CHAPTER FIVE

When All Else Fails, Give Something Away

SEATTLE HAS LONG EMBRACED BIG EVENTS.

The annual unlimited hydroplane boat races would draw hundreds of thousands to Lake Washington. The NCAA played its Final Four in the Kingdome three times, bringing big crowds and Chamber of Commerce notoriety to the city. University of Washington football games drew tailgating crowds to Husky Stadium a half-dozen Saturdays each fall, and the NFL Seahawks filled the Kingdome on Sundays. Even the Mariners made a splash when they hosted the All-Star Game in 1979.

The Mariners’ big challenge, however, was trying to sell the everyday concept of baseball.

Opening Day sold out annually, but that was never a true gauge of the interest in baseball. The Mariners’ first opening night in 1977 drew 57,762 to the Kingdome; their second game drew 10,144. They drew more than 1.3 million in the first season when the return of baseball became somewhat fashionable, but they didn’t come close to breaking one million the next four years.

“In those early years we learned that it was an event town,” said Randy Adamack, then the Mariners’ public relations director. “Opening Day for us is a big event, and at certain times during the year a Mariners game would have a big focus. Our challenge was that we played 81 times here and we needed to make each one of them an event.”

To do that, they did what all good promoters would do when their product alone wasn’t enough to fill the seats. They gave stuff away.

The Mariners had hat nights. They had bat nights. They gave away T-shirts and jackets. They also brought in entertainment, some of it good, some lousy, to entice folks into spending beautiful summer Saturday nights inside the concrete dome.

Some of those promotions were big hits, some were flops, and many became part of the Mariners’ lore.

Face of the Franchise: Funny Nose Glasses

The Mariners gave jackets to fans during one promotion in 1981, and to publicize the event they put together a TV commercial starring outfielder Tom Paciorek.

His sales pitch: “Hi everybody, I’m Tom Paciorek of the Seattle Mariners. This Saturday night, come to the Kingdome because the first 30,000 fans will receive a pair of these great funny nose glasses. That’s right, funny nose glasses.”

Paciorek put on a pair of the glasses, featuring a big bulb of a nose and a black mustache, when a voice from behind the camera interrupted.

“No Tom, it’s not Funny Nose Glasses Night, it’s Jacket Night. The first 30,000 will get a Mariners jacket.”

Paciorek looked stunned. “Then what am I supposed to do with 30,000 pairs of funny nose glasses?” he asked.

“Tom,” the voice added, “that’s your problem.”

Jacket Night went over well, as most Saturday night giveaways did, but the commercial starring Paciorek left fans with a taste for more, specifically noses and glasses. The Mariners were besieged with calls from fans wanting a Funny Nose Glasses Night. In 1982, those fans got their wish.

The Mariners scheduled the promotion for May 8 and the response was overwhelming. A crowd of 36,716 showed up, almost 10,000 more than two nights earlier when Gaylord Perry beat the Yankees for his 300th career victory.

Men, women, and children wore their funny nose glasses in the stands, owner George Argyros and his wife, Judie, wore them, as did the Mariners themselves. The relief pitchers walked to the bullpen before the game wearing them, all looking like the sons of one really ugly daddy, and manager Rene Lachemann wore a pair to home plate for the pregame meeting with umpires.

Plate umpire Tom Haller took one look at Lachemann and said, “No wonder you guys are in last place.”

Hold the Smoke

Randy Adamack had flown into Seattle on July 5, 1978, the day before he began his new job as the Mariners’ public relations director. After he got settled in his hotel room, he opened the sports section to get a feel for what was going on with the Mariners.

“There was a story at the bottom of the page saying how the laser light show scheduled for July 4 had been smoked out,” he said. Intrigued, he read on.

Immediately after the Mariners lost 5–3 to the A’s, the crew responsible for the postgame Fourth of July laser show began setting up its equipment behind second base, in the middle of the Kingdome field. Part of the look was to pump enough smoke into the dome for the lasers to have a cool effect.

“The problem is that they put out about 10 times more smoke into the building than they should have,” Adamack said. “The whole place was filled with smoke and they had to evacuate the building. By the time the smoke cleared about an hour and a half later, there wasn’t anybody left to see the show.”

It did go on, however.

“A handful of people from the staff were still hanging around,” Adamack said, “and they said it was a heck of a laser light show.”

Mascot Maniacs

The San Diego Chicken had become a phenomenal success in the late 1970s, and the Mariners decided to catch that wave 1981. Not just by having the Chicken show up at their ballpark, but by staging a mascot contest.

They called it the International Mascot Competition and invited anyone interested in being considered as a mascot for the Mariners to come to the Kingdome and perform before a game. More than two dozen showed up.

There was a circus performer from Bulgaria who wore a rabbit costume and called himself the “Bulgarian Rabbit.” One guy followed a classic Northwest motif and was a roller skating salmon. Another wore a white suit, and from the waist up he had concocted a replica of the Seattle Space Needle that was about 10 feet tall.

Then there was a guy who called himself “The Baby.” He wore a crewcut, crooked glasses, a diaper that covered just the right places, and nothing else.

Adamack was one of two Mariners employees who served as judges, along with Seattle Post-Intelligencer sportswriter J. Michael Kenyon.

“We introduced the mascots individually and they would come out of the left-field gate and make their way across the field, past third base and over to foul territory in front of our dugout,” Adamack said. “Then they would wave, do flips, rollerskate, whatever it took to impress the crowd and the judges.”

Staying in character, The Baby crawled the entire way on his hands and knees, a distance of about 100 yards over the abrasive artificial turf of the Kingdome.

“When he got to the dugout, he stood up to wave at the crowd, and his hands and his knees were blood red,” Adamack said. “He had worn them raw crawling across the field.”

One judge voted for the Space Needle and Kenyon favored The Baby. Adamack was mulling his deciding vote when Kenyon leaned over and said, “I’m going to rip you guys in the newspaper if you don’t pick The Baby.”

Adamack couldn’t be swayed. He picked the Space Needle.

“J. Michael didn’t talk to me for about a month,” Adamack said.

“I don’t think that promotion drew an extra fan that night,” he added. “But around town it created some talk. It was something that was written about and it was very visual for TV. Our games were on TV only about 20 times all season, and in 1981 we were just happy to have anyone mention our name.”

Buhner Buzz: A Cut Above

The crowning glory of the Mariners’ promotions, at least in the post-Funny Nose Glasses era, was Buhner Buzz Night. Anyone who showed up bald like Mariners right fielder Jay Buhner got into the game free. For those who didn’t arrive hairless, employees from a chain of salons were outside the ballpark with their clippers buzzing, shearing Buhner fans bald in exchange for donations to support breast cancer research.

Seven Buhner Buzz Nights drew 22,302, among them 298 women.

The idea for the promotion sprang in the early 1990s from an on-the-air jab at Buhner’s shrinking hairline by Yankees announcer Phil Rizzuto.

“That’s a summer haircut,” Rizzuto said, pointing out the horseshoe of hair that remained on Buhner’s balding noggin. “Summer good and summer bad. That one’s really bad.”

The Mariners’ marketing staff saw that and, during a brainstorm meeting, came up with the Buhner Buzz Night idea. The first one in 1994 drew 512, including two women, who sat in a special bald-only section in the Kingdome behind Buhner’s position in right field. The Mariners considered it a success, although that head count was nothing compared with future Buzz Nights.

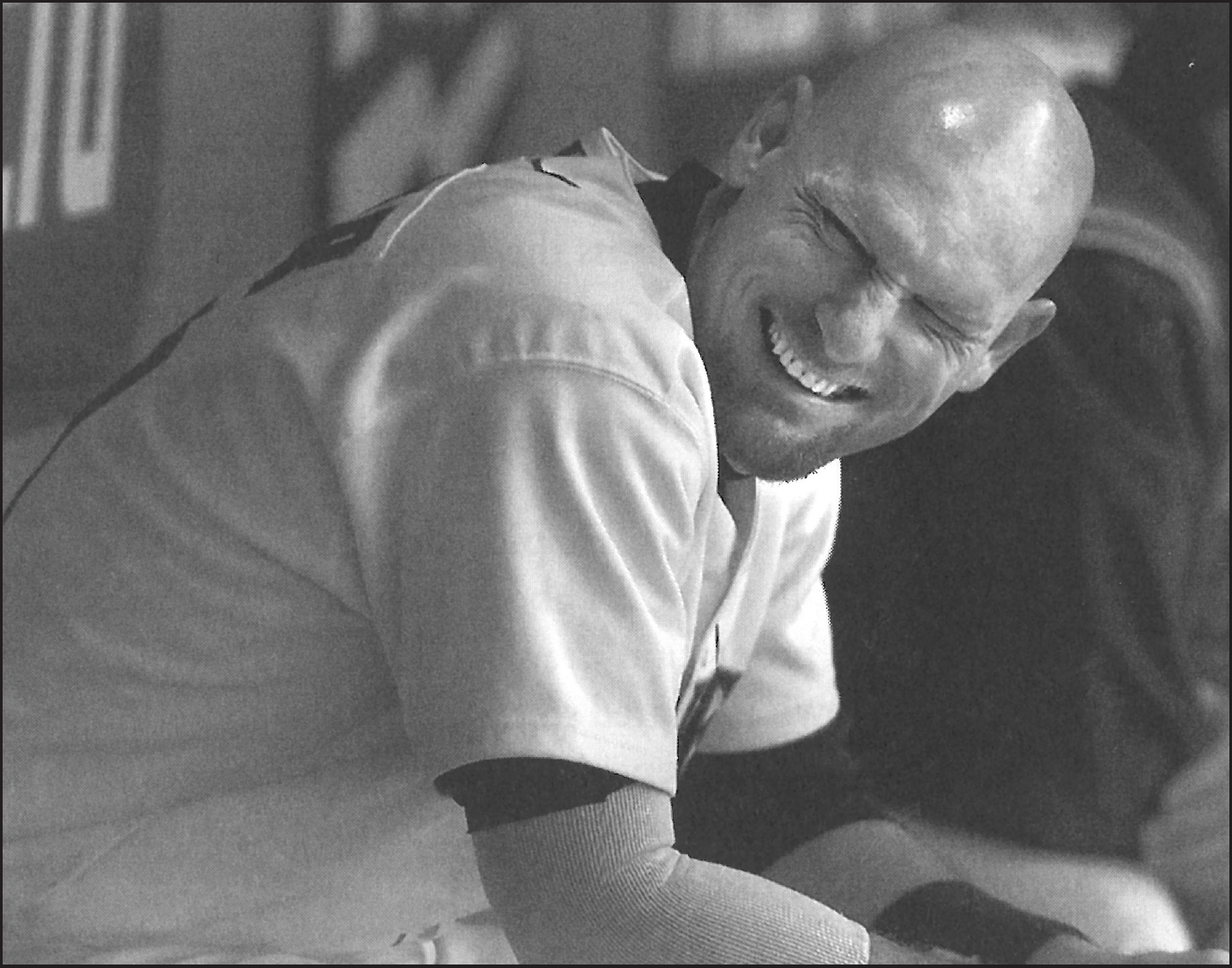

Jay Buhner is all smiles in the dugout. Photo by Justin Best/The Herald of Everett, Washington

In 2001, when the final Buzz Night was held one year after Buhner retired, 6,246 participated, including 112 women. Among them was 77-year-old Helyn Nelson, who auctioned off her hair and raised $148 for a group of students at her church to participate in a mission to Fiji.

At every Buzz Night, Buhner would take a break from his pregame duties to join fans at the buzz-cut stations outside the Kingdome—and at Safeco Field for the final one. He often grabbed a pair of clippers and buzzed away himself. Among his clients one year were his two sons, Gunnar and Chase.

The Mariners also flew Buhner’s father to Seattle from Texas to surprise his son during one Buzz Night. When Jay came outside to mingle with his fans, Dad was sitting in a barber’s chair.

The two embraced, then Jay shaved his dad bald, too.

Class Actors

Nobody would confuse ballplayers with comedic actors, but the Mariners became known since the mid-1990s for the funny commercials that aired each year as part of their ticket sales campaign.

“The team had some modest success in 1993 and we realized that we had some personalities here,” said Kevin Martinez, the club’s marketing director. “This was kind of uncharted waters because we had never used players as actors. But we really felt like there was a need to foster the bond between the players and the fans. Those of us who are around them every day get to see their sense of humor, and the question we asked was how to bring it out.”

The answer, for a series of commercials produced in 1994, was to feature manager Lou Piniella as an impatient psychiatrist, pitcher Randy Johnson as a sometimes-wild circus knife thrower, outfielder Jay Buhner as a bombing standup comedian, and pitcher Chris Bosio as an aggressive dentist.

“That first year,” Martinez said, “there was a lot of skepticism among the players.”

Bosio, for example, wasn’t keen on the first idea thrown to him. The Mariners had wanted the beefy pitcher to dress as a ballerina. He listened to that concept in a meeting with producers, then took the board of sketches and broke it over his knee.

“Guys,” Bosio said, “I’m here to help, but I’m not going to be a ballerina.”

Producers and the marketing staff regrouped and, the next day, presented a new idea: Bosio as a mean, nasty dentist staring down the throat of a frightened patient, much the way he did with hitters from the mound. He loved it and so did the viewing public. Most of them, at least.

“We got complaints from a lot of dentists,” Martinez said.

Buhner’s first commercial featured him as an uninspiring standup comedian whose jokes fall flat in a quiet nightclub. “Here’s one for you,” he began. “Horse walks into a bar. Bartender says, ‘Why the long face?’”

The nightclub audience didn’t stir, so Buhner went to another joke that also didn’t work: “Here’s one for you … ”

Years later, during a ceremony at Safeco Field to honor Buhner after his retirement, he began his speech with, “Here’s one for you …”

Piniella, the fiery manager known for his intolerance for losing and impatience with soft players, became the perfect man to play a psychiatrist. That commercial began with the camera focused on an office door labeled “Dr. Piniella, Psychiatrist.” Behind it was the shadow of a hulking figure who had a patient on the couch.

“Whine, whine, whine!” shouted the voice behind the door, obviously Piniella’s. “All you do is come in here and whine! Now get off your duff and stop acting like a loser!”

The next scene shows the door opening and Piniella sticking out his head, saying, “Next!”

Johnson, known in the mid-1990s for his blazing fastball and occasional lack of control with it, portrayed a circus knife thrower whose skill drew cheers from the crowd as he “threw” knives toward a pretty young assistant.

The camera remained on Johnson as he made a final throw, and all viewers could hear was a huge gasp by the circus crowd. Johnson, who obviously had missed his spot, shrugged as if to say, “Oh, well, stuff happens.”

“A couple of upset people called because they thought Randy killed the girl,” Martinez said.

The commercials became as popular with the Mariners as they were with viewers, and despite long sessions in front of the camera, the players rarely complained and nobody became so impatient that they walked out of a taping. One came close, though.

Joey Cora and Alex Rodriguez were taping one commercial that would show what happens on the team plane during a long flight between cities. The kicker to the commercial was a scene showing Cora and Rodriguez being entertained by a puppet show.

“After they did their lines, Joey and Alex had to sit there as we did this silly puppet show,” Martinez said. “It was taking quite a while to get things right, and the director said, ‘Were going to need a couple more takes.’”

Cora, tired of waiting, looked at Martinez and said, “It’s time to go, bro.”

“Joey had had enough of the puppet show,” Martinez said. “We got two more takes and that was it.”