CHAPTER EIGHT

Bizarre Moments On and Off the Field

SINCE THE FIRST TEAM IN 1977, the Mariners have brought an assortment of interesting behavior by players and incidents off the field, some worth laughing about now and others that still make people cringe.

Bob Kearney was a light-hitting catcher who played eight seasons in the majors, the last four with the Mariners from 1984 to ’87. He was an adequate backstop who was nicknamed “Sarge” and is remembered as much for what he said as the things he did.

“He was really smart IQ-wise, very intelligent. But he also was very, very funny,” said longtime head athletic trainer Rick Griffin, who compiled a list of “Kearney-isms” during the catcher’s time with the Mariners. “He would say things that would make you shake your head.”

Former manager Chuck Cottier remembers the day Kearney replaced his eyeglasses with a pair of contact lenses.

“He’d been trying different types of lenses—hard, soft, whatever—trying to find a pair that worked for him,” Cottier said. “We were playing a Sunday afternoon game in Milwaukee and Bob comes up to me and says, ‘Chuck, I’ve got my contacts now and they’re the best I’ve ever had.’”

Kearney, who’d caught the night before, didn’t start that afternoon’s game, but Cottier had him warm up the pitchers in the bullpen to get accustomed to the new lenses in daylight. Late in the game, Cottier plugged Kearney into the lineup for defensive reasons.

Kearney was behind the plate when Mariners reliever Ed Vande Berg gave up a high popup with runners on second and third base and two outs.

“Sarge circled around it but he didn’t come near it,” Cottier said. “Vande Berg had to catch it off his shoetops for the third out.”

Kearney trotted back to the dugout, looked at Cottier and delivered one of his famed Kearney-isms.

“Skip,” he said. “That sun looks a lot brighter in the daytime than it is at night.”

Mariners president Chuck Armstrong was at spring training one March in Tempe, Arizona, when he decided to strike up a conversation with Kearney.

“Where are you staying down here?” Armstrong asked.

“I’m living in this condo, right on the ground floor,” Kearney said. “It’s great because it’s so warm here at night and I can walk right outside to work on my tan.”

Armstrong was stumped. “You’re working on your tan? At night?”

“Yeah, the moonrays are perfect for that,” Kearney said. “Moonrays?” Armstrong asked.

“Yeah, there’s a full moon now,” Kearney explained. “The rays from the sun are bouncing off the moon, and I get a tan.”

Talented, Unpredictable Rey Quinones

The Mariners thought they were upgrading themselves at shortstop in 1986 when general manager Dick Balderson obtained highly regarded shortstop Rey Quinones from the Red Sox. In exchange, the Mariners traded away solid little shortstop Spike Owen and talented young outfielder Dave Henderson.

The trade left the Mariners with one of the more disappointing players in franchise history. Quinones had remarkable talent but his inconsistent behavior on and off the field wound up hurting the Mariners and himself.

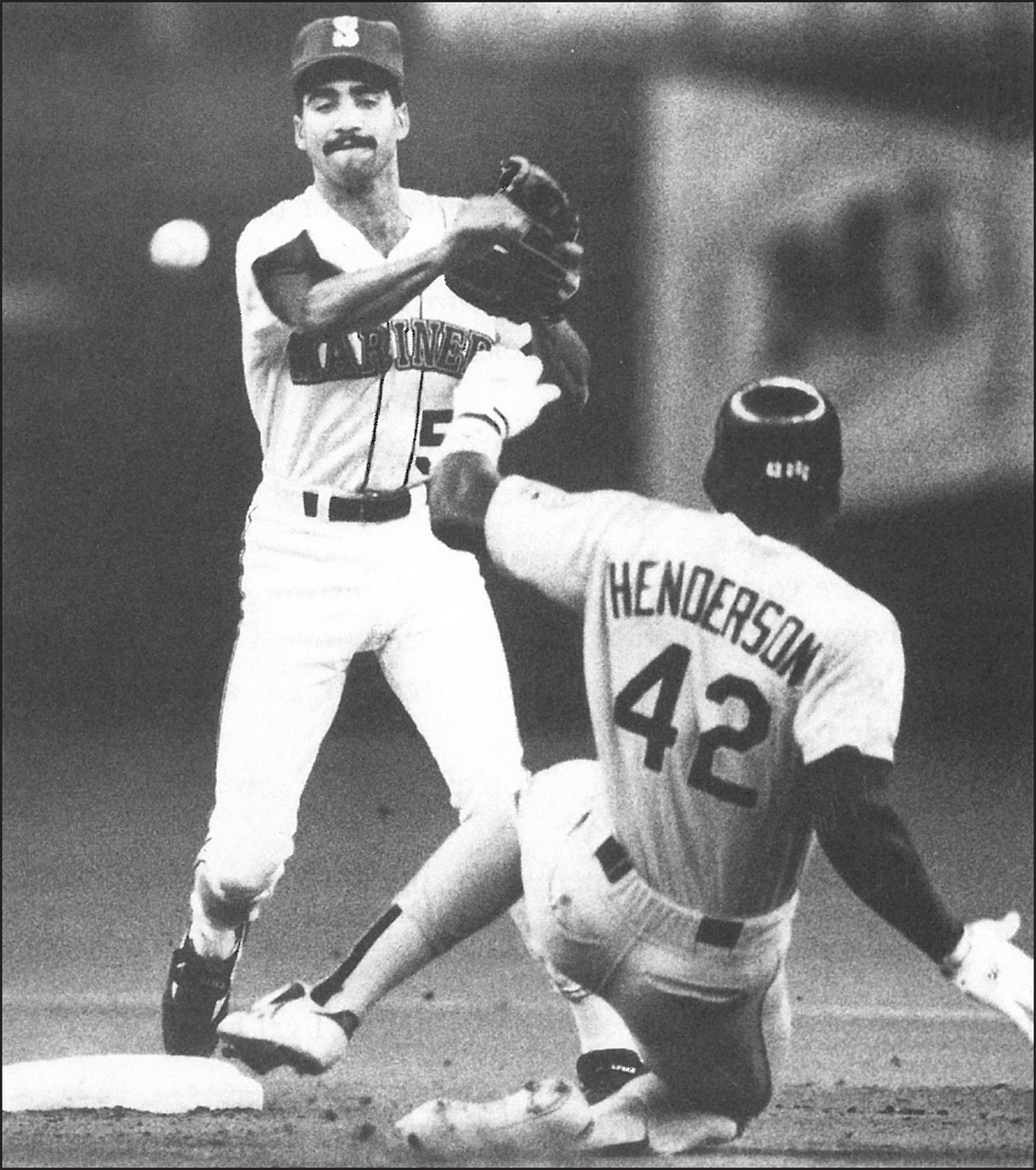

Rey Quinones. Photo by The Herald of Everett, Washington

“To this day, I think he is one of the most talented guys I’ve ever seen,” head athletic trainer Rick Griffin said. “But he didn’t really care about playing the game. He enjoyed being there, but he didn’t want to play.”

Quinones played only four seasons in the major leagues, including 311 games with the Mariners from 1986 to ’89 before they traded him to the Pittsburgh Pirates. The Pirates released him midway through the 1989 season and he never played in the majors again.

How talented was Quinones?

Griffin remembers two games, one in Detroit and one in New York, when Quinones announced in the dugout, “This game is over, I’m going to hit a home run.” Then he went to the plate and did it.

Defensively, Quinones was one of the game’s best talents.

“He could stand at home plate in the Kingdome and throw the ball into the second deck in center field,” Griffin said. “He had the best arm of an infielder that I’ve ever seen. It’s a sad deal. You always wondered what kind of a player he could have been, but he just didn’t have his priorities in order.”

Despite all that talent, Quinones never showed a burning desire to play. He showed up late for spring training in 1987, telling the Mariners he had visa problems.

“Uh, Rey,” team president Chuck Armstrong told him, “you’re from Puerto Rico. You don’t need a visa.”

The writers who covered the Mariners that year won’t forget the day Quinones arrived.

“We got a call one night that Rey was back in the fold, and that we could come up to talk with him,” said Larry LaRue of The News Tribune of Tacoma.

LaRue, Jim Street of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and Bob Finnigan of the Seattle Times went up to public relations director Dave Aust’s hotel suite. They experienced one of the strangest interviews of their careers.

“Rey was lying on his back, flat on the floor the whole time,” LaRue said. “We conducted the interview that way, the three of us and Aust standing above him.”

Among other things, Quinones told the writers that he didn’t need baseball, saying he owned a liquor store in Puerto Rico and could live off that.

Later that season, Armstrong was walking through the Mariners’ clubhouse before a game when manager Dick Williams called him into his office. Armstrong walked in and saw Quinones there with Williams and general manager Dick Balderson.

“Rey, tell Chuck what you just told us,” Williams said.

“I’m a good shortstop, right?” Quinones said.

“You’re a very good shortstop, Rey,” Armstrong told him.

“I could be the best shortstop in the American League,” Quinones said.

“Yes you could,” Armstrong replied.

“I’m so good,” Quinones said, “that I don’t need to play every day.”

Armstrong was stunned as Quinones continued.

“I don’t need to play every day, and you have other guys who should play so they can get better,” Quinones said. “So I don’t need to play tonight.”

Williams reworked the lineup, replacing Quinones at shortstop with Domingo Ramos.

“Rey wasn’t even in the dugout during the early part of the game, Ramos was having a great game,” Armstrong said. “He made a couple of great plays in the field, and he tripled and doubled.”

Seeing that, Quinones put on his uniform and appeared in the dugout, telling Williams that he was ready to play.

“No you’re not,” Williams told him. “You’re out of uniform. No hat.”

Quinones returned to the clubhouse for a hat, then reported to Williams again. Williams told him to take a seat, that Ramos would play the rest of the game.

Other players on the team began calling Quinones “Wally Pipp,” and he had only one question.

“Who’s Wally Pipp?” he asked.

Most Disappointing Manager

The Mariners wallowed near last place in the 1980 season when the club fired Darrell Johnson, their manager since the franchise began in 1977, and replaced him with a man they hoped would take the club in a new direction.

Former Dodgers speedster Maury Wills became the second Mariners manager, and the front office saw him as a person who would instill the up-tempo style that made him such a great player. Besides that, Wills could engage the fans with his entertaining stories.

Unknown to the Mariners at the time, alcohol and drugs were taking a firm grip on Wills. Whether it was the addiction or his inexperience as a manager, Wills was unprepared and overmatched as a manager, and his time was marked by several unusual incidents.

“He probably was the most disappointing manager in our history,” broadcaster Dave Niehaus said. “He came with the reputation of being a baseball guy, but little did we know what he was going through. Some of the things he did were just unbelievable.”

During one spring-training game in 1981, Wills went to the mound to make a pitching change and signaled for a right-hander. There wasn’t a right-hander warming up.

Later that spring, Wills sent catcher Brad Gulden to pinch-hit against a left-handed pitcher, even though Gulden was a left-handed hitter. After the at-bat, Wills was irate.

“Why didn’t you tell me you were left-handed?” he asked Gulden.

Niehaus remembered asking Wills about his outfielders going into the 1981 spring camp, and the answer surprised him.

“We’ve got that guy in left field who’s going to be a pretty good ballplayer,” Wills said. “He had a pretty good year last year and he’s going to be the backbone of our outfield.”

Niehaus, puzzled, asked, “You mean Leon Roberts?”

“Yeah, Leon Roberts,” Wills said.

Roberts wasn’t even with the Mariners, having been traded two months earlier to the Texas Rangers in an 11-player deal.

The most often-told story involving Wills and the Mariners occurred on April 25, 1981, during a series at the Kingdome against the Oakland A’s. Oakland manager Billy Martin had complained during the series opener that the Mariners’ Tom Paciorek was striding out of the batter’s box when he hit the ball and should have been called out.

The Mariners faced A’s breaking ball specialist Rick Langford the next night, and Wills thought he had the perfect solution for Paciorek. He ordered Wilber Loo, the head groundskeeper at the Kingdome, to extend the batter’s box several inches toward the mound. That way, Paciorek would have plenty of room to cheat up and hack at Langford’s pitches before they broke.

“I remember looking at the box thinking, ‘There’s something wrong with that,’” said Randy Adamack, the Mariners’ public relations director. “Then I looked down and Billy Martin was pointing to it and talking with the umpires about it.”

Umpire Bill Kunkel measured the batter’s box and, sure enough, it was a foot longer than the regulation six feet.

Wills was fined $500 by the American League and suspended for two games. Less than two weeks later, the last-place Mariners fired Wills and replaced him with Rene Lachemann.

Not everyone was happy to see Wills leave. Julio Cruz, a young infielder with great speed, became one of the league’s best base-stealers under him.

“He was really good for me,” Cruz said. “I had never stolen a base off a lefty, but Maury would bring me out early and teach me how to do it. I wish he had stayed longer. What he did, he did to himself, and I didn’t pay that much attention to those things. But I know he had a lot to give to the game.”

He Wasn’t a Football Hero

The Mariners sought some left-handed punch for their lineup in 2000, and they obtained outfielder Al Martin from the Padres in a trade-deadline deal. What the Mariners got was a ballplayer who had plenty of controversy swirling off the field.

The Mariners already knew about a bigamy incident involving Martin, who was arrested early in 2000 on charges that he and a woman claiming to be his wife had gotten into a fight. The woman, Shawn Haggerty-Martin, claimed they were married in 1998 in Las Vegas. Martin didn’t deny that he attended a wedding with her, but he didn’t realize the ceremony was real. All the while, he was married to another woman.

The two-wives-at-once episode wasn’t all that raised eyebrows.

Martin had long contended that he played football at the University of Southern California. Media guides with the Pirates, Padres, and Mariners included information—provided by Martin—saying he played at USC. During interviews, he would tell stories of making tackles in big games for the Trojans.

The subject came up after Martin collided with Mariners shortstop Carlos Guillen during the 2000 season. Describing the collision to a Seattle Times reporter, Martin likened it to a USC football game in 1986 when he tried to tackle Leroy Hoard of Michigan.

The Times did some checking and learned that USC didn’t play Michigan that year. In fact, Martin never played a down at USC and there was no record of him being on the team.

Confronted with that, Martin told the Times he would supply proof that he played for USC. He never did.