“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

—LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN

In a video that became a brief Internet sensation in 2008, a black journalist walks toward the camera slowly, microphone in hand, intoning in standard, serious reporterese:

What really happened on that Thursday here at Augusta High School that led to Chris Woods’s death?

Suddenly, he doubles over in disgust and whirls almost 180 degrees around, spitting. A bug has flown into his mouth. The next few words to come out are not so standard. His accent changes completely as he says

The fuck is that? Shit! … I’m dyin’ in this fuckin’ country-ass fucked-up town. Shit flyin’ in my mouth. Da fuck! I can’ see, pollen … les’ get da fuck out this country motherfucker.

I’ve probably watched the video fifty times, and it makes me laugh every time. I’ve quoted the video so often that a friend suggested I call this book Shit Flyin’ in My Mouth.

But I don’t like the title the video is given on YouTube: “Ghetto Reporter.” The comments below the video are revealing:

i love how is voice is so pro in the beggining then the real side of him shows!

I love how he talks white, but after the bug flies in his mouth, he talks ghetto!

it is funny how he goes like HICCUM [the spitting sound] when he gets bug in his mouth fucking nigger! haha lolz

You don’t have to be a racist to find the juxtaposition of Broadcast Standard and (highly) extemporaneous Black English funny. Comedy depends on putting incongruous things side by side. But the comments reveal that many viewers saw more than funny incongruity. For them, the black reporter had managed to put on a veneer of respectability, but it was so shallow that it fell away instantly upon surprise, revealing the thuggish “ghetto” beneath.

I saw something different. My wife, who is from Denmark, speaks an incredibly fluent English that never fails to surprise me. Ninety-eight percent of her speech in a given week is in English. But as soon as she stubs her toe on our bed frame, she always says the same thing: For Satan!, cursing in Danish. Don’t be confused by the surface similarity with English; for means in Danish what it means in English, and Satan is spelled the same way, but this isn’t a cute equivalent of “The devil!” For Satan is one of the rougher curses in Danish, about as taboo as what many English speakers would say upon a good hard toe-smashing: Shit! or Fuck!

What happens to my wife is the same thing that happened to the “ghetto reporter”: upon a sharp and nasty surprise, they switch immediately into their home language—or in the reporter’s case, dialect. The reporter, Isiah Carey, isn’t “ghetto” with a veneer of respectability. He is a speaker of Black English from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, who has learned formal standard English in the course of a career that would win him several journalism awards. The fly incident shows him not to be barely civilized but bidialectal. A few other videos of Carey horsing around between takes have made it to YouTube under the series title “Roving Reporter Etiquette Lessons.” They show him comfortably switching back and forth between Black and standard English. One video shows him professionally finishing a take, pausing for a few seconds, and then growling at a dog that’s been yapping nearby, “I’m gon’ kick yo’ ass.” No linguist would lift an eyebrow at this; remember “code switching” from the last chapter. Surprise or emotion almost invariably make people switch to their first language or dialect, as predictable as swearing.

The idea that the reporter is doing the same thing in something called “Black English” that my wife is doing in Danish would rub a lot of sticklers the wrong way, though. Danish is the language of Kierkegaard and Niels Bohr; the way the reporter swears makes sticklers think of black thugs and the crisis of education among America’s black youth. In other words, the notion that Black English is a standard dialect, a native language with grammatical and phonological rules, on par with Danish, seems borderline insane.

But linguists have long known that Black English isn’t a broken-down version of “real” English. It isn’t being made up by speakers who don’t care about grammar. It has a grammar, in the Chomskyan sense of a set of rules that produce acceptable sentences. Violate them, and you’ll sound odd. For example, the verb “to be” must be left out of many sentences in the present tense: She my sister. But when it is used, it preserves a distinction (linguists call it “aspect”) that doesn’t even exist in standard English: He sick means he’s sick right now, while He be sick means he’s sick usually or frequently. Other grammar features are double negatives (Ain’t nobody gonna do that) and greater use of “do” as an auxiliary (I done told you a thousand times). Phonetic features include the “-in” ending on verbs (shit flyin in my mouth).

Some of these are regular features of other languages, too. We have seen double negatives in other European languages. Pronouncing the “-ing” ending as “-in” used to be the high-class pronunciation in Britain. And “do” has an idiosyncratic function in standard English, too: why do we use it to form questions, turning “You have a car?” into “Do you have a car?” Black English (which shares this feature, and others, with southern white English) just extends this “do support” a bit further.

Another distracting factor is that many black Americans don’t speak black dialect, either because they never learned it or never use it: think Condoleezza Rice. But many speak both Black English and standard English, and comfortably switch between one at home and among black friends, and the other at work with white colleagues. And code switching isn’t (pardon the pun) just black and white; there are intermediate varieties that use some but not all features of Black English. One speaker can move between them in a single conversation. This tempts the conclusion that sometimes black people speak “carefully” and sometimes “lazily.”

Americans’ familiarity with dialect continua is also poor. The average speaker of a European language is familiar with different “versions” of his language: Sicilian Italian, Plattdeutsch (“low German”), two standard versions of Norwegian (Nynorsk and Bokmål), and so on. Many of the Europeans who speak these dialects are proud of them. They recognize High German or Florentine Italian as de facto standards. Some have feelings of inferiority about their speech, derided as “slang,” “jargon,” “argot,” or “patois” by speakers of the prestige dialect. But plenty of others would never dream of seeing their nonstandard varieties as degraded or lazy. No proud Sicilian American would accept that his grandmother speaks “ghetto Italian”; different, yes, ghetto, no. Plenty of Jewish Americans are proud of Yiddish and would never let it be called “ghetto German” either. Nor would most Americans dream of calling this “ghetto English”:

But, Mousie, thou art no thy lane,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men

Gang aft a-gley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

The author is, of course, Robert Burns, the poet beloved for his use of Scots English. Many Americans of Scottish heritage drink a dram in his honor on January 25, Burns’s birthday. His poetry in dialect helped bring honor to a people looked down on for centuries by the dominant English. Scots are just one example of a group proudly embracing their nonstandard dialect.

Yet the controversy over “Ebonics” showed just how willing many Americans are to frown on one English dialect in particular, Black English. In 1997 Oakland’s school board decided to recognize, and use as a teaching aid, the “primary language” of most black students, which they called Ebonics. It was a word that almost no one had ever heard before. (It had been coined, with hardly anyone noticing, in the 1970s.) But within weeks of the 1997 Oakland school decision, the whole country was talking—and laughing—about it.

Oakland’s heart was in the right place. The school board drew upon a hazy understanding of dialectal linguistics to argue that black kids come from a different linguistic background and that recognizing this would help them learn standard English faster.

But the board made major mistakes of both substance and marketing. Probably the worst was “Ebonics” itself, a goofy name that lent itself to immediate parody. The school board also shouldn’t have referred to it as a “language”; though “dialect” and “language” have no clear-cut definitions, virtually all linguists would call Ebonics a dialect or variety of English. The word “language” exaggerated how different “Ebonics” really is. A third stumble, both political and linguistic, was the board’s clumsy reach for a proud Afrocentric heritage, claiming that Ebonics drew on a past in the linguistic forms of West African languages—a highly debatable, probably untrue assertion that was anyway unnecessary to their case.

And perhaps that case did not even need to be made; some linguists argued that Oakland would have been better off focusing on improving its dismal inner-city schools generally, not on giving black kids an exoticized, partially invented “foreign”-language background as an explanation for bad performance. But those writers also based their claims on evidence, not a political rejection of Black English as a valid variety. John McWhorter, a black linguist then teaching at Berkeley, pointed to studies showing Ebonics-like teaching approaches as unsuccessful. Others disagreed: the Linguistic Society of America noted that in Sweden, teaching kids standard Swedish through approaches that recognized their nonstandard Swedish dialectal starting points had been shown to be effective. Similar approaches had shown the same elsewhere. The LSA thus said that the Oakland school board’s general thrust was “linguistically and pedagogically sound.” The point is that the linguists, even if inclined to the political left and friendly to the Ebonics approach, thought of this as a suitable question for data gathering and study, not a theological first-principles approach that Ebonics simply had to be wrong.

Not that the linguists were listened to: The New York Times, which published several editorials and op-eds criticizing Ebonics, rejected several op-eds from linguists making the case for Oakland’s approach. The debate in the real world showed not only a divorce from the linguist’s data-driven approach; most people didn’t know what Ebonics was about at all. What Oakland had proposed was teaching black kids to recode, or translate, their Black English into standard English. But this crucial point was utterly lost on the public. Instead, what filtered through to the average, busy news reader were the big, bold headlines reading:

Oakland Schools Sanction “Ebonics” (Chicago Tribune)

Black English Recognized for Schools (The Philadelphia Inquirer)

Oakland Schools to Teach Black English (Miami Herald)

The words “sanction,” “recognized,” and especially “teach” gave a false impression that thousands of jokesters were only too quick to seize: that black kids, having been recognized as too dumb to learn in real English, would be taught algebra and literature entirely in Ebonics. The college humor magazine that I worked on at Tulane was a typical example. We wrote that

Like George Shaw’s strong-headed Eliza, the black youth of America should be taught the value of communicating properly, for therein lies their best leg up from poverty. Perhaps a modern adaptation of the lessons of Pygmalion would help to do so: My Fair Sista Sista, a musical comedy in which young flower girl Moiesha Doolittle repents her attitude of “Just step off, Henry Higgins. Just step off,” and learns that young ladies shouldn’t say “The rain in Spain be fallin mainly in the hood, nigga.”

We, like so many others eager to get a good line in, didn’t realize that “teaching the black youth of America the value of communicating properly” is exactly what Oakland was trying to do (if you replace “properly” with something less value-laden, such as “in standard English.”)

Essentially, the problem Oakland was dealing with is the same one seen among Arabic speakers today. Children arrive at school being told that the language they have been speaking all their lives so far is debased and without value and they must immediately begin learning the “real” language. The effect on their motivation and connection to reading doesn’t need to be guessed at (though it can be, correctly): it produces apathetic readers who feel that writing culture is not for them.

James Baldwin, the black novelist (who wrote, yes, in standard English), put it this way in a 1979 article:

A child cannot be taught by anyone who despises him, and a child cannot afford to be fooled. A child cannot be taught by anyone whose demand, essentially, is that the child repudiate his experience, and all that gives him sustenance, and enter a limbo in which he will no longer be black, and in which he knows that he can never become white.

Baldwin’s prognosis may seem too gloomy today, but the kernel of truth remains. Blacks have always been America’s most beaten-down minority. At the same time, they have been told that the route to success in America was via education. The Ebonics movement wanted to give black kids a crucial tool, standard English, without telling them that their Black English was wrong, it was merely different and would have to give way to standard English in academic life. But the outrage over Ebonics proved that learning “white” English wasn’t enough; from the conservative schoolmaster’s point of view, Black English had to be shamed out of black children.

The Ebonics controversy taught linguists that they had badly, or at best incompletely, put their ideas across to the general public. Several of those ideas should have played a bigger role in the Ebonics story. One is that all language varieties are highly regular. Linguists have yet to discover a language with no rules, which speakers simply make up as they see fit. This can happen, briefly, when two peoples come into contact with each other and don’t share a language. But if that improvised language persists for long enough to be learned by children, it becomes standard and predictable. In the linguist’s terminology, the improvised “pidgin” becomes the regularized “creole.”

Another tenet taken as an article of faith by most linguists is the fundamental equality of languages. Virtually every language—and every dialect, including Ebonics—has the capacity to express virtually any thought. True, they may need specialized vocabulary for, say, talking about subatomic particles or hydrochlorofluorocarbons. But this is actually fairly easy. Most languages can accept new words without much trouble. The point is that all languages have the structural features they need to be great languages capable of expressing the most sophisticated thought.

This is, without doubt, going to be a long, hard sell for the linguists. People have very-high-stakes relationships with their languages. They frequently believe them to be uniquely expressive, logical, or beautiful. And they are frequently tempted by myths about the deficiencies of other languages they don’t know.

Why do linguists think that most any language can do anything, while the Lynne Trusses of the world see linguistic incompetence all around them? Mainly because linguists and sticklers focus on different things. Sticklers focus largely on writing and see how most people don’t master the formal grammar or use the higher-level vocabulary of their language well. (They also, as we saw in chapter 2, often just make up new rules with no basis and then insist that mastery of those rules is the most basic sign of intelligence.) Linguists focus on speech and see how even small children, the uneducated, and, yes, speakers of frowned-upon languages and dialects can create an astonishing—infinite, even—number of novel utterances in a variety of situations, making themselves perfectly understood. To the declinists and sticklers, most people are idiots. To a linguist, mastery of the unbelievably complicated rules of language is so commonplace that it’s no surprise most people forget just what a miracle it is, in any language.

The belief that all languages are basically equal hangs together with—though it isn’t identical to—the belief that language is an innate human phenomenon. The “innateness” thesis is by no means accepted by all linguists. But it is accepted by many, including some of the field’s most famous names. Noam Chomsky posited, near the beginning of his soon-to-skyrocket career, that there must be a specialized part of the brain, a “language organ,” that is primed, waiting only for input, to learn the rules of any given human language. This is possible only because all languages—not just “Berlitz” languages such as Chinese and Spanish but every other one from Aari to Zyphe—are more like one another than any of them is to any other kind of language. Chomsky called these features “Universal Grammar” and set out to find them.

The matter is still one of great debate. But when linguists see a story like that of Nicaraguan Sign Language, it reaffirms the belief almost all of them share that humans have an incredible—not a shamefully inadequate—capacity for language.

Nicaragua, like most poor countries, did not have well-developed support systems for deaf children. They were merely left to grow up as best they could, in small and scattered schools. They did not (as they did in richer countries) meet and form larger deaf communities and thus create families consisting of all or mainly deaf members communicating through sign language. In fact, there was no sign language for them at all. Deaf Nicaraguans, thus, were language-deprived.

In 1977, though, the first sizable school for disabled children (including deaf children) was built in Managua, a pet project of Hope Portocarrero, the wife of the then dictator Anastasio Somoza. Teachers tried to normalize the deaf students by teaching them to lip-read and speak Spanish. Signing, as a result, was discouraged, but students were allowed to gesture to each other when out of the classroom. The school’s work was interrupted by the Sandinista revolution in 1979 but reestablished when the leftist Sandinistas had taken control.

At first, the deaf children at the school, in their prime language-learning years (roughly the decade before puberty), had made ad-hoc pantomiming gestures. But over several years, these gestures developed remarkably. First the students began to approximate each other’s gestures, causing standard signs to emerge. These remained rudimentary until the next generation, when a new batch of young children came to the school and learned the system as their first language. This transformed Nicaraguan Sign Language from a pidgin to a creole. It now had utterly regular rules, capable of expressing anything any spoken language can express, and a body of native speakers who would transmit NSL to new generations. Fascinated linguists have had the chance, for the first time in history, to watch a language being born, literally, from nothing. One recent study showed that it is children still in their language-learning prime who innovate new features of the language like “spatial modulation.” (This involves making a series of signs in a particular unusual position—for instance, to the speaker’s left—to indicate that a string of verbs all refer to the same subject.) If children are the innovators—their learning of NSL made it a true language, and they are refining it—then even if “innateness” does not exist, the human brain’s language capacity is nonetheless truly extraordinary.

NSL was a stunning and unique piece of evidence for the human language ability. But for linguists, it was not entirely surprising. Many other new languages have been created in modern memory: “normal” creoles, such as Saramaccan (a Portuguese-English creole used in Suriname) to Tok Pisin (an English creole that is the official and most widely used language of Papua New Guinea). The “pidgin” origin may tempt the conclusion that these, too, are broken-down languages, but they have highly sophisticated grammars. Like Black English aspect-marking “he sick” and “he be sick,” many creoles make fine distinctions English does not.

But to test the alternative hypothesis, how would we know if one language was “better”—more sophisticated, more expressive, more logical—than another? Or one language cruder, less expressive than another?

Sticklers often deride language changes because they erode distinctions that were previously there. Using “infer” for “imply” robs the language of a neat verb, “infer,” which doesn’t have another ready synonym. “Awesome,” “terrific,” and “fantastic” once had clear connections to awe, terror, and fantasy, but have since been bleached into bland synonyms for “really good.”

Linguists give several answers. New words often step in (“awe-inspiring” now means what “awesome” used to). Context and additional words often provide the correct meaning of vague words or phrases (“I don’t mean ‘ha-ha’ funny but ‘weird’ funny”). The stickler reply is that this is unnecessary and impoverishing; a language that requires the support of context and extra words to make fine distinctions is an impoverished one.

Mark Halpern, the opponent of modern linguistics we met in the last chapter, sees a danger in increasing vagueness of language when words’ meanings shift or old words acquire second meanings: “When I shout ‘Fire!’ it is rather important that those addressed know immediately whether I mean ‘Run for your lives!’ or ‘Pull the trigger!’ ” Never mind that it is virtually impossible to imagine a real-world situation in which this ambiguity is possible.* Is Halpern right that a “good” language is one in which single words are packed with so much meaning that other words, grammar, and context aren’t required? If he is, then his native language and mine, English, is among the world’s worst languages.

Examples abound. The English verb is almost totally uninflected in the present tense; it merely adds “-s” to the third-person singular. (I speak, you speak, he speaks.) The Arabic present-tense verb has eleven distinct forms (a couple of forms do double-duty):

As is common in languages with rich conjugational endings, the pronoun isn’t required, since the ending alone shows whether the verb means “he writes” or “they write.” “Yaktubu” is a full sentence. English, by contrast, requires the support of a pronoun. But does this really make English impoverished and vague? Would Halpern and the rest of the “No vagueness!” battalions concede the crude inferiority of the English verb to its Arabic counterpart?

And speaking of pronouns, English is poor in that department too. Arabic has two “theys,” letting us know if the group is male or mixed (hum), or all-female (hunna). Arabic also distinguishes two (huma) from more than two (hum/hunna). But Arabic is itself impoverished compared to Kwaio, spoken in the Solomon Islands, which distinguishes not only singular, dual, and plural but singular, dual, paucal (a few), and plural (many). And it distinguishes “we” (you and me) from “we” (me and those with me, but not you). This handy distinction would head off many social awkwardnesses in English:

COOL KID: Uh, we’re going to the movie.

AWKWARD, OBLIVIOUS CLASSMATE: Great, I’ll grab my jacket!

But somehow we English-speakers get by with just seven pronouns to Kwaio’s fifteen.

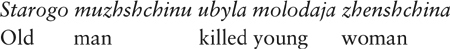

Case, like verbs and pronouns, is little marked in English. “He” is distinguished from “him,” but ordinary nouns are not marked, and no one seems to know how to use “whom” anymore. English lost a case-marking system that existed in the Beowulf era. And case marking can be handy: it allows for flexibility in word order, which can be usefully manipulated for emphasis: the Russian

means “A young woman killed an old man,” not the opposite. The case marking on both the old man and the young woman tells us who killed whom and allows us to put the surprising element, the identity of the killer, in the attention-grabbing spot at the end of the sentence. But mighty Russia must envy its tiny neighbor: Estonian has fourteen cases to Russia’s six. One word can convey “like the book,” “with the book,” “onto the book,” “out of the book,” and many others.

English looks simplistic in many other ways, too; it has no genders. Swahili has twelve. Tuyuca, mentioned earlier, has “evidentiality,” requiring the speaker to attach a verb suffix to verbs in a declarative sentence showing how the speaker knows what he is saying is true. English lacks that.

Then again, English has features that many languages lack. Black English is like Russian in usually leaving out “to be” in simple present-tense sentences:

He my brother. On moi brat.

English has both a definite and an indefinite article (“a”/”an” and “the”), putting it into a category with only about 20 percent of the world’s languages. It distinguishes “I speak,” “I am speaking,” and “I do speak” in the present, which most languages don’t do. (Ask any English learner how annoying this is to master.) And although orthography isn’t related to grammatical complexity, English has the most difficult alphabetic spelling in the world.

English is an “analytic” language. It has moved away from using suffixes and toward word order and auxiliary words (such as prepositions) to convey meaning. This change isn’t good, bad, or indifferent; it is just change. Other languages, such as Chinese and virtually all creoles, are more analytic still. Meanwhile, the “synthetic” languages lean heavily on word endings, from the ordinary (marking nominative versus accusative case) to the exotic (evidentiality, for example).

But all this counting up of complexities misses the point. Fetishizing the differences between languages—who makes finer-grained distinctions between this and that with word endings and who uses context or helping words—misses the forest for the (admittedly fascinating) trees. Every language can do pretty much everything, even if, contra the sticklers, grammatical endings change or disappear over time; even if words lose a specific meaning in favor of a more general one; even if straightforward mistakes catch on until nobody knows the original meaning of a word anymore. English speakers suffer no confusion from the fact that we no longer use the case endings on nouns that prevailed in Beowulf; we won’t suffer if we lose “whom” either. The same can be said of Spanish and French, which shed Latin’s case endings. Or the spoken colloquial Arabics, which get along with a fraction of the word endings found in the Qur’an. This kind of thing happens in every language, yet no language has ever declined in intelligibility. It’s just not a thing that languages do.

But doesn’t careful attention to language equal careful attention to facts and logic? Here the sticklers have an important point. As a teacher, I can verify that woolly and vague thoughts are usually badly expressed, and students with something vivid and interesting to say usually find a way to write them or say them well.

But the connection between thought, logic, and language doesn’t run clearly in the direction many sticklers think it does. And to address this point, we must address the famous—some would say notorious—Sapir-Whorf theory of language.

Briefly, Edward Sapir was an American linguist who studied American Indian languages, and Benjamin Lee Whorf, though not a professional linguist, extended and popularized Sapir’s ideas. In Sapir’s often-quoted words,

Human beings do not live in the objective world alone, nor alone in the world of social activity as ordinarily understood, but are very much at the mercy of the particular language which has become the medium of expression of their society. It is quite an illusion to imagine that one adjusts to reality essentially without the use of language and that language is merely an incidental means of solving specific problems of communication or reflection. The fact of the matter is that the “real world” is to a large extent unconsciously built up on the language habits of the group.… We see and hear and otherwise experience very largely as we do because the language habits of our community presuppose certain choices.

Whorf expanded this idea—that a person’s access to reality is conditioned by the language he speaks. Whorf himself became so known for this that the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis is often simply known as “Whorfianism”: other writings of Sapir indicate that he wouldn’t have gone as far as Whorf did. Famously, Whorf argued that, for example, the Hopi Indians of the American Southwest did not use the segmented, linear words for time common to the Indo-European languages. As a result, Whorf thought, the Hopi did not conceive of time in the same way that Westerners did.

It is an appealing notion, stimulating two popular beliefs that recur throughout this book: that language is fearsomely powerful and that languages differ exotically from one another (that is, they have different fearsome powers, and some languages are more powerful than others). If language is powerful enough to affect thought itself and languages differ vastly, then peoples themselves must be even more different than they seem on the surface.

The chief problem with Whorfianism is that it is, at least in its strong form, not true. Whorf presented not a single sentence of Hopi in his work. More detailed research on that language would take decades later to appear, in the 1970s and 1980s. It showed that the Hopi did indeed have time words like Westerners did, albeit in a different form. Other research confirmed that the Hopi were perfectly capable of thinking about time in the same way Westerners did. Whorf’s modern defenders note that his claims were exaggerated by his followers. He died young, having not completed much of his work and thus leaving his ideas open to misinterpretation.

Fair to the man himself or not, “Whorfianism” is now a byword for misguided thinking among many linguists. It isn’t hard to debunk the strong version of it. It is quite easy to think of a concept that you lack a word for. This was the thinking behind, for example, The Atlantic’s lighthearted back-page column “Word Fugitives,” which used to invite readers to send in newly coined words for common problems and situations that don’t have one. December 2008, for example, featured

a term for the “irresistible impulse” to rearrange the dishes in a dishwasher that someone else has loaded. According to zillions of readers, that’s obsessive compulsive dishorder. Another zillion, give or take, pegged it as redishtribution—or dishorderly conduct, redishtricting, dishrespect, or dish jockeying.

If strong Whorfianism were true, how could people formulate the concept without the framing it in language first? How would legitimate new words emerge? It’s obvious that once we need to refer to something often enough, we find it useful to coin a word for it, so language and thought are clearly bound together. But isn’t it clear that the thought precedes the word?

Weaker versions of Whorfianism, however, may be true. The existence of certain traits in a language might incline speakers one way or another, rather than restricting or strongly defining what they can or can’t think. Lera Boroditsky of Stanford University has braved many linguists’ disdain of Whorfianism to do some research on the subject. She has argued, for example, that Mandarin-speakers think of time as a vertical line, whereas English-speakers think of it as a horizontal line. Whereas we say “last month,” they say “down month.” And if you ask a Mandarin-speaker, pointing to a spot in front of him, “This is today. Where is tomorrow?” he will be more likely to point above that spot. English speakers will point in front of it (i.e., farther away from the speaker).

But is this strong Whorfianism or merely an interesting difference in metaphorizing? Time is not space, and so when we are forced to use space metaphors to describe time, it’s hardly surprising that if we use an up-down metaphor in speech (“up month” and “down month”), we’ll use a vertical motion in physical pointing, with the same going for horizontal metaphors and horizontal movement. Those looking for fascinating differences between speakers of different languages will need a bit more.

Boroditsky gets more concrete when she looks at several languages closer to home. German and Spanish both assign all nouns a gender. (German has masculine, feminine, and neuter, while Spanish has only masculine and feminine.) Mostly these genders are arbitrary. But since they have a surface relationship to sex differences, Mark Twain once noted with amusement that “in German, a young lady has no sex, but a turnip has.” (Mädchen is neuter, while Steckrübe is feminine.) In many languages, even living things don’t always always have the same grammatical gender as their natural gender would suggest.

Genders may be arbitrary, but Boroditsky found that they can still affect how people think about things. To test this, she collected a set of words that were masculine in Spanish but feminine in German or vice versa. “Key,” for example, is masculine in German (der Schlüssel), and when asked to describe a key, Germans were more likely to choose words such as “hard,” “heavy,” “metal,” and “useful.” Spaniards, who use a feminine word for “key” (la llave), were more likely to associate it with “golden,” “tiny,” “lovely,” and “intricate.” But this is not German toughness; when Germans have a feminine word, such as “bridge” (die Brücke), they are more likely to describe it as “beautiful,” “elegant,” and “peaceful.” Spaniards, who use a masculine word (el puente), choose words such as “strong,” “sturdy,” and “towering.” More interesting still is that this testing of Germans and Spaniards was done in English. Once a key was associated with masculinity, the prejudice persisted across Germans’ minds even in a foreign language. Boroditsky also found that German painters tend to paint death as a male figure—unsurprisingly, as death is masculine in German. Russian painters make death female, as does their language.

In perhaps her most tantalizing piece of research, Boroditsky found that the Kuuk Thaayorre of Australia have no words for “left” or “right,” “front” or “back,” all words related to the position of the speaker. Rather, the Kuuk Thaayorre refer always and only to fixed cardinal directions. So they will say, for example, “You have an ant on your southwest leg” and “Move your cup a little to the north-northeast.” When they greet, instead of “Hello,” they ask, “Where are you going?” and the reply will be something like “South, in the middle distance.” Boroditsky marvels that they stay constantly oriented. When she asks a roomful of Stanford or MIT professors to close their eyes and point southeast, few of them can. But the average five-year-old Kuuk Thaayorre–speaker can do so. And this isn’t merely because their living conditions—geography, lifestyle, and so on—require staying oriented. Boroditsky points out that groups living near the Kuuk Thaayorre, in nearly identical conditions but without this feature in their languages, also lack the ability to stay constantly oriented.

Boroditsky’s work puts her in a camp of neo-Whorfians. She strongly believes that different languages train the mind in different ways. Boroditsky rejects the notion—prominently expounded by Noam Chomsky, Steven Pinker, and others—that human language is fundamentally a single phenomenon, with interesting surface variations but much deeper universals.

But the neo-Whorfians argue that language steers—it does not govern—what we perceive and think. Some languages, such as Chinese, have no word for “brother,” only “older brother” and “younger brother.” These languages surely force people to pay more attention to birth order. But this is far from saying that languages without this distinction pay no attention to birth order.

And when it comes to the equality of languages, Boroditsky feistily agrees with the universalists: there is simply no such thing as a “better” or “worse” language. English, by most measures of “complexity,” is simple. Yet few of its defenders would argue that its lack of extravagant grammar leaves its speakers unable to think with complexity and subtlety. The academic debate over Whorfianism and universals will go on, often among psychologists and philosophers as well as linguists.

While linguists debate exactly what Whorf really meant and whether findings such as Boroditsky’s should revise their traditional disdain for certain Whorfian claims, in a furious and controversial academic debate, many, perhaps even most, outside the academic community unthinkingly accept a form of Whorfianism even though they have never heard the man’s name.

There are two versions of pop Whorfianism out there, both misguided and both political. The first is, alas, represented best by one of the finest writers in twentieth-century English letters, George Orwell.

Orwell, born Eric Blair, called himself a “democratic Socialist” (always capitalized thus in his writing). Though a man of the left who volunteered with the Republicans in Spain, he was stridently anti-Soviet and anti-Communist, modeling his most famous character, Big Brother, after Stalin. Left or right, he hated any kind of totalitarianism.

At the end of his 1948 novel Nineteen Eighty-four, Orwell added an appendix on “Newspeak,” the propaganda-laced language designed by the totalitarian state of Oceania. Newspeak was to gradually replace English (Oldspeak), and it was described as the only language that shrank in vocabulary and expressiveness every year. Every concept would have only two valences, positive and negative, and thoughts such as “freedom” and “rebellion” would eventually vanish from the lexicon entirely.

This was a form of pop Whorfianism. In Orwell’s conception of Newspeak, if you couldn’t put a name on something, you couldn’t think it. This is clear when he writes:

The purpose of Newspeak was not only to provide a medium of expression for the world-view and mental habits proper to the devotees of Ingsoc [English Socialism], but to make all other modes of thought impossible. It was intended that when Newspeak had been adopted once and for all and Oldspeak forgotten, a heretical thought—that is, a thought diverging from the principles of Ingsoc—should be literally unthinkable, at least so far as thought is dependent on words.… A person growing up with Newspeak as his sole language would no more know that equal had once had the secondary meaning of “politically equal,” or that free had once meant “intellectually free,” than for instance, a person who had never heard of chess would be aware of the secondary meanings attaching to queen and rook. There would be many crimes and errors which it would be beyond his power to commit, simply because they were nameless and therefore unimaginable.

In one phrase, “at least so far as thought is dependent on words,” Orwell begged the question. Thought isn’t dependent on words. At most, even if more research confirms what Lera Boroditsky suspects, language and thought interact far more subtly and interestingly than the one-way street—“thought is dependent on words”—that Orwell proposed.

And even if—to take a science-fiction book a tad too seriously—Oceania succeeded in banning all the undesirable words overnight, they would never truly disappear. They would almost certainly be reinvented. After all, Nicaraguan deaf children did it beginning with no language whatsoever. And as we will see in a future chapter, the re-creators of modern Hebrew took the limited stock of words in the Bible and the Talmud and created a modern language with words for everything from “telephone” to “clitoris.” Language is simply far too vital, and too fired by its own internal logic, for any state ever to chase out “undesirable” words for good. We need them, and if we didn’t have them we’d quickly create them, again and again if necessary.

The more serious version of Orwell’s Whorfianism preceded Nineteen Eighty-four: his celebrated 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language.” In it, Orwell offered six memorable rules of writing, quite near the beginning of the essay, rules that would have made Strunk and White proud. And it has to be said that they are rules that, if borne in mind by the apprentice writer, will improve most prose.

(i) Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

(ii) Never use a long word where a short one will do.

(iii) If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

(iv) Never use the passive where you can use the active.

(v) Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

(vi) Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

For Orwell, this had political consequences. In an earlier essay, “Why I Write,” he described in himself (quite accurately) one of the characteristics that made him a good writer: “a power of facing unpleasant facts.” For him, this was connected intimately with vigorous, clear writing. Lazy writing—euphemism, cliché, and dead metaphor—all led to lazy thinking. This lazy thinking, in turn, made both writers and readers susceptible to political manipulation. Those who don’t pay attention to the abuse of a euphemism such as “pacification” for “gunning down rebellious villagers” are making Big Brother’s job easier. A lazy writer who didn’t try to look freshly at the world around him every day and find arresting new language to talk about it surrendered the weapons of the struggle—words—unilaterally.

But Orwell, pointed and brilliant thinker that he was, fell into the same trap as so many of his fellow language grouches. The first sentence of the essay begins “Most people who bother with the matter at all would admit that the English language is in a bad way.” He was right that legions of people who think about English think it’s “in a bad way.” But he, the great facer of unpleasant facts, was fortunately not describing a fact but instead just indulging our friend the age-old, worldwide habit of declinism. Remember that Swift thought that English had reached a near-terminal decline in 1712. The Fowler brothers complained of hazy imagery, foreignisms, and jargon in 1906’s The King’s English, published when Orwell was three. Henry Fowler repeated many of the same complaints in 1926’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage, when Orwell was a young imperial policeman in Burma. Lynne Truss says the same today. The English of Orwell’s 1946 was not “in a bad way,” unless the English of 1712, 1906, 1926, all were too, and today’s as well.

Beyond succumbing to the old temptation of linguistic declinism, Orwell made a conceptual mistake. He may never have heard of Whorf, but somewhere he got the idea that language precedes thought. To be sure, he said that writers should “let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way around.” But elsewhere in “Politics and the English Language” he wrote that “if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought,” as if the ruined state of “the English language,” whatever that would mean, was making people dumber.

Once again, with emphasis: the language, including its grammar, pronunciation, vocabulary, and common phraseology, is not mainly responsible for the content of people’s thoughts. If people were spouting a lot of political poppycock in Orwell’s time, that is because that was an ugly time in global politics, not because English or any other language had gone downhill. How, for example, did he think Hitler and Stalin had come to power, in nations that possessed two of the world’s greatest written traditions? How on the other hand, if English was so debased, had Britain and the United States found the steel to defeat the axis? Orwell, a keen student of both fascism and communism, should have known that it wasn’t the state of German or Russian that had weakened Germany and Russia for dictatorship; it was the impoverishment and humiliation of the people, who believed the nonsense fed them because they were angry and afraid, not because their language was softened up. Orwell, a great writer, can be forgiven for thinking language is the most important thing on earth. But sometimes people just let themselves be misled, and language has nothing to do with it.

Take a modern piece of linguistic-political legerdemain. Is the problem with the following sentence linguistic?

The British Government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa.

These sixteen words don’t violate any of Orwell’s rules. They are clear English—he might have preferred something less fancy than “significant quantities,” but all in all, they are straightforward enough. Millions believed them. The problem with this statement, spoken by George W. Bush while making the case for the war in Iraq in 2003, is that it was deliberately misleading: using the verb “learned” made it sound as if the British government were certain that Saddam had sought uranium in Africa. In fact, Britain’s intelligence services only suspected it, with a degree of uncertainty intrinsic to intelligence work. Bush’s listeners believed it, but not because they didn’t know how the verb “learned” works. They wanted that war, and they trusted Bush to give them good information—and those eager to believe Bush included many bright people who would never dream of leaving a modifier dangling. The problem of political credulity, whatever its provenance, isn’t primarily a problem of language.

But when people are losing political arguments, it’s too easy to blame the language itself. This isn’t limited to the right or the left. For example, George Lakoff, a left-wing linguist at the University of California at Berkeley, thinks Democrats have lost many of the modern political battles because they are “out-framed” by Republicans, who get their preferred terminology for things repeated (and internalized) by voters. Lakoff has made a one-man industry of convincing Democrats to reframe things like “taxes” as “membership dues,” a battle he has yet to win.

From the right, meanwhile, Mark Halpern, the stickler and Orwell admirer, hopes to stop the cultural rot he sees coming from the left by promoting his brand of sticklerism, because

becoming sensitive to mere solecisms increases one’s sensitivity to language in general, and is a big step in learning to detect and resist dishonest and tendentious language.

This is partly true, but not in the way Halpern thinks. Of course being sensitive to language makes people more likely to detect and resist dishonest language. This isn’t because language has some mythical power to make people smarter. Being sensitive to science is a big step in learning to detect and resist dishonest language. Being sensitive to history is a big step. Being sensitive to political philosophy, logic, economics, and even mathematics is a big step, because all of these things are learning, and knowledge creates aware and critical citizens. There is nothing magical about language in this regard. Knowing the difference between “infer” and “imply” is no more likely to create a skeptical, bullshit-detecting citizen than knowing the atomic weight of uranium or the capital of Niger. Smart people of all types don’t tend to be hoodwinked so easily.

Halpern is right that Americans (and most other nationalities) are paying too much attention to the wrong things much of the time. Everyone could spend more time with a book and less with The Biggest Loser on television. But he is wrong in his pseudo-Whorfian notion that paying attention to traditional grammar rules and usage shibboleths gives you a kind of talismanic defense against dishonesty. In fact, blindly memorizing rules is just the opposite of the kind of flexibility, empiricism, and fingertip-feel that a characterizes a mind resistant to dangerous dogmas. Halpern is joining a long lineup of people who have begun with decent ideas (“Pay attention to language use”) and recruited them to silly political ends: learn prescriptivist rules, or the terrorists and communists will win.

Orwell is an example of political Whorfianism within one language: speak and write proper English, and your political acumen will improve. A related phenomenon is Whorfianism between languages and dialects. We’ve already seen the dismissal of Black English as incapable of being a vehicle for higher thought. We see the same around the world. Most people today are usually too polite to dismiss the expressiveness of other languages. But they do still have a habit of seeing one—nearly always the prestige variety of their own language—as more equal than others.

The French, linguistic nationalists par excellence, are famous for sharing this kind of nationalistic Whorfianism. In 2007 a group of French activists made an outrageous push to have their language recognized as the sole legal language of the European Union. The effort went nowhere. Since the EU’s founding, all national official languages had the right to be declared official EU languages.* The notion behind official equality is a sound one. How are (say) Finns to connect with “their” European Union if their native Finnish is not an official language? The twenty-three-language situation is unwieldy but politically necessary.

Where, then, did the French get the preposterous idea of making French the sole legal language? The culprit, again, is pop Whorfianism. Maurice Druon, the “perpetual secretary” of the French Academy until his death in 2009, (he retired in 2000, but Academy membership is permanent), said that, of course, “all languages are equal.” But he went on to contradict this completely by saying that

The Italian language is the language of song, German is good for philosophy and English for poetry. French is best at precision, it has a rigor to it. It is the safest language for legal purposes.… The language of Montesquieu is unbeatable.

Oddly, the French were supported by a former Romanian prime minister and a former Polish foreign minister. Belief in the superiority of a language for this or that task is usually but not always limited to one’s own language.

It’s hard to believe that any adult could take these notions seriously, but many people do. The superiority of German for philosophy, in particular, is something I’ve heard from serious Americans, too. I’m not sure, though, where Druon got the idea that English is best for poetry. France and Germany certainly have their share of great poets. Perhaps he was being devilish; saying a language is good for poetry could be a way of saying it is pretty but not so serious.

In 2008, the French National Assembly (the main house of parliament) considered a brief addition to the constitution: “The regional languages are part of the patrimony of France.” The statement, not only harmless but obvious, resulted in an outcry. This is because French has a near-mythical status as the very spirit of the French nation. In arguing against the proposal, one opponent of the proposal, Jean-Claude Monneret, wielded this argument:

Not all languages have the same dignity. Even if one is a linguist—as I am—and convinced of the necessary pluralism and survival of all languages, one can’t put on the same level a great language of culture and an impoverished dialect. Is there a Rousseau in Occitan, a Tocqueville in Basque, a Balzac in ch’ti, to allude to a recent film, a Stendhal in Breton, a Montesquieu in Catalan?

“Impoverished dialect” is strong language for someone who claims to support the regional languages. But Monneret seemed to find it self-evident that Catalan, Basque, and the others were not “dignified” because they had not produced a Rousseau or a Tocqueville.

Could this possibly be because those languages are not up to the task? Certainly not. The reason French has its Tocquevilles and English its Miltons and German its Goethes is because French, German, and English were big languages, undeniably: the main languages of some of the most powerful nations in the world. And the English, French, and German we know today are what they are because, largely, of historical accident. Had Martin Luther come from Hamburg, he might have translated the Bible into something more like Niederdeutsch (“low German” from the northern flatlands, closer to Dutch), and that, not Hochdeutsch (“high,” now standard, German) would be the prestigious language of everyone from Schiller to Wittgenstein. The same might be said for the southeastern dialect that became standard English or the Île-de-France French that became standard French. Their supremacy is political, not linguistic.

But Monneret has a point. Once language does become a standard, a self-fulfilling prophecy begins. As the prestige language of the state, the standard becomes the vehicle of education and learning. This produces a body of literature in the standard for the simple reason that even if Montesquieu or Rousseau had spoken Basque as their first language, they would have had to be unambitious, cantankerously contrarian, or highly regionally nationalistic to write in Basque. Nobody would have read their work outside the region. So Monneret’s argument is correct but uninteresting: of course the great authors he mentioned wrote in standard French. This tells us nothing about the qualities of the language itself and more about the number of people who can, and would, read a great novel in Basque.

That self-fulfilling prophecy, however, muddies our picture of linguistic equality. Once there comes into being a body of literature in a language, a literary style follows. Lexicographers compile dictionaries, keeping rare words and stylistically useful synonyms alive. So a prestige language may have more resources for a writer to draw on than another. And that is what makes those languages’ admirers think that they are superior to any other: the flexibility and refinement of vocabulary, in particular, are enticing.

Many people share this idea that a language is “sophisticated” to the extent that it has a large vocabulary. In this view, language is simply a store of words—the thicker the dictionary, the better the language. The kind of person who believes this usually delights in etymology or the collection of linguistic curios, rare words that no one ever uses in natural conversation. Does anyone really ever say, “I have triskaidekaphobia” instead of “I have a fear of the number thirteen?” The most obvious showing off here is of the speaker’s vocabulary—see how many words I know? But below the surface is a pride in the treasury of words itself. See how many delightful and rare words my language has?

This thinking—“language as a storehouse of words”—misleads in a number of ways. Some languages, of course, seem to have more words than English, because they routinely coin single words where English uses a combination of two or more. German is famous for this. Foreign learners, like Mark Twain writing in “The Awful German Language,” gnash their teeth (or laugh) over words like Unabhängigkeitserklärungen (“declarations of independence”) and Waffenstillstandsunterhandlungen (“cease-fire negotiations”). But the fact that German coins long words while English uses a phrase (which functions grammatically just like German’s compounds) doesn’t mean, in any real sense, that German has a richer vocabulary. It means little more than that Germans have less recourse to the space bar than English-speakers do. Other “agglutinating” languages, whether Turkish or Inuit, can cram together so many different meaningful pieces (“morphemes,” in the linguist’s argot) that the stock of words is virtually infinite. But that doesn’t make Turkish or Inuit richer than English.

That said, languages can, in fact, have more or less rich vocabularies. This usually means one of two different things. One is that languages that have had a great deal of contact with other languages will absorb foreign words and (in the happiest circumstance) keep their own. This will result in sometimes useful synonyms; think of the English groupings that come from the conquest of England by the Normans and the Vikings. This is how we have kingly (Anglo-Saxon), royal (French), and regal (Latin). This gives writers, especially (since they can choose their words at leisure) a stylistic flexibility that languages less rich in near synonyms lack.

The other way in which the European languages really are richer than the average isolated language of New Guinea is their technical vocabulary. Since the modern sciences by and large come from Europe and North America, the vocabulary of chemistry, physics, and so on tends to be drawn from the European languages, particularly English (though English originally drew them from Latin or Greek).

This, again, is true but uninteresting. Of course English is replete with technical terms while Kuuk Thaayorre is not. But this isn’t a comment on the strengths of English or the weakness of Kuuk Thaayorre. It is a comment on the success of Anglophone scientists and the relative dearth of Australian aboriginal Nobel Prize winners.

Meanwhile, lack of scientific vocabulary need not hold a language back. There are two options for making up the shortfall. A country seeking to elevate its national language to a status where it can be used (say) for university teaching and research need only mint words. It can either bring them over from the original European language, making allowance for the native sound system (Arabic did this with fiziya’, physics), or by coining a word from native roots (Arabic ahyia’, “biology” from hayaa, “life”). Sometimes both happen: the “official” word for “computer” is hasoub, from a native root. But most Arabs simply say, and sometimes write, kombyuter. Hungarian, Hebrew, and Turkish are just some of the languages that have been artificially, but successfully, enriched by this mixture of borrowing and native invention. It takes time and expertise, but it is a relatively straightforward process for most languages.

So the real test of a language isn’t whether it allows its speakers to discuss any technical matter under the sun. Most people can’t discuss the finer points of cosmology or particle physics in any language. The question we should ask, before declaring one language or dialect inferior, is whether it is capable of expressing the full range of human thought; not whether it has a thick enough dictionary but whether it has a structure that can accommodate these demands as long as the needed words are either available, borrowed, or invented.

If we look to grammar, we find that some languages have myriad affixes that make distinctions that would rarely occur to an English-speaker. But we have seen—despite sticklers’ complaints that languages can lose their ability to make important distinctions if they are used “carelessly”—that languages that lack inflection are no less sophisticated or supple.

English is one such language; though it certainly has its complexities, it is fair to say that it is simpler than most of its Germanic cousins. Yet it is the most successful language on Earth. Mandarin Chinese is another. Though the writing system is absurdly complicated, this is a historical oddity; the modern spoken language is in fact far simpler than the other “dialects” of Chinese (actually languages, a debate taken up in chapter 6). In word endings, number of tones, number of overall sounds, and many other areas, Mandarin is the simplest of its family, simpler, too, than the classical Chinese that it replaced in the republican era at the beginning of the twentieth century. Yet Mandarin has been plenty successful, used by more people than any other language on Earth and serving as the official language of a rising political and economic power to boot.

In fact, John McWhorter argues that successful languages tend to be simplified by their success. To put it more exactly, languages such as English, Mandarin, and Arabic, because they have been learned by many millions of people as a second language over the course of their history, have shed inflections in favor of “analytic” structures. Twelve genders, as in Swahili, or fifteen cases, as in Estonian, put a huge load on an adult second-language learner. Languages don’t spread because they are simple and flexible (as some think true of English). The causation runs the other way around. They are forced to be simpler and more flexible when they spread. English was simplified—the stickler would say “dumbed down”—by its history of contact: between the Anglo-Saxons and the Celts, Vikings, and Norman French they came into contact with. And it seems to happen to other languages too: a statistical analysis of thousands of languages found that languages spoken by large numbers of people have relatively simpler grammar, in particular the prefixes, suffixes, and so forth that distinguish, say, Latin from English. Languages shake off bits and pieces as they grow and spread.

Sticklerism and nationalism are thus, though they so often go together, a bad fit. There is no way to seriously proclaim the overall superiority of this language or variety over that one. We can merely say that some languages have been elaborated—their grammar formalized, their vocabulary stored up—in such a way that makes certain kinds of literary and scientific writing easier. Other languages can be banged into shape for these same tasks. But we often see languages getting simpler as they succeed. More people use, and change, the rules. Sticklers may not like it, but shedding unnecessary bits of grammatical baggage may be necessary for a language to spread in the very long run. Success has its price.

* Okay, two mafiosi are in a crowded theater; the boss tells his lieutenant to shoot their mark, but when he shouts “Fire,” the theatergoers stampede out, killing the two gangsters. The mark, miraculously, survives.

* The Irish waited a few decades before insisting that Irish be made an EU language. The Luxembourgers, rather more sensibly, have never insisted on making their third official language, the little-known Letzeburgesch, official at the EU level.