Meals were mainly eaten in the refectory, usually a two-storied hall off the cloisters; some of these halls were extremely large. At Worcester Cathedral Priory the refectory still survives as part of an adjoining school. It is 120 feet long and 32 feet wide with an over-sized carving of an enthroned Christ in Majesty on the east wall. At Rievaulx Abbey the ruined hall is 126 feet long and 80 feet high.

At Cleeve Abbey (Cistercian: Somerset) the refectory was remodelled in the fifteenth century and given a timber roof adorned with carved bosses and angels while a wall painting of the Crucifixion (now lost) filled the east wall. At Dover Priory (Benedictine: Kent) a wall painting (also lost) depicting the Last Supper before Christ’s crucifixion provided ‘food for thought’ as the monks ate.

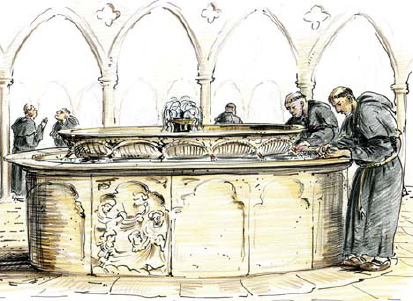

Before entering the frater monks washed their hands in a lavatorium, either a long trough built into the cloister wall (as at Gloucester and Worcester) or a free-standing covered structure in the cloister garth containing a basin set on a circular or polygonal base as at Wenlock Priory(Cluniac: Shropshire). In both cases the lavers were supplied with piped water and drains. Such lavers could be lavishly decorated. At Gloucester Abbey the ceiling of the laver was enriched with fan vaulting; at Wenlock Priory the base of the trough included carved panels, one of which showed Christ calling the Apostles on the Sea of Galilee. Fresh towels were stored in nearby cupboards.

Spoons and napkins were collected as the monks entered the refectory. There was a raised dais or platform at the end furthest from the entrance where the abbot and his senior officers presided and benches along the side walls where the monks sat, facing inwards.

Benches and tables could be free-standing or set on stone legs. At Bardney Abbey (Benedictine: Lincolnshire) the wooden table tops were about 20 feet long and rested on Y-shaped stone supports carved with the heads of a monk, abbot and king on the visible side. The wall benches had similar supports.

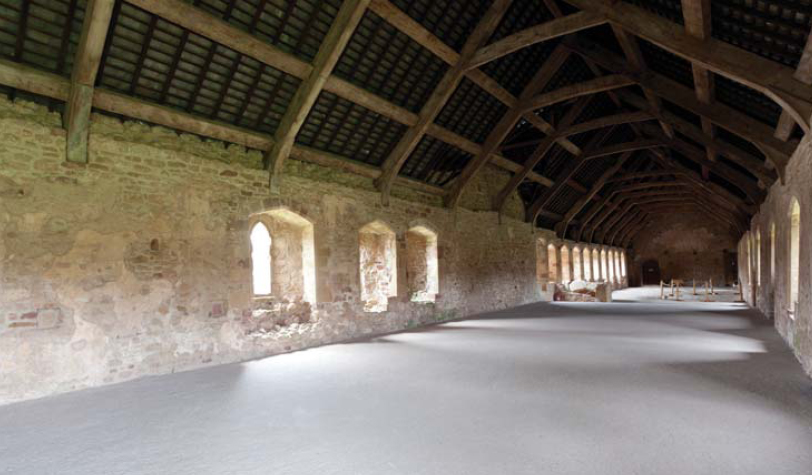

The stairs leading to Cleeve Abbey refectory (Cistercian: Somerset), which dates from the fifteenth century.

Fan-vaulted laver in north cloister wall, fifteenth-century, Gloucester Abbey (Benedictine: now Gloucester Cathedral).

Artist’s impression of Cleeve Abbey refectory.

Every meal began with Grace, a prayer of thanks. During the meal a senior monk read aloud from a pulpit-style lectern built into the wall or a window splay. Good examples survive in the parish church at Beaulieu (see page 44), formerly the refectory of Beaulieu Abbey (Cistercian: Hampshire), and at Chester Cathedral (formerly a Benedictine abbey). Anybody who spilt his drink or otherwise interrupted the reader had to stand up and lie prostrate on the floor until told to return to his place. At Sawley Abbey (Cistercian: Lancashire) novices who finished their meals before others were advised to occupy their time by arranging the bread-crumbs on the tablecloth into the form of a cross.

Christ calling Peter and Andrew on the Sea of Galilee, thirteenth-century laver panel at Wenlock Priory (Cluniac: Shropshire).

In the early Middle Ages a typical meal lasted about half an hour and was served once a day in the winter and twice in the summer when days were longer. Monks were expected to eat quietly and cleanly. Wiping hands, mouths and knives on tablecloths was prohibited. Talking was forbidden although sign language (see page 53) was permitted. Benedictines usually ate better than the early Cistercians, who regarded food as a necessity rather than a pleasurable treat. Some monks fasted excessively and ate very little. In the early twelfth century a typical monastic diet consisted of cereals or cooked vegetables (pulmenta), enriched with small portions of protein such as egg, cheese or fish. Home-grown fruit might also be offered. It seems that sometimes the cuisine was stomach-churning – a twelfth-century monk at Rievaulx Abbey complained that the food was ‘more bitter than wormwood’ – but in general, portions were adequate as under-nourishment would have been pointless. In addition to the basic dishes, each monk also received a daily allowance of bread and a measure of ale. On special occasions, such as saints’ days or the anniversary of the monastery’s foundation, this diet was augmented by additional or better-quality dishes, known as ‘pittances’.

Artist’s impression of the Wenlock Priory laver.

Flavouring was limited to salt or vinegars in case richly flavoured foods induced sluggishness and distracted monks from prayer and work.

Although red meat was never served in the refectory, monks were not vegetarians in the modern sense. The origins of the ban lay in fears that eating meat would arouse sexual and other physical desires and temptations. As a result meat was initially only served in the infirmary where it was thought to assist a patient’s recovery, but these rules were gradually relaxed during the later Middle Ages. From the late twelfth century onwards Benedictine and Cluniac monks were eating meat in a special chamber, known as a misericord (‘mercy’) with Cistercians following suit in the early fourteenth century. Once again the Carthusians were different, refusing to eat meat under any circumstances, including serving it to the sick, in case its pleasures tempted monks to feign illnesses!

Lectern in the former refectory of Beaulieu Abbey, now Beaulieu Abbey Church (Cistercian: Hampshire).

Diets were much richer in wealthy sixteenth-century monasteries.

In line with rising prosperity and changes in monastic practices, by the late Middle Ages the diets of most monks had improved dramatically. Even allowing for the fact that wealthy monasteries often entertained important guests, a single week’s kitchen bill at Dover Priory in 1530 reads like a feast. It included payments for mutton, lamb, geese and capons, oysters, salt salmon, fresh fish, butter and eggs.

Based on the early sixteenth-century account rolls at Westminster Abbey it has been estimated that each monk consumed an average of two pounds of meat or fish each day, one gallon of ale, and a loaf of bread weighing two and a half pounds. Stews and cheese flans were popular while only small amounts of fruit and vegetables were eaten. Some Cistercian abbeys were little different: in 1520 two thirds of Whalley Abbey’s (Lancashire) income – £640 out of a total of £895 – was spent on food and drink, including dates, figs and sugar. Studies of skeletons recovered from the cemeteries of Stratford Langthorne Abbey (Cistercian: London) and Bermondsey Abbey (Cluniac: London) show evidence of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), a condition associated with a calorie-rich diet and obesity (with attendant late-onset diabetes).

With the exception of Carthusians, who lived alone in their individual cells, most monks slept communally in a long, unheated first-floor dormitory. The beds had straw mattresses and were ranged along the walls with storage cupboards and chests lining the centre of the room. Towards the end of the Middle Ages many monasteries fitted partitions between the beds to give monks a greater degree of privacy. Apart from the entrance from the cloister (‘day stairs’) some dormitories also included stairs leading directly into the church for night-time services; these were known as the ‘night stairs’.

The night stairs, Hexham Abbey (Augustinian: Northumberland).

Fifteenth-century oak chest at Pershore Abbey (Benedictine: Worcestershire).

Sleep proved difficult for many as they were woken up during the middle of the night by bells or roused by others to proceed to the church to sing the Night Office. Lateness was a disciplinary offence, as was falling asleep during services; senior monks would shine lights in the faces of any monks who seemed drowsy.

A combination of interrupted sleep, together with other disturbances, such as the unsettling sounds of snoring and the cries of monks suffering nightmares or ecstatic visions, caused various sleeping disorders, including insomnia. When monks at Sawley Abbey complained of difficulties in getting to sleep they were told to imagine their beds were their graves; at Forde Abbey (Cistercian: Dorset) monks prayed over the bed of an insomniac until he was cured.

Dormitories were also patrolled by senior monks to monitor behaviour and to ensure that candles were extinguished. Talking was forbidden. As monks slept in their habits, other rules stipulated that even in the heat of summer only their heads, feet and arms could be exposed in case demons were drawn to their bare flesh.

The fifteenth-century dormitory at Cleeve Abbey (Cistercian: Somerset).

In early monasteries abbots slept in the same dormitory as other monks but as institutions become more prosperous many lived in luxurious lodgings either in the claustral range or in separate houses. At Fountains Abbey the infirmary hall was remodelled in the fifteenth century to create self-contained two-storey apartments for senior monks.

The dormitory also included an entrance to the first-floor latrine block. Cubicles were separated by screens. At Lewes Priory (Cluniac: East Sussex) there were at least fifty-nine cubicles for a population of about one hundred monks. There was also an enclosed room which may have been used as a bathhouse.

Artist’s impression of latrines.

The Abbot’s parlour at fifteenth-century Muchelney Abbey (Benedictine: Somerset).

As the workings of the ‘lower body’, particularly excrement (material corruption) were often seen as the embodiment of sin, latrines were feared as the haunt of demons that wallowed in the filth and stink of the dropslots. According to a history of St Albans Abbey written about 1390, an untrustworthy twelfth-century monk named William Pygun died in the latrines after the other monks heard a voice rising from the dungpit urging Satan to seize him.

Because of restrictions on the times and conditions for visiting the latrines monks made use of portable urinals known as ‘jordans’ whose contents were subsequently used for bleaching cloth or tanning animal skins. Drains often flushed into ditches, rivers, soakaways, and sometimes even fishponds where the excreta nourished the plankton on which the fish fed. At Muchelney Abbey (Benedictine: Somerset) the latrine block retains a series of arches at ground-floor level, which were the outflow to a sewer.

As noted earlier, monks had a relatively high standard of living compared to the general population, with diets and sanitation better than average. In the fifteenth century, applicants to the Benedictine Order were screened and asked if they had any contagious diseases. Infirmary accounts seldom name specific ailments, but in the sixteenth century some monks at Westminster Abbey were listed as suffering from a complaint known as ‘morbus in tibia’, a disease of the shinbone – possibly leg ulcers caused by a lack of vitamin C in their diet. Excavations on the infirmary site at Beaulieu Abbey unearthed a number of skeletons of men aged over sixty who were crippled by chronic rheumatism.

Monks were bled up to nine times a year.

Contemporary medical opinion believed that regular bloodletting, otherwise known as ‘seyney’ (from the French seigné: ‘bled’), was an important contribution to maintaining good health and repressing sexual temptation. Some monks were bled nine times a year, usually in the warming room or the infirmary, a separate complex lying outside the cloister enclosure equipped with its own chapel, cloister, refectory, dorter, latrine and kitchens. This block also often accommodated elderly and infirm members of the community.

Such bloodletting sessions may have been enjoyed by some monks, as meat was served afterwards to assist their recovery. As part of the same ‘treat’ they were often allowed to stay overnight in the warmer and quieter confines of the infirmary or convalesce at a country property.

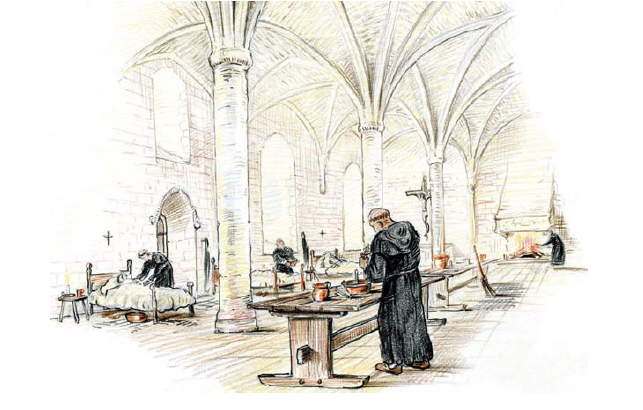

Infirmaries could be large with lofty roofs and a fireplace at one end of the hall or ward. At Ely Cathedral Priory (Benedictine: Cambridgeshire) the infirmary was a 192-foot-long rectangular building with side aisles. After the Dissolution the side-aisle arches were blocked up and the roofless central floor space converted to a road now known as Firmary Lane. Infirmaries elsewhere were almost as large: at Fountains Abbey the infirmary hall measured 180 feet by 78 feet; at Furness Abbey (Cistercian: Cumbria) it stretched to 125 feet by 50 feet.

Firmary Lane, Ely Cathedral Priory (Benedictine: Cambridgeshire).

An artist’s impression of the infirmary.

Infirmaries were manned by specially trained staff. Physicians, surgeons and apothecaries were usually hired as required, although among the letters of the future Edward II is a request to the Abbot of Reading Abbey in 1302–3 asking if the monks could care for one of his friends who had wounded his hand, as he understood they ‘had a good surgeon at the house’.

At Norwich Cathedral Priory (Benedictine: Norfolk) the infirmary had its own garden where herbs and medicinal plants were grown, such as rhubarb, peonies (the roots, flowers, and seeds were all used in the medieval pharmacy), fennel, and squills. Infusions of catmint, parsley, lovage, celery, pennyroyal, wild thyme and fennel were used to combat colds. Surviving accounts of this wealthy monastery show that liquorice, aniseed, and dragon’s blood (a resin from certain trees and shrubs that was used to treat diarrhoea, dysentery diseases and other illnesses), were among the more exotic drugs and spices purchased for the benefit of the monks. Gifts of medicine to the poor are also recorded.

Some signs were based on miming actions. The Ely sign book includes:

• For a book, extend the hand and move it as the page of a book is usually turned

• For bread, make a circle with both thumbs and the next two fingers

• For a ration of wine, turn the hollowed hand downwards

• For honey, put out the tongue and touch it with fingers as if you wish to lick

• For a knife, draw the hand across the middle of the palm

• For sleep, place hands on cheek as when sleeping

• For silence, place a finger on closed mouth

• For saying ‘no’, place the tip of the middle finger under the thumb and make it spring back as with a flick

• For something good, place the thumb on one cheek and other fingers on the other and draw gently downwards onto the chin.

The sign for bread

The sign for a ration of wine

The sign for honey

The sign for a knife

The sign for silence

The sign for sleep

Although monasteries were intended to be oases of contemplation and peace, their calmness was frequently jarred by the pattering of servants, builders and visitors. Monks themselves, however, were prohibited from talking during church services, in the dormitory at night, and during mealtimes in the refectory. Where conversations were permitted in the cloisters or parlours, they were expected to be brief and businesslike. Gossiping was frowned upon as frivolous and potentially dangerous, either because it could foment tensions and jealousies within the community or because it could lead to dissent and disobedience to the abbot and the senior office holders.

During the ninth century the monks at Cluny Abbey developed a sophisticated sign language to circumvent these prohibitions, which was subsequently written down and learned by novice monks. The earliest written Anglo-Saxon sign list to survive in England – the Monasteriales Indiciae, contaning 127 signs – was probably compiled in the late tenth century and copied into a manuscript used by monks at Canterbury Cathedral Priory in the mid-eleventh century. Two fourteenth-century lists from Bury St Edmunds Abbey contain 141 and 198 signs respectively. Around 1500 the monks at Ely Cathedral Priory used a list of 109 signs.

Most sign lists consisted of simple nouns, adjectives and a few verbs. They include signs relevant to church services, eating and drinking in the refectory, and discussing everyday activities in the cloister. In some eyes even this was too many. When the Welsh historian, Gerald of Wales (1146–c.1223), ate at Canterbury Cathedral Priory in 1180 he complained, ‘There were the monks … all of them gesticulating with fingers, hands and arms and whistling to one another instead of speaking … so that I seemed to be seated at a stage play or among actors and jesters.’

Board game, north cloister walk, Gloucester Abbey(Benedictine: now Gloucester Cathedral).

Although primarily ‘houses of prayer’ and reverence, monks also laughed and played. They were neither unworldly nor meek; sobriety was interspersed with moments of warmth ... and occasional profanity. Despite the disapproval of senior church figures, for much of the Middle Ages Benedictine monasteries often elected a ‘boy abbot’ in December, signalling several days of feasting and play with novices changing places with the superior of the house. Entertainers were also hired by wealthy houses: at Durham Cathedral Priory the accounts book includes numerous entries for the costs of musicians and players, including twelve minstrels at the Feast of Saint Cuthbert in 1375–6. At Boxgrove (Benedictine: Sussex) the prior was admonished in 1518 for entering into archery matches with lay people, while at Chester Abbey the monks were chided by a visiting Bishop in 1315 and 1323 for feeding the leftovers from the refectory to their greyhounds rather than giving them to the poor. Dice, cards, and games such as ‘Nine Men’s Morris’ and ‘Fox and Geese’ were also played; a stone bench in the cloisters of Gloucester Cathedral retains a scratched board for playing the latter game. Allegations of late-night drinking sessions blighted some monasteries. When the diarist Margery Kempe (1378–c.1438) visited Hailes Abbey in 1417, she was shocked by monks who swore crude oaths in her presence. On a lighter note, in the sixteenth century, monks from Durham took it in turns to enjoy short ‘holidays’ at Finchale priory (Benedictine: Co. Durham), four miles north of the city. Even the Carthusians relaxed with a weekly socialising walk, the spatiamentum. In every sense monks remained very human.

The incised grave-slab of William Alford (d. 1490), Abbot of Bordesley Abbey (Cistercian: Worcestershire) now stands in the parish church of St Peter, Hinton on the Green (Worcestershire).

In most monasteries death was an elaborate ritual. At Syon Abbey (Bridgettine: Middlesex), a fashionable nunnery on the western outskirts of London, an open grave was maintained near the entrance to the church to remind worshippers that death was inevitable and judgement certain. At Canterbury Cathedral Priory when a monk was close to death the entire community gathered in the church and processed to the infirmary where the dying man was sprinkled with holy water (‘asperged’) and made a public confession of his sins. Cistercians deputed rotas of monks to sit with their dying colleagues.

The grave of Abbot Roger II (1252–72) was excavated in 1918 from the south transept of St Augustine’s Abbey church (Benedictine: Canterbury, Kent). Note the stone pillow beneath his head.

After death, Benedictine and Cistercian monks were laid out on the ground on a sackcloth which had been placed on a cross-shaped scatter of ashes. Their bodies were thereafter washed, wrapped in a shroud and buried without a coffin in the monastic cemetery. Carthusian monks were buried in the cloister garth.

Cluniacs were laid on a hair shirt and hooded habit, with their hands arranged as if in prayer. Abbots were often buried in chapter houses together with their regalia of office, such as their rings and crozier (a staff with a head shaped like a shepherd’s crook). At Bury St Edmunds Abbey two abbots were laid before an image of the Virgin Mary at the north entrance to the choir. At St Augustine’s Abbey at Canterbury, Abbot Roger II (d. 1272) was interred in a coffin with a stone pillow for his head.

In many monasteries gifts were made to the poor in memory of the dead monk. At Evesham Abbey (Benedictine: Worcestershire) this included a ‘seam’ of corn (a seam was worth eight bushels, one bushel being equivalent to eight gallons).