THE SUPPRESSION OF MONASTICISM would have seemed inconceivable at the beginning of the sixteenth century. Although the number of monks had shrunk since the high peaks of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, most of the larger abbeys were financially stable, books were being bought and major building programmes were still being commissioned. The Carthusian priory at Mount Grace (Yorkshire) even had a waiting list of people wanting to join. But when the end came it was sudden and unstoppable.

The indirect cause of the destruction was the Pope’s refusal to grant Henry VIII a divorce from Catherine of Aragon (1485–1536), which he needed in order to marry Anne Boleyn (1501–36). Determined to press ahead without papal approval, the king declared himself Supreme Head of the English Church in 1534 and aligned himself with the Protestant Reformation, triggering a succession of ever more extreme measures against the authority and beliefs of the traditional Catholic Church.

In 1535 Henry commissioned a survey of the wealth of ‘his’ church – the Valor Ecclesiasticus (‘church valuation’) – the first time that the net wealth of the monasteries had been assessed.

In 1536 parliament approved the suppression of two hundred of the smaller and poorer houses, including Waverley which had an income of £174 and Tintern with its income of £192. More closures followed when monks in some northern monasteries joined an uprising in 1537 known as ‘the Pilgrimage of Grace’ protesting against government policies. The abbots of Whalley and Jervaulx (Cistercian: Yorkshire), were executed as a warning to others who aided rebellion.

Over the next few years the king’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell (c. 1485–1540), employed a range of tactics to persuade the remaining abbots to ‘voluntarily’ surrender their properties to the crown. These ranged from terror and the discrediting of monastic reputations, to pay-offs and generous pensions for those who co-operated and went quietly. None of this would have been as easy if monasticism had enjoyed deep-rooted public support, but this had been gradually evaporating over the preceding centuries as fewer people became monks, benefactors endowed other institutions (including their own churches), and individualism became more assertive. Jealousy over their wealth and Protestant hostility to miracle-working shrines added to their isolation.

Thomas Cromwell (c. 1485–1540), after a painting by Hans Holbein.

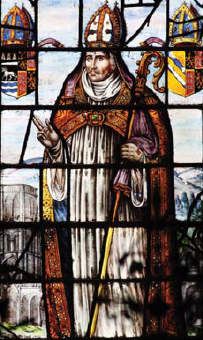

Some abbots and monks made the best of their new circumstances and changed sides – a few more than once. When Osney (Oseney) Abbey (Augustinian: Oxford) was dissolved in 1539 the last abbot, Robert King (d. 1558), a former Cistercian monk, became the bishop of a new – and very short-lived – Protestant diocese known as Thame and Oseney with the abbey converted to a Cathedral. Three years later following another reorganisation he became the first Bishop of Oxford after a different former Augustinian priory in the city was raised to Cathedral status in 1545 and Oseney Abbey demoted. Ten years later, however, he reverted to Catholicism and served as one of the judges who sentenced Archbishop Thomas Cranmer (1489–1556), a leading figure in the English Reformation, to death. A window in Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford, painted around 1630–40, shows Bishop King standing beside an image of the now lost abbey of Oseney.

Oxford was not the only new Cathedral diocese centred around a former abbey church: Chester and Gloucester also survived for the same reason. Most buildings, however, were not so lucky and were sold for salvage with their roofs stripped and their walls quarried for stone. At Quarr Abbey (Cistercian: Isle of Wight), for example, the stone was used to build coastal forts at Cowes. Monastic graves were also robbed, as at Rievaulx, where tombs in the chapter house appear to have been dug up and the bones scattered. In other instances, parts of the buildings survived when a local town bought the church for parish use (at Malmesbury, Pershore (Benedictine: Worcestershire), Sherborne and Tewkesbury, for example), or when they were restored by individuals (Dore Abbey – Cistercian: Herefordshire) or converted into country estates for wealthy Tudors, as at Forde Abbey and Lacock Abbey (Augustinian nunnery: Wiltshire). As a result some have survived as lively centres of enduring Christian worship.

Bishop Robert King with Oseney Abbey shown at the lower left side of the window, Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford, 1630–40.

But perhaps it is as ruins that most medieval monasteries are remembered today; evocative monuments of a way of life which continues to intrigue present-day visitors as much as it did four hundred years ago when the playwright, John Webster (c. 1580–c. 1634) wrote:

I do love these ancient ruins.

We never tread upon them, but we set

Our foot upon some reverend history.

The nave of Malmesbury Abbey (Benedictine: Wiltshire).