I

Ancien régime

In early autumn of 1793, officials of the French National Convention called on Antoine Lavoisier at his private residence in Paris: 243 boulevard de la Madeleine. A block to the west along this fashionable street, work had been suspended, since 1791, on the church Saint-Marie Madeleine, designed in the style of the Greek Parthenon. From the unfinished classical portico, the view south was open down the rue Royale to the Place de la Révolution, where the guillotine would soon be installed. Dr. Guillotin, like Lavoisier a member of the Parisian scientific elite, had meant the device to be a humane and civilizing reform of the brutality of axes and ropes; he would be as appalled as anyone to see his idea evolve into one of the most horrifying weapons of terror that the Western world has ever known.

The officials had come, on behalf of the dread “Committee of Public Safety,” to search and seize Lavoisier’s papers; in the end they found nothing suspect but some correspondence in foreign languages (English and Italian) from fellow scientists: Lazzaro Spallanzani, Joseph Priestley, Joseph Black, Benjamin Franklin. Lavoisier asked and was granted permission to apply his personal seal to the seized bundle. Probably he feared that more dangerous documents might otherwise be planted in the package by his enemies, though the report filed on the procedure stated that “it is not from distrust that he solicits this precaution, but for the sake of order.”

The date, according to the French Revolutionary Calendar, was 24 fructidor of the Year One, though neither Lavoisier nor anyone else knew it. So far as they were all concerned, it was September 10, 1793. The French Revolutionary Calendar, though dated from the establishment of the French Republic on September 22, 1792, was not proclaimed and adopted until October of 1793. Therefore, the Year One existed only in retrospect; no one experienced it directly. And yet it mattered. Before the Year One, Lavoisier’s life and career had been tidily woven into the social fabric of the Bourbon monarchy. From this day forward his life and work would be reexamined in the new and dangerous context of revolution and terror.

The French Revolutionary Calendar was intended to detach the authoritarian hand of religion from the measurement of time—and to purge the Julian calendar of mathematical eccentricity. The reformed calendar operated on base ten, dividing each month into three ten-day cycles, and each day into ten periods of one hundred minutes worth one hundred seconds apiece. Lavoisier himself was an advocate of the reformed calendar, and in 1793 he was actively at work on a parallel reform of the system of weights and measures; this decimalized method of measurement proved much more durable than the Revolutionary Calendar and remains standard, as the metric system, today. On 24 fructidor of the Year One, another of Lavoisier’s scientific colleagues, Antoine-François de Fourcroy, came with the other officials to boulevard de la Madeleine to repossess instruments Lavoisier had been using for the weights and measures project—a bad omen, for Lavoisier had calculated that his participation in this public project would ensure his safe passage through the turbulent times.

If Lavoisier had properly understood the danger that the radical new social context of the as-yet-undeclared Year One presented him, he would perhaps have fled the country. Apparently he failed to perceive the extent of his risk, although in other contexts he understood—better than any other scientist of his time—the crucial importance of radical changes in point of view. What Lavoisier called le principe oxygine, whose discovery would ensure his permanent and prominent place in the history of science, had been discovered by others before him: Joseph Priestley, who thought of it as “fixed air,” and Carl Wilhelm Scheele, who called it “fire air.” Lavoisier’s radical act was to understand and define the not-altogether-new gas as oxygen, thus placing it in an entirely new context from which the whole of modern chemistry would begin to evolve. His was an extraordinary exercise in the power of naming.

IN THE YEARS before the French Revolution, Lavoisier’s genius for order had found many applications outside his purely scientific research. In 1788, he held five important public posts at once, including the directorship of the Gunpowder and Saltpeter Administration and a place on the board of the Discount Bank, which gave him an influential role at the center of French national finance. By 1790, his omnipresence in public affairs, along with his very considerable wealth, made him an attractive target for the radical left. In January 1791, the Jacobin journalist Jean-Paul Marat assailed him in the pages of L’ami du peuple: “I denounce to you the Coryphaeus of the charlatans, Master Lavoisier, son of a land-grabber, apprentice-chemist, pupil of the Genevan stock-jobber Necker, a Farmer General, Commissioner for Gunpowder and Saltpeter, director of the Discount Bank, secretary to the King, member of the Academy of Science, intimate of Vauvilliers, unfaithful administrator of the Paris Food Commission, and the greatest schemer of our times.”

Marat’s denunciation sprang from old resentments and rivalries; in 1779 Lavoisier had helped discredit Marat as a scientific charlatan—on behalf of the French Academy of Sciences. In the leveling climate of 1791, the very existence of national academies for the sciences, literature, and culture could be made to seem culpably elitist, and the patent of nobility that Lavoisier’s father had purchased for him as a wedding gift in 1771 had very much ceased to be an asset. But his fatal point of vulnerability, the one that brought the commissioners to his house on boulevard de la Madeleine, was what had been his most lucrative day job—working for la Ferme Générale, or the General Farm.

For centuries, the collection of French taxes had been leased or “farmed out” by the French monarchy to private investors, who guaranteed the Royal Treasury fixed sums for the period of each lease, then took their own profit or loss from the taxes they could collect. By the end of the seventeenth century, the “tax farm” had swollen into a behemoth with thirty thousand employees. Late in the eighteenth century, the French government had become deeply dependent on the General Farm to obtain credit and service a rapidly growing national debt.

The General Farm was managed by a corporation of between forty and sixty partners when Lavoisier bought into it in 1768. The price of a full partnership that year was 1,560,000 livres; at the age of twenty-four, Lavoisier bought a one-third share from the elderly tax-farmer Baudon, who was seeking an assistant, for a down payment of 68,000 livres. He approached the business of tax collection with the reformer’s zeal he brought to almost all his activities, but even his most enlightened innovations tended to put new and unwelcome pressures on French taxpayers. The General Farm was no more popular than any tax authority in any other time and place, and probably less popular than most. The organization collected a tax on salt (gabelle) and another on alcohol and tobacco (aide), along with customs duties (traites) and duties on goods entering Paris from elsewhere in France (entrées). Evasion of all of these taxes through smuggling and other fraud was epidemic, and harsh punishment for such offenses increased the general distaste for the Farm. Moreover, accusations of profiteering were well founded.

The General Farm was abolished, amid widespread charges of mismanagement, in 1791. Lavoisier had resigned his position not long before; however, there was a demand in the French National Convention for an investigation of the Farm’s affairs reaching all the way back to 1740. The Farm’s assets were supposed to be liquidated and added to the national treasury, but this procedure kept getting pushed to the back burner by a series of political crises, as the Farmers, or ex-Farmers, were accused of stalling. By the fall of 1793, as the Reign of Terror commenced, impatience to resolve the matter of the General Farm (and collect the proceeds) had become extreme. Lavoisier was only one among many erstwhile Farmers to have his papers searched and seized.

Participation in the General Farm made Lavoisier one of the most prosperous members of the bourgeois class that grew and thrived during the last two decades of Bourbon rule. By 1786 he had turned a total profit of 1.2 million livres—the equivalent of 48 million in twentieth-century U.S. dollars. His manner of living was not ostentatious for a man of such wealth; a financial declaration for 1791 lists six household servants (one cook, one chambermaid, one coachman, and three lackeys)—a fairly small staff, considering the time and his position, though he also owned a 1,400-acre country estate, Fréchines, in the Loire Valley, and another 254 acres at Villefrancoeur.

Lavoisier’s career in the General Farm furnished him an excellent income, while leaving much of his time free for science and other pursuits. Taxes, in fact, supported his research—an abnormality for the period. In eighteenth-century France, science might be a vocation, but it was not much of a livelihood. Public financial support for science was scant; aspiring scientists had to bear the cost of their own research programs. Lavoisier, whose family background had been relatively modest, used his profits from the General Farm to equip one of the most sophisticated—and expensive—laboratories in Europe.

ANTOINE LAVOISIER’S great-great-great-grandfather was a courier riding postal relays for the Stables of the King. His great-great-grandfather became master of a relay station and hostelry in the market of Villers-Cotterêts, a town some fifty miles northeast of Paris. His great-grandfather, Nicolas Lavoisier, was a bailiff in the local court system and prospered well enough to own several houses in the town. Nicolas’s son, the chemist’s grandfather, became an attorney in the court and married the daughter of a well-to-do notary in the town of Pierrefonds. Their firstborn son, Jean-Antoine Lavoisier, was sent to Paris to study law. On the retirement of his mother’s bachelor brother, Jean-Antoine inherited his uncle’s place as a solicitor in the Parlement de Paris: the highest court of the ancien régime. It had taken the Lavoisier family over a century to complete this upwardly mobile trajectory to membership in the newly constituted professional class of robins—“men of the robe,” or lawyers.

Along with his post, Jean-Antoine inherited his uncle’s house in the Marais district of Paris, and a bequest of forty thousand livres. He found a good match in Emilie Punctis, the reputedly beautiful daughter of a well-connected bourgeois family that had made a modest fortune as butchers. Through careful investment in land, Jean-Antoine increased the family wealth—such were the grounds, however slim, for Marat’s description of him as a “land-grabber.”

The Lavoisiers’ first child, Antoine, was born on August 26, 1742, in the house of Jean-Antoine. A daughter, Marie Marguerite Emilie, followed two years later. When Emilie Lavoisier died in 1748, the widowed Jean-Antoine moved with his children, aged five and three, into the Punctis household. There, the children were cared for by their unmarried aunt, Constance Punctis, until Marie Lavoisier died, at the age of fifteen. Antoine Lavoisier, who would eventually die childless, was to be the last of his line.

A childhood marked by these losses left young Lavoisier quiet and sober, preferring study to play. At the age of eleven he enrolled in the Collège des Quatre Nations, where his father had earlier been schooled. Informally known by the name of its founder, Cardinal Mazarin, the Collège Mazarin occupied a magnificent domed building, directly across the Seine from the Louvre; today, as the Institut de France, the structure houses Lavoisier’s papers, with other archives of the Academy of Sciences. The family plan was for Lavoisier to follow his father into a career at law. At the Collège Mazarin, he tried his hand at literature, attempting a drama in the style of Rousseau’s La Nouvelle Héloise. In 1760, the year his sister died, he won a second-place prize for an essay (unfortunately lost) on the question, “Whether rectitude of the heart is as necessary as precision of intelligence in the search for truth.”

Lavoisier’s first exposure to chemistry came from his school’s instructor, Louis C. de La Planche, but a more important influence during those years came from l’Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille, an astronomer and mathematician whose observatory was on the grounds of the Collège Mazarin. Lacaille had taken the radical step of publishing his own algebra and geometry textbook in French, deeming it superior to the customary Latin. With the aid of Diderot and the other Encyclopédistes, eighteenth-century French was indeed crystalizing into the most lucid of the European languages, the ideal medium for works of pure reason. Lavoisier, who along with astronomy learned calculus and elements of Newtonian physics from Lacaille, did not miss this lesson. His liking for rational order in all things is grounded at this point; later on he would write, “I was accustomed to that rigor of reasoning which the mathematicians put into their works”—and especially the rigorous, step-by-step procedures of geometrical proof.

Lavoisier left the Collège Mazarin in 1761 and enrolled in the Paris Law School, yielding to his father’s argument that the sciences were an admirable leisure activity but did not amount to a profession. He was dutiful in his study of law, but more passionate in the scientific education he pursued at the same time. During his law school years he studied mineralogy with Jean-Étienne Guettard, a geologist in the Academy of Sciences who, though a self-proclaimed misanthrope, was also a regular guest in the Punctis household. At the Jardin du Roi, he studied botany with another well-known academician, Bernard de Jussieu, and took chemistry courses from Guillaume-François Rouelle. If Lavoisier had any taste at all for the fleshpots of Paris during those years, his double program of study left him no time for them; he was retiring to the point of reclusiveness, reputed to pretend illness from time to time to avoid social obligations. A friend of his father’s, M. de Troncq, sent him a bowl of gruel with an ironic admonition: “regulate your studies, and believe that one more year on earth is worth more than a hundred in the memory of men.”

In 1764 Lavoisier received his legal degree and was admitted to the Parlement de Paris; however, he would never practice law. At the tender age of twenty-one, he had already begun to plot a course toward membership in the Academy of Sciences. The Academy had been officially established a century before by Louis XIV’s chief minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert (who was also responsible for the consolidation of the General Farm into a single organization), in order to create a formal framework for the community of French scientists that had so far evolved organically. Supported by royal patronage, the Academy’s mission was to pursue both pure and applied science—to seek the prestige of discovery along with the material gains of scientific practice. Internally, the Academy functioned as a meritocracy, rewarding and promoting those whose contributions to science were strongest. Externally, it had the authority and the responsibility to validate or discredit new scientific discoveries and theories that were proffered to the public; by the mid-eighteenth century it was the ultimate arbiter of scientific progress. Like the literary and cultural academies founded around the same time, the Academy of Sciences enjoyed royal protection and some support from the Royal Treasury, while also preserving enough autonomy to place it out of reach of national politics—an important advantage, analogous to what we understand as “academic freedom” today. In a eulogy of Colbert he drafted in 1771, Lavoisier described the academies as “little republics,” noting that “their active power also overwhelms any opposition arising from ignorance, superstition, and barbarism.”

In 1764 Lavoisier began work on a project for street lighting in Paris for a competition sponsored by the Academy. Ever willing to use himself as a scientific subject, Lavoisier sequestered himself in a blacked-out room for six weeks to carry out his study. Deemed more theoretical than practical, his essay was nevertheless accepted for publication by the Academy, and a gold medal was struck to honor his achievement. In 1765, in the role of “visiting scientist,” Lavoisier presented a paper to the Academy titled “The Analysis of Gypsum” (the essential ingredient of plaster of Paris); the Academy reviewers praised his work for the “ingenious explication by which it reduces the phenomenon of the hardening of plaster to the simple laws of crystalization.”

Apolitical as the Academy was meant to be, election (as the word implies) was not without a political dimension. The apprenticeships Lavoisier had served with Academicians like Guettard and Jussieu gave him a solid base of support; other backers were friends of his father. The Academy had a fixed number of members, and vacancies at the lower levels were typically created by promotion to the higher ranks. Despite recognition of his promise and a considerable lobbying effort, Lavoisier was not nominated for the vacancy that occurred in the chemistry section in 1766, and for which he competed against much older scientists with longer-established careers.

Following this setback, Lavoisier returned to a project creating a mineralogical atlas of France that he and Guettard had begun earlier, and spent most of the next two years doing fieldwork outside of Paris. Meanwhile his father, who had apparently accepted Lavoisier’s determination to make the sciences the center of his working life, continued to manipulate whatever Academic threads passed through his hands, maintaining a climate of receptivity for his son’s efforts. In the spring of 1768, Lavoisier returned to Paris with new papers to present, one on “techniques for determining the specific weights of liquids” and another on “the character of the waters” in regions he had visited for the mineralogical survey. The pairing offered a nice balance of pure science with a practical application to the issue of the national water supply.

In May of 1768 Lavoisier and Gabriel Jars were nominated for a vacancy that had opened in March of that year. Because of his longer years of service, Jars was named to the vacant post, but Lavoisier was also offered immediate membership in the chemistry section as a “supernumerary adjunct,” on the understanding that he would be confirmed in the next vacancy that occurred. In fact, Lavoisier had received a few more votes than Jars; the solution was arbitrated by the king. To the Academicians who might have looked askance at Lavoisier’s involvement in the socially dubious General Farm, a Monsieur Fontaine retorted, “That’s just fine! The dinners he will serve us will be all the better!”

THE AVERAGE ANNUAL stipend for a member of the Academy of Sciences was two thousand livres, not to be sneezed at but also well short of what it took to sustain a middle-class manner of living in Paris—and as a new member, Lavoisier could not have expected to earn so much from his Academy post right away. With money bequeathed to him by his mother, he bought his first shares in the General Farm a matter of weeks before his election to the Academy of Sciences. This step freed him from any need to support himself by the practice of law. In theory, at least, Lavoisier could live (more than comfortably) on investment income while dedicating his working hours to science; in fact, his involvement with the General Farm became the occasion for a considerable amount of public service work, often overlapping with his scientific interests and research.

He began as a regional inspector for the Farm’s Tobacco Commission, combining his inspections with his exploratory trips for the mineralogical atlas in 1769 and 1770. Lavoisier’s mission was to fight a vigorous trade in contraband tobacco, mixed by retailers with tobacco properly taxed by the Farm. He reported his results to Jacques Paulze, a senior partner in the Farm who was also, like Lavoisier’s father, a lawyer in Parlement de Paris.

In 1770, soon after the death of his wife, Paulze brought his daughter back from the Montbrison convent, where she had been educated, to his Parisian domicile. Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze, thirteen years old, was meant to serve her father as hostess. Antoine Lavoisier, then twenty-seven, was thrown into her company. Marie-Anne was her father’s only daughter, as Lavoisier was an only son, and like Lavoisier, she had lost her mother at an early age. Despite her youth, she played her domestic role with confidence and grace, and she was attractive, with “very blue eyes, brown hair, fresh coloring and a small mouth.”

Eighteenth-century bourgeois marriages were business deals first and romances later—if at all. Marie-Anne Paulze, who was a significant heiress among her other advantages, became the target of a hostile takeover attempt. The suitor was the comte d’Amerval, an impoverished fifty-year-old nobleman with a name for dissipation. Marie-Anne herself described him as “a fool, an unfeeling rustic and an ogre.” In a letter to his wife’s uncle, the abbé de Terray, Jacques Paulze toned down Marie’s reaction to “a decided aversion,” and said, quite firmly, that he would not force her into a marriage she disliked. Attracted by Amerval’s title and under the influence of Amerval’s sister, the baroness de La Garde, Terray continued to press for the match. As controller-general of finances, Terray had the power to remove Paulze from the directorship of the General Farms department of tobacco, and threatened to do so. With the aid of other allies, Paulze protected his job, but he saw that his daughter would remain vulnerable so long as she remained unmarried.

In age, temperament, and financial position, Antoine Lavoisier was a much more appealing match for Marie-Anne than Amerval, and not at all displeasing to the girl. The two were married on December 16, 1771—the bride fourteen, the groom exactly twice her age. Gracious in his disappointment, Terray attended the ceremony as a witness for the bride, who had spent barely a year at home between the time she left the convent and her marriage.

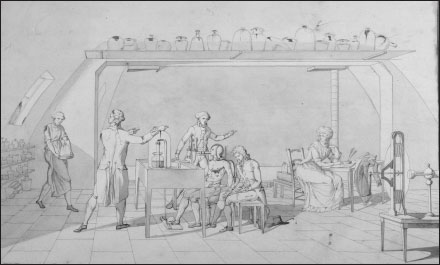

Madame Marie-Anne Lavoisier grew to be a person of substantial talent and accomplishment. She seems to have shared, at least to some extent, Lavoisier’s retiring disposition and his preference for productive work. Although she began a long-term affair with one of her husband’s colleagues, Pierre-Samuel Dupont, in 1781 (after thirteen years of marriage), she conducted it with such discretion that no one seems to have suspected it until after her husband’s death. And her devotion to Lavoisier’s career was unfaltering. Childless, she served Lavoisier as a very efficient laboratory assistant, if not a manager. Lavoisier gave her her first lessons in chemistry, and later on she studied the subject with Jean-Baptiste Bucquet. She kept meticulous notes on experiments and helped draft numerous of Lavoisier’s texts. Her knowledge of Latin and English enabled her to translate articles and, when necessary, entire books. Many illustrations of Lavoisier’s equipment and materials came from her hand; her nicely composed sketches of his respiration experiments include her as a working member of the team.

Marie-Anne’s considerable talent for drawing led her to become a pupil of the icon of French neoclassical painting, Jacques-Louis David. Apart from the scientific illustrations, little of her artwork has survived, other than a portrait of Benjamin Franklin which she presented to him as a gift in 1788. Though she appears not to have cared much for society for its own sake, during the twenty-three years of their marriage, she made the Lavoisier household one of the most important scientific salons in Paris. Her role in Lavoisier’s life was memorialized in a poem by Jean-François Ducis:

Drawing by Madame Lavoisier of one of Lavoisier’s experiments on respiration, involving a subject performing an activity. Madame Lavoisier is on the right, making notes.

Épouse et cousine à la fois,

Sûre d’aimer et de plaire,

Pour Lavoisier, soumis à vos lois,

Vous remplissez les deux emplois,

Et de muse et de secrétaire.*

FROM EARLY DAYS Lavoisier had a strong interest in applications of science to the public good. His study of Parisian street lighting was followed in 1768 by an analysis, on behalf of the Academy of Sciences, of a proposal by Antoine de Parcieux for an aqueduct to bring water into Paris from the river Yvette—relieving citizens of dependence on the polluted waters of the Seine. Due to lack of funds, and to Parcieux’s death, the aqueduct was never built, but the analysis of water quality gave Lavoisier his first concentrated look at the composition of water and bolstered his interest in sanitation issues. When the aqueduct project failed, he began to investigate methods for purifying the water of the Seine. He understood that clean air was as important to health as clean water, and ventilation was key to his study for a reconstruction of the Hôtel-Dieu hospital, burned in 1772, and a study for a hygienic reform of Parisian prisons he directed in 1780.

As Lavoisier was the enemy of disorder and dirt in matters of public health, so too was he the enemy of chaos and disorganization in matters of administration. His temperament led him to discover principles of order wherever they existed, and to impose them where they did not. As tobacco inspector for the General Farm, Lavoisier developed a chemical test for adulteration: ash mingled with tobacco would reveal itself by an effervescent reaction to acid solutions such as spirit of vitriol. He disliked the contamination of tobacco with ash not only as a form of tax fraud but also as a hazard to the public health, and at the same time he was sensitive to the severity of the punishments for such offenses. Adulteration detected at the point of sale might have taken place somewhere else along the supply line; to isolate it, Lavoisier imposed a meticulous system of weighing and accounting at every stage of tobacco’s journey to the retail market. This method for determining exactly when and how a change took place was much the same in its principle as the method he was learning to use in chemistry.

His work for the General Farm gave Lavoisier a vested interest in precise accounting, an interest that carried over into abstract economics. Heavily invested as he was in the existing tax system, he was not blind to its flaws or to the way in which those flaws impeded growth of the French economy. In the eulogy of the finance minister Colbert that he began in 1771 for another Academy competition, Lavoisier seems to admire his subject most for an ability to bring order out of anarchy: “In the midst of the chaos that surrounded him, and sustained by his own courage and the profound truth of his perceptions, he conjoined the law to the good.” That conjunction could serve as a definition of rational idealism, and probably did define Lavoisier’s sense of his own mission as a social reformer in several spheres, including economics and finance. Rational idealism implies its own morals, and the sum of Lavoisier’s actions seems to prove that in fact “la droiture du coeur”* was fully as important as “la justesse de l’ésprit”† in the quest for truth.

In his examination of Colbert, Lavoisier began to understand money as “a fluid whose movements necessarily result in equilibrium,” borrowing this analogy from physics. The exact balancing of precisely measured quantities by which Lavoisier learned to illuminate the affairs of the General Farm, and later used in the larger financial affairs of the French state, applied just as well to his work in chemistry. In the words of Charles Gillispie, a biographer, “to finance, munitions, and science alike he brought the luminous accuracy of mind that was his signet, the spirit of accountancy raised to genius.”

IN 1774 ANNE-ROBERT-JACQUES TURGOT replaced the abbé de Terray as controller-general of finance. Lavoisier was assigned by the Company of General Farmers to prepare a report on the Farm that Turgot had requested. Turgot was influenced by the French economic school called the Physiocrats to regard economics as an exact science, with laws as definite and permanent as those recently declared by Newtonian physics. Economic policy could thus be understood as a scientific application. These views were thoroughly congenial to Lavoisier, whose purely scientific ambition was to furnish chemistry with the clear definition physics had attained not long before. He cooperated enthusiastically with Turgot’s initiatives, though many other General Farmers felt threatened by them. In fact, the hectic pace of Turgot’s reforms menaced so many established interests that Turgot was dismissed in 1776, after a mere twenty months as controller-general.

The Swiss-born banker Jacques Necker, whose essay on Colbert had won the Academy competition from which Lavoisier had withdrawn, succeeded Turgot. Necker’s reputation as a ruthlessly cutthroat financier was not undeserved, but he seemed the man for an hour when “a Controller-General is expected principally to find money and do nothing more.” And after Turgot’s thrilling, brief tenure, conservatives must have been reassured by Necker’s declaration that reforms should be undertaken “without too grand an ardor.”

One of Turgot’s last acts as controller-general was the creation of the Caisse d’Escompte, or Discount Bank—a private institution, but with the important function of lending money to the Royal Treasury. In 1788 Lavoisier became a director of the Discount Bank. By 1789, as the first phase of the French Revolution unfolded, national finances were in crisis, and the private stockholders of the Discount Bank grew unwilling to lend more money to a government whose debt to the bank was already heavy. Jacques Necker responded with a proposal to nationalize the bank. Lavoisier, by then president of the bank’s board of directors, supported the plan, but it failed in the National Assembly. Indeed, because of the Discount Bank’s tenacity in protecting the stake of its private investors, it came under vigorous attack from the increasingly radicalized Assembly, with a faction led by Mirabeau demanding its liquidation.

By then the Discount Bank was in such a shaky situation that it could no longer redeem its own banknotes for cash, but Lavoisier and his fellow directors argued that the bank had been forced into this predicament by the government’s failure to repay loans, and that without the bank’s support, the Royal Treasury would have collapsed and the whole French economy with it. It was a period of French food shortages verging on famine, requiring importation of wheat from abroad to make bread—the era of Marie-Antoinette’s famously unfortunate remark that if there was no bread for the poor, “Let them eat cake.” The real cake-eaters were just beginning to suspect the hazards the time held for them; the French state’s desperation for money would soon become a dire threat to private wealth and the people who owned it.

In the event, the notion of nationalizing the Discount Bank was superseded by a proposal by Mirabeau: that the state begin to issue its own paper money. These notes, called assignats, were supposed to be secured by lands that were seized from the church as the first wave of the Revolution rolled over France in the summer of 1789. Though Lavoisier disapproved of Mirabeau’s plan, he joined a committee to supervise the assignats, devoting most of his attention to the prevention of counterfeiting, with which the Discount Bank had also been plagued.

Though the General Farm had not yet been formally abolished, the taxes it collected had been repealed by then, and the rest of the tax system was in similar disarray. Licensing an impoverished government to print its own money had the predictable result. Repayment of its loans in assignats further undermined the paper issued by the Discount Bank. As both assignats and banknotes lost value, and the price of bread climbed absurdly high, public opinion turned further against the fiscal conservatives, Lavoisier among them, who had tried to stop the inflationary spiral from beginning in the first place. The National Assembly resolved to reclaim public finances from the hands of “the great corps of venal financiers.”

In September of 1790, as the atmosphere darkened, Jacques Necker precipitously left France. As Marat’s diatribe underlined, the collegial relationship Necker and Lavoisier had enjoyed now became a dangerous association to the man who stayed behind. Though Lavoisier’s conduct in finance had been impeccable, the fact that he simultaneously held positions in the Discount Bank and the Royal Treasury, to which he had been appointed in April 1790, suddenly looked suspicious. Lavoisier decided to decline his salary from the Treasury, and on April 9, 1791, he made the dubious move of announcing his decision in an open letter to Le Moniteur. “The emoluments I enjoy as Administrator of Gunpowder,” he wrote, “precisely because they are moderate, agree with my manner of living, my tastes and my needs, and at a moment when so many honest citizens are losing their security, I could not for anything in the world consent to profit from a double salary.” This program of retrenchment was probably sound, but announcing it publicly was a misstep that only brought more hostile attention to the point that while Lavoisier’s manner of living could fairly be described as “moderate,” the extent of his wealth and resources could not.

LIKE HIS INVOLVEMENT in French public finances, Lavoisier’s interest in the making of gunpowder originated in the overlap of his work for the General Farm with Turgot’s short-lived ministry. In the 1770s the Farm charged him with inspections not only for the tobacco tax but also for the salt tax, and since saltpeter refiners liked to evade taxes on the sale of the salt, which was a by-product of their process, Lavoisier got involved. The royal prerogative to collect saltpeter, though not part of the General Farm’s authority, had traditionally been leased out to private interests on a similarly antique and cumbersome basis. The French state had a right to search for saltpeter anywhere, and saltpeter collectors’ license to invade private property (even to scrape saltpeter from the interior walls of private houses) was fraught with abuse.

Of course there was a national interest in the supply and quality of French gunpowder, which, before Lavoisier and Turgot turned to the matter, had become notoriously unreliable. Indeed, France had been obliged to bring the Seven Years’ War to a hasty conclusion, on unfavorable terms, because, thanks to a saltpeter shortage, the gunpowder supply had run out. As an inspector for the salt tax, Lavoisier discovered the manifold inefficiencies of the method of gunpowder production then in use and reported them to Turgot, who rescinded the lease of the Gunpowder Farm and authorized Lavoisier, Henri François d’Ormesson, and Pierre-Samuel Dupont to create a new Régie des Poudres et Salpêtres (Gunpowder and Saltpeter Administration).

Lavoisier, who wielded executive authority for the new Gunpowder Administration, immediately suppressed the search and seizure rights of the saltpeter collectors. In 1775, with Turgot’s support, he organized an Academy of Sciences competition for studies on both the natural formation and the artificial production of saltpeter. His mineralogical travels with Guettard gave Lavoisier some background in the former; concerning the latter, it was convenient that one of France’s very few cultivations of artificial saltpeter was on the outskirts of his family’s old hometown of Villers-Cotterêts.

Under Lavoisier’s direction, gunpowder research became a military science project with strong government backing. His series of programs worked toward better methods of extracting natural saltpeter, more efficient techniques for producing artificial saltpeter, and a more precise understanding of the chemistry of good gunpowder. These programs were so successful that by 1776 France had surpluses of gunpowder to offer to the American revolutionaries. In 1789 Lavoisier could claim, with some justice, that “North America owes its independence to French gunpowder.”

The closest gunpowder factory to Paris was nearby at Essonne; there the new research and development programs were put to the test. The work was not without its hazards. In 1788 the chemist Claude-Louis Berthollet discovered that a more powerful gunpowder could be made using a volatile muriate of potash. Lavoisier took a group of visitors on a tour of the Essonne powderworks on a day when the new formula was being tried. Though he had instructed his party to remain behind a safety barrier, not all of them obeyed, and when the mixture exploded, one of the chemists and a woman visitor were killed. Work at Essonne continued nonetheless; Éleuthère Irénée Dupont (son of Pierre-Samuel) got his first training on gunpowder-making there, and later on founded the Dupont chemical dynasty in the United States with a powder mill in Delaware.

When Turgot lost his office in 1776, all his reforms were threatened. Lavoisier maneuvered hard, and successfully, to protect the Gunpowder Administration as a government monopoly. The national need for a reliable supply of quality gunpowder was so great that it was best administered by a centralized authority. Lavoisier argued in another unpublished essay that though “every exclusive privilege is without question a violation of the natural order,” it was justified in this case by the urgency of the need and the success of the result.

It was not only the public good that attached Lavoisier to the Gunpowder Administration, which soon after its creation erected a new building on the grounds of the Paris Arsenal on the right bank of the Seine: the Hôtel des Poudres et Salpêtres. There Lavoisier built himself a state-of-the-art laboratory, which would be the theater of all his research and experimentation for the rest of his working life. For that reason, the Gunpowder Administration became the one of his several public posts he was most determined to retain when the tide turned against him in 1791. But in 1776 this position was more easily defended and, in fact, became quite a comfortable one for both Lavoisier and his wife, who moved to a private apartment in the Petit Arsenal in April of that year.

This situation meant that for all practical purposes Lavoisier woke up in his laboratory every day. His daily routine was as orderly as the mind of the man. Rising at 5:00 A.M., he devoted three morning hours to pure science in the lab, then spent the hours from 9:00 A.M. to 7:00 P.M. on affairs of the General Farm, the Gunpowder Administration, and the Academy of Sciences, housed at that time in a capacious suite of rooms in the Louvre. Another three evening hours were devoted to scientific work in the Arsenal laboratory. In addition, Lavoisier spent all of his Saturdays there, with a growing coterie of students. Marie-Anne Lavoisier, who though not yet twenty was vigorously acquiring the broad set of skills that would make her indispensable to her husband’s research programs, wrote of Lavoisier’s scientific Saturdays, “It was for him a day of happiness; a few enlightened friends, a few young people proud to be admitted to the honor of participating in his experiments, gathered in the laboratory in the early morning; it was there that we lunched, there that we held forth, there that we created that theory which has immortalized its author.”

These were productive and happy years for Lavoisier and his wife. Lavoisier’s adolescent shyness seems to have diminished as he settled into his marriage and began to become a quite prominent public figure. The couple went out frequently to the Paris Opéra and, because of Marie-Anne’s interest in painting (she had recently begun her lessons with David), to art exhibitions. Madame Lavoisier’s skills as secretary, lab assistant, promoter, and publicist were matched by her social graces, and the Lavoisier salon at the Arsenal was frequented by the most illustrious members of the international scientific community: Joseph Priestley, Joseph Black, Martinus Van Marum, Horace de Saussure, and Benjamin Franklin, who was the toast of Paris in the years following the success of the American Revolution, and whom the Lavoisiers especially courted.

The Arsenal laboratory remained at the center of Lavoisier’s life even after he removed his private domicile to boulevard de la Madeleine. He also remained one of those responsible for the large powder depot there. Some of the Arsenal buildings actually communicated with the adjacent fortress of the Bastille; powder for the Bastille was stored in the Petit Arsenal near the Lavoisier apartment (a circumstance that may have inspired Lavoisier to design new magazines that would discharge their contents harmlessly through the roof in case of accidental explosion). On the twelfth and thirteenth of July in 1789, the commander of the Bastille became concerned that the Arsenal magazines might be blown up or their contents stolen by revolutionary rioters, and ordered that the Arsenal powder be transferred to the fortress. Though Lavoisier and his fellow directors had no choice but to comply, their obedience brought them under suspicion as “enemies of the people” who had schemed to deprive the Paris populace of the powder they needed to overthrow the monarchy.

The Bastille fell on July 14, and by August, mob rule had a footing in Paris. At the first of the month, the Arsenal magazines were clogged with inferior powder being transshipped to Rouen and Nantes for sale to slavers. Lavoisier was supervising the loading of a barge with powder cases marked “poudre de traîte.” The word traîte, which means “trade,” had become the commonly used term for the slave trade. This innocuous label was interpreted by the large, excited, half-literate crowd that gathered to mean “traitor’s powder.” A cry went round that the barge was charged with munitions to put down the Paris Revolution. Hysteria erupted and Lavoisier, with another Gunpowder director, Jean-Pierre Le Facheux, found himself captive of the mob. The frustration of this eminently rational man as he tried to explain the idiotic misreading of the “trade powder” label to his captors can only be imagined.

During the July gunpowder crisis, Lavoisier and his colleagues had held out a week’s supply of powder for the National Guard, which now appeared to protect them from being hung from lampposts en route to the Hôtel de Ville. The crowd poured into the hall for a public debate in which Lavoiser finally managed to convince his audience of the harmlessness of his own actions. The crowd’s ire then shifted to the marquis de La Salle, the National Guard commander who had signed the order for the gunpowder shipment, and in this fresh burst of confusion, Lavoisier managed to slip safely away.

It was a narrow escape, and a lucky one; summary mob executions had become frighteningly common in the summer of 1789. Lavoisier and his friends were discouraged from publishing a justification of their conduct, and such a shadow of suspicion lay over these wholly innocent events that the mere mention of the Gunpowder Administration in Marat’s anti-Lavoisier diatribe had an opprobrious tinge.

AS A RISING administrative star in the General Farm, Lavoisier was concerned not only with the taxes on salt and tobacco but also with the duties on goods entering Paris from outside the city. Paris had long since sprawled beyond its old barriers, and the absence of a clear system of checkpoints was complemented by a bewildering disarray of collection and inspection practices involving twelve hundred confused employees: another chaos for Lavoisier to organize. Lavoisier had proposed the construction of a new wall around Paris as early as 1779, but the idea lay dormant until 1783, when he was appointed to the General Farm’s central administrative committee, which had direct responsibility for tax collection at the Paris tollgates. The central committee supposed that 20 percent of goods coming into Paris slipped silently through tears in the tax net, for a loss of 6 million livres a year.

In 1787 the highly regarded architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux was commissioned to design and build the Farmers’ tax enclosure—an elaborate and very expensive project featuring a heavy stone wall six feet high, punctuated by sixty-six elegant Palladian pavilions serving as tollgates—each with a different design. Though fifty-eight of Ledoux’s gates were completed, only four survive today: in the Parc Monceau, at the Place de la Nation, at the southern terminus of the bassin de la Villette, and above the catacombs in the Place Denfert-Rochereau.

The wall was horrendously expensive—at 30 million livres, it cost five times the annual revenue loss it was intended to prevent—and despite its architectural grandeur, it was vastly unpopular. Louis-Sébastien Mercier adapted the public sentiment into a sardonic quatrain:

Pour augmenter son numéraire

Et raccourcir notre horizon

La ferme a jugé nécessaire

De nous mettre tous en prison.*

An anonymous pamphlet suggested that while the General Farm might want to raise a statue to Lavoisier on the ramparts of its wall, the Academy of Sciences should blush for the association. The same pamphleteer claimed that the duc de Nivernois, a marshal of France, said when asked what he thought of the new wall, “I am of the opinion that its author should be hanged.” A multilayered pun of unknown authorship began to run through the Paris salons: “Le mur murant Paris rend Paris murmurant.”†

By the summer of 1789, Paris was muttering and grumbling over more than just the tax wall, which remained, however, an obvious and convenient target. The Farmers’ wall was just short of completion on July 13, when (in the midst of the first gunpowder crisis at the Arsenal, and scarcely twenty-four hours before the sack of the Bastille) the Paris mobs began tearing it down, setting fire to most of Ledoux’s lovely tollgates in the process. Two years later, the wall controversy helped fuel another attack on Lavoisier from Marat in his pamphlet Modern Charlatans: “If you ask what he has done to be so much extolled, I shall reply that he has procured himself an income of a hundred thousand livres, that he has contributed the project to make Paris a vast prison, and that he has changed the term acid into oxygen, the term phlogiston into nitrogen, the term marine into muriatic, and the term nitrous into nitric and nitrac. Behold his titles to immortality. Proud of his lofty deeds, he now sleeps on his laurels.”

MARAT’S ANIMOSITY TO Lavoisier dates back to 1779, when the firebrand journalist and provocateur (as history would finally remember him) made a serious effort to win the respect and celebrity in the sciences that Lavoisier had already begun to enjoy. In April of 1779, Marat demonstrated to Benjamin Franklin and the Academicians Balthazar Georges Sage, Jean-Baptiste LeRoy, and Trudaine de Montigny a series of optical experiments that purported to make visible the “matter of fire” or “igneous fluid.” He had concocted a theory to explain the phenomena he displayed: “that fire resulted from the activation of particles of the igneous fluid contained in the bodies.” The Academic observers praised the ingenuity of the experiments but declined to comment on the theory.

Marat continued to press for Academy recommendation of his theories about light, color, and fire. But when Lavoisier was appointed to a new academy team of observers, Marat objected to his presence. Lavoisier had himself begun a much more rigorous program of experiments in combustion in 1772, and Marat might have been right to anticipate that Lavoisier would not be impressed by his ideas and demonstrations. And in any case the demonstration that Lavoisier would have observed was postponed for lack of sun. Pressed by Marat for an endorsement of his experiments, the Academy of Sciences finally answered, on May 10: “It would be useless to go into detail to make them known; the commissioners do not regard them to be of a nature such that the Academy could give them its approbation or support.”

One month later, an article in the Journal de Paris reported Marat’s experiments and theories on the “matter of fire” as if the Academy had approved them. It was Lavoisier who noticed the false assertion and prompted a public repudiation. Definitively rebuffed by the Academy of Sciences, Marat developed a vivid hostility to the scientific establishment in general and Lavoisier in particular, and he took whatever opportunity he could find to attack both.

IN FACT, MARAT’S fantasies about light, color, and “igneous fluid” were not far out of line with other pseudoscientific postulations of the day. Part of the mission of the Academy of Sciences—a project in which Lavoisier took special interest—was to arbitrate what was scientifically legitimate and what was not. Meanwhile, the whole definition of scientific orthodoxy was undergoing changes that Lavoisier himself described as revolutionary.

One of Lavoisier’s first assignments for the Academy was an investigation of the divining rod—the tool of a persistent folk technique by which underground water is supposed to be detected by movements of a forked stick held by the diviner. Lavoisier’s debunking of the practice was reasonably tactful: “There is water almost everywhere, and it is rare that one digs a well without finding some. So there is nothing out of the ordinary in the facts which are reported and to which one is tempted to attach a great importance; as this rod sometimes turns by involuntary movements on the part of the person who holds it, it is possible that some persons of good faith have been deceived and have attributed to an external cause an effect which depends only upon themselves.”

Fifteen years later, in 1784, Lavoisier served on a committee that included among other scientific eminences Benjamin Franklin and the soon-to-be-notorious Dr. Guillotin, and that was charged with the investigation of “animal magnetism,” a healing method made extremely fashionable in France by its leading practitioner, Anton Mesmer. In later years, “mesmerism” became synonymous with hypnotism, and it is worth noting that in our own time the effects of hypnotism, while understood to be psychological rather than physical, are accepted as being quite authentic and are used in therapies not greatly dissimilar to those Mesmer practiced in the eighteenth century. But if Mesmer knew he was practicing hypnotism, he did not say so. He claimed, and most likely believed, that his effects were produced by the manipulation of an invisible energy, like electricity, on which Franklin had done celebrated work, or the matter of fire, which turned out not to exist any more than Mesmer’s animal magnetism did.

Mesmer’s method of induction, which had been disseminated across an extensive network of practitioners by the time the Academy of Sciences took an interest, resembled a spiritualistic seance. Participants sat around a low tub full of damp sand, bottles of water, iron filings, rods, and other magnetic material. So as to be “magnetized,” they grasped each other’s thumbs and were also connected to each other and the iron rods by a cable. Soft music played while the mesmerist used flowing passes of his hands to manipulate the magnetic fluid that was supposed to suffuse this environment. Since most people have some susceptibility to hypnotism, most subjects of these procedures would have been likely to experience some level of hypnotic trance.

Lavoisier brought to bear on mesmerism the meticulous method of evidence sifting he used everywhere else. Certain effects of mesmerism, like the coincidental presence of water beneath the witch’s wand, could not be denied (convulsive seizures could be reliably produced in the more susceptible subjects and were offered as evidence of “magnetism”). What stood to be challenged were the mesmerists’ claims about causes. Through process of elimination, Lavoisier established that the same effects could be produced just as reliably without any magnets, simply through suggestion and touch; “imagination in the absence of magnetism produces all the effects attributed to magnetism,” Lavoisier wrote; “magnetism without imagination produces no effects.”

The committee reported that mesmerism was bunk, and on that basis the government launched a largely successful campaign to extirpate what amounted to a French mesmeric cult. Believers in mesmerism were hard to dissuade—the comparison to hypnotism suggests that mesmerism did produce real therapeutic results for many, though its explanations were spurious. The believers were numerous and some of them were powerful and would become more so during the revolutionary years. They included Jean-Paul Marat and his friend Jacques-Pierre Brissot, who like Marat had been frustrated in his efforts to penetrate the recently redefined scientific community and had turned to increasingly incendiary journalism. Brissot, who would occupy an extremely influential role in the Jacobin government before the Terror, began to target the Academy of Sciences (which did after all derive its authority from the throne) as a tyrannical institution. “The empire of the sciences must know no despots, no aristocrats, no electors,” he wrote. “To admit a despot, or aristocrats, or electors officially empowered to set the seal on the production of genius, is to violate the nature of things and the liberty of the human mind.”

It is more likely than not that Lavoisier approached mesmerism without preconceptions. He had trained himself to be resistant to received ideas. The invisible energy of electricity had recently been proved as an authentic physical phenomenon, and Lavoisier’s own most crucial research program revolved around the investigation of the matter of fire. He took the investigation of mesmerism quite seriously, and a paper he wrote on the subject contains one of the most articulate statements he ever made about his own views of scientific rigor:

The art of drawing conclusions from experiments and observations consists in evaluating probabilities and estimating if they are large and numerous enough to constitute proofs. This type of calculation is more complicated and more difficult than we think; it demands a great sagacity, and it is in general beyond the powers of ordinary men.

It’s on their errors in this sort of calculation that the success of charlatans, sorcerors, and alchemists is founded; likewise, in other times, that of magicians, enchanters, and in general all those who have deluded themselves or who seek to abuse public credulity.

There is more than a touch of aristocratic hauteur to be read between these lines, but perhaps Lavoisier himself did not notice it.