II

Out of Alchemy

Lavoisier first flirted with chemistry in his teens at the Collège Mazarin, where Louis de La Planche taught a three-tier course in the subject. The first year was devoted to “the dictionary of the science,” the second to an initial unfolding of ideas behind it, and the third to acquisition of “true knowledge.” As a student, Lavoisier found the program poorly organized. Later he wrote, “I was surprised to see how much obscurity surrounded the approaches to the science. During the first steps, they began by supposing in place of proving. They presented me with words which they were in absolutely no condition to define for me, or which at least they could not define without borrowing from knowledge that was absolutely foreign to me, and which I could only acquire by the study of the whole of chemistry. And so, in beginning to teach me the science, they supposed that I already knew it.”

Here was just the sort of confusion that the mature Lavoisier loved to sort out and reorganize. And at the same time that he was enduring this lengthy but bewildering instruction in chemistry, he was also working in a much more clearly methodical fashion with the astronomer and mathematician Lacaille, in charge of mathematics and “exact sciences” (to which chemistry did not then belong) for the Collège Mazarin. Under Lacaille’s tutelage, Lavoisier became, as he put it, “accustomed to the rigor of reasoning which mathematicians put into their work; never do they accept a proposition when the one which precedes it has not been discovered. Everything is connected, everything is linked, from the definition of the point, of the line, all the way to the most sublime truths of transcendant geometry.” And Lacaille put as much emphasis on clear expression and precise terminology as he did on rigorous reasoning, exchanging the Latin that had been the traditional language of savants in any field for the French of his contemporaries—the Encyclopédistes, the Lumières, the scholars of the Enlightenment who were bringing their tongue to a point of refinement where it would replace Latin as the international language for any and all subjects.

After finishing his studies at the Collège Mazarin, Lavoisier took a series of chemistry courses at the Jardin du Roi from the famous Guillaume-François Rouelle—courses attended by many other emerging scientists of the French Enlightenment. Rouelle’s chemistry was up-to-date, which in the 1760s meant that it was largely based on the theories of the German protochemist Georg Ernst Stahl. Rouelle had a relatively pragmatic, hands-on attitude to chemistry, which he defined as “an art which teaches us to separate by means of instruments, several bodies; to combine them to the end to be reacquainted with their properties and render them useful to the several arts.” Techniques of analysis and synthesis were included in Rouelle’s experimental practice, which as a gifted performer he knew how to dramatize for his audience of students, sometimes with an inadvertent explosion. Though progressive in the sense that he moved the study of chemistry in the direction of quantification, Rouelle also retained some aspects of alchemical philosophy, which he sought to combine with an emerging theory of empirically defined elements. The impossibility of this combination undoubtedly produced some confusion in his teaching.

“The celebrated professor,” Lavoisier wrote of Rouelle, “joined much method in his manner of presenting his ideas to much obscurity in his manner of articulating them.” This statement, surely as contradictory and confusing as whatever it meant to complain about, suggests that the student was simultaneously impressed and dissatisfied with the teacher and the course. Lavoisier’s objection grew clearer as he went on: “I managed to gain a clear and precise idea of the state that chemistry had arrived at by that time. Yet it was nonetheless true that I had spent four years studying a science that was founded on only a few facts, that this science was composed of absolutely incoherent ideas and unproven suppositions, that it had no method of instruction, and that it was untouched by the logic of science. It was at this point that I realized I would have to begin the study of chemistry all over again.” Here indeed was a radical statement; Lavoisier was willing to tear the rickety structure of chemistry right down to the ground and begin to rebuild it from point zero.

THE OBSCURITY OF chemistry as Lavoisier found it in the mid-eighteenth century owed much to its passage through medieval and Renaissance alchemy. Taken as a lump, alchemy is so far from the modern standard of exact science that twentieth-century writers like Joseph Campbell, Northrop Frye, and most notably the psychoanalytic philosopher Carl Jung have tended to treat it not as an exact science at all, but as a philosophical/religious system clothed in pseudochemical allegory; Jung indeed admired the architecture of the alchemical edifice, but only as an elaborate metaphor for processes in the human psyche.

Alchemy was certainly suffused with magical thinking, and its loftiest goals, such as the transmutation of base metals into silver or gold, the discovery or synthesis of the “philosopher’s stone,” and the acquisition of human immortality, were fantastically impracticable, at least on the plane of physical reality. Though modern science has shown the transmutation of metals to be possible after all, it turns out not to be worth the trouble and expense. A century before Lavoisier’s time, one disillusioned alchemist denounced the project of transmuting metals as “a lunatic, melancholy fantasy.”

Believing that it owned extremely valuable secrets, alchemy protected them in modes of expression that were most intentionally obscure. A parable from Bernard Trevisan’s De secretissimo philosophorum opere chemico “begins with Bernard relaxing after a disputation by taking a walk in the open fields. He comes upon a beautifully constructed fountain and meets an old man there who tells him that the fountain’s only use is as a bath for the king and that it is tended by a porter who warms it for him. Bernard asks the old man many questions about the king and his odd bathing practices and about the nature of the fountain. Eventually Bernard grows sleepy and accidentally drops a golden book (the prize from his disputation) into the fountain, drains the fountain to retrieve the book, and is thrown into prison for draining the king’s fountain. After his release, Bernard returns to the fountain to find it covered in clouds.”

George Starkey, a seventeenth-century alchemist, is sufficiently initiated in such arcana to be able to interpret this dreamlike allegory as a chemical formula. As described by historians William R. Newman and Lawrence M. Principe,

First he [Starkey] notes that when the king, whom he easily identifies as gold, comes to bathe, he leaves “behind him all his servants (which are the metalls)” being accompanied only by a porter. Thus it seems here that iron, one of the lesser metals and thus one of the king’s servants, must be “left behind.”…This porter is surely the “Luna,” or necessary medium between gold and mercury (i.e., the king and his bath), which he has identified as antimony regulus. Now Starkey notes that Bernard affirms “this Porter…to be most simple of al things in the world whose office is nothing but day by day to warme the bath (that is by making al fluid) now if it were compounded it could not be sayd to be so simple, which is uncompounded.” Here Starkey interprets Bernard’s use of the word “simple,” which in the context of the parable means that the porter is unsophisticated or naive—“homo valde simplex, imo simplicissimus hominum”—to mean compositionally simple, that is, uncompounded, implying that pure “simple” antimony regulus should be jointed to the king/gold, not the regulus containing iron…. He next notes that Bernard asked the old man whether any of the king’s servants went into the bath with him and the “answer is returned not one, and if not one, then not iron.”

Lunatic fantasy, indeed. By Lavoisier’s day, several centuries’ worth of this sort of baroque obfuscation had intervened between the scientists of the Enlightenment and the propositions about elemental chemistry made by the ancient Greeks. Much of the alchemist’s time and effort went into the encoding and decoding of information that would prove scientifically dubious if ever it could be clearly understood. Carl Jung was not wrong in his contention that alchemy makes larger, more general sense if interpreted as a psychological/philosophical vision of humanity in the world than as an exact science, precisely descriptive and explanatory of material phenomena. Of course, this latter definition of science was just beginning to crystallize in Antoine Lavoisier’s time. During the lengthy age of alchemy, and even during classical antiquity, the word science meant knowledge as a whole—knowledge of religion and philosophy as well as knowledge of concrete facts about the material world. When physics and metaphysics are not distinguished or divorced from one another, then mystical insight may be as legitimate a means of acquiring knowledge as any other—legitimate as the sort of experiment and analysis that fits the narrower definition of science we use today.

Jung, in an essay on Paracelsus, noted that “the alchemist…worked alone…. This rigorous solitude, together with his preoccupation with the endless obscurities of the work, was sufficient to activate the unconscious and, through the power of imagination, to bring into being things that apparently were not before.” Though Jung does not mean it so pejoratively, this statement bears a certain resemblance to Lavoisier’s analysis of the role of imagination in mesmerism. Paracelsus himself put the point more plainly and more positively: “Magic has the power to experience and fathom things which are inherently inaccessible to human reason. For magic is a great secret wisdom, just as reason is a great public folly.”

A magically intuitive fathoming of order and organization in the universe is the basis of alchemy’s appeal as a mode of religious philosophy. It was unfortunate that alchemy’s most elegant philosophical and psychological insights kept falling short of the standards of material proof—but for centuries alchemists had a reflexive defense: “In alchemy, the laboratory has no crucial role. The function of the practice is first and foremost to illustrate the truth of the theory. The success of a procedure demonstrates to the operator that he has understood the ancients well. The quality of the practice is the direct consequence of the level of understanding of the theory. For if the experiment fails, the failure does not weaken the theory.”

In other words, alchemical theory was analogous to religious faith in its defiance of logic (when necessary) and in its imperviousness to inconvenient facts. And in this respect, the relationship of alchemical theory to alchemical practice was almost a perfect inversion of modern scientific method. For modern chemistry to be born, the alchemical world had to be turned upside down. In the seventeenth century, that world was already beginning to tilt.

Seventeenth-century alchemy was not all mystical hocus-pocus—permeated with magical thinking as it continued to be. Transitional figures such as Starkey and Robert Boyle continued to draw on alchemical lore, but subjected it to genuine experimental testing. Boyle, much influenced by the deductive methods of Francis Bacon, set forth in his treatise The Sceptical Chymist a much more empirical approach to chemistry than had previously been seen. Instead of disregarding experimental results when they were incompatible with a preexisting theory, Boyle and his ilk saw “failed” experiments as a challenge to existing theory—as doorways to new experimental programs and, accordingly, revision of theory. At the same time, he persisted in believing that transmutation of metals was practically possible and that the philosopher’s stone would one day be discovered. Because of the fundamental differences between the practice of Boyle, Starkey, and Jan Baptista van Helmont and that of both earlier alchemists and modern chemists, historians Newman and Principe distinguish the transitional seventeenth-century science as “chymistry.”

ALONGSIDE ALCHEMY EXISTED a parallel tradition related to the mining and refining of metals, codified in a manual of metallurgy by Georgius Agricola in the mid-sixteenth century. The metallurgical tradition was opposite to alchemy in its attitudes and intentions and so rather closer to those of modern science. Miners and refiners had a practical interest in creating a clear and accessible body of knowledge about their craft. Their practices were firmly based on results. Procedures needed to work reliably and be repeatable by anyone trained in them. Terminology had to be consistent and clear. The encryption of alchemical texts was irritating to Agricola, who wrote that “all are difficult to follow, because the writers upon these things use strange names, which do not properly belong to the metals, and because some of them employ now one name and now another, invented by themselves, though the thing itself change not.”

The metallurgical tradition produced a much more reliable lexicon of metals and minerals than alchemy ever wanted to do; Lavoisier himself relied on it when conducting his mineralogical expeditions with Guettard. And where alchemy was secretive and intentionally arcane, the techniques of mining and metallurgy were relatively open, since they had broad economic significance in the communities where they took place. But despite their very different attitudes, alchemy and metallurgy had a common interest in precious metals and used similar furnaces, crucibles, and distillation apparatus. Both traditions were engaged in the refinement and purification of elements by fire.

THE MODERN PERIODIC table identifies more than one hundred elements; its prototype, the Table of Chemical Nomenclature published by Lavoisier and his colleagues in 1787, lists fifty-five. Lavoisier’s table constituted a radical change in the whole notion of what an element was. Prior to his reorganization of the definitions and concepts, the Western scientific community had continued to labor over revisions of the elemental theory inherited from the ancient world.

The ancient elements were defined according to their direct accessibility to the senses—without any operations of analysis or chemical decomposition. The Chinese system identified five elements—metal, wood, fire, water, and earth—derived from the tension of opposites described in Taoism. Metal and fire were seen as yang elements—hot, bright, and masculine—while wood and water were yin elements—cool, dark, and feminine. The earth element stood on neutral ground, centered between the extremes of yin and yang. Compound substances were understood according to the proportions of the five elements they contained.

Chinese five-element theory was the basis for Chinese alchemy, which cross-pollinated with Western alchemy to some degree and which, like Western alchemy, had an interest in the transmutation of metals and the discovery of the secrets of immortality. Five-element theory also was and continues to be the basis for Chinese medicine, which evolved on a very different course from its Western counterpart. Chinese medicine still produces therapeutic results for patients all over the world, while for the most part remaining untouched by the logic of Western science.

Circa 450 B.C., the Greek philosopher Empedocles proposed four elements: fire, earth, air, and water. Aristotle supplemented the elements with four “qualities”: defining fire as hot and dry, water as cold and wet, air as hot and wet, and earth as cold and dry. As in Chinese five-element theory, compound substances were understood as mixtures of the four Aristotelian elements and the degrees of their attendant qualities. Nature conferred qualities to combinations of the elements to produce the metals mined from the earth. Western alchemy believed that this natural process could be artificially replicated, and so conceived the philosopher’s stone as the mechanism for the imposition of metallic qualities on “prime matter.”

During the Renaissance, Western alchemy intertwined itself with the tradition of Hermeticism and Hermetic beliefs in quasi-magical correspondences between the macrocosmos and the microcosmos, so that, for example, the macrocosmic organization of the universe could be mapped onto the microcosmic organization of the human body. Similarly, the metals were mapped to corresponding bodies of the ancient planetary system: lead to Saturn, copper to Venus, iron to Mars, silver to the moon, gold to the sun, and so on. Via this connection, the chemical vocabulary began to derive its terms from astrology, and the astrological idea of planetary influence took on an importance for alchemy.

Both Western and Chinese alchemy were interested in the creation of health along with wealth; alchemy contained a thread of nascent pharmacology up through seventeenth-century chymists such as Starkey and Boyle, who earned something from drugs and their formulae. Western medicine derived its fundamentals from the Greek Galen, who proposed four humors analogous to the Aristotelian four elements and defined states of health or illness according to the balance of humors in the body. Paracelsus, who directed his alchemy more toward medicine than metallurgy, rebelled against the Greek system of humors and elements and declared the existence of three primary principles—sulfur, mercury, and salt—which corresponded both to the Holy Trinity and to the components of the human being: “vital spirit, soul, and body.” According to Paracelsus, all alchemical transformation was controlled by the interaction of this tria prima.

As a doctor, Paracelsus had a useful strain of empiricism (he was, for example, the first to identify the causes of silicosis, a miners’ lung disease), but on the theoretical plane he remained a metaphysician and (by his own declaration) a magician. His rebellion did not succeed in dislodging Aristotelian science from orthodox European thought, but his ideas did have a pervasive influence throughout the seventeenth century. In what amounts to a prototypical vision of organic chemistry, Paracelsus saw life processes as a mode of alchemy; God, as Creator, is “the supreme alchemist.” Paracelsus and his followers objected to Aristotelian definitions (in sixteenth-century botanical nomenclature, for example) because of their descriptive and empirical character, which, in the Paracelsian view, failed to capture the universal correspondences on which authentic definitions must depend. “Within this vast and vital universe, the true physician had to reveal the hidden relations between microcosmos and macrocosmos, and interpret the signatures concealed by God in each single body.”

Before dismissing Paracelsus as a lunatic fantasist, it is instructive to compare him to a true physicist, Isaac Newton, who studied alchemy throughout his career, during the same decades that he explained gravitation and other fundamentals of physics. The laws of Newtonian physics (in the eyes of Newton, at least) were originally God-given. Like Paracelsus, like most alchemists in fact, Newton saw himself as a discoverer of divine properties installed by God in the natural world. His physics was thus subordinated to metaphysics, and his view of the universe as holistic as that of the philosophers, alchemists, and mystics. Lavoisier, though impressed by Newton and influenced by the logical rigor of Newtonian physics, would begin to deconstruct this holistic vision of the universe by concentrating much more narrowly on its component parts.

ROBERT BOYLE, A COUNTRYMAN and colleague of Isaac Newton’s, was not so successful in rationalizing chemistry as Newton was in rationalizing physics, though he did have an interest in doing so. In The Sceptical Chymist, he challenged both the Aristotelian and the Paracelsian conceptions of the elements. Seventeenth-century chymists had begun to suspect that the Aristotelian elements were mixtures, rather than pure substances. Van Helmont, another chymist whose work Boyle knew, contended that water contained both mercury and sulfur in its composition—two elements of Paracelsus’s tria prima.

But Boyle also undermined the tria prima via analysis by fire. Through various experiments he concluded “That the Fire even when it divides a Body into Substances of divers Consistences, does not most commonly analyze it into Hypostatical Principles, but only disposes its parts into new Textures, and thereby produces Concretes of a new indeed, but yet of a compound Nature.” Boyle invites his reader to consider, as a mode of analysis, “the Burning of Wood, which the Fire Dissipates into Smoake and Ashes: For not only the latter of these is Confessedly made up of two such Differing Bodies as Earth and Salt; but the former being condens’d into that Soot which adheres to our Chimneys, Discovers itself to Contain both Salt and Oyl, and Spirit and Earth, (and some portion of Phlegme too) which being, all almost, Equally Volatile to that Degree of Fire which Forces them up, (the more Volatile Parts Helping, perhaps, to carry up the more Fixt ones, as I have often Try’d in Dulcify’d Colcothar, Sublimed by Sal Armoniack Blended with it) are carried Up together, but may afterward be Separated by other Degrees of Fire, whose orderly Gradation allowes the Disparity of their Volatileness to Discover itself.”

In fewer words, the decomposition of wood by fire yields more compound substances, rather than pure, elementary ones. Meanwhile, Boyle recorded that pure gold would not decompose no matter how much it was heated, and that if he heated “a Mixture of Colliquated Silver and Gold…in the Fire alone, though vehement, the Metals remain unsevered,” though they could easily be separated “by Aqua Fortis, or Aqua Regis (according to the Predominancy of the Silver or the Gold).” Boyle’s distillation of blood yielded “phlegm, spirit, oil, salt, and earth”—five substances that were not certainly elementary. The chymical skeptic also distilled eels by boiling them and determined that “they seem’d to have been nothing but coagulated Phlegm, which does likewise strangely abound in Vipers.”

The very inconsistency of Boyle’s results—the product of his empirical skepticism—invalidated the existing elemental theories, since analysis by fire failed to decompose different substances into the same set of primary elements. Moreover, Boyle had begun to discern that “the Fire may sometimes as well alter Bodies as divide them, and by it we may obtain from a Mixt Body what was not Pre-existent in it”—that is, combustion could form new compounds with components not present in the substance being burned.

THE GERMAN PHYSICIAN and chemist Georg Stahl, whose career spanned the turn of the eighteenth century, built on a transformation of Paracelsian elemental theory by an earlier German experimenter, Johann Joachim Becher. In place of Paracelsus’s tria prima, Becher adopted air, earth, and water as the three elementary principles; for the moment fire, the fourth Aristotelian element, was removed from the picture. Becher further supposed that three different kinds of earth were required for the composition of metals and minerals, and that one of these earths, terra pinguis or “greasy dirt,” contained the principle of combustion. Van Helmont (a follower of Paracelsus and in some respects a leader of Becher) had earlier used the Greek phlogistos for inflammability; Becher employed the same term; Stahl adapted it to “phlogiston.”

Newton’s admirers hoped and expected that chemical questions would be mechanically resolved “in terms of the interaction of matter and forces,” as Newtonian physics resolved physical questions. Stahl disagreed, distinguishing (as Becher had done, but with greater refinement) between mixtures that he called “aggregates” and “mixts.” An aggregate was a mechanical mixture of substances accomplished by physical forces—like grains of sand shaken up in a jar. A mixt, by contrast, required a chemical reaction to produce it and therefore was a genuine chemical compound. Stahl defined chemistry as “the art of dissolving natural mixt bodies by various means”—that is, the analysis of compounds.

Fire, in Stahl’s chemistry, was not an element but an instrument; fire was not an ingredient to any mixt but rather the mechanical tool whose action assisted the mixt into being. Becher’s terra pinguis—Stahl’s phlogiston—was the material ingredient acted on by fire in Stahl’s theory of corrosion, combustion, and calcification.

Stahl thought of rusting as a slow-motion version of burning. He theorized that when a metal rusted, or when any combustible substance burned, it lost a portion of the phlogiston it was supposed to contain. An analogue to these processes was calcination, where heating of some metals produced what modern science calls an oxide and emergent eighteenth-century chemistry called a calx. Such calces were chemically identical to raw ores mined from the earth. According to Stahl’s theory, the refinement of metals by smelting ores with charcoal (a practical procedure long and well known in the mining and metallurgy tradition) involved the transfer of phlogiston from the charcoal to the ore, which took on phlogiston to become a refined metal. In calcination, when heating degraded metals into ores, the metals supposedly lost phlogiston to the surrounding atmosphere.

The theoretical phlogiston was the “matter of fire,” the particular “sulfurous earth” that accounted for combustibility. Materials that burned readily, such as wood, charcoal, or sulfur itself, did so because they were rich in phlogiston. Modern chemistry understands that flames die in sealed spaces when all the available oxygen has been consumed. Stahl explained this phenomenon in reverse: flames died when the burning material had released all its phlogiston, saturating the surrounding air to the point that it would no longer support combustion. Further, Stahl reasoned that phlogiston released into Earth’s air by burning was reabsorbed by plants and trees—thus, wood acquired the phlogiston, which made it so highly combustible.

The phlogiston theory was wrong, but it worked. It had the fundamental scientific virtue of accounting for a wide range of empirical observations with a single, self-consistent explanation. For that reason, most chemists of the mid-eighteenth century had grown firmly attached to it, and indeed it had been installed as part of the common knowledge of educated people. In his Critique of Pure Reason, Immanuel Kant appreciated Stahl’s theory as a milestone in the progress of science: “When Galileo caused balls, the weights of which he had himself previously determined, to roll down an inclined plane; when Torricelli made the air carry a weight which he had calculated beforehand to be equal to that of a definite volume of water; when Stahl changed metals into oxides, and oxides back into metals, by withdrawing something and then restoring it, a light broke upon all students of nature.”

Stahl’s chemistry was state of the art in the early 1760s, when Lavoisier was a student. But Lavoisier got his first definition of phlogiston from Rouelle, who had somewhat modified Stahl’s idea. In Stahl’s system, phlogiston was a “principle” that entered into the composition of mixts, while fire itself was an instrument that operated externally on the formation of mixts without entering into them. Rouelle’s chemistry course identified fire and phlogiston more fully with one another: “We recognize four elements: phlogiston or fire, earth, water and air.” At the same time, some of Rouelle’s precepts were 100 percent alchemical; for example, “The philosopher’s stone is nothing else but the result of the fermentation of gold with mercury especially charged with phlogiston. That is all I have to say of those transmutations which so many people without knowledge talk about.”

Lavoisier found Rouelle’s instruction both admirable and frustrating; he had recognized a need to “begin the study of chemistry all over again” when in 1766 he purchased one of Stahl’s Latin manuscripts—a treatise on sulfur. Lavoisier’s numerous annotations concentrated on the sections to do with calcination and combustion, on which Stahl’s phlogiston theory was based. In his direct study of Stahl, Lavoisier found for the first time a systematic, empirically grounded theory of chemistry. Though his own work would finally invalidate Stahl’s notion of phlogiston, Lavoisier understood the usefulness of Stahl’s concept: “For the first time in the history of chemistry, a theory was embodied in the facts it aimed to explain.”

IN 1793, AT around the same time that Lavoisier, haunted by the ghost of Marat, came under suspicion for his activities with the General Farm, Antoine-Nicolas de Caritat, marquis de Condorcet, went underground in the Paris house of a friend, Madame Vernet. Though lately a colleague of Robespierre and a member of the Committee of Public Safety, Condorcet had recently made himself a target of the Terror by publicly protesting the Jacobin Constitution adopted earlier the same year. He passed the nine months he spent in hiding chez Madame Vernet by drafting The Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind, a brief but sweeping survey of human development from prehistoric times to his own rapidly contracting present. The work complete, Condorcet emerged from his refuge, was promptly arrested, and soon died in prison, perhaps by suicide.

From a perspective not far from Lavoisier’s, Condorcet describes the broad influence of Newton: “We owe to Newton and to Leibniz the invention of these calculi for which the work of the geometers of the previous generation had prepared the way…. When we come to describe the formation and the principles of the language of algebra, the only really exact and analytical language yet in existence, the nature of the technical methods of this science and how they compare to the natural workings of the human understanding, we shall show that even though this method is by itself only an instrument pertaining to the science of quantities, it contains within it the principles of a universal instrument.”

Following an account of Newton’s mathematical explication of the law of gravity, Condorcet adds that “Newton perhaps did more than discover this general law of nature; he taught men to admit in physics only precise and mathematical theories, which account not merely for the existence of a certain phenomenon but also for its quantity and extension.” In these passages Condorcet is looking back—just over his shoulder—at the Enlightenment project of applying Newtonian methodology not only to transform all branches of the old natural philosophy into exact, mathematicized sciences, but also to reform all other branches of human knowledge—politics, metaphysics, history itself—on a similar basis. This impulse accounted for the creation of the metric system (on which Lavoisier was laboring while Condorcet wrote), as well as the more dubious achievement of the French Revolutionary Calendar, which, at the time of Condorcet’s writing, had tried to take history back to zero.

Before Lavoisier completed his fundamental work, chemistry was a Baconian rather than a Newtonian science—a vast anthology of facts (and pseudofacts) not very well marshaled by theory. Even in Lavoisier’s grip, chemistry would prove resistant to Newtonianization and to complete mathematicization as well. But Lavoisier was early to acquire the idea of modeling a new approach to chemistry on the huge advances that had been made in experimental physics; indeed, he did not completely distinguish the two disciplines, and in the beginning considered himself a physicist as much as a chemist. In 1766, during the early phase of his siege of the Academy of Sciences, he submitted an argument for increased emphasis on physics in the Academy: “experimental physics has escaped from the shadowy laboratories of earlier chemists* and…begun to take on a new form. Firmly based on experiments and facts, it has steadily advanced.” Already, Lavoisier intended to drive the shadows farther from the laboratories by establishing chemistry on a similarly firm base.

Kant, who like Condorcet regarded mathematics as the “universal instrument,” thought that all “genuine science” must have a mathematical foundation, and argued in his Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science that chemistry could not aspire to the condition of genuine science because it relied on collections of empirical, Baconian facts, rather than proceeding from theoretical axioms. By contrast, Lavoisier followed his teacher Lacaille in believing that mathematics itself derived from the quantification of observations about the natural world, and so should be understood as “a highly formalized way of stating empirically based knowledge.”

In the early 1760s (soon after the death of his mentor Lacaille), Lavoisier attended lectures given by Jean-Antoine Nollet, a physicist whose Cartesian approach to the subject would soon be eroded by his colleague and rival in the Academy of Sciences, George-Louis de Buffon, who adopted the Newtonian stance. Lavoisier got his grounding in the methods of experimental physics from Lacaille and Nollet, and during the years that he himself was striving for admission to the Academy of Sciences, the Nollet-Buffon controversy gave him his first full demonstration of the politics involved in the acceptance or rejection of new scientific ideas.

In the end, Nollet got the worst of it. Buffon, having recognized that Benjamin Franklin’s discoveries about electricity superseded Nollet’s ideas on the subject, used a French translation of Franklin’s work to undermine Nollet’s reputation, and soon was able to declare Nollet to be “dying of chagrin from it all.” Contentiousness over the issue actually brought electrical research in France to a deadlocked halt, a point that the progressive Lavoisier would not have failed to notice. Meanwhile, Buffon pushed past Nollet in his promotion of a Newtonian chemistry, which tried to account for chemical affinities as a sort of miniaturized version of the law of gravitation.

Lavoisier was, in general, suspicious of this sort of retreat into theoretical abstraction. His first sketch of a reformed course in chemistry, drafted when he was twenty-one, was modeled on Nollet’s course in physics—replete with experimental demonstration. Both Nollet and Lacaille were skilled designers of scientific equipment, and Lavoisier’s strong interest in precision instruments and the fine quantification they made possible began in his experience with these two teachers—here was one of the first features of experimental physics that he determined to export to chemistry. His notion of the application of mathematics to the quantification of scientific data also originated with Lacaille.

Scientific theory had to emerge from interpretation of precisely quantified data—as mathematics itself, in Lacaille’s view, derived from the organization of empirical information. “The only way to prevent errors,” Lavoisier wrote in his preface to the Traité élémentaire de chimie, “is to suppress reason, or at least simplify it to the greatest extent possible, for it comes entirely from us and if relied on can mislead us.” The suppression of reason may seem an odd enterprise for a luminary of the eighteenth-century Age of Reason, but what Lavoisier meant was to stress the importance of cross-examining theory whenever it drifted away from demonstrable fact. Such, for example, was the method he used to debunk mesmerism: driving a wedge between the mesmerists’ theory and the facts they claimed that it explained.

“Reason must continually be subjected to experimental proof. We must preserve only those facts that are given by nature, which cannot deceive us. Truth must only be sought in the natural connection between experiments and observations, in the same way that mathematicians arrive at the solutions of a problem by a simple arrangement of the givens. By reducing reason to the simplest possible operations and restricting judgment as much as possible, they avoid losing sight of the evidence that guides them.” Empirical facts, in Lavoisier’s methodology, would always be primary. Experimental demonstration, modeled on the rigor of geometric proof, would build those facts into a durable structure of ideas.

LAVOISIER WAS AS meticulous as Sherlock Holmes in the close examination he gave to his experimental proof. The exactitude of measurements assumed a paramount importance. For that reason, Lavoisier took an acute interest in refining the subtlety and the accuracy of his laboratory equipment.

Early in the seventeenth century, the Belgian chymist van Helmont had performed an experiment that many eighteenth-century scientists still believed to be a demonstration of the transmutation of water into earth. Van Helmont potted a 5-pound willow in 200 pounds of soil, closed the soil container, and added nothing but rainwater. At the end of five years the weight of the soil was unchanged, but the willow had increased to a weight of 169 pounds. The role of photosynthesis in plant growth was nowhere near discovery in van Helmont’s day, nor had the phlogiston theory (which Stahl did use to account for plant growth) yet made its appearance. Van Helmont reasoned that the water must have been transmuted into earth in order to generate the increased wood of the tree.

Though the transmutation of metals was already discredited by the time of Lavoisier’s early experiments, the notion of transmutation of other substances persisted as a corollary of the Aristotelian theory of the elements, which had not been definitively replaced. Proceeding from the theory that water could be transmuted into earth, scientists following van Helmont explained the observation that distilled water always left a solid residue in the vessel in these terms.

In conjunction with his studies of the public water supply in the late 1760s, Lavoisier became interested in the transmutation question. He suspected that the solid residue left by distillation more likely came from glass dissolving from the vessel during boiling. To prove the point, he boiled three pounds of water for one hundred days in a glass vessel called a “pelican” (its curved, hollow handles, which worked as distillation tubes, resembled the wings of the bird). At the end of the experiment Lavoisier found that there was indeed a residue, but its weight was almost exactly equal to the weight lost by the pelican. The sum of the weights of the pelican and its contents had not changed. The shift of weight from the vessel to the contents was accounted for by grains of salt in the residue. Lavoisier’s hypothesis—that material dissolved from the vessel furnished the solid residue of distillation, rather than any transmutation of one element into another—was so demonstrated.

This early experiment had a minor flaw: while the weight lost from the pelican was 12.5 grains, the weight of the salts in the residue was 15.5 grains. Lavoisier permitted himself to overlook the discrepancy, or rather (somewhat contrary to his methodological rhetoric) he allowed his governing theory to overrule it.

The theoretical postulate involved was the conservation of matter, also known as the conservation of mass. Lavoisier did not formally express it until 1785: “Nothing is created either in the operations of art, or in those of nature, and it may be considered as a general principle that in every operation there exists an equal quantity of matter before and after the operation; that the quality and quantity of the constituents are the same, and that what happens are only changes, modifications. It is on this principle that is founded all the art of performing chemical experiments; in all such must be assumed a true equality between constituents of the substances examined, and those resulting from their analysis.”

Though Lavoisier generally gets credit for the authorship of this principle, others had conceived it before him. The seventeenth-century chymists, notably van Helmont, Starkey, and Boyle, had a dawning awareness of the importance of weighing and measuring materials before and after an experimental process, though their methods and their measurement devices were not so precise. In 1623, Francis Bacon declared, “Men should frequently call upon nature to render her account; that is, when they perceive that a body which was before manifest to the senses has escaped and disappeared, they should not admit or liquidate the account before it has been shown to them where the body has gone to, and into what it has been received.” And as early as 450 B.C., Anaxagoras argued, “Wrongly do the Greeks suppose that aught begins or ceases to be; for nothing comes into being or is destroyed; but all is an aggregation or secretion of preexisting things; so that all becoming might more correctly be called becoming mixed, and all corruption, becoming separate.”

Anaxagoras’s “nothing comes into being or is destroyed” is very close indeed to Lavoisier’s “nothing is created.” The idea of conservation of matter had been around for many centuries before Lavoisier installed it as the centerpiece of his experimental method. (He depended heavily on the principle for fifteen years before he announced it, perhaps because he simply assumed that its validity was common knowledge.) But Lavoisier, beginning with this experiment in the distillation of water, deployed the principle much more strictly and consistently than any scientist had ever done before him.

Lavoisier’s work in finance continually reinforced his commitment to the idea of balance. In all phases of his career, he was an exacting accountant. An analogy to physics encouraged him to view money as “a fluid whose movements necessarily end up in a state of equilibrium.” Equilibrium governed the balance scale on which the materials of chemical experiments were weighed, and increasing the refinement and the accuracy of this instrument was for Lavoisier a perpetual concern.

BY THE EARLY 1770S, Lavoisier’s preliminary investigations had progressed halfway through the sequence of four Aristotelian elements. The mineralogical surveys he conducted with Guettard broadly covered the earth element. His studies on behalf of the Academy of Sciences of the Parisian water supply and the general properties of water covered the element of water as thoroughly as could be done at the time. Now Lavoisier turned to the study of air. More work in pneumatic chemistry—the chemistry of gases—had been done in England than in France at that point. Several different gases present in the atmospheric air had been isolated, though with no terminology to identify them and no precise understanding of what they were. The various cloudily identified gases were still considered to be inert rather than reactive in chemical combinations. Georg Stahl, whose chemistry remained the most advanced on record, believed that air was merely an environment surrounding chemical reactions, not an active ingredient in them.

In France the 1770s saw a resurgence of a practice that had appeared a century before in the court of Cosimo III, grand duke of Tuscany: a scientific fad for incinerating diamonds. The Tuscan experiment subjected six thousand florins’ worth of diamonds and rubies to twenty-four hours of extreme heat and found that while the rubies were unaffected, the diamonds had vanished without a trace. In the 1770s, French chemists, Lavoisier among them, took up this ostentatiously extravagant line of research.

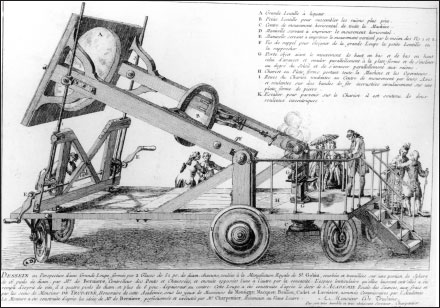

The equipment involved a huge contraption, vaguely resembling a Roman catapult, that focused sunlight via two enormous lenses, called “burning glasses,” to concentrate intense heat on the crucibles of jewels. The scientific operators wore smoked goggles to protect their vision from the brilliance of the burning. This engine was wheeled into the Jardin de l’Infante, outside the Academy of Sciences quarters in the Louvre, and close beside a popular public promenade along the Seine. Onlookers were plentiful, and the ladies were impressed (and perhaps dismayed). Of course, there was much more dramatic interest in the burning of diamonds than if the scientists had been applying their incendiary beam to ordinary lumps of coal.

It was soon determined that the presence of air was required for the diamonds to disappear or be consumed. Diamonds effectively sealed from the atmosphere were always recovered intact. Today we know that since diamonds are a form of carbon, sufficient heat makes their carbon combine with oxygen and vanish into carbon dioxide. Lavoisier must have suspected that the diamonds were disappearing into gases, for in the spring of 1773 he conducted a series of experiments in which he tried to capture any gases that might be emitted from burning diamonds under a glass bell. But his glass vessels shattered in the extreme heat of these experiments, the gases could not be collected for measurement, and the cause for the dissolution of diamonds could not be firmly defined.

THEN LAVOISIER TOOK note of a more promising line of investigation in pneumatic chemistry—one involving the calcination of metals. Stahl’s phlogiston theory asserted that metals, when heated to form calces, released or lost phlogiston. Why, then, did the resulting calces weigh more than the original quantities of metal that went into their formation? Phlogiston was supposed to have a weight (though as it did not really exist, no one had so far managed to weigh it). So the increased weight of a substance supposed to have lost phlogiston violated the principle of conservation of matter—which to Lavoisier was absolutely axiomatic.

Because of this inconsistency, explanations of calcination in terms of phlogiston grew more and more tortured, yet Condorcet was articulating the prevailing view when he wrote, in reaction to the challenge Lavoisier was beginning to formulate, “If ever there was anything established in chemistry, it is surely the theory of phlogiston.” Turgot, alongside his career as economist and Physiocrat, was also accomplished enough as an amateur chemist to be invited by Diderot to contribute chemical articles to the French Encyclopédie. “The increase in weight occurring in metal,” he wrote in his entry on the weight gain of metallic calces, “is due to the air which, in the combustion process, combines with the metallic earth and replaces the phlogiston, which is burned and which, without being of an absolute lightness, is incomparably less heavy than air, apparently because it contains less matter.” This passage is a difficult one. Phlogiston, now that it needed both to have weight and to be lighter than air, was well on the way to becoming a deus ex machina of chemical reactions—not to say a magical solution.

The “burning glasses,” capable of producing intense heat.

The exacting mind of Lavoisier was quick to home in on small weaknesses of this sort. In February of 1773, he opened a new laboratory notebook with a plan for a research program in this area:

Before beginning the long series of experiments that I propose to myself to do on the elastic fluid which releases from bodies, be it by fermentation, by distillation, or finally by all kinds of combinations, as well as on the air absorbed in the combustion of a great number of substances, I believe I ought to put down some reflections here in writing, to form for myself the plan that I must follow.

However numerous are the experiments of MM. Hales, Black, Mac Bride, Jacquin, Crantz, Priestley, and de Smeth on this subject, it nevertheless remains necessary that they should be numerous enough to form a complete body of theory…. The importance of the subject has engaged me to again take up all this work, which strikes me as made to occasion a revolution in physics and chemistry. I believe that I should not regard all that has been done before as anything other than indications; I propose to repeat everything with new precautions, so as to connect what we know about air which fixes or releases itself from bodies with other acquired knowledge and to form a theory.

The works of the different authors which I have just cited, considered from this point of view, have presented to me separate sections of a great chain; they have joined together a few links of it. But a great sequence of experiments remains to be done, to form a continuity.

Despite his declared suspicion of theory, Lavoisier’s most durable achievements would be as a theoretician—not as a discoverer of previously unknown facts. In 1773, when he made these notes, he already seemed to know it.