CHAPTER SIXTEEN

The Record 2001 Season

AFTER THEIR PLAYOFF RUN IN 2000, the Mariners established themselves as the team to beat for the division championship in 2001. They returned a nice mixture of speed, defense, starting pitching, veteran leadership, a solid bench, and that outstanding bullpen.

The Mariners believed they were a good team. How good? Nobody quite knew.

For the second straight season, the Mariners had to replace the anchor to their offense.

In 2000, they overcame the loss of Ken Griffey Jr. This time it was shortstop Alex Rodriguez, who became a free agent and signed a 10-year, $252 million contract with the Texas Rangers. He had led the Mariners with 41 home runs and a .606 slugging percentage in 2000, plus 132 RBIs and a .420 on-base percentage that were second on the team to DH Edgar Martinez.

The greater concern in Seattle was how the M’s would make up for his lost offense.

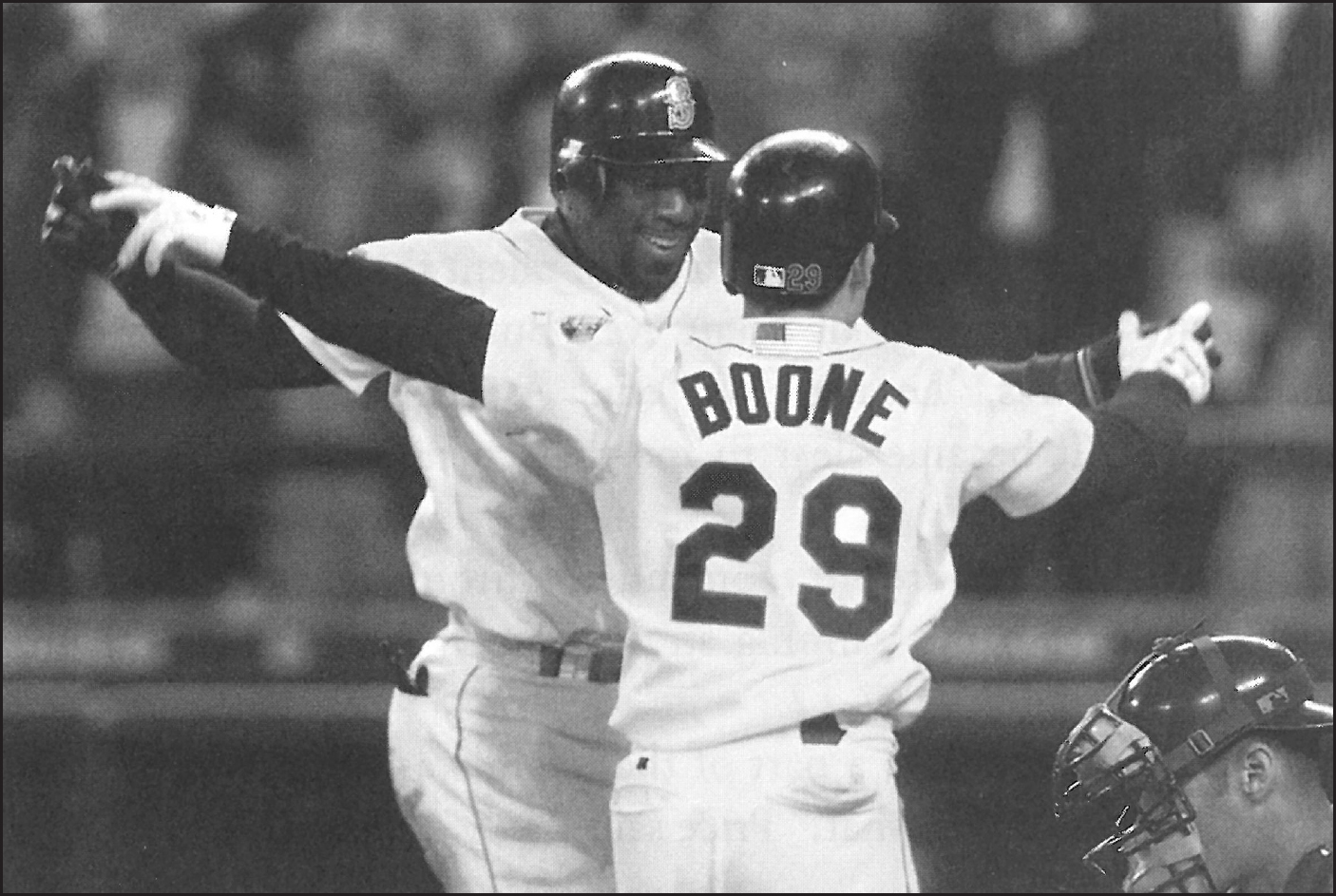

Part of the solution was Bret Boone, a free-agent second baseman whose knee problems in 2000 thwarted what had begun as a nice season offensively. Boone gave the Mariners much more than anyone expected. He hit 37 home runs, drove in 141, and narrowly missed winning the American League MVP award. He lost that honor to another newcomer who became an instant hit, not only in Seattle but around the major leagues.

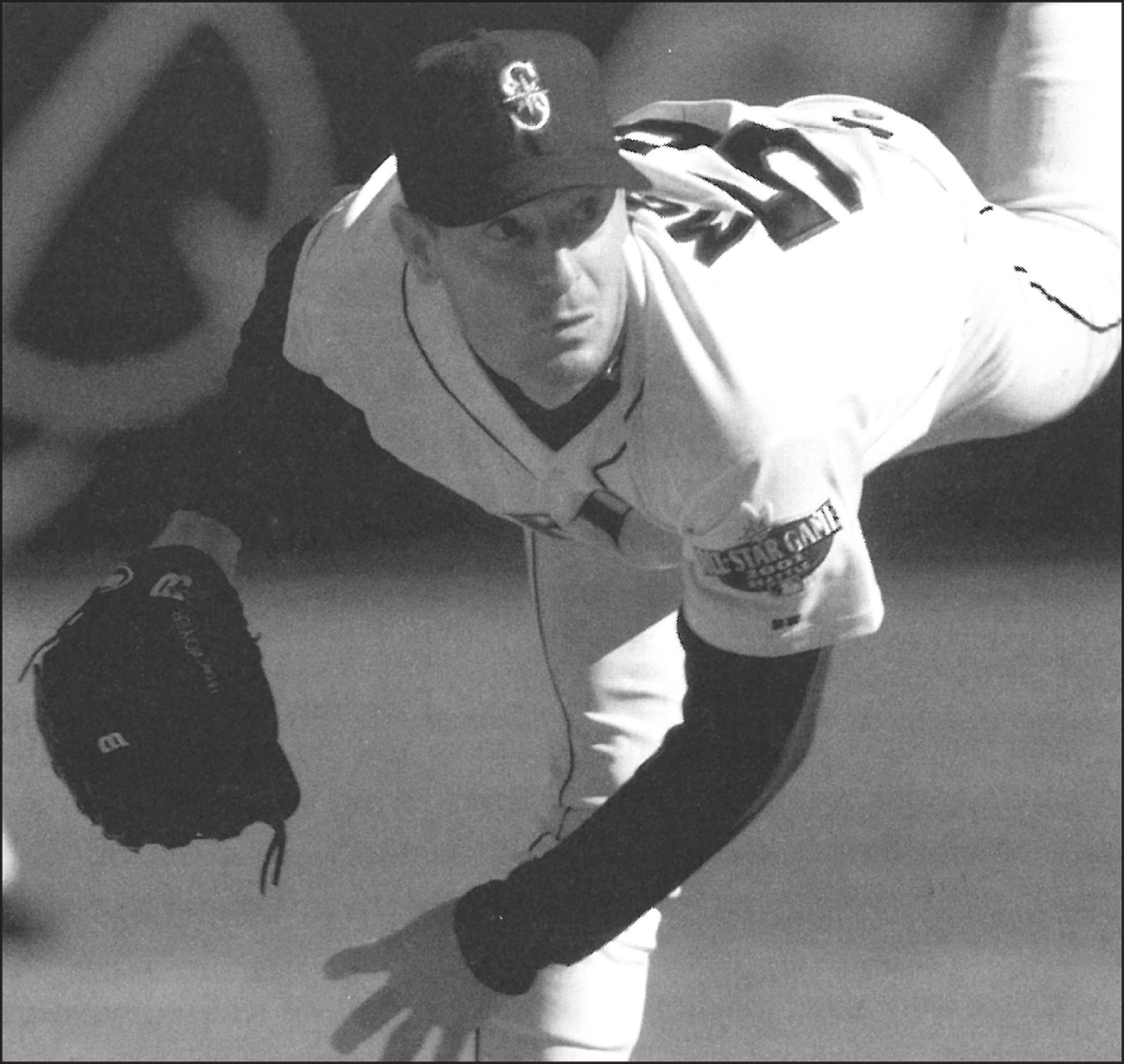

Jamie Moyer pitches against the Cleveland Indians in Game 2 of the 2001 ALDS. Photo by Michael Oleary/The Herald of Everett, Washington

Ichiro Suzuki, the first position player to come to the majors from Japan, became the leadoff hitter that the organization had sought from the beginning in 1977.

Suzuki used his slap-hitting approach and blazing speed to lead the league with 242 hits—most ever by a rookie—a .350 average and 56 steals. He irritated pitchers with his ability to make contact with anything in or out of the strike zone, and his speed forced opposing infielders to play him shallow, opening lanes for base hits. Once on base, he forced opponents into mistakes.

Suzuki won both the American League Rookie of the Year and MVP awards.

Boone and Suzuki became the perfect additions to a lineup that already featured the potent bats of Edgar Martinez, Mike Cameron, and John Olerud.

On the mound, the Mariners didn’t have a true ace in the starting rotation, but they rolled out five starters who gave them a chance to win every day. Backed by the improved offense and the best defensive team in the league, the starters flourished. Veteran Jamie Moyer won 20 games for the first time in his career, going 20–6. Freddy Garcia went 18–6, Paul Abbott 17–4, Aaron Sele 15–5, and John Halama 10–7.

The bullpen became the strongest in team history, with Norm Charlton, Jeff Nelson, and Arthur Rhodes forming a perfect left-right-left setup for Japanese closer Kazuhiro Sasaki, who set a single-season franchise record with 45 saves the previous year.

The combination of offense, defense, and pitching carried the Mariners to an incredible 116 victories, tying the 1906 Chicago Cubs’ major-league record for most victories in a season and breaking the 1998 New York Yankees’ American League record of 114.

“Once we started playing in spring training, we realized we were pretty good,” Cameron said. “But we didn’t know we were going to be that good.”

Playing a second straight year without a departed superstar, the Mariners succeeded because of their strength throughout the roster and manager Lou Piniella’s practice of playing versatile Mark McLemore regularly while giving the starters frequent days off. Every player on that team performed a key role in the successful season, and they maintained a killer instinct that didn’t wane as they built a big lead in the standings.

“We would win eight games in a row and then lose the ninth one 3–2, and guys were flat-out pissed off because they’d lost a winnable game,” pitching coach Bryan Price said. “We had that rare sense over the entire season that we were going to win 100 percent of the games. At no time did we ever feel we were out of a game.”

Bret Boone and Mark McLemore celebrate at home plate during the Mariners’ record 116-win season in 2001. Photo by Stephanie S. Cordle/The Herald of Everett, Washington

The Mariners beat Oakland 5–4 in the season opener at Safeco Field and never cooled off. They won 20 of their first 24 games in April.

“There were so many things we did well,” Cameron said. “We hit and pitched well, we hit with people on base and our situational play was unreal.”

When the Mariners needed a ground ball to push a runner from second to third with nobody out, they did it without worrying about the dip in batting average. They used the big gaps at Safeco Field to drive extra-base hits and cut down on rally-killing strikeouts. Most of all, they pitched well, played great defense and, with that strong bullpen, needed only to have a lead after six innings to virtually ensure victory.

“We could feel that other teams were weary, or maybe leery, of playing us,” Boone said. “They knew if they made a mistake, we were going to beat them. What’s incredible is that the group we had was the farthest from being an arrogant group of guys. It was the most humble team I’d ever played on, but it was a confident team.”

Edgar Martinez, John Olerud, Dan Wilson, and Stan Javier were the quiet backbone of the 2001 Mariners. Boone walked with a swagger but absorbed as much needling from his teammates as he dished out. Cameron lifted the clubhouse with his smile. And Piniella, of course, pulled it all together with his intensity.

“For years and years in my career, I never thought much of the cliché that teams click because of chemistry,” Boone said. “You have good players, you win. We had a lot of talent that year, but it wasn’t the greatest assemblage of talent ever. But when game time came, the attitude was, ‘Let’s go get ’em.’ As the season wore on, it snowballed. It became clear to me that chemistry is important in this game.”

The Mariners’ romp continued through May and June, including a 15-game winning streak from May 23 to June 8 that raised their record to 47–12.

“Anybody who was a part of that team was blessed to be going through a season like that,” Price said.

September 11: Tragedy Amid Their Greatest Triumph

The Mariners were in cruise control at the All-Star break, with a 63–24 record and a 19-game lead over second-place Oakland in the AL West. Eight Mariners made the American League All-Star team—Bret Boone, Mike Cameron, John Olerud, Edgar Martinez, Ichiro Suzuki, Freddy Garcia, Jeff Nelson, and Kazuhiro Sasaki—in a game that became a Seattle showcase. Played at Safeco Field, the AL won 4–1, and Sasaki recorded the save.

The All-Star break hardly cooled off the Mariners. They went 53–22 the rest of the season and won the division by 14 games over Oakland. The Mariners didn’t lose more than two games in a row until the final month, a testament to the focus of a veteran team.

As August turned into September, only two questions remained: Would the Mariners stay hot and beat the 1906 Cubs’ major-league record of 116 victories in a season? And when does the World Series start?

The Mariners could almost taste the champagne after they beat the Angels 5–1 on September 10 to begin a three-game series at Anaheim. It gave the Mariners a 17-game lead over Oakland with 18 to play, leaving them on the verge of the organization’s third American League West Division championship. Better yet, the Mariners won for the 104th time, pushing them closer to the 116-victory mark.

They went to bed that night at the Doubletree Hotel in Anaheim enjoying one of the most successful seasons a team has ever accomplished. The next morning, they woke up to horror.

Ron Spellecy, the Mariners’ traveling secretary, was rattled awake by the ring of his cell phone. His girlfriend was calling from Seattle.

“Are you watching the news?” she asked.

“Hello? Its 6:30 in the morning,” Spellecy said.

“Just turn on the news,” she said, without telling him why.

Spellecy grabbed the clicker and turned on the TV, but he couldn’t comprehend what was happening. Commentators were talking about an emergency at the World Trade Center in New York, and cameras were focused on smoke billowing from one of the twin towers.

“Just then, I saw a plane go into the second tower,” Spellecy said. “I sat there thinking, ‘This can’t be true. Who’s playing this game? It can’t be happening.’”

It was, and soon Spellecy and the Mariners learned how little baseball mattered. The world changed on September 11, 2001.

Nineteen men affiliated with al Qaeda had hijacked four planes on the East Coast, crashing two of them into each of the World Trade Center’s twin towers and another into the Pentagon. A fourth went down in a field in Pennsylvania, apparently headed toward the US Capitol building before passengers wrestled control away from the hijackers.

Stunned by the daylong reports from the East Coast, playing a baseball game didn’t seem important to the Mariners. That night’s game against the Angels was called off.

“There were so many real-life things going on that were important besides baseball,” Cameron said. “What happened put things in perspective to the point that the game itself wasn’t important. It put a halt on all that we had accomplished to that point in the season, but what could we do? It’s life we were dealing with.”

The Mariners spent the day glued to the TV and wondering when they would play again. What about the final game of the Anaheim series the next day? And the four games that were scheduled Thursday through Sunday in Seattle against the Texas Rangers? With air space closed because the threat to U.S. security remained uncertain, how would the Mariners get home for those games?

Spellecy booked a banquet room and called an afternoon meeting of players, coaches, team executives, families, and media to try to answer those questions. General manager Pat Gillick and Spellecy addressed the group, neither able to deliver a firm plan of what would happen the next few days.

“We’re going to sit here in Anaheim until we know what we’re going to be doing,” Spellecy told everyone. “Right now, this game has been cancelled. We don’t know about the next day.”

On Thursday, September 13, commissioner Bud Selig announced that baseball wouldn’t resume until the following Tuesday, September 18.

“When they finally made the call to postpone, that’s when we said, ‘Oh crap! How do we get all these people home?’” Spellecy said.

The Mariners’ traveling party in Anaheim was larger than usual, with several families along to visit Disneyland.

“We lined up four buses and told everyone that we were going to leave at 11 o’clock on Friday morning and ride back to Seattle,” Spellecy said. “It was going to be a 20-some-hour trip.”

The Mariners didn’t abandon hope of arranging a flight back to Seattle, but that seemed futile because airspace remained closed.

“I was calling all my contacts within the airline industry, but everything was cancelled, and nobody knew when they would be flying again,” Spellecy said. “Then, Pat Gillick said, ‘Why don’t you call Alaska back?’”

Spellecy did, hoping for the off chance that Alaska Airlines would have a plane in Los Angeles that could transport the Mariners to Seattle if flights resumed. The airline’s response was as uncertain that day as it had been since the 9/11 attacks. Nobody knew when airspace would reopen, and when it did, nobody knew what regulations or limitations there would be.

“That’s fine,” Spellecy said. “Just keep us in mind.”

On Friday morning, the Mariners’ equipment was loaded onto a truck and it left about 9 a.m. to begin a drive of nearly 1,200 miles to Seattle. The four buses were scheduled to arrive at the hotel about an hour later, and Spellecy held another briefing with the team to discuss the trip back to Seattle.

About 30 minutes later, his cell phone rang. It was an official from Alaska Airlines.

“We have a plane. It’s at LAX and it’s yours if you want it,” Spellecy was told. His response was brief but emphatic.

“Yes! We want that flight!”

Just then, four buses rounded the corner and pulled onto the hotel grounds, ready for the long journey to Seattle. The Mariners used those buses, but only for the drive from Anaheim to Los Angeles International Airport.

Gillick held one last meeting to tell everyone of the change in plan—that the team would fly back to Seattle, not bus—and he emphasized that the threat to US security remained uncertain and that the situation was still serious.

“If there’s one practical joke or if anybody doesn’t go through security, if you’re carrying anything you shouldn’t or if you make bad jokes, you’re going to be in deep, deep trouble,” Gillick said. “This is not fun and games. Have your IDs ready. Have your passports ready. Don’t mess this up.”

“We had to make it very, very clear to everybody flying with us how serious this was,” Spellecy said.

That became apparent during the drive to the airport. Four cars from the Orange County Sheriff’s Department escorted the Mariners’ buses, and the freeways around Los Angeles were nearly deserted. So was LAX when the team arrived.

“It was such an eerie feeling,” Spellecy said. “It was desolate going up there. Nobody was driving. We were going 70 miles an hour on the freeway, and the traffic was maybe the quietest it’s ever been in LA. I think people were staying home wondering, ‘What’s going to happen next?’”

The buses arrived at the airport and the Mariners entered a terminal deserted of anyone but a few airline workers and numerous law enforcement officers.

“There were police standing all over the place when we got to the airport, but even they didn’t really know what was going on,” Spellecy said. “We had to take our luggage and check it, but the people with the airline had no idea what was going on, either. They hadn’t been working for three or four days, and then all of a sudden it’s open. There was a lot of confusion, and it took us a while to get on the plane.”

When the Mariners finally boarded the plane and settled in their seats, the pilot made a brief announcement before takeoff.

“We’re the only plane leaving right now,” he said. “Welcome aboard and let’s get out of here.”

The Mariners were never so glad to hear those words.

Life After 9/11

The Mariners had to get their minds back on baseball when games resumed on Tuesday, September 18. It wasn’t easy.

The terrorist attacks still weighed on everyone’s mind, and every jet that flew over Safeco Field on its approach to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport became a nervous reminder of what happened a week earlier.

Everyone who attended the first game back against the Angels received a small American flag, and pregame ceremonies brought tears to a lot of eyes. Between “God Bless America” and the “Star Spangled Banner,” the sellout crowd broke into a loud chant of “U-S-A! U-S-A!”

Manager Lou Piniella called it a beautiful moment, and third baseman Mark McLemore was like many of the players, having to dig deep for the focus needed to play the game.

“I was pretty much a wreck until the first inning,” McLemore said.

They all felt a responsibility to get back on the field and give America a diversion from what had occurred on the East Coast a week earlier.

“We were going through one of the roughest times in this country’s history, and the people needed baseball as something to get their minds off everything on TV that was so negative,” second baseman Bret Boone said. “I felt a responsibility as an athlete, as an entertainer, to go back to work and for three hours a night allow people to watch a ballgame and get their minds off it. That was our obligation to the country.”

Pitcher Freddy Garcia did his part in the first game back, pitching a three-hit complete game in the Mariners’ 4–0 victory over the Angels. That cut the magic number for clinching the division title to one—an Oakland loss or a Mariners victory would give the M’s their third division championship.

That could happen the next night, and the Mariners knew that their victory celebration would be seen, and probably critiqued, nationwide. They knew it needed to be tasteful and not the raucous, champagne-spraying delirium that is common when baseball teams win championships.

“We talked for a week about how we should do it,” Cameron said. “We knew we had to do it in a respectful way.”

Oakland lost to the Texas Rangers, and the Mariners beat the Angels, clinching the third division championship in franchise history. When closer Kazuhiro Sasaki got Jose Nieves on a popup to Boone for the final out of a 5–0 victory, there was no massive pileup of players on the field.

Instead, the Mariners hugged each other and waved to the crowd. McLemore took an American flag and walked to the top of the pitcher’s mound, waving it as his Mariners teammates gathered nearby.

“McLemore had talked a little about doing that,” bench coach John McLaren said. “But the way it unfolded, it was spontaneous.”

The players, coaches, and Piniella all dropped to a knee on the mound and bowed their heads for a moment of silence. The stadium fell silent, except for some who sobbed at the scene. The emotion overwhelmed Mariners utility player Stan Javier, who broke down and cried.

Then the players rose to their feet and made a slow walk around the diamond, led by McLemore with the American flag. The crowd cheered loudly, but with respect.

Relief pitcher Arthur Rhodes broke from the pack of players and ran down the left-field line, where he stopped and embraced a police officer.

Edgar Martinez holds an American flag during pregame ceremonies at Safeco Field in 2001 when baseball resumed after the 9/11 attacks. Photo by Dan Bates/The Herald of Everett, Washington

Players took turns carrying the flag around the diamond, and when they reached home plate, Cameron and Piniella held it aloft. The players smiled, waved and then retreated to the clubhouse for their own private, but still respectfully quiet, celebration of the division title.

“We had a little champagne because we’ve worked hard,” Piniella said. “It was subdued and it was in very good taste.”

With the division championship secure and still 16 games remaining in the season, there were more important matters than an all-out effort to beat the single-season record of 116 victories. The Mariners needed to go 11–5 the rest of the way to do that, and it was entirely possible on this team, but Piniella knew it was more important to get them ready for the playoffs. The first step was to give the regulars plenty of rest in the final two weeks of the regular season.

Piniella did that, and the Mariners lost four straight, leaving them stuck on 106 victories with a dozen games remaining.

“We had to win 10 of the last 12 to tie the record,” Cameron said. “I’m not sure how many in a row we won, but we were playing very, very well by the end of the season.”

The Mariners won nine of the next 10, leaving them one victory from tying the record with two games remaining in the regular season. They got it in the next-to-last game, beating the Rangers 1–0 on October 6 when minor-league call-up Denny Stark led a parade of five Mariners pitchers to the mound as Piniella tuned up his staff for the playoffs.

The Rangers won the final game 4–3, scoring a run in the top of the ninth, to leave the Mariners with 116 victories.

Illness Strikes a Star

Along with their great baseball, the Mariners were blessed with good health most of the 2001 season. Injuries to front-line players were minimal.

Outfielder Jay Buhner missed all but the final month because of an injury to his left foot. Norm Charlton, Edgar Martinez, and Stan Javier all spent time on the 15-day disabled list with leg issues, but they returned to play key roles in the Mariners’ drive to the division championship.

Manager Lou Piniella rotated his lineup, giving starters frequent time off in order to keep everyone fresh through the heat of the summer.

It was all working well until shortstop Carlos Guillen got sick in September.

“He’d had problems off and on the whole year,” head athletic trainer Rick Griffin said.

Guillen said nothing about feeling sick, but he’d experienced nosebleeds during the season and missed several games.

“The 10 days when he was really suffering, he hit over .400,” Griffin said. “He could get himself through the games, but then he’d go home feeling bad, and he was coughing up blood.”

Guillen underwent tests, and on September 28 his problem was diagnosed as pulmonary tuberculosis. He was hospitalized immediately and placed under quarantine because of the highly contagious disease.

“Carlos probably contracted it from someone when he was home in Venezuela,” Griffin said. “He was toughing it out. But if it had gone on much longer without treatment, it could have become extremely serious.”

Guillen’s teammates became very worried because the disease can be spread via airborne particles, and they had spent considerable time in close quarters on flights, buses, and in clubhouses.

Every Mariner was tested for TB, and nine players tested positive, meaning they had contracted the disease although they hadn’t shown symptoms of illness. Those nine, whose names were never revealed, took medication for the next nine months.

Guillen missed the rest of the regular season, plus the first-round playoff series against the Indians. He started the first game of the American League Championship Series against the Yankees but physically wasn’t able to play every game of the series. He pinch hit in Game 3 and started Game 5, getting two hits in his eight at-bats in the series.

Postseason Disappointment

History said the Mariners should have reached the World Series in 2001.

Of the 23 other teams in baseball history that had won 105 or more regular-season games, only the 1998 Atlanta Braves failed to reach the World Series.

This, however, is the era of divisional play and two rounds of playoffs just to reach the World Series. No matter how successful the regular season was, it took a hot team to advance through the division series and league championship series.

The Mariners never found their regular-season rhythm in mid-October.

Perhaps it was the letdown after the push to win 116 games. Perhaps it was the illness to Carlos Guillen. Perhaps it was the strained oblique suffered by unsung infielder David Bell during a workout after the 9/11 attacks. Bell, who batted .260 with 15 home runs in the regular season, hit .188 in the postseason.

Indians ace Bartolo Colon shut out the Mariners on six hits in a 5–0 victory in Game 1 of the AL Division Series at Safeco Field, but the Mariners came back the next day behind left-hander Jamie Moyer, who held the Tribe to one run. The M’s scored four times in the first inning off Indians lefty Chuck Finley and held on for a crucial 5–1 victory.

Having gained a split of the two games at Safeco Field, the Indians believed they had the momentum with the best-of-five series shifting to Cleveland for Games 3 and 4.

The third game was a nightmare for the Mariners. The Indians pummeled Seattle starter Aaron Sele, who had never won a postseason game, with four runs in the first two innings and didn’t let up against three Mariners relievers. The Indians won 17–2 and celebrated afterward as though they had the series in their pockets. All they needed was one more victory to celebrate in earnest.

The next day, before Game 4, Mariners CEO Howard Lincoln sat in the dugout at Jacobs Field, on the brink of seeing his magnificent team eliminated in the first round of the playoffs. What irritated him most was how the Indians reacted to their Game 3 victory.

“Those guys were jumping around yesterday like they’d already won the series,” Lincoln said. “There’s nothing more I would like than to beat those guys.”

With their marvelous season one loss from crumbling, the Mariners rallied. They came from behind and beat the Indians 6–2 in Game 4, then clinched the series when Jamie Moyer outpitched Chuck Finley in a 3–1 victory at Safeco Field.

The Mariners, who observed their division championship with a subdued celebration three and a half weeks earlier, sprayed champagne this time. It was their last joy.

Andy Pettitte held the Mariners to three hits in eight innings, leading the Yankees to a 4–2 victory in Game 1 of the ALCS at Safeco Field. The next night Mike Mussina beat them 3–2, leaving the Mariners in a dire hole as they prepared for the next three games at Yankee Stadium.

Reporters, waiting outside the Mariners’ clubhouse before being allowed access to the players, were surprised to see Lou Piniella when the doors burst open. On his way to the required postgame press conference, he stopped and delivered a bold statement.

“Let me interject one thing,” Piniella said with fire in his eyes. “We’ll be back here to play Game 6! I’ve got confidence in my baseball club. We’ve gone to New York and beaten them five of six times. We’ll do it again! We’ve got another five games to play!”

To do that, the Mariners had to win at least two of the next three games at Yankee Stadium, where they had indeed dominated the Yankees in the six regular-season games in New York.

Returning there in October, however, was different.

The Mariners were playing a Yankees team that suddenly had gained the empathy of the nation, because they represented a city that continued to suffer from the September 11 terrorist attacks.

The Mariners had the right man pitching in Game 3, Jamie Moyer, and they played their best game of the postseason. Moyer held the Yankees to two runs in seven innings, and the Mariners broke out with seven runs in the sixth inning, rolling to a 14–3 victory.

It not only pulled them back into the series, it gave the Mariners a sense of energy they hadn’t shown in the postseason. The killer instinct that had been such an important part of the regular season finally had returned.

One day later, before the biggest game of their season, all of that energy seemed lost.

Piniella, his coaches, front-office executives, and several players took a bus to the site of the World Trade Center. They met firefighters at Firehouse 24, Ladder Co. 1, the home station of several who lost their lives on September 11. They met families of lost firefighters and police officers. Then they toured the ruins of the World Trade Center, smoke still drifting from the pile of twisted steel and the smell of sulfur lingering in the air.

“After seeing that, how do you put baseball in the same context?” pitching coach Bryan Price wondered. “How do you make baseball the priority? It was a very, very difficult thing for us to do.”

Head athletic trainer Rick Griffin, who was on that bus, also sensed a change in the team.

“We saw first-hand the devastation,” he said. “We met relatives of people who were lost. We met people who survived. We met wives of the firefighters whose husbands had been buried alive. This was a close-knit team and they were very family-oriented, and they were really affected. It took the focus away from baseball.”

That night in Game 4, the Mariners and Yankees were scoreless through seven tense innings. Before the top of the eighth, second baseman Bret Boone did his best to instill a spark by giving his teammates a dugout lecture.

“If any of you want to make it to that postgame interview room, then you’d better do something this inning,” Boone yelled.

Boone, the third hitter up in that inning, knew the Mariners needed to score in the eighth because they’d face the Yankees’ dominating closer, Mariano Rivera, in the ninth. Ichiro Suzuki grounded out and Mark McLemore lined out, bringing Boone to the plate with two outs against right-hander Ramiro Mendoza.

Boone drove a pitch from Mendoza deep to left-center field, clearing the wall for a 1–0 Mariners lead.

With two of their best relievers ready to close out the Yankees—Arthur Rhodes in the eighth and Kazuhiro Sasaki in the ninth—the Mariners should have been in a perfect position to even the series at two victories apiece. The left-handed Rhodes would face two of the Yankees’ tough left-handed hitters, David Justice and Tino Martinez, but in between them was dangerous switch-hitting Bernie Williams.

“I thought we had it in the bag then,” Boone said. “But then, in that next inning when I went out to the field, it was like a weird thing was happening. The wind started swirling and I remember seeing hotdog wrappers flying around.”

Rhodes struck out Justice, but he fell behind in the count to Williams before working his way back to a full count. Then Rhodes went to his best pitch, a 95-mph fastball.

Williams made contact, but not good contact, lofting an innocent-looking high fly to right-center field. It looked certain to be the second out of the inning.

“That ball was a can of corn,” Boone said. “You can tell when a ball goes over your head if it’s hit well, and Bernie didn’t get all of it. I almost held up my hand and said, ‘Two down!’”

The wind grabbed that ball and carried it over the fence, tying the score 1–1.

“Here I am thinking that ball’s going to be caught close to the warning track, and it winds up five rows deep,” Boone said. “That’s when you start believing in the ghosts at Yankee Stadium.”

Rhodes got Martinez and Jorge Posada to end the inning, and Rivera rolled through the Mariners 1-2-3 in the top of the ninth.

Sasaki took the mound for the bottom of the ninth and promptly gave up an infield single to Scott Brosius, then faced young second baseman Alfonso Soriano, who had flashed some power with 18 home runs in his first full major-league season.

Like the pitch Williams hit off Rhodes in the eighth, Soriano drove this one off Sasaki high in the air and the wind helped do the rest, carrying it over the fence in right-center to win the game, 3–1.

“That was the turning point the series,” Boone said. “We win that game, we win the series. But now our backs are against the wall as much as they can be.”

They never had a chance.

The Yankees scored four runs in the fourth inning of Game 5 off Aaron Sele and didn’t let up. The Mariners trailed 12–3 when they batted in the top of the ninth, and the boisterous crowd at Yankee Stadium had worked itself into a frenzy.

The cheering and stomping became more intense with each out in the ninth, and the fans dished Piniella’s words back at him with the chant “No Game 6! No Game 6!” When Mike Cameron lined out to end the series and send the Yankees to the World Series, fans literally shook the stadium.

In the visiting dugout, Piniella, the man who detests losing any game, anywhere, any time, absorbed the defeat with compassion for a city that had waited six brutal weeks to have something to cheer.

“About the eighth inning, when the fans were really reveling in the stands, the one thought that came to my mind was that, boy, this city suffered a lot and tonight they let out a lot of emotions,” Piniella said in the postgame news conference. “I felt good for them in that way. That’s a strange thought to come from a manager who’s getting his ass kicked.”

For all that the Mariners accomplished in the 2001 regular season, the series loss to the Yankees was a bitter disappointment, especially after they had dominated the Yanks during the regular season.

Perhaps it shouldn’t have been a surprise.

The drive to 116 victories took a life of its own as the Mariners gained national exposure in trying to become one of the most successful teams of all time. By the end of the season, it wore on them.

“The media scrutiny became so heavy down the stretch that year,” Boone said. “I don’t want to make an excuse, but that might have been our downfall.”

When the Mariners won their record-tying 116th game by beating the Rangers on the next-to-last day of the regular season, a sense of relief swept the clubhouse.

“Everybody in that room looked at each other and sighed like finally we did it,” Boone said. “Then we realized, wait a minute, we’ve got to play the postseason now.”

The postseason was a struggle and, despite the opening-round victory over the Indians, the Mariners couldn’t regain the momentum that carried them through the previous six months.

“We didn’t play very well against Cleveland and beat a great team,” Boone said. “We didn’t play very well against the Yankees, nor did they, but they got a couple of timely hits and won the series. I look back on it now and see how we came up short.”