MANAGING an important monastery required a team of senior departmental managers, professional aides and large numbers of servants.

Most monasteries were ruled by an abbot (Latin abbas: father) who was ultimately responsible for its household and financial affairs and to whom the monks owed obedience. He was assisted by a range of office holders called obedientiaries including a deputy (the prior), the novicemaster, the cellarer who was in charge of supplies, the chamberlain who looked after domestic matters, the sacrist who was responsible for the upkeep of the church, the precentor who directed the church services, the infirmarer who cared for the sick, and the almoner who administered the charitable side of the monastery’s work. In addition, senior monks known as roundsmen or circatores patrolled the complex ensuring that nobody was misbehaving or neglecting the Rule. The precise number, titles and duties of obedientaries varied from monastery to monastery. At Bury St Edmunds Abbey (Benedictine: Suffolk) there were four priors. At Durham Cathedral Priory (Benedictine: Durham) and Canterbury Cathedral Priory there were twenty-five major officials, some with subordinates. It is estimated that by the end of the Middle Ages as many as two thirds of monks in a typical monastery held office as obedientaries or as their deputies. Some monks received practical training in administrative skills, including bookkeeping. In many instances such officials were often excused part of their choir duties and eventually lived separately from ordinary ‘choir monks’.

Effigy of Abbot Parker (d. 1539), the last Abbot of Gloucester Abbey (Benedictine: now Gloucester Cathedral).

Cistercian abbeys were organised along broadly similar lines to the Benedictine monasteries, except that the porter of a Cistercian abbey would be responsible for distributing alms to the poor and the post of almoner did not exist.

Embroidered cope with the letters ‘WHY’ and a church; the rebus of William Whitchurch, Abbot of Hailes Abbey, 1464–79 (Cistercian: Gloucestershire). The cope is now in the parish church of St Michael, Buckland (Gloucestershire).

In some instances monasteries were ruled by a prior rather than an abbot. This happened when monasteries were ‘cells’ of, or subordinate to, more important abbeys, or in monasteries attached to cathedrals where the bishop was nominally in charge.

Many abbots (or priors) commissioned major building programmes and lavish works of art for their monasteries. The Cistercians have been called the missionaries of French Gothic architecture in northern England while elaborate fan vaulting was pioneered by the Benedictines at Gloucester Abbey (see page 16). Some abbots ‘signed’ the works of art they commissioned with their initials.

Monasteries depended on their income from tithes, rents, donations, services and traded goods. Monks were highly protective of these ‘rights’ and clashes with other landowners, tenants and townspeople were common. For example, on several occasions in the late fifteenth century, monks at Chester Abbey (Benedictine: now Chester Cathedral) were indicted in the mayor’s court for attacks on local citizens and in 1480 Abbot Richard Oldham and twelve others, of whom at least half can be identified as monks, were bound over to keep the peace with a large body of tradesmen. Not all monasteries were well managed: some abbots were weak and lax; a few possibly corrupt. Debt was a common problem; the description of a twelfth-century abbot at Bury St Edmunds – ‘pious and kindly, strict and good, but in the business of this world neither good nor wise’ – could have applied to many others.

Fragment of oak screen dated 1536 with the initials ‘A. S.’ (Adam of Sedbar or Sedbergh, Abbot of Jervaulx Abbey (Cistercian: Yorkshire) 1533–7. The screen is now in the parish church of St Andrew, Aysgarth (Yorkshire). Adam was executed in 1537.

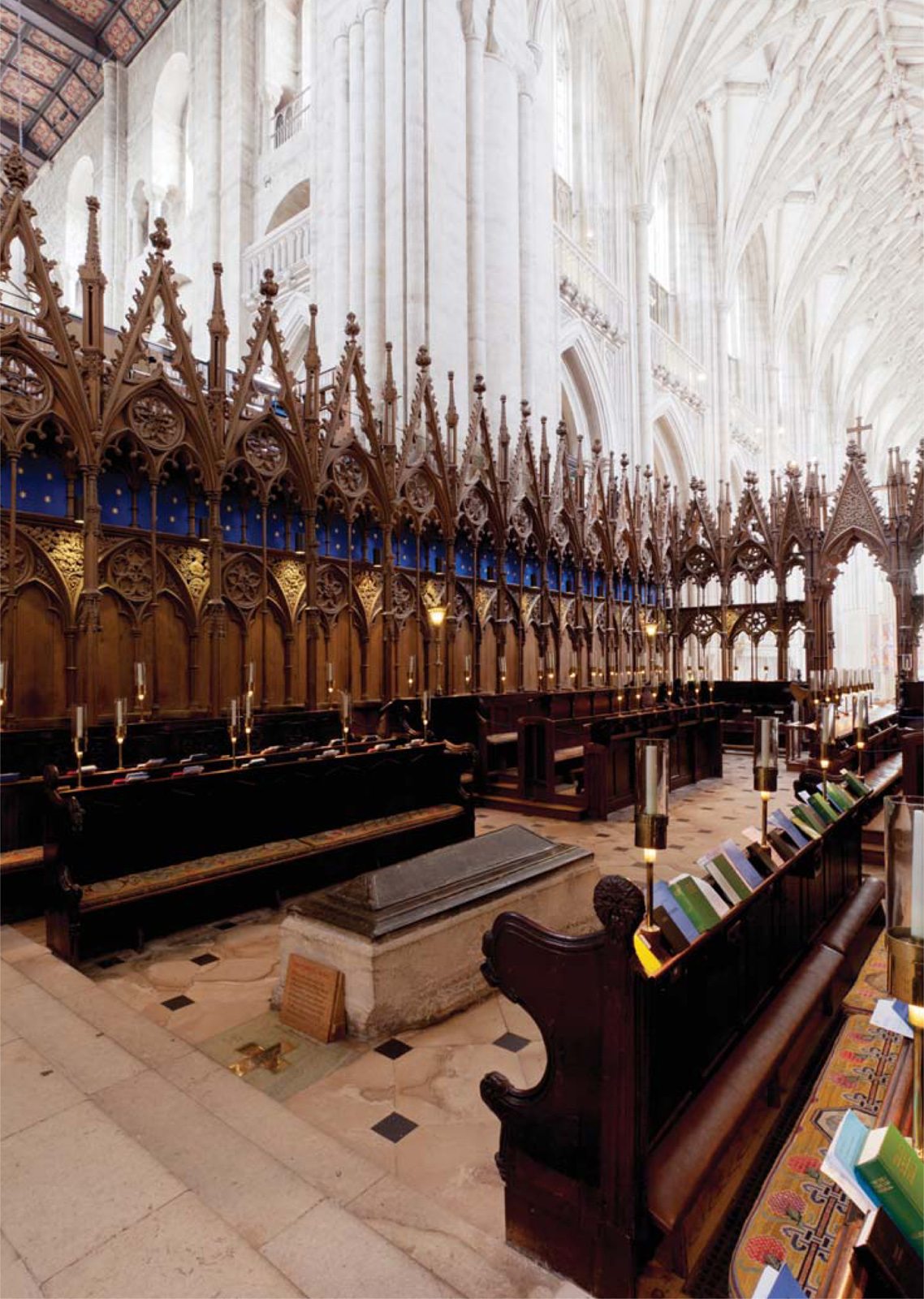

The early fourteenth-century monastic choir stalls at Winchester Cathedral Priory (Benedictine: Winchester, Hampshire).