Ferguson and the Power of Liberation

If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.

—LILLA WATSON

When the people of Ferguson rose up in August of 2014, years of pent-up anger poured into the streets, fully righteous against police violence and murder. Michael Brown, an unarmed teenager, was shot in a street near his home and left to die, lying out in the sun for four hours and twenty-five minutes. The anger of the protestors combined with the militarism of the police created a dance of power that went on for weeks, months, and then years as people all over the country woke up to the reality of a country fractured by racism.

The struggle in Ferguson was waged by poor Black people who’d had enough. Day after day, night after night, hundreds gathered in vigils, marches, and lines with their hands in the air chanting, “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot.” They laid bare their pain and vulnerable bodies to tear gas, stun grenades, rubber bullets, live bullets, police clubs, and arrests. The people refused to back down, and in doing so, birthed a new era of the Black liberation movement, which had been seeded two years earlier, in February 2012, when Trayvon Martin, another unarmed Black teen, was killed by George Zimmerman, who was acquitted under Florida’s Stand Your Ground law. Then in July 2014 Eric Garner was killed by New York police for selling cigarettes. They kneeled on his neck as he yelled “I can’t breathe,” but they did not let up, murdering another Black man and father.

When Michael Brown was killed, the movement exploded. It was out of the box, and it was not going back.

Ferguson was not about size, but heart. The resistance was both structured and organic. There was a willingness to be visible and raw in pain, sorrow, and anger, demanding that the world know Black Lives Matter. Police murders of Black and Brown people matter, and real accountability for those responsible matters—not just in Ferguson, but in every community across this country.

Ferguson was about action. It brought together many sectors, including youth, faith, labor, and peace and justice groups. Some people of faith initially held back in condescension, but with the fierce leadership of Reverend Traci Blackmon and Reverend Osagyefo Sekou, they rose up in the spirit of Moral Monday to face the police. Reverend Sekou, a religious leader who grew up in St. Louis, moved them by calling for a willingness to take militant, nonviolent direct action from a place of deep abiding love against the system.

Deep abiding love against the system. The people in Ferguson did not want to play by the rules because the rules did not serve them. Social change requires a real challenge to state power and the institutions that hold up racism and supremacy. In my life as an organizer, I have often spoken about dismantling structures of oppression while building structures of liberation. We can’t do one without the other.

In Ferguson local organizers were wary of outside groups and demanded that white allies recognize their privilege. My experiences in Ferguson caused me to reflect on how much I still must learn about building an anti-racist world. These changes will not come easy. Centuries of structural and systemic oppression are so deeply embedded that neither white folks nor many people of color truly understand all the ways in which racism and capitalism have made us sick. Dismantling the unjust structures that keep huge numbers of our population in trauma, impoverished, and uneducated will take intention, resources, and healing work.

The questions we must ask ourselves are: What am I waiting for, and how can I contribute? Or better yet, thinking again about the words of Reverend Sekou, who counseled clergy on how to respond to Black youth who are angry or upset—simply tell them, “I’m sorry it has taken me so long to show up.”

Ferguson October and Moral Monday

On August 9, the day Michael Brown was killed by officer Darren Wilson, community members gathered around the eighteen-year-old’s body, which lay for over four hours where he fell on Canfield Drive in Ferguson, a predominantly African American suburb northwest of St. Louis. The people were distraught; another young Black man was dead. The following evening there was a peaceful candlelight vigil and scattered incidents of property damage. In response the police sent 150 officers in riot gear, and thirty-two were arrested.1 This was enough fodder for the national media to start broadcasting images of civil unrest with story after story about looting, not the peaceful protests.

By the third night officers wearing fatigues and riot gear tear-gassed a peaceful demonstration and fired stun grenades into a crowd. Reporters were arrested along with protestors, and the community’s calls for accountability were not answered as the militarized presence increased. By August 17 the National Guard was called in, and even before then, Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles—MRAPs—were rolling through the streets. These huge tanks were developed during the Iraq War to withstand land mine detonations and IEDs. Police officers were carrying both shotguns and rifles, prompting servicemen and -women watching this unfold on TV to observe that they packed less heat while at war.2

Elected officials got involved, speaking out, but their stature did not always protect them. When St. Louis alderman Antonio French tried to document the protests, he was dragged from his car, thrown to the ground, and arrested for unlawful assembly.

Throughout August and September the protests continued, sometimes sporadic and sometimes sustained, while a series of political events unfolded, including a visit by Attorney General Eric Holder, fact-finding delegations from Amnesty International, and statements by President Obama. New grassroots organizations emerged while long-standing ones solidified their support for the movement.

One thing that made Ferguson special is that grassroots groups maintained the bulk of the power even when the movement became sophisticated and spread across the nation. Two of the long-term organizations in the St. Louis area became anchors for much of the work. The Organization for Black Struggle, or OBS, had been in St. Louis for over forty years, with a rich history of political and cultural action.3 OBS was the hub for art making, cultural work, and strategizing among the Black organizers. The other local group, Missourians Organizing for Reform and Empowerment, or MORE, founded in 2010, was a community-based organization working in the legacy of ACORN that focused on economic justice issues like housing and foreclosures. New local groups emerged as well, many of them Black- and youth-led, including Hands Up United, Millennial Activists United, and lesser-known groups like Lost Voices, Black Souljahs, Freedom Fighters, and Tribe X.4

When historic people-powered movements like this one rise up, there are patterns that tend to repeat. You’ll often see a grassroots groundswell from the margins that is ignored, shunned, or criminalized; then grassroots organizers with skills to offer start hitting the ground. As time goes on, national groups send people in, generating action alerts, starting publicity and fund-raising campaigns while more established local groups translate the resistance into political reforms. During this process, money became a big issue in Ferguson, a community that had none. While there were attempts to redistribute resources locally, it proved difficult to create a structure to do this well.

When everyone gets involved like this, it’s clear that a real movement is under way. In September plans were being made for a national convergence called Ferguson October, a four-day mobilization with marches, speeches, and direct actions that would culminate on Monday, October 13.

I was at home in Austin, Texas, on the day Michael Brown was murdered, and like many others I watched in horror at the militarized response to a community’s outcry for justice. I checked in with a friend in St. Louis, Jeff Ordower, the executive director of MORE, who felt it was not the time for white organizers to come in yet. I understood.

When the public call for Ferguson October was issued, I knew I would be going. I contacted my friend, the artist Laurie Arbeiter, and we agreed to meet in St. Louis.5

After landing at the airport, I picked up some flowers for the Mike Brown memorial. Driving into Ferguson, I made my way up West Florissant Road, where much of the protesting had occurred, and saw the QuikTrip store that burned on August 10. I turned onto Canfield Drive and silently got out. I was struck by the tranquility of the neighborhood, with small houses, apartment complexes, and green spaces. The memorial was in the middle of the street, stretched out along the double yellow line. It was made up of candles, flowers, stuffed animals, a basketball, and some signs. One of them said, BUT WHERE IS JUSTICE? Over on the sidewalk there was a huge pile of stuffed animals around a light pole with a picture of Mike Brown wearing mortarboard from high school graduation. He was supposed to start college a few weeks after his death.

I didn’t stay long. I placed my flowers on the memorial and took a few moments to honor the life of Michael Brown, whose death had changed our world.

I headed over to MORE’s offices in the World Community Center in St. Louis, where some of the organizational efforts were being housed, and was impressed to see that the building held offices for many social justice groups including Show Me $15, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and the St. Louis Palestine Solidarity Committee. These offices had become a major infrastructure hub, including legal and jail support, material resources, food, training, and meeting space for the growing resistance. The place was buzzing, with people everywhere.6

Ferguson October was a collaboration among OBS, MORE, and Hands Up United, a new group funded by outside forces, creating some complicated dynamics. A gift to the movement arrived as Maurice Mitchell and Mervyn Marcano, two organizers from out of town, provided a vision for the weekend and skillfully bridged the divide between local and national organizers. As the challenges with Hands Up United continued, the Don’t Shoot Coalition was formed, growing to over 150 local organizations working for political reforms, including a proposed set of “rules for engagement” for the police.

Three days before Ferguson October began, I attended my first meeting, with Celeste Faison, a young Black woman from Ruckus, facilitating. We discussed the planned direct actions for Monday, and I was asked to be an action coordinator. I was hesitant, unsure about taking the lead as a white woman who had just arrived and didn’t know the turf. I asked if I could support the trainings and actions without being a coordinator, which everyone was okay with.

Emotions were high that evening after an off-duty police officer shot and killed VonDerrit Myers Jr., an eighteen-year-old Black teen, in the Shaw neighborhood just south of downtown. Vigils and marches were being organized and would continue each night.

On Saturday we trained hundreds of people in nonviolent action. As with all my trainings, I urged as many white people to risk arrest as possible, knowing it helps them grapple with their privilege. On Sunday we marched and rallied in downtown St. Louis. Speakers addressed the crowds with incredible passion about the need for justice in a city of injustices. The Ferguson police had been harassing, arresting, and financially sapping Black folks for years. It was a lived experience that was affirmed by the Justice Department’s investigation, released eight months after Brown’s death, which the New York Times characterized as so scathing, and delineating so many constitutional violations, that the city was being asked to “abandon its entire approach to policing.” Amid other findings, the investigation “described a city that used its police and courts as moneymaking ventures, a place where officers stopped and handcuffed people without probable cause, hurled racial slurs, used stun guns without provocation, and treated anyone as suspicious merely for questioning police tactics.”7

On Sunday evening there was a mass meeting at the Chaifetz Arena with over a thousand people attending. The speech given by the president of the NAACP was interrupted by some youth in the audience who demanded to take the stage. Many in the crowd roared “Let them speak!” as others tried to shut them down. Within minutes Tef Poe and Ashley Yates had the stage. Poe was a local rapper who became a key person in Hands Up United, while Yates was one of the founders of Millennial Activists United. They talked about anger, pain, and the impact that police violence had on them personally and on the community. They then declared, “This ain’t your daddy’s Civil Rights Movement. We’re doing this one our way.”

To me this moment said everything about the organizing in Ferguson. It was grassroots, Black-led, youth-led, and fierce. They were not taking no for an answer.

The young folks announced there would be a march that night launching from the VonDerrit Myers memorial. By 11 PM close to a thousand were gathered there. The march led to St. Louis University, where we poured into the Clock Tower Plaza, a big circular area around a fountain.8 This was the beginning of a sit-in that lasted about a week and ended with an agreement by the administration to improve its African American studies programs and increase financial aid.9

That early-morning sit-in was the beginning of the Moral Monday Day of Action, named in solidarity with the movement founded by the Reverend Dr. William Barber in North Carolina. At least nine actions rolled out that day. I was supporting the plan for civil disobedience at the Ferguson Police Station, led by Reverend Sekou, whom I had worked with at United for Peace and Justice. He had been living in Boston, but the uprising convinced him to move back home, and it was good he did. Sekou is a small man but a huge force. He is not afraid to speak his mind and call out the clergy for their inaction. At heart he is a revolutionary who knows the system is as guilty as hell!

I arrived at the church and sat quietly in a back pew as he prepared the church leaders to depart for the police station. His call for nonviolent, respectful, righteous action was strong. His words reminded me of my early days of civil disobedience, when the calls against the US’s dirty wars in Central America were led by religious leaders and strongly rooted in spirit. I was feeling at home and glad for the opportunity to support this strong leader. For his part, Reverend Sekou was equally glad that I was there; he liked to call me the Jedi Master. I knew he was not being flippant, because it so happens that on the airport shuttle after arriving in St. Louis, I ran into Bishop John Sellers and his wife, Pamela, friends of the reverend. As I was telling them about my work, they said, “We know you! You’re the Jedi Master that Sekou was telling us about.” Needless to say, I was both embarrassed and honored.

The time to march had come. It was a gray, rainy day, but we were not deterred. On the way to the police station we passed a few commercial strip malls with locally owned stores and corporate chains like Subway, which made a hell of a lot of money off the protests. Over a hundred religious leaders in their robes and brightly colored adornments flowed into the streets. The police station was barricaded off, including the door we wanted to get to. As we assembled out front, a man lay down and we drew chalk lines around his body. We all chimed in to sing “Ella’s Song” inspired by the civil rights leader Ella Josephine Baker, written by Bernice Johnson Reagon, and recorded by Sweet Honey in the Rock. Ella Josephine Baker was one of the most influential organizers of that era. She worked with Dr. Martin Luther King at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and was a founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Baker is an unsung shero and role model for all who want to better this world. The words of the song reminded us that we cannot rest until the lives of all children of color are as important as the lives of white children.

The clergy linked up their arms and moved forward toward the line of police—many of whom were dressed in riot gear—offering to take confessions and demanding to meet with the police chief. Among them was Cornel West, who had asserted the night before at the town hall meeting that he did not come to talk, but to get arrested. The first wave of clergy was indeed arrested, and another wave stepped right in to replace them. This was a powerful moment, because it was some of these same clergy who had aligned with the conservative establishment early on after Brown’s death, creating lots of conflict. But now they were putting their bodies on the line.

I supported multiple other actions throughout the day, and all told, sixty-four people were arrested on Moral Monday. The uprising in Ferguson had become an organized, effective movement, and the world was watching.

The Power of Learning Strategies for Dealing with the Police

I was grateful for the young men and women in Ferguson. They were fearless, from the leaders and organizers down to the kids who just showed up. They took whatever space they could and moved skillfully, emboldening those who might follow. They chanted, “We’re Young, We’re Strong, We’re Marching All Night Long,” and they meant it. Simply put, the youth of Ferguson did not back down when they faced police or politicians. I watched people kneel in the street, laying their bodies bare to whatever the police might choose to do. They did not care about the media. They did not care about messaging. They did not care about making friends with politicians or bankers. They had one another, and that was enough.

And of course, they were not rising up against police violence alone. In the words of one of their chants, “The Whole Damn System Is Guilty as Hell.” They were rising up against the school-to-prison pipeline and the institutions that criminalize and cage. They were calling for an end to laws and policies that keep communities in the cycle of poverty. They were calling for an end to police abuse and racial profiling. They were demanding accountability for police violence and community-based alternatives to incarceration.

The youth were fighting for their lives. According to a 2017 report, in 2016 young Black males were at least nine times more likely to be killed by police than other Americans.10 African Americans are four times as likely to experience the use of force during encounters with the police, and one in three African American men will go to jail at some point in their lifetime.11 The criminalization begins at a young age. In many of the nation’s largest school districts, including New York and Chicago, there are more police officers per school than counselors, and students are arrested—arrested!—for offenses like talking back to their teachers and “disorderly conduct.”12

As someone who has spent decades interacting with the police, I have a deep understanding of the fear of law enforcement, yet cannot imagine what it is like to be targeted by the police just for being Black, knowing that the badge is a license to kill.

Despite being white and privileged, I have felt vulnerable to state terror and violence, from being labeled a terrorist by the media, to being targeted by the police, FBI, and Homeland Security, to the times I have feared for my life. Once such frightening incident occurred in New Orleans a few months after Katrina. A bunch of us were cleaning up after a memorial service for Meg Perry, a young volunteer at Common Ground Relief who was killed in a tragic bus accident. We held a beautiful service and tree planting with Meg’s family in the garden she had worked so hard on. Afterward I left to give people a ride home and got a call that the police were at the garden.

I raced back to see everyone lined up with their hands on the police car. I walked up slowly, asking respectfully for whoever was in charge. I was answered with, “Shut the fuck up, get your hands up!” This cop was screaming and pointing his gun at me.

As asked, I slowly walked toward his car. He pushed me up against it and put the gun to my head. I breathed as deep as I could. I noticed that Josh, an eleven-year-old kid, had a red dot on his head, the laser marker for a gun. The cop stepped back as more squad cars rolled up, and as they approached I called out, “Is there a reasonable cop among you? Please come talk to us!” Finally, one did. I asked if he remembered the recent bus accident and explained this was the memorial service for the woman who was killed. The other officer was defending himself now, saying he thought we were looters. Maybe one could make that mistake, but all it takes is asking what we’re doing, not running in pointing guns. You can see how easily people get killed by cops.

Learning how to deal with police is not a joke or a game, but something that can save your life. The movements against police brutality and mass incarceration continue to grow, but until the system changes, the police will do what they want. They expect the blue code of silence and worry about repercussions or lawsuits later.

I have dealt with officers who are brutal and vicious, those who are respectful, and everything in between. My approach to cops is not so much about Fuck the Police, but appealing to them to put their guns down and join the people. Until then, they are complicit, no matter how decent a person they might be.

Facing the police has become an inevitable part of protests and mobilizations. Plans are necessary, but you must also plan for unpredictability. And if your plan from the beginning is to non-cooperate with the police, unpredictability is inevitable. Non-cooperative acts require courage and bravery, which is what I saw every single day in Ferguson.

OUT OF THE TOOLBOX

Tips for Dealing with Police

In the context of protests, mobilizations, and uprisings, we are often confronted with the police or National Guard. There are many different strategies for dealing with law enforcement, but I prefer the ones that focus on mitigating harm.

When police are on the scene, pay attention to their body postures and movements. Learn to read their energy. Are they chill and standing down, or agitated and poised for attack? Do they have horses or dogs on the scene?

Pay attention to their gear. Do they have batons or handcuffs at the ready? Do they have tear gas masks? Are there horses or dogs? What other weapons or vehicles have they brought onto the scene?

You may want to bring protective gear of your own—goggles, masks, and earplugs.

Make sure you have scouts who are looking around to see where the police are staging in locations that are out of view.

Know your exit strategy from the area. Look around to find places to take cover to protect yourself or nearby stores you can duck into.

Pre-designate people to document with cameras, and organize legal observers who will be a public presence to document the events.

Remember that police work with command-and-control strategies. They expect people to do what they say, and can get agitated and escalate the situation when we don’t.

Police typically follow a chain of command, so learn what their uniforms and ranks mean, and observe when the superiors start issuing directions to the troops.

In some contexts you may choose to empower someone to be a police liaison. This person keeps the channels of communication open and buys time. When I have taken the role of police liaison, here are strategies that have helped:

I access the part of myself that is authoritative and confident. It might seem counterintuitive to act authoritatively toward officers, but they are used to following orders and clear communication and direction. It’s possible that this strategy works for me largely because I’m a white woman.

I rarely approach the police alone. It is always good to have a team, with one person speaking and the others witnessing.

I approach them with respect, while also asserting our right to do what we are doing. Always assert your rights.

If they say you are violating a code, ask them to show you the code.

Each situation is different. If the officers are stationary and calm, it might not be necessary to speak with them. If the action is more intense and it seems like the officers might come charging in, I try to speak with them and attempt to de-escalate their response.

If the officers begin to escalate, I try to speak with them and point out that they’re making the situation unsafe. Safety is a key talking point. If one cop is escalating, it has worked for me in the past to ask a superior to remove them.

I sometimes tell the officers about the reason we’re taking action and ask if they know anyone who is affected by this issue to assess if they’re sympathetic to the cause.

Remember that officers expect people to do what they’re told, even if it violates their rights. Many cities now take out insurance policies for major political events. This shows that they plan to violate people’s rights and ensures they’ll have money to pay off lawsuits.

The Non-Indictment

In the days after Brown was killed, the action in the streets was a raw uprising of the people. By the time of the non-indictment on November 25, the people were organized and powerful, and the movement was national, with almost a hundred actions taking place across the country.

In early November I was back at home in Austin but still inspired by the actions in Ferguson. I reached out to my dear friend Michael McPhearson, the executive director of Veterans for Peace.13 We had served together as national co-coordinators of United for Peace and Justice, and now he was one of the cofounders of the Don’t Shoot Coalition. I let him know I was interested in coming back to St. Louis to provide more training and support. He brought my request to the Don’t Shoot Coalition, which extended an invitation to come.

I made my arrangements to arrive on November 6 and immediately connected with Julia Ho, one of the organizers at MORE who was working to train and develop young organizers from Tribe X, Freedom Fighters, and Black Souljahs. All of these were locally led youth organizations formed after the uprising.14

Many of these young people were living together in an apartment with limited resources. We went over for a visit and were greeted warmly. We hung out for a while as I asked questions about how they were doing. I could feel the edges of trauma all around. These kids had been living their lives disempowered and pissed, and now everything had changed. They were passionate, if exhausted. I shared with them how much respect I had for their street skills. They were the ones who led a lot of the marches during Ferguson October, including the one that converged at St. Louis University for the sit-in.

The following day I arrived at the training space early to set up. As streams of people began to file in, it was clear I couldn’t do the training as planned for so many. This is the kind of problem that’s good to have. Michael and Montague Simmons from OBS opened up, and then I shared the history and power of direct action. We used Q&As to address issues around the police, health, trauma, and how to stay safe. I spoke about self-organizing and the importance of working in small groups. We began to lay out a vision of geographically based organizing and how to plan actions around specific locales. We talked about the importance of being prepared for any scenario, including police violence and arrest, by packing a go-bag that had water, a bandanna, a map, an energy bar, protective gear for your eyes, a battery charger for your phone, and so on. Before we closed, we suggested that people get their friends together to circle up and form affinity groups.

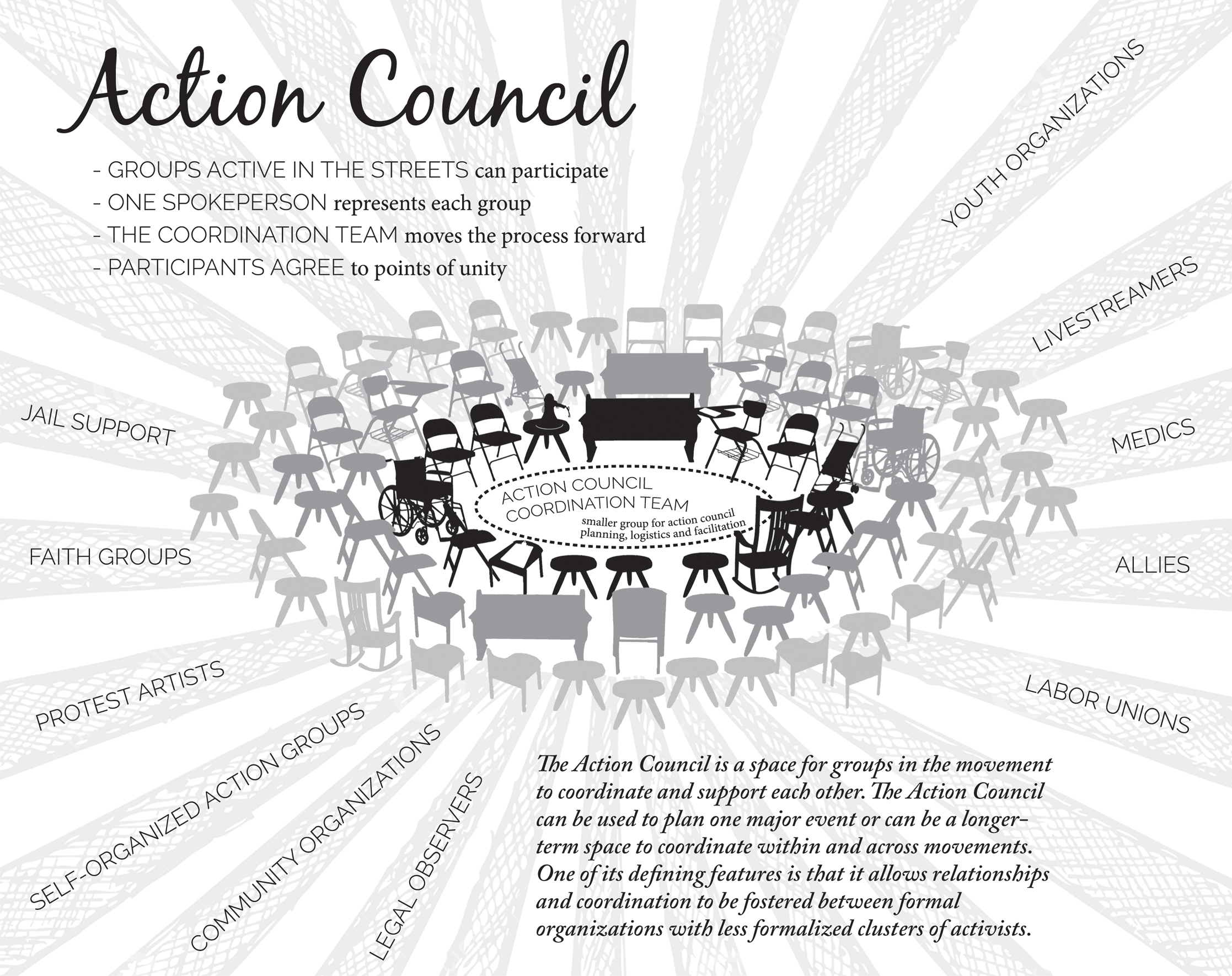

The meeting was a hit. Afterward Michael, Montague, and I talked about developing a series of mass meetings, mass trainings, and an action council as we prepared for the grand jury verdict. Our intent was to have spaces where both unorganized individuals and new groups could come together. Over a thousand people were trained over the course of those meetings, which created an open container for people who had not yet been in the streets. We developed a common framework for mass direct action that was principled, militant, and practical, emboldening people to take to the streets in organized groups that could also create their own actions. This effort also sent a strong message to the local power structure, including the politicians and police, that the movement was getting increasingly organized.

This organizing was similar to the affinity group model I learned in the 1980s during the Central America antiwar movements, and it has also been used in the anti-nuclear movement, the Global Justice movement, Occupy Wall Street, and others. These models embrace the principles of direct democracy, self-organization, shared power, and mutual aid. In the US the model has been used predominantly by white folks—though its core principles really trace back to Indigenous ways that have been used all over the world. It seemed clear to us that the emerging action council would need to be an explicitly anti-racist space convened and facilitated by people of color.

Once we got started, we learned that the people were hungry to be organized. We were able to cement a number of affinity groups while also teaching young leaders how to facilitate consensus meetings. Two young Black women, Kayla Reed and Brianna Richardson, became excellent facilitators. Both were new to the movement, politicized by the uprising—Kayla had been a pharmacy technician and Bri had worked in corporate America. The nights in the streets changed their lives. Kayla facilitated the first big meeting, and I was thrilled to see that sixteen newly formed affinity groups representing hundreds of people showed up. We called this emerging structure the Ferguson Action Council, and a version of it, now called Action St. Louis, is still around today.15

One of the unforgettable actions prior to the non-indictment was a die-in outside the Tivoli Theatre, on a popular strip of Delmar Boulevard near Washington University. The plan was for us to play the roles of the cops shooting, people dying, and people chalking the bodies and laying down flowers. We divided into two marches, each with a set of props for the funeral procession.

It was a cold, wet, and lightly snowy day. We carried the coffins, which were donned with bright, vibrant flowers.16 My group had to walk on a sidewalk where construction was under way, and one in our crew, a larger man named HJ, pulled up a wooden construction stake and started marching with it. The stake was supposed to be a “sword” to match the large wooden shield he and others carried to protect themselves from police batons. I was, like, Oh shit—being a large Black man with a pointed stick was the kind of thing that could make you a target. I sidled up to HJ and said, “Do as you wish, just know you could become a target.” He did not give a fuck at all.

Illustration courtesy of Emily Simons.

Our two groups convened at intersections a few blocks from the theater. As we arrived, we deployed our traffic blockers and poured into the street. Those of us playing the cops shouted and threatened as the people put their hands in the air. As we “shot” them, bodies fell onto the street. The snow was coming down softly around us as dozens of onlookers stopped to watch. We carried in the coffins and flowers and mournfully chalked the bodies. Dhoruba was on the bullhorn, telling onlookers his story about what it was like to be a Black man in this world, the sorrow, anger, and pain. At one point I looked over and saw HJ just standing there, the shield and sword lowered at each side, a tear coming down his cheek. Gazing into the street at our dramatic scene, he said, “I didn’t know it would be so beautiful.” I, too, felt the tears in my eyes.

Die-in action outside the Tivoli Theatre on Delmar Boulevard in St. Louis, November 2014.

This is the power of direct action. When we create acts of beautiful, meaningful resistance, something inside us changes. It is that bittersweet knowing that we can create beautiful worlds, and that we can make it so, every day, using conscious choices.

The sweet moment was broken as the amplified voice of the police blared, “This is an illegal demonstration. You must leave now, or you will be arrested!”

We prepared to complete our action, chanting, “Stand Up, Sit Down, We Do This for Mike Brown!” As planned, these words prompted the dead people to rise up and join the chant. We formed back into one big march and headed right toward the police, flowing around and through the spaces in between their cars. We knew the best way to confront the fear and potential danger was to move right toward it with our love and light. That is just what we did, and the police could do nothing about it.

We didn’t know when the verdict would be announced, but as November passed, you could feel it coming. There was tension all around. Businesses were boarding up, schools prepared to close, barricades appeared around the Justice Center in Clayton as well as City Hall. There were rumors of gang violence. Protests continued every day and night at the Ferguson police station as helicopters flew overhead, shining bright lights down on us. We produced an online map pinpointing fifty possible action targets including police stations, political offices, and businesses. The map also included safe spaces and hospitals. My own plan was to be at the Ferguson Police Department whenever the news came in.

Finally we got word from the Brown family that a verdict would be announced the next night, November 25. When I arrived at the police station, it was already a crazy scene with hundreds of people and dozens of media outlets with their tents and trucks. It was cold and dark; you could cut the tension with a knife. The crowd was in constant motion, people moving here and there, pacing back and forth. When the announcement came, I was standing next to Mama Cat, a local woman who had been in the streets since August, cooking for and feeding the people. She was listening on her phone, repeating back what was said: There would be no indictment. Darren Wilson would walk away free.

The crowd roared, “NO. NO. NO.”

Lezley McSpadden, Mike Brown’s mom, was standing on the back of a truck amid the crowd. She broke down. Mike Brown’s father held her as they both cried. The crowd was stunned and slowly woke with anger. Things started to fly—bottles, signs—toward the line of riot police. In a surreal moment I looked at a red-lighted sign over the road that said SEASON’S GREETINGS with the large line of riot police below. This was certainly no holiday season.

The crowd spread and scattered. A grouping of giant military tanklike vehicles moved north on South Florissant toward the crowd. Tear gas was flying. Shots were fired—from where, no one knew. People were yelling and screaming. Within moments you could see a fire burning down the road: A police car was ablaze.

I was with Julia and Derrick Laney from MORE. Derrick needed to get a ride to his car. We got to my car and drove toward Derrick’s, but as we turned onto that street, it was lined with cops, their guns raised. I backed up. Once the police were redeployed to another street, Derrick got to his car, and now I needed to drive my friend Julia to her car. This was another fool’s errand. As we drove through an alley, a line of cops raised their guns at us. The red dot of a sniper laser was on my dashboard. I was, like, Julia, we’re getting your car tomorrow. We got the hell out of there and made our way to a church, one of the pre-designated safe spaces. We caught our breath and then headed back out, trying to make our way down West Florissant. Horns blared; people were running everywhere. Many buildings were on fire; smoke and tear gas filled the sky. We headed in a different direction but shots rang out in the intersection we were trying to move through. We got low in the car and safely made our way out of the area.

We drove to MoKaBe’s, one of the movement hangouts in the Shaw neighborhood. It was crazy there as well. The police had tear-gassed the café and people were walking around with the milky white residue of Maalox on their faces—Maalox, when mixed half and half with water, is the favored treatment for tear gas and pepper spray on the skin.

Folks were worn out from the emotional pain and relentless actions. I knew that Ferguson would be burning all night long. I also knew we had a plan to shut down intersections in Clayton first thing in the morning. I dropped Julia off at her home, headed back to where I was staying, set my alarm for 5 AM, and collapsed into bed.

Healing Racial Divides

Being compassionate and seeing ourselves in others is an important step toward liberation. In 1995, when I was working on the Justice for Janitors labor campaign in DC, racial tensions surfaced between the Latinx and African American workers, undermining our cohesion in the streets. We brought folks together to talk it all out. One of the African American janitors, Glenda, talked about being raised by a single mom in Anacostia, a poor Black area in DC. She talked about how there wasn’t enough food on the table, how there was no playground, how the police hassled folks in the streets. As she spoke, a Latinx woman, Maria, was crying. She told her story of growing up in San Salvador, the capital of El Salvador. She, too, was raised by a single mom because her father, a union leader, had been disappeared by the death squads. There was always a shortage of food, and the kids were afraid to go outside. Listening to this, Glenda was in tears as well, and the two women came together in a tender embrace. The solidarity and love between them pulled everyone else together, and that was the end of the racial tensions.

The Power of Facing Racism

On the one-year anniversary of Michael Brown’s death, one of the groups founded in Ferguson, the Deep Abiding Love Project, distributed a manual called Coming to Ferguson to activists arriving in St. Louis.17 The goal was to communicate that Ferguson wasn’t a movement to tap into once, feel good about yourself, then go home with a badge of honor. It was a movement dedicated to the hard, lifelong work of undoing racism and white supremacy. The manual encouraged newcomers to “show up and shut up”:

SHOW UP AND SHUT UP: Understand that your role in Ferguson is different than your role in your own community. Here, the only credential that matters is how many times you have shown up. Your role as an outsider is to be present, to really listen. Be flexible and learn to recognize the new forms leadership has taken in this movement, figure out how to listen to new voices without putting that burden on local organizers or giving unasked for counsel.18

The activists in Ferguson were super conscious of supremacy—race, gender, and class—snaking their way into grassroots groups. The privileging of the voices and ideas of white people and white men can be insidious and difficult to recognize, which is why it’s so important to be explicit and specific about how privilege shows itself. Personally, I’ve learned that I’m acting out of white superiority when I work with urgency or demand perfection, if I am patronizing, when I believe there’s only one right way to do something, or when I act or feel like a savior.

Without having done the hard work of learning, white folks are mostly unaware when they’re acting from a place of internalized superiority, and tend to deny it when it’s pointed out. This denial causes people to hide behind other common behaviors of internalized supremacy, like distancing, fragility, and arrogance.

The privileges and rewards of being white, male, straight, able-bodied, and Christian have been woven into the fabrics of our cultures and institutions since the country’s founding. The Naturalization Act written by the very first Congress in 1790 defined US citizenship as being available only to “free white people,” making the United States of America the first country on Earth to put the concept of “white” into law. For centuries, white men carried the privilege of laws that allowed them, and only them, to own property and land, while all men were socialized and given the power to subjugate women.

As such, white people and men became invested in the process of keeping things the way they are—but the way things are creates irrational fears about “others” and justifies complacency to injustice and the use of violence and oppression. These acts and traits of internalized superiority sap energy, create trauma, and deny the humanity of others as well as ourselves. The values of supremacy breed competition, control, individualism, greed, and the use and acceptance of brutality and force.

As taught by the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond, the flip side of this internalized superiority is the internalized inferiority experienced by people of color, which has created generations of traumatized people who pass that trauma to their children. Superiority and inferiority make us all sick. It’s just that white people, men, and rich people are comfortably sick.

Liberation is not a word I typically associate with white people, but undoing racism and superiority is liberating for people of all backgrounds. Funny enough, even the dictionary definitions of liberation, written by white people, carry hierarchy and white supremacy within them. One example is: “the act of setting someone free from imprisonment, slavery, or oppression; release.” We speak of “setting someone free” as if people cannot free themselves. We see liberation as the forceful undoing of some external imposition—and it can be, but true liberation comes from within, because it is our minds, as well as our bodies, that have been colonized and bound.

In the book My Grandmother’s Hands, therapist Resmaa Menakem writes about how the culture of white supremacy is so endemic to our environment that we’re all walking around traumatized because of it. This book was eye opening for me. Menakem proposes that white Americans suffer from the “secondary trauma” of having witnessed or been complicit in racial violence, going back generations to white Europeans who witnessed or inflicted unspeakable brutality on other white people.19 The colonists who came to this continent brought this violence with them as they waged a campaign of genocide against Indigenous peoples, then captured and enslaved Black and Brown people as well as poor white people, though the latter were freed of their indentured servitude. Menakem’s premise is that the racial tensions in our culture are literally hardwired into our bodies, creating symptoms of chronic fear and hypervigilance.

Racism infects every aspect of our society, and anti-racist work must be explicitly practiced within and between movements, as well as within ourselves, our families, and our communities. The work of undoing racism and all forms of supremacy is lifelong work, it is difficult work, and it is essential to creating the world we hope for. As the civil rights leader Bayard Rustin once wrote,

If we desire a society of peace, then we cannot achieve such a society through violence. If we desire a society without discrimination, then we must not discriminate against anyone in the process of building this society. If we desire a society that is democratic, then democracy must become a means as well as an end.20

Undoing these oppressive and violent belief systems requires consciousness and strategy that move beyond “issue work” and into the daily practices of noticing and changing beliefs and behaviors.

In the 1980s I was a co-coordinator at the Washington Peace Center in Washington, DC, an organization that had been composed primarily of white folks since its founding in the ’60s. In 1988 a new co-coordinator came on board, Mark Anderson, a smart, skilled organizer who called upon us to step out of our unconscious white privilege and address head-on the racial divides in Washington, DC. We participated in the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond’s Undoing Racism training, which forever changed my life. This was the beginning of a process in which we addressed racism personally and in the organization, leading to many changes, including the leadership of the board, the programs we organized, and how our services were offered. At one point six people of color joined the board at the same time, unlike the many organizations that bring in one person of color, which is both untenable and tokenizing.

Years later, in the fall of 2002, I was involved in organizing a new antiwar group initially called United for Peace. The older peace movement in the US espouses concepts of “peace” that often lack racial analysis and make invisible the inherent racism in US wars. Myself and others advocated to change the name to United for Peace and Justice—there is no peace without justice. Believe it or not, there was resistance, but we held firm.

As part of the anti-racist process at UFPJ, we included racism in our analysis of war, acknowledging that people of color must serve in disproportionate numbers as a way out of poverty and that most of the wars being waged are against brown-skinned people. We also made a conscious, deliberate effort to center the voices and leadership of people of color. Our steering committee was majority women, majority people of color, with 15 to 20 percent queer and youth representation. We got very explicit about the numbers, which can be extremely helpful. We also agreed that the leadership body had to have equal representation, fifty-fifty between local groups and national organizations. This intentional building of a diverse leadership body is a must if we are to undo racism.

One of our co-chairs, George Friday, grounded our mass assemblies in anti-racism work. She introduced me to the concept of strategic use of privilege, describing how the heavy lifting of reform must not be left to the peoples or communities most affected by injustice. So if homophobia is in the room, straight people must speak to the importance of LGBTQ rights; if there are young people in the room, elders must step back and make room for young voices; if sexism is playing out, the men must acknowledge and combat it; if folks with disabilities don’t have access, able-bodied people must fight for it; and if racism is alive, white folks must interrupt it and hold other white people accountable. I learned that the people with the most power and privilege have the greatest obligation to undo the injustice. George also teaches about the importance of working in community and building relationships as integral factors in combating racism and patriarchy, all of which requires work, time, and integrity. Strong relationships allow us to talk about the elephant in the room—oppression.

The monumental task of undoing white supremacy can feel daunting, with undefined goals and parameters. Like all oppressions, it is working at individual, institutional, and cultural levels. Yet there are very tangible injustices that can be fought against every day as members of our communities are taken to jail for petty crimes, evicted from their homes, or torn from their families by ICE. In response to the recent escalated threats to immigrant communities, Muslims, and Jewish people, folks are providing support along the border walls, showing up at airports, and building human perimeters of protection at spaces and events. Communities have formed rapid response networks to thwart and minimize harm by the Trump administration’s disturbing executive orders.

No matter who is in power, we need to develop an offensive political strategy that creates and tightens a web of restraint around the activities of the police and agencies like ICE that play out daily in many communities. We also need an offensive strategy to protect ourselves, our neighbors, and our communities from the growing white supremacist movement. Some ideas to protect ourselves and our communities include:

Educate yourself about systems of oppression, as well as about what’s happening in your own community. What is its history of race relations? What are the patterns and practices of local police? Which communities are being targeted? Who is already organizing for racial justice?

Develop authentic relationships and have real conversations with people who are different from you about the elephant in the room—systemic oppression.

Become mindful of your language. Use people-centered language. For example, instead of saying slave, say enslaved person, or instead of illegal alien, you could say undocumented immigrant.

Get together with your family, friends, neighbors, or co-workers to raise money for an Undoing Racism Training with the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond.

Show up at (or organize) local protests against police brutality, acts of oppressive violence, gun violence, and the mistreatment of immigrants or marginalized communities.

Support local organizations that provide legal defense work. Raise money for groups that are most affected by oppression. Start a community bail fund. Bail people of color out of jail.

Speak out when you hear or see racial bias in action, and share your strategies with your friends, on social media, or in a letter to the editor of your local paper.

Talk about your values and beliefs with friends, family, and neighbors. Be an antidote to the relentless right-wing propaganda campaigns that dehumanize people of color and “the left.”

Get groups of friends and family together and tap into community-wide rapid response networks that respond when activated by groups of color.

Set up safe houses.

Organize campaigns that disrupt business as usual for public officials; call for accountability for acts of violence, hate speech, and unjust ordinances.

Provide food, child care, or transportation to people of color who are organizing.

The uprising in Ferguson is a model for how community-based activism can lead to real changes and inspire community-led efforts elsewhere. The groundwork built in 2014 has given rise to movement forces and infrastructure, including the tactical use of social media platforms. I remember as recently as 2006 when the immigrants’ rights movement used the radio to organize that year’s Day Without Immigrants. Black Lives Matter was one of the first to use Twitter as an effective organizing tool to not only raise awareness but also let people know where protests are and what’s happening, with live updates, and DeRay Mckesson and Johnetta “Netta” Elzie developed a huge Twitter following about the uprising.21 Social media cannot replace on-the-ground relationships, but when used strategically, it can rapidly expand your base and advance your message. This is the sweet spot where social media enhances on-the-ground organizing—and vice versa—in a true synergy.

The Ferguson uprisings led to the emergence of the BlackOUT Collective, a Black-led direct-action trainers network led by Celeste Faison and Chinyere Tutashiada. Local organizers have elected progressive Black officials who will represent their interests. Multimedia artist and organizer Damon Davis, with Sabaah Folayan, went on to make an award-winning film, Whose Streets, and Taylor Payne went on to form The Yarn Mission, knitters for justice.22 Ferguson also led to The Artivists, a group created by my friend Elizabeth Vega, who saw the power of creative direct action and has not stopped since.23

And it was in Ferguson that Black Lives Matter, a movement that began online in 2013, really put boots on the ground. Patrisse Cullors, one of the three queer women who founded BLM, mobilized a group of six hundred to travel to Ferguson over Labor Day 2014. Soon local BLM chapters sprouted in communities all over the country. Over these years BLM has grown into a powerful network that continues to take action for transformative change. In 2015 the Movement for Black Lives emerged and became a political force developing a policy platform for the movement that is being used in communities across the country to bring about systemic change. This platform was backed by Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ), a white solidarity organization that grew fast after the murder of Michael Brown.

The Ferguson uprising crystalized the call and uplifted the tactic of shutting things down. Their chant—“If We Don’t Get It, Shut It Down”—was repeated in hundreds of cities across this country. The tactics we used included shutting down highways, shutting down streets and intersections, shutting down offices, and even shutting down the police station. People were fed up and were not going to take it anymore, instead taking action to creatively disrupt business as usual using their bodies, hearts, and minds, each time repeating the powerful words of Assata Shakur: “We have a duty to fight for our freedom. We have a duty to win. We must love and support one another. We have nothing to lose but our chains.” One cannot underestimate the power of such actions. When we lay down our fears and act from our hearts, there is really nothing that can be done to stop us.

The uprising in Ferguson was loving and fierce. Building on the bravery of the youth and the wisdom of the elders, a new path was laid forward. We have not overcome or undone racism, but Michael Brown’s death made it a national discussion. Mass incarceration is being challenged; police violence is being challenged. We have finally seen convictions of police who have murdered. More people are recognizing white supremacy and are joining the fight against it by taking action. We have not reached the promised land, but this new generation is teaching us that we must take a stand, we must shut things down, we must rise up, and we must fight and heal together.