returned to their ships.

As a result of the Great Expedition Sir Francis Drake became one of the best-known figures in Europe. Afterwards he led a preemptive raid on Cadiz, and commanded part of the English fleet during the Spanish Armada campaign of 1588.

The fleet sailed from St Augustine on 29 May, heading northwards up the coast, looking for signs of Raleigh’s settlement. Drake already suspected it lay at a latitude of about 36º North. They looked in to what is now Charleston Harbour, then continued up the coast until they saw smoke. A boat was sent to investigate, and its crew finally made contact with the English settlers, who were encamped on the island of Roanoke, just inside the line of barrier islands now known as the Outer Banks.

It was 9 June. Drake was unable to bring his fleet through the Outer Banks, so he dropped anchor, and accompanied a flotilla of smaller boats as they sailed through the inlet to Roanoke. On the island Drake met Ralph Lane, the governor of the settlement. It was clear that the settlement wasn’t prospering, so Drake made Lane an offer – take passage back to England with him, or remain where he was, in which case Drake would give him whatever supplies he needed. Lane bravely elected to stay where he was, and so Drake’s men ferried provisions and tools from the fleet to the settlement. For the most part Lane’s men were soldiers rather than farmers, and therefore they lacked the skills needed to plant a sustainable crop. Drake did what he could, and left them a small ship – the Francis – and a pinnace which they could use to fish from, together with a handful of volunteer seamen to crew the vessels.

While Drake was busy on Roanoke a storm hit the coast, and the ships had no option but to work their way out to sea, rather than try to ride out the storm at anchor off a lee shore. By the time the storm passed several of the ships had been scattered, including the Sea Dragon, Talbot, White Lion and the Francis – the ship earmarked for the colony. Most of these vessels made their own way back to England.