Was Drake’s great expedition a success? Did it achieve its objectives? One of the problems with arriving at a judgement is that its success was measured by two groups – the investors and the Queen’s policy advisors. To confuse matters further, for the most part these appear to have been the same people. Drake had set out to cause serious damage to Spanish interests in the New World, humiliate Philip II of Spain by demonstrating his inability to defend his realm and divert the annual flow of New World silver and gold from the Spanish treasury to the English coffers. The other objective was to make as much money for his investors as he could, a difficult task given the high cost of fitting out the expedition (placed at around £60,000–70,000) and the substantial number of people who expected to profit from the enterprise. This was the problem with Elizabethan expeditions of this kind: they were joint-stock ventures as well as state-sponsored privateering raids. The two elements – national policy and financial investment – were not necessarily complementary. Drake was therefore torn between hurting the Spanish and turning a profit.

Financially, the expedition was not a great success. The exact value of the plunder Drake brought home is unclear, largely because his accountant died of disease during the voyage, and Drake lacked the clerical abilities to put the books in order before he returned home. We can assume that Drake gained 82,000 pesos from Santo Domingo (a combination of ransom and plunder). A further 357,000 pesos of ransom was extorted from the citizens of Cartagena and the city governor. A meagre 4,000 pesos were recovered from St Augustine, which brings the total haul to 443,000 pesos. That represents the equivalent of 221,500 gold ducats, which were roughly the same as the English pound. Even if we reduce the total slightly due to vagaries in conversion rates, gold or silver quality and the contemporary devaluation of Spanish silver, this still means that Drake’s haul was probably something in the region of £200,000.

On top of that there was the value of the goods taken from Cartagena – the bronze guns, church bells and other portable items. That probably amounted to another 140,000 pesos – the equivalent of £60,000. On Drake’s return a committee was formed, and an audit held. After much deliberation, its chairman Sir William Wynter announced that the total proceeds amounted to just £65,000. Before that, though, those who took part in the expedition were awarded their share of the plunder. We know that Drake applied to the committee for the money he needed to pay off his men. There were also accusations that Drake kept an undue share of the profits for himself, and that the plunder was partially divided long before the fleet arrived back in Plymouth.

The truth, of course, will probably never be known. All the investors, including Queen Elizabeth, received an initial return on their investment of just 75 per cent, which means they made a loss. Drake would have been concerned about this, as given the way these ventures operated, without more financial backers he wouldn’t be able to command any more expeditions. He even waived the right to recoup his own quite considerable costs in fitting out the expedition, which increased the return for his other backers. However, what this official figure doesn’t take into account is the value of the goods that had to be sold, all of which would generate additional income, and which was earmarked for the pockets of the investors. Even if the goods were sold for half their estimated value, that would still generate another £30,000, more than enough to pay off the investors and return them a reasonable but unspectacular profit.

By all estimates, that still left something in the region of £150,000. Most of this would have been earmarked as prize money, to be divided amongst the crew. Although no records survive of Drake’s expedition, we can draw on other contemporary examples to see how prize money was allocated. A set proportion of the plunder – often as much as three-fifths – would be allocated as prize money, and the rest earmarked for the financial backers. We don’t know the exact percentage used to determine the allocation on Drake’s expedition, but around 30–50 per cent would have been normal as prize money. This allocation was fair enough; after all, these were the men who bled and suffered for the money. In some cases, a deduction would be made as recompense to the dead or injured. The allocation on behalf of the 700 or so men who perished during the expedition would be earmarked for their relatives if any had been registered before the fleet sailed, or else returned to the common fund. The wounded often received a bonus, in proportion to the severity of their injuries.

Whatever was left would be divided up amongst the crew. A sliding scale was used, with captains receiving a greater portion than other ship’s officers, and seamen with specific skills earning more than ordinary seamen. For instance, a captain could receive 2 shares, an officer 1½ and a seaman 1. Drake of course would earn the highest proportion of all. It was later claimed that the return for an ordinary soldier or sailor who took part in the expedition was £6. This seems especially low, the equivalent of a year’s wages for an Elizabethan sailor. Even if we set aside larger portions for the dead and bonus payments for the wounded, it still comes to little more than about £20,000.

That still left the best part of £100,000 unaccounted for. While some historians have argued that Drake probably secreted the money away for himself, the truth is he would have found this almost impossible to do. His men had a stake in the profits, and would have been too vigilant. Another possibility – that it was given to the crown as part of a pre-arranged deal – isn’t borne out by the royal accounts, as the money never showed up on the books. Rumours persisted that Drake sent Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, a payment of 50,000 ducats, the rough equivalent of £50,000, but this was never been proven. Then again, at the time Leicester was busy raising an English army to fight alongside the Dutch rebels. This might well have been the kind of secretive payment Elizabeth’s spymaster Francis Walsingham might have arranged.

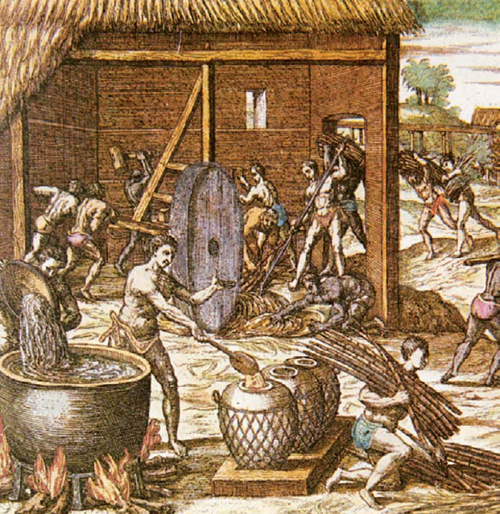

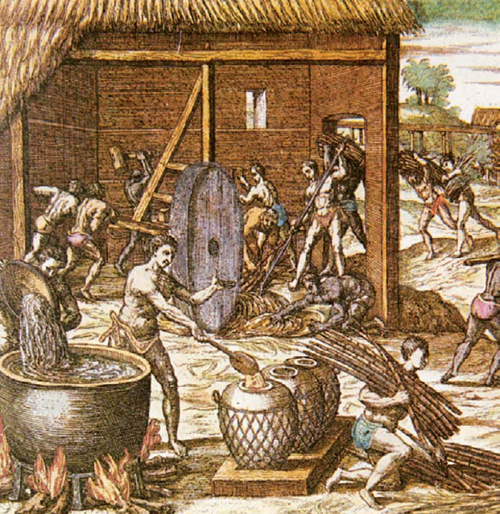

While silver mining was important, the prosperity of Spain’s settlements on the Spanish Main was largely dependent on crop production and slave labour. This late 16th-century depiction of a Spanish sugar plantation was engraved by Theodore de Bry.

Others have pointed out that these men were angrily petitioning Wynter’s committee, demanding their money, which suggests nobody – not even Drake – had received their prize money until a month after the expedition returned home. This situation suggests that there was no initial distribution at sea – a common practice during the period – which would have given the sailors spending money to hand before they reached Plymouth. If this was done then the sums involved were so low that the men spent their extra bounty within days of their arrival, not an impossible feat for a sailor denied the pleasures of home for so long.

Such early payments still wouldn’t have accounted for more than a tiny fraction of the missing £100,000. A more likely explanation is that it never existed, and the estimates of plunder recovered from Cartagena were hopelessly exaggerated. The Spanish themselves claimed that the money and goods taken by Drake and his men were valued at 400,000 pesos. They might well have been exaggerating wildly, in the hope of recompense from the Spanish crown. This interpretation is reinforced by the general impression that the expedition was a financial failure. After all, if Drake had that much plunder left over, a mere quarter of it would have been enough to ensure all the investors revived a profitable return on their investment in the initial division. Unhappy investors meant less chance anyone would put up the money for another expedition. The most likely explanation remains that the haul of plunder was overvalued. Of course, even though this means the expedition was less than successful, there was also that other criterion for success – the political one.

When Drake returned home, one of the first things he did was to write to William Cecil, Lord Burghley. Not only was he one of Drake’s leading backers, but he was also the Lord High Treasurer, and one of Queen Elizabeth’s closest advisors. Drake began by hoping that the voyage would be the foundation for even greater ventures. He continued: ‘My very good Lord, there is now a very wide gap opened, very little to the liking of the King of Spain. God work it all to his glory.’ He meant that he had exposed the greatest weakness of King Philip’s Spain, alluding to the fact that the treasure ports of the Spanish Main lay open to attack. Spanish military and naval power depended on the flow of gold and silver from the New World to Spain. Drake now reckoned that the English could render Spain militarily impotent by intercepting these treasure shipments, capturing Spanish treasure ports and generally destroying Spain’s infrastructure in her overseas empire.

Lord Burghley was well aware that the raid had proved a major humiliation for the Spanish. It was no exaggeration when in a letter to the Queen he declared that ‘Sir Francis Drake is a man fearful to the King of Spain’. He was right. The capture of Santo Domingo and Cartagena – two key cities in the Spanish New World – demonstrated to the international powers just how vulnerable King Philip’s empire actually was. The message was certainly understood by Spain’s creditors – within months of Drake’s return King Philip was turned down for a loan of 500,000 ducats, one supplied jointly by the Papacy and the Florentine banks. The banking house in Seville collapsed as rumours spread throughout Europe that the Spanish couldn’t safeguard their annual shipments of treasure. Even Pope Sixtus V admitted that Drake’s achievements had been impressive. Politically, the raid was a resounding success.

Just as importantly, the Spanish had no idea when and where Drake would strike next. Sir Francis had become one of the most talked-about men in Europe, and in 1586 England had a national hero who seemed capable of achieving anything he wanted. The boost to national morale was incalculable. As the prospects of war loomed ever larger, at least England could count on men like Sir Francis Drake to protect them from the wrath of the Spanish. The irony, of course, is that if anyone helped bring about this war, it was Drake himself, as by now King Philip realized that he could only safeguard his empire by destroying Queen Elizabeth’s England.