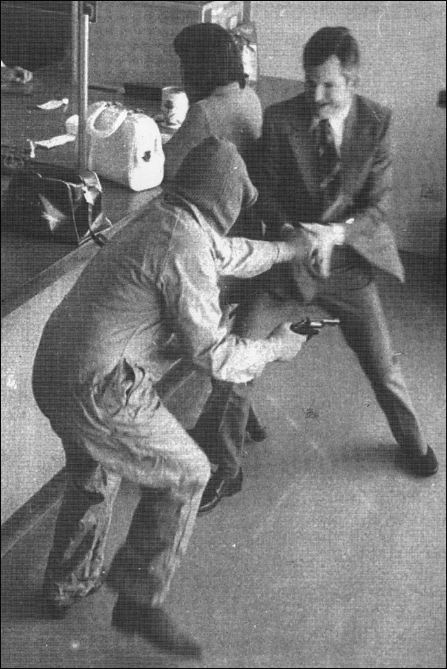

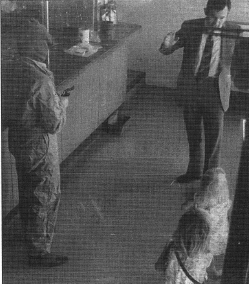

Robber and sex offender Maurice Marion grabs for a bank manager’s revolver.

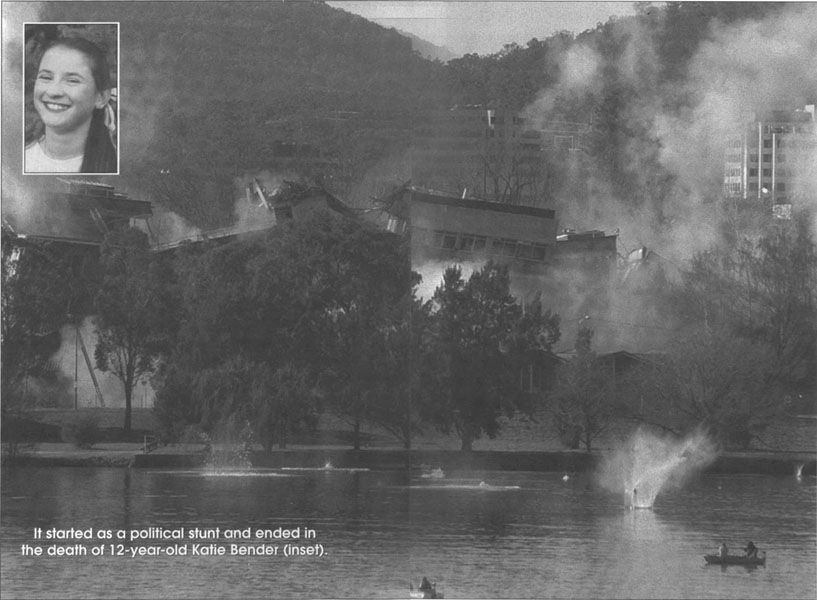

THE little white cross stands guard over a sweep of green grass running down to the water’s edge. Even in the serene sunlight of late afternoon, the cross looks brave and lonely and disconcertingly out of place. Step closer and it brings a lump to a stranger’s throat. Here, inside a square about a metre wide and long, are reminders that a young girl died a violent death in this peaceful park beside Lake Burley Griffin.

The square that frames the cross is neatly edged in white-painted timber, and filled with tan bark and heartbreak. A bunch of fading fabric flowers is tied to the cross. At its base is a tattered white teddy bear and a brown toy platypus. Wrapped around it is a tiny crucifix on a string of beads. Beside it, a flower pot with a pale pink bow.

This is a quiet spot. No one lives or works within hundreds of metres, but in two years no vandal had touched the memorial. Perhaps that is because the story of the girl killed here on 13 July 1997 has touched so many people in the city where she lived and died. Her name was Katie Bender.

VICTOR Muscat couldn’t explain, afterwards, why he sensed danger that day. Perhaps because he was standing on the back of a parked truck, higher than the huge crowd around him, and subconsciously felt exposed. Or, being older than those with him, he felt a twinge of responsibility.

He told a friend’s son to get ready to take cover. ‘I said: “Brock, move over to the edge of the truck, just in case something goes wrong. It gives us a chance to get down behind it.”

‘His father had a bit of a chuckle and he said, “Vic … these blokes are experts, nothing should go wrong.”

‘When I saw the stuff landing in the water I turned to Brock and I said, “Get down!” and I grabbed (him) by the seat of the pants and pulled him off the side of the truck. He landed on the ground and I jumped down and crouched …’

It was then he heard ‘something coming’. A ‘swooshing’, he was to tell a grim-faced policeman four days later, ‘like a big pelican flapping its wings’.

In the crowd were a few old men who remembered that sound from distant battlefields: it was the hiss of shrapnel slicing through the air.

Torn branches fell from the poplar trees. A jagged piece of steel ripped through the bonnet and wheel arch of a car, bounced off the tyre and spun away behind the crowd. Miraculously, it didn’t hit anyone. But there were other pieces, and other people.

Fifty metres away, someone yelled, ‘We’ve got a woman, we’ve got a woman here.’ Then another voice, shrill with horror: ‘Someone got hit just there.’ Then screams and sobs.

It was just before 1.30pm on 13 July, 1997. The day political pressure, bureaucratic bungling and an explosive contractor’s ignorance turned a peaceful Canberra park into a war zone.

The wings Victor Muscat heard belonged to the angel of death.

BENEATH its capital city trappings, Canberra is still a big country town, especially after the last flight out on Friday night. On weekends, there’s not much to do. Which explains, partly, why 100,000 people – almost a third of the population – turned out to watch the old Royal Canberra Hospital destroyed with high explosive.

Such a spectacle is somewhere between a picnic and a public hanging – tempered, in this case, with sentiment. Thousands of locals had been born in ‘Royal Canberra’, and wanted to see its exit.

It seemed a promoter’s dream: a perfect Canberra winter day, with brilliant sunshine, blue skies and clear air making Lake Burley Griffin a dramatic backdrop for an event cleverly hyped through a willing local media.

One FM radio station, MIX 106.3, had the green light from the authorities to milk the demolition for publicity. Not only had the station’s program manager been invited to a meeting to decide when to stage the implosion, but he’d been allowed to suggest the switch from a weekday to a Sunday so more spectators could be there. No-one opposed it.

Opponents – known or potential – of the implosion were well out of the decision-making loop. Some of the sharpest minds for hire had seen to that.

So completely had the demolition become a media event that Canberra newspapers ran prominent stories telling how to get to the best vantage points. The Lions Club devised a scheme to sell souvenir hospital bricks at $2 each to raise money. And MIX 106.3 ran a competition for listeners: First prize, pushing the plunger to blow up the hospital.

The winner, a woman called Sue George, joined a small group on top of the old maternity wing of the hospital that Sunday, well before 1pm, the scheduled time for imploding the main wing and chimney stack. Meanwhile, an official party had gathered on the top floor of Rydges Hotel overlooking the lake for a celebratory lunch.

As the huge crowd gathered across the water, Sue George waited for the signal to push the handle that was supposed to ignite a series of explosions within a split-second of each other. This, theoretically, would blow out key supports so the building would crumble inside its own ‘footprint’, like a house of cards. Not that anyone who saw the problems behind the scenes would have been as trusting as the thousands who’d come to watch.

The good weather brought people who might otherwise not have bothered. Among them was the Bender family.

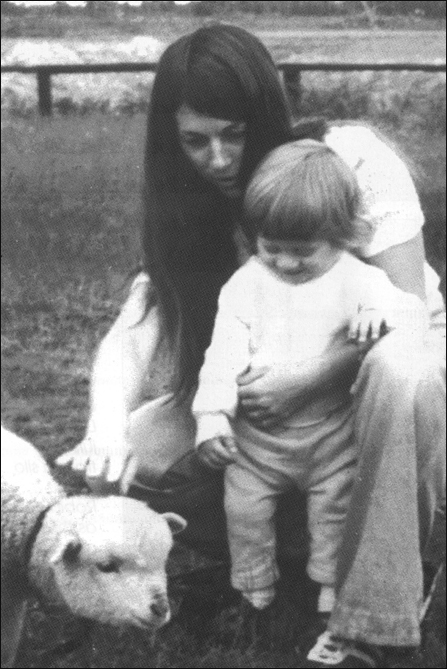

MATO and Zora Bender had come to Canberra soon after migrating from Croatia in the 1970s. Their four children had been born there. First, Anna, who was twenty in 1997; then Maria, nineteen; David, seventeen, and finally, Katie, just twelve.

Mato was a janitor at a local school. He and his wife were devout Catholics and members of one of Canberra’s two Croatian clubs, where Katie was a folk dancer with other youngsters. The night before, the family had gone to the club to watch her dance. And on this Sunday they’d been, as usual, to 11am mass at St Patrick’s Church.

They were on the way home to the cream brick house that Mato had built in Rosebery Street, Fisher, a suburb south of central Canberra, when they decided to stop and watch the implosion. David had heard about it on the radio and wanted to see the show. They brought a blanket from the car, walked through the gathering crowd, and picked a spot in Lennox Gardens, seventeen metres from the paved shoreline of the man-made lake.

The one o’clock deadline came and went. About five minutes later, there was a flurry of bangs, smoke and sparks – but it was only a fireworks show intended to precede the implosion by a few seconds. Nothing happened.

What the disappointed crowd didn’t know was that the fireworks display – mounted without a permit and certainly ill-advised – probably harmed the wiring that connected about 500kg of high explosive split between the 260 steel and concrete columns holding up the hospital’s six floors.

The shot firer, under pressure that had been mounting on him for weeks, worked feverishly to fix the fault. Unfortunately, he succeeded.

It was a little after 1.25pm when Sue George finally got the thumbs up. She plunged the handle again. Smoke and a fireball belched from the building, the result of drums of diesel set up, like the fireworks, purely for effect. Concrete rubble sprayed from the building, pocking the lake with huge splashes, some among the dozens of boats that bobbed beyond the 200 metre ‘safety’ zone enforced by the police.

Lethal as it could have been, the rubble wasn’t the worst danger. It was the pieces of steel flying above the water towards the opposite bank at speeds later calculated at 150 metres a second, like an artillery bombardment. Or, as the shaken explosives contractor later admitted to police, ‘like putting a shotgun among a group of pigeons’.

KATIE Bender had been sitting on the blanket as she waited. She stood up when one of her sisters suggested she would get a better view that way.

It’s not true to say that no-one saw the missile coming. Some did. All they could remember, later, was that it was very fast. Too fast for Katie to dodge, even if she’d seen it.

The indications are that she didn’t, and that is a shred of comfort for those who loved her: they know she didn’t suffer even a split-second of fear or pain. The shrapnel covered the 430 metres between the hospital and Katie’s forehead in less time than it takes to read this sentence.

The impact was so great, and death so instantaneous, that she fell to the ground with one hand still in her pocket, her face as composed and peaceful as if she had fallen asleep.

There has been no peace for those who saw. Peter Jermyn, a tree surgeon, was standing several metres behind the Benders with his family when he saw something land on the grass. For a moment, he thought it was a wig. It was Katie Bender’s scalp. A piece of her skull hit Jermyn’s six-year-old daughter in the face.

Jermyn ran to where Zora Bender was clasping her dead child in a scene that seared the memory of those who were there. He saw emergency service people put a chair and a sleeping bag over a piece of skull on the grass.

Constable Stuart Howse had heard the buzz of shrapnel above the crackle of the radio in his police motorcycle helmet. Then he heard screaming and sobs. He rode his machine through the crowd, emergency lights and siren sounding to force a path. Two firemen got to the body at the time.

‘As soon as I got off the bike and walked around to where the victim’s head was, I knew exactly what had happened,’ the policeman was to say in a hushed courtroom later. ‘And at the point I spoke to two fire officers and said to continue CPR for basically the crowd’s perception of what was going on, with kids around …’

On the ground behind the body was a triangular piece of steel the size of a dinner plate, its jagged edges still wet with blood.

Across the lake, the huge hospital chimney stack had fallen outwards towards the water – not the direction it was supposed to. It had all gone terribly wrong.

SUCCESS has many fathers, failure is an orphan. As soon as the ambulance sirens began to wail no-one wanted to be connected with the event. Especially the ACT Government, which did an astonishing about-face.

The Chief Minister, Kate Carnell, had angled for the implosion for almost two years. The advisers and bureaucrats who had pulled so many strings to stage the implosion mounted a hasty rearguard action to shield Carnell – and themselves – from the fallout. But it was too big a job, even for experts. It went back a long way.

Long before Katie Bender was born, the man who planned modern Canberra, Walter Burley Griffin, had envisaged not just the lake that bears his name but a little bit of Venice on the Monaro. He wanted canals and houses on the Kingston foreshore. Instead, there were paddocks, an old power station and the Commonwealth printing works.

Successive federal and, later, territory governments were lobbied to create a showpiece waterfront suburb, without success. It was clear the only way the Kingston foreshore would be developed was if the ACT Government took over the site from the Commonwealth.

The opening came in 1995, when the Keating Government decided to build the proposed National Museum of Australia closer to the city rather than at an existing site at Yarramundi, which would have been more expensive because it was further from services.

Carnell saw her chance to swap the Acton Peninsula, owned by the territory for the Commonwealth land at Kingston. The snag was that the old Royal Canberra Hospital, closed a few years earlier, was on the peninsula. But Carnell and her advisers were confident they could fix that. Despite the protests of those who wanted to refurbish the hospital building for other uses, and those who favored the Yarramundi site for the museum, Carnell and then Prime Minister Paul Keating struck the land swap agreement in March 1995.

Opposition stayed strong. A protest group fought demolition of the old hospital buildings. Some critics said the Acton peninsula was too small for the proposed museum and pushed for the original Yarramundi site.

The Federal Government set up a committee to report on the issue – under the chairmanship of one Jim Service, a prominent banker and builder. Later, Carnell was to appoint a former head of her department, Jeff Townsend, to chair the Kingston Foreshore Authority.

Neither committee was expected to surprise the ACT Government with its recommendations. What the Chief Minister wanted, it seemed, she was going to get.

And if what she wanted wasn’t clear before late 1995, it was very clear afterwards. On 16 and 17 December, ACT parliamentary Liberal Party members, their advisers and senior public servants gathered at the Eaglehawk Resort motel on Canberra’s outskirts for a strategy weekend irreverently dubbed a ‘Liberal Love-In’.

The Carnell administration’s can-do attitude marked the hit list of sixty ‘strategic issues’ discussed that weekend to bolster the party’s electoral appeal.

Brainwave number thirty-one on the minutes was headed ‘Bomb the Acton Peninsula buildings’. It went on to say: ‘The buildings currently act as a living reminder of the closure of the RCH (Royal Canberra Hospital) and the sentimental baggage which that carries.’

The minutes, subsequently leaked by Liberals worried by their leader’s gung-ho approach, continued: ‘The buildings should be bombed as soon as possible and the proposed museum be allowed to get under way.’ The word ‘bombed’ was later crossed out and replaced with a blander word.

As the leaking of the list showed, Carnell’s critics included some on her own side – including her deputy Gary Humphries, who was against the Acton peninsula land swap. But Carnell had surrounded herself with advisers – many of them hired from Sydney – who did not oppose her tendency to take shortcuts to get what she wanted. Most senior of these advisers was John Walker, a former NSW political strategist who had played a part in the Sydney 2000 Olympics bid – a curriculum vitae probably considered more desirable in the first flush of Sydney’s triumph over Beijing than after the scandals of four years later.

Robber and sex offender Maurice Marion grabs for a bank manager’s revolver.

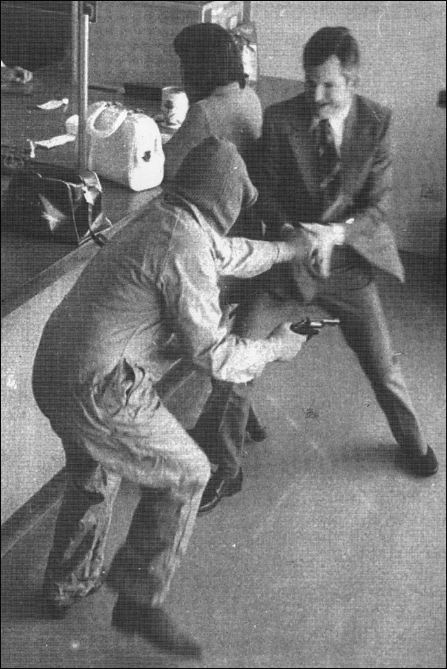

A young woman cowers in terror as Marion fires a shot with his right hand while grabbing the manager’s gun with his left.

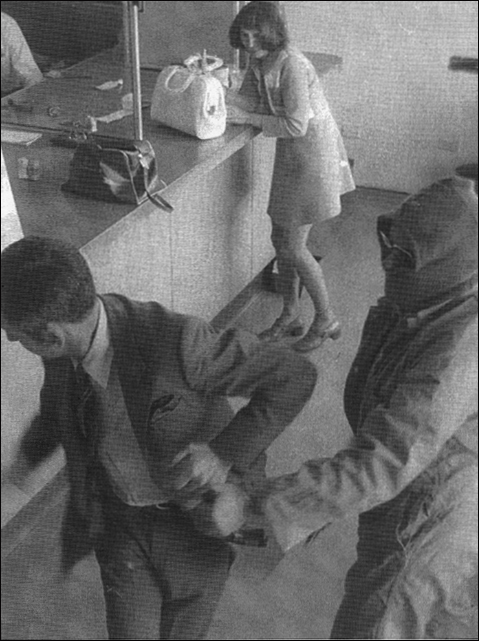

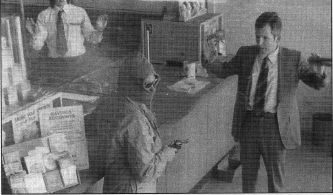

The manager surrenders, puts his hands up and warns two children before Marion escapes.

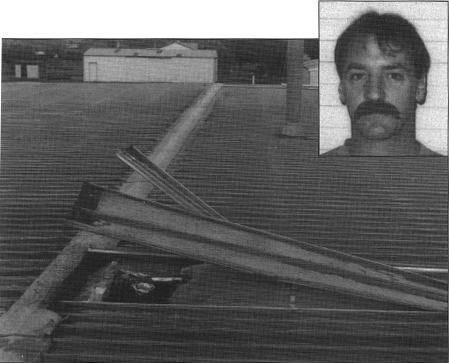

Missing presumed murdered, since 1992 … Prue Bird. Her grandmother’s de facto Paul Kurt Hetzel (inset).

The scene outside Melbourne’s Russell Street police station minutes after the car bomb exploded in 1986, killing a policewoman

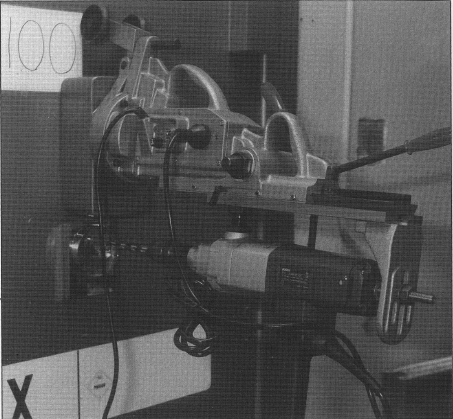

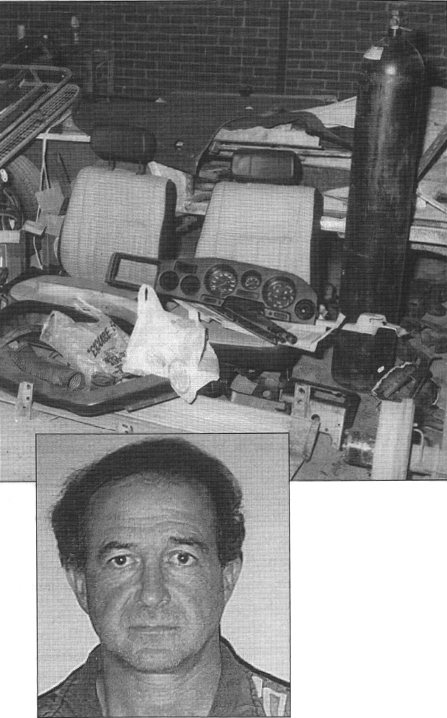

Service is our business … Telstra disguises used by would-be amphetamine thieves

George Lipp

Paul Elliott.

Brian Zerna. Their point of entry (inset)

Magnetic drill ready to go

In the safe door and semiautomatic pistol

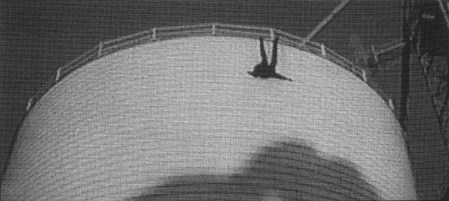

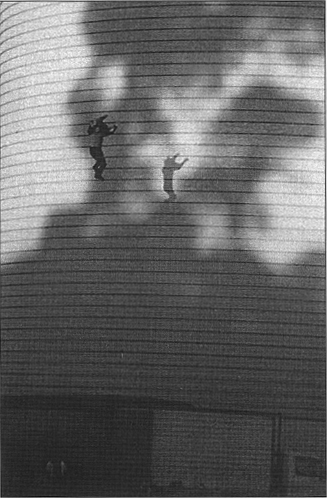

Stuntman Collin Dragsbaek … didn’t break a bone until the day he died.

The fatal fall … Collin Dragsbaek jumps from a silo at Robinvale as the cameras roll.

Easey Street victim Suzanne Armstrong and son Gregory. Her friend Susan Bartlett (inset) was also killed.

‘Sun’ crime reporter Tony Wilson reaches for his Dunhill cigarettes outside 147 Easey Street Collingwood.

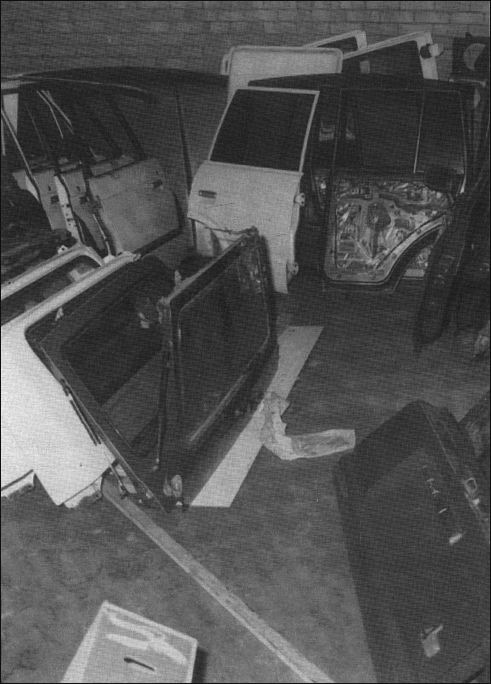

Ever wondered what happens to stolen cars? They are cannibalised by people like Rick Renzella – race rigger, punter, car dealer and dopey dope grower.

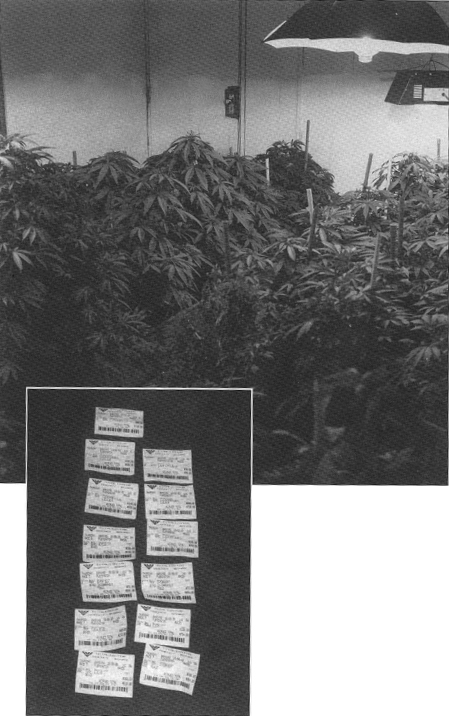

Up in smoke … police photographs of Rick Renzella’s cannabis crop and thirteen betting tickets. Only one was a winner.

Walker, notorious for his abrasive style with subordinates, became head of Carnell’s department. As a politician, Kate Carnell retained a small business mind-set. She liked to get things done quickly. Her critics – there were several – accused her of shooting first, asking questions later. But her greatest weakness, they said, was her taste for getting her picture in the newspapers.

Carnell, daughter of a Queensland builder, had come to Canberra as the wife of a senior public servant, and later ran her own pharmacy in the well-heeled suburb of Red Hill. The marriage didn’t last, but the ambitious pharmacist flourished, using her latent instinct for self-promotion to make a splash in the small puddle of ACT politics, in many ways an overgrown city council.

Carnell, dubbed by a former political colleague as ‘a poor man’s Ros Kelly’, was personally attractive but publicly accident prone. She had a touch of fellow Queenslander Pauline Hanson’s tendency to polarise voters with her blend of populism and personal appeal, and relied heavily on advisers who sometimes became close friends, though not always permanent ones.

She paid little heed, notes the former colleague, to the separation of powers of the judiciary, the administration and the executive that underpins the Westminster system.

She used the media to advantage, but sometimes her eagerness to count coups for Canberra earned a rebuke. In September 1996, for instance, the Canberra Times – not renowned for its criticism of Carnell – ran a scathing editorial about her hasty decision to build a world-class indoor soccer stadium to stage a championship tournament.

‘Residents putting up a garage are required to engage in more community consultation than was done before the stadium was approved and construction begun …’ the editorial read.

This tendency to jump the gun hinted at what lay ahead.

ANY investigation of what caused the debacle that killed Katie Bender leads to a simple question: Why implosion?

The Eaglehawk Resort conference of December 1995, was not the first time implosion had been mooted.

Months earlier, in July, the Construction and Maintenance Management Service – the government body later renamed Totalcare – had commissioned a feasibility study on demolishing the hospital.

Ron Deeble, of Richard Glenn and Associates, wrote the report. He cautiously conceded that implosion was one way (though not the only way) to demolish the hospital, but added a warning – if an implosion was to occur, it should be at a quiet time and known only to those who needed to know.

By the time the report had filtered through sieves of political self-interest and bureaucratic apathy for almost two years, only one word of it remained: Implosion. Everything else was jettisoned.

Why that happened is a damning example of how government works – or doesn’t – when political expediency rules in a Yes Minister world of offices and officials, minutes and memorandums. It is the story of a political farce that turned into a tragedy.

Backtracking to trace those responsible isn’t easy. That has been proved in about one hundred hearing days at the inquest into Katie Bender’s death, which still hasn’t produced a finding many months later on.

Sharp players of the government game leave a faint trail, if any. The levers and strings pulled to make some things happen – and block others – are mostly invisible. Unless careless, complacent or naive, politicians and public servants try not to write down anything that might embarrass them later. Covering tracks – and backs – is an art form.

As any ministerial office staffer can testify, the tools of trade are the telephone call, the unofficial meeting, the broad hint, the veiled threat and – if necessary – the handwritten note that can be attached briefly to an official document, file or letter, then vanish.

The full story of the ‘strategies’ leading to the implosion is known only to a few, who are saying nothing – or as little as the law requires them to.

The slow-burning fuse that led to Katie Bender’s death had many strands, but was lit by an urge to distract the public with the ancient political ruse of ‘bread and circuses’ in the lead-up to the 1998 ACT election.

Kate Carnell knew her Government had a problem: it represented self-government that most people didn’t want which had closed a hospital most people did want because it could no longer afford it. She hoped that one symbolic act would kill two birds with one stone: win her the glory of getting the Kingston foreshore developed, and end the hospital controversy. Instead, it killed a little girl.

THE facts speak for themselves. In early January 1997, ostensibly before any demolition method is formally agreed on by experts, Kate Carnell publicly says the hospital will be imploded.

In February 1997, Carnell’s office contacts Totalcare, the Government agency responsible for handling tenders, to press for an implosion. Again, this pre-empts expert opinion about how to wreck the building.

When tenders are called, well-known contractors with flawless records on difficult jobs are passed over – including one who demolished the former ASIO building in St Kilda Road in Melbourne in just thirty days. International implosion experts are not consulted.

The demolition contractor awarded the job seems to accept implosion as a foregone condition of the contract, despite the feasibility of conventional demolition. He sub-contracts the explosives work to one Rod McCracken, a shot firer with a long but chequered career with explosives. Checks would have revealed claims that McCracken had left a demolition job in a NSW cement works in 1994 after serious doubts about his work.

McCracken foolishly agrees to meet an unrealistic and artificial deadline when a request is relayed from the Chief Minister’s office for ‘a big bang on the Queen’s Birthday’ – 9 June 1997. Carnell arranges to pay a child-care centre located in the hospital building more than $250,000 to move out quickly to allow demolition to go ahead – despite the fact the Commonwealth has no intention of using the site for the proposed museum for at least a year.

McCracken is told, wrongly, no architect’s plans are available. He belatedly finds that the hospital – designed in wartime to withstand bombing – has huge steel columns inside its concrete supports, of a strength he’s never handled before.

He believes he can’t get the correct steel-cutting charges in time to meet the June deadline, so decides to pre-cut the steel with blowtorches and use a blasting explosive called Riogel, designed to shatter rock in quarries. He hasn’t used Riogel before. Instead of admitting the unexpected problems he faces, McCracken says he can meet the June deadline. His guesswork about the amount of explosive needed is so arbitrary that after telling the Canberra Times just three days before the implosion that he’d almost doubled his explosive charges to 225 kilograms, he more than doubles it again in the last hours.

No permits are issued for the fireworks or drums of fuel placed inside the building to create extra smoke and flame, purely as a spectacle. Aviation rules require a warning to be given to aircraft before an explosion. This is not done – with potentially fatal results for a light aircraft flying overhead at the time of the detonation.

After being told that 2000 square metres of the chain mesh normally used to secure blasting sites to contain ‘fly’ (shrapnel) will cost $4000, McCracken refuses to accept delivery of it. His laborers stack sandbags around three sides of the steel columns – but not on the side facing the lake. A rubble ‘bund’ wall to stop ‘fly’ is built – but it is not high enough and does not extend right around the site.

A two hundred metre safety zone is set, apparently on the optimistic theory that the implosion will drop the building inside its own ‘footprint’ without causing any ‘fly’ beyond fifty metres. Over the border, a few kilometres away, this would be a gross breach of NSW Workcover rules, which stipulate a five hundred metre safety zone for explosives operators – and one thousand metres for the public.

An engineer called Russell Wade later gives evidence that only days before the implosion he warned a Totalcare executive, Mike Sullivan, that military explosives operations involving metal require a one thousand metre ‘stand off’. Sullivan is to deny this in court but, like some other public servants, refuses to answer other questions on legal advice.

ON the night of the implosion Kate Carnell visited the Bender family, and she attended the funeral service at St Patrick’s the following week. At the same time, she righteously called on the ACT opposition leader, Wayne Berry, to let the ACT Coroner get on with his investigation and to stop trying to make political mileage out of the tragedy.

Even some of Carnell’s own political allies thought this a bit rich. It was no coincidence that one of her senior ministers, Trevor Kaine, later resigned from the Liberal Party and set up the United Canberra Party. It is surprising that Kaine was not called to give evidence.

The Benders believed their interests would be looked after. But, strangely, despite Carnell’s bluster about letting the coroner get on with it, the inquest did not begin until March, 1998 … the month after the election, which her Government won before any dirty linen could be aired in the coroner’s court.

The inquest was the first big inquiry run by new magistrate, Shane Madden. Given that, the appointment of counsel assisting him, Ian Nash, was an interesting choice. Nash is known as a fine family and administration lawyer who gets a lot of Government work, but he had little prosecuting experience in criminal matters.

While every political and Public Service figure was legally represented at huge expense to the public purse, the Benders had to rely on a legal aid system not geared to pay a suitably skilled advocate in a long and complex hearing.

Their plight won the sympathy of a prominent Canberra civil rights lawyer, Bernard Collaery – who, besides other achievements, had been Attorney-General in the first ACT Government, and so had a penetrating insight into the system that had failed the Benders so badly.

In Collaery’s view, the system had failed to prevent, through commonsense safeguards, a preventable accident. Then it failed to make amends. He represented the family as a matter of principle, at considerable cost to his firm.

The inquest was to hear hundreds of hours of evidence from dozens of witnesses. The last of them, perhaps, should have been called first. His name was Mark Loizeaux, a principal of an American family firm that has done thousands of implosions in the past fifty years.

Loizeaux is eloquent in and out of the witness box. But when contacted by the authors in his hometown of Phoenix, Maryland, he said he wanted to avoid saying that his evidence had made the Australian contractors ‘look stupid’.

Loizeaux, 51, flies all over the world to blow up buildings. When the author spoke to him he had just returned to his headquarters in Maryland after an emergency in Ohio, and was about to begin a job in India.

He said he sympathised with the Australian shot firer Rod McCracken’s plight, but the Canberra hospital demolition was not done the way his company would do it. Using the blasting explosive Riogel was ‘not well-advised – in fact, ill-advised.’

Lineal shape charges made to cut steel have been available in the United States since the late 1960s, and such charges would require less than a tenth the amount of explosive McCracken used on the hospital, he says.

‘We could have shipped it to Australia in two months – or flown it over within two weeks,’ he said.

He points out that the explosive is far more expensive by weight than Riogel, and that sending it on a dedicated flight would add up to $75,000 to its cost: the inference is that the extra cost might have dictated which explosive was chosen in Canberra. ‘Mr McCracken is a nice guy who is proud of his track record – maybe too proud to admit he had no experience in demolishing this sort of building. Pressure was put on him, and he’s not the type to tell someone to bugger off, so he tried to do it too fast. No-one did their homework, and there was a series of unfortunate incidents which resulted in the death of the young lady.’

Loizeaux said he believed he had ‘crystallised a lot of cloudy questions’ for the Coroner in the witness box, and afterwards.

‘I spoke to him in private after giving evidence. I said to him, “You’re in the capital territory with a lot of heavy-duty politicians and power players, you are in a bit of a box, aren’t you, Your Worship?”

‘He looked me in the eye and in about three sentences he made it clear he wants the truth to come out. I don’t think he’ll stand for a whitewash.’

Neither will the Benders, promises Bernard Collaery, who made a withering final submission to the coroner.

During the inquest, which ran more than a year, Mato Bender lost his janitor’s job at a Catholic school because he wanted to attend the hearings. He and his wife attended every day, except when graphic medical evidence was led about the terrible injuries inflicted on their daughter. They were there the morning Kate Carnell’s expensive barrister sought leave for the safely re-elected Chief Minister not to attend next day because of ostensibly pressing official engagements.

Leave was granted. Next day the woman Collaery stonily calls ‘Madame Stunt’ went parachuting to promote a charity fund raiser. It was, from her view, a great success.

She got her picture in the local papers.