one

Why Subscription Works

When I dug into the companies profiled in this book, which vary hugely in what products or services they sell and how they sell them, I noticed that each one has a unique trait, whether it’s an exceptional work culture, a visionary founder/figurehead, or outstanding marketing prowess. Despite these differences, the common thread, which each uses to achieve relationship-driven loyalty from customers, is subscription.

Amazon, Netflix, Spotify, IPSY, and Dollar Shave Club, for instance, recognize that as we enter the next chapter of consumerism, a customer can no longer be just a customer. They must be a loyal follower. A subscriber. A “true fan.”

Subscribers as Fans

In 2008, Kevin Kelly, the founding executive editor of Wired magazine and a former editor/publisher of Whole Earth Review, wrote an essay called “1,000 True Fans.” (Kelly recently rewrote the post, publishing a more succinct version on his website and in Tools of Titans, the 2016 book by Tim Ferriss.) When starting my first business, I referenced the essay. When I started the next business, I referenced the essay. And this year, when I began a set of new personal projects, including a podcast and this book you’re reading, I referenced the essay.

The lessons in it apply to just about anyone wanting to make something of what they create, be it a business, a documentary, a book, a play, or an art project. As Kelly puts it in an introduction to the new version, “the concept will be useful to anyone making things, or making things happen.” The most important principles can be applied to not only individuals, but also to corporations with tens of thousands of people. Each company featured in this book is evidence of the wisdom of the 1,000 true fans concept.

Kelly’s basic premise is that to be a successful creator you don’t need to start with millions of dollars, or acquire millions of customers, clients, or followers. Whether you are a craftsperson, photographer, musician, designer, author, animator, app maker, entrepreneur, or inventor—you only need 1,000 true fans. A true fan is someone who is loyal to your brand, your company, your craft. Someone who will buy anything you produce. These are people who will drive miles to see you sing; buy the hardcover, paperback or audio version of your book; listen to your podcast; purchase the new organic soap you sell from your website. Not only that, they will emphatically share their admiration for your work with their friends, colleagues, and coworkers.

The Long Tail

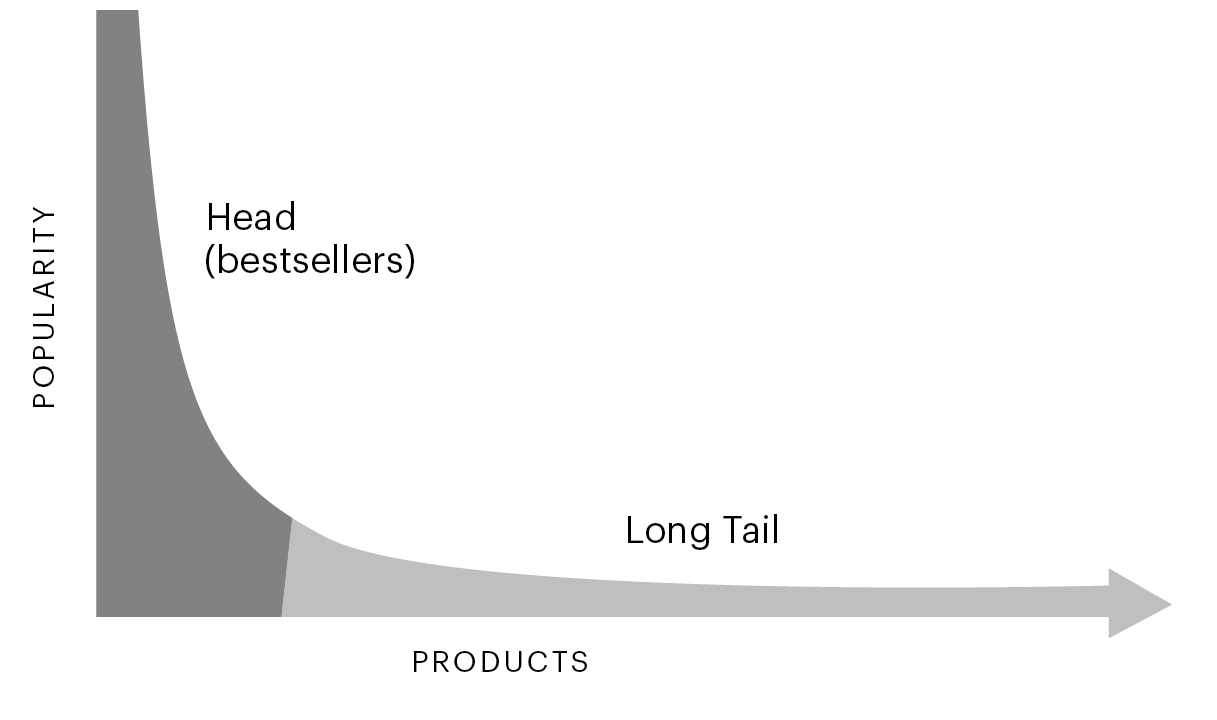

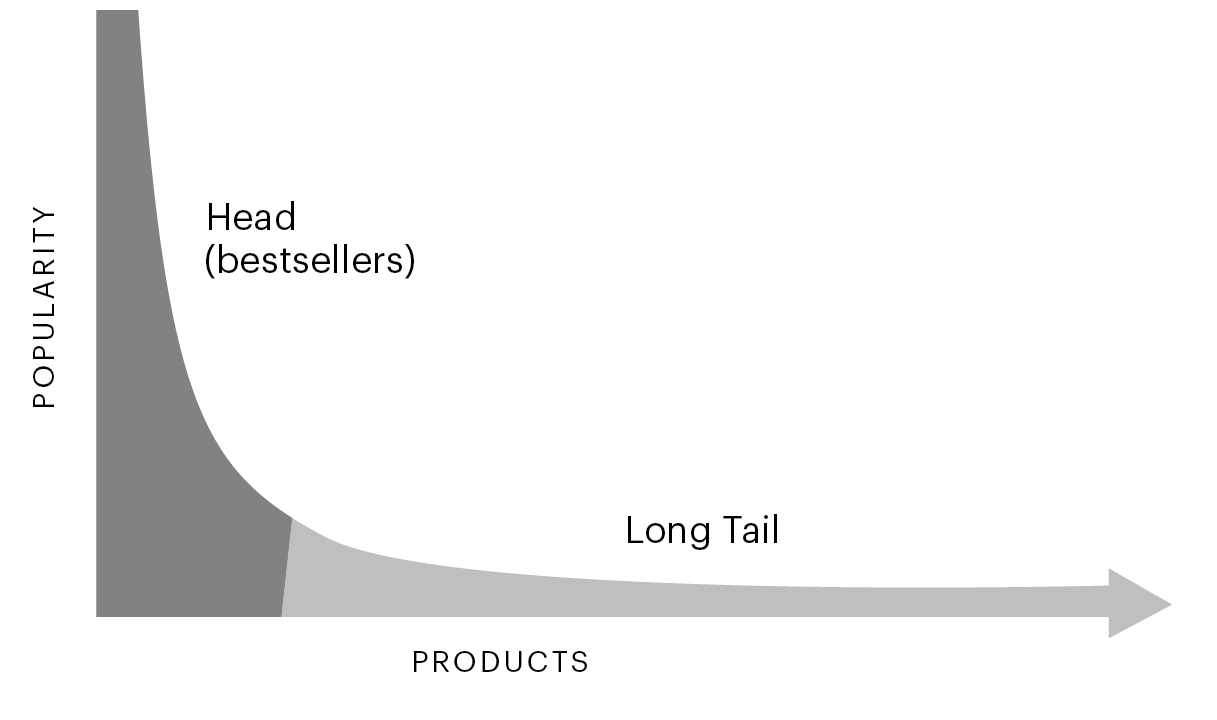

As the internet became thoroughly entwined in most people’s daily lives, it became increasingly easier to find and build an audience —and profit from it. This dynamic was magnified when companies like Amazon and Netflix realized that the combined sales (or views) of the lowest-selling items were equal to, or sometimes more than, those of a few bestsellers. The phenomenon was identified by Chris Anderson (Kelly’s successor at Wired) when he looked at a graph of the average sales distribution curve. He saw “a low, nearly interminable line of items selling only a few copies per year,” which forms a long “tail” on the X axis, as opposed to the “abrupt vertical beast of a few bestsellers” on the Y axis. Anderson’s crucial insight was that the total area of the long tail—i.e., its total sales—was as large as the more celebrated head.

Products in the “long tail” are less popular but more numerous, so the total sales can rival those of the bestsellers. Somewhere in the curve lies the sweet spot of “1,000 True Fans.”

Source: Kevin Kelly, “1,000 True Fans,” The Technium, March 4, 2008, https://kk.org/thetechnium/1000-true-fans/.

And so Amazon and Netflix invented recommendation engines and other algorithms to channel attention to the less popular but more populous creations in the long tail—the titles, products, and content that brick-and-mortar retailers, with their fixed amount of shelf space, tended to shy away from. This meant that any creative pioneer, regardless of how peculiar their product was, now had a channel through which to find an audience.

As Kelly put it, “every thing made, or thought of, can interest at least one person in a million. Any one-in-a-million appeal can find 1,000 true fans.” Knowing they don’t need to worry about securing precious space in traditional marketing and distribution channels, today’s innovators, creators, artists, and entrepreneurs can use social tools like Kickstarter, Facebook, or Instagram to establish deeper connections with their early followers and fans.

The power of the fanbase lies in the multiplier effect. Fans become little marketing organisms that spread brand awareness through word of mouth at dinner parties, family affairs, conferences, networking events, and on social media. They write blogs, post product reviews, share photos on Instagram, and upload videos on YouTube highlighting what they love, and why they love it.

Kelly concludes by proclaiming that “1,000 true fans is an alternative path to success. Instead of trying to reach the narrow and unlikely peaks of platinum bestseller hits, blockbusters, and celebrity status,” he suggests creators aim for a “direct connection” with a more modest number of potential admirers.

You might be wondering what all this talk of “true fans” and the “long tail” has to do with subscription-based businesses. The answer is simple: subscription is a mechanism that lets a brand not only establish an engaged fanbase, but also turn that fanbase into potential profit—fast. As musician Robert Rich pointed out in response to Kelly, it’s tough to make a living from only 1,000 fans if you’re only selling them one album and concert ticket a year. To generate real traction you need to sell them something several times over. Subscriptions are a great way to do just that.

The Problem with Retail

Retail is changing and incumbents are under pressure. So it’s not hard to understand why a focus on customer loyalty is critical. Yet, still, very few companies get it: consumerism is no longer about the transaction; it’s about the relationship. On the surface, this theory might feel opaque. But Kelly neatly underscores this very premise throughout his essay.

Kelly’s theory is just as relevant to a legacy corporation as it is to a solopreneur, but still, we see evidence that big incumbents and their intermediaries aren’t putting this kind of thinking into practice. For big corporations, what typically counts as a “win” is meeting quarterly sales results.

It’s a different era—thanks to digital commerce, consumers have more power than ever before. Consumer-centric direct-to-consumer brands that have seen the paradigm shift are thriving. Legacy players that don’t understand this new relationship-driven economy inevitably falter. This isn’t a prediction. We’ve seen plenty of casualties of this ignorance already, not only with recent bankruptcies like Sears, Nine West, and Claire’s, but also with older, more dramatic deaths that resulted from a failure to evolve: Blockbuster in the face of Netflix, for example, and most of brick-and-mortar retail in its repudiation of the new reality created by Amazon. J.C. Penney, Macy’s, and Toys “R” Us are more examples of brands who’ve taken big swings in the past, but are no longer relevant. J.C. Penney closed 138 stores in 2017 while attempting to restructure its business to meet shifting consumer tastes. Macy’s closed a number of its stores and laid off about 5,000 workers as part of an ongoing effort to streamline. Toys “R” Us filed for bankruptcy in September of 2017 amid mounting debt, joining a parade of other retailers that sought protection the same year, including shoe chain Payless and children’s clothing retailer Gymboree. From 2000 to 2014, over half of the companies listed in the Fortune 500 disappeared, an acceleration that is in large part due to this digital transformation.

While these companies use euphemistic language like “shifting consumer tastes” and “streamlining the business” to explain the shortfalls, the truth is that their transaction-based strategies are being replaced by consumer-centric organizations like Amazon, who build revenue year over year by pursuing deeper relationships with their customer base. As an aside, Amazon now accounts for nearly half of all e-commerce purchases in the U.S., representing $200 billion in revenue or about 4 percent of total U.S. retail. About a third of Americans subscribe to Amazon Prime. Amazon—and others, like Netflix, Spotify, Shopify, and Salesforce—continue to dominate through the relentless pursuit of customer loyalty, using subscription as the foundational business model.

What seems obvious to pioneers like Jeff Bezos (Amazon) and Reed Hastings (Netflix), for instance, is missed by companies that still get caught up chasing quarterly targets. While they pay close attention to cost-cutting and other strategies “du jour” at the board table, the next wave of corporate trailblazers has already shifted—building customer-centric, loyalty-obsessed companies instead.

The Subscription Solution

Since 2012, the number of subscription-box companies has exploded. Pioneers like Dollar Shave Club have leveraged the power of subscription to make shopping online convenient, quick, and perhaps most important, innovative. At the core of their business is a recurring revenue model that attracts healthier business metrics than a traditional online business, while generating increased customer loyalty. According to John Warrillow, author of Built to Sell (2010) and The Automatic Customer (2015), subscription is “the perfect business model because it provides the greatest value to both the entrepreneur and the customer.”

From the entrepreneur’s perspective, that value comes from the guarantee of recurring revenue, which Warrillow describes as one of the most compelling factors in a company’s valuation. Tim Ray, founder of Carnivore Club (a gourmet charcuterie subscription service), agrees, saying he was attracted to the benefit of low-risk recurring revenue. “From a business perspective, it is the most efficient, flexible and easy to operate business model in e-commerce,” he told the Financial Post.

While recurring revenue is attractive, subscription also provides predictive cash flows, better inventory control, and juicy customer lifetime values—all while avoiding the volatility of a typical boom-and-bust product cycle. Most important, subscription creates better customer loyalty by building a relationship between brand and customer. A traditional model means a brand must go to great efforts to re-engage a customer to make a repeat purchase. Subscription, on the other hand, means that that onus shifts from merchant to customer, who, by default, is automatically opted in to repeats unless they sever the relationship by cancelling.

From the customer’s perspective, with any product now available any time via a few clicks, expectations are higher than ever before. Competitors have Amazon to thank for much of this new reality. Even beyond the logistics of the sheer volume of stuff Amazon sells—their largest fulfillment center is over 1.2 million square feet, or 27 acres, and it’s not uncommon for such centers to ship over 1 million items per day— the company has made customer service its focal point since day one. Consider Prime’s one-to-two-day free shipping, which has single-handedly raised the bar for other e-tailers hoping to compete on lead times. Thanks to the typical Amazon experience, consumers now expect all online sellers to offer both free shipping and product that gets to the front door fast.

This new customer expectation paradigm shift is bad news for most of Amazon’s competition. Brands that can’t adapt face steep challenges ahead. Instead of going toe to toe with Amazon, some are finding ways to leverage the beast. Using “Fulfillment by Amazon” (FBA), for example, many online sellers are tapping into Amazon’s fulfillment centers to house inventory, and subsequently pick, pack, and ship online orders for a fee. Others have significantly cut back on in-house marketing and sales resources, choosing simply to use Amazon’s platform as its primary sales channel. While removing marketing as a core function seems counter-intuitive, the result is often a drastic reduction in marketing costs on the P&L, alongside a boost in revenue stemming from the power and reach of Amazon.com.

In thinking through winning strategies in the Amazon age, there’s plenty of talk in the C-suite about pivoting into subscriptions. But to execute, companies must first understand how their consumers are currently shopping, how they intend to shop in the future, and whether a subscription model fits their business objectives. Moreover, they need to quickly identify which items from their product (or service) stack are conducive to subscription, and how they intend to execute marketing, customer acquisition, billing, and last-mile fulfillment. Last mile doesn’t mean just pick, pack, and ship, but a multi-pronged Amazon-like focus on speed of delivery, customer experience, and support throughout the process—all with the goal of building enduring loyalty from subscribers post-purchase.