Of England, New York, Japan and California

“Without tradition, art is a flock of sheep without a shepherd. Without innovation, it is a corpse.”

SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL

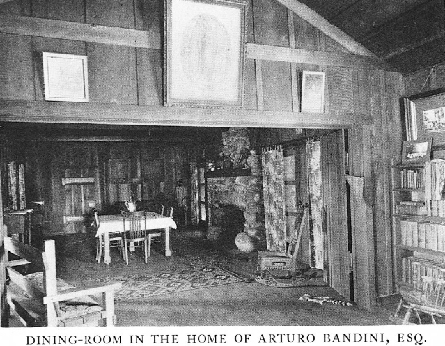

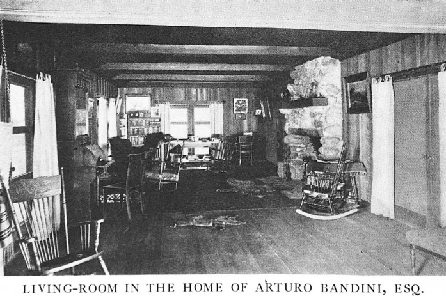

Charles and Henry Greene’s rise to prominence was rapid, their stay at the summit of the architectural world short-lived. The time from the opening of their practice in 1894 until its informal dissolution in 1916 encompassed 22 years, a span remarkable for its brevity. Nearly all of the work for which they are remembered today was created in a period of only about a dozen years. Time, in the short term, was not kind to the Greenes. Their work fell out of fashion and they were largely forgotten. Many of their houses suffered unspeakable abuse ranging from routine “brightening” of interior surfaces to ill-conceived modernization.1 Worst of all, many were simply demolished in the name of progress. We are all poorer for the disappearance of masterpieces such as the Arturo Bandini and Dr. Arthur Libby houses.

Stepping into this room is like stepping back in time. No other Greene & Greene house is as intact. Living room, David B. Gamble house, Pasadena, 1907-09.

By the late 1940s, a small number of architects had begun to rediscover Greene & Greene. Drawn perhaps by the anti-modern (and ante-modern) yet timeless aesthetic, several took it upon themselves to reintroduce the Greenes to a wide audience. L. Morgan Yost, a disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright, was one of the first to reexamine Greene & Greene. He began researching their work at a fortuitous time — both Charles and Henry were still alive and most of their biggest commissions were still intact.2 Henry, in fact, took Yost on a tour of the Blacker house when Mrs. Blacker still lived there. Yost notes, “This was an experience never to be repeated as Mrs. Blacker died the next year, the property was sold, divided and disfigured, and the furniture dispersed.”3 What a thrill it must have been for a residential architect to see that masterpiece through the eyes of one of its creators and his enlightened client, to experience it intact and untouched by the indignities held in its future.

The wood and gold-leaf of the Blacker living room glow in the warm light from the art glass lanterns. Due to furniture by Jim Ipekjian and the hard work of the current owners, the room appears today much as it did 100 years ago. Living room, Robert R. Blacker house, Pasadena, 1907-09.

Yost’s architectural practice was in Chicago. In 1985 he was interviewed by Betty J. Blum for the Chicago Architects Oral History Project.4 In a wide-ranging discussion, over the course of several days, Blum and Yost covered many topics. More than once, the conversation turned to Greene & Greene. When asked what message the Greenes’ work held for him, he replied, “The message of perfection, of course, which is unattainable. They did. If anybody ever attained perfection, they did. They had tremendous ability in form, materials and putting things together. It’s an architecture that has to be seen and felt, including their furniture. They were able at that time to do a house for a wealthy family that would be complete right down to the last table cover and throw, all the furnishings. It was amazing to see such complete perfection.”5

Later, when asked what pre-war (World War II) house he considers most influential, Yost answered, “The residence that influenced me or my work perhaps it’s very difficult to answer because I’ve studied so many and looked at so many built in the last 400 years that I can’t narrow it down particularly. If I had to name any, which is no chore really, I would say the Blacker house by Greene and Greene.”6

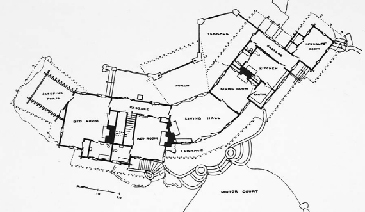

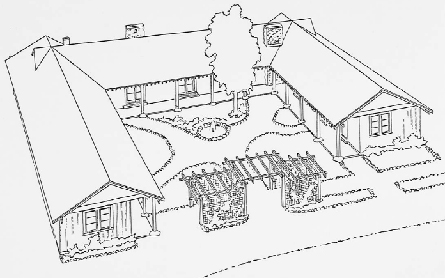

The Pratt house is an exceptional example of the fusion, by Greene & Greene, of varied influences. The California influence is particularly evident. Plan view, Charles M. Pratt house, Ojai, 1908-11.

Perfection is a difficult mistress, perhaps an impossible one as Yost implies. Genius is a heavy mantle. It may be that the short duration of Greene & Greene Architects was inevitable — victims of their own genius and pursuit of perfection. It’s worth noting that Yost’s opinion was not one clouded by the passing of decades and fond recollection. He expressed the same thought in 1950, soon after having encountered the Greenes and their work firsthand: “Every detail was obviously supervised in execution after having been individually designed. These are the most perfect houses, I believe, that have ever been built.”7

One must ask what allowed Greene & Greene to attain the unattainable, to achieve perfection in domestic architecture. Of course, even while asking, it is obvious that there is no clear answer to the question. In the Greenes’ work, as in any masterpiece, there are many elements, both tangible and not, working harmoniously to create a whole that exceeds the sum of its parts. Were it otherwise, were we able to easily dissect and understand creative genius, such inspired works would be commonplace rather than rarities. It is precisely that there is no boilerplate, no recipe to follow, that makes these masterworks the lightning strikes of creative endeavors. Certain artists, however, such as Charles and Henry Greene, appeared able to make lightning strike at will.

Though impossible to reduce to a template, we can identify some of the reasons for their success. Not least among these was their ability to synthesize a new, iconic style by drawing on their training and experience as well as a set of quite varied influences. Architect and historian Clay Lancaster recognized the variety of influence in the development of the California bungalow. “The bungalow movement differed from earlier revivals in the indefiniteness of its source of inspiration, which allowed the architect’s imagination free play, thereby sanctioning originality in a roundabout way.”8

This is, perhaps, the great triumph of their careers — the sensitive fusion of elements of the Arts & Crafts movement, an Asian aesthetic and the requirements of their adopted California in a way to appear entirely rational and natural, even inevitable. Of course, it was anything but inevitable at the dawn of the 20th century. Only a visionary could have anticipated the result of this integration; of incorporating such seemingly disparate aesthetics.

Arts & Crafts

Viewed through the lens of more than a century, the Victorian era can seem rather quaint. Popular perception is of a time of extreme formality, fussy ornamentation and a strict moral code. It was also a time, however, in which prostitution and child labor were rampant, social classes were rigid (leaving many in abject poverty) and technology, in the form of the industrial revolution, was changing the nature of work for many.

It is against this backdrop, indeed in response to it, that the Arts & Crafts movement was born. A reaction against elements of the Victorian world, the Arts & Crafts movement was much more than a simple design philosophy; it was a social movement. Early proponents in England, such as John Ruskin and William Morris, were social philosophers, in point of fact, socialist philosophers. They encouraged a return to craft rather than a continued move toward assembly, arguing that it dehumanizes a man to repeatedly perform the same task rather than to create an object, such as a piece of furniture, from beginning to end.

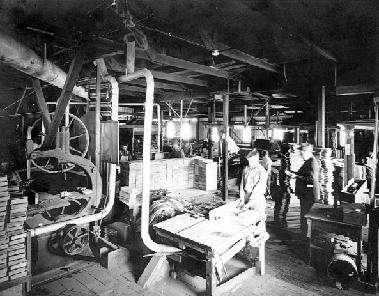

If Greene & Greene did, in fact, attain perfection, it was due in no small part to Peter and John Hall. Their alliance was essential to the Greenes’ legacy. Peter Hall transitioned to making boxes for fruit and candy companies when work for Greene & Greene decreased.

It is noteworthy that Charles and Henry Greene were not social philosophers. They did not publicly advocate social or political change. One can only speculate as to the reason but one rational candidate is that there was little need. In England, Ruskin and Morris had a well established society against which to rebel, an established hierarchical class structure to overthrow. In California, the ultimate land of opportunity, on the other hand, the Greenes were not presented with this tempting target for reform. There a man, any man, could make his way and hope, with some reason, to be successful. Charles Greene himself addressed this notion in a 1905 article: “California, with its climate, so wonderful in possibility, is only beginning to be dreamed of, hardly thought of yet.”9

Ruskin, Morris and other founders of the movement also railed against overly ornate Victorian design with excessively applied decorative flourishes, often poorly constructed. They argued instead for far simpler, more functional designs, honestly made so that construction details were often apparent, as with exposed joinery.

Thus, the Arts & Crafts movement had two primary goals: the improvement of working conditions, particularly for those employed in the manufacture of goods; and a fundamental change in the style and utility of objects people would choose to have in their homes. Indeed, it was hoped that there could be improvement in what people perceived as beautiful.10 There was some success on both fronts, at least for a time. However, even many of those closely associated with the movement were not in lockstep. This was a big tent with many proponents holding views at varied points along a broad spectrum.

Aesthetic differences among individuals with common philosophies are not surprising. That a Frank Lloyd Wright chair differs from one by Charles Rennie Mackintosh is, in fact, to be expected. Highly creative artists will always try to distinguish themselves. What may be more surprising, given the emphasis by the originators of the movement on a return to artisanship, is the degree to which followers disagreed on the use of machinery in production.

To fully understand the place of the machine in the Arts & Crafts movement, one must first understand the manufacturing practices of the time. While it is true that the industrial revolution brought about a dramatic increase in the use of machinery in the manufacture of goods, another complementary development was likely more troubling because it was more dehumanizing. That development was the increased use of assembly lines.

There is a correlation between increased reliance on machines and increased use of assembly lines. However, the former does not necessitate the latter.

The assembly line (not to be confused with the moving assembly line) had been in use, in some form, for centuries. The result of assembly line use is an increase in repetitive tasks by the worker and a concomitant decreased role in the artistic creative process. This is the dehumanization the founders of the movement sought to eliminate. To be sure, machinery played a role as well, particularly in those cases in which the worker was reduced to a mere machine operator.

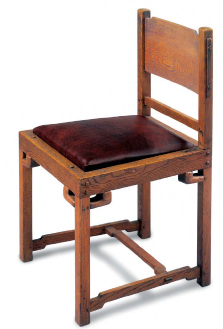

This chair from the Tichenor house is not very well constructed, but the design includes lifts and brackets that are recognizable to any fan of Greene & Greene. Desk chair, 1904-05, Adelaide M. Tichenor house, Long Beach, 1904-05.

Many proponents of Arts & Crafts sought a true return to the pre-Renaissance guild system, complete with a total lack of machinery. However well-intentioned, this absolutist viewpoint was largely unrealistic. Social economist Thorstein Veblen addressed this point, “Therefore, any movement for the reform of industrial art or the inculcation of aesthetic ideals must fall into line with the technological exigencies of the machine process, unless it choose to hang as an anemic fad upon the fringe of modern industry.”11

Between these two extreme views, one finds many practitioners, those who, unlike the academics and socially-minded wealthy, made their living producing goods for public consumption. Forced perhaps, as Veblen suggests, to be practical, they may adopt modern machinery where necessary. Certainly this is the case for many producers of Arts & Crafts furniture in the United States. Even William Morris was willing to use machines “to relieve drudgery” provided that the product did not suffer.12

Peter Hall was sympathetic to this view. In his shop one would find many machines to increase efficiency and relieve drudgery. One would also find, however, numerous benches at which artisans performed handwork of great finesse and high quality. This form of woodworking will be familiar to many modern woodworkers who recognize the utility of both hand tools and machines. Why spend time setting up a machine to perform an operation when a few swipes with a hand plane will do the job? Conversely, why spend hours dimensioning a stack of lumber by hand when machines can do it in a fraction of the time?

This eminently reasonable approach is entirely consistent with the Arts & Crafts philosophy. Ernest Batchelder is today most famous for his beautiful decorative tiles. During the first decade of the 20th century, however, he was a well-known and respected designer and educator. From 1902 until 1909 he taught design theory and manual arts at Pasadena’s Throop Polytechnic Institute (precursor to the current California Institute of Technology). Batchelder addressed the point at hand quite eloquently, arguing that the use of machines is not inherently immoral: “The evil of machinery is largely a question of whether machinery shall use men or men shall use machinery.”13

An important aspect of the Arts & Crafts philosophy is the unification of mental and manual processes. While traditional academic study was seen as critically important, the view was that it should not be to the exclusion of manual abilities such as wood and metalworking. A proper balance was seen as necessary for the development of a man. Charles Robert Ashbee, founder of Britain’s Guild and School of Handicraft (1888), saw the man as the end product: “The real thing is the life; and it doesn’t matter so very much if their metalwork is second rate.”14

This same view was the genesis of the Manual Training Movement that spread through the United States in the second half of the 19th century. Charles and Henry Greene attended the Manual Training School of Washington University where they gained experience in the use of both hand tools and machinery. Similarly, William Morris “learned to dye, weave, embroider, and print in order to design for the peculiarities of each craft.”15 Ashbee included a manual training school in his guild after he relocated to Chipping Campden and transformed it into a Utopian colony. In this way, part of the Craftsman ideal was introduced to segments of the public who may have been unaware of Arts & Crafts or, perhaps, knew it only as a style of furniture.

In the spring of 1901, Charles Greene married Alice White, formerly of England, and the couple departed for a honeymoon of several months in Europe, where they visited both the Continent and Great Britain. Charles and Henry had been aware of the Arts & Crafts movement prior to this time, but Charles’ time in England and Scotland clearly had an impact. There Charles would have had the opportunity to see work by leaders of the movement such as C.F.A. Voysey, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and M.H. Baillie Scott. It is not known precisely which works Charles did or did not see. What is known is that soon after his return Greene & Greene designs began to change rapidly.16

In America, Gustav Stickley is all but synonymous with Arts & Crafts. While he is best remembered today for his furniture designs, he was also a publisher. His magazine, The Craftsman, gave him a forum for expressing his ideas and spreading the Arts & Crafts gospel. While it also gave him a vehicle for selling his furniture, Stickley published his furniture plans in The Craftsman so that anyone could, with Stickley’s explicit encouragement, implement his designs themselves. Rehumanization for the masses through woodworking.

Stickley was, for a while, quite successful. His designs and manufactured furniture were ubiquitous and often copied. His shop (or was it a factory?) churned out many pieces of Mission-style furniture that are coveted today. Typically quite spartan, even severe, they were true to the principles of the movement, particularly as practiced in America: wonderfully straightforward and well constructed.

A house should be one with its environment rather than simply sit on it. No Greene & Greene house adheres to this principle more fully than for Walter Richardson. Adobe and rocks are from the site, giving the impression that the house grows out of the ground. Detail, west façade, Walter L. Richardson house, Porterville, 1929.

In a brief essay, entitled “An Argument for Simplicity in Household Furnishings,” in the first issue of The Craftsman, Stickley articulates the Arts & Crafts approach to design. “In all that concerns household furnishings and decoration, present tendencies are toward a simplicity unknown in the past. The form of any object is made to express the structural idea directly, frankly, often almost with baldness. The materials employed are chosen no longer solely for their intrinsic value, but with a great consideration for their potential beauty.”17 He later adds, “We are no longer tortured by exaggerated lines the reasons for which are past divining … We are, first of all, met by plain shapes which not only declare, but emphasize their purpose.”18

The Stickley display at the Buffalo Pan-American Exposition in 1901. Charles and Alice Greene visited on their return trip from a European honeymoon.

Greene & Greene certainly shared this view though whether that was the case before reading Stickley is difficult to determine. For an article in the Pasadena Daily News, Charles wrote, “Consciously or unconsciously we admire things that are true to themselves…”19 This is a concise statement of the same principle: that objects should be well designed, suit their purpose and be constructed with sensitivity to the materials used. This sense of honesty or integrity was perhaps the dominant theme of Arts & Crafts designs since there was no definable style, no rulebook for determining the Arts & Crafts pedigree of a piece.

In practice, this led to an interesting conclusion: that construction details could themselves serve a decorative purpose. We see this in the carefully wedged or pegged joints in furniture of the period. We see it in the beautifully expressed post-and-beam construction in the homes. We see it in the attention paid to finishing wood in a way that enhances, rather than hides, its grain and natural character. Wood was sometimes abraded with a wire brush to make the grain more visible, a more prominent part of the design. “No ceiling ornament can equal the charm of visible floor joists and girders, or of the rafters. They are not there merely to break up the monotony of a flat surface, but primarily to keep the upper stories from falling on our heads. Incidentally, they are a most effective decoration with their parallel lines and shadows.”20

Charles and Henry Greene were not the only architects working in Pasadena to hold views in accord with this philosophy. At least one wrote about these ideas quite eloquently. Elmer Grey demonstrated his sensitivity, “…all commoner forms of deception that would disguise the natural expression of a building’s character are immediately discernible as defects in style.”21 The Greenes were quite successful in applying this principle in their work. Such judgments were made contemporaneously by critics. “…and above all things to have all construction and materials true to their own nature, believing that brick treated simply as brick, stone as stone or wood as wood, is better than any disguise that can be put upon them.”22

In addition to using materials in a way sympathetic to their character, there was a desire to use, to the extent possible, local materials. The argument is that a house should not sit on the landscape but rather should be a part of the landscape. Use of locally sourced materials, or even better, materials from the home site, certainly helps accomplish this. Greene & Greene practiced this often. A number of their homes along the arroyo include arroyo stones in the construction, appearing in fireplaces, chimneys, retaining walls, etc. In one particularly interesting case, the bricks used in construction of the Richardson house in Porterville were made by hand on site from clay derived on site. Many other materials, mahogany for example, were not local but Greene & Greene clearly demonstrated their commitment to this principle in significant ways.

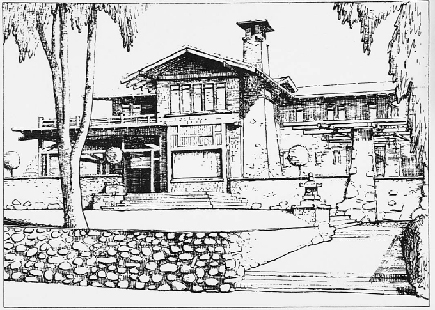

In the Irwin house we see evidence of all of the significant influences on Greene & Greene: Arts & Crafts, Asia and California. Sketch of west façade, Theodore Irwin, Jr. house, Pasadena, 1906-07.

In America, Gustav Stickley was the public face of Arts & Crafts. Charles saw Stickley’s furniture in 1901 during the return trip from his European honeymoon when he and Alice visited the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. There Stickley displayed his line of United Crafts furniture.23 This was the first significant exposure for pieces that would soon become part of the public consciousness. The first issue of The Craftsman appeared later that year. Charles and Henry were readers from very early on.

Arroyo boulders, carefully placed, make the chimney the dominant feature of the Cole house. Detail, south façade, Mary E. Cole house, Pasadena, 1906-07.

Viewing the well-known designs of the mature Greene & Greene style, it can be difficult to believe that Stickley’s work influenced them. The Greenes never publicly promoted the political ideals of the movement nor did they adhere as strictly to the design tenets. Their pieces appear lighter, more graceful than most Arts & Crafts pieces, particularly Stickley’s, with significantly more ornamentation. We know, however, that Stickley was an influence as Charles’ notebook is littered with clippings from The Craftsman. Charles frequently suggested Stickley pieces to furnish homes for which he did not design furniture. Ultimately though, the Arts & Crafts influence was merely a point of departure, a genesis that the Greenes would use in the synthesis of their own style.

Simple, natural beauty is integral to the concept of shibusa. The garden is as necessary as any other part of the home.

The Call of the East

Perhaps no culture has codified aesthetics as thoroughly as the Japanese. In Japan, no object is considered too trivial to be made beautiful. Beauty is essential, as necessary as food and shelter. It is integral to the Japanese psyche.24 Such thinking goes well beyond mere stylistic conventions, which are numerous. It extends to material selection and methods of construction. It is a nearly religious devotion to not only the final result but to the practices employed as well. The ends do not justify the means. The means are, in fact, an end unto themselves. The journey is as important as the destination.

Recall the famous quote by William Morris, discussed in Chapter 1, “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” Perhaps the best-known quote to arise from the Arts & Crafts movement, this seems to share the Japanese sentiment regarding beauty. However, on closer inspection, we see that Morris was not sufficiently restrictive to rise to the level of the Japanese aesthetic. In Japan, Morris’ “or” would be replaced with “and” so that only useful objects that were also beautiful would meet the standard. This distinction is significant and helps emphasize the place of beauty in Japanese culture. The work of Greene & Greene, particularly during the height of their careers, is certainly more in line with the Japanese view. To repeat the quote from Charles Greene, it was their goal, “…to make these necessary and useful things pleasurable.”

Such an attitude inevitably leads to a quest for perfection. In this regard, the Japanese may have surpassed all other cultures. In Japan, artistic traditions persist for centuries, their forms and practices refined and codified. Think of the formal tea ceremony or haiku. Each is a rather mundane concept elevated to high art by an insistence on perfection. In his seminal work Impressions of Japanese Architecture, architect Ralph Adams Cram addresses this point: “In a way, Greek and Japanese art are closely akin: each represents the exquisite perfecting in every minutest detail of a primary conception neither notably exalted nor highly evolved, yet the result is, in plain words, final perfection.” He notes that in the West this does not occur, as Westerners move on to new art forms of the day: “…each was supreme as a radiant, almost divine conception, but none, not even thirteenth century Gothic, nor fifteenth century Italian painting, was suffered to develop to its highest point: each was abandoned when hardly more than sketched in…”25

A relevant illustration of this Japanese viewpoint comes from an 11th century book on gardening. Sakuteiki, written by a Japanese court noble, is the earliest known book to describe Japanese garden design principles. Discussing the use of stones in landscape, the author writes, “The placement of the stone must follow the stone’s request.”26 Thus, synthesis of method and design has a long history in Japan, a country in which history is revered. This quote also reveals another aspect of Japanese design — sensitivity to materials.

It seems natural in a society that codifies and adheres to principle to such a high degree that particular attention is paid to use of materials. Wood is an exceptionally important material and is treated with a respect, a reverence, quite uncommon in the West. A Japanese woodworker is much more in tune with the material than most of his Western counterparts. This is partly a cultural phenomenon but also likely stems in part from the way in which the Japanese woodworker interacts with the material, which is quite intimately given the nature of the low benches used. The attention is not limited to wood, however, as all of the materials used in architecture are treated with respect. Writing of Japanese buildings in House Beautiful, author Curtis Besinger writes, “The beauty of their buildup depends to a great degree upon the materials used and the thoughtful and careful manner in which they are put together.”27

Charles Greene’s admiration of Japanese architecture is evident in Greene & Greene designs after 1903, though the effect is often not literal.

One obvious application of this principle is the use of materials appropriate to their intended purpose. This is a crucial, and long recognized, aspect of Greene & Greene architecture, “…it is beautiful, it is contemporary, and for some reason or other it seems to fit California. Structurally it is a blessing; only too often the exigencies of our assumed precedents lead us into the wide and easy road of structural duplicity, but in this sort of thing there is only an honesty that is sometimes almost brazen. It is a wooden style built woodenly, and it has the force and integrity of Japanese architecture.”28 Perhaps as apt a description of the idiomatic Greene & Greene style as exists, “a wooden style built woodenly” and “an honesty that is sometimes almost brazen” are high praise from Ralph Adams Cram who was something of an idealist.

A less obvious interpretation, though one that is no less important in an analysis of Greene & Greene commissions, derives from the extreme attention to detail required to solicit a stone’s intent when placing it in a design. Charles Greene’s propensity for very direct involvement in the implementation of his designs is well-known. In some cases Charles insisted that workers dismantle portions of projects and redo them, possibly under his direct supervision. Charles is said to have chosen stones for placement, presumably at the stone’s request. He understood that stones and bricks could not be placed at random, that sometimes the decision belongs to the material.

That the Greenes, Charles in particular, were influenced by Japan is indisputable. One must be careful, however, not to be overly aggressive, not to confuse merely sympathetic philosophies with influence. That two events occur does not establish a causal relationship. There are many features present in both Japanese art and architecture and the work of Greene & Greene, and there are many concepts that apply well to both. Given that the Japanese work and concepts predate Greene & Greene, often by many centuries, it is tempting to conclude that direct influence occurred. While we know some of the venues by which Charles and Henry encountered Japanese forms, there is also much that we do not know. Charles was likely drawn to Japanese designs when he encountered them because they resonated with something innate within him. It is possible, even probable, that he developed some detail, or designed in sympathy with an Eastern design philosophy, without having encountered the original. We should not, however, allow this fact to quell our curiosity or prevent us from investigating the similarities and wondering about the degree to which Japan is responsible.

The server from the Ford dining room is both simple and dramatic. The overhangs at each end mirror the broad eaves of the firm’s architecture. Dining room server, c. 1908, Freeman A. Ford house, Pasadena, 1906-08.

Closer inspection of the Ford server reveals subtle details. The legs are slightly concave, lightening the look. The lift on the upper rail is actually an unusual, more complex segmented shape than is typical. Detail, dining-room server, c. 1908, Freeman A. Ford house.

In Japanese there is a term that expresses the ultimate in beautiful design: shibusa (shibusa is the noun form while shibui is the adjectival form). Not surprisingly, it is a term that doesn’t translate uniquely or easily as attested to by the broad range of English definitions. Described variously as calm understatement;29 quiet, sober refinement;30 severe exquisiteness;31 and interesting beauty,32 it is an important concept in Japanese aesthetics for it is intrinsically Japanese.

Scrolls are a theme in the Blacker house entry. They appear on beams and on numerous pieces of furniture. Note the two distinct scroll forms in this scene. Detail, stair, Robert R. Blacker house.

The August 1960 issue of House Beautiful was devoted to an introduction to and examination of shi-busa. In one brief article, the editors consider the idea of beauty in Japan. They present a hierarchy of four terms and definitions that shed light on the concept in Japanese culture. The terms are Hade, Iki, Jimi and Shibui.33 The list is presented in order by increasing level of sophistication and decreasing level of ostentation with shibui described as the essence of Japanese culture and the ultimate in taste.34 While neither description does much to fix the meaning for one not already familiar, they do underscore the importance of the concept in analysis of Japanese art and architecture (“art” is used here in the broadest sense).

Fortunately, more descriptive definitions are available to help those without the intuitive grasp that can be achieved only through immersion. Jiro Harada wrote, “It is that quality which is quiet and subdued. It is natural and has depth, but avoids being too apparent, or ostentatious. It is simple without being crude, austere without being severe. It is that refinement that gives spiritual joy.”35

There is no evidence that Charles or Henry Greene were familiar with the concept of shibusa. It does not, for example, appear in Edward Morse’s Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings, a book Charles Greene owned. It is possible that they had encountered it; however, what seems more likely is that they understood the idea, were sympathetic to the view, without having been exposed to it. While we may never be able to know, one thing of which we can be certain is that much of the work of Greene & Greene is shibui. When viewing the server from the Freeman Ford house or the dining table from the Gamble house, phrases such as, “simple without being crude, austere without being severe” certainly come to mind. The entire Blacker house is a study in “refinement that gives spiritual joy.” Thus, whether Greene & Greene were actually influenced by knowledge of shibusa is a moot point, for their work demonstrates a sensitivity to the concept and, by extension, to Japanese aesthetics.

The Japanese Pavilion at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (the 1904 World’s Fair) in St. Louis was a source of inspiration for Charles Greene.

While Greene & Greene are not mentioned in any of the numerous articles in the House Beautiful shibusa issue, several contain passages that describe their work quite aptly (these passages also apply very well to the work of others, of course). One example, that seems particularly relevant to the Greenes’ commissions after 1905, addresses integrated design: “The most notable thing is the serenity of the houses, the gardens and the domestic works of art. This characteristic is quite frequently mistaken for simplicity or denial. But upon deeper analysis, it clearly stems from a highly controlled, highly developed complexity. The illusion of simplicity comes from the fact that they have put their development effort where it will count most: the making of an integrated whole.”36

Integrated design is also a familiar theme in the Arts & Crafts movement. This is but one example of values common to both Japanese design philosophies and the Arts & Crafts movement. As discussed above, a strong interest in, or even devotion to, the selection and use of materials was a key element in both schools of thought. While there is no notion similar to shibusa in Europe or the United States, Arts & Crafts designers typically strove for a level of simplicity and commonly used themes from nature, both of which are shibui attributes. Further, elements drawn from nature were often used in highly stylized form as in the Japanese/Chinese cloud scrolls37 and mist symbol and in many Stickley inlays as well as those in much of the furniture in the Blacker house. Finally, in both philosophies, there is a deep respect, perhaps a reverence, for labor and the process of creation. While more formal in Japan, this idea was one of the cornerstones for the founders of Arts & Crafts in England. This should not be surprising since in England this was seen as a return to the medieval guild system while in Japan there was no need for a return as the system had changed very little over time.

One needn’t have formal training in design to detect Asian elements in the work of Greene & Greene. They are numerous, as are the sources from which the Greenes may have borrowed them. One of the best known examples occurred during their trip west to California in 1893 when Charles and Henry made a detour to Chicago, host of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Physically the largest world’s fair to that time (and second in attendance only to the 1889 Paris International Exposition), the Expo consisted of 630 acres of science, technology, amusements and architecture.38 Most of the architecture, particularly on the central Midway, was in the classical style. However, the grounds also included a large number of other buildings, contributed by U.S. states and other countries. The styles of these outlying buildings varied greatly from the uniformity found in the Midway.

Much has been made of the Columbian Exposition as a pivotal event for the Greenes, particularly with respect to the influence of the Ho-o-den Japanese exhibit. However, as Greene & Greene scholar Bruce Smith argues, there was no significant incorporation of Japanese elements in their work for about a decade after the Columbian Exposition.39 This makes a compelling case that there were other, more seminal, Asian influences. One such influence came to the Greenes courtesy of a determined, perhaps strong-willed, client.

Most architect-client relationships are rather one-sided. While the architect may take cues from the client, the flow of real ideas is largely unidirectional. Once in a while a fortunate architect might find a special client who pushes them to new places, encourages them to expand, to experiment with new ideas. The Greenes found such a client in Adelaide Tichenor. In 1904, prior to the design of her house,40 Mrs. Tichenor attended the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. So struck was she by what she saw that she wrote Charles imploring him to travel immediately to St. Louis. “… the more I see of it, the more I feel that I do not want to go on with my home until you see it.” She continued several lines later, “I really think that you will never regret it if you arrange your affairs to come at once. I think it must be as hard for you to leave one time as another — and you will be able to get so many ideas of woods and other things for finishing what you now have on.”41

Despite a heavy workload, Charles did journey to St. Louis, persuaded not only by his very insistent client but also by a desire to see the firm’s, and his own, entries in the architectural exhibits at the fair. What Charles saw at the fair, the display that had so excited his client, was the impressive Japanese Pavilion. Consisting of eight buildings and surrounding gardens, the Japanese exhibit provided a significant and authentic view of both temple and imperial architecture.42 The gardens and Main Hall, a scaled near-replica of the Shishin-den,43 sometimes described as the heart of Kyoto’s Imperial Palace, particularly appear to have impacted Charles. Though some Japanese forms had emerged in the firm’s work previously, the trend accelerated from 1904 onward.

The Van Rossem house (the first of three) is the site of an amazing clinker brick wall. This gate, with Chinese tiles, clearly shows the Asian influence on the Greenes’ work. Detail, wall and north façade, Josephine Van Rossem house #1, Pasadena, 1903.

While visits to the 1893 and 1904 World’s Fairs were undoubtedly significant, one must be careful to place them in proper context. Both Greenes had been exposed to Japanese forms prior to 1904 while in Boston. Beginning in the late 1870s and through the 1880s, Boston was in the grip of a craze of Japonism. At the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Japan had ignited the public’s imagination with the first display of (supposedly) authentic Japanese forms in the United States. During this time, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston prominently featured their large collection of Japanese and Chinese objects. Charles and Henry almost certainly viewed the collection as students at MIT were granted free access to the museum.44

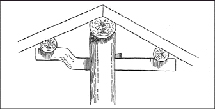

Charles Greene owned a copy of Edward Morse’s Japanese Homes and their Surroundings, likely his source for the practice of setting posts on stones or rocks.

Morse depicted and described many aspects of the Japanese house. In some cases, the influence of the images on Greene & Greene was indirect.

Though first used by Greene & Greene in the house for Arturo Bandini, the firm often returned to the practice of setting posts on stones. View of courtyard, Cora C. Hollister house, Hollywood, 1904-05.

Even without leaving Pasadena, Charles and Henry Greene had access to decorative objects from the Orient courtesy of client John Bentz. Charles and Henry visited, and patronized, the shop regularly.45 In addition, Charles owned a copy of Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings by Edward S. Morse. In this book, Morse gives a detailed, firsthand account of Japanese residential architecture in the mid-19th century. Thus, Charles was ready for a move toward increased use of Japanese themes. Perhaps the most noteworthy aspect then of his trip to St. Louis was that he knew he had found a client eager to help him make that move.

In some cases the Japanese influence in Greene & Greene designs is obvious. The exposed timber construction in their houses is also common in Japanese architecture, particularly Imperial buildings and temples.46 For the Arturo Bandini house (1903), Charles borrowed another traditional Japanese form. Posts, supporting the roof over the broad walkway around the perimeter of the courtyard that forms the focal point of that house, rest on carefully placed stones as in the Japanese idiom.47 Though the effect is not overtly Asian in the context of the rustic Bandini house, the influence is plain to see. Broad eaves, a standard feature on the firm’s houses, beginning around the time of the Culbertson house, are another Japanese form (a detail mirrored in wide overhangs on furniture — recall the discussion of integrated design).

Less known examples abound as well. One is the scroll detail — a Chinese element — best known for its use in the Blacker house. In that house, the scroll is omnipresent in the entry hall furniture. It also appears in both interior and exterior architectural details. Sometimes called “cloud scrolls” in Chinese design,48 the Greenes also used this detail more subtly. One instance is at the base of the stairs in the Gamble house, as well as in some Gamble furniture. Another is in the carvings on the legs of the beautiful Thorsen living room table. Scrolls also appear throughout the exquisite Robinson house. Sometimes nearly hidden, seeking the scrolls there makes for something of a sport, for those obsessed with such things.

The cloud form is nearly ubiquitous in Chinese furniture for a period of nearly 2,000 years. The shape and meanings evolved through the dynasties from the Han (roughly 200 BC to 200 AD) to the Qing (into the 20th century). Author Sarah Handler writes: “As far back as the Han dynasty, clouds are depicted as long scrolling lines with curled flourishes, which sometimes resemble birds’ heads or dragons’ claws and are thus endowed with animistic powers. They are associated with the life-giving power of rain and were vehicles on which the immortals rode above the earth. In the Tang dynasty billowing clouds with lobed heads were added to the repertoire. Song dynasty furniture often had cloud-shaped leg flanges and cloud-shaped feet… During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The motif came to symbolize many blessings, particularly good fortune and long life.”49 Given Charles’ affinity for Eastern philosophies, it seems likely that he was aware of the symbolism.

Chinese cloud scrolls appear in a number of Greene & Greene houses including the Blacker, Gamble and Robinson. In the Robinson house they are scattered throughout the house and are sometimes subtle, as in this chandelier. Hall chandelier, 1906-07, Laurabelle A. Robinson house, Pasadena, 1905-06.

While one often reads of Japanese influence in the work of Greene & Greene, the Chinese influence is sometimes overlooked. One possible reason for this is that it can be difficult to distinguish the two. Many aspects of Japanese culture can be traced to China, though only by traveling through many centuries of history. That is not to say that the sources are interchangeable — after appearing in Japan the forms followed independent evolutionary paths in the two countries. The most commonly made distinction is that the Greenes were influenced by Japanese architecture and Chinese furniture. While likely a simplification, there is enough truth in that statement to allow it to stand as a reasonable explanation.

The chairs for the Robinson dining room are heavily influenced by Chinese furniture. The concave crest rail and arms are particularly obvious. Dining-room armchair, 1906-07, Laurabelle A. Robinson house.

Designed by Henry Greene and built on a working citrus ranch, the Richardson house is in a setting unlike any other in the Greene & Greene canon. View to the north, Walter L. Richardson house.

Chinese furniture is viewed as small-scale architecture. Sarah Handler: “Each piece of furniture is a form of architecture in miniature with walls, joinery, and an implicit duty to serve human activity. Each example is made from wood, has a rhythm in its harmonious parts, and is an act of beauty by its presence. The architecture of furniture fits into and lives within the architecture of the building. The two art forms grace and enhance each other.”50 In Chinese, the words for building framing (da muzuo, or large carpentry) and furniture making (xiao muzuo, or small carpentry) are quite similar, further illustrating the connection between structures and furniture. This is a similar concept to the Greene & Greene approach of creating furniture and interior woodwork that is in harmony with the overall structure of the house.51

California: A New Land

Both the Arts & Crafts movement and Asian forms clearly affected the Greenes, particularly Charles. Another seminal influence, however, may have superseded England and Japan: California. With its unique climate, and topography, Southern California suggested, perhaps even imposed, a lifestyle. It was the Southern California lifestyle that captured the imagination of the country. It was the Southern California lifestyle that lured the wealthy to Pasadena. Ultimately, it was the Southern California lifestyle that dictated the fundamentals of the California Bungalow developed by Greene & Greene.

M.H. Baillie Scott wrote, “The most reasonable basis from which to start in furnishing is obviously the actual practical requirements of the particular fam-ily…”52 Charles Greene shared that sentiment writing, “The style of a house should be as far as possible determined by four conditions: First — Climate. Second — Environment. Third — Kinds of materials available. Fourth — Habits and tastes i.e., life of the owner.”53 California puts its imprint on each of these factors. The dry warm climate, with several hundred days of sunshine annually, requires that the design protect the interior from heat caused by direct sunlight, hence broadly overhanging eaves and sleeping porches. The Greenes were masters of using local materials such as arroyo boulders in walls and foundations. California clearly influenced the habits of the firm’s clients, many of whom were Midwesterners seeking the Southern California lifestyle, including escape from the months-long incarceration imposed by harsh Midwestern winters. The Greenes responded with residences that blur the distinction between inside and out, allowing seamless movement between the two.

This idea was neither new nor particularly Western. Chinese-born American architect I.M. Pei has expressed it this way: “The indoors and outdoors are always one … A study for a scholar without a small garden in front of it is not a study. You have to talk of the two as one.”54 Pei implies a total interdependence between indoors and out. Perhaps more philosophical than practical, his approach, common in China and Japan, is one with which the Greenes were entirely sympathetic.

That clients of the firm would desire outdoor living is little surprise. Aside from the ideal Pasadena climate they were seduced by the arroyo seco, bordering Pasadena to the West, near which many of their houses were built. In the August 1912 issue of The Craftsman, devoted to the American West (which is to say, California), an article entitled “Parks for the People” waxes poetic about the arroyo.

“In winter and spring, the seasons of rain in the Southwest, and the time when the snow is melting and flowing down from the mountain tops, the stream widens into a broad rushing torrent that tugs at the boulders and tree trunks on the banks. In the upper end of the Arroyo the stream-bed holds water the year round, and trout are found in the deeper quiet places; but on the lower levels summer finds the path of the stream empty, huge boulders and small stones gleaming white and clean from their winter flood polishing. In winter, spring and early summer there are luxuriant beds of wild ferns of many varieties hiding in shadow of trees and crags, or delicate maidenhair and fluffy mosses cling to precipitous rock walls, and the wild-flower beds are radiant with Nature’s loveliest offerings of color, perfume and flower textures.”55

Another successful use of the U-shaped form, the Richardson house courtyard provides an oasis in the arid Central Valley Summer landscape. Detail, west side of courtyard, Walter L. Richardson house.

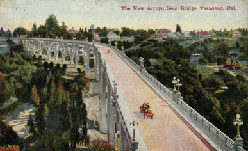

The arroyo seco played a significant role in the development and life of Pasadena. Rather than destroying the landscape, the beautiful Colorado Street Bridge (1913) became a man-made highlight.

The arroyo was far more than simply a beautiful natural resource, it provided the basis for a sub-culture quite distinct from the more traditionally formal society of the wealthy whose houses lined Orange Grove Avenue. The arroyo culture was an Arts & Crafts culture, one steeped in the traditions of Morris and Stickley. Alice Batchelder, wife of Ernest Batchelder of tile-making fame, described the culture this way: “The house, the home, music, art, self-expression, love, understanding, and work blended in a manner to create a complete, well-rounded pattern of living.”56 It was a culture centered on an informal moral code tied to nature, learning, handwork, artistry and local materials. Fifty years later it might have taken the form of a commune had anyone with such intentions at that time the means to afford real estate in that rarified location.

Though a largely informal group of similarly minded individuals, there was some degree of organization in the form of several people who strongly espoused the lifestyle. Much of what we know today about the arroyoans is due to Southern California’s proselytizer-in-chief, Charles Fletcher Lummis, who through his magazine Land of Sunshine (later Out West ) promoted arroyo culture in particular and the Arts & Crafts philosophy in general. No mere snake oil salesman, Lummis lived the life as well. His own home on the arroyo was a meeting place for intellectuals and the artistically inclined. That home, built largely by Lummis with additional labor provided by local Native Americans, was a 13-room, arroyo-boulder-clad testament to the Southwestern traditions Lummis so loved. Any advocate of the American Arts & Crafts movement would certainly have felt at home there as well.57

Another important figure in promoting the arroyo culture was George Wharton James whose very short-lived journal The Arroyo Craftsman (only one issue was published, in October 1909) was intended as the voice of the Arroyo Guild of Craftsmen. James wrote repeatedly about the arroyo for Stickley’s The Craftsman, where he was an associate editor. Little is known about the Guild except that its purpose appears to have been to provide homes designed and fully furnished in the Arts & Crafts manner.58 The membership is, unfortunately, not known. Nor do we know if Greene & Greene were involved with the Guild. It seems unlikely that they would have been actively involved at the time that The Arroyo Craftsman appeared due to the volume of work in their office and Charles Greene’s decreasing interest in the full-time practice of architecture.

In an article he wrote in 1908, Charles Greene describes Arroyo Terrace, a street perched above the arroyo offering inspiring views. A street that by that time included half a dozen Greene & Greene homes including Charles’ own. “From one side of the street the land drops steeply. The slope is covered with live oaks down to the valley below, and in the distance in one broad view rise the mountains. It is unlikely that this land will ever be built upon, — probably it will be a park.” 59 The arroyo had more important proponents than the Greenes. During a 1903 visit to Pasadena, President Theodore Roosevelt, known for his outdoorsman tendencies, spoke glowingly of the arroyo: “What a splendid natural park you have right here! O, Mr. Mayor, don’t let them spoil that! Keep it just as it is!”60 He reiterated his admiration in a post-presidential visit in 1911. At that time, he remarked to friend Charles Fletcher Lummis that, “The arroyo would make one of the greatest parks in the world.”61

Perched at the edge of the arroyo, the Robinson house looks over the once natural landscape and the Colorado Street Bridge. View to the west, Laurabelle A. Robinson house.

Despite a modest budget, the Arturo Bandini house was a significant commission for Greene & Greene. It was in this house that the California influence first asserted itself in a significant manner. Isometric sketch, Arturo Bandini house, Pasadena, 1903.

Charles Greene was, unfortunately, incorrect about the arroyo’s prospects for development, his prediction somewhat naïve in hindsight, as President Roosevelt’s advice was not heeded. While the city of Pasadena acquired significant parcels of the land, much fell into private hands. Houses began to appear, not just on the edges of the arroyo but in the arroyo proper. Certainly not as disastrous as full-scale commercial development, this encroachment did alter the character of wilderness the arroyo had possessed. Some clients preference for building at the arroyo’s edge is easily understood, however, not only for the sweeping views afforded by such a location but for the recreation it provided prior to development.

Charles Greene wrote that “Habits and tastes i.e., life of the owner” should, in part, determine the style of a house. For the Bandini house, Greene & Greene fulfilled this requirement, and in the process found the genesis of the style that would define their careers. Interiors, Arturo Bandini house.

The Craftsman article notes that, “The tendency toward out-of-door life, the love of light and air and growing things is developing in the West.”62 It seems likely that such a tendency already existed in that part of the country and that many Easterners were only recently made aware of the West’s unique natural gifts. In any case, Charles and Henry supported this trend, whether recent or long existing, via their designs — designs with integrated gardens, patios and porches, numerous routes of egress and a feeling of belonging to the landscape.

Transplanted Easterners exerted significant influence on Greene & Greene at the earliest stage of their practice. The exponential growth in Southern California during the last decades of the 19th and first decade of the 20th centuries was due to migration — migration from the East and Midwest of those seeking opportunity, fortune, climate and good health. However, like the traveler seeking a hot dog in Paris, these newly minted Angelenos didn’t always adapt to their new environment. A 1903 article by Grace Ellery Channing in Charles Lummis’ Out West addressed this point. “We cannot blame our Eastern ancestors for modeling their homes and gardens, as they framed their lives and laws, after English, Dutch and German models; but when the Easterner moves West and plants his snow-shedding roofs beneath a shower of rose-petals, and builds him his Dutch or English lidless house upon a shadeless sidewalk and then immures himself — it is time to call him back to the decencies.”63

Thus, Ms. Channing suggests, it was not uncommon for Southern California’s new settlers to bring with them the styles they knew and with which they were comfortable. The Spanish missionaries had, of course, done much the same thing with the California missions which were constructed to recall, to the extent possible given the rudimentary tools available, buildings from their native Spain. The mission fathers were well justified given the similar climates in Spain and Southern California. As Ms. Channing states, however, the Eastern and Midwestern arrivals, a group that included most architects practicing in the area, introduced a number of styles quite poorly suited to their adopted home.

An architect can do only so much to change a client’s mind. Greene & Greene had for a time been fighting a quixotic battle, attempting to convince Pasadena’s transplants to leave the traditional styles back East where they belonged.64 They had had some success in incorporating climate-appropriate features, such as broader eaves to protect living spaces from the harsh sun but had not yet designed a truly Californian house. In 1903 they were engaged by Arturo and Helen Elliott Bandini, clients for whom no convincing was necessary. Arturo Bandini was the son of Juan Bandini, one of the old Spanish dons with substantial land holdings in the old Rancho system. He had grown up in a true California house — a casa de rancho, a style described quite well by Helen Elliott Bandini in her opus History of California. “The homes were generally built around a court into which all the rooms opened, and were constructed of adobe bricks such as were used at the missions. In the better class of homes several feet of the space in the courtyard next to the wall were covered with tile roofing, forming a shaded veranda, where the family were accustomed to spend the leisure hours.”65

“Country house” and “elegant” are not contradictory. The Blacker house is well-described by both terms. It is a study in detailing and understated sophistication. Dining-room, Robert R. Blacker house.

The Bandinis requested a house that would recall the rancho homes of California’s recent past. The Bandini house would not be large nor grandly appointed. It certainly would not be one of the more lucrative commissions for Greene & Greene.66 Nonetheless, the Bandini house represented a significant opportunity for the brothers — it presented them with the occasion, for the first time, to design a house fully suited to its location. The result was a rustic, board and batten masterpiece with interior and exterior perfectly suited to the lifestyle of the clients.

With the Bandini house the Greenes had finally found a direction. Their well-known contributions to the development of the California Bungalow would soon follow. They were now on the evolutionary path toward their trademark style. Greene & Greene were certainly not alone in their recognition of the need for California houses. Fellow Pasadenan Elmer Grey spoke to this in a 1907 article in The Craftsman. Grey is quoted as saying of California architects: “If he has a proper sense of the fitness of things he will not implant amid the semi-tropical foliage of California such architecture, for instance, as the Queen Anne or the Elizabethan.”67

Around the San Francisco Bay, a number of architects created the California Bungalow suitable for the distinct climate of that area. This included eaves cut out above windows to allow in sunlight to dissipate the morning chill, quite unlike the requirement further south. Some of the best known architects in that area were in Berkeley, Bernard Maybeck and John Galen Howard, for example, where Charles Keeler articulated his version of the Arts & Crafts philosophy, California-style. “It has often been pointed out that all sound art is an expression springing from the nature which environs it. Its principles may have been imported from afar, but the application of those principles must be native. A home, for example, must be adapted to the climate, the landscape and the life in which it is to serve its part. In New England we must have New England homes; in Alabama, Alabama homes, and in California, California homes.”68

The clients of Greene & Greene, particularly the wealthy, were helping to create the California country house.69 They did not, of course, set out to do this, nor were they likely aware of it, but that is precisely what they did. Then as now, Pasadena’s Orange Grove Avenue was known as “Millionaire’s Row” for the string of elegant mansions along its length. Certainly the Gambles, Blackers and Fords, barons of industry, could have built there had they so desired. They, however, were not chasing acclaim or society. They sought the lifestyle afforded by locale. Marble mansions did not indulge that desire and were, at any rate, incongruous for that place and time.

One should not think of “country house” in the sense of country-style décor with stenciled furniture and punched-tin pie safes. The term, imported from England, denotes a house located outside the city. It is important to note that a country house is not necessarily a small or modest house. In the English idiom, in fact, these are typically impressive estates of the gentry. The United States also has its share of similarly impressive country houses. In The American Country House, the first example given by author Clive Aslet is Biltmore, the immense house built by George Washington Vanderbilt outside Asheville, North Carolina.70 Clearly then, modest size is not a requirement.71

Nor is modesty of appointment a prerequisite. A 1914 House Beautiful article about bungalows in Southern California addresses this point. “Among all that Southern California has to boast, there is nothing of which she is more justly proud than the charm of her country homes; … Many of them are unrivaled in their completeness, thoroughly meeting not only the individual needs of the owner and of the climate, but the demands of really good building as well. The construction, the decorative lines, the arrangement of the rooms, even the least detail of interior finish, coloring and furnishing are planned in consistent relation to each other, so that every little part will aid, both in making the practical working of the house as convenient as possible and in the creation of an original artistic effect for the whole.”72

With this definition in mind, it is quite clear that most Greene & Greene houses are in fact country houses. The Gamble house is included in a 1913 book entitled American Country Houses of Today.73 The impressive Fleischhacker estate in Woodside is similarly represented in an article for The Architectural Record, by John Galen Howard, about country houses on the Pacific coast.74 The Blacker, Ford, Robinson and Pratt houses all fall into the category as well. One could argue that the Thorsen house is not a country house given its setting in Berkeley and its siting on a standard urban lot, but this only makes it the exception that proves the rule since it shares a great deal with its predecessors to the south.

The final word on the topic goes, quite appropriately, to John Ruskin, who spoke very eloquently on the subject of the English country house. His words are quite befitting the work of Charles and Henry Greene, two young men creating perfect houses an ocean and a continent away. “And in actual life let me assure you that the first ‘wisdom of calm’ is to plan and resolve to labour for the comfort and beauty of a home such as, if we could obtain it, we would quit no more. Not a compartment of a model lodging-house, not the number so-and-so of Paradise row, but a cottage all our own, with its little garden, its pleasant view, its surrounding fields, its neighbouring stream, its healthy air and clean kitchen, parlours and bedrooms. Less than this no man should be content with for his nest; more than this few should seek; …”75

The landscape of the Van Rossem/Neil house. A perfect illustration of Ruskin’s “…cottage all our own, with its little garden…” View of north façade, Josephine Van Rossem house #1.