MISSIONARIES AND MUSLIMS

The Red River remained a topic of conversation as the entire party rested for a week in Chien-shui, another prolonged halt underlining the physical weakness of the explorers and their escort. For Garnier the river and its possibilities for navigation were to become later obsessions just as demanding as the Mekong once had been. Still without a certain end to the expedition, and with a continuing desire to plot the course of the Mekong's upper reaches, Garnier speculated on the Red River as a future route into China. Proudly patriotic, even chauvinistic, there was no doubt in his mind that France alone should benefit, if his information were correct and commerce could pass up and down the river of Tonkin. He recalled his thoughts in 1870 and put the matter clearly and bluntly. This was “a commercial concern with a great future and an exclusively French affair.” Lagrée shared his view and recorded it in the last report he made before he died. For all the Frenchmen in the party the assumed value of the Red River replaced the hopes they could no longer hold of navigation along the Mekong.

By December 9 the expedition was ready to move forward again with K'un-ming, the capital of Yunnan province, the next major goal. Their path took them through an area of ruined tombs, with marble pillars and porticos, which evoked an incongruous sense of the countryside about Rome. Thoughts quickly returned to the reality of China, however, when two galloping horsemen overtook the party bearing news from the Governor of Chien-shui. Not long after Garnier's frightening experience in the city, one of the culprits in the affair had been seized by the local officials. Throughout the explorers' stay in Chien-shui, the stone thrower had been held in a pillory by one of the main gateways into the city. Now, the horsemen told the explorers, he had been executed, his head struck from his body. While still in Chien-shui the Frenchmen had heard rumors that this was to be his fate, but they had not believed it would actually happen. They claimed later they would have tried to prevent the execution if they could.

At midday, with Chien-shui well behind them, the party found welcome relief from the usual weary routine of walking. The first important settlement along their route to K'un-ming was the town of Shih-p'ing and this they could reach by boat, sailing across the lake that lay in their path. Arriving there the same evening, the party rested for a day before heading north once more on December 11. Their route took them over a succession of hills and valleys where stands of cypress trees gave an almost alpine appearance to their surroundings. With the altitude increasing, the party was moving out of the upper basin of the Red River. For a short while, it seems, Lagrée hesitated over the northern route they were following. To have turned east again would have taken the party by land to a point on the Red River where boats could carry them easily to the sea. There was further discussion, even argument. Whatever his interest in the Red River, Garnier still hoped to travel westwards towards the Mekong, and to do this would require passports and advice that could only be found in K'un-ming. Lagrée acquiesced. None of the others was yet as ill as the leader, and he recognized the importance the younger men placed on attempting to discover more about the Mekong. He was still the commander of the party, but this was no time to enforce an unpopular decision at all costs.

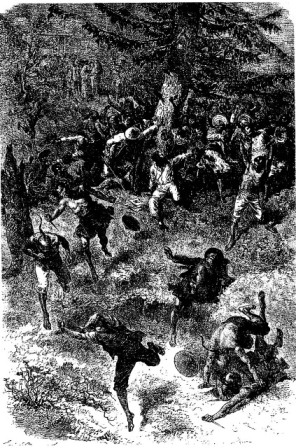

So they continued north, to T'ung-hai, where, in the evening of December 14, the whole party found itself the object of unrestrained and potentially dangerous curiosity. The circumstances were similar to those Garnier had experienced. The explorers' arrival in T'ung-hai was the signal for hundreds of townspeople to gather about the pagoda in which the party lodged. Movement in and out of their quarters became impossible, and the posting of a Chinese guard about the walls only increased the interest of the crowd. With the bolder members of the crowd scaling the surrounding walls and roofs to gain entry into the pagoda, the Chinese soldiers standing guard prepared to fire their antique matchlocks. If this sight was insufficient to repel the curious, the view of the expedition's escort drawn up behind had its effect. Fixed to the escort's rifles were long sword-like bayonets, a combination of weapons unknown to the Chinese of T'ung-hai. The party passed an untroubled night. The next day it was Delaporte's turn. Seeking a high spot from which to sketch the town, he suddenly found himself at the center of a brawl as the curious inhabitants fought each other to gain a view of the artist. He extricated himself by waving his revolver threateningly and through the timely arrival of Joubert and de Carné. Months before, as the expedition had moved slowly and monotonously along the Mekong below Vientiane, Garnier had noted that a day without incident was a “disappointment.” Incidents were certainly not absent from this stage of the journey, but now more than ever before the emotional cost was high.

It was snowing when the expedition left T'ung-hai on December 16, the first snow Garnier had seen for six years and the first that the Vietnamese in the escort had seen in their lives. Their first reaction was of wonder and delight. This quickly changed to painful distress as their bare feet encountered the snow covering the path. Never previously having worn shoes, the escort's feet had hardened over the years; so they had been unworried by the earlier stages, when the Europeans in the party had found marching barefoot to be such a painful business. But neither the feet nor the hands of the escort were hardened to resist cold, and tears ran down their cheeks at the pain. All in the party suffered. “This day's march both for them and for us was one of the most painful of the journey,” Garnier wrote. “Our long beards bristled with icicles, and compass, pencil, and paper slipped from my numbed fingers.” The next day was little better. The sun shone but the temperature remained below freezing throughout the day as they hurried on to Chiang-ch'uan. Reaching this town the same day, the explorers took advantage of warmth and hospitality, untroubled by bands of curiosity seekers, to plan ahead.

Delaporte disturbed while sketching.

They still knew little more than the bare essentials of the political and military situation in Yunnan, for, even had they not lacked a proper interpreter, the circumstances changed almost from day to day. K'un-ming remained in the hands of the imperial government, largely because one of the principal Muslim rebels, Ma Ju-lung, a man of great military capacity, had defected to the imperial side in 1860 and, appointed as a general, provided effective leadership against his former comrades in arms. The paradox of such a situation was given further piquancy by the fact that Ma Ju-lung had been joined in his defection by the man who, between 1855 and 1860, had been revered as the spiritual leader of the Islamic rebels. This was Ma Te-hsing, known to his co-religionists and to the French as Lao Papa. As the one man of his people who had made the pilgrimage to Mecca, Lao Papa's religious standing was unchallenged. Why he and Ma Ju-lung changed sides is still unknown.

In late 1867 as the explorers approached K'un-ming the Islamic revolt had many of the elements of a stalemate. To the west, based about Ta-li, the rebels were in largely undisputed control. In the eastern and northern sections of Yunnan, the imperial government's writ ran uncertainly, sustained to a considerable degree by the “reformed” rebel Ma Ju-lung. Yet if stalemate described the situation, from a broad point of view, the threat of sudden changes of control over large regions of the province remained to trouble the French party, and to make discussion of travel to the region near Ta-li pointless until further information was to hand. The wisest decision, it seemed to the men warming themselves in the house of the chief mandarin of Chiang-ch'uan, was to write ahead to K'un-ming to give notice of their intended early arrival. As this information was carried ahead by messengers, the expedition would follow as quickly as possible, spurred on by the disquieting news that the Muslim rebels had achieved new successes within thirty miles of K'un-ming.

Partly restored by the two days of rest, the party set off again on December 20. Even after all their experiences they were quite unprepared for the sight that met their eyes shortly after they had left the town. On a bare untilled plain running gently down to a lake lay hundreds of unburied coffins. The explorers were in one of the regions where the scourge of cholera had followed close upon the heels of war. Local custom called for the bodies of those who died in an epidemic to be left above ground in their coffins for a period, and this requirement had created the macabre landscape through which the party passed. Delaporte's sketch of the scene is evocative. The expedition's route wends through the countless scattered coffins as the men march forward under a gloomy sky. Garnier's brisk commentary barely hides a wealth of graveyard horror. “Chinese coffins,” he observed matter of factly, “are, happily, more tightly closed than our own so that only occasionally did foul odors escape from this pile of cadavers.” Nonetheless, it was a “genuine relief” to quit the coffin-covered plain and climb into the nearby hills.

The coffin-covered plain outside Chiang-ch'uan.

The next three days were filled with arduous marching. At one point their route took them to a height of seven thousand feet, and along their way they encountered frequent reminders of the war that ravaged the province in the succession of burned-out villages and abandoned fields. By the fourth day after leaving Chiang-ch'uan the countryside's somber aspect had changed. In place of devastation they saw carefully tended fields and irrigation canals. The route they followed became a road rather than a stony path, and they shared its surface with a bewildering confusion of travelers: caravans of beasts bearing merchandise, human porters, and the curtained litters of those who could afford to be carried rather than walk. As they had done before, the Frenchmen reflected sadly on their worn and dirty clothing, which contrasted so sharply with the silken robes of the Chinese officials and merchants who paused to stare at them.

The first view of K'un-ming came at midday on December 23. Under the clear blue sky they saw the great city in the distance, its crenelated walls rising in stark relief. As they halted to look at this ancient city, set six thousand feet above sea level, a horseman rode rapidly out towards them. The rider bore a letter for Lagrée, sent by a missionary and in French! This was more than they had hoped for. They knew there were missionaries in northern Yunnan, but they had no certain information about their nationality. There could be no better greeting to such passionate patriots than the promise of the letter that its writer would see them “à bientôt.” With light hearts they passed through the great southern gateway into the city, cheered by the thought of an early meeting with one of their countrymen and joyfully observing the signs they saw all about them of K'un-ming's commercial importance.

This was the biggest city they had seen since they left Saigon. That had been eighteen months ago. Luang Prabang had blended Arcadian surroundings with picturesque buildings, Yüan-chiang had held a special charm in its setting beside the Red River, but K'un-ming was something else again. Despite the damage inflicted during the assaults mounted by the rebels at the beginning of the decade, the city's fortified walls were in good repair. The streets within were lively with constant streams of passersby. And there seemed every evidence that here in K'un-ming the fabled riches of southwestern China were present in abundance. Shop front succeeded shop front; the merchants' goods were displayed in carefully arranged cases. The uniform color of the buildings was relieved in the commercial quarters of the city by the thousands, as it seemed to Garnier, of golden painted characters hung above the shop fronts proclaiming the nature of the merchandise for sale. Guided through the busy crowd that parted to let them pass, the explorers were brought to their lodgings, a section of the examinations palace. Here, in less troubled days, the young men who sought admission to the imperial bureaucracy submitted to the traditional examinations in the Confucian classics. Set on a hill with a fine view out over the countryside and comfortably furnished, the building offered a happy contrast to the poverty of so many of their recent lodgings.

Father Protteau, for such was the writer of the letter of welcome they had received earlier in the day, soon appeared at the explorers' quarters. This was an emotional moment, their first meeting with a compatriot since the anticlimactic encounter with Duyshart south of Luang Prabang eight months earlier; and he, after all, was not French by birth. But it was a meeting that held a different significance for each of the various members of the expedition. For Lagrée, the missionaries the expedition met at K'un-ming were to be admired for their devotion and respected for their faith. His Jesuit schooling required no less than this, and probably ensured more. The youngest member of the party, Louis de Carné, was a fervent believer, a passionate Catholic who saw in his religion a bastion against the insidious dangers of socialism. To find men of God in the isolated southwestern corner of China was a further testimony to the spiritual power of the creed he held dear.

To Garnier the presence of the priests was another matter altogether. He was, conventionally, a member of the Catholic faith, but in his private letters he revealed that his degree of religious conviction was, at very least, debatable. He could conceive of the existence of a divine spirit, he once observed, but he had no belief in the claims of religion revealed through a savior. If Garnier had a sustaining personal faith it was the worship of his country's glory. He summed up his views of men such as Father Protteau in an uncompromisingly frank observation: “One must make use of missionaries, but not serve them.” Like many of his naval compatriots in the East, he had seen the contrast between the missionaries' claims of success in making converts and the reality of meager achievement. If they could serve France, then so much the better. But often, as he made bluntly clear, this was not a role missionaries played.

The man who now stood before them did little to change either de Carné's or Garnier's mind. The young diplomat saw in Father Protteau a living martyr. Here was a man who had sacrificed all his private interests and risked death to convert the heathen in one of the most remote corners of the globe. When, two days later, de Carné attended a midnight Christmas mass and received the Host and took wine from the priest's gnarled hands, he found it a moving religious experience. Garnier was present at the mass, too, as convention required; his real interest in Father Protteau, however, related to the amount of information the missionary could provide. There was much but not enough.

Father Protteau could, at least, solve the mystery surrounding their experience at Keng Hung. The cause of their difficulties in late September, it transpired, had been the inability of the Keng Hung officials to make an accurate translation of a letter sent by the Viceroy of Yunnan. This great official had written on the explorers' behalf, authorizing their entry into China but warning against the dangers they might find on certain routes. The warning in his letter had been mistaken for an interdiction. As for the letter from “Kosuto,” this had been sent by Father Fenouil, Protteau's immediate superior and the Deputy Apostolic Vicar in Yunnan. Fenouil had written to confirm all that had been said in the Viceroy's letter. The French party was welcome in the areas controlled by the imperial government. This was partly so, Protteau explained, because of the way Father Fenouil had embraced the imperial cause. He was indeed, as rumor had so often told them, a renowned maker of gunpowder. Unfortunately for the utility of his efforts, his powder magazine had blown up recently, the result, it was thought, of sabotage by the Islamic rebels. The news confirmed Garnier's belief that the missionaries of Yunnan were unwisely set upon a path of excessive identification with the interests of the local government.

Father Fenouil was expected in K'un-ming shortly, but before this meeting the explorers were concerned to present themselves before the local authorities. A visit to the Governor of the province passed quickly and courteously. Then it was time for the French to present themselves before General Ma Ju-lung. Although the Muslims of Yunnan had been prevented for centuries from pursuing their ancient employment as soldiers, Ma Ju-lung had readily captured the spirit of his martial ancestors. He was a large, and to the French a gross figure. As proof of his military prowess he insisted on showing them the wounds that covered his body, pulling open his tunic so they could better see the scars. Although the Frenchmen suspected from Ma Ju-lung's red-rimmed eyes that he had spent the night carousing, their host would not join them in the banquet that he later laid before them.

As the explorers feasted on swallows' nest soup, fishes' entrails, and lacquered duck, the general and his subordinates sat and watched. It was the Muslim month of Ramadan, and as a believer Ma Ju-lung could not eat until the sun had set. But perhaps most striking of all to the explorers was the manner in which the Muslim general surrounded himself with weapons. Unlike the antique guns that had been the equipment of all the Chinese soldiery they had seen so far, much of Ma Ju-lung's armory was stocked with modern equipment. There were ancient blunderbusses, it was true. Besides these, however, were repeating rifles, carbines, and revolvers. Not only that; the evidence was all about them of Ma Ju-lung having tested his weapons. Not a piece of furniture in the general's quarters had escaped use as a target.

Picturesque as he was, Ma Ju-lung was a worrying factor in the explorers' calculations. Could they depend on him? He remained a follower of Islam, so that his enemies were his coreligionists. It was true that when he changed sides he had acted quickly to remove any doubts from the minds of his soldiers as to where their new loyalties should lie. Assembling his troops, he executed twenty among them who had dared to criticize their leader's actions. But that had been years before, and doubts about his intentions remained. Father Protteau, whose spiritual faith waged a constant battle with very earthly fear, wished himself back in the mountain refuge where he had fled on previous occasions when the Muslims threatened K'un-ming. For the French party the best assurance of Ma Ju-lung's goodwill seemed to lie in the fact that Father Fenouil had written on his behalf to the French diplomatic mission in Peking. Whether through his own wish, or because of Ma's threats, as he later himself maintained, Fenouil had written to the French Legation to argue Ma Ju-lung's case to the imperial authorities for increased supplies of men and weapons to prosecute the war against the rebels.

Finally, on January 2, 1868, the expedition's members met Fenouil. Garnier wrote that the French members of the party “loved” this missionary, but Garnier himself soon gives the lie to this description. He may have “loved” Father Fenouil's patriotism, for this feeling was present in abundance. For the rest Garnier's portrait of the Deputy Apostolic Vicar is a cruelly accurate delineation of a man and priest thrust into a role for which he had little talent and less experience. He was a different man altogether from his subordinate. Father Protteau, in the Frenchmen's eyes, had become almost Chinese, a peasant Chinese. His otherworldliness could be amusing and even irritating. Delaporte found this one day as he returned from an expedition on horseback. Crossing a wide and fast-flowing stream by means of a tree trunk serving as an improvised and shaky bridge, he spied Protteau on the other bank. The crossing achieved, Delaporte, still shaking from the experience, was told by the old missionary that there had been no need to be afraid. The priest had accorded him absolution in case he fell into the water and drowned.

Father Fenouil, too, had adapted to his surroundings, but in a very different manner. The treaties exacted from the Chinese government following the Anglo-French occupation of Peking in 1860 had allowed foreign missionaries to assume the titles and privilege of mandarins. Fenouil, a vigorous man in his forties, had hastened to avail himself of these provisions. He dressed in the robes of a mandarin of the appropriate rank, rode in a sedan chair proper to his dignity, and required the proper salutations in return. His decision to become closely involved in the affairs of the province had a cost, however, for Fenouil's name was now well known to the Muslim rebels and he feared for his life should he ever encounter them. Yet, in Garnier's skeptical eyes, this fear had not deprived Fenouil of a secret wish to act as arbiter between the two contending sides in Yunnan. For the moment he was able to render one vital service to the expedition. Acting on the French party's behalf, he negotiated a loan equivalent to five thousand francs from Ma Ju-lung. The expedition's reserves of money had finally been exhausted, and to proceed further without funds was impossible.

How to proceed, and where, remained undecided matters. Lagrée put the question of their future route to his companions, and the opinion was unanimous that they should make a final effort to travel west towards the Mekong and Ta-li. Lagrée's principal biographer doubts that this was Lagrée's personal choice, arguing that the leader now placed the need to preserve a sense of unanimity above his own judgment of what was most desirable. This may well be so, but unwillingly or not Lagrée now worked to gain the information and the papers that might make a visit to Ta-li, and even the Mekong, possible. Ma Ju-lung rejected Lagrée's first proposal: that the expedition should be escorted to the nearest rebel post and left there to fend for themselves. The next plan, however, was accepted as more reasonable. The expedition would first travel north and then turn to the west, hoping in this way to delay their meeting with the rebels until they were close to the seat of Muslim power, the city of Tali. To aid in this endeavor, the Frenchmen now looked to the former spiritual leader of the rebels, Lao Papa, the one man among the Yunnanese followers of Islam who had made the haj to Mecca.

The French approach to Lao Papa was calculated to play upon his widely known vanity. Many years before, he had studied astronomy in Istanbul. He had even spent a year in Singapore to verify the information that days and nights on the equator were of equal length. Now, alerted to the presence of the Frenchmen, Lao Papa sent them a series of questions indicating his interest and uncertainty over a number of astronomical matters. The rest was easy. The Frenchmen sent messages indicating their admiration for Lao Papa's learning. Then, in actual audience with the old haji, Garnier rendered him the best service of all. When he had sojourned in Singapore, Lao Papa had bought a powerful telescope, but on his return the instrument had proved useless. Could the Frenchmen help? Indeed they could, and with the aid of a vise Garnier adjusted the misplaced lenses. For Lao Papa the wishes of the expedition became his own. At their request he furnished a lengthy letter calling on his co-religionists to aid the Frenchmen in their travels towards Ta-li. Despite his association with the imperial forces, the eighty-year-old Lao Papa was still highly regarded by many on the other side, and the French party now seemed well prepared for a passage to the west.

Leaving K'un-ming on January 8, the Frenchmen knew that they were within two weeks' march of the great Yangtze River, which could carry them swiftly towards Shanghai on the China coast. This was a seductive vision but it was counterbalanced by a conviction of the scientific value of exploring the unknown country to the west. Accompanied at this stage of their travels by Father Fenouil, the explorers reached the town of Yang-lin in the afternoon of January 9. Once again there was a potentially dangerous incident. No sooner had the French party occupied quarters for the night in an inn than a party of Chinese soldiers sought to dislodge them from their rooms. The invaders were repulsed by the expedition's escort and, while the Vietnamese militiamen stood guard with fixed bayonets, Garnier called on Father Fenouil to alert the frustrated soldiery to the expedition's status and the nature of the passports its members bore.

When this seemed to have no effect, Garnier told Fenouil to announce that the French party was ready to fire if there were any further attempts to enter the expedition's quarters. “But,” Garnier notes, “the poor priest had completely lost his head before the unheard of audacity of our Vietnamese escort … instead of threats he addressed entreaties to the soldiers; he admitted our faults; he suggested that we were ignorant of local customs; he said we begged for pardon.” In short, the missionary acted as Garnier would have expected. When, following Fenouil's statements, a Chinese officer rushed in to make himself master of the apparently craven foreigners, he ran against one of the escort's bayonets. An end to the fracas came soon afterward. Lagrée, already suffering acutely from the dysentery that was to bring his death in a matter of weeks, left Garnier and the agitated Fenouil to bring the encounter to a satisfactory conclusion.

The next day Fenouil left the party to travel north and a little east to Ch'ü-ching, his base in the relatively secure eastern regions of the province. Even Garnier seems to have been touched by the prospect that this missionary might never see another of his countrymen again. The party's immediate concern, however, was to travel forward as quickly as possible despite the declining health of the leader and of an increasing number of the escort. On January 14 Lagrée was too ill with a fever to permit the party's further progress. As they continued on the next day, their passage was painfully slow. Although they had horses with them, Lagrée was too ill to remain seated in the saddle, and he took his turn, along with the sick members of the escort, in an improvised litter. The party was traveling over a plateau eight thousand feet high, and to match the cold there was a bare landscape, whipped by a wind that whistled mournfully through the steep valleys running away on either side of their route. Not until January 18 was there any relief. On that day the party completed its travel to Hui-tse by boat, putting behind them for the moment the need to walk. As the early winter evening closed about them, the expedition came to Hui-tse.

With the party halted once more, Lagrée made a supreme effort to carry out his role as leader. For a few days he was able to meet with the local officials and even to consider the possibility that he too would travel to Ta-li. But his indomitable spirit could not overcome the fatigue resulting from the combined effect of three illnesses. By now it was unmistakable that he was suffering from a severe form of dysentery. Like many, perhaps all the others in the party, he had come to look on malaria as an almost routine affair. And finally his throat infection, which in the warmer air of Cambodia had improved if not disappeared, once more troubled him.

The last meeting of the whole expedition was held about Lagrée's sickbed. Again he sought opinions rather than giving an order. The group was in favor of an effort to reach Ta-li, and Lagrée gave his approval. Shortly after, a letter arrived from Father Fenouil telling the explorers that the local mandarins at Hui-tse were disturbed at the expedition's plans and begging them not to attempt a journey to Ta-li. This could only spur Garnier on. There was no way of knowing, he argued, what had inspired the missionary to write in these terms. His opinion was not to be trusted since he was clearly swayed by whatever was the most powerful influence at any given time. The second-in-command now drafted instructions for the party about to attempt the journey to the west. This was the last official document signed by Lagrée. How much he grasped of its import is debatable. In any event, the final paragraph of the instructions seemed as much due to Garnier's inspiration as to thought by the now almost totally incapacitated leader. “If, at any time in the journey,” the final paragraph read, “Monsieur Garnier thinks that he might easily reach a point anywhere on the Mekong, he should do so alone and as quickly as possible.” As a last instruction from Lagrée, Garnier could not ask for more.

On January 30 the party heading for Ta-li left Lagrée at Hui-tse. Shaking the leader's hand for the last time were Garnier, Thorel, Delaporte, and de Carné. They were to be accompanied by five men from the escort. This time Garnier was not traveling with Tei, whose own illness forced him to remain at the base camp. Left behind with Lagrée were Joubert, the French sailor Mouëllo, and three members of the Vietnamese escort.