APART FROM EATING, sleeping, washing, and short spells of private relaxation, the core of a monk’s life was a daily routine of liturgical devotion, interspersed with periods set aside for spiritual reading and manual work designed to prevent idleness and distractions. St Benedict called these periods opus Dei (God’s work), lectio divina (religious reading/study) and labora (labour/work).

By the beginning of the twelfth century each of the Four Orders divided their time between opus Dei, lectio and labora in different ways. Most monks spent a high proportion of their daytime hours in cycles of prayer, readings from the Bible and recitations from the Book of Psalms (Psalter), a collection of songs of thanksgiving and praise, and pleas for help from God. These cycles consisted of seven daytime services known as the Canonical Hours or Offices, each held a couple of hours apart and inspired by Psalm 119:164, Seven times a day do I praise thee. The first service began at daybreak with Lauds, followed by Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline at sunset. An eighth office of Vigils was celebrated at night. Over the course of the Middle Ages some of these services were known by different names. Lauds was once called Matins and what was then called Nocturns or Vigils is now known as Matins. In the late fifteenth century Matins and Lauds were together referred to as Vigils.

As a monk’s day was regulated by the sun, beginning at dawn and finishing at sunset, the timing of these services differed according to the seasons of the year. Before the invention of mechanical clocks in the thirteenth century, the time-tabling of services relied on water clocks and astronomy for accuracy. In keeping with their solitary life the Carthusians only came together in the church for Vigils, Lauds and Vespers, the remaining offices being recited in their individual cells.

Services were sung in an enclosed area at the eastern end of the church known as the Choir (alternative spelling: Quire), directly west of the high altar (presbytery) and separated from the nave by a solid screen, known as the pulpitum, which provided privacy and protection from draughts. Monks entered the church in procession from the east alley of the cloister in order of seniority, which was calculated by their length of service or rank rather than by age.

| CISTERCIAN TIMETABLE (WINTER) | |

| 2.30 a.m. | Rise |

| 3.30 a.m. | Vigils |

| 6.00 a.m. | Lauds |

| Prime | |

| Reading | |

| 8.00 a.m. | Terce |

| Mass | |

| Chapter-house meeting | |

| Work | |

| Noon | Sext |

| Mass | |

| 1.30 p.m. | None |

| Dinner | |

| Work | |

| 4.15 p.m. | Vespers |

| Reading | |

| 6.15 | Compline |

| 6.30 | Bed time |

Effigy of Hugh le Despenser (d. 1348), Tewkesbury Abbey (Benedictine: Gloucestershire). The Despenser family were the founders of the Abbey.

Monks were expected to take these services seriously, avoiding lateness or singing too fast. Early Cistercians particularly disapproved of ‘swelling and swooping’ voices, which ‘mocked’ the gravity of worship. While these misdemeanours were easy to recognise and punish, policing stray thoughts was harder, hence stories like that told by Abbot Robert of Newminster Abbey (Cistercian: Northumberland) who claimed to see the devil lurking outside the choir armed with his three-pronged fork ready to snatch monks who were not wholly focused on their religious duties.

From the twelfth century onwards the Choir area was equipped with hinged seats for the comfort of the monks during these services. Fourteenth-century examples survive at Chester Cathedral (formerly a Benedictine Abbey) and Winchester Cathedral (formerly served by an adjacent Benedictine Priory). When tilted these seats had a small projecting upper ledge upon which a monk could rest his bottom while standing upright during long religious services. Known as misericords (Latin: misericordia, mercy), the consoles of these load-bearing blocks or brackets provided ideal surfaces for carving. From at least the thirteenth century, they were often decorated with floral or religious subjects.

Apart from their regular choir duties, monks of every Order celebrated Mass (a sacred rite which sees the transubstantiation of bread and wine into Christ’s body and blood) at least once a day, and twice on Sundays. There was also a weekly ritual of foot-washing known as Maunday, and special services on Feast days.

Another duty was to say prayers for the souls of the kings and members of the ruling elite whose patronage was the basis of monastic foundations and wealth. Many of these benefactors were buried in the main church and commemorated in heraldic wall paintings and stained-glass windows.

In addition to these daily rituals, the lives of monks were filled with religious ideas and thoughts ranging from the books they read, the sermons they heard, and the works of art they saw at every turn. These works included free-standing statues, architectural carvings such as roof bosses and capitals, decorative tiles, stained-glass windows, vivid wall paintings, carved woodwork and beautifully painted altarpieces. For many, the impact of such imagery intensified their spiritual experiences. Although early Cistercian churches shunned such imagery, their monks had a particular affinity with the Virgin Mary, whose obedience to God had brought Christ into the world. Their churches were dedicated to her and her image appeared on their seals.

Tomb of John I (d. 1216) in the choir of Worcester Cathedral (Benedictine: Worcester), c. 1230.

Fourteenth-century stained-glass panel from a Tree of Jesse scheme, formerly at the Cistercian Abbey of Merevale, now in the parish church of Our Lady, Merevale, (Warwickshire).

Detail of mid-thirteenth-century wall painting depicting St Faith, Horsham St Faith Priory (Benedictine: Norfolk), now a private house.

Tiles depicting Eve with the Apple at Prior Crauden’s chapel, Ely Cathedral Priory (Benedictine: Ely, Cambridgeshire), c. 1324–5.

Painted panel depicting Christ at Binham Abbey (Benedictine: Norfolk), c. 1500, overwritten after the Reformation.

Monks also interacted with pilgrims who visited monasteries seeking cures or help from important miracle-working statues or relics. Such attractions were both prestigious and lucrative, with the gifts of pilgrims often funding ambitious new building programmes. At St Albans Abbey (Benedictine: Hertfordshire) the shrine of the eponymous Roman martyr was guarded by a custos feretri (shrine-keeper) who kept vigil from a raised loft overlooking the tomb. At Canterbury Cathedral stained-glass windows depicted monks recording miracles at the shrine of Thomas Becket, the murdered archbishop, killed in 1170.

The Cure of Mad Matilda from Cologne, early thirteenth-century stained-glass window, Canterbury Cathedral (Benedictine priory: Kent).

Reconstructed shrine of St Alban with fifteenth-century watching loft, St Albans Abbey (Benedictine: now St Albans Cathedral).

Monks also showed important visitors around their abbeys. At Glastonbury (Benedictine: Somerset), manuscript leaves describing the history of the abbey were mounted in a wooden frame and hung on a pillar, much like a modern visitors’ guide. Similar tables or tableaux are known to have been displayed at Hailes Abbey (Cistercian: Gloucestershire), and in other important abbey churches.

According to one Carthusian monk, ‘a monastery without books is like a kitchen without crockery’. Reading was an integral part of a monk’s life and as late as the twelfth century monasteries were the largest storehouses of religious knowledge and ideas. Some had large libraries: in the thirteenth century Rievaulx Abbey had 212 volumes and by 1331 Canterbury Cathedral Priory already owned 1,831 books. Apart from service books and complete Bibles, typical libraries included individual books of the Bible for personal study (such as Judges and Kings from the Old Testament and Matthew and Mark from the New Testament, each with a marginal gloss or commentary written down the side of the page in a smaller script), various works of eminent theologians known as the Church Fathers (patristic books), as well as histories, hagiographies (lives of saints) and a smattering of classical texts.

Carrels in the south walk of Gloucester Abbey cloisters (Benedictine: now Gloucester Cathedral).

In the eleventh century, monks at Canterbury were given a new book to read every year. Spiritual growth through learning and scholarship was central to monastic culture. Monks sat behind one another in the cloister to prevent distractions or whispering and heads were uncovered so that none could pretend to be reading while sleeping. Monks were expected to read aloud, as silent reading was frowned upon.

The cloister alley nearest the church was often reserved for study, and carrels (desks) survive at Worcester Cathedral Priory (Benedictine: Worcestershire) and Gloucester Cathedral (formerly a Benedictine Abbey). Until the late Middle Ages most books were stored in a cupboard in the cloister, rather than in a separate room.

Fourteenth-century book cupboard with elaborately carved tracery screen in the east cloister range at Valle Crucis Abbey (Cistercian: Denbighshire, Wales).

Many Cistercian monasteries marked their books with ownership inscriptions on the flyleaf. Some volumes were inscribed with curses on thieves or careless borrowers. At Reading Abbey (Cluniac: Berkshire) a mid-twelfth-century manuscript was given a fifteenth-century inscription threatening divine punishment against anyone who stole it from the monastery: Liber sancte Marie Radying[ensis] quem qui alienaverit anathema sit. (‘This book belongs to St Mary’s in Reading. A curse on whoever removes it.’)

St Benedict recognised that monks might become bored and jaded over time. To avoid disillusionment and restlessness, he believed that they needed to be kept busy, to vary their days and to occupy their minds with different tasks. While some assumed this meant that monks should help with household chores, by the tenth century wealthy monasteries, such as Cluny, were hiring servants to perform the majority of menial tasks. Peter the Venerable, Abbot from 1122 to 1156, was withering in his dismissal of the idea that educated monks should be ‘begrimed in dirt and bent down with rustic labours’.

Sixteenth-century stained-glass panel, c. 1505–20, depicting Cistercian monks working in the fields, formerly in the cloisters of Altenberg Abbey (Cistercian: Germany) and now in the church of St Mary, Shrewsbury.

Lay brothers’ dormitory in the thirteenth-century Beaulieu Abbey (Cistercian: Hampshire).

Early Cistercian abbeys, on the other hand, expected monks to undertake regular manual labour around their monasteries. This might involve gardening, painting and decorating, and helping at harvest time.

Even so, Cistercian monasteries also relied heavily on servants, especially a special (and segregated) category of lay brothers (conversi) who had their own quarters in the monastery and worshipped separately in the nave of the church. While such lay brothers mainly worked in the monastery precincts as cooks, brewers, beekeepers and porters, or as agricultural labourers in the outlying farms (granges), they also included skilled craftsmen and traders who represented the monastery at markets. At Buildwas Abbey (Cistercian: Shropshire) the monks were outnumbered by lay brothers by two to one; at late-twelfth-century Riveaulx there were about 140 monks and 500 lay brothers.

The twelfth-century interior of Witham Friary, Lower church of Witham Charterhouse (Carthusian: Somerset).

The system of lay brothers was already in decline before the great plague epidemics of the mid-fourteenth century; by the end of the century it had collapsed completely. At Meaux Abbey (Cistercian: Yorkshire) there had been ninety lay brothers in the mid-thirteenth century; after the Black Death (1348) there were none. By the time of the Dissolution, Cistercian monasteries relied entirely on paid servants.

Early Carthusian monasteries consisted of upper and lower sites with the monks living in the former and the lay brethren (frères) who undertook manual work, such as farming or chopping wood, residing in the lower site and worshipping in a separate church.

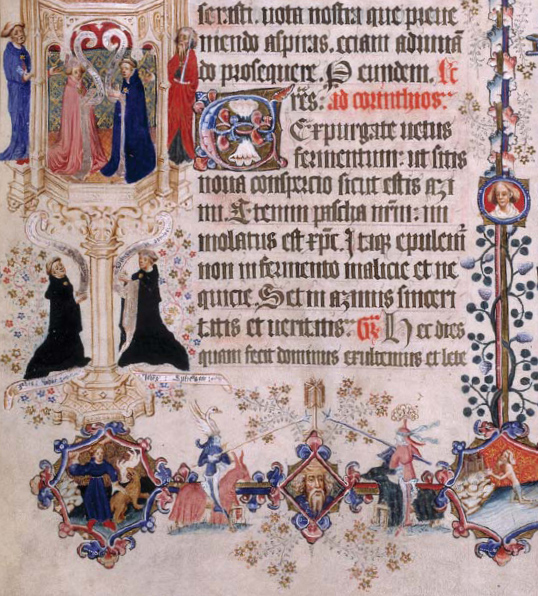

Part of a page for Easter Sunday from The Sherborne Missal with the monks John Whas and John Siferwas kneeling at the base of a column, 1399–1407.

Some monks produced books, working at desks and copying books from an exemplar of the same text. These had to be borrowed or acquired from elsewhere: Cistercian houses probably lent to one another; sometimes monks were sent from one abbey to another to make a copy of a book. Some twelfth-century books at Rochester Cathedral Priory were almost certainly borrowed from nearby Canterbury Cathedral Priory and copied not just word for word, but also in a distinctive ‘prickly’ script.

Between 1167 and 1173 the abbot of St Albans wrote several letters to the Prior of the monastery of St Victor in Paris asking if he could send a copyist to acquire texts written by one of the abbey’s most admired theologians, Hugh of St Victor (c.1096–1141).

From the thirteenth century onwards, however, book production became more professional and many later manuscripts were written and painted by secular artists. An exception includes a beautiful Missal (book for the Mass) written and illustrated 1399–1407 by a monk at Sherborne Abbey (Benedictine: Dorset). It is signed: ‘John Whas, the monk, this book’s transcription undertaking, With early rising found his body aching’.

Interior of the fourteenth-century chapter house at Valle Crucis Abbey (Cistercian: Denbighshire, Wales).

Fragment of a wall painting with a scene from the Book of Revelation, c. 1360–70, Coventry Cathedral Priory chapter house (Benedictine: Coventry, Warwickshire), now in the care of the Priory Visitor Centre, Coventry.

Apart from prayer, study and work, monks were also required to attend daily meetings in the chapter house. This was a large room off the east cloister alley which took its name from the portion or Chapter of the Regula Benedicti which was read from a lectern at the beginning of the proceedings. Such rooms could be highly decorative, with inlaid tiles and wall paintings. At Westminster Abbey (Benedictine: London) and Coventry Cathedral Priory (Benedictine: Warwickshire) the wall paintings depicted scenes from the biblical Book of Revelation, a text that Chapter XII of the Regula Benedicti required monks to learn by heart. During the meeting monks sat on stone benches which ran along the side walls, with the abbot or presiding officer occupying a higher seat in the centre of the east wall. At Westminster Abbey the monks were given mats to sit on. Meetings usually lasted less than an hour; topics included forthcoming services and events, administrative and business decisions including the sealing of documents, remembrance of the dead, and disciplinary matters within the community.

Chapter-house lectern, possibly made for Abbot Adam (1161–89) of Evesham Abbey (Benedictine: Worcestershire), now in the parish church of St Egwin, Norton and Lenchwick (Worcestershire).