A Brief History

“History is a kind of introduction to more interesting people than we can possibly meet in our restricted lives; let us not neglect the opportunity.”

DEXTER PERKINS

The Early Years

Genius is fascinating. Not the mere possession of a high intelligence quotient, but the gift of an innate talent to create something entirely new, something that has not existed previously. This capacity is exhibited in vastly diverse ways. Consider: Mozart, Einstein, Michelangelo, Newton, Ramanujan. One common factor among most creative geniuses, whether in the arts or sciences, is that their primary contributions occur when they are young. Wisdom may come with age, but genius is innate and typically manifests itself early.

Charles Sumner Greene was a genius. He and his brother, Henry Mather Greene, didn’t set out to be among America’s most accomplished designers. They trained as architects and set about the practice of that profession. Henry, the more logical of the two, may have been well pleased with this career choice. However for Charles, an artist at heart, it was a concession to his father. Like many fathers before and since, Thomas Greene wanted proper professions for his sons. Bohemian artist didn’t fit that bill. For an artistically minded young man, however, architecture would at least provide an outlet for creative energies.

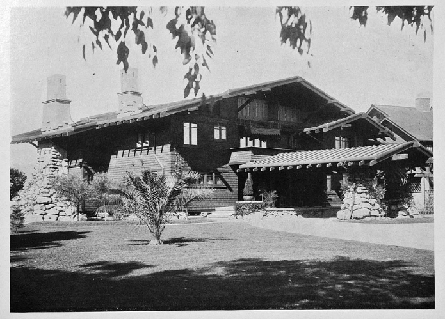

The house for James Culbertson signaled the arrival of Arts & Crafts in the Greene & Greene office including the first use of Stickley furniture by the firm. Southeast façade, James A. Culbertson house, Pasadena, 1902-14.

Thomas Greene, a Civil War veteran, married Lelia Mather of West Virginia in 1867. The young couple settled in a working-class section of Thomas’ native Cincinnati. They were joined, in short order, by Charles on October 12, 1868. Henry followed little over a year later on January 23, 1870. In 1874 the family moved to St. Louis where they remained, aside from a three-year return East while Thomas attended medical school, until Charles and Henry graduated college. The family enjoyed a comfortable lifestyle during the boys’ childhoods.1

By the last decade of the 19th century, the industrial revolution had been gaining momentum for roughly 100 years. The effects were far-reaching, influencing every aspect of human life. The move toward manufacturing resulted in a significant reduction in the traditional trades. For centuries, trades had been passed from master to apprentice or father to son. In the industrialized world, this was often no longer the case. Thus, many young men outside of agricultural areas might receive no training in the use of tools. Supporters of the manual training movement 2 sought to remedy this through a curriculum that included classical academic subjects, such as English and physics, along with drafting and shop training in both wood and metal.3

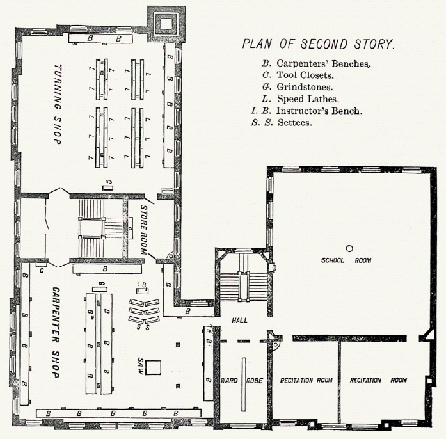

Calvin Woodward, first Dean of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis, was a proponent of technical education. In particular, he believed that it was important for boys to be skilled in the use of tools in preparation for a career in an industrial society. In 1879 he opened the Manual Training School of Washington University. The purpose of the three-year curriculum was, as Woodward put it, to train the head, heart, and hand — “The cunning mind, the skillful hand”4 in the words of the school’s motto. It was not the goal of the school to create craftsmen or tradesmen. Fitting with Woodward’s beliefs, the program strove to prepare boys for the varied activities of careers in a quickly evolving society, particularly careers in engineering and related fields. Charles entered the Manual Training School in 1884 and was followed a year later by Henry.5

The Manual Training School of Washington University provided sound fundamental training that would prove valuable to Charles and Henry during their careers.

Though the boys could not have known it, their education at the Manual Training School would figure quite prominently in their architectural careers. The first-year woodworking curriculum included courses in woodcarving, carpentry and joinery.6 Furniture designs by architects are often visually striking, but are not always well-designed with respect to function and construction requirements. Greene & Greene furniture is an exception. Their pieces are typically quite functional and well-engineered. Their knowledge of woodworking certainly plays a role in this regard.

The curriculum of the Manual Training School of Washington University required students to achieve proficiency in making a number of woodworking joints ranging from simple mortise and tenon to standard dovetails to complex mitered double mortise and tenon. Even a rafter joint is covered.7 Though Charles and Henry certainly would not have gained skills nearly as advanced as the craftsmen who would later implement their designs, their knowledge of joinery would allow effective communication with the craftsmen. More importantly, effective joinery is the key to well-constructed furniture. Thus, Greene & Greene proved to be case studies for the intended purpose of manual training.

Charles Greene’s calling card.

From St. Louis, the brothers moved to Boston to pursue the study of architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. MIT offered two- and four-year programs — Charles and Henry enrolled in the more typical, for that time, two-year course of study which they completed in 1891, a year later than planned. During and after their time at MIT, each engaged in internships and apprenticeships with prominent local firms.8

In 1892 Thomas and Lelia Greene moved to California with the hope that the climate would improve Mrs. Greene’s asthmatic condition. That the area was a healthful oasis is part of the Southern California mythology. Begun in 1857 with the publication of Climatology of the United States, by Lorin Blodget, the legend could do little more than taunt the Eastern populace as California must have seemed impossibly remote. In the 1880s however, the advent of relatively inexpensive rail travel made it possible for many infirm to make the pilgrimage. While some did recover their health, many others were less fortunate.9 Who can say how many of the success stories accrue to beneficial effects of climate?

The Greenes settled in Pasadena, drawn by the warm, dry climate that also attracted many wealthy families from the East and Midwest. The climate was not the only draw. Located at the foot of the San Gabriel mountains, Pasadena was, and is, a place of surpassing beauty. An arroyo seco — Spanish for dry river bed — nestled between the mountains and the town provided recreation for inhabitants as well as ample land for livestock and citrus groves. Very much a part of the frontier, Pasadena provided an appealing, even tempting, mix of climate, topography, nature and seemingly boundless possibilities. In short, the California dream.

Charles and Henry arranged in 1893 to follow their parents to Pasadena, arriving late that year. Pasadena at that time was a very small city quite distinct from Los Angeles and already home to several architects. It was not obvious that there was need of another architectural office to serve the limited population that existed there at that time. It is even less obvious that two young men with very little experience would be able to compete. Despite these apparent obstacles, in January 1894, Charles, 24 years of age, and Henry, 23, established their practice, Greene & Greene Architects.10 In September of that year they secured their first commission.

Houses for the firm’s earliest clients were modest though size and expense increased over the course of their first decade in practice. Designed in a variety of styles, these jobs constitute an eclectic set. Some designs had an English flavor with timbering and leaded windows. Others bore elements of the California Mission style. Many are easily identifiable as Victorian, though somewhat subdued for that form. Their first house, for Martha Flynn, is not unlike the chalet style to which they would return in the next decade.11

There is, of course, no vice in the use of various styles. Nor is there virtue in uniformity merely for uniformity’s sake. In the Greenes’ case, the diversity they displayed early on is indicative that they had not yet discovered a philosophy with which they were at ease. At this stage of their nascent careers, the young architects were exploring, searching, learning about themselves and the strange surroundings that would play a significant role in shaping them and their aesthetic. It may also be that, due to their tender years, they were not yet comfortable suggesting the unanticipated to their clients. Perhaps they were simply designing what they thought, or were told, was expected of them.12 At the dawn of the 20th century, however, the Greenes found their own voice, a voice in harmony with their environment and an emerging philosophy, a voice that would define them for posterity.

The Glory of… Panels carved with natural scenes and quaint sayings were an important aspect of the Culbertson house. Carved panel, c. 1907, James A. Culbertson house.

James Culbertson continued to engage the Greenes for years. This wall lantern demonstrates the evolution that occurred between 1902 and 1907. Lantern, c. 1907, James A. Culbertson house.

A New Direction

By 1902, when Charles undertook the design and construction of his own home on a desirable site overlooking the arroyo, the Greenes’ aesthetic had become distinctly simpler than during the eclectic period comprised of the eight years since opening their practice. Oakholm, as the house was known, was in constant flux during the 13 years that Charles shared it with his wife, Alice, and their ever-growing family. It expanded with the family and evolved with Charles’ style, serving as a canvas on which Charles would test his evolving ideas. From the outset though, it was a departure from their earlier work.

In another project dating to 1902, the Greenes demonstrated their versatility in a house design for James Culbertson. Sited on a corner lot very near Charles’ own home and even nearer the arroyo seco, the English-style house was quite lovely.13 Beauty, however, is not the reason for the significant position of the Cul-bertson house in the firm’s progression. In James Culbertson, Charles found an enlightened client, one willing to indulge artistic excursions into new territory. In this case, the territory was that of the “Morris movement” including the first use of Stickley furniture in a Greene & Greene commission.14 Culbertson remained committed to artistry and growth, returning to the Greenes often for additions and modifications. In this way, by the close of the decade, the house would contain many elements of the Greenes’ mature style — a style that found the genesis of expression in this house.

The house designed for Mary Darling in 1903 continued Greene & Greene’s movement to an Arts & Crafts aethetic. Though not one of their grand commissions, it is clear in the Darling house that the trademark Greene & Greene style was beginning to emerge. Certainly many of the elements we associate with their work are absent, but enough others are present to make the structure recognizable as theirs: stained wood shingles, deeply overhanging eaves, a broad front door and numerous windows. Two large bays on the front of the house are supported by large rocks15 presaging use of the Japanese technique of anchoring posts on stones more directly adopted for the Arturo Bandini house later in the same year.

Though less polished than later pieces, this double sconce from the Jennie Reeve house is a wonderful example of decorative arts in early Greene & Greene houses. Sconce, 1903-04, Jennie A. Reeve house, Long Beach, 1903-04.

In the interior, an oversize brick fireplace, built-in cases and wooden sconce lighting mark the arrival in earnest of the Arts & Crafts sensibility begun during work for James Culbertson. Perhaps most significantly, for the Darling house Charles sketched complete roomscapes, incorporating Stickley furniture and standard Arts & Crafts decorative elements.16 This event is significant in that it signals Charles’ move into the realm of the gestalt. Henceforth, Greene & Greene would be increasingly involved in providing fixtures, decorative elements and furniture, rather than simply the structure.

If one were to create a genealogy of Greene & Greene clients, complete with all relationships, it might be natural to conclude that, were it not for referrals from earlier clients, the architects would have had a meager existence. Mary Pratt was a Vassar classmate of Caroline Thorsen. Caroline Thorsen’s sister was Nellie Blacker. Freeman Ford was a friend of Henry Robinson. Adelaide Tichenor was a close friend of Jennie Reeve. Jennie Reeve was Mary Darling’s mother. If this were truly a family tree, there would be a number of marriages between cousins. While the names Blacker, Thorsen and Pratt are associated with some of the Greenes’ greatest achievements, the last two relationships on the list are among the most significant.

Jennie Reeve was a pivotal client for Greene & Greene. She commissioned three houses in a span of four years, but volume was not the primary reason for her importance to the Greenes. She came to the firm at the dawn of their move toward designing complete environments and provided them the resources and freedom to move further along that path. For the Reeve house the Greenes designed 139 decorative objects including furniture, numerous lighting fixtures and built-in cabinets in addition to a well-documented living room inglenook.17 The Reeve furniture is quite simple compared to later pieces, even so it is indicative of developing trends. Architect Ted Wells has characterized the Reeve furniture as looking at the work of Gustav Stickley through a Japanese prism, a very apt description.18 Unusual for that time, the inglenook and stairs form a central island that can be circumnavigated via the living room, dining room and entry hall. The overall result was a wonderful success. One of the most significant aspects of the Greenes’ relationship with Jennie Reeve, however, was that she introduced the architects to Adelaide Tichenor

Hanging dining room cabinets appear in a number of Greene & Greene houses. Dining-room cabinet, 1903-04, Jennie A. Reeve house.

Adelaide Tichenor provided Charles Greene with the opportunity to design furniture for much of the house. The results provide a glimpse of what was to come. Bench, 1904-05, Adelaide M. Tichenor house, Long Beach, 1904-05.

In the pantheon of Greene & Greene clients, Adelaide Tichenor occupies a distinguished position. Mrs. Tichenor was a strong-willed, wealthy widow when she contracted Greene & Greene to design a large oceanfront house in Long Beach. The combination of her desire for a complete environment — even more so than Jennie Reeve she wanted an all-encompassing design including house, landscape, furniture, lighting and decorative arts — and her insistence on exploring a new aesthetic played a significant role in Charles’ artistic development. The relationship was not entirely pleasant for Charles, as Mrs. Tichenor did not allow him absolute freedom to implement the design according to his vision.19

In 1905, Greene & Greene Architects were presented with an opportunity to advance their practice by taking on a project of greater scope than any they had undertaken thus far. The previous several years had prepared Charles and Henry for the challenges of a project of a greater magnitude, for the design of a substantial landscape rather than smaller gardens, for the application on a grand scale of their new skills in the design of furniture and decorative arts. This opportunity came to them in the person of Laurabelle A. Robinson.

For the Robinson project, the Greenes were provided a beautiful parcel of land, a large budget and the charge to create completed interiors.20 In the hands of an artist, such as Charles, this happy set of conditions was sure to yield a very special result. And indeed it did. Given the distinct style of recent commissions, the Robinson house is something of an anomaly with its Gunite exterior bearing no resemblance to wood shingles. Though the exterior materials are distinct, many elements of their new and still emerging style remain: deep eaves with exposed rafter tails, integration of exterior spaces with the interior, a broad main entry door with decorative art glass, numerous windows, particularly on the West elevation to provide views of the arroyo below. Stylistically, the Robinson house defies easy categorization. The cementitious exterior evokes the California missions, but the house is clearly not mission; half-timbering recalls English forms, but the house is clearly not English; Asian elements abound but the overall effect is clearly not Asian. Despite this lack of identity, the whole is undoubtedly greater than the sum of its parts; the result is stunning.

For the interior, Charles designed a number of remarkable pieces of furniture. Best known are the dining room table and chairs and the spectacular, height-adjustable chandelier. The table introduces a form to which they would return for the Gamble house. The Robinson dining chairs evoke a Chinese design. The low-armed host and hostess chairs are particularly dramatic, a study in sublime, simple elegance. (This is a perfect example of the Japanese concept of shibusa. See Chapter 3 for more discussion of this topic.)

Set at the edge of the arroyo seco, the Robinson house makes a strong argument for the genius of Greene & Greene. At night, the Gunite exterior exudes a warmth and almost seems to glow. View of east façade, Laurabelle A. Robinson house, Pasadena, 1905-06.

The importance of the Robinson house derives not solely from the scale, which is imposing, but from what it demonstrates about the abilities and direction of Greene & Greene. In this house we see a new philosophy as, for the first time, rooms are distinguished by different themes. Uncharacteristic curves and low, broad forms in the living room. Asian-inspired themes in the dining room. A rather traditional Arts & Crafts influence in the den. A lighter, more characteristic Arts & Crafts feel in the entry hall. Yet the whole is cohesive and harmonious. While the Greenes were already known for attention to detail, the Robinson house presages the arrival of their near obsession in this regard and serves as an introduction to the firm’s most productive period, soon to come.

It is generally agreed that the increasingly rapid development of the Greenes’ trademark style from 1905 onward was enabled, in part, by a shop of talented craftsmen able to implement their designs. Not coincidentally, during 1904 their firm began working with contractor Peter Hall and, soon thereafter, his brother John Hall.21 The Halls, Scandinavian-born woodworkers, came to Pasadena in the late 19th century. By the time they began collaborating with the Greenes, they had significant experience in construction and cabinetmaking. This provided the Greene firm with consistent, high-quality, one-stop shopping — the Halls and their craftsmen could implement almost every aspect of the ever more complex commissions. This included general construction, intricate finish carpentry and exquisite furniture.

The relationship between the Greenes and Halls was highly interactive. Examining original drawings, one can see evidence of this. One drawing, for a Pratt house desk, bears the notation, “Layout shelves and submit to architects.”22 Trust and mutual respect had fostered a synergy that benefited both the Greenes and the Halls but more significantly, the clients as well. By the time construction began on the Pratt house in 1909, Charles Greene and John Hall could likely read each other’s minds. Charles was known to visit the Halls’ shop almost daily to inspect, change and even help construct his works in progress. This collegial rapport continued through, and beyond, the timeframe of the Greenes’ most industrious phase.

In the Robinson interior, we see details that are unusual for Greene & Greene, as in the curves on the front of this cabinet and the mantle across the room. Living-room cabinet, 1905-06, Laurabelle A. Robinson house.

That the Halls were significant in the success of the Greenes is neither hyperbole nor revisionist. To understand why, one need only look at Greene & Greene furniture constructed prior to the Greene-Hall collaboration. Pieces designed for the Tichenor house serve as examples. Tichenor pieces are interesting — they lack the grace and refinement of later work, but the designs are successful, their heritage identifiable. In particular, lifts and pegs are conspicuous if not yet fully developed. In execution, however, these pieces are clearly inferior to the Halls’ work. Stock selection is particularly suspect with wild, unattractive grain dominating and detracting from the result. Even the best designs can be diminished, or worse, by poor implementation. An improvement in craftsmanship was a matter of necessity in order for Greene & Greene to realize fully their goal of furnishings as art.

In the year leading up to the Blacker house commission, Greene & Greene created several superb houses in which iconic elements first appeared. The Cole house makes a statement with its porte cochere and boulder chimney. View of southeast corner, Mary E. Cole house, Pasadena, 1906-07.

Graceful and refined, with more than a hint of Chinese influence, this table for the William Bolton house is evidence of another step in the development of Greene & Greene decorative arts. Hall table, c. 1907, William T. Bolton house, Pasadena, 1906.

The quality of work exiting the Halls’ shop was first rate. Joinery is expertly executed, seamless. Pieces are shaped beautifully, giving an organic impression. Surfaces are silky, begging to be touched. Inlays are particularly impressive — incorporating a vast variety of materials from exotic woods to mother-of-pearl, semi-precious stones, copper and silver. Complex designs are masterfully executed. Given that the quality of the furniture and interiors improved significantly when this association began, one can’t help but wonder what course the Greenes’ practice would have taken had fate not brought them together with the Halls. We are fortunate not to know the answer to that question.

The Pitcairn house is a nearly forgotten Greene & Greene gem. Sleeping porches, very deep eaves, an inviting patio and a cantilevered second story are all recognizable features. View of north façade, Robert Pitcairn, Jr. house, Pasadena, 1906.

Following the Robinson commission, Greene & Greene returned, for a while, to designing less grand residences. Homes such as those for Caroline DeForest, William Bolton, John Bentz, John Cole, John Phillips and Robert Pitcairn, all from 1906,23 were substantial, but not on the scale (in size nor scope) of the Robinson. What these homes provided Charles, though he likely didn’t realize it, was an opportunity to further refine his style in preparation for what was to come. The Bolton house is particularly significant in this regard.

The Bolton house was actually the third designed for Dr. William Bolton. The plan included many pieces of furniture in addition to a number of wonderful built-ins. Unfortunately, Bolton died shortly before the house was completed. His widow rented the house to Belle Barlow Bush who continued production of the furniture and commissioned additional pieces from Greene & Greene. The Bolton/Bush pieces demonstrate progress toward the Blacker and Gamble furniture.

It has been well documented that furniture for the Bolton house was the first to include square ebony pegs. While significant, particularly given the importance of this detail in later pieces, it is not the most noteworthy development. The most significant change is, perhaps, less concrete. Bolton/Bush furniture exhibits an elegance and grace of form that is well beyond the brothers’ earlier work. The well-known hall table serves as an example. Lifts on the stretchers are more sculptural and organic than those on previous pieces. A subtle, almost subliminal, arc on the stretchers juxtaposes the primarily rectilinear form. A superb gateleg library table is similarly elegant. The side stretchers and aprons are molded to accommodate the gates when closed. The effect is that of a lift, but in the horizontal plane. It is a fantastic detail that is both functional and stunning. A fern stand includes a form of Greene & Greene finger joints and includes cutouts that presage a Thorsen side table. Pieces in the dining suite are wonderfully unified by use of struts adjacent to the legs. This is an early example of reserving a detail for use in only one room of a house. Dining room furniture also includes inlays that begin a trend of very successful and innovative uses of this design element.

Perhaps the most important legacy of the houses from this era is that they demonstrate the Greenes’ mastery of creating “livable” houses, houses suited to the needs of the occupants and the environment in which they existed. Features such as sleeping porches, great rooms, patios, and 36-inch high kitchen counters all served to enhance the lives of the families who were the firm’s clients. Even careful siting of the structure had a role to play in enhancing the homeowners’ experience. Not all of these characteristics were present in every house, but Greene & Greene developed a repertoire that allowed them to choose appropriately to meet the clients’ practical and aesthetic requirements.

Charles and Henry Greene reached the architectural pinnacle very quickly. The Gamble House appeared only six years after the James Culbertson house. Detail, west façade, David B. Gamble house, Pasadena, 1907-09.

The Legacy Years

By 1907 the Greenes’ synthesized Arts & Crafts/Asian/California style was fully developed. It would evolve still, but more incrementally than during the preceding years. The result is a series of houses known today as the “Ultimate Bungalows.” The Blacker, Ford, Gamble, Pratt and Thorsen houses, all built between 1907 and 1910, constitute an amazing body of work. Designing these homes and hundreds of furnishings in such a short period must have taxed the Greenes’ practice. However, the extreme workload did not detract from the results as it was for these homes that Greene & Greene designed the iconic furniture, and interior and exterior elevations revered today.

What is an Ultimate Bungalow? How do these houses differ from others in the Greene & Greene canon? Merriam-Webster defines a bungalow as, “a house having one-and-a-half stories and usually a front porch.”24 In common usage the term typically implies, in addition, a house of modest size with some built-in cabinetry and generous use of unpainted wood in the interior.25 While some of that definition applies to the Ultimates, these homes are certainly not modest. All are substantial with generously proportioned rooms. Some have entrance halls larger than most modern family rooms. “Ultimate” does not, however, refer only, or even primarily, to size. The materials chosen were the finest available: mahogany, teak, ebony, Port Orford cedar and redwood. The smallest details, such as switch plates and doors, were given significant attention and incorporated into the meta-level design. An overarching artistic vision permeated each project and guided every detail. Thus, in the end, what makes these homes ultimate is that they embody the fully mature vision of a creative genius at his peak.

Much of the last several paragraphs certainly applies not only to the Ultimates but also to the Robinson house. In scale, detail and execution, it is surely on par with the others. Why then is it not a member of the club? There are several possible explanations for exclusion. Clearly, Charles was still, at the time of designing the Robinson, defining his style. The house is in this sense transitional — distinct from that which came before, but not yet completely in the style we associate with Greene & Greene.26 Another possible factor is timing. While the Ultimates were designed more or less consecutively, the Robinson preceded the Blacker, the first Ultimate, by roughly two years.

The term “Ultimate Bungalows” was coined by Randell Makinson and Robert Judson Clark as a way to distinguish the Greenes’ greatest work from the rest of their output. (Makinson no longer favors use of this phrase, thinking it inappropriate.27) At that time, the Robinson was in a state of disrepair. This might also have played a role. Now fully restored, however, the house makes a strong argument on its own behalf. Finally, the Robinson is less “woody” than the others, perhaps less bungalow-like. As we’ve seen, however, none of the Ultimates truly fit the definition of a bungalow. In the end these arguments are unconvincing. With due respect to the well-considered opinions of esteemed members of the Greene & Greene community, the Robinson is included here as an Ultimate Bungalow simply by virtue of the end result.

The Blacker house presents a dramatic visage. This massive porte cochere is one of the best conceived exterior elements on a Greene & Greene house. View of north façade, Robert R. Blacker house, Pasadena, 1907-09.

The Ultimate Bungalows have been widely documented and will be more so later in this volume. There is no need to go into great detail here, though some discussion of the firm’s best work is called for. The Greenes considered the Blacker house to be their masterpiece. Touring the Gamble house can make one somewhat skeptical about this fact. However, even a brief time inside the magnificent Blacker makes clear that the Greenes’ choice was correct. The entry hall and stairway alone could constitute a life’s work. The living room is sheer genius, incorporating many elements yet yielding a result that is soothing with an appearance of simplicity. Barring the privilege of a visit, Randell Makinson’s excellent book dedicated to the house is the best available substitute.28

The only Ultimate to have undergone significant structural changes,29 the Freeman Ford house is an underappreciated gem. Like the Robinson house, it’s exterior is cementious — each of the other Ultimates is clad in wood shakes. Furniture designed for this house is likely less known than that for the other Ultimates, as very little is on public display. One iconic piece, a serving table, is quite well known and on loan to the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens, where it is available for view. Other dining room pieces are as lovely but in private hands.

The Gamble house is surely Greene & Greene’s best-known work. The house remained in the Gamble family from its completion in 1909 until it was donated to the University of Southern California in 1966. For 57 years the house was maintained essentially as built, even the original furniture remained intact save for a couple of minor pieces in the possession of family members. Thus, visitors are able to see the house largely as intended by Charles and Henry. Recall that each piece of Greene & Greene furniture was designed for a particular location. While beautiful when viewed in any context, viewing the pieces in the original setting certainly enhances the experience.

The house for Freeman Ford has been substantially altered. However, the courtyard still invites one outdoors into the California sunshine. View east from courtyard, Freeman A. Ford house, Pasadena, 1906-08.

Built on more than 40 acres in the foothills of the Ojai valley, the Pratt house sits in a more rustic setting than the other Ultimates (or most Greene & Greene houses). Always one to carefully consider siting, Charles was especially attentive in this case, even allowing the site to dictate the footprint of the structure. The resulting obliquely-angled design maximizes mountain views. Furniture for the Pratt house may be the most sophisticated designed by the Greenes. Inlays, in particular, are at another level, beyond any done previously.

Berkeley’s Thorsen house is the last of the Ultimates and the only one outside Southern California. A compact mansion in an urban setting, the Thorsen announces its pedigree with the magnificent clinker brick work visible from the street. Painted friezes in the living and dining rooms are a highlight as is the elegant dining room suite.30 Despite the small lot, the Greenes created a wonderfully private yard through use of an L-shaped plan. Even in this setting they successfully blurred the distinction between indoors and out with numerous windows and patio doors. Even some interior doors are leaded providing an open feel.

From 1905 to 1910 the Greenes designed and oversaw construction of these six masterpieces. The duration of their architectural nirvana was brief indeed. Each project included a substantial house, numerous pieces (in some cases, dozens) of exquisite furniture, lighting fixtures, andirons and fire screens (as well as the fireplaces) and enough fantastic interior woodwork to deplete a rain forest. Architectural trim is given the same careful attention as fine furniture, blurring the line between structure and furnishings. Stairways are especially beautiful perhaps because the Halls had particular expertise in this area.

Furniture designs for the Pratt house, the penultimate Ultimate Bungalow, illustrate the Greene & Greene style at the evolutionary zenith. The whimsical wave motif appears in several forms. Living room armchairs, 1908-11, Charles M. Pratt house, Ojai, 1908-11.

Of course, there were many other jobs moving through the firm during this time including additions or alterations for a number of earlier clients. It’s small wonder then that in 1909 Charles, on whom the bulk of the design work fell, and whose obsessive nature made such a quantity of work doubly difficult, was in need of a break. He took his family to England for an extended stay while Henry oversaw the business. Charles returned later that year resuming work on several of the larger commissions, particularly the Thorsen house in Berkeley. For all practical purposes, however, this was the end of the heyday of Greene & Greene. Charles and Henry Greene had been able to enjoy, if only for a brief time, the artist’s dream of enlightened clients with nearly limitless budgets.

The brothers continued to work together for several more years, most notably on the Mortimer Fleishhacker estate in Woodside, California, and the Cordelia Culbertson house, built by three maiden sisters of James Culbertson on the same Oak Knoll street as the Blacker house, but the firm was winding down. In 1916 Charles moved his family north to Carmel-by-the-Sea. Though Greene & Greene Architects wasn’t officially dissolved until 1922, the brothers worked independently save for some projects for past clients.

After relocating, Charles was mostly content to pursue the life of the Bohemian artist he had always wanted to be. He undertook a handful of new commissions, such as the D.L. James house — a stone masterpiece on the cliffs of Carmel — but was more interested in writing, painting and working on his studio. He was not yet 50 years of age.

Henry remained in Pasadena and continued a solo practice for a number of years. New commissions were much more scarce than during the heyday though he did design a number of houses. He also continued to design additions and alterations for earlier clients. Unfortunately, he was never again able to attain the level of success he and Charles had found in that remarkable period during the first decade of the 20th century. 31

An example of extreme grace, this table combines a perfect form with incredible detailing such as carved scrolls and fantastic inlay. Living-room table, c. 1910, William R. Thorsen house, Berkeley, 1908-10.

Charles Greene’s studio in Carmel may be the ultimate expression of his personality. Note the scrolled brickwork at the upper right. Fence and gate, Charles S. Greene studio, Carmel, 1923-24.

This inglenook represents a career in microcosm. The elements work together in a way that only a genius could have foreseen. Detail, living-room inglenook, David B. Gamble house.