CHAPTER THREE

Lowlights, Highlights, and a Cast of Characters

MARINERS FANS LEARNED NOT TO EXPECT MUCH from their team in the early years, and the M’s didn’t provide a lot with the hodgepodge of young and old players they threw onto the field. They lost 297 games their first three seasons, and their accomplishments became as much fodder for folklore as anything to brag about.

Take the Mendoza Line. Please take it, Mario Mendoza would say.

Mendoza, a good-fielding, light-hitting shortstop who the Mariners acquired in a trade with the Pirates before the 1979 season, wore the franchise’s first label of futility. As his batting average lingered around the .200 mark that season, it became known as the “Mendoza Line”—that statistical barrier separating a poor hitter from a putrid one.

George Brett of the Royals made the term popular, once saying after he’d scanned the batting averages in the newspaper, “I knew I was off to a bad start when I saw my average listed below the Mendoza Line.”

A couple of Mendoza’s teammates with the Mariners, Tom Paciorek and Bruce Bochte, also are credited with using the term during interviews in 1979, and in later years TV broadcaster Chris Berman brought it into everyone’s living rooms with constant references to the Mendoza Line on ESPN.

Whatever the origin, it’s Mario Mendoza, the former Mariner, who has been stuck with the label since 1979, when he batted .198 in 148 games. He, Steve Jeltz, and Carlos Pena are the only players to have batted less than .200 while playing at least 148 games since then. Jeltz, an infielder with the Phillies, batted .187 in 1988 and Pena, a first baseman with the Rays, batted .197 in 2012.

What’s nearly forgotten about Mario Mendoza is the role he played so skillfully in preventing Brett from batting .400 in 1980. After a slow start to the season, Brett’s average topped .400 on August 17, and he was batting .394 when the Royals began a late-September trip to the West Coast, beginning with three games at Seattle. Easy pickings, right?

Brett stung the ball throughout that series but was robbed of hits several times on spectacular plays by Mendoza. Brett wound up with just two hits in 11 at-bats through three games at the Kingdome, and when he left Seattle the average had fallen to .389. His run at .400 had suffered a big blow, and he said Mendoza was the reason.

“I still think I should have hit .400 that season,” Brett told Jim Street of mlb.com during a 1995 interview. “The reason I didn’t was Mario Mendoza. Mendoza took three hits away from me, all right up the middle, on unbelievable plays. I needed five more hits for .400.

“To this day, I hate the sucker,” Brett added, joking.

Back-to-Back Thrillers

There wasn’t a finer weekend in the early years than a two-day stretch in May 1981, when Tom Paciorek delivered a couple of the sweetest swings in the Mariners’ early history.

Paciorek, a 34-year-old outfielder signed by the Mariners in 1978 after he’d been released by the Braves, started the ’81 season on a hot streak, batting .377 after three weeks. He’d cooled somewhat by the first of May, but still posed an offensive threat.

May 8 and 9, he showed it.

On a Friday night at the Kingdome, he led off the bottom of the ninth inning of a tie game against the Yankees and homered off Rudy May, giving the Mariners a 3–2 victory.

The next night, May 9, the Mariners trailed 5–3 when Paciorek batted in the ninth again with two outs and two runners on base. This time he hammered a pitch from Ron Davis for a three-run homer that gave the Mariners a 6–5 victory and set off a wild celebration among the 51,903 fans.

“Those were games you’ll never forget if you were a fan back then,” play-by-play announcer Dave Niehaus said. “When he hit that home run off Ron Davis, everyone in the Kingdome went crazy.”

Armed with baseball bats given away on Bat Night, the crowd clanged their gifts off the metal bleachers during the game, and they continued to use them in the delirium after Paciorek’s winning homer.

John McDonald, who covered the Mariners for the Everett Herald, had hurried from the press box to the Mariners’ clubhouse to get a few quotes from Paciorek. He and everyone else in the clubhouse were astounded at the rumbling they heard from above.

“Everyone was still in the stands and they were banging their bats on the cement,” McDonald said. “It sounded like the place was coming apart out there, and it wasn’t stopping. Paciorek finally went back out for a curtain call, and that’s what it took before everyone stopped banging those bats.”

But Can They Play in Vegas?

The Mariners suffered through a meager existence in terms of success, although any joy they couldn’t find on the field, they certainly seemed to discover off it. From 1979 to ’83, the Mariners had such fun-loving players as Tom Paciorek, Joe Simpson, Bob Stinson, Larry Andersen and, the master of them all, Bill Caudill.

“We had characters on those early teams, we didn’t have players,” second baseman Julio Cruz said. “We had funny guys. Some were good players who were funny. Others were just funny.”

Bob “Scrap Iron” Stinson was an outspoken veteran catcher obtained from the Royals in the expansion draft, and his candid nature got him in trouble with manager Darrell Johnson right away in 1977. Asked by a newspaper reporter during the team’s first spring training when he thought the fledgling Mariners would be eliminated from the division race, Stinson answered honestly.

“Opening Day,” he said.

Johnson called Stinson into his office and chewed him out for making that statement, but not because Johnson disagreed. He simply didn’t want the Mariners’ fans to hear that kind of negative talk before they had a chance to get their hopes up for the new season.

Later in the season, during a game at Milwaukee, Mariners pitcher Glenn Abbott was getting knocked around in the bottom of the first inning after the M’s had given him a lead. Pitching coach Wes Stock visited the mound and directed his first question at Stinson.

“What kind of stuff does he have?” Stock asked. “I can’t tell you,” Stinson said. “I haven’t caught any of his pitches yet.”

Back in the dugout, Stock relayed those words to Johnson, who was waiting when Stinson came off the field after the inning. He told his catcher that if he wanted to be a comedian, he should try Las Vegas.

Always Room for JELL-O

The ’77 team had its share of fun as the losses—and occasional victories—mounted. “They were just the normal pranks you’d find in any clubhouse,” pitcher Gary Wheelock said. “It was stuff like the three-man lift.”

Otherwise, that first team was fairly benign compared with the hi-jinx of later years. The king of the early pranks was the Mr. JELL-O Mystery of 1982.

Larry Andersen, a right-handed pitcher on the 1981 and ’82 teams, conspired with teammates Richie Zisk and Joe Simpson on a prank against manager Rene Lachemann, who was a character himself. Lachemann, for example, spent several nights in the Mariners clubhouse in the Kingdome, figuring it had everything he needed—cable TV, food, a comfortable couch—even though it exposed him to occasional pranks from his players.

No prank gained as much notoriety as what Andersen, Zisk, and Simpson pulled on Lachemann on a road trip. After the team landed in Chicago, the three players went to a grocery store and bought 16 boxes of cherry JELL-O, then talked traveling secretary Lee Pelekoudas into giving them the key to Lachemann’s hotel room.

They poured several boxes of JELL-O into the toilet, bathtub and sink, then mixed it with a bucket of ice to allow the JELL-O to solidify. That wasn’t all of it. They took every piece of the furniture from the room—beds, mattresses, tables and chairs—and crammed them in the bathroom. Then they removed all the light bulbs from the fixtures, took the mouthpiece from the telephone, unplugged the clock and strung toilet paper around the empty room.

“Anything we could think of, we did,” Andersen said in a 2001 interview with astrosdaily.com, a website covering the Houston Astros, where he played in the late 1980s. “He came back from a night out and poof, his room was no longer a room.”

Lachemann later praised the creativity of the prank, but not before he threatened to call the authorities and have the players fingerprinted and subjected to lie detector tests. Lachemann never followed through to that extent, even though the Mr. JELL-O mystery continued to have twists and turns the next few months.

Play-by-play announcer Dave Niehaus took part in the shenanigans by telling Lachemann that he had gotten a confession on tape from those responsible. The problem, Niehaus told Lachemann, was that he accidentally erased the tape.

Andersen had a fake newspaper page printed with the headline, “Jello-gate tapes lost, Lach baffled.”

“Every place we went the rest of that season, there was JELL-O,” Lachemann said. “I had a meeting after a game one day with my coaches, Dave Duncan and Bill Plummer. We’d usually have a beer when we got together like that. Those two took one drink of their beer and then spit the stuff out. It turned out someone has gotten into our cans of beer and figured a way to pour out all the beer and replace it with JELL-O.

“It was amazing.”

Lachemann had become convinced that an accessory to the crime was outfielder Tom Paciorek, a former fun-loving Mariner who played that year for the White Sox. Because the prank occurred in Chicago, it seemed likely that Paciorek could have been involved. He wasn’t, but when the prank gained national attention and Paciorek’s name was linked with other suspects, his mother called Lachemann to apologize for the actions of her son.

The pranksters didn’t reveal themselves until the Mariners held their season-ending party. Andersen, Simpson, and Zisk appeared with their heads covered by bags that were made to look like JELL-O boxes and taunted Lachemann a final time with a game of “What’s My Line?”

“In all the years I’ve been in the game, that’s the best prank I’ve ever seen,” Lachemann said in 2006. “It was a great, great prank and it went on the whole year.”

Bill Caudill and His Bag of Tricks

Right-handed pitcher Bill Caudill brought legitimacy to the Mariners’ bullpen when he arrived in a trade with the Yankees just before the 1982 season. He also had a Sherlock Holmes cap, a pair of handcuffs, and a zaniness that helped keep the Mariners’ spirits up when the season went south.

The Mariners fielded their first reasonably competitive (remember, that’s a relative term when talking about the early Mariners) team in 1982, and Caudill was a big part of it. Not only did he finish fourth in the American League with 26 saves, he also finished with 21 decisions, going 12–9.

“He threw hard, 98 miles an hour, and when we needed a save, we went to him,” second baseman Julio Cruz said.

The high point was July 8, when Caudill recorded his 17th save in a 4–3 victory over the Orioles at the Kingdome, pulling the Mariners seven games over .500 at 45–38 and leaving them just three games behind first-place Kansas City in the American League West.

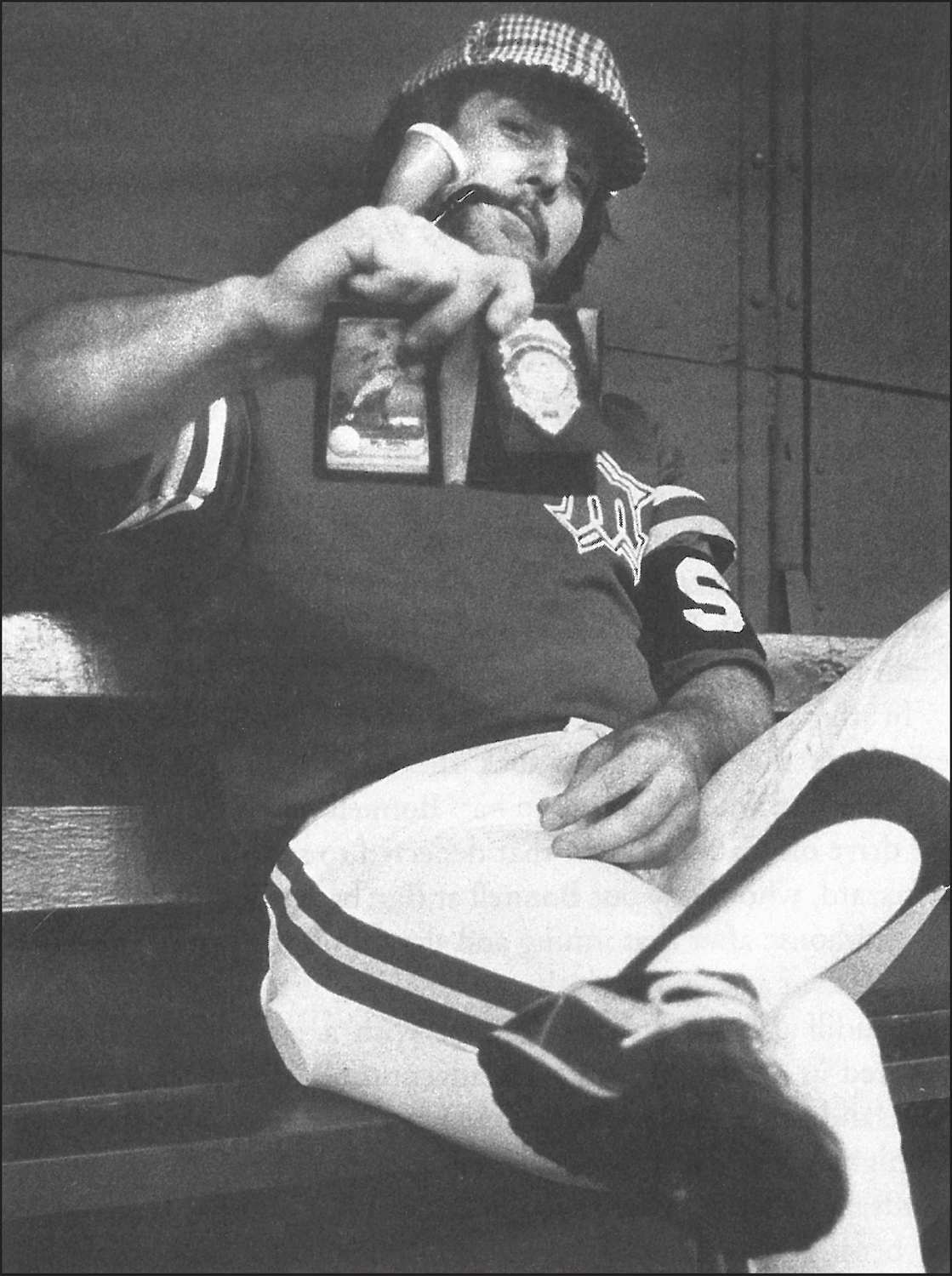

Bill Caudill. Photo courtesy of the Seattle Mariners

“He was great in the clubhouse, but the main thing is that he was an outstanding pitcher,” manager Rene Lachemann said.

Good times on the field, of course, didn’t last. These were the Mariners, after all.

They lost seven of their next eight and fell from contention. As important as Caudill was on the mound during the Mariners’ successes, he played just as big a role, maybe bigger, off the mound when the team needed an emotional boost during hard times.

Caudill was a cutup around the clubhouse, and the only times anything or anyone were truly safe from his antics were when he was on the mound.

It started early in the season after the Mariners had lost seven of their first nine games. Caudill got hold of a Sherlock Holmes-style houndstooth cap and conducted an inspection of the Mariners’ bats as he searched for the missing hits responsible for such a poor start.

Teammates began calling Caudill “The Inspector”—as in Inspector Clouseau of The Pink Panther—and a persona was born.

Dick Kimball, the Kingdome organist, fed Caudill’s new image by playing “The Pink Panther Theme” when he entered games, and the fans got into it. They would send Caudill all sorts of items, and his box of goodies included an inspectors badge, magnifying glasses, a couple of stuffed pink panthers and a Calabash pipe.

Caudill used those props to play pranks on teammates and others brave enough to venture near him before and after games. He also tried some unconventional tricks when everything else failed to shake the Mariners out of their losing ways.

One night, after being called out of the bullpen to pitch a tight game against the Blue Jays in 1983, Caudill appeared with half a beard, talked into it by a teammate, pitcher Roy Thomas.

In the opposing dugout, Barry Bonnell told his Blue Jays teammates that he would knock the other half of the beard off Caudill’s face when he came to bat. Bonnell nearly did, blistering a line drive off Caudill’s chest that deflected to second baseman Tony Bernazard, who threw out Bonnell at first base. Caudill ducked into the clubhouse after that inning and shaved off the rest of the beard, then pitched a scoreless ninth.

Caudill did his greatest damage with a pair of handcuffs he acquired as a memento of a misadventure during a road series in Cleveland. He’d been in the lobby at the team hotel well past midnight after the team had arrived from New York. Security guards, wary of anyone lingering around the hotel at that time of day because of a series of car thefts in the vicinity, stopped Caudill and questioned him. Caudill’s answers apparently didn’t satisfy the security guards, who slapped a pair of handcuffs on him and threatened to call police. Word of the incident got upstairs to Lachemann, who reported to the lobby and talked the guards into letting him deal with Caudill.

Lachemann guided Caudill to his room and the incident was over. Or so he thought.

Mariners designated hitter Richie Zisk made sure the residue of that night remained forever, giving Caudill a pair of handcuffs. Caudill didn’t simply keep them around as a symbol of his episode in Cleveland, he put them to constant use.

When Caudill wasn’t slapping those cuffs on an unsuspecting victim, he had everyone else wary of them. Soon, “The Inspector” acquired a second nickname: “Cuffs.”

Before one game, Caudill had an idea for Lachemann.

“When you call me down in the bullpen, give me the cuffs sign,” Caudill told his manager, holding up his wrists as if they were clasped together.

Later that night, when Lachemann needed Caudill to warm up, he flashed the “cuffs” sign. Caudill got loose and Lachemann brought him into the game.

“Then he gave up a three-run homer and blew the save,” Lachemann said. “We put that ‘cuffs’ sign on the back burner after that.”

The handcuffs became a common sight at the ballpark, home and away.

“He always had them with him, and he would walk up to you and just slap them on you,” Cruz said. “Or he would come up and say, ‘Let me see if these will fit,’ and cuff you, and then walk away. That’s how he got the owner’s wife.”

Judie Argyros, wife of owner George Argyros, was in the Mariners dugout before a game at the Kingdome when Caudill demonstrated his handcuffs. He clasped one cuff on her wrist, the other to the dugout bench, and walked away. She remained stranded while players warmed up for the game, while the grounds crew prepared the field and while everyone else stood at attention during the national anthem.

Just before the first pitch, Caudill freed her.

Caudill never got those cuffs onto George Argyros, although he did pull a good one on the owner during contract negotiations with the Mariners. Caudill was represented by a budding young agent named Scott Boras, who was Caudill’s roommate when they played minor-league baseball together. Boras got Argyros to agree on a contract clause that allowed Caudill to throw a dozen balls into the crowd at each game.

That was no small feat back then, because Argyros maintained strict control of expenses. He would station an employee in the press box to monitor players who threw baseballs into the crowd, and those who did would have the price of the balls deducted from their pay. All except Caudill, that is.

Larry Andersen, a pitcher on the 1981 and ’82 teams, often was a partner in Caudill’s playfulness. Andersen had a Conehead mask—made famous by the old Saturday Night Live characters—that he kept throughout his major-league travels, and Caudill plucked it from his locker during a rain delay in Detroit. He pulled the Conehead over his head, stuffed his jersey so it was nice and plump, then entertained the crowd with an animated parody of fellow pitcher Gaylord Perry, complete with a mimicking of Perry’s reputed doctoring of the baseball.

Perry was so agitated he tried to tear off the cone … with Caudill’s head still in it.